Leading Comprehensive Internationalization on Campus

Introduction

Internationalization efforts on college campuses have been going on for quite a while with various levels of success. In most instances, such efforts have been defined as a way to attract international students to U.S. college campuses and/or study abroad opportunities for American students, as well as occasional area studies programs. However, internationalization is much more than that, and this article attempts to provide a concise roadmap to such efforts, currently defined as Comprehensive Internationalization (CI). The outline provided here aims to aid university management by offering examples of the practice and process of internationalization.

In an effort to broaden internationalization efforts, NAFSA has offered a definition of CI:

Comprehensive internationalization is a commitment, confirmed through action, to infuse international and comparative perspectives throughout the teaching, research, and service missions of higher education. It shapes institutional ethos and values and touches the entire higher education enterprise. It is essential that it be embraced by institutional leadership, governance, faculty, students, and all academic service and support units. It is an institutional imperative, not just a desirable possibility.

Comprehensive internationalization not only impacts all of campus life but the institution’s external frames of reference, partnerships, and relations. The global reconfiguration of economies, systems of trade, research, and communication, and the impact of global forces on local life, dramatically expand the need for comprehensive internationalization and the motivations and purposes driving it (Hudzik, 2011).

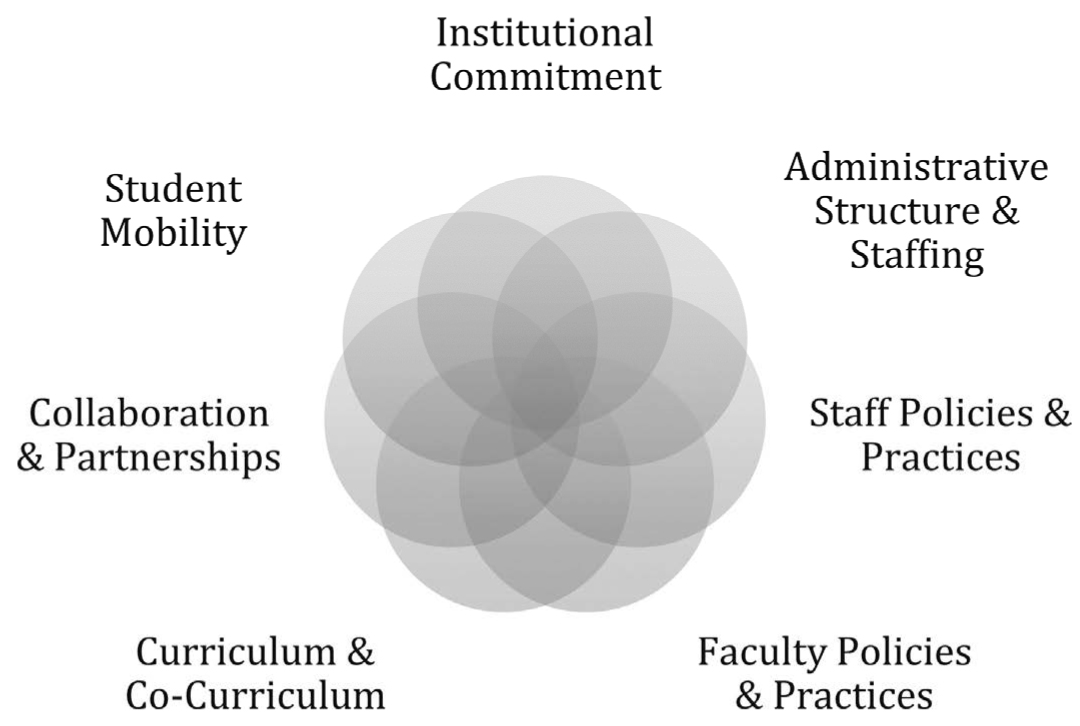

ACE’s (2012) Center for International and Global Engagement (CIGE) has outlined the following elements that make up CI (Figure 7.1):

