This chapter looks at the complexity of what can be called modern regulatory capitalism, and suggests that the focus on rules is counterproductive. It suggests that the idea of responsive regulation is likely to be more effective regulation in that it takes greater notice of the ethical nature of the issues it attempts to address, and will be more likely to garner positive responses.

Regulation touches the financial industry at many points. Australia, for instance, has separate agencies for prudential regulation, market conduct, competition, money laundering, human and consumer rights plus a range of public and private sector tribunals and other dispute resolution bodies. These agencies are in turn subject to international regulatory bodies such as the Bank of International Settlements (the Basel Rules), the International Accounting Standards Board, and a host of institutions that come under the United Nations and the G20 governments. David Levi-Faur and Jacint Jordana coined the term regulatory capitalism to describe the current international order.

Democratic governance is no longer about the delegation of authority to elected representative but a form of second-level indirect representative democracy—citizens elect representatives who control and supervise ‘experts’ who formulate and administer policies in an autonomous fashion from their regulatory bastions …

Thus, it is argued that a new division of labor between state and society (e.g., privatization) is accompanied by an increase in delegation, proliferation of new technologies of regulation, formalization of inter-institutional and intra-institutional relations, and the proliferation of mechanisms of self-regulation in the shadow of the state. Regulation, though not necessarily in the old-fashioned mode of command and control and not directly exercised by the state, seems to be the wave of the future, and the current wave of regulatory reforms constitutes a new chapter in the history of regulation (2005, 13).

John Braithwaite (2008) has developed the ideas in more detail, including ideas as to what to do to improve regulatory capitalism. His view is that much of the regulation represents a pleasing dispersion of mutually accountable power, including the view that multi-national corporations can effectively help regulate states—as they did in a small way in Apartheid South Africa. He suggests that the large companies, like large governments, have provided the investment and concentration of resources that has led much of the technological development of the last century, although he recognizes the downside:

But other forms of regulation also prove impossible for small business to satisfy. In many industry sectors, regulation drives small firms that cannot meet regulatory demands into bankruptcy, enabling large corporates to take over their customers … For this reason, large corporations often use their political clout to lobby for regulations they know they will easily satisfy but that small competitors will not be able to manage. They also lobby for ratcheting up regulation that benefits them directly (e.g. longer patent monopolies) but that are mainly a cost for small business (2005a, 25).

He does not mention the role of the large professional consulting firms, but they have a considerable interest in complex regulation. One solution Braithwaite supports is for large companies to be required to monitor and publicly report on their interaction with all stakeholders to identify where they—perhaps inadvertently—cause harm. The widely supported International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) has taken up the challenge of reporting the value that they create and consume in not only financial, but also social and environmental terms.1 Integrity aspires to more clarity and transparency.

Another Braithwaite suggestion is meta-regulation, which he defines as follows:

Meta-regulation means the regulation by one actor of a process whereby another engages in regulation. An example is the government regulating a process of corporate self-regulation—i.e. regulated self-regulation (2005b, iv).

He illustrates by the following suggestions as to personal responses:

Those of us in jobs can start in the organizations where we work; children and those with children can start in their schools. One of the pragmatic appeals of the strategy is that the first mover to improve any particular kind of access to justice can be a private organization that uses the improvement as a competitive tool or as moral leadership, a state organization that requires it as a matter of regulation, or an NGO that demands it as a matter of politics from below. Meta regulatory strategy is about ratcheting-up incrementally. The meta regulatory institutional design is to push NGO, state and corporate ratchets in series—so when one justice ratchet moves up a click there are knock-on effects on the other ratchets (2005b, 43).

Concern over the negative effects on small business needs also to be matched with concern over the Washington Consensus that has used international organizations to impose the interests of western nations and transnational corporations on poorer countries. These countries also need meta-regulatory support.

