chapter 1

Project Management and the Problem of Politics

Tim Robinson has a problem. Sitting at his desk after yet another in a seemingly endless round of project planning meetings, he is beginning to wonder if his project will ever get off the ground. Tim, a bright young engineer, two years out of graduate school, is excited about his job as a software engineer with a major computer manufacturer. He has worked on several project teams since he joined the firm, and less than three months ago was given his first project to manage. The project, an upgrade of a popular system integration program, was considered important but not overly difficult to manage. Now, reflecting on recent events, Tim is not sure if it is even possible to complete the upgrade.

Problems started almost immediately after Tim was assigned the task of running the project. He set up a series of meetings with senior managers to get their support for the project and commitment of their personnel to staff the team. Quickly it became clear that, while never being overtly hostile, the managers—by and large—viewed his project as intrusive and were reluctant to commit themselves or their resources to his goals.

Tim's frustrations were encapsulated in a recent conversation with a senior manager in the diagnostics department. Diagnostics, charged with debugging all program code, is integral to the success of the program upgrade. Sitting at his desk, reflecting back on his rather one-sided conversation with Ed, the diagnostics manager, Tim felt bewildered and angry by the messages he received.

Tim told Ed, “I have to get a firm commitment from you for two of your people before we can kick off the upgrade project. The preliminary schedule I sent you last week shows they will need to be available on more or less a full-time basis within a month of project start-up.”

“Well, Tim, the problem is that you're doing this at a real busy time in my schedule,” Ed replied. “I'm already running these people at 40-plus hours per week and we're already committed to a full slate of projects into the early part of the fiscal year.”

“Ed, I appreciate your concerns,” Tim said, “but the folks at the top want this project to move fast. You know if we don't meet the September launch window we lose any market advantage the upgrade could give us.”

Ed, clearly becoming irritated, said he knew the schedule, thought it was totally unrealistic and made clear he wouldn't “give up two of his people on a full-time basis when (Tim) whistle(s) for them.”

Trying to control his mounting frustration, Tim replied, “Look, Ed, I know you have your hands full, but if we don't get this project moving, top management is…”

“Is what?,” Ed interrupted. “You keep referring to top management. Who are you talking about? Who's backing this project?”

“Well, you know,” Tim tried to explain, “upper management wants this upgrade on the market as fast as…”

Again interrupting, and now laughing at him, Ed tells Tim, “That's what I thought. Listen, kid, my boss—who is a member of top management—wants me to run this department as efficiently as possible. That means keeping my people at work on their current duties. All I got from you is a memo announcing a new project. Which do you think is more important, a memo from a junior manager or daily calls from the vice president asking me how things are going in the department?”

“So are you saying that you won't cooperate with this project?” asked Tim, now angry and visibly shaken.

“Did I say that?” Ed said innocently. “Of course I'll cooperate with your project, but you'll get your people when I can release them, not when you have ‘got to’ have them.”

After that exchange, Tim had similar conversations with just about every line manager needed to support his project with personnel and resources. Now, sitting at his desk, Tim shakes his head and wonders how his project will get done on time. More importantly, he wonders exactly what he did wrong to bring the project to this state.

Tim's problems are not isolated, nor are they unusual. At some point, almost every project manager has faced the same issues Tim is confronting. Recalcitrant managers, unclear lines of authority, tentative resource commitments, lukewarm upper management support, and hard lessons in negotiation are all characteristics of many project managers’ daily lives. And while the “Eds” of this world typically are somewhat more euphemistic, the message is generally as abundantly clear as the above dialogue. Set in this all-too-familiar framework, it is a wonder that most projects ever get accomplished.

The challenges these project managers face is the byproduct of the power games and political processes that inhabit our organizations. Whether the company is large or small, public or private, direct evidence of constant, frequently stifling political behavior is overwhelming. Indeed, these political activities, not technical problems, are some of the most commonly cited causes for new project failure.

It is ironic that while project management theorists have sought for years to find new and better methods to improve the discipline, power and political behavior—one of the most pervasive and frequently pernicious elements impacting project implementation—has rarely been addressed. Even in the cases where it has been examined, the discussion is often so cursory or theory-driven it offers little in the way of useful advice for practicing project managers. Whatever our current level of understanding of power and politics in organizations, we must realize its presence is ubiquitous, its impact significant, and begin to address it as a necessary part of project management, learning to use it to our advantage increases the likelihood of success.