I. Articulated Institutional Commitment – Mission statements, strategic plans, and formal assessment mechanisms

II. Administrative Structure and Staffing – Reporting structures and staff and office configurations

III. Curriculum and co-curriculum, and learning outcomes – General education and language requirements, co-curricular activities and programs, and specified student learning outcomes

IV. Faculty policies and practices – Hiring guidelines, tenure and promotion policies, and faculty development opportunities

V. Student Mobility – Study abroad programs, and international student recruitment and support

VI. Collaboration and partnerships – Joint degree or dual/double-degree programs, branch campuses, and other offshore programs

An added element of CI should be “Staff Policies and Practices.” Students learn in and out of the classroom, and their lives are affected by both faculty and staff; therefore, staff needs to be part of a comprehensively internationalized institution.

This essay attempts to take the above definition and components of CI and show how to put them into practice by creating a CI plan.

Articulated Institutional Commitment

Any attempt to create a CI program starts with the institutional mission. Increasingly accrediting agencies focus on how institutions meet their stated mission and values, and their adherence to those values. If the mission statement does not formalize a commitment to internationalization and CI is only a “free-standing concept,” it will not happen (Hudzik & McCarthy, 2012). In some cases, even the inclusion of international elements in the mission statement will not mean much unless made explicit in the strategic plan.

Most institutions of higher education today have mission statements that include some type of reference to global or international presence or awareness. Increasingly mission and vision statements sound very similar. However, strategic plans do not necessarily follow up on the mission statements by promoting internationalization.

Even in cases where mission, vision statements and core values, as well as strategic plans include references to global education, relevant assessment mechanisms are missing, as dashboards usually rely on quantitative data such as enrollment, financial condition, and faculty-to-student ratios. Examples of mission statements that embrace internationalization include the following:

• … University provides access to a quality higher education experience that prepares a diverse community of learners to think critically, communicate effectively, demonstrate a global perspective and … (Park University).

• It welcomes and seeks to serve persons of all racial, ethnic, and geographic groups, women and men alike, as it addresses the needs of an increasingly diverse population and a global economy (Texas A& M).

• … also aims, through public service, to enhance the lives and livelihoods of our students, the people of New York, and others around the world (Cornell).

• The university is dedicated to preparing its students for lives of learning and for the challenges educated citizens will encounter in an increasingly complex and diverse global community (University of Kansas).

A number of colleges and universities include some reference to global citizenship or perspective as part of their core values:

• … committed to providing knowledge and skills for life work that will promote the common good of humankind and lead to informed and principled participation in the global marketplace (Bradley University).

• Thinking locally and globally (Union College)

• Effective Global Citizenship (The American College of Greece)

• We challenge our students, faculty, staff and alumni to recognize their responsibility to improve the world around them, starting locally and expanding globally (William Patterson University).

Such mission statements and values have to be reflected in the institutional strategic plan. It is the only way to ensure that the mission and values are carried out, as unlike mission statements, strategic plans are usually assessed.

A CI plan created for Park University was the result of an updated strategic plan, which called for internationalization activities. It started with a goal focused on student success, which included the aim of providing a “globally relevant education.”One objective under that goal was the creation of a Global Institute. To make such goals assessable, the plan called for certain actions to be accomplished by a certain date. An example of a measurable objective was “50% of Park students participate in curricular and/or cocurricular programs and activities offered by, or in collaboration with the Global Institute.”It additionally called for the creation of a CI plan, which would set targets for such things as the percentage of students who pursue Park’s Global Proficiency Certificate.

Under the strategic plan’s priority for “strengthening the brand,” it included an objective that the university would be recognized as providing a “globally relevant education.” A measurable related objective was that there would be a “10% increase annually in the number of students receiving recognition from external entities for activities related to internationalization or multiculturalism.”

However, all strategic plans need to have formal assessment mechanisms, so that they do not remain only on paper. Most institutions use dashboards to present the progress of their strategic plans to their respective boards. However, every unit within that institution should report on an annual basis its progress toward meeting the strategic goals and objectives.

