CHAPTER 6

Ranking Companies

More and more, people are demanding that companies in their lives be “good company.” The convergence of economic, social, and political forces that we describe in Chapters 2, 3, and 4 put us at the dawn of a new economic era in which genuine, broad-based worthiness is no longer an added bonus but a necessity. Some of the world’s largest companies are in the vanguard, pointing the way and serving as examples for others to follow. Many others, however, are laggards, apparently oblivious to these forces—and to the fact that ignoring them imperils their existence, their employees’ livelihoods, and their shareholders’ investments.

In this chapter, we quantitatively rank the publicly traded companies in the Fortune 100 on the Good Company Index and describe how you can qualitatively assess other companies outside the Fortune 100 with which you do business as a consumer, investor, or employee.

The Good Company Index

In our framework, being a good company is based on how a company acts in three different arenas: as an employer, as a seller, and as a steward of its community, the environment, and society overall. In order to (1) identify which organizations are already behaving as good companies, (2) identify which ones have a long way to go, and (3) track progress in the years ahead, we sought to create an objective system of ranking companies’ actions in these areas. We explored multiple sources of information to feed into this ranking system, seeking data that ideally had all of the following characteristics:

• Reflective of our concepts of good employer/seller/steward

• Reliable and of high quality

• Available for a large number of companies

• Timely

• Publicly available

We found something of a mixed bag—lots of information available in some areas, very little in others; systematic in some, little more than anecdotal in others. Even when available, much of the existing data is still in what might be considered the “developmental” stage—information currently exists, but we expect it will become stronger and more established in the years to come, as interest in this information increases.

In some categories, we found ourselves disappointed that no available data source met all these standards. In those situations, we selected the source(s) that came closest to meeting those requirements—or in some cases, decided to create our own database in order to collect and assess the necessary information.

Because little of the comparable information that currently exists is available systematically across different countries, we focused our initial Good Company Index rankings on companies based in the United States. We further limited our rankings to the 94 publicly traded companies in the Fortune 100. (This was also for data availability reasons; much less information is available for companies outside this group or for privately held companies.1)

In sum, we consider this first-ever Good Company Index to be an important step in the right direction. In the years ahead, we expect to both improve and update these rankings, including expanding them to a larger range of companies. (The most up-to-date information on the Good Company Index can be found at http://www.goodcompany index.com.)

Below is a brief description of the three categories of information we use for the inaugural Good Company Index.

1. Good Employer Rating. Being a good employer is foundational to being a good company. We used two publicly available sources of information in making this assessment: the Fortune list of best places to work (a positive indicator) and employee ratings collected anonymously by Glassdoor.com (can be either a positive or negative indicator).

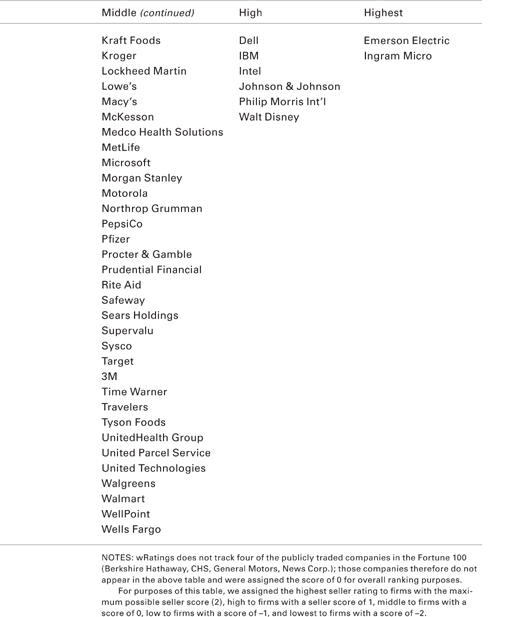

2. Good Seller Rating. Providing good value to customers and treating them fairly are basic characteristics of a good company. We used customer evaluations, rating companies by quality, fair price, and trust (graciously provided to us by research firm wRatings) to assess the extent to which companies are good to customers.2 These can be either positive or negative.

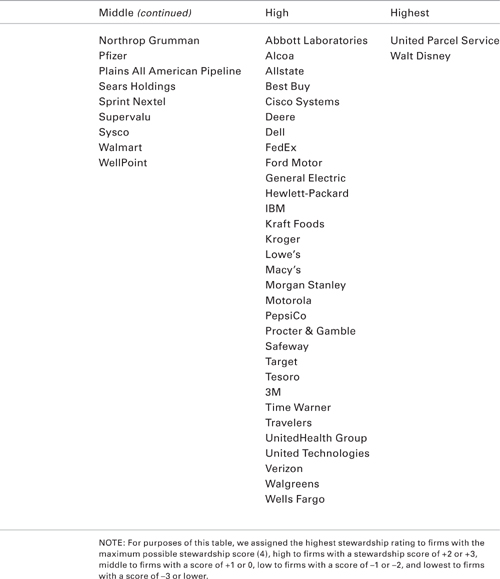

3. Good Steward Rating. Capturing quantitatively how well a firm cares for its community, the environment, and society as a whole involves multiple categories of company behavior. In the end, we considered four different measures of a company’s stewardship:

A. Environment. This can be either a positive or negative indicator, based on data from the Dow Jones Sustainability United States Index and Newsweek’s environmental ranking of the 500 largest corporations in the United States.

B. Contribution. This component is a positive indicator of a good steward, capturing the extent to which companies use their core capabilities to contribute to society (outside their day-to-day business operations). We created the database for this measure ourselves by systematically collecting information from companies’ Web sites, as well as by inviting every Fortune 100 company (by both e-mail and phone) to provide us with information on how they use their core capabilities to make contributions to society. We applied a disciplined scoring process, assigning the maximum number of points to those firms that we deemed highly systematic in using their core capabilities in service to their community or society overall.