Before exploring the concepts of organizational power and political behavior, it is important to establish the baseline, or context, of project management in most organizations. In doing so, we will see that the project management function, by definition and constraints, is one of the most natural arenas for political activities within firms.

Introduction to Some Important Terms and Concepts

In an increasingly interwoven and fast-paced corporate environment, projects are the “engines of growth” for most companies. Whether the company regularly employs project teams or creates them as ad hoc “skunkworks” to address immediate crises or market opportunities, the use of projects and cross-functional teams continues to proliferate. At every level of business we find teams of people working on projects, headed by a project manager. Indeed, the use of project management is now a worldwide phenomenon.

The substantial increase in the use of project teams is a mixed blessing for most companies. Research and anecdotal evidence demonstrate tremendous flexibility and improved time to market that project-based work allows modern corporations. However, many companies starting to use project teams for the first time are also discovering the accompanying constraints project-based work offers. Among these are: (1) structural—relating to the way project teams are established and exist vis-à-vis the traditional functional hierarchy; (2) technical—consisting of the determination that the organization possesses the necessary training and technology to efficiently run their projects; and (3) behavioral—suggesting that many project-related problems are the result of human interactions, often due to the newly created cross-functional teams, different operating philosophies and goals held across various departments and levels in companies.

What is a Project?

Although impressive examples of projects abound, actually defining a project is sometimes not easy. The recently opened Eurotunnel (or “Chunnel”), the successful bid for the 1996 Summer Olympic Games by the city of Atlanta, the Great Pyramids of Giza, and the Panama Canal are all famous examples of projects. On a smaller scale, finishing a team project at school, writing a term paper, decorating the house for a Christmas party or a visit from family, or a weekly shopping trip to the grocery store are all projects that we engage in on a daily, almost routine, basis. While vastly different in form, time frame, and objectives to be accomplished, each of the above examples, whether great or modest, share some common properties that define the nature and character of most projects.

In order to be meaningful, we need to consider definitions that are general enough to include a range of organizational activities that comprise “project functions.” At the same time, the definition should be narrow enough so that we are able to focus specifically on those organizational activities that both managers and writers can agree are “project-oriented.” A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, published by the Project Management Institute, offers an excellent definition of projects.

A project is a temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product or service [1].

Using this and other definitions [2], it is possible to isolate some important characteristics underlying projects. Most writers on project management point to four common characteristics:

- They are constrained by a finite budget and time frame; that is, they typically have a specific budget allocated and a defined start and finish date. Further, their budgets often represent a significant portion of the resources of the performing organization.

- They comprise a set of complex and interrelated activities performed by diverse resources or organizational members that require coordination.

- They are directed toward the attainment of a clearly defined objective or set of objectives which, when achieved, mark the end of the project and the dissolution of this project team.

- To some degree, each project is unique.

These features form the core that distinguishes project-based work from other forms of organizational activity. Because they are significant and underscore the inherent challenge in managing projects, it is important to examine each of these characteristics in more detail. In developing a general understanding of projects, the roots of conflict embedded in the characteristics of projects themselves will emerge.

Finite Budget and Schedule Constraints

Unlike ongoing operations that occur within “line,” or functional units of most corporations, projects are set up with two important bounds on their activities: a specified time period for completion and a limited budget. Projects are temporary undertakings, intended to solve a specific problem, not to supplant the regular functional operations of the organization, but rather to operate until the goal is to accomplished. Once these objectives have been achieved, the project ends.

Certainly, we should note that budget and time constraints are estimates, based on the best available—sometimes naively optimistic—information the organization has. As a result, it is not uncommon to build in a margin for error to allow for unforeseen expenses or time slippage.

Given the significant portion of an organization's budget that projects often comprise, it is clear that in making budget and project selection decisions there is a strong propensity for conflict. There are bound to be differences in opinion as to how scarce resources such as money and personnel are used. One obvious reason is that in making such choices we are implicitly, and many times explicitly, making trade-off decisions. It is impossible for the manager to give approval and funding to two competing projects. The decision is made on the basis of a number of criteria that will put the two potential projects, and their prospective project managers, into conflict.