Complexity

The ongoing flood of new regulation is an increasing challenge. UK academic John Kay describes it2:

… regulation that is at once extensive and intrusive, yet ineffective and largely captured by financial sector interests. Such capture is sometimes crudely corrupt, as in the US where politics is in thrall to Wall Street money. The European position is better described as intellectual capture. Regulators come to see the industry through the eyes of market participants rather than the end users they exist to serve, because market participants are the only source of the detailed information and expertise this type of regulation requires. This complexity has created a financial regulation industry—an army of compliance officers, regulators, consultants and advisers—with a vested interest in the regulation industry’s expansion.

Regulatory overload is not easy to oppose. Each new regulation has some advantage that, in isolation, can be justified, particularly if it appears more sophisticated. By opposing it, you may seem reckless or not up to the new sophistication. Andrew Haldane, an Executive Director of the Bank of England, and Vasileios Madouros, have therefore done us a great service in showing that the complex regulatory models introduced in the last two decades do not work well. In particular, Basel I rules would have worked better than Basel II in the 2008 financial crash. Complex regulations are often difficult to understand, but it is almost impossible to keep all the details in mind. They can also crowd out deep understanding and undervalue the virtues of wisdom, justice, and courage.

The operational risk capital required by Basel’s Advanced Measurement Approaches provides an egregious example. It requires a huge effort in collecting and analyzing data, but the impact has been to increase capital by some 10 percent, which is barely material. Operational risks are dependent on what are called “business environment and internal control factors.” The Basel committee has recently noted, however, that few banks “are currently able to substantiate how they quantify the impact of those factors on the capital calculation” (2006, 11). In other words, in spite of their huge analytical effort, they cannot tell what to do to reduce the risks. Much of the data collected (often of irrelevant incidents in different institutions) has minimal bearing on the important operational risks that they face. Accounting and risk expert, Michael Power suspects that the idea of operational risk may be viewed as a “fantasy perhaps, of hyper-rational management” (595). In its current format, regulators would show good judgment by removing it from regulation, banks by limiting their participation to the bare minimum.

Overly complex regulation should be opposed on the grounds that it is an infringement of liberty, unfair to smaller businesses, wasteful, and an obstacle to innovation. One possible approach is to work to place the onus on regulators to justify the benefits of both new and existing regulations against their costs to both small and large businesses.