C. Restraint. One element of being a good steward is demonstrating restraint. That is, a company ought to seek to be a good “corporate citizen” and fit comfortably into a community or society overall, rather than seek only to maximize its own well-being. Systematic information on restraint (or lack thereof) was hard to come by. But we identified good data in two areas: indicators of a company maximizing profits at the direct expense of the community and focusing disproportionately on the personal benefits derived by company executives. We used the following two measures as negative indicators of restraint:

• tax avoidance through offshore registration in tax havens (based on information from a study done by the U.S. Government Accountability Office)

• excessive executive compensation (based on data from a study commissioned by the New York Times as well as rankings available through the AFL-CIO)

D. Penalties and Fines. We believe that government-imposed penalties or fines are a clear negative indicator of a company’s behavior as steward of the community and the environment. Therefore, any company that had been assessed total penalties or fines by U.S. regulatory bodies totaling more than $1 million over the most recently available five-year period was penalized under our system (with a larger penalty for those with total fines over $100 million). No comprehensive database of such fines exists, so we compiled the data for this rating component ourselves, based on a systematic search of corporate penalties and fines.

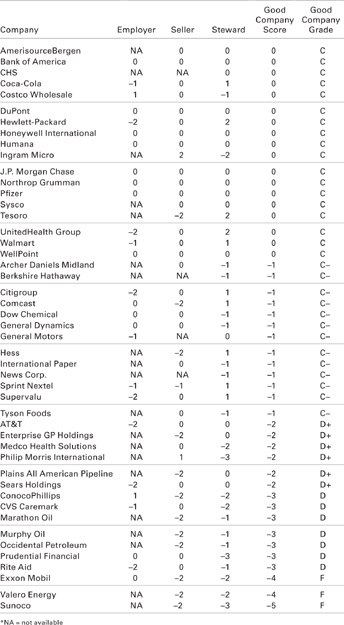

Maximum possible points range from -2 to +2 for both the Good Employer and Good Seller measures. Reflecting the greater breadth of factors covered by the Good Steward measures, the maximum possible point range for this category is broader, ranging from -3 to +4.

Combining the three categories yields a range of possible points from -7 to +8. We then use each company’s numerical score to assign a grade ranging from F for those at the bottom (those with scores of -4 or lower) up to A for companies that we believe have achieved Good Company status (those with 5 or more points). Detailed documentation and a complete listing of our rankings on each of these dimensions can be found in the Appendix.

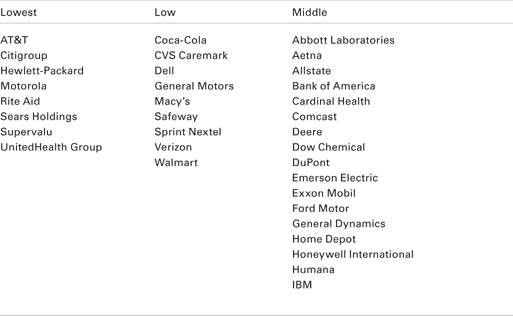

Good Employer Ratings

Being a good employer is basic to being a good company for at least three reasons. In the first place, employees are fundamental stakeholders and deserve to be treated and managed well. What’s more, over the long run it’s hard for companies to deliver great value to customers if employees are surly, disenfranchised, and/or in short supply (think Home Depot in early 2007). And if firms mistreat or mismanage workers and fail customers, the company’s capacity to deliver value to its investors and other stakeholders will suffer.

Despite the importance of being a good employer, this basic aspect of corporate worthiness is currently the most challenging dimension on which to gather information systematically. Fortune’s 100 Best Companies to Work For list provides a starting point. We assign a positive point to each of the publicly traded Fortune 100 companies that appears on this list.

At the same time, we recognize that it is an incomplete list of good employers. By definition, only 100 large organizations can make the cut, although there are almost certainly more than 100 good, big employers in the United States. And to earn a spot on the list, companies first have to choose to go to the trouble and expense of applying for inclusion.

Data from Glassdoor.com enables us to broaden our measure of good employers.3 As its name implies, Glassdoor.com allows its visitors to see inside of companies. As of early 2011, it had ratings of over 108,000 companies and their CEOs, based on anonymous employee ratings of the companies.4 (It also has salary information and the inside scoop on what job interviews are like at companies.) Why would anyone take the time to provide ratings of their employers? One of the major incentives is that you have to give to get: in order to get the greatest level of inside detail through Glassdoor.com, you have to provide information (fill out a survey) on your employer (or recent past employer). We analyzed the publicly available data on Glassdoor.com, focusing only on companies that had been rated by at least 25 employees (as of April 2010).5 One of the major advantages of Glassdoor.com is that it provides a means of identifying both highly rated and poorly rated companies, based purely on employees’ perspectives.

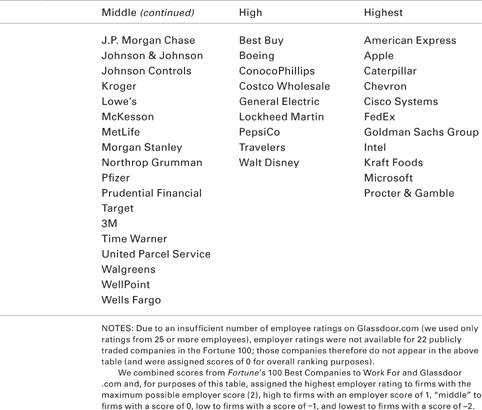

We assigned two positive points to those organizations that are in the top octile, or one-eighth, of employee ratings of the Fortune 100 companies that had at least 25 employee ratings on Glassdoor.com and two negative points to those organizations that are in the bottom octile of the ratings. We assigned one positive point to those organizations in the second octile of the Fortune 100 distribution, and one negative point to those organizations that are in the seventh (next to bottom) octile.6 Finally, we gave neither positive nor negative points to those organizations that fell in the middle (the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth octiles), or between the twenty-fifth and seventy-fifth percentile on Glassdoor.com within the Fortune 100. We have combined the evidence from these two separate sources (Glassdoor.com and Fortune’s 100 Best Companies to Work For) to assign good employer scores. (See table on the following pages.)7