Complex and Interrelated Activities

Projects typically comprise a degree of complexity not found in other functional departments, often due to the cross-functional nature of the activities. For example, in developing a new product, a project team may be staffed by employees from a variety of functional backgrounds: marketing, production, finance, human resources, and others. This cross-disciplinary nature of most project-based work adds another order of magnitude to the usual levels of complexity found within an individual department.

Unfortunately, the complexity and interrelatedness of projects has some unwelcome side effects: power, political processes, and conflict. Political activities and power considerations abound within projects due to the unique properties they possess as well as the multiple goals and attitudes of different members of the project team. Not only are projects forced to compete with functional units for a share of scarce resources but even within the project team the almost ubiquitous nature of conflict is clearly demonstrated. The project team regularly experiences these sources of tension and must seek a balance between dual allegiance to their functional boss and to the project manager.

Another example of the complex and interrelated nature of projects derives from the multiple activities that are carried out, often simultaneously, by different members of the project team. This interrelatedness is typified by the project network diagram used in the Critical Path Method, which demonstrates the sometimes bewildering array of interdependent activities performed by a project team. If tasks are not performed in the correct order and within the time allotted to them, the entire project can be jeopardized. Consequently, the project manager's job here is twofold: first, to establish a coherent working relationship among a number of team members from diverse functional backgrounds; second, to create a planning, scheduling, and control system that permits the greatest level of efficiency of project activities.

Clearly Defined Objectives

Projects are usually created with a specific purpose or a narrowly defined set of purposes in mind. Indeed, the worst sorts of projects are those that are established with vaguely defined or fuzzy mandates that permit a wide range of interpretations among members of the project team and parent organization. Projects of this sort are usually doomed to spin along out of control as objectives are continually interpreted and reassessed while the budget grows and the estimated completion date slips further and further into the future.

An important bit of advice to organizations setting up project teams is to narrow their focus: make the objectives clear and concise. Indeed, it is usually better to create two project teams, each with a smaller set of clearly defined objectives, than to load excessively vague or expansive objectives on a single project. The more well-defined the objectives, the clearer are the indications, both internally and externally, that the project team is succeeding. We often find one of the features of projects that continue to “function” well past the point of serving any reasonable purpose is that either the initial objectives have been altered mid-stream or the objectives were so poorly stated when the project began, they provided no guidance for the team.

Uniqueness

Projects are usually “one shot” propositions; that is, they are nonrecurring and typically established to address a particular problem or market opportunity. Their uniqueness is the characteristic that underscores the challenge of project management—the learning curve from one project to the next is, at best, tenuous. Once a manager becomes part of a functional department involved, for example, with the production of Brand X, that manager will likely continue to face a series of duties and even problems that can be somewhat anticipated due to past experience with similar products manufactured using similar techniques. Past experience—either their own or others—and learning curves will allow that manager to begin to anticipate likely problem areas and points of potential difficulty in the production process. We are able to gain a measure of comfort with the company's manufacturing activities due to our familiarity with how the process has always operated.

The world of project managers is very different. Because we are faced with a unique problem or task, the “rules” for how the project should be run have not been developed. In effect, we have to learn some lessons as we progress. In learning these lessons and exploring virgin territory, project managers encounter the sort of risks and uncertainty that typify project-based work. It is, however, important to note that a project's “uniqueness” may vary considerably from company to company and project to project. A project team for a computer software manufacturer, for example, preparing the fourth upgrade and release of a well-known product will have the experiences of the original development team, plus the three modification teams to draw on in scheduling and coordinating activities. Certainly, recent demands for new features and advancing hardware technology have to be considered and represent a source of uniqueness, but the basic project shares common characteristics that limit the risk inherent in new product development.

What is Project Management?

Given the nature and idiosyncrasies of projects as they have been explicated, how are we to define project management? Simply put, project management is the application of knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques to meet or exceed stakeholder requirements for the project [1]. This definition encompasses a number of distinct and often intimidating challenges. The successful management of projects is simultaneously a human and technical challenge, requiring a farsighted strategic outlook coupled with the flexibility to react to conflicts and trouble areas as they arise. Project managers who are ultimately successful at their profession must learn to deal with and anticipate the constraints on their project team and personal freedom of action while consistently keeping their eyes on the ultimate goal.

