chapter 6

Flip Your Perspective

So, I’ve made it to “the inner sanctum”—my first management team meeting. I always wondered what it was like in here. Before, my friends and I only speculated about what went on in these meetings. Now, I get to see what it’s really like.

It’s nothing like what we thought.

I’ve only been here for five minutes, and I’m in way over my head. All the managers are talking about lack of resources, needing more people. And a lot of their suggestions sound like they are at my expense. Are they trying to steal some of my people? Steal some of my budget? It’s my first meeting for goodness sakes.

I need to stop this. I must talk about my group and what I need. That’s how things get done around here, right? But that sounds so selfish. How do I do that so I don’t piss other people off? That’s not the impression I wanted to leave in my very first management team meeting. Does it have to be “I win and you lose?”

Later in the agenda, we will discuss a long-term strategy for our entire department. How do we communicate better to the entire organization and effectively work across boundaries to show how important our group and department are?

Who am I to say? I just got here!

I’m out of my league. What am I supposed to do?

Being Politically Savvy Is Not a Bad Reputation to Have

My first management team meeting was something I’d much rather forget than remember. I was the newbie. All the other managers had been managing their groups for years and had way more experience. One was actually my boss years ago. I felt like I didn’t belong. It showed.

They talked about their teams, which after a few weeks in my new role, I felt I could do too. But they also discussed resources, stakeholders, strategy. They each had a desire to portray how their specific team was an integral part of the organization. I had a completely new team and no clue how we fit in with the strategy of our department or our organization, or how we work with different stakeholders to bring value across the organization. These were all examples of the type of perspective that was considerably different, bigger, and unlike anything I’ve ever had to think about before. It can be unnerving for any new leader.

In this chapter, you learn what that meeting made all too clear to me. I had to flip my perspective. You do too. Most individual contributors have a narrow view of what goes on in their organizations. Now that you’re a new leader, flip your perspective. What does that mean? See things more broadly. Expand your vantage point. And realize that politics exists!

If you don’t flip your script by flipping your perspective, and account for the politics in your organization, what will people say about you? Things similar to what was said about these new leaders:

He needs to broaden and increase his degree of influence over projects and people (including those he does not formally manage) by developing win–win solutions. He needs to think a couple of steps ahead, and gain buy-in from stakeholders. . . . He should become more active in the broader corporate community so he can better understand the needs and perspectives of colleagues in other areas, especially those senior to him. Then, he can meet their needs and better influence decisions across the organization. . . . He doesn’t build consensus outside of his group to move larger ideas forward. . . . The internal relationships of this organization are not what she is used to. She has years of service but is considered an outsider to some of the management staff. Not fostering personal relations with peers has really worked against her.

As you flip your script by flipping your perspective and you start to take on that bigger view, you’ll quickly see the organizational politics at play. Your ability to flip your perspective has a bearing on how well you manage politics, how well you work with coworkers and stakeholders (up and down as well as across the organization), how you feel about your organization, and how well you do your job. Crummy politics have grave consequences, but embracing that perspective is not your only choice. You can flip your perspective, prosper in your organization, and be the boss everyone wants to work for.

Why You Should Flip Your Perspective

Many new leaders have a certain perspective on politics, for example, fulfilling their own agenda or working on projects personally satisfying to them. They want resources just for themselves at the expense of others. They are blind or closed-minded when it comes to understanding how others feel, how others can be helped, or how to share resources. For many new leaders, that win–lose mentality is there from the start. Why? It’s that old breakup line again, “It’s not you; it’s me.” They must win, or refuse to lose, because frankly that’s all they have ever known. It may even be the way they see their own leaders act.

For many, politics is a necessary evil or a game to play. Favoritism, bullying, power struggles, and self-interest abound. These individuals see people making others feel small, stealing credit, or passing off the work of others as their own to get attention, glory, power, or resources. And bending or blatantly breaking rules and manipulating the system or people to get what they personally want. It’s Frank Underwood in House of Cards.

Many new leaders don’t like seeing things this way and feel bad for succumbing to this view of organizational politics. They see politics as an unfortunate reality that can’t be avoided. It’s very discouraging, often demoralizing. They can’t comprehend how this perspective can be flipped. Just look at the word politics:

Poli—from the Latin, meaning “many.”

Tics—a bunch of blood-sucking insects.

That’s taken from Gerald Ferris and Pamela Perrewé, who have been studying politics for more than three decades. Their research1 portrays a grim picture. If you only see people going along to get ahead, cutting corners to get what they want, being rewarded for behaviors not formally endorsed by the organization, forming cliques to gain personal power, and/or the “favorites” being rewarded with higher pay and promotions, you’ll sense that the environment is rather threatening and unpredictable. You’ll feel less in control and won’t understand what should and shouldn’t be rewarded. The ambiguity can be confusing, upsetting, maybe even debilitating as Perrewé and her colleagues’ research shows; when politics is viewed in this manner:

• The health of workers is negatively affected.

