chapter 8

Conflict and Project Management

Madness is the exception in individuals but the rule in groups.

Nietzsche

Project managers face conflict as part of their daily life from a number of sources, internal and external, and in dealing with other project stakeholders [1, 2, 3]. One study estimated that the average manager spends over 20 percent of his or her time dealing with conflict [4]. Project managers would likely suggest that the 20 percent figure understates the case! Conflict is often an offshoot of power struggles and political dynamics with an organization. Because so much of a project manager's time is taken up with active conflict and its aftermath, it is important to examine this process within the project management context.

In the past, much has been written about the sources of conflict within the project management context. Little, however, is known or understood about the actual dynamics of the conflict process itself. That is, once a conflict occurs, what are some of the common responses and actions that are fairly predictable? This chapter explores the process of conflict, examines the various sources of conflict for project teams and managers, develops a model of conflict behavior, and fosters an understanding of some of the most common methods for de-escalating conflict. Many conflicts develop out of a basic lack of or unwillingness to understand another party's position. And once a conflict does occur, either within or outside the project team, project managers who are aware of the various action alternatives they can employ have a real opportunity to not only defuse conflict but also to learn valuable lessons from the episode. Understanding these issues well will improve project managers’ use of power, make them better at their job, reduce stress, and enhance the team environment.

What is Conflict?

One of the best definitions of conflict suggests it is the process that begins when one perceives that one or more others have frustrated or are about to frustrate a major concern of theirs [5, 6]. There are two important elements in this definition. First, it suggests that conflict is not a “state” per se, but a process. As such, it contains a very important dynamic aspect: conflicts evolve [2]. Further, the one-time causes of a conflict may change over time; that is, the reasons why a conflict started between two individuals or groups may no longer be valid. However, because the conflict state is dynamic and evolving, once a conflict has occurred, the reasons behind it may no longer matter.

Second, conflict is perceptual in nature. It does not ultimately matter whether or not one party has truly frustrated another party. The key is that one party perceives that state or event to have occurred. That perception is enough because, for the first party, perception of frustration defines their reality.

Sources of Conflict

There are an enormous number of potential sources for conflict. Some of the most common include competition for scarce resources, violations of group or organizational norms, disagreements over goals or the means to achieve those goals, personal slights and threats to job security, long-held biases and prejudices, and so forth. Many of the sources of conflict arise from the positions of managers or the nature of the work they do. Another equally compelling set of causes also stem from the individuals themselves; that is, their own psychological processes contribute to the level and amount of conflict within an organization. One useful method of looking at the causes of conflict is to separate the organizational and interpersonal causes of conflict.

Organizational Sources of Conflict

Some of the most common organizational causes of conflict include:

- Reward systems

- Scarce resources

- Uncertainty over lines of authority

- Differentiation.

Reward systems are often a source of conflict because, in some organizations, there are in place competitive reward systems that pit one group or functional department against another. When functional managers, for example, are evaluated on the performance of their subordinates, they are loath to allow their best workers to become involved in project work for any length of time. The organization may have unwittingly created a situation where functional managers perceive that either the project teams or the departments, but not both, will be rewarded for superior performance. In such cases, they will naturally retain their best people for functional duties and offer less-desirable subordinates for project team work. The project managers, on the other hand, will also perceive a competition between their projects and the functional departments and develop a strong sense of animosity toward functional managers who they perceive, with some justification, are putting their interests above the organization.

By its very nature, a project generates significant differences of opinion in how scarce resources, particularly personnel and money, are used. Project managers face an on-going battle with functional managers to get the resources needed for a successful project. This easily leads to confrontation not only between project managers and department heads, but also between the functional managers who know one or more of them will lose resources.

Uncertainty over lines of authority asks the tongue-in-cheek question, “Who's in charge around here?” In the project environment, it is easy to see how this problem can be exacerbated due to the ambiguity that exists in terms of formal channels of authority. Project managers and their teams sit “outside” the formal organizational hierarchy in many organizations. As a result, they find themselves in a uniquely fragile position of having a great deal of autonomy but also responsibility to the functional department heads who provide the personnel for the team. When a project team member from R&D, for example, is given orders by a functional manager that subsume or directly contradict directives from the project manager, the team member is placed in the dilemma of finding, if possible, a middle ground between two authority figures. In many cases, project managers do not have the authority to prepare performance evaluations of team members, that control is kept within the functional department. In such situations, the team member from R&D, facing role conflict brought on by this uncertainty over lines of authority, will most likely do the expedient thing and obey functional managers because of their “power of the performance appraisal.”

