Overview—Major Types of Marine Recreation: Climate Change Impacts and Responses

Mark J. Spalding and Luke Elder

Marine Tourism and Climate Change

The marine environment has long been considered one of the most appealing settings for tourism and recreation. Generally, marine tourism includes “those recreational activities that involve travel away from one’s place of residence and which have as their host or focus the marine environment.”1 Marine tourism and recreation include a variety of activities from swimming, scenic boat trips, cruise ships and ferries, sailing, fishing, and wildlife watching, to jet skiing, ocean kayaking, surfing, rowing, and snorkeling. This list is by no means exhaustive, and only catalogues a few examples of the multitude of active and passive marine recreational activities relished by both tourists and coastal residents alike.

Coastal and marine tourism industries depend on agreeable climate and weather, as well as on clean oceans and healthy marine ecosystems. Tourism businesses, along with sectors they support such as agriculture, construction, and artisanal crafts, are affected by tourist demand, which in turn is affected by climate. Weather factors, safety concerns, and recreational opportunities all influence vacation and travel decisions. Extreme weather events, for example, can significantly affect ocean activities and the coastal and island communities to which marine tourists travel. In small island states and developing countries, the changing climate can significantly reduce the number of tourists, impacting one of the main drivers of the economy. Climate change is also driving fundamental changes in the ocean, including sea level rise, storm surges, coastal alteration and erosion, ocean warming, oxygen depletion, and ocean acidification. These conditions are affecting the beaches, coral reefs, fisheries, and other attractions that lure tourists to coastal and marine destinations. At the same time, the tourism industry contributes to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and climate change through the transport of tourists across the world to their favorite coastal and marine habitats, in addition to their consumption patterns upon arrival.

Surfing, sport fishing, diving, and snorkeling (see Image 2.0.1) are all iconic forms of marine recreation that have been affected by climate change, or whose future could be impacted by predicted change. Yet, all have the potential for adaptation to, and even mitigation of, climate change impacts with the proper strategies. In some cases, individuals, businesses, and organizations with interests in these activities have already recognized and are beginning to respond to emerging threats. The following sections describe briefly how these recreational activities are being affected by climate change, and what steps each sector is taking, or could take, to address these impacts. The case studies that follow provide some concrete examples of positive steps already being taken.

Image 2.0.1 Snorkelers swim in a biodiverse coral reef2

Surfing is one of the oldest marine sports, dating back hundreds of years to western Polynesia, where fishermen rode waves back to shore with their daily catch.3 Modern practitioners of this quintessential coastal pastime (see Image 2.0.2) rely on healthy oceans and coasts to give them consistent and predictable waves. However, most surfers today agree that climate change has already started to alter their favorite sport in a variety of ways. Chad Nelsen, CEO of the Surfrider Foundation, sums up the issue this way: “The impacts associated with climate change are the biggest issues [facing surfers]. . . [W]arming oceans, sea level rise and ocean acidification are threats. . .that are going to affect all of us at the local level and at our favorite surf spots around the globe. We not only need to start reducing emissions, but also plan to adapt to the changes that are already underway.”4

Image 2.0.2 A surfer enjoys a day in the water9

Melting glaciers and ice sheets, along with thermal expansion of the ocean, are causing sea level rise, which changes where and how waves break on reefs and shorelines. Extreme beach erosion, coastal alteration, rising high tides, coral reef decline, and permanent high tides are all causing wave patterns to shift.5 Increased nuisance flooding, as well as shrinking beaches and higher tides, may reduce beach access, temporarily or permanently.6 The sizes and styles of waves are changing, with some shrinking and others growing.7 In short, climate change threatens many aspects of surfing, from where and when it can take place to the tourism industry that it supports.8

Specific Threats from Climate Change

All major surf swells in the world, including those in Hawaii, Fiji, Tahiti, and numerous other places, are located over shallow coral reefs. These create reef breaks, fast and hollow swells that surfers tout as the most consistently flawless waves. Big wave breaks rely on healthy and functioning coral, and more generally, on a healthy and functioning ocean.

A major driver of change to surfing is ocean acidification, caused by the ocean’s uptake of excess carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere. Acidification is fundamentally changing the chemistry of the ocean.10 Seawater has become 30 percent more acidic on average, forcing many calcareous (calcium carbonate) marine organisms, including corals, to struggle to maintain their normal physiology.11 As the formation of new coral declines, the impacts of storms and other events that erode and damage reefs will be more pronounced. While the devastating impacts of coral reef decline on global fisheries and biodiversity have been discussed in Volume I, from a recreational perspective, the decline of reefs could have major impacts on surfing, as many important reef breaks, such as Hawaii’s Pipeline, become a thing of the past.

A second major threat is the increased frequency and intensity of coastal storms, especially when combined with rising sea levels. Storm surges, flooding, and erosion can permanently alter the coastlines and communities on which surfers depend. Storms cause sand displacement and shift wave patterns, making them less predictable. An extreme storm event can result in permanent change to an iconic surf spot, causing losses to the surf community, the local residents who rely on the surfing industry, and the marine habitat. And while larger ocean storms can mean “epic swells” for surfers, they can also change beaches and wave patterns to the extent that classic surf spots are no longer usable, or become too dangerous for recreational surfing. At the other end of the spectrum, some parts of the planet might actually see fewer storms and big wave events.12 Meanwhile, sea level rise could make certain beaches, including famous low tide surfing areas such as California’s Rincon and Pleasure Point, essentially useless for surfing.13

Mitigation and Adaptation

Most traditional responses to the effects of climate change on the ocean do not help surfers, and in fact, can diminish beaches and coastlines. Beach filling, storm walls, and beach armoring often destroy beach function, and do not always increase long-term coastal resilience. There are some successful mitigation and adaptation solutions, however, to problems affecting the surfing community. Seagrass and mangrove protection and restoration can mitigate the impacts of storm surges and help naturally increase coastal resilience while not harming surfing conditions. “Low impact” surf contests and camps are designed to minimize environmental impacts, including climate change, through carbon offsets and other tools.14 Even biodegradable “green” surfboards help by lessening the impact of surfing on the climate in general.15

Multiple NGOs and the surfing community are taking action to tackle these issues. The Surfrider Foundation, an international network of surfer activists, works diligently on these problems; currently, there are over 100 outreach and advocacy campaigns, including over 30 on coastal and ocean protection.16 Sustainable Surf, a nonprofit founded by social entrepreneurs, uses surfing as an on-ramp to discussing these complex, and politically charged, issues. Their Deep Blue Surfing Events help “reduce direct threats to the sport of surfing from global climate change (such as sea level rise, ocean acidification, and loss of coral reefs).”17 Save the Waves is a nonprofit dedicated to protecting coastal ecosystems through innovative strategies, often in partnership with local communities, for the benefit of surfers as well as all coastal recreational tourists.18 In addition to grassroots surf organizations such as these, professional surfing athletes can, and do, serve as spokespeople for action on climate change and ocean acidification.