Administrative Structure and Staffing

A commitment to CI must be reflected in the administrative structure and staffing of the institution. At Park University the first step toward CI was the creation of the office of the Vice President of Global and Lifelong Learning, charged with drafting a CI plan and the strategy to internationalize the institution.

Nevertheless, the administration alone cannot take on the task of CI. There must be faculty input and buy-in. For this purpose, a faculty committee on international/multicultural education should exist to provide input, and deal with clearly academic issues related to internationalization, such as the curriculum.

Curriculum and Cocurriculum, and Learning Outcomes

The curriculum is the next important element of a CI plan. Without internationalizing the curriculum, the plan only involves incoming and outgoing students. This is an area that requires bold action.

Curriculum today can be discussed only in the context of competencies and learning outcomes. For example, starting with general education, are there specific global learning outcomes? Some institutions also have institutional learning goals that include international or global competencies.

Park University had established competencies (called “literacies”) long before there was an attempt to internationalize the curriculum. However, the faculty and the deans worked together to add global learning competencies to the already existing ones. Under each of the categories, the faculty added at least one global learning outcome:

Global Learning Literacies

1. Analytical and Critical Thinking

1.5 Synthesize knowledge gathered from different cultures in communication and problem-solving efforts.

2. Community and Civic Responsibility

2.2 Recognize the existence of diverse alternative systems and their necessary global relationships.

2.3 Trace the geographical and historical roots which are shaping these systems.

2.5 Describe the diverse values, beliefs, ideas, and worldviews found globally into personal community and civic activities.

3. Scientific Inquiry

3.6 Demonstrate understanding of the multicultural history and experimental nature of scientific knowledge.

4. Ethics and Values

4.3 Recognize the diversity and similarities in value systems held by different cultures and co-cultures.

5. Literary and Artistic Expression

5.2 Discuss diversities in the visual, verbal, and performing arts and the origins and reconciliation of such diversities.

5.3 Compare and contrast the role of various art forms from a range of societies as both records and shapers of language and cultures.

6. Interdisciplinary and Integrative Thinking

6.2 Synthesize diverse perspectives to achieve an interdisciplinary understanding.

6.3 Discuss the relationships among academic knowledge, professional work, and the responsibilities of local and global citizenship.

These competencies could serve as general education program outcomes, while individual majors could map their own program outcomes to the institutional or general education outcomes. It is imperative that specific measurable objectives and assessment methods are established in order to ensure that such outcomes are met. A few examples from Park University’s CI plan related to program outcomes are listed here:

1. Each academic program has a list of Core Competencies that students should meet before graduating with that specific degree.

a. Ascertain how many of the degree programs, both graduate and undergraduate include at least one Core Competency that is directly tied to any of the Global Learning Literacies.

b. By 2015, 75% of all academic programs will have at least one Core Competency that is directly tied to a Global Learning Literacy.

2. Each course at Park University has a list of approved Core Learning Outcomes (CLO), which are assessed via the Core Assessment.

Goals:

a. Ascertain how many of the Liberal Education (LE) courses include at least one CLO that is tied directly to any of the Global Learning Literacies.

b. Ascertain how many of the courses offered at Park University include at least one CLO that is tied directly to any of the Global Learning Literacies

c. By 2015, 75% of all LE courses will have at least one CLO that is directly tied to a Global Learning Literacy.

d. By 2016, 100% of all LE courses will have at least one CLO that is directly tied to a Global Learning Literacy.

e. By 2015, 50% of all Park courses will have at least one CLO that is directly tied to a Global Learning Literacy.

f. By 2017, 100% of all Park courses will have at least one CLO that is directly tied to a Global Learning Literacy.