One of the notable names that employees rate in the bottom one-eighth of employers is Hewlett-Packard, a company that has a long and proud tradition of being an enlightened and forward-thinking employer. The famed “HP Way” includes “trust and respect for individuals” as a core tenet.8 But under the leadership of recent CEOs, Carly Fiorina and Mark Hurd, big changes have been made. The company has laid off tens of thousands of workers in the past decade.9 Although HP under Hurd saw its stock perform well, some observers questioned whether he was doing much more than cutting costs.10 A former HP engineer told the New York Times that Hurd was “wrecking our image, personally demeaning us, and chopping our future.”11 Hurd was ousted from HP in mid-2010 in a scandal involving allegedly fudged expense reports and his relationship with an HP marketing contractor.12

One interpretation of Hewlett-Packard’s low employee rating is that its employees had long been coddled, and that by putting an end to that, Hurd had put the firm on a path to sustainable long-term profitability. Or it may be that by hacking away at employee perks and privileges, Hurd weakened Hewlett-Packard’s ability to sustain itself in the future. Only time will tell. But what can be said with certainty is that employees’ ratings of Hewlett-Packard put it near the bottom of the distribution on Glassdoor.com, and the company’s long tradition of relying on its employees as a major source of sustainable advantage has eroded.

Good Employer Ratings for the Fortune 100

Here’s something else that can be said with certainty. The employee-provided ratings available on Glassdoor.com are highly correlated with firms’ stock performance. When we compared Fortune 100 firms within the same industry and controlled for other factors (through multiple regression analysis), the most consistent factor associated with higher stock performance over three years and five years is Glassdoor.com ratings. Put another way, the higher the Glassdoor.com rating, the higher the stock performance was over three years and five years, controlling for all other factors.

Good Seller Ratings

To measure how well Fortune 100 firms treat their customers, we used 2008 and 2009 data that was provided to us by research firm wRatings. wRatings collects a treasure trove of data on customers’ ratings of 17 separate aspects of their experiences and perceptions of thousands of firms.13 Hedge fund managers subscribe to wRatings because it provides them with a leading indicator of where a firm’s stock price is headed; a negative change in customers’ ratings is generally followed in three to six months with a decline in a firm’s stock price; a positive change is likewise followed by an increase. Similarly, CEOs use wRatings to track their competition, so they know in advance when a rival is about to get a leg up on them. We worked with wRatings CEO Gary Williams to boil their vast database down to three essential aspects that we believed would summarize a company’s standing as a good seller: quality, fair price, and customers’ trust in the company.

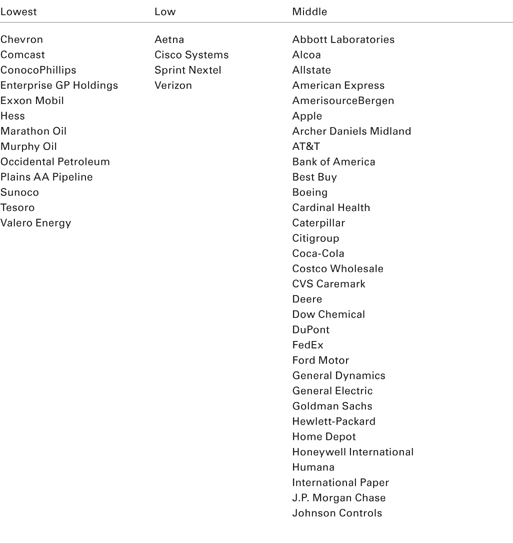

Based on this three-dimensional measure of customers’ ratings, relative to all of the approximately 4,000 firms in wRatings’s database, we then assigned two positive (or negative) points to those Fortune 100 firms that are in the top (or bottom) octile of wRatings’ overall ranking on these three dimensions. We also assigned one positive (or negative) point to those organizations in the second (or seventh) octile of wRatings’s overall distribution.14 Organizations that fell in that middle half (between 25 percent and 75 percent within wRatings’s larger database) are assigned neither positive nor negative points and are included in the middle column of our Good Seller Ratings table on pages 100 and 101, which summarizes the customer ratings from this analysis.15

The mediocrity of customers’ experience with most Fortune 100 firms is one conclusion that jumps out of the table. Only two of these firms—Emerson Electric and Ingram Micro—are in the top one-eighth of the overall wRatings distribution. At the other end of the spectrum, Fortune 100 firms are proportionally represented at the bottom of customers’ experience.

Also notable is the poor regard with which customers hold the big oil and gas firms. No doubt, this is tied up with these firms’ activities that result in large penalties and poor stewardship of the environment, a discussion of which follows.

Good Steward Ratings

We take a broad view of stewardship, which includes not only firms’ environmental records, but also the extent to which they show a serious commitment to being of service to the world and are able to demonstrate a degree of restraint (or conversely, an absence of greed) and avoid major penalties and fines. As noted above, the measures that we use for each of these aspects of stewardship are as follows:

• Environment. We assign a positive point for inclusion in the Dow Jones Sustainability United States Index and Newsweek’s environmental ranking of America’s 500 largest corporations. We assign a positive point to companies in the top 25 percent in Newsweek’s environmental ranking of America’s 500 largest corporations and a negative point to those in the bottom 25 percent.

• Contribution. We assign a positive point to organizations that use their core capabilities to contribute to society and another positive point to those organizations that do so in a systematic way.

• Restraint. We assign a negative point to organizations whose CEOs have compensation we deem excessive (based on a study commissioned by the New York Times as well as rankings available through the AFL-CIO)16 and a negative point to organizations that avoid paying taxes through offshore registration in tax havens (based on a 2008 study by the U.S. Government Accountability Office).17

• Penalties and Fines. We assigned a negative point to firms that were assessed total penalties or fines from $1 million through $100 million (between 2005 and 2009). Two negative points were assigned to companies with total fines and penalties of more than $100 million over the same time period. Our research included a systematic review of fines by U.S. regulatory bodies as well as a scan of headlines for major fines and penalties meted out by European Union regulators.