Diving and Snorkeling

Diving and snorkeling represent major tourist activities in the Caribbean and other coastal and island locations around the world. An important ingredient is coral reefs, with their colorful assemblages of corals, sponges, anemones, fish, and other marine life (see Image 2.0.3). In a recent story on the Frommer’s travel website touting the Caribbean’s ten best snorkeling sites, for example, nine of those sites were noted for their reef habitats.19 Coral reefs contribute directly to the roughly US$2.1 billion per year that the dive industry contributes to the Caribbean economy.20 In fact, this industry, and the jobs created, would be virtually nonexistent without reefs to attract divers and snorkelers.

Image 2.0.3 A SCUBA diver explores a colorful coral reef21

Healthy coral reefs draw divers, snorkelers, and other tourists from all over the world. But decreased reef diversity due to overfishing, ocean warming, and decalcification threatens this type of tourism. Ironically, as tourists travel across the world via car, plane, and boat to visit famous coral reef dive sites, they contribute to climate change and add to the impacts that are destroying these spectacular habitats. As no one wants to see a dying or dead reef devoid of fish, tourism rates in many coastal communities could decline along with local reefs, and livelihoods dependent on dive tourism will be affected.

Specific Threats from Climate Change

Rising sea levels, increasing water temperatures, and ocean acidification all threaten the future of coral reefs. As with seagrass habitats, some reefs will become too deep to receive sufficient sunlight to survive and thrive. Increased sea surface temperatures contribute to coral bleaching, a stress response that prompts corals to expel their essential symbiotic algae. This causes corals to turn white, lose their major food source, and become more susceptible to diseases (see Case Study 2.1 in Volume I). Ocean acidification, meanwhile, prevents corals from forming strong skeletons due to a decrease in available calcium carbonate. One study estimates that reef-building corals will calcify up to 50 percent less, relative to pre-industrial rates, by the middle of this century.22

Ocean acidification also affects the sea life around coral reefs. In a study off Papua New Guinea, scientists found that when pH dropped to 7.8, coral reef diversity declined by as much as 40 percent.23 A loss of reef-building organisms not only threatens both the geological and biological identities of coral reef ecosystems, but also their attraction as popular tourist destinations. Unhealthy reefs are less productive, have fewer fish, and are less biodiverse, all of which discourage tourists to dive, snorkel, and recreate in them.

Mitigation and Adaptation

General strategies such as continuing research, reducing water pollution, and monitoring coral reef health could help safeguard healthy and vibrant dive sites for the next generation. Sustainable Travel International (STI) has launched a climate-friendly scuba dive program, including the world’s first custom carbon dive calculator, to address dive industry impacts on climate change.24 The calculator determines the carbon footprint from a dive trip, including air travel and diving activities, and compensates for these emissions by funding carbon offset programs.25

The Ocean Foundation has developed an innovative carbon offset program, SeaGrass Grow, which employs the first-ever verified seagrass offset methodology.26 SeaGrass Grow is designed to restore seagrass meadows along our coastlines. Its main objectives are to restore habitat, educate the public, support coastal community resilience and economic stability, and offset carbon emissions. SeaGrass Grow launched its voluntary offset Blue Carbon Calculator in 2008, and since then, has offset emissions for corporations, nonprofits, restaurants, and event coordinators. These efforts acknowledge that everyone, including tourists, is responsible for climate change and can be part of the solution.

Recreational Fishing

Drive down any coastline and you are likely to see local residents or tourists with fishing rods in their hands and lines in the water. Recreational fishing supports more than 828,000 jobs in the United States, with an estimated 33 million people spending US$48 billion annually on the sport.27 In the Caribbean, recreational saltwater fishing is a major part of the economy for many islands and communities, as well as an important component of the tourism industry. While no regional figures are readily available, a study of Costa Rica estimated that the direct and indirect economic impacts of American and Canadian sport fishers is over US$1 billion each year.28 This suggests that the annual contribution of this sector to the Caribbean economy is in the tens of billions of dollars.

Specific Threats from Climate Change

The greatest single threat to saltwater sport fishing might be the impacts of climate change on fish populations. Rising sea levels contribute to the loss of valuable habitats that provide protection and food resources for juvenile fish. For mangroves, a critical coastal habitat for fish and other marine life, sea level rise causes sediment erosion, inundation stress, and increased salinity, all of which pose problems. For seagrass meadows, another important ecosystem, increased water depth restricts the amount of light reaching grasses, reducing their photosynthesis, productivity, and geographic range. Changes in tides, water currents, and turbidity can impact the growth, reproduction, and propagation of seagrass. Loss of this essential habitat for juvenile fish will undoubtedly impact recreational fishing for the worse. Warmer waters can also damage coral reefs, yet another critical habitat for fish.

Changes in ocean temperatures can also affect fish health, reproduction, and survival. In the past century, sea surface temperatures rose at an average rate of 0.13°F per decade.29 Along with other changes, this warming significantly influences fish metabolism, growth rate, productivity, seasonal reproduction, and susceptibility to diseases and toxins. In addition, changes in ocean temperatures can force species to change locations, or open new areas to predators including invasive species, disrupting food chains and ecosystems. Fish stocks already in decline due to overfishing and habitat destruction must also face the threat of ocean acidification. Pteropods, the base of the food chain on which bigger fish feed, are having difficulty forming calcium carbonate shells due to more acidic waters.30 Ocean acidification has also reduced the ability of fish larvae to find suitable habitat, orient themselves, and find their way home.31 Fish eggs are much more sensitive to acidity changes than adult fish and may dwindle with decreasing pH.32 All of these changes make it harder for fish to survive and grow big enough, or in large enough numbers, to be useful for recreational angling.

