Global Higher Education: A Perspective from Spain

Introduction

The aim of this article is to present some ideas and data about the role that Spain can play in the global world of higher education, particularly in connection with two continents to which Spain has been historically attached, that is, Europe and Latin America. Spain is now a mid-size country, with a population between 46 and 47 million people. Since 1986 it is part of the European Union and, for historical and cultural reasons, it plays an important role in Europe and prides itself on an impressive artistic and cultural heritage, which dates back to Roman and Medieval times and is particularly rich in the Modern Age. But in addition to this deep European heritage, Spain is also a country with very close relations with Latin America, as large areas of the American territory were conquered and colonized by Spaniards during the 16th and 17th centuries.

Spain’s Academic Reach

As a result of that, some 20 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean speak Spanish and share many cultural traits with Spain. The figures are illustrative: about 430 million people speak Spanish as their mother tongue worldwide, including some 50 million in the United States (usually bilingual speakers of Latin American origin who speak regularly both English and Spanish) (Instituto Cervantes, 2013; Galván, 2014b).

Spanish is thus the mother tongue of more people than those who have English as their native language, although English is of course the international lingua franca, with a total of about 1.5 billion speakers in the world; Spanish is spoken only by a total of about 500 million, counting both native speakers and those who use it as a second or foreign language. That is mainly why the role Spain plays in the world of culture and education is not only restricted to Europe, but it is largely also one that extends to America (particularly Latin America), and is gradually spreading every day to other areas of the world, such as the United States, Asia, and Africa.

The University in Spain has a long history, closely linked to the development of the European university, and some of the current Spanish universities, notably Salamanca, Valladolid, and Alcalá, are among the oldest in Europe. The first Higher Education Institutions (HEIs), then called in Latin Studium Generale (General Study), were established in the late 11th century: Bologna is credited as the oldest one, being created in 1089, soon followed by Oxford around 1096. Others were founded during the 12th century, such as the Studium Generale of Paris in 1150, and still others came later, like Cambridge, whose establishment took place in the 13th century, around 1209. In Spain, the oldest universities that have survived to our days date, like Cambridge, from the 13th century: Salamanca in 1218, Valladolid around 1241, and Alcalá in 1293. All these universities, and others, flourished particularly in the Modern Age, and some of them projected their educational models to America. As is well known, the English and Scottish universities were the models followed in the erection of colleges like those at Harvard (1636), or in what is now Canada, and of course the Universities of Alcalá and Salamanca were taken as models of universities in Latin America, like those founded in the 16th century in Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic), Mexico or Peru, among many others.

The Spanish University system now consists of 82 institutions, 50 of them public and 32 private universities (Conferencia de Rectores de Universidades Españolas, 2013; Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, 2014). Most of the latter have been established in the last 20 years, which means that the public system is predominant in Spain. A public university receives between 60% and 70% of its budget from public funding, either directly or indirectly (through competitive funding for research for instance); the private institutions, however, can only receive public funding under competitive basis for research. The total number of University students is now a little over 1.5 million, 85% of whom pursue their studies at public universities (Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, 2014).

Many of these 82 Spanish universities are also part of the European University Association (EUA), which comprises approximately 850 HEIs from 47 countries, and 17 million students. Because of the existing close links among many universities in Europe, not only through EUA but also by means of other consortiums and common ventures in the EHEA (European Higher Education Area), which includes universities from countries outside the EU, it is no wonder that many European students come to Spanish universities and that many Spaniards pursue their studies at other European HEIs. The best known program for mobility of students and staff in Europe is the Erasmus Program, which has been active since 1987. This program has been very successful so far: during these last 25 years nearly 3 million students have enjoyed academic stays at European universities other than their own for at least one semester, and also more than 300,000 members of faculty and staff have moved to universities in 33 European countries, with public funding from EU and national and regional governments. Within this context, Spanish universities have proved the most active in recent times, to the extent that Spain is now the country with the greatest number of incoming European students (39,300 in the academic year 2012–2013), and outgoing Spanish students to EU universities (39,545 in the same academic year) (Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, 2014).