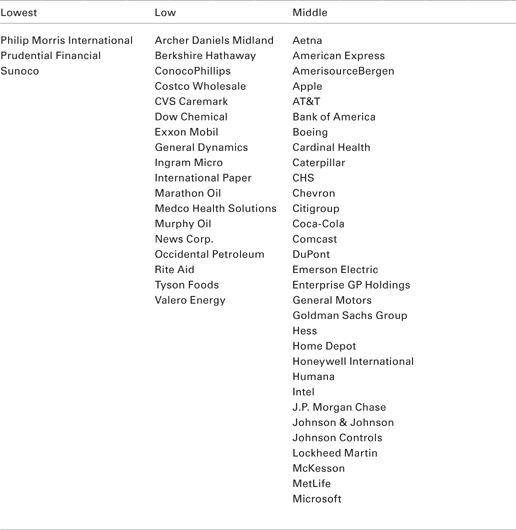

The findings from our stewardship analysis are summarized in the table on pages 102 and 103.

We were surprised by a number of the findings with respect to stewardship. First, we were pleased by the extent to which Fortune 100 firms are systematically using their core competencies to do good in the world. For example, Kraft Foods recently pledged $180 million over three years to get more food—and better nutrition and information—to children and families.18 And IBM provides its speech recognition technology to help both children and adults improve their literacy skills.19 We assigned the maximum contribution points (two positive points) to a majority—56—of the publicly traded Fortune 100.20

Good Seller Ratings for the Fortune 100

Good Steward Ratings for the Fortune 100

Conversely, we noted a large percentage of Fortune 100 firms—at least 59 of them—appeared to be using offshore tax havens to avoid paying taxes.21 Some would argue that publicly traded companies actually have a fiduciary responsibility to shareholders to lawfully minimize their tax liabilities and therefore should actively seek out tax havens. But we don’t buy this thinking, and we suspect that the vast majority of taxpayers would side with us. This is a behavior that was perhaps acceptable in the past but won’t be tolerated in the future.

With regard to our other restraint measure—CEO compensation—we came to the by-now-unsurprising conclusion that a CEO’s compensation has little to do with his or her company’s performance. News accounts over the past several years have pointed out example after example of executives who are highly paid yet are underperformers.22 As is the case with other forms of greed, we expect that this too will be much less tolerated in the future than in the past.

We were dismayed at the large number of penalties and fines levied against Fortune 100 firms. Although these fines do not necessarily indicate that firms have broken the law (since they often agree to pay the fine without admitting to illegal activities), it also seems reasonable to conclude that where there’s smoke, there’s often fire.

Some of the cases that were assigned two negative stewardship points are well known, such as the European Union’s $1.3 billion fine of Microsoft for its sales tactics.23 Others also come as no surprise, such as the large numbers of fines and penalties paid by firms in the oil and gas industry. Some of the other companies’ assessed penalties are more notable, including Johnson & Johnson and renowned Berkshire Hathaway. A subsidiary of Berkshire Hathaway was found guilty of entering into a fraudulent scheme to manipulate AIG’s financial statements.24 And a Johnson & Johnson subsidiary was found guilty of illegal kickback schemes.25 (It should be noted that the company called this illegality to the attention of regulators. However, as of early 2010, a similar action was pending against another of Johnson & Johnson’s subsidiaries.26) Johnson & Johnson also has seen its reputation tarnished by major product recalls and criticism from government officials.27

Some might question whether a parent company should be held fully accountable for the actions of its subsidiaries. But we think that misses the point. The parent company is responsible for the actions of its subsidiaries, and if the burden of monitoring those subsidiaries so that they abide by the law is too great, then the company has grown too large (and perhaps too greedy). The blame falls to both the subsidiary and its parent company.

Others might argue that the reason so many large companies break the law (or alternatively, enter into consent decrees) is because it is simply impossible for them to abide by the law. This perspective would hold that the large number and magnitude of penalties and fines paid by Fortune 100 firms proves that the law is an unreasonable constraint on commerce.

We don’t accept this point of view either. The corporate activities that result in these penalties and fines are often serial in nature. Many are for repeated and/or egregious violations of the law—not for an occasional minor infraction here and there. (We have accounted for this issue by focusing only on firms that had more than $1 million in fines and penalties.)

As we compiled and assessed the database of major corporate penalties and fines, we came to four conclusions:

1. Compiling this information is hard work. There is no centralized source that makes information about rule violations by companies and resulting punishments easily available. That should not be the case—it can and should be remedied—a point that we return to in Chapter 10.

2. While we are confident that we have identified the major penalties and fines levied by federal regulatory bodies in the United States, we are equally confident that there are other, smaller penalties and fines that we have missed. We did not, for example, examine the penalties assessed by state regulators. Hence, our final calculations of fines and penalties among the Fortune 100 almost certainly understate them for some companies.

3. Breaking the law is a part of how some of these firms have gotten to be, so big. By engaging in dangerous cost cutting, fraudulent financial practices, and/or anticompetitive practices, these firms have gotten a leg up on their competition and taken advantage of society. While they might not be too big for their own good, some have clearly become too big for our own good.

4. Nonetheless, many of the largest firms have managed to grow large through more worthy means: by scrupulous attention to and compliance with the law. As the world becomes increasingly transparent, and law-breaking or other questionable behavior becomes more readily detectable, we predict these are the firms that will prosper.