Mitigation and Adaption

Various mitigation strategies can help to protect the recreational fishing industry and the fish populations on which the industry relies. Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) can protect fisheries and ecosystems while also promoting tourism as part of their management planning (see Volume I, Essay 4.1). In well-managed MPAs, tourists can see endangered species, coral reefs, and beautiful beaches, all of which broaden coastal communities’ economic options and revenue streams. Tourists can pay fees to support conservation and the livelihoods of local residents, and in turn, are able to fish in pristine and protected marine environments. MPAs can help to ensure sustainable fisheries by protecting certain types of fish, allowing them to grow to a large size and reproduce before being caught, thereby increasing the value of the reserve and of fishing and tourism in the waters around it. Protected areas can also improve the ability of local communities to obtain fish for food, especially if wild populations are supplemented with sustainable aquaculture.

Another strategy is to create programs that help diversify livelihoods, including investing in marine tourism and aquaculture. Programs can improve communication, collaboration, and information sharing on climate change and fisheries adaptation. The ecosystem approach to fisheries (EAF) management, which encompasses the marine environment and targets commercial fish stocks through adaptive management, is an example of this strategy. Access to larger, more sophisticated vessels with multi-fisheries capabilities allows recreational fishermen to travel farther and move to different locations that offer better fishing opportunities, diversified fishing activities, and a wider range of species and stocks to fish.

Conclusion

Surfers, sailors, divers, ecotourism companies, eco-resorts, and all those who enjoy the ocean have the responsibility and power to bring this issue to the forefront and demand action so we can go on enjoying our ocean. We need to improve climate research, monitoring, and forecasting, and to support sustainable tourism, fishing, and development. These actions, combined with stewardship of our invaluable coastal and marine natural resources, can help ensure that people will continue to be awed and entertained by a day at the beach or on the water.33

Notes

1. Mark Orams. (1999). Marine Tourism Development, Impacts and Management. London: Routledge.

2. Image Source: Chris Guinness. Used with permission from The Ocean Foundation.

3. Matt Warshaw. (2010). The History of Surfing. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. (It should be noted that the first wave-riders remains a contested title, with claims from ancient Peru, Hawaii, and Polynesia, among others.)

4. Pat Fallon (Interviewer) and Chad Nelsen. (Interviewee). (2015). “Surfonomics with Surfrider CEO Chad Nelsen” [Interview transcript]. Whalebone Magazine. http://whalebonemag.com/two-coasts-one-ocean-surfonomics-with-surfrider-ceo-chad-nelsen/

5. MoStoke.com. (2017). “How Will Rising Sea Levels Change our Breaks?” http://homesolarus.com/gridfreedom/read/tag/permanent-high-tide/

6. Holly Bamford. (2015.) “Nuisance Flooding: Communities Working to Overcome this Worsening Symptom of Sea Level Rise.” Medium. https://medium.com/@NOAA/nuisance-flooding-7cea715ab8f6

7. James Urton. (2015). “Climate Change May Flatten Famed Surfing Waves.” San Jose Mercury News. http://phys.org/news/2015-02-climate-flatten-famed-surfing.html

8. Brian Merchant. (2013). “Global Warming is Going to Ruin Surfing for 25% of the Planet.” Motherboard. http://motherboard.vice.com/blog/global-warming-is-going-to-ruin-surfing

9. Image Source: Martin Garrido. Used with permission from The Ocean Foundation.

10. Jeremy T. Mathis, Jessica N. Cross, Wiley Evans, and Scott C. Doney. (2015). “Ocean Acidification in the Surface Waters of the Pacific-Arctic Boundary Regions.” Oceanography 28(2), 122–135. http://dx.doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2015.36

11. Jeremy T. Mathis, Jessica N. Cross, Wiley Evans, and Scott C. Doney. (2015).Op cit.

12. Andrew J. Dowdy, Graham A. Mills, Bertrand Timbal, and Yang Wang. (2014). “Fewer Large Waves Projected for Eastern Australia Due to Decreasing Storminess.” Nature Climate Change 4, 283–286. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2142.

13. Sam Kornell. (2012). “Will Climate Change Wipe Out Surfing?” Pacific Standard. http://www.psmag.com/books-and-culture/will-climate-change-wipe-out-surfing-44209

14. Beachapedia. “Low Impact Surf Contests.” http://www.beachapedia.org/Low_Impact_Surf_Contests

15. Pat Fallon. Surfonomics with Surfrider CEO Chad Nelsen [Interview, 2015]. Whalebone. http://whalebonemag.com/two-coasts-one-ocean-surfonomics-with-surfrider-ceo-chad-nelsen/

16. Surfrider Foundation. “Campaigns.” http://www.surfrider.org/campaigns

17. Sustainable Surf. “Current Projects.” http://sustainablesurf.org/projects/

18. Save the Waves Coalition. “Programs.” http://www.savethewaves.org/programs/

19. Frommers. “The 10 Best Caribbean Snorkeling Spots.” http://www.frommers.com/slideshows/847912-the-10-best-caribbean-snorkeling-spots#slide848061

20. Lauretta Burke and Jon Maidens. (2004). Reefs at Risk in the Caribbean. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute (WRI). http://www.wri.org/publication/reefs-risk-caribbean

21. Image Source: NOAA. Used with permission from The Ocean Foundation.

22. Joan A. Kleypas and Chris Langdon. (2006). “Coral Reefs and Changing Seawater Chemistry.” In Coral Reefs and Climate Change: Science and Management, eds. Jonathan T. Phinney, William Skirving, Joanie Kleypas, and Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, 73–110. Washington, DC: American Geophysical Union.

23. Katharina E. Fabricius, Chris Langdon, Sven Uthicke, Craig Humphrey, Sam Noonan, Glenn De’ath, Remy Okazaki, Nancy Muehllehner, Martin S. Glas, and Janice M. Lough. (2011). “Losers and Winners in Coral Reefs Acclimatized to Elevated Carbon Dioxide Concentrations.” Nature Climate Change, 1, 165–69. doi:10.1038/nclimate1122.

