The History of Business Analysis

Power Users and Technicians

I first joined the ranks of business analysts in 1999. I was a power user of the software solutions that were being developed. An opening came up for a “product manager” role on the team, and I jumped on the opportunity to join the project team. I was hired, but not for my ability to do business analysis or even lead product development. I was hired because I knew the business and could envision how technology could make the job of state budget development easier. Simply put, I was a great power user. I didn’t know what use cases, data models, wire frames, insert tool here … were. I didn’t know how to analyze alternatives to my thoughts, elicit ideas from those who may have better ideas than myself, or how to effectively communicate with technicians and customers. Some of these came to me naturally, some I learned through experience and osmosis, and some I learned later when formal training opportunities arose.

Was this a problem? Yes. I will share two examples of where my lack of understanding of business analysis cost the projects I worked on time and money.

The Pareto Example

We had one customer that was larger and more complex than all the rest. Being “special”, they had more interesting requirements for features than most of our user base. Being the problem solver that I am, I listened carefully to the representative’s feature request and was determined to figure out how to meet the need. The answer came to me at 2:00 a.m. I would spend the next couple of days refining the concept and developing a prototype that I could present to the customer and the project team. The result would be a change to the project to accommodate the special requirements that added substantial scope and risk without corresponding time and money. We did get the feature into a second release, and that customer was happy.

The Problem

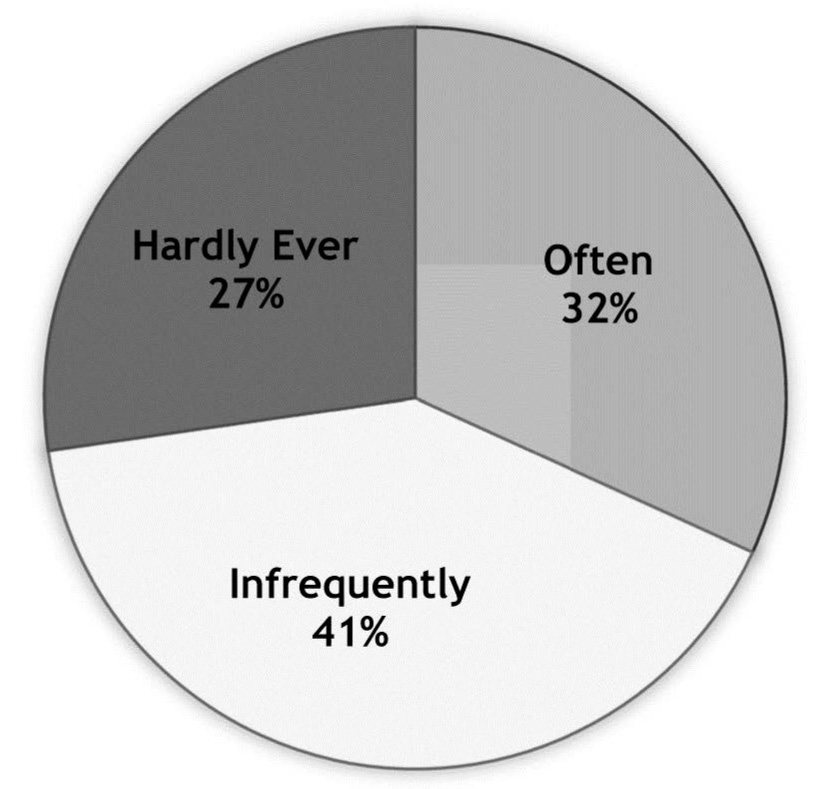

A few years later, I went to a presentation where the presenter discussed a pie chart that depicted how much of software features are used and at what frequency. I now use this pie chart often in my own presentations on bringing value to the business with the project we do.

This perfectly highlights the problem with the solution I had identified. The complex feature that I had conceptualized to solve a requirement of a single customer fell into the 27 percent Hardly Ever used in the first couple of years for use. In fact, it was never used once that organization’s representative left.

Figure 3 Percentage of Features and Functions Used Source: Modernization in Place, Standish Group, 201511

By the third project with this program team, I had the brilliant idea that we could streamline the time needed to design the system by doing it myself! Now, being a power user means that my definition of design is what we now call user experience (UX) design, limited to designing the user interface. I proceeded to write a 150-page “design document” for our next solution. I developed “mock screens” (aka wireframes) using Access forms and built out every screen of the solution, documenting every data field and its attributes. It was the ultimate requirements document! I just knew the developers would love me and my document and we’d knock out the solution in half the time expected. I was wrong.

Design document review was a nightmare. Everybody hated it and tore it apart. In hindsight, I have to say rightfully so. Who was I to develop the UX design for an entire system, and not a small one, in a vacuum? I didn’t even elicit requirements from users. Why? I knew what the system needed to do.

The Problem

The problem was that I presumed that my way was the best way, the only right way. I had no concept of what it would take to implement my design. My worse offense was not valuing the experience and input of the customer and team members. My design was not the only way. My design was not the best way. Many of my “requirements” didn’t make sense to implement given the technology tools, infrastructure, and standards the developers used. The time spent reviewing and updating my “design document” would have been much better spent in eliciting, documenting, communicating, and managing functional requirements.