Cocurricular Activities

Internationalization can easily be inserted into the cocurricular activities offered to students (see Ward, 2014). These already take place at many institutions and include such things as an international festival, foreign film series, global friendship societies, international buddy system, and many more. Student affairs officers must take the lead in this area and organize activities that not only bring local students in contact with international students but also give all students opportunities to interact with and learn from each other and also interact with the greater community. In Kansas City, one of the city’s largest festivals is the Ethnic Enrichment Festival, which brings over 50 different ethnic groups together to showcase their foods, music, and culture. Freshmen student orientation or some type of student engagement in such activities could easily be accomplished with very little cost.

Since learning takes place through such activities, they should also be assessed. A form of light assessment that some universities offer is an International Certificate for students who engage in international activities. This is similar to a more encompassing approach such as the Cocurricular Transcript that some institutions offer to students, listing their activities during their college years, and thus validating exposure to different ideas and practices, leadership behaviors, and other similar active engagement.

International experiences or global learning should be assessed as part of the normal learning assessment, provided global learning outcomes have been included at the program and/or course level, which many institutions do (Hill & Helms, 2013). Specific assessment tools for study abroad programs also exist, such as the Global Perspective Inventory (GPI), among other tools and rubrics (see Musil, 2006).

Faculty Policies and Practices

Policies and practices related to faculty internationalization efforts include hiring guidelines, tenure and promotion policies, and faculty development. Obviously, this is likely to be a difficult part of the program. However, if internationalization is a priority of the institution, then it must seek to hire faculty that fit this goal. The process can start by simply including the institutional mission statement on any job postings. That would inform prospective employees of the institutional priorities. Other actions in terms of hiring could take the form of noting desired candidate characteristics such as global research initiatives, internationalized courses, and international experiences, so that faculty and staff with such expertise are recruited and hired. During the interview process, some of the questions could be the degree to which a candidate’s courses are internationalized, his or her international research agenda, and other international experiences.

Tenure and promotion criteria could give an extra edge to candidates for tenure and promotion that better fit the institutional mission and core values. At institutions where such criteria area numerical, extra points could be given to these international activities. Faculty development activities could include extra weight to sabbatical applications for work abroad, and of course, adequate funding for legitimate academic travel abroad.

Staff Policies and Practices

Although most documents about internationalization do not include much regarding non-teaching staff, evaluation criteria and especially training and professional development programs for staff should definitively include diversity awareness and training, and even travel abroad opportunities. At one institution, a staff member normally accompanies a faculty member to a service learning spring break program abroad. The only way for staff to handle issues of diversity and international students on campus, and to buy-in to the institutional mission is to get exposure and training. Quite often staff members have longer tenure at institutions than faculty and if they are not part of the program, academic efforts may be throated by complacency and bureaucracy.

Student Mobility

Under most circumstances, institutions usually think of internationalization in terms of receiving international students or sending students abroad. Obviously, in this era of difficult financial constraints, receiving international students has become a priority because of the additional income such students can bring. Besides bringing financial resources to the university, international students can facilitate global learning for local students. Experiences with international students in and out of the classroom help local students learn about differences and similarities with people unlike them. However, careful planning is needed to make sure that a desired balance is achieved not only in terms of the overall percentage of international students but also in terms of students of specific nationalities. Many colleges and universities recruit Chinese students. However, many in China do not look favorably at U.S. institutions that have an extraordinary number of Chinese students, and the more students from one nation the more likely they will interact only with each other; thus, the potential for their easier transition and global learning for local students is lost. Saudi authorities understand this and limit the number of Saudi students not only per U.S. college campus but also per major, and even per U.S. state.

Study abroad experiences for American students have always been a priority for colleges. Such experiences are invaluable and transformative educational tools. Study abroad can take various forms, such as short faculty led programs; college campuses abroad; or individual students going abroad to study. Many study abroad activities increasingly involve third-party providers.

In all cases, it is wise for local officials to visit foreign campuses before sending students there. The American College of Greece, for example, annually invites a handful of study abroad advisers to campus, so they can experience for a few days what their students would experience if they studied abroad there. A good way to facilitate study abroad is through exchange agreements, but this does not work for all institutions and all foreign institutions.