Overall Good Company Grades

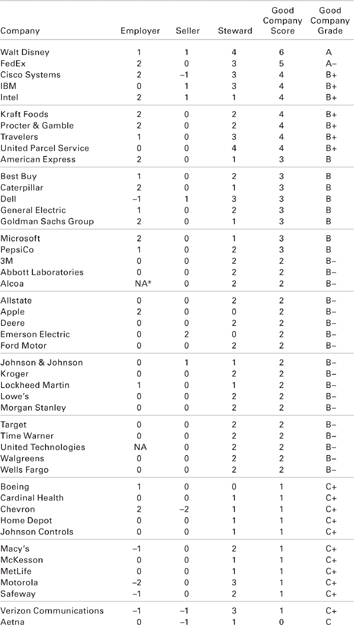

The final step in creating the Good Company Index consisted of consolidating the employer ratings, seller ratings, and steward ratings, and converting the numerical scores to grades. This led us to the combined Good Company Index, summarized in the table labeled Overall Good Company Index Grades for the Fortune 100 on pages 108 and 109.28

There is good news and bad news in this table. The bad news is that only two Fortune 100 firms (Disney and FedEx) received a grade in the A range (thereby meeting our definition of a Good Company) while a distressingly high 16 of the Fortune 100 received either a D or F. The good news is that 35 of the Fortune 100—a little over one-third—received a B- or better.

Some of the findings may come as a surprise—such as Walmart’s grade of C (for those who love to hate it). While there is much to dislike about Walmart—its treatment of its employees, the significant penalties and fines that have been levied against it, and the extremely high compensation of its CEO—there is also much to admire. As discussed in earlier chapters, Walmart is making progress. It is a leading green company, and it uses its considerable resources to contribute to making the world a better place. In early 2010, for example, Walmart announced a massive $2 billion campaign to help alleviate hunger in the United States.29 And unlike the majority of its Fortune 100 brethren, it has avoided using tax havens. We believe Walmart has been pushed by the convergence of economic, social, and political forces discussed earlier and has become a more worthy organization. It still has a long way to go but seems to be headed in the right direction.

Similarly, Home Depot—which received a C+—has come a long way since its flaws were very publicly disclosed and discussed by thousands of its disgruntled customers in 2007 at MSN Money’s Web site. It earns average scores on both employee and customer ratings, and it consistently uses its core capabilities to make contributions to communities. For example, Home Depot provides disaster preparedness clinics at its stores.30 The only strike against it in our scoring system is a $1.3 million penalty in 2008 for alleged violations of the Clean Water Act at its construction sites. Like Walmart, it’s coming along. It’s within striking distance of catching up to Lowe’s, which received a grade of B–.

With the exception of Chevron, which received a C+, the oil and gas firms received Ds or Fs. The unprecedented environmental disaster caused by BP in 2010 will almost certainly hasten the changes that society will demand of these firms. But even without fundamentally changing how they operate, they would be well served by taking some relatively simple actions. For example, they could stop using offshore tax havens, reduce their CEOs’ compensation, and begin to make more meaningful contributions to the communities in which they operate.

Goldman Sachs is a special case. In our grading system, Goldman Sachs received a B, a grade that some might find overly generous in the wake of the company’s behavior during the housing meltdown and financial crisis. But for years, Goldman earned top marks for corporate social responsibility. It has been lauded as a good employer and a sustainability leader. And it has been generous with its philanthropy—most notably a massive $500 million donation to charity it made in early 2010. So once we took into account the company’s whopping $550 million penalty paid to settle charges that it defrauded investors in a mortgage securities deal, a B is where Goldman fell on the grading continuum.

But we see Goldman’s grade of B, rather than an A, as a good example of how the bar is rising for businesses. It’s now clear that the kind of “responsibility” Goldman Sachs and others have practiced is no longer good enough. Take Goldman’s giant gift. It came in the wake of mounting public outrage at Goldman for betting against clients, possibly worsening the Great Recession, and setting aside billions in pay while millions of families struggled financially. In other words, the hefty donation appeared reactive—Goldman responding to social pressures as opposed to acting out of a genuine sense of community stewardship.

Overall Good Company Index Grades for the Fortune 100

Indeed, the hundreds of documents unearthed during government probes proved without a doubt that Goldman has been far from thoroughly worthy. One e-mail from a senior Goldman executive captures the way the company, despite its many decent qualities, was quite willing to peddle crummy products to customers: the executive described the sale of a mortgage-related security as a “shi**y deal.”31

This unworthiness as a seller helped persuade us to make an exception to our index calculations. The mid-2010 news of Goldman’s penalty and settlement with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission arrived after our deadline for tallying fines and penalties paid by the Fortune 100. If we hadn’t extended the cutoff point for Goldman Sachs, the company would have earned our top grade of A. Given the wrongs at Goldman in recent years, we hope readers will agree this was the right decision.

Then there are the two Fortune 100 firms that unambiguously qualify as Good Company—Disney and FedEx. FedEx has delivered the goods as a good company. The package-shipping titan earned strong marks on Glassdoor.com and has made Fortune’s 100 Best Companies to Work For list 12 of the past 13 years.32 The company narrowly missed earning a customer service point in our ranking system, and it has consistently outperformed rivals United Parcel Service and the U.S. Postal Service on the American Customer Satisfaction Index.33 What’s more, FedEx has proved itself to be a sound steward. This includes regularly offering its transportation and logistics expertise during disaster-relief efforts.34

Even with its classification as Good Company, FedEx has a black mark against it because of its use of at least a dozen subsidiaries in offshore tax havens. And there has been controversy over the way FedEx classifies many of its drivers as independent contractors rather than employees.35 While it stands heads and shoulders above most of the Fortune 100, it too has improvements to make.

Disney deserves special comment. It is the only Fortune 100 firm that has above-average scores in all three of the major ratings—employees, customers, and stewardship—while simultaneously having no negative points against it. For example, we did not find significant penalties or fines levied against the firm.36 Disney scored six of the maximum possible eight points in our Good Company ranking system. It’s an impressive performance.

As we sliced and diced the data from the Good Company Index, it became apparent to us that goodness does, indeed, already have its rewards. Companies with higher scores than industry peers on the Good Company Index had stronger stock market performance than their counterparts over periods of one, three, and five years (see sidebar).

How to Assess the Companies You Do Business With

The quantitative ranking provided above is a useful starting point for assessing the largest U.S.-based companies. But you do business with many other companies not on this list, and for which there isn’t enough (or any) publicly available information for you to create your own ranking. So for these companies—from the “mom and pop” corner dry cleaner to the supermarket where you buy food—we suggest using a qualitative assessment process.