24. Sustainable Travel International. (April 2007). “Scuba Dive Industry Addresses Global Warming and Climate Friendly Diving.” Responsible Travel Report. http://www.responsibletravelreport.com/sti-news/news/2241-scuba-dive-industry-addresses-global-warming-and-climate-friendly-diving

25. Carbon offsets pay for reforestation programs and other methods that help “offset” the CO2 emissions of travel and other human activities, thereby reducing global carbon levels.

26. The Ocean Foundation. “SeaGrass Grow.” http://www.seagrassgrow.org/index.php?ht=a/GetDocumentAction/i/3571

27. American Sportfishing Association. (January 2013). Sportfishing in America: An Economic Force for Conservation, 2. http://asafishing.org/uploads/2011_ASASportfishing_in_America_Report_January_2013.pdf

28. Max Alberto Soto Jimenez, Marlon Yong Chacon, Alejandro Gutierrez Li, Carolina Fernandez Garcia, Rudolf Lucke Bolanos, Freddy Rojas, and Gabriela Gonzalez. (May 30, 2010). Analysis of the Economic Contribution of Recreational and Commercial Fisheries to the Costa Rican Economy. San Jose: Instituto de Investigaciones en Ciencias Economicas of Universidad de Costa Rica, Sponsored by The Billfish Foundation. https://www.igfa.org/images/uploads/files/costaricamarinefisherieseconomics5-30-10.pdf

29. NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). 2015 update to data originally published in: NOAA. (2009). Sea Level Variations of the United States 1854–2006. NOAA Technical Report NOS CO-OPS 053. www.tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov/publications/Tech_rpt_53.pdf

30. James C. Orr and Victoria J. Fabry, et al. (2005). “Anthropogenic Ocean Acidification Over the Twenty-First Century and Its Impact on Calcifying Organisms.” Nature, 437, 681–86.

31. Philip L. Munday, Danielle L. Dixson, Jennifer M. Donelson, Geoffrey P. Jones, Morgan S. Pratchett, Galina V. Devitsina, and Kjell B. Doving. (2009). “Ocean Acidification Impairs Olfactory Discrimination and Homing Ability of a Marine Fish.” Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences, 106(6), 1848–52. doi:10.1072/pnas.0809996106.

32. Andrea Y. Frommel, Rommel Maneja, David Lowe, Arne M. Malzahn, Audrey J. Geffen, Arild Folkvord, Uwe Piatkowski, Thorsten B. H. Reusch, and Catriona Clemmesen. (2011). “Severe Tissue Damage in Atlantic Cod Larvae Under Increasing Ocean Acidification.” Nature Climate Change. 2, 42–46. doi:10.1038/nclimate1324

by Travis Bays and Shengxiao Yu

Located on the Southern Pacific coast of Costa Rica, Bodhi Surf + Yoga is a tourism business that is purpose-driven at its core. Bodhi (which means “awareness” in Sanskrit) shies away from providing an all-inclusive experience to its guests. Bodhi staff see fostering a relationship between guests and locals as integral to the mission and want guests to explore the community on their own.1

Bodhi Surf + Yoga is run by two couples and longtime friends who are committed to providing personalized and intimate experiences for guests. As coastal business owners and surfers, Bodhi staff spend a lot of time in the ocean and see it as their second home. They also see firsthand the impact of human activities on the ocean ecosystem. Bodhi staff share this love of and commitment to the ocean with guests by giving them an up-close experience with the ocean, and then, encouraging them to become committed to its protection. Staff members are involved in every part of the guest experience, including trip planning, in-country support, community engagement, hosting the guests at the Bodhi Lodge, and providing surf and yoga instruction.

Addressing Climate Change Through Partnerships

Corporate social responsibility has become the bandwagon of the day, with many businesses looking at impact investment and the triple bottom line (people, planet, profit). While some of these efforts have made changes in communities, they are largely based on what corporate social responsibility teams design for communities, sometimes in isolation from communities. In contrast, Bodhi Surf is a small business with staff who are residents of and immersed in the community, and who work in partnership with local NGOs. They listen to the voices of other residents and address the effects of climate change in context.

Partnerships grounded in the local community

Bodhi Surf + Yoga is located between the villages of Uvita and Bahia Ballena, often referred to together as Bahia-Uvita (see Image 2.1.1). Similar to coastal communities around the world, Bahia-Uvita is experiencing the distressing effects of climate change. Nearby reefs have a high sensitivity and low adaptability to increased temperatures and decreased precipitation, and declining reef health has negatively impacted coastal communities. Bahia Ballena is also vulnerable to coastal erosion, coral bleaching, increased storms, and other impacts of climate change. Bodhi Surf + Yoga participated in a recent climate change diagnostic and uses the recommendations to focus its work on climate change, which include promoting biodiversity, maintaining and restoring vegetation around beaches, ensuring proper wastewater management, implementing community education programs, and analyzing visitors’ impacts on the community.

Image 2.1.1 The symbolic Whale Tail of the Marino Ballena National Park, Bahia Ballena-Uvita, Osa2

Due to Bodhi Surf + Yoga’s deep connection to Bahia Ballena-Uvita, it has always made investing in the community the core of its mission. Since its inception, Bodhi has donated time, energy, and resources, both human and financial, to the community. Bodhi works principally with two local NGOs, Geoporter and Forjando Alas. Geoporter provides geospatial technology education to improve the community’s understanding of its environment,3 while Forjando Alas is an after-school program aimed at creating a safe space for kids to learn life skills (see Image 2.1.2).4 Geoporter has conducted several GPS data collection activities to map the locations of trash in the streets of Uvita. These activities were carried out by Forjando Alas students, who learn about geospatial technology by applying it to their own community. The students have analyzed the data to map the greatest concentrations of trash in order to engage in targeted public awareness campaigns. Geoporter also conducts other sessions where students explore different physical landforms around the world and study conservation efforts to protect various animal species.

Image 2.1.2 Students in the Forjando Alas after-school program learn how their actions can affect the world5

Every month, Bodhi Surf + Yoga also hosts Surf and Service Saturdays to give free surf instruction to local youth in the Forjando Alas program, in exchange for community service hours to address a climate-related issue (see Image 2.1.3). By donating a few staff hours to more than ten kids each week, Bodhi amplifies its impact by addressing urgent environmental needs and raising environmental consciousness among the youth. Geoporter and Forjando Alas staff have also participated in the Surf and Service Saturdays program.