But what is the ultimate objective for project managers? What are the determinants of a successful project and how do they differ from projects we consider to be failures. Our initial definition of projects offers some important clues as to how we should evaluate project team performance. Any seasoned project manager will usually tell you that a successful project is one that has come in on time, under budget, and performs as expected (conforms to specifications), commonly referred to as the triple constraint of project management.

In the last few years, we have seen a reassessment of this traditional model for project success. The old triple constraint is rapidly being replaced by a new model, invoking a fourth hurdle for project success: client satisfaction. Client satisfaction is the idea that a project is only as successful as it satisfies the needs of its intended user. As a result, client satisfaction places a new and important constraint on project managers who heretofore have often been evaluated through “internal” measures of success: budget, schedule, and performance. With the inclusion of client satisfaction as a fourth constraint, project managers must now devote additional time and attention to maintaining close ties with and satisfying the demands of external clients. Figure 1.1 illustrates the inclusive nature of project success through adding the fourth success measure.

An implication of this new “quadruple” constraint is its effect on traditional project management roles. Concern for the client, while important, necessitates that project managers adopt an outward focus to their efforts. In effect, they must not only be managers of project activities but now also sales representatives for the company to the client base. The product they have to sell is their project. Therefore, if they are to facilitate acceptance of the project and hence, its success, they have to learn how to engage in these marketing duties effectively.

When project management is viewed as a technique for implementing overall corporate strategy, it is clear that the importance of project management and project managers [3]. Project management becomes a framework for monitoring corporate progress as it further provides a basis on which the skillful manager can control the implementation process. No wonder, then, that there is a growing interest in the project manager's role within the corporation.

The Project Life Cycle

The project life cycle is a common means of helping managers conceptualize the work and budgetary requirements of a project. The concept of life cycles is familiar to most of us; product life cycles—used to explain the sales life and demand for new products, organizational life cycles—used to predict the rise and demise of corporations, and so forth. Likewise, most projects pass through a similar life cycle that project managers find extremely useful for predicting resource needs and budget considerations.

Figure 1.2 is a representation of a project life cycle based on the four-stage model suggested by Adams and Barndt [4] and King and Cleland [5]. In their model, the project life cycle has been divided into four distinct stages or phases:

Conceptualization. This is the initial project stage. During a project's conceptualization, the initial objectives of the project are set as well as possible means to achieve these objectives. Project managers begin to make some personnel selections as they seek to staff their project teams. During the conceptualization phase of the project, actual resource outlay is low, as preliminary assessments are conducted. However, decisions made in this phase often have major impacts on the resources required in later phases and in the operation of the product of the project.

Planning. During the planning stage the project manager is busy conducting preliminary capability studies, assessing the objectives of the project in relation to resource and time constraints. As part of this process, project managers will develop initial schedules, work breakdowns, assign specific tasks to team members. Further, they will make clear to the team how the concurrent and consecutive tasks are structured so team members are able to understand how their individual parts fit into the overall project development picture. Note in Figure 1.2 how the commitment of resources has begun to “ramp up” as increasing levels of money and other resources are committed to the project.

Execution. The third stage involves performing the bulk of the work of the project. Materials, people, and other necessary resources are procured and brought on line as they are needed. The various subroutines and other assigned tasks are being carried out in the proper sequence and performance capabilities of the product of this project are verified. During the execution stage, the project team is operating at maximum strength, with full resources brought into play. It is during this stage that the majority of the budget is spent and the physical product of the project is developed.

Termination. This is the final stage of a project. While the name suggests the project is finished, in reality, it is during a project's termination that a number of important tasks are performed. One of the most significant is the transfer of the project to its ultimate user—the client. Hopefully, as part of the project development process, the project team has kept the client closely informed of the performance characteristics of the product of the project and addressed any of their concerns to facilitate the transfer process. Also during the termination stage, the project manager begins releasing project resources back to the parent organization and reassigns project team personnel to other duties.

How Are Project Teams Structured and Staffed?