The final source of organizational conflict, differentiation, suggests that as individuals join an organization within some functional specialty, they begin to adopt the attitudes and outlook of that functional group. For example, when asked for an opinion of marketing, a member of the finance department might reply, “All they ever do is travel around and spend money. They're a bunch of cowboys who would give away the store if they had to.” Marketing's response would follow along the lines of, “Finance people are just a group of bean-counters who don't understand that the company is only as successful as it can sell its products. They're so hung up on their margins, they don't know what goes on in the real world.” Now the important point in each of these views is that, within their narrow frames of reference, they are both essentially correct. Marketing is interested primarily in making sales and finance is devoted to maintaining high margins. These opinions, however, are by no means completely true. Instead they reflect the underlying attitudes and prejudices of members of both functional departments. The more profound the differentiation within an organization, the greater the likelihood of individuals and groups dividing up into “us” versus “them” encampments, which continue to promote and provoke conflict.

Interpersonal Causes of Conflict

In addition to these organizational causes of conflict, consider also some of the salient interpersonal causes. While by no means a comprehensive list, among these interpersonal sources of conflict are:

- Faulty attributions

- Faulty communication

- Grudges and prejudices.

Faulty attributions refers to misconceptions of the reasons behind another's behavior. When people perceive their interests have been thwarted by another individual or group, they typically try to determine why the other party acted as they did. In making attributions about another's actions, we try to determine if their motives are based on personal malevolence, hidden agendas, and so forth. Often, groups and individuals will attribute motives to other's actions that are personally most convenient. When one member of a project team, for example, has his or her wishes frustrated, it is common to perceive the motives behind the other party's actions in terms of the most convenient causes. In other words, rather than acknowledge that reasonable people may differ in their opinions, the frustrated person may assume the other is provoking a conflict for personal reasons, “He just doesn't like me.” This attribution is convenient for an obvious and psychologically “safe” reason. If we assume the other person disagrees with us for valid reasons, it implies a flaw in our position. Many individuals do not have the ego-strength to acknowledge and accept objective disagreement, preferring to couch their frustration in personal terms.

A very common, interpersonal cause of conflict stems from faulty communication. This implies the potential for two mistakes: (1) communicating in ambiguous ways which leads to different interpretations, resulting in conflict, and (2) unintentionally communicating in ways that annoy or anger other parties. Lack of clarity sends out mixed signals: some will understand the message the sender intended to communicate, others will interpret it differently. Consequently, a project manager may be surprised and annoyed by a subordinate's work while the subordinate may genuinely think he or she is adhering to the project manager's desires. Likewise, project managers often engage in criticism hoping to correct and improve a project team members’ performance. Unfortunately, what the project manager may consider to be harmless, constructive criticism may come across as a destructive, unfair critique if the information is not communicated accurately and effectively.

Interpersonal conflict refers to the personal grudges and prejudices that each of us brings to any work situation. These attitudes arise as the result of long-term experiences or lessons taught at some point in the past. Often unconsciously held, we may be unaware we nurture these attitudes and may feel a genuine sense of affront when we are challenged or accused of holding biases. Nevertheless, these grudges or prejudices, whether they are held against another race, sex, or functional department, have a seriously debilitating effect on our ability to work with others in a purposeful team and can ruin any chance of project team cohesion and subsequent project performance.

Steps in the Conflict Process

Regardless of the triggering cause, once conflicts, either intra- or intergroup, have begun, they tend to follow a rather well-defined pattern. It is useful for project managers to be aware of this pattern because it serves as a template to recognize various conflict dynamics. If the nature of the conflict process is understood as it progresses, one is in a better position to search for methods to defuse and minimize the conflict or channel its energies into more constructive pastimes. In this section, we examine the stages in the conflict process and offer some suggestions for project managers on how to most effectively deal with the conflict dynamics that often emerge.

Typically, there are five recognizable stages in the conflict process:

- Frustration

- Conceptualization

- Orientation

- Interaction

- Outcome.