I saw others that came into the organization from the user community make the same mistakes. So repeat after me: “A power user is not a business analyst.” In reality, they are probably just a know-it-all. I was.

Common Business Analysis Mistakes

Which of the following common business analysis mistakes have you experienced from your business analyst, or even done yourself?

1. Hand over a 200-page requirements document for stakeholder approval.

2. Accept additional scope to the project without determining the cost-benefit and getting sponsor approval.

3. Document design preferences as business requirements.

4. Miss a stakeholder group and, consequently, a big requirement.

5. Assume design and test will meet requirements as intended without reviewing technical team documentation.

6. Create an unorganized laundry list of “requirements”.

Don’t let these bad experiences happen in your project. Use trained, experienced business analysts that understand how to talk to the business users about what is truly needed and will bring value from the project, can translate this for the technologist, and have the influencing skills to help guide project decisions.

Business Analysis Gone Right!

5 Why’s

Years later I was managing a project and became engaged in a discussion between the project’s business analyst and customer. The customer asked for a data field. This field had already been ruled out as of out of scope. This was the same special and complex customer I mentioned in the first story. The business analyst (BA) responded “okay” and started writing this down as a new requirement. You should have seen the look on the lead developer’s face!!! Now more experienced and wiser, I stepped in.

Me: Why do you need this field?

Customer: Because it is how we know how to distribute workload

Me: What is the basis of distributing workload?

Customer: Division within the organization

Me: So, you don’t need this field per se, you need a way to distribute workload based on division?

Customer: Yes

Me: And that can be done with combination of the other fields we have determined are in scope?

Customer: Yes

I now saved the project team from revisiting old decisions and redesigning the database and user interface by digging a bit further to understand the real need. That is what a trained, experienced business analyst brings to the table.

IIBA and Professional Recognition

More than 10 years ago, a group of business analysis professionals in Toronto, Canada, recognized the need for and value of a professional organization dedicated to the profession of Business Analysis. IIBA12 was formed in 2003 and officially became a professional organization in 2004. The vision of IIBA is “to be the leading worldwide professional association for business analysts” with the mission to “develop and maintain standards for the practice of business analysis and for the certification of its practitioners.” This means that those who do business analysis now have published best practices with the Guide to the Business Analysis Body of Knowledge (BABOK® Guide, Version 3.0) for reference, and certification13 is available to demonstrate expertise. The Body of Knowledge and certification are comparable to those of other professional organizations, and, in fact, modeled very closely to the Project Management Institute (PMI),14 their counterpart for the profession of project management. While IIBA is in its infancy, the growth has been astronomical, providing an indication of the need and acceptance. As of February 2015, IIBA now has more than 28,000 members in 109 countries on the six continents.

We find, when diving into the BABOK® Guide, Version 3.0, that IIBA has provided a broad definition of “business analysis”. The BABOK® Guide provides best practices in six “knowledge areas”: Business Analysis Planning and Monitoring, Elicitation, Requirements Life Cycle Management, Strategy Analysis, Requirements Analysis and Design Definition, and Solution Evaluation. The BABOK® Guide v. 3 serves as the foundation for the best practices with tasks, tools, and techniques by knowledge area. It serves as the foundation for the business analysis best practices described through the remainder of this book.

State of Business Analysis Today

While IIBA has achieved growth both geographically and throughout the business analysis community, there is still a large gap of knowledge across the project industry. When I presented at the PMI North American Global Congress 2013 in New Orleans, Louisiana, I asked a group of about 50 project managers, “Who has heard of IIBA?” Only a handful of the participants raised their hands. This shows how far IIBA has to go to be widely recognized. Both professions are in the business of projects. The project industry would best be served if the organizations worked in concert with each other to provide the best overall professional guidance to our shared constituents.

When I took the Presidency of the Seattle IIBA Chapter in 2012, I did so with a vision and goal to be able to walk into any gathering of professionals and introduce myself as the President of the Seattle IIBA Chapter, and more people would know what IIBA is than not. I am still working on that!

One major challenge to the profession of business analysis is a lack of acceptance of the profession. While it is true that many roles include business analysis activities, having a dedicated business analysis professional will provide a greater chance of a project that adds value to the organization. Instead, too often, the organization burdens the project manager or business representative with this analysis work. The person tasked with this work may or may not be skilled in business analysis. They will not have capacity and focus to provide the role justice. This is discussed in greater detail in the Introduction.

PMI is now directly addressing the need for professional business analysis, and this will help raise awareness of the role of the business analyst in successful project completion with solutions that bring value to the business. There is much conversation and controversy in the business analysis world about PMI having taken this step to enter the business analysis space in direct competition with IIBA. While I do believe that IIBA provides superior guidance on business analysis, especially as it relates to organization or strategic analysis, the voice and the reach of the PMI cannot be ignored. Overall, PMI’s entry into business analysis will be good for the profession.