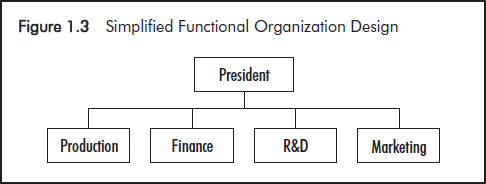

One of the most intriguing and challenging aspects of project management is the relationship of the project team to the rest of the parent organization. With the exception of companies that have matrix or project structures, the majority of organizations using project management techniques employ some form of a standard functional structure. As Figure 1.3 shows, within the classic functional structure, departments are organized in accordance with roles: marketing, finance, R&D, production, and so forth. Most activities and operations occur within these functional groupings. Further, these functional duties are often ongoing and act as necessary parts of the organization's activities. For example, the manager of new business development within the marketing department of a firm doing business with the federal government would be concerned with determining what programs the company will bid, what price it can offer, and the sort of product attributes it can reasonably deliver as part of those bids. In essence, no matter what program the company is bidding on, this activity becomes the manager's full-time job.

When project teams are added to an organization, structural rules change dramatically. Figure 1.4 demonstrates the same simplified functional structure in which project teams have been overlaid. Note the inclusion of the dotted lines from the functional departments of finance, R&D, marketing, and production. The implication of these lines is that when project teams are formed in most organizations that possess functional structures, they are staffed on an ad hoc basis from members of the various departments.

Personnel are assigned to project teams through one of several ways: their services are expressly requested by a project manager who values their competence, they are “exiled” to the project team by a functional boss who is dissatisfied with their work, or they are assigned because they are available. The key, however, is these assignments, like the projects themselves, are temporary. Personnel who staff the vast majority of project teams serve on those teams while maintaining links back to their functional departments. In fact, it is quite common for these individuals to split their time between their project and functional duties. Not surprisingly, this arrangement can lead to a great deal of internal conflict within the project team as each person seeks to create a workable balance between the competing demands of direct supervisors and project team supervisors.

The temporary nature of projects, coupled with the very real limitations on the power and discretion most project managers have, constitutes the core challenge of managing projects effectively. Table 1.1 gives a comparative breakdown of some important distinctions between project-based work and more common department activities.

It is clear the issues that characterize projects as distinct from department work also illustrate the added complexity and difficulties they create for project managers. For example, within a department, it is common to find people with a more homogenous background; that is, the finance department is staffed with finance people, the marketing department is made up of marketers, and so on. On the other hand, most projects are staffed with special, cross-functional teams. These teams are composed of representatives from all the relevant departments and each brings his or her own attitudes, time frames, learning, past experiences, and biases to the team. Creating a cohesive and potent team out of this level of heterogeneity presents a challenge for even the most seasoned and skilled project managers.

Table 1.1Differences Between Department and Project Management

| Department | Project |

| Repeat process or product | New process or product |

| Several objectives | One objective |

| Ongoing | One shot—limited life |

| Homogenous | More heterogenous |

| Well established systems in place to integrate efforts | Systems must be created to integrate efforts |

| Higher certainty of performance, cost, schedule | Higher uncertainty of performance, cost, schedule |

| Part of line organization | Outside of line organization |

| Bastions of established practice | Violates established practice |

| Supports status quo | Upsets status quo |

Source: Graham, R.J. 1989. Project Management as if People Mattered. Bala Cynwyd, PA.: Primavera Systems, Inc.

Likewise, functional activities are intended to reinforce the organizational status quo, the standard operating procedures that are clearly documented in most companies. Project management work is different. As Figure 1.4 shows, project teams operate at the periphery of the organization, pulling human, technical, and monetary resources away from the functional areas for their own needs. Rarely are manuals written on how these project teams are expected to operate. Rather, much of project management involves “violating” such sacred rules as the manner in which members of different functional departments are expected to communicate, the way additional resources are secured, interaction with clients by all members of the project team, and so forth. It is in violating these standard operating procedures that project teams are most effective, operating in a flexible and responsive manner to a variety of internal and external client demands.

As one continues to explore the nature of project management, it becomes increasingly clear that power and politics play a central role in the successful functioning of project managers. The balance of this book will lay out ways to understand and deal with politics, including its use in some of project management's most important activities: conflict resolution and negotiation.