Image 2.1.3 Local youth in Bahia Ballena-Uvita, Osa, take part in a neighborhood cleanup program as part of “Surf and Service Saturdays”6

Partnerships with Global Impacts

Beyond local partnerships, Bodhi uses its position as a tourism company to extend its impact to the global level. It does this in two main ways: through a travelers’ philanthropy program that seeks to change tourists’ behavior over the long term, and through partnerships with educational institutions and international NGOs.

Travelers’ philanthropy program

In July 2014, Bodhi Surf + Yoga launched its travelers’ philanthropy program,7 in collaboration with the Costa Rica-USA Foundation for Cooperation and its affiliate, Amigos of Costa Rica.8 Bodhi broke away from the traditional model of soliciting funds from guests, and instead, decided to donate 2 percent of its profits from vacation packages to its local NGO partners, Geoporter and Forjando Alas. Guests are informed of this gift in their thank-you email. They are also invited to match or give more than the gift card amount, and to share the story of Bodhi and its local NGO partners with their families and friends. This model allows for a deeper (and longer-lasting) engagement with travelers. It says thank you for investing in the community by choosing Bodhi Surf + Yoga; it fosters reflection from the travelers once they leave Bahia Ballena-Uvita; and it amplifies Bodhi’s community impact to a global audience.

Ocean Guardian pledge

Tourists often experience transformative thoughts while traveling, especially when they intimately experience the environment. Many people, however, let that transformation fade once they arrive back at their normal life. Bodhi Surf + Yoga attempts to capture that transformation to foster “ocean guardians” who will translate mental realizations into actions that are woven into the travelers’ normal lives to make sustained impact. Through its Ocean Guardian Journey program, Bodhi uses its personal relationships with guests to create sustained behavioral changes that protect the ocean.

Before guests leave Bodhi, they are encouraged to sign the Ocean Guardian Pledge9 to commit to actions that protect the ocean in their daily lives. Travelers who sign the pledge receive monthly e-mails with concrete actions to reduce their environmental impacts, such as using reusable shopping bags, learning about responsible travel, organizing a carpool, and performing a home energy audit. By making such simple changes, people can make their lives more sustainable. Former guests also receive gift cards that they can redeem at Amigos of Costa Rica, an NGO that raises funds to support sustainable change in Costa Rica through education, capacity building, conservation, and science and technology (see Image 2.1.4).10

Image 2.1.4 The Ocean Guardian Travelers’ Philanthropy Gift Card reminds visitors of their pledge to help protect the world’s oceans11

By experiencing the ocean through Bodhi Surf + Yoga, travelers are inspired through the Ocean Guardian Journey program to remember their connection to the ocean and implement changes in their daily lives. One former guest of Bodhi, Lisa Burton, wrote on TripAdvisor that “despite coming from the landlocked state of Minnesota, our 10,000 lakes allow us to take this pledge and take responsibility for our local waterways as well as the oceans to our east and west. Upon our departure, the Bodhi owners gave us a blue marble to signify the ocean and serve as a reminder of our greater responsibility to the environment (see Image 2.1.5).”12

Image 2.1.5 Spreading the Blue Gratitude one marble at a time13

Educational partnerships

Bodhi Surf + Yoga partners with various educational organizations, including universities and colleges, as well as NGOs, to spread its message and inspire action among students and youth. Bodhi often hosts students from Global Leadership Adventures (GLA), a service learning organization that provides opportunities to high school students to work with community-based businesses and organizations.14 Every year, Bodhi hosts five groups of approximately 20 students each for GLA’s Costa Rica: Protecting the Pacific program, with each group working with a local NGO partner.15 Members of the Bahia Ballena-Uvita community appreciate the opportunity to engage with GLA students, as it deepens their exposure to people from other places. The personal relationships fostered are paramount to doing effective work grounded in the local community and amplified to the global stage.

Recently, researchers from Skidmore College in New York State (USA) conducted a study to understand how participation in the GLA program at Bodhi affected students’ commitment to volunteerism, environmental attitudes and behaviors, and involvement in environmental issues. Preliminary results from this study showed significant increases in environmental knowledge and positive changes in attitudes among the GLA participants with Bodhi Surf + Yoga. Prior to their GLA trip, 65 percent of students could not describe environmental issues facing Costa Rica. After the trip, the majority of students showed a deeper understanding of the impacts of hotel and resort development, consumer habits, and plastic usage on the coastal environment.

Using Bodhi Surf + Yoga as a case study, researchers from The Pennsylvania State University in the United States are conducting a long-term study to see how a nature-based tourism experience can impact a traveler’s pro-environment behavior.16 The study will assess how behavioral changes, advocacy, and activism in favor of environmental conservation can be inspired by a travel experience. The study examines the influences of both the onsite experience at Bodhi and the Ocean Guardian Journey campaign.17 This research will provide concrete data on Bodhi’s impact on visitors, as well as a deeper understanding of its role in confronting climate change and promoting a more sustainable environment.

Conclusions

At Bodhi Surf + Yoga, surfing and yoga are not just physical activities, but lifestyles that are aligned with conservation and environmentalism (see Image 2.1.6). Surfers spend more time in the ocean than most people and are very aware of the state of their favorite surf spots and the ocean in general. Learning to surf at Bodhi means learning pro-environmental behaviors, which are at least as important as standing up on a surfboard. Yoga, which helps provide physical and spiritual awareness, allows prana—the vital life force of all living things—to enter the yoga practitioner. This allows for the development of consciousness and respect for all living things, also known as awakening.

Image 2.1.6 A fundamental assumption of Bodhi Surf + Yoga, and other tourism experiences grounded in natural and human connections, is that you will protect what you love18

Bodhi Surf + Yoga is directly dependent on the well-being of the surrounding community as well as on local terrestrial and marine ecosystems. After all, the beauty of the local environment and the cultural richness of the community are what attract visitors in the first place! For that reason, Bodhi has a vested interest in ensuring the health and well-being of these entities and encouraging others to do the same. Through these efforts, and those of the community and global partners, Bodhi not only provides a world-class nature tourism experience, but educates patrons about climate change and other environmental issues, and inspires them to take more responsible actions at home.