For both international and study abroad students, the most important element is “customer service,” which is often missing. Students need a good orientation, personalized attention, and dedicated services. Students (and their parents) away from home need to feel that they will have all the help they need in a caring environment when away from home.

Collaboration and Partnerships

There is no denying that most interinstitutional Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) stay filed and are never implemented. As such, careful research is needed in deciding the type of agreement to sign and with whom to sign it so that such partnerships are sustainable (Peterson, 2014).

Examples of such collaboration include exchange agreements, joint degree programs, dual-degree programs, branch campuses, and off shore programs (see Helms, 2012). It is beyond the scope of this article to deal with this huge subject. However, for such enterprises, institutions need to consult two sources: their regional accrediting agency for guidelines and their own strategic plans. For example, many potential partners in China would prefer that joint academic programs be done in Mandarin Chinese, which is almost impossible under many accrediting bodies. Very few schools have the ability or desire to create institutional networks such as NYU’s network of campuses around the world. For smaller schools, other more creative ways may be needed. An example is the Global Liberal Arts Alliance (GLAA), a consortium of liberal arts colleges in the Great Lakes region and foreign liberal arts institutions working together to provide various types of experiences for their students.

CI reflects both an attitude and a set of behaviors and practices related to the contemporary needs of university management. It is made up of multiple elements, which are interrelated and whose foundation is an institutional commitment and most desired outcome is student learning.

CI is not just a desire but also a necessity, as quality education today inherently requires global learning. The best way to approach CI is through a commitment and an organized and assessable plan, which has buy-in by various constituencies, it reflects an investment by the institution, and sends a strong message that without global learning students will not be adequately prepared for a globalized environment. University management today cannot afford to ignore the need to internationalize and the best way to tackle this task is through a comprehensive manner.

Figure 7.1 Interrelated elements of comprehensive internationalization.

References

ACE. (2012). Mapping Internationalization on U.S. Campuses: 2012 Edition. Washington, DC: American Council on Education. Retrieved from http://www.acenet.edu/news-room/Pages/2012-Mapping-Inter-nationalization-on-U-S--Campuses.aspx.

Helms, R.M. (2012). Mapping International Joint and Dual Degrees: U.S. Program Profiles and Perspectives. Washington, DC: American Council on Education. Retrieved from http://www.acenet.edu/news-room/Documents/Mapping-International-Joint-and-Dual-Degrees.pdf.

Hill, B.A., & Helms, R.M. (2013). Leading the Globally Engaged Institution: New Directions, Choices, and Dilemmas - A Report from the 2012 Transatlantic Dialogue. Washington, DC: American Council on Education. Retrieved from http://www.acenet.edu/news-room/Documents/CIGE-Insights-2013-Trans-Atlantic-Dialogue.pdf.

Hudzik, J.K. (2011). Comprehensive Internationalization: From Concept to Action: Executive Summary. Washington, DC: NAFSA.

Hudzik, J.K., & McCarthy, J.S. (2012). Leading Comprehensive Internationalization: Strategy and Tactics for Action. Washington, DC: NAFSA. Retrieved from http://www.d.umn.edu/vcaa/intz/-NAFSA_Leading%20Comprehensive%20Internationalization.pdf.

Musil, C.M. (2006). Assessing Global Learning: Marching Good Intentions with Good Practice. Washington, DC: AAC&U. Retrieved from http://archive.aacu.org/SharedFutures/documents/Global_Learning.pdf.

Peterson, P.M., & Helms, R.M. (2014). Challenges and Opportunities for the Global Engagement of Higher Education. Washington, DC: American Council on Education. Retrieved from http://www.acenet.edu/news-room/Documents/CIGE-Insights-2014-Challenges-Opps-Global-Engagement.pdf.

Ward, H.H. (2014). Internationalizing the Co-curriculum: A 3-Part Series. Washington, DC: American Council on Education. Retrieved from http://www.acenet.edu/news-room/Pages/Internationalization-in-Action.aspx.