Responsive Regulation

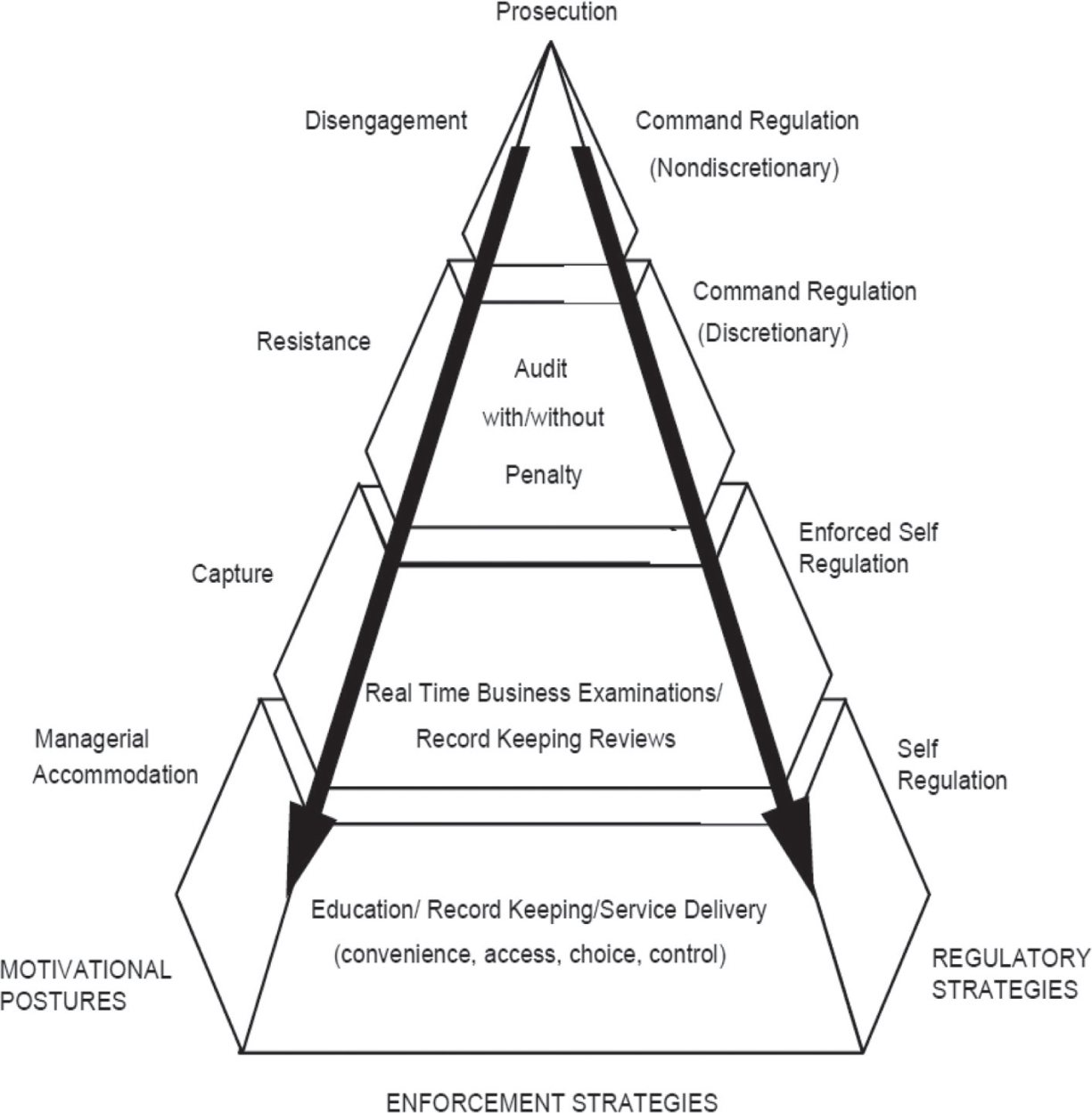

Regulators are responsive if they focus mainly on bringing out the best in people and organizations, and only use prescription where it is necessary to change behavior. Responsive regulation is self-regulation in the first place; organizations are responsible for their own risk management, ensuring that they do not harm themselves or others. Figure 3.1, borrowed from the Australian Taxation Office, sets out the ideal:

The left hand side of the pyramid represents the stances that can be adopted by taxpayers … (Braithwaite, 1995) … The right hand side presents the pyramid of regulatory strategy which is described in … (Ayres and Braithwaite, 1992).

Responsive regulation is consistent with virtue ethics in that it is more concerned with aspirations to do good rather than obeying rules that prevent evil. It must surely be more efficient in that the regulators waste less time on entities that are showing that they want to conform. It is also more effective if we accept that it garners support from those aspiring to virtue, and does address negative behavior.

One of the debates in regulation is the extent to which unsocial behavior should be punished. This is partly a matter of desert; it would be unfair for bankers who steal to get lesser sentences than burglars. There are also considerations of liberty and efficiency: whether it is necessary to take the dishonest banker off the street when society can be made safe if they are kept away from financial institutions. Both desert and efficiency come into play with the difficulty in obtaining criminal convictions. The standard of proof in criminal cases is that the matter must be beyond reasonable doubt, and wealthy individuals can employ good lawyers to sow such doubt. In civil cases the standard of proof is the balance of probabilities. The South African experience is described by the Johannesburg Stock Exchange:

Figure 3.1 Responsive Regulation3

South Africa was the first country to initiate civil prosecution of insider trading with the added advantage of compensation for those prejudiced by insider trading. …

The civil provisions of the Act have been the main tool utilised by the FSB, resulting in settlements since 1999 totalling more than R93 million. In all cases, the persons involved were named in press releases.4

They go on to report on a survey of market participants, where over three-quarters felt that the new approach had reduced insider trading. Dennis Davis reports that South African company law has followed this approach more widely in decriminalizing many offences that can be dealt with more efficiently without criminal law.