Frustration

The first stage of any conflict process is triggered by an event that sets one or more people at odds. As suggested in the original definition of conflict, this event is referred to as “perceived frustration.” Frustration comes in many forms and approaches. Earlier, we identified several sources of frustration, and classified them into two categories: organizational and interpersonal. The important point to remember is that frustrations occur in everyone's life on a daily basis. Therefore, there must be some reason why we respond to certain frustrations in a confrontational manner but not to others. Often, this choice is predicated on our perception of how important the issue is to us. Under normal circumstances, a traffic jam would be a source of frustration, but we would rarely deem it serious enough to actively confront the city administration over the issue. On the other hand, in situations that involve slights to status, promotion possibilities, or public image, we tend to react to frustrations more directly. It is these situations, where we attach a level of importance to the frustrated goal, when we are most likely to respond in an aggressive and competitive manner.

Conceptualization

Conceptualization means defining the issues underlying the source of conflict. Analyze why a conflict is occurring between ourselves and our team or with someone else, and an interesting psychological process begins to occur. We see the conflict through the lens of egocentricity. Egocentricity refers to the predilection of most people to define issues solely in terms of their own concerns. When confronted with a situation in which we feel frustrated by another individual, we respond in a way that does not recognize the other party's perspective. That is, we perceive the other person is thwarting us, without considering their point of view or why they are acting in a particular way.

The clear alternative to analyzing frustration in terms of egocentricity is to develop insight into the other party's concerns. Remember, never judge another person unless you have walked a mile in their shoes. Unless another person's motives, intent, and past experiences are understood, we cannot objectively address the nature of the conflict. Rather, we will continue to be inclined to respond with an egocentric approach that only further solidifies the lines that separate the rival parties’ positions. Attempting to gain this insight into the underlying issues involves refusing to capitulate to the initial sense of frustration with another party and search for reasons why that person or group is operating the way they are.

It is this search for the answer to “why” that will defuse many conflicts before they escalate. It requires the project manager or team member to be able to forego the appeals of egocentricity and to try and analyze the problem from the other party's perspective. Depending upon the nature and degree of conflict, this rational objectivity can be very difficult, but well worth the effort. If we halt conflicts at this stage, many of the problems that would continually plague the project team throughout the project can be avoided.

Orientation

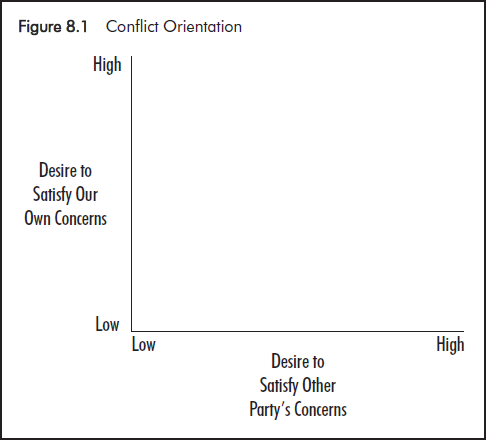

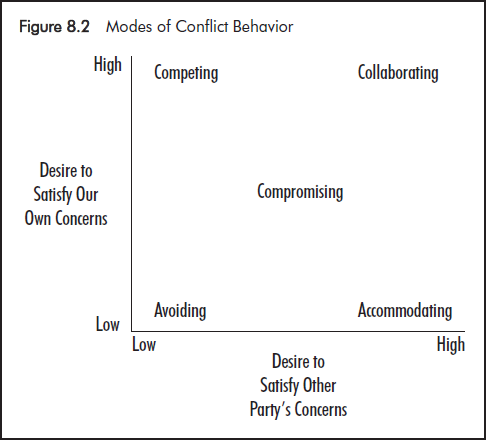

Orientation is the outlook we begin to adopt as a conflict episode continues to escalate. Thomas [5] and Ruble and Thomas [7] argue that conflict orientation generally involves operating along two separate dimensions of concern: (1) the degree to which one party seeks to satisfy their own concerns, and (2) the degree to which a party seeks to satisfy the other person's concerns. Figure 8.1 shows Ruble and Thomas’ [7] conceptualization of this two-dimensional model of conflict orientation. They argue we make implicit trade-offs in our willingness to seek our gains versus our willingness to satisfy the other party to the conflict. They further posit that the underlying motive driving these two dimensions is our desire to be assertive and gain maximum advantage while being cooperative with the other party in order to maintain satisfactory relationships [8].

Within this two-dimensional model of conflict orientation and behavior, Thomas suggests five distinct and recognizable types of conflict behavior are potentially possible:

- Competing

- Accommodating

- Avoiding

- Compromising, and

- Collaborating.

The decision of which type of behavior to engage in resides solely with the party who is conceptualizing the nature and reasons for the conflict. Figure 8.2 shows each of the five conflict-handling styles.