Notes

1. Bodhi Surf School. “Why Choose Bodhi Surf School.” http://www.bodhisurfschool.com/why-bodhi-surf

2. Image Source: Andres Madrigal.

3. Geoporter. “Welcome to Geoporter.” http://geoporter.net/

4. Forjando Alas. http://forjandoalas.org/

5. Image Source: Shengxiao Yu.

6. Image Source: Melissa Rejeb.

7. For more on Travelers’ Philanthropy, see www.responsibletravel.org

8. Amigos of Costa Rica. (2017). “Ocean Guardian Journey: A Travelers’ Philanthropy Program.” https://www.amigosofcostarica.org/projects/ocean-guardian-journey

9. Bodhi Surf School. “Ocean Guardian Pledge.” http://www.bodhisurfschool.com/ocean-guardians/pledge

10. https://amigosofcostarica.org/

11. Image Source: Amigos of Costa Rica.

12. TripAdvisor. “Bodhi Surf School (Uvita, Costa Rica) - Reviews.” http://www.tripadvisor.com/Attraction_Review-g635755-d1918722-Reviews-or20-Bodhi_Surf_School-Uvita_Province_of_Puntarenas.html#REVIEWS

13. Image Source: Melissa Rejeb.

14. Global Leadership Adventures. (2016). “Costa Rica - Protecting the Pacific.” https://www.experiencegla.com/destinations/teen-programs-latin-america/costa-rica/costa-rica-protecting-pacific/

15. Global Leadership Adventures. (2016).

16. Carter Hunt, William Durham, Laura Driscoll, and Martha Honey. (2015). “Can Ecotourism Deliver Real Economic, Social and Environmental Benefits? A Study of the Osa Peninsula, Costa Rica.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(3), 339–357.

17. Mele Wheaton, Nicole Ardoin, Carter Hunt, Janel Schuh, Matthew Kresse, Claire Menke, and William Durham. (2016). “Using Web and Mobile Technology to Motivate Pro-Environmental Action After a Nature-Based Tour.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(4), 594–615.

18. Image Source: Melissa Rejeb.

Linking Marine Recreation and Marine Protected Areas: A Marine Scientist and Lifelong Diver’s Point of View1

by Rick MacPherson with Kreg Ettenger

I am a coral reef scientist, and now find myself at the intersection of science and policy reform. It is an interesting place to be. After spending a lifetime counting parrotfish, I am now counting votes and policymakers. It has brought me into a different aspect of the work that I do, which, over my lifetime, has focused on the intersection between marine protected area (MPA) effectiveness and marine tourism. I believe there is a strong overlap.

I was born in 1963, on another planet. At that time, the atmospheric CO2 concentrations were about 321 parts per million (ppm). They are now over 400 ppm. In 1963, we had devastating hurricanes occurring at a frequency of roughly one every hundred years. We now have them every other year, or so it seems. Caribbean live coral cover in 1963 was near 60 percent, on average. Our live coral cover average right now is between 15 and 18 percent (see Image 2.2.1). You could see sharks on 100 percent of dives in 1963. I challenge you to see sharks in most Caribbean destinations now. Around the world, coastal fishing communities were thriving in 1963. Now, many are just tourist attractions or ghost towns. So, it really is a different planet than just five decades ago.

Image 2.2.1 A dead coral reef3

I learned to dive when I was 10, so for over 40 years now, I have been diving. I have a personal data set of seeing coral reefs for those four decades. That’s why, when I come up from a typical dive today and hear all of the folks on the boat exclaiming, “Wow, that was a great dive,” I wonder, did we dive the same reef? Because I didn’t see any fish, the water was turbid, and the reef had less than 10 percent live coral cover. The baseline has shifted, as Jeremy Jackson and others have pointed out.2 If we have no benchmark for what it used to look like, we begin to think that what we are seeing today is normal.

Coral reefs are in serious trouble. I want to emphasize, however, that MPAs work; that reef resilience can be strengthened over time; that marine recreation providers are ideal partners for MPAs; and that there are tools for marine recreation and MPAs to build resilience. Even though it might seem grim, there is hope.

Tourist Expectations and Marine Protected Areas

Studies have shown that when tourists select a dive destination, they want to see large fish, sharks, rays, and turtles; they want diverse, colorful, healthy coral; and they want good water quality and visibility.4 So tourists are looking for the very things that many coral reefs have lost. Researchers have also looked at what tourists think about protection measures, including limiting tourist activities within certain areas. They have found that tourists are willing to accept restrictions on their access and conduct if those restrictions are part of a conservation effort. So when I hear things such as, “Well, you know, the tourists don’t want to be told what to do or where to go,” that does not hold up, according to the evidence.

As a response, the conservation community has explored the concept of marine protected areas (MPAs). These are not new. Terrestrial protected areas, such as national parks, have existed for a long time, and MPAs have been employed for at least a few decades. They go by many names: marine managed areas (MMAs), locally managed marine areas (LMMAs), marine parks, sanctuaries, monuments, reserves, and so on. Whatever you call them, the science says MPAs work. They do not work just by legislative protection, however. They take management, which is labor, and they take resources to pay people, as well as for materials. So just stamping something as an MPA is not a solution; it also takes work.

There is a spectrum of how much government is involved in an MPA. If you do not want too much government involvement, then an LMMA might fit your need. If you think you need strong government buy-in and support, a legislated MPA might be what you want. There is also a continuum in terms of protection. MPAs can be mixed use, limited take, no take, or no access. The Galapagos have examples of the last category; you just cannot go to some of the islands. Palau also has a set of islands that are off-limits completely. Most protected areas try to at least restrict extractive practices, including commercial fishing and even sport or subsistence fishing.

MPAs used to be created based on what we might consider normal tourism criteria. For instance, is the site accessible? Is there clear water? Is it scenic and safe? Are there lots of pretty fish for people to see? If those are your criteria, then you draw lines on a map that enclose an area and you create your MPA, and we are all happy. But what happens if criteria have to change in response to climate change threats? Then, we start looking at a different set of criteria. Is there good water quality? Are there many different types of coral? Does the coral have particular resistance to bleaching? Is there good survival and strong recovery after events? Is there local capacity for good management? Again, MPAs do not manage themselves.