The indicators summarized above are tangible traits. They can be measured in pay levels, policies, and emissions. From the scores of interviews that we did in our background research, we identified five less-tangible attributes that form the foundation for being a good employer, good to customers, and a good steward.

• Reciprocity is the shift from an exploitation mindset to one of cultivation, of seeking mutual benefit through win-win interactions.

• Connectivity refers to the fundamental need (and emergent power) of human beings to be connected, informed, and effective.

Good Companies Outperform in the Stock Market

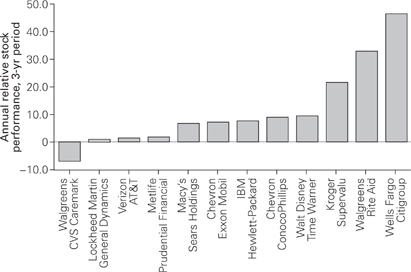

When we compared pairs of Fortune 100 companies within the same industry, we found that those with higher scores on the Good Company Index outperformed their peers in the stock market over periods of one, three, and five years.

For example, over the previous three years, the company with the higher Good Company Index score performed, on average, more than 4 percentage points better in the stock market than the paired company from the same industry with the lower Good Company Index score. (For the one-year and five-year periods, the comparable annual outperformance is 2 percentage points in each of the periods.)

By stock market performance, we mean the percentage change in share price (up or down), after incorporating any dividends paid. The analysis included 33 pairs of same-industry companies (those for which stock market data was available for all three periods and for which there were no missing elements among the components of the Good Company Index scoring system). Twenty-one of the pairs involved differences of 1 or 2 points on the Good Company Index; the remaining 12 pairs involved differences of 3 points or more. (Since Dan and Laurie are both registered investment advisors, it’s important for us to add the customary precaution that past performance is not a guarantee of future performance.)

Most of the differences in stock performance occur when the difference in Good Company scores between the two paired companies is three points or greater, which corresponds to at least an entire letter grade in our overall ranking system. Companies that outscored their peers by three points or more on the Good Company Index outperformed them, on average, by 11 percentage points annually in the stock market over the previous three years. (For the one-year and five-year periods, the comparable annual outperformance is 5 percentage points and 6 percentage points, respectively.) The relative annual performance of each of these twelve industry-matched pairs over the three-year period is displayed in the figure on the opposite page.

Relative annual stock performance, previous 3 years, for industry-matched pairs with Good Company Index score differences of 3 or more

Company Pairs

(company with higher Good Company Index score listed first)

NOTE: Relative performance for each pair is calculated as stock performance of company with higher Good Company score minus performance of company with lower Good Company score.

For example, Chevron and ConocoPhillips are both major oil and gas companies. Chevron earned a Good Company Index score of +1 (C+), while ConocoPhillips scored -3 (D), a difference of 4 points, or more than one full grade. Over three years, Chevron outperformed ConocoPhillips by 9 percentage points annually. This example, combined with the results from the other industry pair cases, suggests that the better companies are when compared to their peers, the more they will outpace them. Goodness comes with a tailwind.

• Transparency means a willingness to share information and expose the reasoning behind decisions with stakeholders.

• Balance means the wisdom to make judgment calls amid competing priorities.

• Courage refers both to taking risks and doing what is right, despite possible adverse consequences in the short run.

RECIPROCITY

Reciprocity is a core attribute of a good company. Think about the difference between Southwest and United Airlines. The organizations’ commitment to reciprocity—or the lack thereof—shows up in both employee and customer relations. Southwest is near the very top of Glassdoor.com’s employee ratings, whereas United is near the bottom.37 Here’s one illustrative example of why this is so. In the crisis that followed the September 11 destruction of the World Trade Center, the major airlines laid off 16 percent of their workforces. Southwest avoided layoffs altogether.38 And although Southwest is among the most unionized of airlines, management consistently has a constructive and respectful relationship with labor.

Southwest’s focus on reciprocity permeates all of its relationships. And not coincidentally, in 2010 Southwest had the top customer satisfaction ratings in the airline industry, while United had the worst.39

Need to cancel a reservation on a Southwest flight? No problem. Even with the lowest-price class of ticket—the “Wanna Get Away” fare—you can quickly go online, cancel the ticket, and your full payment goes into an account that you can instantly access for your next ticket on South-west.40 But if you need to cancel your reservation with United, you have to call them (unless you have purchased an expensive refundable ticket), wait for a customer service representative (waits of over 30 minutes are not uncommon in bad weather), and pay a cancellation fee of $150 to have your original payment applied to a new flight.41

United charges you this fee because they can—they’ve got your money and they don’t have to give it back to you. Southwest chooses not to do so—even though they could—because they are committed to reciprocity.

Reciprocity plays itself out in ways large and small in the companies that you deal with day in and day out. It is the give and take between human beings that makes life better, but that is all too often lost because of “corporate policy” (as in when the customer service representative tells you that he or she cannot do what you are requesting because corporate policy does not allow it). Good companies, like Southwest Airlines, realize that they need to build reciprocity into their day-to-day operations—to base corporate policy on the principal of reciprocity.

CONNECTIVITY

Human beings have a fundamental desire for connectivity. And since technology enables new ways for people to be connected with one another, people’s expectations have risen. Both employees and customers increasingly expect the organizations in their lives to provide them with more and better ways to connect to improve the quality of their lives.

Kaiser Permanente is leading the way in health care—an industry that is badly in need of finding new and better ways of providing its services efficiently and effectively. Kaiser uses technology to provide its customers with easy “24/7” access that they can use to schedule appointments with doctors at the customer’s convenience (imagine that!), access their health-care records, see results from diagnostic tests as soon as the lab has completed them, and send questions via e-mail to their doctors.

From the customer’s perspective, the system seems to be designed for their convenience, rather than that of the physicians’. It enables customers to take much more active ownership of their health care, rather than being forced to passively wait until the system chooses to deliver it.