Internationalization of Spanish Institutions

Most of the European students who come to Spain do so from the largest countries in Europe such as Italy, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Some percentages will help understand what is happening: 35% of Italian students under the Erasmus Program come to Spanish universities; for Britain the percentage is 23%; for France, 22%; and for Germany, 20%. Other smaller countries also send a considerable number of their Erasmus students to Spanish universities: that is the case for Belgium, Cyprus, and Portugal, for instance, with similar percentages to those just mentioned: between 20% and 25%. Ireland, The Netherlands, Poland, and Slovenia send, each of them, nearly 20% of their Erasmus students to Spain. The most popular destinations for Spanish students who go to other European universities are countries such as Italy (22%), France (13%), Germany (11%), and the UK (11%) (European Commission, 2012).

These figures and percentages show the map of relationships and contacts established between Spanish universities and their counterparts in Europe. However, it is important to realize that not only students under the umbrella of the Erasmus Program are concerned, but also faculty and studies. An increasingly cooperative academic and research activity is being developed: joint undergraduate and graduate degrees, collaboration in research projects, joint supervision of doctorates, shared authorship of research papers, etc. The picture provided so far is the one supplied by the most recent figures available (academic year 2012–2013), but the perspective for coming years is certainly more favorable; now the EHEA (also known familiarly as “Bologna agreements”) is fully implemented in almost all European countries. What is to be expected for the future is an increase in this collaborative work between Spanish and other European universities and the development of common degrees and consortiums of HEIs. In this respect, research European programs, such as the new Horizon 2020 (H2020) will naturally boost this at the research level, since the budget for H2020 is nearly €80 billion for the period 2014–2020, addressed mainly to joint proposals (presented by at least three universities from three different countries) to improve scientific excellence, industrial and innovation leadership, and social challenges (Galván, 2014a).

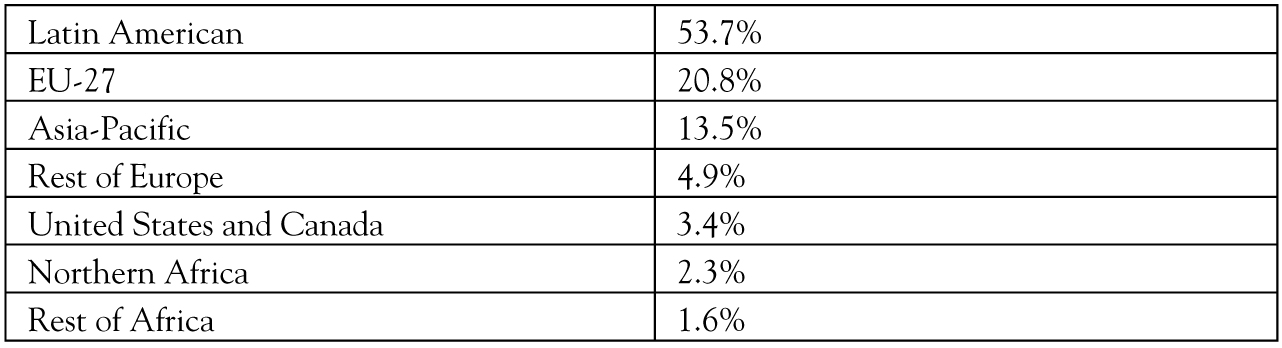

However, as remarked earlier, the academic links for Spanish universities are global. The association with Latin American universities is so strong that many more students come to Spanish universities from Latin America than those who come from other European countries, especially for Graduate Studies, which have a clear influence on research and innovation. Some basic figures follow: although the percentage of foreign students at Spanish universities is still very low (nearly 5% in the last academic year), what is remarkable is that in the case of undergraduates the percentage is extremely low (about 3.7%), whereas for Masters the percentage goes up to 18.4%. Even more remarkable is the origin of those international students. This is shown in Tables 8.1 and 8.2.