• Conflict, stress, strain, tension, fatigue, and anxiety all increase.

• Feelings of helplessness, victimization, and burnout all increase.

• Performance at work is negatively affected.

• People want to leave their organizations.2

For one-third of the new leaders I studied in my research, managing internal stakeholders and politics was a current challenge. Of all the challenges, it ranked fourth. Consider the words of a woman in the nonprofit sector, who said:

[There is a] new focus on quality and speed, but peers are resistant. They find comfort in the old way of doing things. Unlike my peers, the new focus on quality and speed excites me, and I want to move faster than those around me. This causes friction, and I don’t know how to acknowledge their concerns and yet still get them to move faster.

Or this woman in the financial services sector, stuck with managing up:

My first line supervisor and second line supervisor have two very different (often opposing) leadership styles. One is “full speed ahead,” and the other is “proceed with caution.” The challenge is managing messages to both of them, since they often have opposing views. My first line supervisor may direct work; the second line disagrees with the direction. It’s a difficult place.

Unfortunately, managing politics won’t go away, and you will continually face it as you progress in your career. I once led a study3 asking 763 leaders from China, Hong Kong, Egypt, India, Singapore, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States the following question: “What are the three most critical leadership challenges you are currently facing?” These were all well-seasoned leaders with years of management experience, mostly in middle to upper middle or executive levels of management all over the world. They clearly knew how to lead others. Yet, struggling with managing internal stakeholders and politics was as relevant a challenge for them as it is for new leaders.

Organizational politics will not go away. You may not like to deal with politics. You may despise it, may even feel trapped by it and feel there’s just no other way but to act like everyone else.

No one blames you for feeling that way. But there is an alternative.

Those who flip their perspective see politics differently. This is not to say that they are naïve. They understand that there are competing interests, scarce resources, ambiguity, unclear rules and regulations, and a lack of information. They see it all.

The difference? They don’t let those perceptions get in the way of their goal to bring transparency and clarity to their teams, their coworkers, or stakeholders they work with. They remove uncertainty in the environment.

When you flip your perspective, you no longer cut corners, play favorites, or work the system to get things for yourself at the expense of others. You don’t perpetuate the self-serving behaviors and ambiguity that fill organizations. “I have to be right all the time” is not part of your vocabulary.

Politics is not a game to be played, where you have to win and everyone else loses. In fact, it’s not negative or positive. Politics is simply the air we breathe in organizations. When you flip your perspective in this way, you’ll survive—even thrive—at navigating politics in your organization with your political savvy, and feel good about yourself and the way you do it too.

You are not stuck with just one view of politics. When you flip your perspective and see politics differently, you’ll do what the boss everyone wants to work with would do: remove uncertainty and bring transparency, clarity, and a shared meaning to those you work with, so everyone knows what to expect by using your political savvy.

Ferris and his colleagues describe political savvy4 in ways I also see in my research and training of new leaders.5

• Understand yourself and the environment around you.

• Use that knowledge to be flexible and versatile enough to obtain goals that benefit you and others.

• Act in a sincere and authentic way.

That doesn’t sound bad, does it? Being politically savvy does not mean someone else must lose for you to win. It’s not about selfishness, having a façade, being a chameleon, or inauthenticity. Instead, it involves the sincere use of your skills, behaviors, and qualities to remove uncertainty and obtain goals that benefit you and others at the same time.

Being politically savvy is a must in modern organizations and in fact relates to many positive consequences. Across 130 studies, Ferris and others6 found that politically savvy people tend to

• feel more satisfied with their job;

• experience more commitment to their organization;

• be more productive with their work;

• go above and beyond what is outlined with their work; and

• have better career success and prospects for their future.

My own research shows the benefits of political savvy. Over the years, we continuously find that managers with political savvy are seen as better leaders, more promotable, and less likely to derail in their careers according to their boss, peers, and direct reports.7 So don’t think of political savvy as being a brownnoser, a backstabber, a backroom dealer, a schmoozer, a shark, or a snake. It’s not embarrassing, patronizing, or inauthentic. And it’s not being part of the “old boys network” either; Jean Leslie and I have found that women rate themselves just as high in political savvy as men do, and the positive relationship between political savvy and performance is the same for both men and women.8 There are no meaningful gender differences.

Having political savvy is a good quality that benefits you, your coworkers, and stakeholders in your organization. So, flip your perspective.