But the system is also designed to enable employees at all levels in the organization—from the clerk who checks a customer in to a busy doctor attempting to achieve a modicum of work-life balance—to be more effective and efficient. Imagine this scenario (which actually happened to one of the authors): You are checking in to get the necessary vaccinations for an upcoming trip to a far-off, developing nation. Since this is not routine preventative care, you will be charged for it. You hand over a check for $30. “But wait,” the clerk says, “I see that the only shot you need is a tetanus shot—that’s routine preventative care, for which there is no charge.” With a pleased smile, the clerk returns the $30 check you just wrote. There is also a pleased (and surprised) smile on your face. Or consider the doctor who sends you an e-mail at the end of her busy day that answers an urgent question you have. The doctor has saved both of you the trouble of an urgent visit the next day.

Connectivity has made everyone in these exchanges better off by reducing costly administrative errors and unproductive use of time, resulting in higher quality outcomes at lower costs.42 The technology that has fueled this connectivity enables people to be more informed and effective, and in so doing, makes life better.

TRANSPARENCY

Transparency—the willingness to share information and to expose the reasoning behind decisions with stakeholders—builds trust and good will. In its purest form, transparency takes the form of an open-book policy. When Habanero, a Vancouver-based Web-consulting firm, adopted an open-book policy in 2002, its CEO Elliot Fishman had to take the time to train his employees to read profit-and-loss statements. Perhaps more importantly, he had to trust them not to leak information inappropriately to outsiders, including competitors.

When the firm had to find ways to cut costs during the Great Recession, his investment of time and trust paid off handsomely. Employees volunteered lots of good cost-savings ideas, both large and small. Later, it became apparent that even this was not enough, and that 15 percent of the staff had to be laid off and bonuses eliminated. “There were no hiccups because people saw it coming,” Fishman said. “Being transparent leading up to our decision set us up to deal with the fallout.”43

Transparency with customers also has its payoffs. McAlvain Group of Companies, an Idaho-based construction firm, prominently promotes its commitment to transparency on its Web site as follows: “Our open-book accounting and line-item budgeting allows our clients to identify where project costs reside by division. From design through final completion, we provide cost-saving options by analyzing schedules, means and methods, alternative construction, and constructability surveys …” 44

Their CEO, Torry McAlvain, says, “In the construction business there are so many ways to make money that you don’t feel good about. Our open-book policy is a way to make sure that we feel good about what we do. It promotes trust with our customers, and it drives accountability throughout our employee base. It’s knit into the fabric of the organization. And it works—it’s how we win business.”45

BALANCE

Balance is more of an Eastern concept than one from the West, where businesses historically have been more focused on progress. But the ability to achieve equilibrium in different business arenas is increasingly important to companies throughout the world. They must balance the interests of different stakeholders, sometimes-conflicting values, and short-term gains against long-term goals. Among the firms that have best managed to create harmony amid discordant demands is Seventh Generation. The household product maker’s very name builds balance into the business. It is a reference to a concept from the Native American Iroquois people: that decisions today ought to consider the effects on descendants seven generations into the future.

Seventh Generation puts this principle into practice by balancing consumer convenience and manufacturing ease with environmental and community stewardship. The firm isn’t perfect in achieving this counterpoise. As of the publication of its “Corporate Consciousness Report” in 2009, it had not replaced a nonbiodegradable synthetic polymer in its automatic dishwashing powder and gel.46

On the other hand, Seventh Generation has eliminated synthetic fragrances from all its products and backed a push to grow palm oil—a major ingredient in cleaning products—more sustainably.47 It also has dared to try to change consumer behavior. Among the company’s campaigns in 2008 was a “Get Out of Hot Water” effort. It called attention to the fact that 90 percent of the energy expended when washing clothes is used for heating water, and encouraged consumers to do the laundry in cold water instead.48

So far, Seventh Generation is managing to be both a sound steward and a successful business. Its sales soared 51 percent in 2008, despite the Great Recession. Sales fell slightly in 2009 but climbed in early 2010, and Seventh Generation expected 20 percent growth for the year.49

Goldman Loses Its Good Name

The scandal that surrounded Goldman Sachs in 2010 captures the danger of being a less-than-thoroughly worthy company.

Prior to Goldman’s public flogging for putting its own interests ahead of clients’ and for possibly contributing to the Great Recession with casino-like operations, the company had built an impressive track record of corporate responsibility and business success.

Among Goldman’s honors were a top-10 ranking in Fortune magazine’s 2009 list of the best companies to work for in America, a place on the Dow Jones index for sustainability leaders in the United States, and regular appearances on Fortune’s lists of the most admired companies.57

But these achievements shrank in importance as the firm’s trading and pay practices came under scrutiny in 2009 and 2010. Amid tough economic times for many people and after receiving an emergency loan from the U.S. Government, Goldman Sachs sparked public fury by setting aside billions in pay for its bankers in 2009.58 In April 2010, the company was slapped with a civil lawsuit by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for allegedly defrauding investors in connection with a mortgage-related transaction.59 And documents that surfaced thanks to a Congressional hearing all but convicted Goldman in the court of public opinion.

According to the internal documents and a New York Times story, Goldman decided to “short”—or bet against—the mortgage market by early 2007.60 In a December 2006 e-mail, Goldman executive Fabrice Tourre wrote, “We have a big short on …” 61 But, the Times reported, Goldman did not reveal its short position even as it sold mortgage-related securities to clients.62 And, according to the SEC suit, it hid from clients the fact that a particular mortgage-related security was constructed with the significant involvement of a hedge fund that bet against the security.63

On April 27, 2010, Goldman CEO Lloyd Blankfein testified to Congress, “We didn’t have a massive short against the housing market and we certainly did not bet against our clients.” 64 But taken as a whole, the evidence indicated otherwise. It showed Goldman to be a company looking out for itself—magnifying risk in the financial system and willing to sell out clients to boost its own profits.