Table 8.1 Percentages of International Undergraduate Students in Spain

Table 8.2 Percentages of International Graduate Students (Masters Degrees) in Spain

These figures show very clearly how much the Spanish university system is already contributing to the development of Latin American higher education, particularly in the training of graduate and PhD students, as the lack of faculty with Masters and PhD degrees is perceived by many universities in Latin America as their main current weakness.

Implications of Spain’s Academic Initiatives

The governments of some countries have now established programs with substantial funding in order to alleviate this situation, like Brazil through its “Science without Boundaries” program, or Colombia, Ecuador, and Chile. Other international private organizations, such as Banco Santander through its Universia programs, have launched initiatives to foster mobility for graduate students and internships in industries and in small- and medium-sized companies (Galván, 2014a; Galván, 2014b). It is true that not all actions in these programs are concerned exclusively with Spain, because other countries are also eligible (mainly the United States and other European countries), but the common language and cultural traits between Spain and many of these Latin American countries constitute undoubtedly a powerful pole of attraction toward Spanish universities.

Thus, over the next 20 years, at least Spanish and Latin American universities will face numerous challenges in training, mobility, scientific development, international presence, visibility, and dissemination, which may have a great impact globally. Although it is true that many universities around the world have recently begun to incorporate training their students in English, particularly at the graduate level, this tendency has not yet extended widely through Spain and Latin America. This is probably due to the fact that more than a thousand universities worldwide and large sectors of the world population use Spanish, not English, for everyday communication. It seems self-evident that such an important asset cannot be ignored and that Spanish and Latin American universities are not necessarily to act as if they were Norwegian, Dutch, German, or Polish universities, whose native languages are rarely spoken outside their national frontiers, that is, for universities outside the English-speaking countries, there seems to be little (if any) alternative other than using English if they want to be globally relevant, if they wish to attract international talent and innovation.

However, even if obviously Spanish cannot compete in numbers or international presence with English, for a language spoken by some 500 million people in more than 20 countries the situation looks somewhat different to those other languages spoken by a few million people in limited territories. Let us consider not only that Spanish is a language known and spoken in Spain and Latin America, and in some places in Africa as well, but also that the United States has a population of Hispanic origin, which is now over 50 million people, and which will quite probably (if the statistics are correct) easily reach a hundred million by mid-century. There are in fact hundreds of colleges and universities in the United States where an important number of students and faculty use Spanish on a daily basis. Evidence of this is the influential “Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities” (HACU) (Instituto Cervantes & British Council, 2011).

Concluding Thoughts

The consequences of this situation will probably be, if sufficient funding be allocated by the governments of the countries involved and also by industries and multinational organizations, that more mobility programs will come into effect for both undergraduate and graduate students between Latin American and Spanish universities. This is undoubtedly a major challenge for the social and economic development of many Latin American countries, as they are in urgent need of highly qualified professionals in all the productive sectors and in education. Training these highly qualified professionals in the main Latin American and Spanish Universities is an objective that may be more easily achieved, in a relatively short time, if academic recognition programs are implemented for their undergraduate studies and if mobility is promoted toward the most competitive graduate schools within the Spanish-speaking world. There are universities in Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Spain, and other countries, that, without a shadow of doubt, could make a significant contribution to this mission (Galván, 2014b).

The economic development and spread of many large multinational companies throughout Latin America and Spain provide a rare opportunity for universities, and governments, to reach agreements with these supranational companies and organizations to offer undergraduate and graduate students professional work placements and internships. This would allow students to maximize and complete their university training, while giving also the opportunity to companies and organizations to benefit from highly qualified human assets, students who speak the language of the country and would have no particular difficulties adapting to the culture. Clearly, the advantages are quite evident not only for companies but also for university students, who would acquire professional experience in international centers and organizations, and, of course, for universities, which would extend their educational and intellectual leadership to the productive sector, thereby enriching their graduates’ knowledge and future employability.