What You Can Do to Flip Your Perspective

Here’s the skinny: Understand what you want, what others want, and determine where there is common ground so everyone wins and benefits. To do that, you need political savvy. According to Ferris and his colleagues, and my own work and research, there are four different aspects of political savvy that you can develop.

1. Read the situation. Objectively scan, observe, and gather information about yourself and the people and the environment around you. Academics call this “social astuteness.” You are highly self-aware with your own thoughts and behaviors. You also thoroughly understand the thoughts, behaviors, and needs of coworkers and stakeholders you interact with.

2. Determine the appropriate behavior before acting. Based on observations of what is going on around them, politically savvy bosses learn what to do in a given situation. Find common ground and do what needs to be done, so everyone wins something and feels good about the final result. You don’t manipulate others to get what you want. Instead, work through the system to ensure everyone’s needs are served.

Determining the appropriate behavior also means you don’t come unglued in times of crisis either. You don’t lose your cool. It’s about impulse control and remaining calm in the storm that is around you. It’s thinking before you speak and act.

Many of us have told an inappropriate joke, shared information publicly that should have been kept private, acted without a care in the world, or became a volcano when mistakes were made. Some of us realized later we shouldn’t have done those things; we lived to tell about it and learned from our mistakes. Others, however, are no longer around because of that lack of impulse control and inability to think before speaking. They lacked political savvy. It’s the type of thing many people don’t come back from. Truthfully, it almost set back my own career. Here’s that story.

I was in the middle of training a leadership development program at CCL. A high-ranking official, whom I knew rather well and considered just as much a friend as a superior in my organization, needed a status update on a project, inquired about my schedule for an upcoming meeting, and asked if I could be part of that meeting’s agenda. So, during a break I quickly wrote an email saying I was currently in a program training about 25 leaders, could only attend a portion of the meeting next week, and that I couldn’t put anything together given the short notice. To close the email, I wrote down a couple of problems our project encountered.

I thought I was being attentive to her needs. For me, it was less about the content of the email and how it was worded, and more about the action of sending an email quickly to show that I was attentive to her needs of wanting information.

The way my superior read that email was much different. A couple of weeks later, she gave me feedback on what she read. The two major lessons I learned:

1. The email was blunt, terse, and discourteous. I needed to layer some context around the email. I was in a program but should have let the reader know I’d give what I could now and would provide more detail later.

2. Second, I gave problems, not possible solutions. In the leadership role I have, I can’t just say what’s wrong. I need to broaden my perspective; identify concerns and come up with possible solutions.

Looking back, I should have taken a little more time and not have been so abrupt. Moreover, I needed to flip my perspective. If I give problems, I should offer solutions too. Or given the context (not having enough time to give a detailed email because I was in the middle of training a program), I should have said that we could talk about coming up with solutions later.

We all have probably made a mistake of not thinking before speaking and have acted on an impulse. But you can avoid it with your political savvy.

3. Network strategically. This is not about having the most friends on Facebook, the most connections on LinkedIn, or the most followers on Twitter (by the way, follow me on Twitter @Lead_Better). It’s not about going to conferences, joining social, professional, or civic groups and collecting a stack of business cards. Networking strategically is building strategic relationships and garnering support for your goals and those of your coworkers and stakeholders. By connecting with influential individuals who hold different resources and valuable assets, you’ll gain a voice where you might not have been heard otherwise. More importantly, you could gain access to important information from key insiders.

So what does a strategic network look like? ODD: open, diverse, and deep. Through their research, that’s how Phil Willburn and Kristin Cullen-Lester at CCL9 describe the networks of successful leaders.

Open—The people you know in your network should not all know each other (that’s a closed network). When you have an open network, the people you know are connected with other people that you don’t know. With this open network, you’ll likely hear new information you never would have before, gather different ideas and perspectives, and capitalize on that information to influence others or make well-informed decisions that benefit all parties involved.

Diverse—Those in your network should not all be from the same group or division (that’s a homogeneous network). In a diverse network, the people in your network should be from different groups and divisions and should cross several different boundaries, including up, down, and across the formal hierarchy, as well as those that span functional or geographic boundaries. When your network can span these boundaries, you can build bridges so that all involved feel part of the solution.

Deep—What you know about the people in your network isn’t just their name, title, and where they sit (that’s a shallow network). It goes deeper than that. Knowing where they went to school, what team they root for on the weekends, what their pet’s name is, or what their kid did to win the talent show is a good start. But it goes deeper still. Get to know these people: understand what they do, the situations they are in, and their motives, values, and needs.