MPAs, Climate Change, and Resilience

Coral reef resilience refers to their ability to resist stresses brought on by climate change or other factors, and also the quickness with which they can recover. There are different kinds of resilience. There’s biological resilience, meaning does the system recover, does it have life, does it have high coral cover, high biodiversity, low disease, and broad size range? Can it last through a bleaching event (see Image 2.2.2) or a thermal stress event? Then, there is social resilience, which is as important to consider as biological resilience. Do the communities that rely upon reefs have a diversity of local resources? Are they getting protein from places other than the ocean? Can they generate revenue from something other than coral reefs? Are they able to self-organize and self-govern? Does the community have the capacity to learn and adapt, and to achieve financial sustainability? We need to factor all these things into our understanding of resilience.

Image 2.2.2 A NOAA diver examines a reef after a coral bleaching event in St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands5

Over the past decade, we have begun to reevaluate our existing suite of MPAs throughout the Caribbean, and the world, to include more climate change resilience criteria. One example from the Caribbean is Roatán, an island in the Bay of Honduras between Útila and Guanaja. Roatán has a zoned no-take MPA. Interestingly, about a decade ago, we discovered a strand of healthy Acropora cervicornis, an endangered species of staghorn coral, thriving in an area it should not have been. This was outside the MPA, in a place where cruise ships dock on the island. We built a case that this reef should be included within the protected area, and an effort was launched to reevaluate the MPA’s boundaries. Eventually, the lines got extended to include this new area, called Cordelia Bank, within the no-take zone. That is just one example of adaptation—being able to reevaluate lines on the map—because we cannot just assume that protected areas remain static in a changing situation.

Partnerships with the Marine Tourism Industry

Management needs, labor costs, and materials often make it difficult to achieve MPA goals. Where can we find more hands, more eyes, more support? Marine recreation and tourism providers can make great partners. Tourism providers, particularly the diving community, often have detailed knowledge of high-priority areas, unique features, and even rare species. Divers have been shown to be able to perceive low levels of reef damage even before the scientific community characterizes it. Providers also have relationships with local communities, who can assist in biophysical work, including monitoring. And recreation providers host a captive and interested audience who can then spread the word about climate change. For marine recreation providers, healthy reefs mean healthy businesses.

One of the best examples of a marriage between a protected area, a tourism business, and a local community is the Shark Reef Marine Reserve (SRMR) in Fiji. SRMR was created in 2004 as a protected shark sanctuary.6 The reefs were dying, and the local community was not deriving protein from them anymore. So an operator came in to help establish this MPA. He began feeding sharks to be able to create an attracted dive, meaning that you dive with sharks and the sharks are fed to aggregate them (see Image 2.2.3). Revenue generated from this shark dive was used to pay fishermen not to fish in a no-take zone of the reef. It gave a decade of recovery to the MPA, which allowed live coral cover to come back and the fish to get larger. It also had a reserve effect, which means fish were able to reproduce without being caught, and the surplus started to spill over outside of the MPA. Fishermen were, perhaps not surprisingly, finding greater catch in the areas where they continued to fish. In addition, scientific research is now showing a strong link between healthy shark populations and healthy coral reefs. Protecting sharks apparently protects reefs by controlling populations of herbivorous fish that can damage reefs by overgrazing.7

Image 2.2.3 Shark monitoring, NOAA8

Following these successes, the SRMR dive operator began working on a mangrove replantation effort with the village that benefited traditional resource owners. In addition to their considerable value as wildlife habitat and shoreline protectors, mangroves act as a carbon sink, absorbing CO2from the environment. As a result, local businesses that are partnering with SRMR are not just carbon neutral, they are carbon negative. All in all, the Shark Reef Marine Reserve is one of the best success stories in marine conservation, with tourism providers and local fishing communities working together to protect coral reefs and marine and coastal ecosystems.

Conclusion

Even though the perils of our time might be unprecedented, so are the opportunities in front of us. There is great potential for linking MPAs and marine tourism to protect vital resources such as coral reefs in the face of climate change. The recreational diving industry, including our largest lobbying organization, the Diving Equipment & Marketing Association, must speak with one voice on this issue. We must all work to forge alliances with local communities, conservation organizations, and marine scientists to respond to the growing threats posed by climate change. And we must support MPAs as a way of helping coral reefs to be more resilient, ensuring that they can provide food for communities and attractions for divers for generations to come.

Notes

1. This case study was prepared by the second listed author from a presentation given by the lead author at the session “Marine Recreation & MPAs: Fishing, Diving, Surfing,” at CREST’s Innovators Think Tank on Climate Change & Coastal Tourism, July 22–24, 2015, Punta Cana, Dominican Republic. The original presentation, with extensive photos, is available at: http://www.innovators2015.com/presentations/MacPhersonDRinnovators.pdf

2. Nancy Knowlton and Jeremy B. Jackson. (2008). “Shifting Baselines, Local Impacts, and Global Change on Coral Reefs.” PLOS Biology. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0060054

3. Image Source: David Burdick, NOAA. Creative Commons.

4. Linwood H. Pendleton. (1994). “Environmental Quality and Recreation Demand in a Caribbean Coral Reef.” Coastal Management, 22(4). http://dx.doi.org.prxy4.ursus.maine.edu/10.1080/08920759409362246

5. Image Source: NOAA. Creative Commons.

6. Juerg M. Brunnschweiler. (2010). “The Shark Reef Marine Reserve: A Marine Tourism Project in Fiji Involving Local Communities.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(1), 29–42. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09669580903071987

7. Jonathan L. Ruppert, Michael J. Travers, Luke L. Smith, Marie-Josée Fortin, and Mark G. Meekan. (2013). “Caught in the Middle: Combined Impacts of Shark Removal and Coral Loss on the Fish Communities of Coral Reefs.” PLOS One. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0074648

8. Image Source: Kevin Lino, NOAA/NMFS/PIFSC/ESD. Creative Commons.

Sport Fishing and Diving at Turneffe Atoll, Belize: Sustaining Resources through Marine Recreation1

by Martha Honey and Kreg Ettenger

Introduction

Sport fishing in marine environments is sometimes viewed as an extractive activity with negative effects on local marine life and habitats. Done improperly, with poor management practices and a lack of control over where fishers go and what they do, it can be just that. But if measures are taken to protect the fisheries themselves, as well as the critical habitats that support them, sport fishing can generate substantial local and regional tourism revenue, create awareness about climate change and other environmental issues, and motivate local residents to protect and manage resources in more sustainable ways.