Competing behavior is basically assertive and uncooperative. Someone adopting a competing style has no regard for satisfying the other party's concerns, viewing conflict as a win-lose proposition in which they have resolved not to lose. Competing behavior is often used by insecure or power-hungry people who will use every technique and trick to get their way. It is often ironic to find that individuals who are high on the competing dimension have great difficulty in operating under any other style, no matter what the nature of the conflict. For example, highly competitive people take issues of resource allocation and the results of a game of gin rummy with the same degree of intensity. They cannot distinguish between “important” conflicts and “unimportant” conflicts; indeed, the very existence of a concept such as an “unimportant” conflict is alien to their way of thinking.

At the opposite extreme from competing behavior is the accommodating style. As Figure 8.2 shows, accommodators enter conflict from the perspective of seeking to first satisfy the other party's concerns. Accommodators foster nonassertive and cooperative styles, usually in an effort to be true “team players.” They are quick to look for ways to defuse a situation or to allow the other party to win. The accommodating style can be useful when the issue of concern is seen as more important for the other side than for the accommodator. It may serve as an important goodwill gesture or a basis for “storing up” favors the manager may need at a later point. If overused, however, the accommodating style tends to create passivity in a project manager, a state which can deprive subordinates or peers of useful viewpoints and contributions.

The avoiding style is one that is both unassertive and uncooperative. Individuals who rely on the avoiding style manifest no desire to either satisfy their concerns or the concerns of the other party to the conflict. Avoiding tends to be an effective method for sidestepping a conflict that one party does not seek. It is the style of organizational diplomats and politicians who perceive they can accomplish more if they operate behind the scenes rather than in the open, in conflict with another party.

Compromising behavior falls somewhere between assertive and cooperative behavior. It is a desire by one party to satisfy some of their concerns and a willingness to give in on other points. A compromiser sees conflict as a win-lose situation and believes that in order to get something it is necessary to give up something else. A compromising style tacitly acknowledges the importance of making concessions to gain something from the conflict. As a result, while compromisers see conflict in terms of winners and losers, they generally feel that each party can win a little and lose a little.

Collaborating behavior rates high on both assertiveness and cooperativeness. Collaborators view conflict from a very different perspective than most managers in that they reject the win-lose argument most of us believe underlies conflict. Always seeking a win-win solution, to achieve such an outcome, collaborators readily work with the other party to see if it is possible to find a solution that fully satisfies both sides. This sort of joint problem solving requires a great deal of flexibility, creativity, and precise communication between the parties in conflict.

A collaborating style is usually necessary when the issue at hand is too important to be solved with a compromising approach. In situations when project leaders are seeking to make major product specification changes or determine resource allocation, they may be faced with two or more distinct alternatives. Rather than vainly attempt to satisfy these disparate viewpoints by offering a compromise that will please no one and do nothing to further the development of the project, these managers may hold a series of project team meetings to get all positions on the table where they can be addressed in a problem-solving session. The result of this meeting may be a new strategic focus for the project with new tasks and responsibilities for each team member. In this meeting, the problem underlying the conflict could not be ignored. Further, allowing one team member to dominate the others with a competing style could potentially result in an incorrect decision. The best alternative for the project manager is to find, in collaboration with the project team, a solution that offers a win-win alternative.

Because no one conflict-handling style is appropriate in every situation, insightful project managers develop flexibility in their approaches to dealing with conflicts, either their own or those of team members within the group. The benefits of a collaborative style is that, unlike competing or avoiding, a collaborative style emphasizes group relationships. Using this style offers a method for enhancing communication and creative problem solving. In doing so, a collaborating approach can bring a team in conflict closer together, rather than driving them further apart by solidifying the conflict situation.

Interaction

Once a conflict episode escalates, a number of different exchanges begin to occur between the two parties in conflict. This exchange process is referred to as conflict interaction. While there are many actions conflicting parties can take during this process, our focus is on some of the more common dynamics of group conflict during this stage.

One common occurrence, usually early in the conflict, is reinforcement through stereotyping. When another party is frustrating a goal we value, we often respond by attributing their intransigence to convenient (and often incorrect) motives. For example, in a budgeting dispute with the project accountant, a project manager may react by saying, “What can you expect from a group of unimaginative bean-counters?” This reaction, while common, underscores the potential for reinforcing the disagreement by creating a self-serving stereotype of the other party. In this process, all opponents are selfish, willfully ignorant, or malicious because these attributions allow us to hold the high ground in the dispute.