Restorative Justice and Reintegrative Shaming

Regulations ought also to be restorative in striving to get perpetrators to admit their errors, and to reintegrate them into society. It needs therefore to avoid stigmatising shaming, where the offender is labelled as a bad person and driven out of the community—at worst to set up a dysfunctional counter-culture. Braithwaite’s alternative is reintegrative shaming, where the behaviour is identified as unacceptable. Reintegrative shaming makes it clear that organizations need to deal creatively with failure, mistakes, and weakness. They need to be quick to admit to being prone to making mistakes, quick to admit them when they are wrong, and quick to forgive them.

Many huge losses can be blamed on failure to ensure that there are sufficient checks and balances—because people do not admit they are prone to failure. This is more obvious in health and safety matters: protective clothing and safety mechanisms being unused. In finance, it is perhaps more often associated with over-confidence and the way that back offices are disempowered and auditors belittled. We need to recognize that we do not demean ourselves by taking precautions and admitting to mistakes.

In many organizations, those who admit to mistakes are routinely punished for them, in some way. I am afraid that my favorite story on this may be an urban myth, but is worth telling. It was true that part of the Koeberg nuclear power station near Cape Town was shut down by a “bolt in the generator” left after routine maintenance. I cannot find it reported, but it was suggested to me that a previous technician who had reported a bolt missing had been fired. The next bolt was obviously not reported missing.

Braithwaite has a number of ideas how poisonous environments can be addressed. His Restorative Justice for Banks includes an intriguing idea about how culture might have been changed at Arthur Anderson before it contributed to the collapse of Enron, Worldcom and HIH. The issue arose in Australia in the 1990s where the firm apparently got a client into trouble and then told the tax office:

This is a rogue partner and we are going to get rid of him. We would hate you in the Tax Office to think that other partners condone what he did (2009, 445).

Braithwaite suggested that it would have been more productive for the regulator to have refused to accept this explanation, but rather to have initiated an inquiry as to whether the problem was the culture of the firm. It would surely have been critical to speak to the rogue partner. Braithwaite suggests that this partner could have played a role in what he calls a restorative justice circle, which could have led to identifying the rogue nature of the Arthur Anderson culture, worldwide. If the regulators had then responsively pursued a restorative justice approach, they might have prevented the scandals that occurred subsequently.

The fact that his best financial example is hypothetical illustrates the difficulties in implementation, but Braithwaite’s research has shown that such approaches have worked in other fields. While the process might normally be initiated by a regulator, there are opportunities for people within regulated firms to grasp the opportunity to move the culture to greater maturity.

As a Focus for Vocation

Regulators themselves need monitoring: indeed some of the problems with the industry have to be laid at their feet. There needs to be some mutual accountability, and this becomes the responsibility of academics, professional—and industry bodies and non-government organizations with a consumer or environmental mission. Regulated companies themselves can comment on inappropriate regulation. Self-interest of course muddies this mutual accountability in many ways, but it means that, whatever job you find yourself in, you will be either regulating or regulated—and the roles may switch from minute to minute.

There are therefore a number of places where individuals can make a difference in the form and application of regulations. Whether you work for one of the larger organizations or consultancies, for the national or international regulators, or in civil society NGOs or professions, there is a call to apply all your understanding to contribute to simple, effective, and human regulation and meta-regulation.

Chapter summary: We live in a system of regulatory capitalism where international companies and regulators play a role equal to government. This means power is dispersed, which is healthy, but it is increasingly dominated by large players who have contributed to the creation of excessive complexity. Responsive regulation is not based on complex rules but aims to bring out the best in people, and to ensure compliance—by reintegrative shaming if they fail.

1Details of its programmes and its Integrated Reporting Framework can be found on its website: http://www.theiirc.org, Accessed April 14,2015.

2Accessed August 30, 2014. http://www.johnkay.com/2012/07/22/finance-needs-stewards-not-toll-collectors.

3Taken from Australian Taxation Office (1998), p. 23.

4Johannesburg Stock Exchange, Insider Trading and Other Market Abuses (including the effective management of price sensitive information), Accessed August 30, 2014. https://www.jse.co.za/content/JSERulesPoliciesandRegulationItems/Insider%20Trading%20Booklet.pdf.