Research and innovation, which are mainly developed at the university in most of these countries, would also benefit from these sorts of initiatives. While Latin American and Spanish universities have agreements that allow researchers to cooperate and participate in exchanges, these agreements could surely be extended, if the respective governments so wish, to other public research organizations. This would facilitate the so-called Ibero-American Knowledge Space (“Espacio Iberoamericano del Conocimiento”) by allowing and encouraging the best research groups to cooperate, the coauthoring of scientific works, the publication of scientific periodicals in Spanish, cooperation in business, and technical development. All of the above, evidently, would contribute to the socioeconomic development of these countries and boost greater wealth and prosperity for their citizens (Galván, 2014a).

Spanish-speaking universities, like all those that do not work in English, have an important deficit in indexed journals in Journal Citation Reports (JCR), to the extent that much research that is not published in English does not receive due attention, owing to the low impact of the journals in which it is published. This is immediately apparent if we consult the data: in 2011, 97% of the journals in JCR were published in English, compared with the modest 1.18% in Spanish. It would clearly be unrealistic to think that this data could be changed in the next decades; however, measures might be implemented to improve the situation in specific fields such as the Social Sciences and Humanities journals, where the percentages are slightly higher. A coherent policy, then, to encourage synergies in these areas in the Spanish-speaking context could increase the number of Social Sciences journals, which appear in JCR: 81 journals in 2010 (47 in Spain, 10 in Mexico, 9 in Chile, 6 in Colombia, 4 in Argentina, 3 in Venezuela, and 1 in Brazil and another in the United States), representing 2.97% of the indexed journals in this field (from a total of 2,731 journals, 2,384 were published in English, in other words 87.29%). Spanish is the second language in which most Social Sciences journals appear in JCR, despite the enormous gap compared with English. Boosting studies in this field in Spanish, through university coordination and cooperation, would undoubtedly bolster these publications, thereby contributing to expanding and foregrounding the Ibero-American Knowledge Space globally more effectively (García Delgado, Alonso & Jiménez, 2013; Galván, 2014b).

Hence, if not in other spheres, at least in Humanities and Social Sciences, Spanish-speaking universities do have a role to play on a global scale, and a mission to implement in the coming decades, provided greater cooperation through the measures described above can be achieved. Not only intergovernmental agreements will be necessary, but also bilateral and multilateral cooperation and exchanges between other public and private international organizations, such as, among others, the SEGIB (Secretaría General Iberoamericana), the EU-LAC Foundation, CAF-Development Bank of Latin America, the IAUP (International Association of University Presidents), and the Santander-Universia initiative.

Conferencia de Rectores de Universidades Españolas. (2013). La universidad española en cifras 2012. Madrid: CRUE.

European Commission. (2012). Erasmus –Facts, Figures & Trends. The European Union Support for Student and Staff Exchanges and University Cooperation in 2010-11. Luxemburg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Galván, F. (2014a). Docencia e investigación universitarias en el ámbito iberoamericano. Cuadernos hispanoamericanos, 769–770 (July–August), 39–50.

Galván, F. (2014b). Un espacio de excelencia en español. Nueva Revista de Política, Cultura y Arte, 151, 347–358.

García Delgado, J.L., Alonso, J.A., & Jiménez, J.C. eds. (2013). El español, lengua de comunicación científica. Madrid & Barcelona: Fundación Telefónica & Ariel.

Instituto Cervantes. (2013). El español en el mundo. Anuario del Instituto Cervantes 2013. Madrid: Instituto Cervantes.

Instituto Cervantes & British Council. (2011). Word for Word. The Social, Economic and Political Impact of Spanish and English / Palabra por palabra. El impacto social, económico y político del español y del inglés. Madrid: Instituto Cervantes, British Council & Editorial Santillana.

Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. (2014). Datos y cifras del sistema universitario español. Madrid: Gobierno de España.