Through stereotyping other professions, cultures, races, or the opposite sex, we create a cause for discontent without being forced to reexamine our motives as a potential contributor to the conflict. As the name of this process suggests, rather than attempting to defuse or suppress tension, the first inclination is to reinforce the conflict, making it that much more difficult to correct.

Another process likely during the interaction phase is one in which conflict begins to heighten feelings of positive identification with one's own group. There is a tendency, when we perceive a conflict with an external stakeholder, to close ranks and become more single-minded in our attitudes and dispositions. As a result of that process, it is common for groups to develop a superiority complex vis-à-vis the other group. This superiority complex feeds our inclinations to regard our position as sacrosanct and justified as opposed to the “devious” and “maliciously inclined” opponents.

On a national level, this positive identification dynamic occurs quite frequently. For instance: In the early 1980s, just prior to the Falkland War with Great Britain, Argentina was in a state of tremendous political turmoil. Crowds in Buenos Aires and other large cities continually protested the right-wing rule of the military junta that controlled the government, until Argentina invaded the Falklands, and created an external foe. Overnight, the crowds that had been demonstrating against the government became vast throngs supporting their leaders, united in their opposition to Great Britain. This is an example of the positive identification effect that occurs in the face of external conflict.

Another dynamic likely during the action phase is exaggerating the positive nature of our group and its members, and distorting and exaggerating differences between our group and the opponent. Once we find ourselves in a conflict situation, there is pressure to conform to group norms, swallow internal differences, and deny any degree of similarity with the opposing group. This separation solidifies differences, making it harder for the groups to seek common ground. In fact, we actively avoid the potential for identifying commonalties, preferring to focus on the differences and the reasons that justify our beliefs.

Outcome

The final stage of the conflict process is the outcome, two parties reaching an agreement, resolving the conflict. It is important to realize, however, no matter what the outcome—full agreement, or a tacit understanding—there will be residual emotions and ill will from the process. Individuals do not forgive and immediately forget conflict episodes, particularly if the issues were significant or the emotional commitment brought the conflict to a personal level. Project managers must be cognizant of the likely detritus of conflict. Playing down or smoothing over a problem when it has been “resolved” may be overly simplistic and ignores the potential for further tensions.

A final point about the outcome: Realizing the difference between short-term and long-term outcomes. Understand the truth in the phase, “Win the battle and lose the war.” When a manager wins a conflict, there is a potential that the other party will remember the experience and look for retribution opportunities. This is particularly true in the case of a manager who is prone to rely solely on a competing style in dealing with conflicts. A competing approach, based on assertiveness and lack of concern for the other party, is likely to create bad feelings on the part of the other party. Whether that party wins or loses the conflict, they are likely to remember the event and seek ways to repay the other group [9].

Table 8.1Methods for Resolving Conflict

Avoidance

- Non-attention

- Physical separation

- Limited interaction

- Forced interaction

Defusion

- Smoothing

- Compromise

Confrontation

- Problem-solving

Methods for Resolving Conflict

A number of methods for resolving inter- and intra-group conflict are at the project manager's disposal. Before a decision is made about what approach will be employed, it is paramount for project managers to consider a number of relevant issues [10]. For example, will siding with one party to the dispute alienate the other party? Is the conflict professional or personal in nature? Does any sort of intervention have to occur or can team members resolve the issue on their own? Does the project manager have the time and inclination to mediate the dispute? All of these questions play a role in determining how to approach a conflict situation. Project managers need to learn to develop flexibility in dealing with conflict, assessing and prioritizing situations in which it is appropriate to intervene and those in which the sounder course is to adopt a neutral style.

As Table 8.1 illustrates, it is helpful to categorize possible conflict resolution methods into three fundamental philosophies: avoidance, defusion, and confrontation. Each approach has its benefits and drawbacks and, more importantly, each may be an appropriate response under certain circumstances.

Avoidance

Avoidance techniques suggest that the project manager ignore the causes of the conflict and allow it to continue under controlled circumstances. Avoidance is a conflict-handling approach that requires the project manager to adopt a position of neutrality and passivity, while the parties to the conflict work out their differences. An example of avoidance is non-attention—the project manager simply looks the other way and allows the parties in conflict to come to their own resolution without stepping in. Mark McCormack [11], in his entertaining work What They Still Don't Teach You At Harvard Business School, points to a situation in which two of his vice presidents had developed an antagonism based on personal dislike, not professional reasons. He states that when conflict is of a personal and emotionally charged nature, a prudent manager will often refuse to intervene, sending signals that this sort of interaction is unacceptable, but otherwise expecting the warring parties to work out their differences.

