Knowing Your Manager—and Yourself

Managing up is a constant process. It takes keen observation and a willingness to adjust your behavior on a daily basis. But once you and your boss have built a trusting relationship on a solid foundation, cultivating it becomes easier and less time-intensive. The first step in getting to that happy place is identifying where you and your boss stand, both professionally and personally.

Beyond your obligations to each other, you and your manager have specific roles to play and people to whom you’re accountable. In short, you each have a web of complex relationships to maintain and responsibilities to fulfill. Acknowledging those realities can help you see the world from your boss’s point of view.

It’s also essential to understand your manager’s priorities and pressures—and to map them against your own. Locate points of overlap and those of potential conflict, perhaps by marking them on an organizational chart. The visual evidence can expose hidden risks and opportunities in collaborating with your manager.

For example, look for chances to support your boss in work she’s doing for her own manager. Ask how you can help—and suggest ideas of your own. Suppose, for instance, she could use an extra set of hands on an exciting project with a tight deadline. Propose taking on certain tasks that complement your skills and interests. You’ll get to participate in higher-level work, your boss will get more done, and throughout the project you’ll be showing—not just telling—her that your goals and hers go hand-in-hand.

Of course, differences in power can make some subordinates, especially those who are themselves managers, react in unhealthy ways. Management experts John Gabarro and John Kotter highlight two problematic responses to a boss’s authority:

• Counterdependency: when you unconsciously resent your boss, perhaps even see her as an institutional enemy. Counterdependent subordinates may start arguments (especially with authoritarian bosses) just for the sake of fighting.

• Dependency: when you swallow objections—or anger—and comply even when your boss makes a poor decision. Dependent subordinates stew rather than express honest opinions.

If you recognize a bit of yourself in either of these profiles, consider how your natural reaction to authority in general may be damaging your relationship with your boss. Then think about ways to respond more constructively, as in the previous example, where offering to help your boss leads to a more efficient division of labor and the chance to contribute to a desirable project.

Strengths and weaknesses

Once you know your manager’s strengths, you can find ways of working together that bring out the best in both of you. You can also appreciate how she’s using those strengths to support team and company goals—and tactfully promote those accomplishments to others in the organization. Bosses appreciate, and often reciprocate, that kind of advocacy.

Though you may have a pretty clear idea of what makes you a good employee, pinpointing your manager’s strengths can be tougher to do. You’ll certainly want to observe her as she pursues objectives and interacts with others. You can also get valuable insights by talking with coworkers who know your boss better than you do, especially if you’ve just started reporting to her.

Having done that bit of informal research, list your manager’s strengths alongside your own and note the similarities and differences. Points of overlap—say, you’re both analytical and data driven—can spark camaraderie and strengthen your relationship. Differences needn’t be seen as problems—they can signal opportunities to complement your manager.

You may, at times, bemoan your boss’s shortcomings or even feel thwarted by them. But that’s a prescription for frustration. Instead, think of recognizing her weaknesses as an important step toward achieving your common goals. Figure out where your manager needs assistance, and step up to offer it.

For example, if your manager has a tough time meeting deadlines, identify the obstacles that typically stand in the way. Offer to tackle those tasks for her if they’re in your purview—or to perform a supporting role if they’re not. Even a friendly reminder a week or so ahead of a deadline can go a long way. A collegial, in-person nudge is more likely to prompt action than a sterile ping on an electronic calendar.

Zero in on your own weaknesses, as well. To develop an effective partnership, you need to know when to lean on your manager, not just when she can lean on you. If your weaknesses and hers overlap in some areas, those may be points of “friendly com miseration” on an emotional level. On a practical level, they may reveal where the two of you need outside support.

Work styles

As Carla did in our earlier example, ask your manager how she likes—and does not like—to operate. It’s important to know her general preferences (“Stop by my office rather than sending me e-mail”) and to scope out specifics (“Updates on this project should come to me every Thursday by noon”).