Why did they do it? From all accounts, the PMI had approached IIBA to partner it; however, IIBA did not feel that their goals were in alignment and so declined the opportunity. The result is now two bodies supporting business analysis and providing professional certification. They say a little competition is healthy. Let’s hope so. At the very least, it demonstrates the importance of mature, skilled business analysis in our projects across all industries.

A listing of organizations and certifications in business analysis has been provided.

Business Analysis Organizations & Certifications

International Institute of Business Analysis (est. 2004)

• Certified Business Analysis Professional™ (CBAP®)

• Certification of Competency in Business Analysis™ (CCBA®)

Project Management Institute (est. 1969)

• PMI Professional in Business Analysis (PMI-PBAMSM)

British Computing Society (est. 1957)

• BCS International Diploma in Business Analysis

• Expert BA Award

Vision for Tomorrow

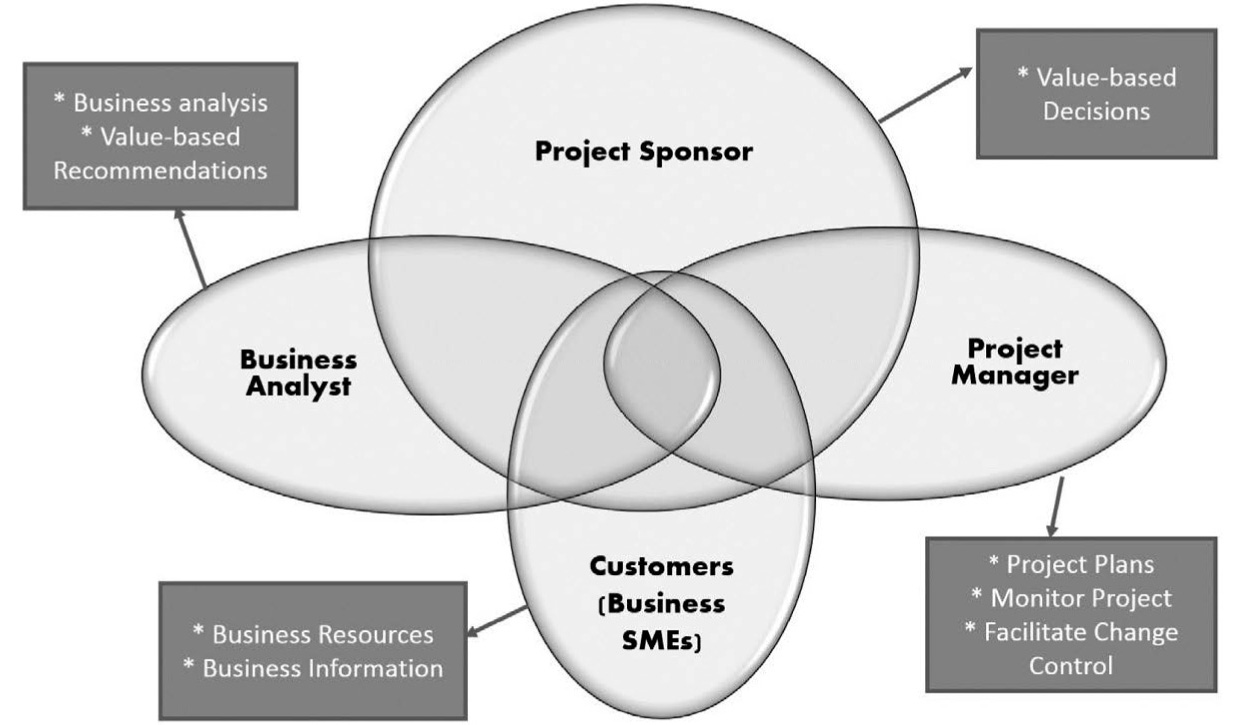

As organizations and industries mature their use of the business analyst profession, we will have projects that have a skilled business analyst on the project leadership team alongside the project manager, project sponsors, and customer (or business owner).

Figure 4 shows the makeup of the ideal project leadership team (or Project Power Team) that will have the greatest input to deliver projects that bring value to the business, the true definition of project success. A project that delivers designated scope within the approved schedule and budget does not guarantee success in and of itself. These roles work together to ensure that the project delivers value to the organization. (More on this in Chapter 13—Standardizing roles and processes.)

Projects will be judged on the value the implementation brought to the organization in the long run rather than the investment cost and schedule. It will become common place to analyze solutions that are not technology driven as alternatives to our go-to “throw-IT-at-it” mentality.

Organizations will invest in business analysis with recruitment, training, and support in organizations such as IIBA and PMI, and they will see a better return on investment of their projects as a result. This will be covered in greater detail in Chapter 13—Standardizing roles and processes.

Sounds like a good world to me. Are you in?

11Source: 2015, Modernization in Place, Standish Group.

12International Institute of Business Analysis (IIBA) founded in 2003. www.iiba.org.

13Certified Business Analysis Profession™ (CBAP©) and Certification of Competency in Business Analysis™ (CCBA®).

14Project Management Institute (PMI)® founded in 1969. www.pmi.org.

15Originally published in James, V., Rosenhead, R., and Taylor, P. (2013). Strategies for Project Sponsorship. Virginia, VA: Management Concepts Press.