Such unworthiness did not go unpunished. Goldman settled the SEC case in mid-2010, agreeing to pay a record $550-million penalty and admitting that its marketing materials for the mortgage product contained incomplete information.65

Earlier in the year, Goldman announced a $500 million contribution to charity.66 That amount dwarfs the typical philanthropic donation companies make annually. But the gift came across as a response to anger at Goldman. And the generosity didn’t earn the firm much praise—a sign that corporate “responsibility” is no longer good enough. In the emerging Worthiness Era, gross examples of greed will not be tolerated, even by companies that in other respects are decent. A report from Harris Interactive in early 2010 found Goldman Sachs to have the fifth-lowest reputation of the 60 most-visible companies in the United States.67

Goldman has tried to recover its good name. In January 2011, it released a report outlining a series of internal reforms in areas including client service, transparency, and training.68

Still, Goldman’s earnings for 2010 fell by nearly half.69 A hiccup for the firm or a sign of long-term trouble?

“We have been a client-centered firm for 140 years and if our clients believe that we don’t deserve their trust, we cannot survive,” Blankfein told Congress.70 Whether Goldman has been client-centered for all of its 140 years is debatable. But Blankfein was on the mark about client trust and survival. Goldman—good in so many ways—may ultimately wither because of its bad behavior.

You might think of Seventh Generation employees and executives as yogis. Yogis can stand on one leg for an eternity with a placid expression, but they are concentrating—working hard—to achieve that balance. In fact, Seventh Generation’s growth during the recession took a toll on employees such that “our work/home balance is clearly out of whack,” company cofounder Jeffrey Hollender wrote in the company’s 2008 “Corporate Consciousness Report.”50

Even this admission of workplace imbalance—rare among companies—is a positive sign. Seventh Generation takes balance seriously. That’s good for it and all its stakeholders.

COURAGE

Good companies aren’t for the faint of heart. They take courage, especially in this transition period when companies can continue to get a leg up on worthier rivals with low-road tactics. For a portrait of corporate courage, consider Ultimate Software and its CEO Scott Scherr.51

Scherr hasn’t laid off a single employee since he founded the Westin, Florida-based HR and payroll software company in 1990. Ultimate has stuck by its employees in both good times and bad, including a stretch from 2000 to 2004 when the company lost more than $45 million.52 Scherr also avoided giving pink slips to any of his nearly 1,000 employees during the Great Recession, even though Ultimate posted losses in 2008 and 2009 totaling about $4 million.53

“We never threw anybody under the bus,” Scherr says. “The test is always the tough times.”

Some might call Scherr foolish rather than brave. Why not streamline the company during downturns, cutting out dead wood and avoiding the risk of a bloated ship sinking? But Scherr and Ultimate obsess on hiring only A players. And while a small fraction of the workforce is fired for performance problems every year, Scherr views the layoff aversion as a way to preserve talent. To him, those people are the heart of Ultimate’s success.

“The business is there to take care of the employees, and the employees are there to take care of the business,” he says.

Ultimate also refused to change its practice of giving all employees stock-based compensation, despite the change in accounting rules a few years ago that makes companies’ net income look worse when doling out stock options.54

Despite the recent losses, other signs show the company’s gutsy reciprocity is paying off. Ultimate’s revenue climbed from $179 million in 2008 to $197 million in 2009. Customer retention that year was 97 percent.55 And without any mandate from management, Ultimate’s employees trimmed back travel and expense costs during the recession to a “material” extent, Scherr says.

Ultimate ranked as the best medium-size company to work for in America in both 2008 and 2009.56 When accepting the 2009 honor, Scherr laid out his philosophy: “The true measure of a company is how they treat their lowest-paid employee.”

That’s a good yardstick for worthiness—and performing well on it requires the kind of courage Scherr and crew have shown.

The more business you can do with organizations that cultivate these five characteristics, the better off we all will be.

CHAPTER SIX SUMMARY

We quantitatively rank the publicly traded companies in the Fortune 100 on a Good Company Index and describe how you can qualitatively assess other companies outside the Fortune 100 with which you do business as a consumer, investor, or employee.

The Good Company Index

The Index incorporates three subcomponents—ratings on company behavior as an employer, seller, and steward.

• To rate employers, we use information from Fortune’s list of the 100 Best Places to Work For and employee ratings collected anonymously by Glassdoor.com.

• To rate sellers, we use customer evaluations of quality, fair price, and their trust in the company (provided by research firm wRatings).

• To rate stewards, we consider four measures of a company’s stewardship:

1. Environment—based on the Dow Jones Sustainability United States Index and Newsweek’s environmental ranking of the 500 largest corporations in the United States

2. Contribution—our assessment of the extent to which companies use their core capabilities to contribute to their community or to society overall, based on our own data collection

3. Restraint—there are two areas related to companies’ restraint for which data is available: tax avoidance through offshore registration in tax havens (based on a 2008 study done by the U.S. Government Accountability Office) and excessive executive compensation (based on a study commissioned by the New York Times as well as rankings available through the AFL-CIO)

4. Regulatory penalties and fines—compiled by the authors through a systematic search for each company

Overall Good Company Grades

• Only two companies—Disney and FedEx—earned an A, thereby meeting our definition of a Good Company.

• Three companies—Valero Energy, Exxon Mobile, and Sunoco—received a grade of F.

• A comparison of Fortune 100 firms within the same industry reveals that firms that had higher scores on the Good Company Index had stronger stock market performance than their counterparts over one-, three-, and five-year periods.

How to Assess the Companies You Do Business With

We identified five less tangible attributes that form the foundation for being a good company that you can use to assess the companies with which you do business:

1. Reciprocity is the shift from an exploitation mindset to one of cultivation, of seeking mutual benefit.

2. Connectivity refers to the fundamental need (and emergent power) of human beings to be connected, informed, and effective.

3. Transparency means a willingness to share information and expose the reasoning behind decisions with stakeholders.

4. Balance means the wisdom to make judgment calls amid competing priorities.

5. Courage refers both to taking risks and doing what is right, despite possible adverse consequences in the short run.