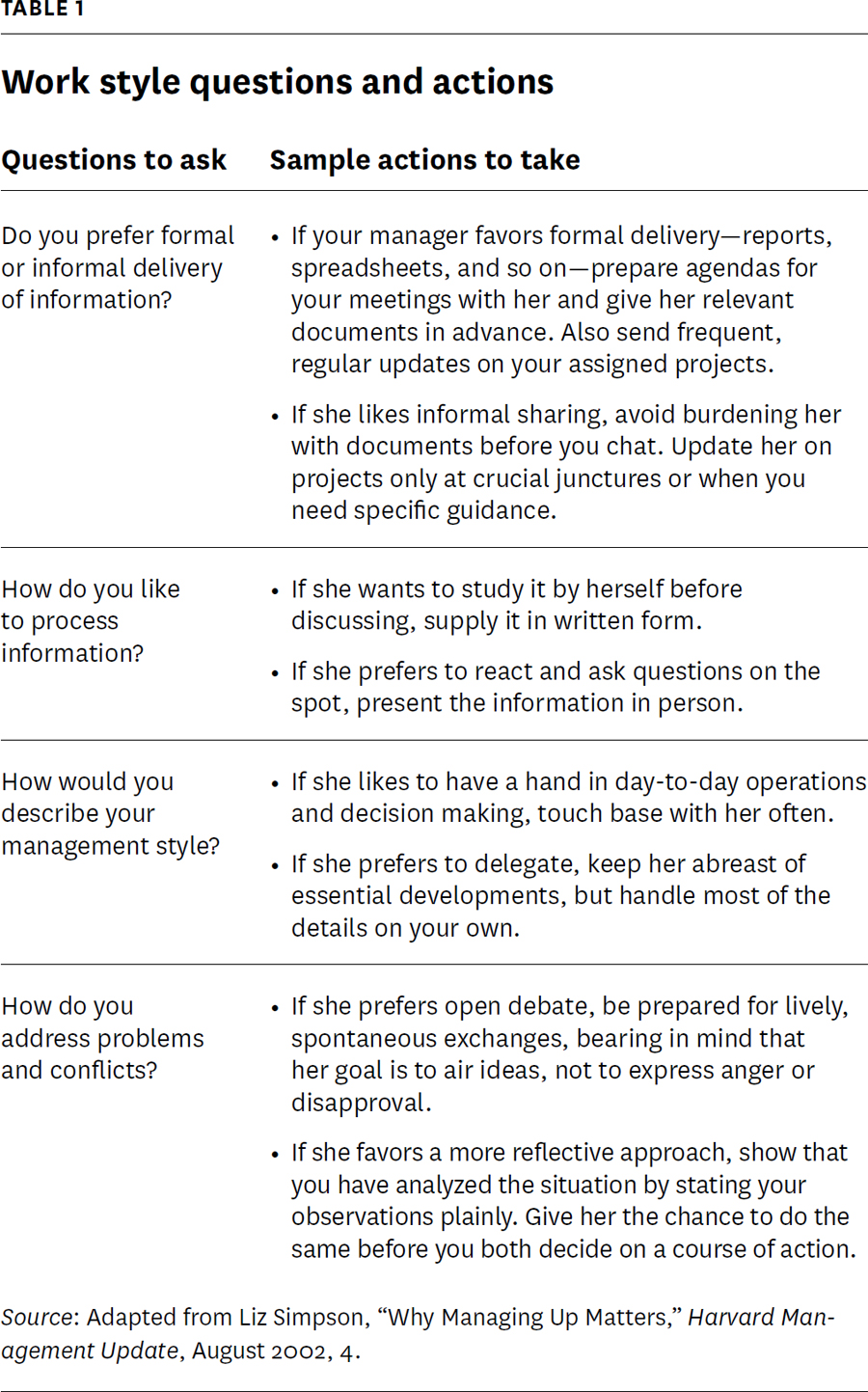

Your boss may not think to articulate her overall style or her day-to-day approach to getting things done, assuming they’re obvious. But chances are, she also won’t mind answering a few thoughtful questions about how she likes to work. Table 1 lists some questions you might try and related actions you can take. The fact that you’re asking demonstrates your interest in efficiency, your capacity for foresight, and your attentiveness as a direct report.

As presumptuous as it may seem, it’s also important to clarify your own work style with your manager in the interest of practicality and transparency. But don’t forget the power difference discussed earlier: Show a willingness to modify your own approach to arrive at a mutually suitable style of interaction with your boss. In leading by example, you may find that your manager extends the accommodation in the other direction, adjusting her practices a bit to suit what matters most to you.

At every employee’s core, from entry-level worker to CEO, are the things that drive her to do good work. Identifying what motivates your boss is a key component of managing up.

Sometimes it’s easy. For example, if your manager is driven by a desire to trim costs, she has probably shared that publicly. You might support that aim by streamlining redundancies in processes or systems that you oversee.

But some motivators run deeper. Perhaps your manager is a “big picture” person, inspired by vision, and prefers to leave details to team members like you. In that case, don’t dive into minutiae when you give her updates; briefly sum up what you’ve done and explicitly state how it supports her overall goals. By contrast, if your manager craves specifics, you might choose an illustrative example as a cross-section of your work. You’ll engage her with the intricacy of what you’re doing rather than boring her with the broad spectrum of your tasks.

Similarly, during check-ins with your manager, talk about what motivates you. That equips her to make engaging assignments and connect you with people in her network who will inspire you. Report back to your manager when you find a specific project exciting—make it easy for her to give you the kind of work that makes you tick.