Other types of avoidance techniques are physical separation, limited interaction, and forced interaction. These approaches are similar in requiring project managers with subordinates in conflict to find ways to keep those involved out of each other's way. When they must be together, the project team leader plays the role of referee, making sure that the conflict is kept at bay for the course of the meeting.

An alternative to limited interaction may be its exact opposite: forced interaction. In this scenario, the project manager gives two subordinates a task which requires them to work harmoniously or both will end up looking equally guilty. As a result, they are forced to lay aside their differences and cooperate for the sake of the project, for which each held joint responsibility.

In each of these techniques, rather than refraining from seeking the source of conflict, the project manager pays attention to ensuring the fallout from subordinate conflict does not impact on the project's development. This may be in vein, however, as frequent or intense conflict can force team members to expend tremendous amounts of energy on worthless pursuits. A decision to adopt an avoidance tactic in the face of subordinate conflict should be made with due consideration of the implications of allowing the conflict to continue.

Defusion

Defusion techniques are an attempt to buy time until both parties have a chance to cool down and deal with the conflict in a more “rational” manner. As in the case of avoidance techniques, defusion approaches do not seek the underlying causes of the conflict. They are intended to address the unintended consequences once a conflict situation exists. One defusion technique is referred to as smoothing, which involves the project manager playing down group differences and emphasizing commonalties. Using this approach, a project manager might say, “Come on, people. We are all on the same side here. Let's get together to work on the project.” Smoothing represents appeals to professionalism or to the group's commitment to higher goals (the organization, the project, etc.).

A second defusion technique is compromise. Compromise refers to the implicit assumption that for one party to the conflict to win on some points they must be willing to give up others. The compromise approach is classic “give and take” management, and as with smoothing, does not require the project manager to plumb the root causes of the conflict. It arbitrates the process once it is under way.

Confrontation

The final conflict-resolution method is confrontation, best represented by problem-solving meetings. Unlike the other two sets of conflict resolution methods, confrontation requires project managers to seek and expose the causes underlying the conflict. Each source, personal, professional, or both, is identified and discussed at length, so that parties to the conflict have the opportunity to put issues out on the table where they can be addressed and resolved. Problem-solving meetings are difficult, requiring a project manager to have patience, nerves, and poise. When a manager seeks the causes of a conflict, it is akin to attempting to understand the other individuals’ underlying motives and goals. Frequently, the parties involved are hesitant to open themselves up and examine basic beliefs and biases. Hence, the problem-solving process is often lengthy, accompanied by high emotions, intransigence, and obstructions from the parties concerned. Problem-solving meetings are often necessary for future project team operations, but contain an element of risk. If the meeting is not handled well, it can solidify conflict and ill will between group members, making future cooperative activities more difficult.

Summary

In attempting to resolve conflict, each of the approaches outlined may be appropriate in different situations. A problem-solving session is not always beneficial or warranted, nor is it fair to say non-attention is always “lazy” management. Project managers must learn to understand their own preferences when it comes to handling conflict. Once a greater sense of self-awareness about our own predilections is achieved, we will be in a far better position to resolve our own conflicts constructively and deal more effectively with subordinate conflicts. The key is flexibility. It is important not to lock into any particular conflict style nor favor one resolution tactic to the exclusion of all others. Each have strengths and drawbacks that the project manager should know as part of his toolkit.

Many noted writers on project management have pointed to the inevitability of conflict in the project development process [12, 13]. Conflict comes from a variety of sources and for a myriad of reasons. It is essentially impossible for a project manager to run a team and develop a project without having to confront a number of conflicts along the way. In this chapter, we developed a framework for the organizational conflict process, examined some common causes of conflict and argued that the unique nature of project-based work makes it a natural environment in which conflicts will develop. We outlined a model of the conflict process and showed that when project managers understand the common steps, they are in a better position to defuse the conflict or use it constructively to further the project's goals. Conflict has potential to delay and even kill a project unless managers learn how to recognize its characteristics and harness the energy appropriately. Conflict is inevitable, it is not disastrous. The degree to which a conflict disrupts a project's development depends upon the project manager's willingness to learn enough about conflict to deal with it effectively.