4. Leave people with a good impression. Many of us who study political savvy believe what Ferris suggests: if you have political savvy, you appear not to have it. Everything you do—your behaviors, your actions, the words you say—are all genuine, transparent, and authentic. As a boss with political savvy, be sincere and authentic in all that you say and do, and leave people with a good impression.

Think about the politically savvy attributes. If you read the situation in a sincere and authentic way, you will be described as “astute” or “ingenious” or “clever.” But if you do it in an inauthentic way, you’ll probably be labeled as “cunning” or “sly” by others. Determine your appropriate behavior in a sincere and authentic way, and you’ll be seen as “flexible” and “adaptable.” If not, you may be regarded as “cold” and “calculated” or possibly “Machiavellian” in nature. Network strategically in a sincere and authentic way, and you are a “relationship builder,” but if not, you’re branded a “brownnoser” and “power hungry.” Which adjectives would you want attached to you?

Think about leaders without political savvy, those who haven’t flipped their script. You know those people. They are seen as manipulative and selfish. They are like snakes in the grass (or maybe snakes on a plane, for Samuel L. Jackson fans). They say one thing, shake your hand, and stab you in the back later.

Do you want to manipulate someone to do something? Probably not. Even thinking about that probably feels disingenuous. But do you wish to sincerely and authentically influence someone to get what you and others need? That’s when you know you’ve flipped your script by flipping your perspective. Leave people with a good impression by being sincere, trustworthy, and genuine. You’ll build trust and confidence with those you work with now and in the future.

For some of us, this may be difficult. Maybe you’ve gotten some feedback that people see you as self-serving and manipulative. Maybe you’re afraid there’s just no other way. Well, fear no more. Ferris, Perrewé, and their colleagues believe that although political savvy is somewhat innate, it can be trained, developed, and enhanced in new and experienced leaders alike. I believe it too, as I continually help new leaders become aware of political savvy and, in programs and workshops, help them develop it.

Make it a point to flip your perspective. You can do it! It’s not how to manipulate people to achieve an outcome. Flip it. Choose to behave genuinely, and exhibit sincerity and trustworthiness to reach a goal all parties want. You have the potential to be considered a well-respected, politically savvy boss in your organization.

Two Ways to Flip Your Perspective

Up to this point, you’ve read how important it is to flip your script, shining the spotlight less on yourself and more on the people you lead and serve: “It’s not about me anymore.” As you flip your script by flipping your perspective, shine the spotlight in many different directions to many different stakeholders inside and outside the organization. As you do, your political savvy will help you deal with two of the topics I frequently hear about when I work with and train new leaders: “How do I manage up?” and “How do I manage in a matrix?”

Manage up. For many, “managing up” leaves a bad taste in their mouths. They think of it as self-promotion, kissing ass, brownnosing, pandering, bowing down, sucking up, not leaning in, or selling out. When you flip your script, you see it differently.

First, don’t think of it as managing your boss, superiors, and the like. Think of it as helping your senior colleagues. Managing your boss sounds like you are trying to get your boss under control. Helping your senior colleagues is less formal and stuffy, shows respect, and sounds less manipulating.

Second, think of helping your senior colleagues as part of your job. Take responsibility of the relationship and be proactive. It’s your job to seek out, understand, and influence your senior colleagues, not their job to find you, tell you what they think, and agree with what you want. If you have political savvy, you inform your senior colleagues about what is going on. You keep them in the loop. You’re busy, and so are your senior colleagues. So, be proactive in keeping your senior colleagues informed because they can’t know everything happening with your team.

It’s not brownnosing. Think of it this way: if you were in their shoes, what should they know about you and your team? That’s keeping your senior colleagues informed. They’ll be able to communicate that information up and across the organization.

The Matrix is not just a movie. Quick story:

About two months into my role as director, I was in a difficult situation. I have an employee who reports to me, but the person isn’t in headquarters and frequently must respond to the needs of that location. So, I’m a boss who doesn’t have complete authority over the person. It’s very hard to get the person focused on work because many times this individual doesn’t know what to do and asks, “Should I focus on what you tell me or what the people in my location tell me?” And because role clarity is so important in leading teams, I knew I needed to give that to my direct report. But how, given the reporting relationship?

I went to my VP for help. Her response?

“Welcome to the matrix.”

Contemporary organizations are more complex than the hierarchies that structured them in the past. Some of our reporting relationships are in the matrix—we report to our department and a functional manager. Matrixed relationships are hard to manage. But not impossible. Find what makes your stakeholders tick. Listen to what they’re telling you. Find the common ground. This is how I dealt with the situation:

My direct report, my boss, my VP, and a senior colleague from the location in which my direct report works, all had a conference call.

It was 10:00 P.M. my time, an hour in, and I was struggling, frustrated, and sleepy. All I heard was “Do you realize what we are up against?” and “Do you know the things we are trying to do?”

By listening to the pressure points and needs of my senior colleagues, I found the common ground that would help everyone on the call. On the spot, I said something directed to the senior colleague at the other location.

“I truly sympathize with all that is occurring. I have a better understanding of the work you are doing and understand you are targeting a certain population. So, how can we in research help you with your strategy? Can we think of ways to do our research and target the population you feel is most important to you and your business?

My VP IM’d me immediately and gave me a great vote of confidence, saying, “Great reframe.” That’s when I knew I’d done something cool. Around 10:45 P.M. my time, it felt like everybody had won. To be clear, I have no direct authority over my senior colleagues (just the opposite). But because I expanded my perspective and looked at things through their eyes, my political savvy enabled me, from my less senior position, to align our work to the other location. And my direct report feels more engaged in the work. Everyone wins.

Coming Full Circle

I have come a long way since that first management team meeting. Granted, I sometimes feel like an imposter in those meetings. But I am growing more comfortable in my role. In fact, I remember the exact moment I felt like I sort of belonged. My mindchatter before the meeting went something like this:

Another team meeting, the usual suspects—don’t look like an idiot! Actually, you won’t. You’ll do great.

First thing on the agenda, we are talking about development planning of those working in our department. You will make sure to speak up for the people that report to you. Plus, show how increasing their effectiveness can directly help the other groups in our department too. This will show you genuinely care not just for your people, but for your peers and their people as well.

Second on the agenda is our own team development. From our own internal opinion surveys, we on the management team know that we are falling short in some areas. People don’t feel connected to each other. Ask your peers how we together can get our people to feel more connected. They have been in the organization and in their management role longer than you. So what have they seen or heard in the past that has been effective in getting people to feel more connected?

Final item on the agenda: How can our groups get better at internal messaging, at making clear to our stakeholders across the organization what we do and why it’s important. So try to understand our stakeholders’ point of view. How is our work important to them to get their work done? What would they need from us that could help right now?

Later that evening, I went out to a business dinner with some of my peers from that meeting. Upon leaving the restaurant, two of my peers praised the way I handled myself in that morning’s meeting. I asked them for clarity and feedback, what exactly it was that I did. Each told me I expanded my perspective. I also thought of things from their own perspective and from our stakeholders’ perspective too. That kind of thinking was needed in our group.

I truly felt like I flipped my perspective. I was looking out for my team, working well with my peers, and helping my senior colleagues. Without my political savvy, none of that would have been possible.

I felt great driving home that night, just like I did when I first got my promotion months ago.

Then a rhetorical question hit me:

Why did you flip your perspective? In fact, why did you flip your mindset, skill set, relationships, your “do-it-all” attitude—any of it? Do you truly have a desire to help the people that report to you? Do you really want your colleagues to succeed? Or are you doing these things for your own personal gain?

Like me, you have a choice to make. Will you lead from your own personal agenda? Does it matter what you do, so long as the ends justify the means, or the means justify the ends? Or will you be aware at all times that your actions and decisions can affect others, whether you know it or not?

Flipping your focus is the final act, probably the toughest in flipping your script. It’s the one that takes the most amount of soul searching. One with the highest stakes that can affect more than just you and the people you lead and serve. It may sound ominous, but it can be addressed, as you’ll read in the next chapter.

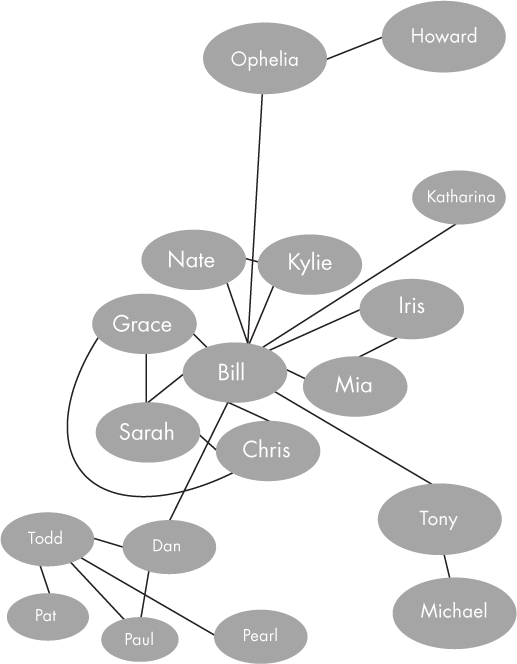

An example of a network map.