At Turneffe Atoll, one of Belize’s three offshore atolls,2 sport fishing is an important component in marine tourism and recreation activities. Currently, it ranks second only to diving and snorkeling in terms of its overall contribution to Turneffe’s tourism economy, generating millions of dollars each year and helping to employ many local residents. Rather than leading to the overuse and exploitation of local fisheries, the careful catch-and-release methods used at Turneffe Atoll actually help to protect these resources by providing a significant international demand for the tarpon, bonefish, permit, and other finfish that populate the atoll’s reefs, flats,3 and lagoons. This demand helps drive a tourism industry that supports hundreds of local residents who work not only as guides, but also in local resorts and other tourism businesses.

In this case study, we consider how sport fishing can be a component of sustainable marine tourism in places such as Turneffe Atoll and elsewhere in the Caribbean. Drawing upon a larger study that was done by the Center for Responsible Travel for the Turneffe Atoll Trust, we use data from site visits, interviews, and previous studies to show how important this activity is economically, and to argue that it is also highly sustainable from a biological perspective, especially when compared to commercial fishing and other extractive activities.

An Overview of Turneffe Atoll

Located 25 miles (40 km) east of Belize City, Turneffe Atoll is a discrete group of cayes4 surrounded by its own living coral reef. Approximately 30 miles (48 km) long and 10 miles (16 km) wide, Turneffe is the largest and most biologically diverse coral atoll in this hemisphere (see Image 2.3.1). The atoll’s land and seascape consist of a network of highly productive flats, creeks, and lagoons dotted by mangroves and seagrass beds. Its shallows serve as important breeding areas for a wide range of fish species, crocodiles, lobster, conch, and other invertebrates. It also includes at least three significant fish spawning aggregation sites. As the largest of the offshore atolls lying to the east of Belize’s coastal shelf, Turneffe is considered to be an integral part of Belize’s reef system, as well as a global ecological hotspot for marine biodiversity. It supports a number of threatened and endangered species, including the American saltwater crocodile, Antillean manatee, and several species of sea turtles. The atoll also supports some of the last remaining littoral forests (those occurring along coastlines or on islands) in Belize.

Image 2.3.1 Map of Turneffe Atoll5

In addition to its wealth of biodiversity, Turneffe Atoll has significant economic value to Belize.6 Using 2010 data, Turneffe’s economic contribution to Belize was estimated to be around US$62 million per year, including US$38 million in shoreline protection from tropical storms; US$23.5 million in tourism revenue; and US$500,000 for commercial fishing. It has historically been a substantial contributor to the commercial harvest of conch, lobster, and finfish in Belize. Turneffe’s commercial fishing experienced a sharp decline over the decade prior to 2010, however, leading to increased pressure to develop other economic activities. Between 2004 and 2009, sales of Turneffe lobster tails to Belize’s fishing cooperatives declined by over 70 percent, while the number of conch sold through cooperatives declined over 60 percent. According to local fishermen, a number of things have contributed to these declines, including illegal harvesting practices.7

Tourism and Development Pressure

With the decline of commercial fishing, tourism has offered an important alternative source of income for local fishermen, who work mainly as guides with tourism businesses (see Image 2.3.2). The atoll is known worldwide as a premier sport fishing and scuba diving destination, as well as a growing center for marine research. Tourism is now the leading economic activity on Turneffe Atoll, generating an estimated US$19 million annually in total direct expenditures.8 When value added or multiplier effects are used, the total economic effect of tourism in Turneffe is close to US$23.5 million per year. Turneffe’s tax revenue from tourists averages US$3.4 million annually. One study found that tourism at Turneffe Atoll supported 1,220 full-time jobs, generating US$14.6 million in personal income to workers employed in tourism and associated industries.9

Image 2.3.2 Turneffe Flats Resort Atoll Adventure Guide Abel Coe teaches visitors about local marine life10

With the growth in tourism at Turneffe, development pressure is now increasing, threatening the atoll’s ecosystems and marine and coastal resources. Over the last decade, land ownership on Turneffe has shifted dramatically. In 2000, nearly all land at Turneffe was government-owned; by 2011, 23 percent was privately owned. Only a small percentage of the 190 privately owned parcels have been cleared or developed to date. Six sites, totaling around 200 acres, have been developed for tourism: three all-inclusive sport fishing and dive resorts, two educational research stations, and one restaurant and resort. Another four properties, totaling 25 acres, have been fully or partially cleared for residential development.

Distance and inaccessibility have helped to protect Turneffe from the fast-paced and often chaotic overdevelopment that has occurred elsewhere in Belize’s coastal areas. Nevertheless, Turneffe has already experienced some destructive and inappropriate development, and this is likely to increase as more of its land becomes privately owned, and as access is increased with more airstrips and faster boat linkages to the mainland. As the Turneffe Atoll Coastal Advisory Committee’s 2011 Development Guidelines state, in order to “sustain Turneffe Atoll’s sensitive and valuable terrestrial and marine environments,” its tourism industry must be “managed sustainably by facilitating low-impact, nature-based tourism capitalizing on its unique natural assets.”11

In 2012, partly in response to increased pressure from tourism activities, the Belize government created the Turneffe Atoll Marine Reserve. Until then, Turneffe Atoll had been the only atoll in the Belize Barrier Reef System with no significant protection or directed management. Studies at Turneffe, including the one on which this case study is based, have shown that diving, sport fishing, and other forms of marine-based tourism benefit from successful marine reserves and can help to protect them. In contrast, large-scale commercial fishing and large-scale or poorly planned resort development tend to damage fragile atoll environments, including corals, mangroves, and other marine habitats.

In addition to threats from overdevelopment and resource exploitation, Turneffe Atoll is at risk from the various effects of climate change in this region. It also plays a key role in helping to mitigate these effects, as the Turneffe Flats Resorts website explains:

Approximately 90 percent of Turneffe is low lying land covered by mangroves, making it particularly sensitive to sea [level] rise. At the same time, Turneffe’s ecosystems mitigate many of the dire effects of climate change. A major economic function of Turneffe Atoll, for instance, is the protection of Belize City from hurricanes, which economists value at more than 90 million dollars annually. Additionally, mangroves produce significant carbon offsets and essential fisheries habitat. Turneffe is, therefore, threatened by climate change but also offers environmental assets to help our planet adapt to these changes.12

Diving, Sport Fishing, and Ecotourism

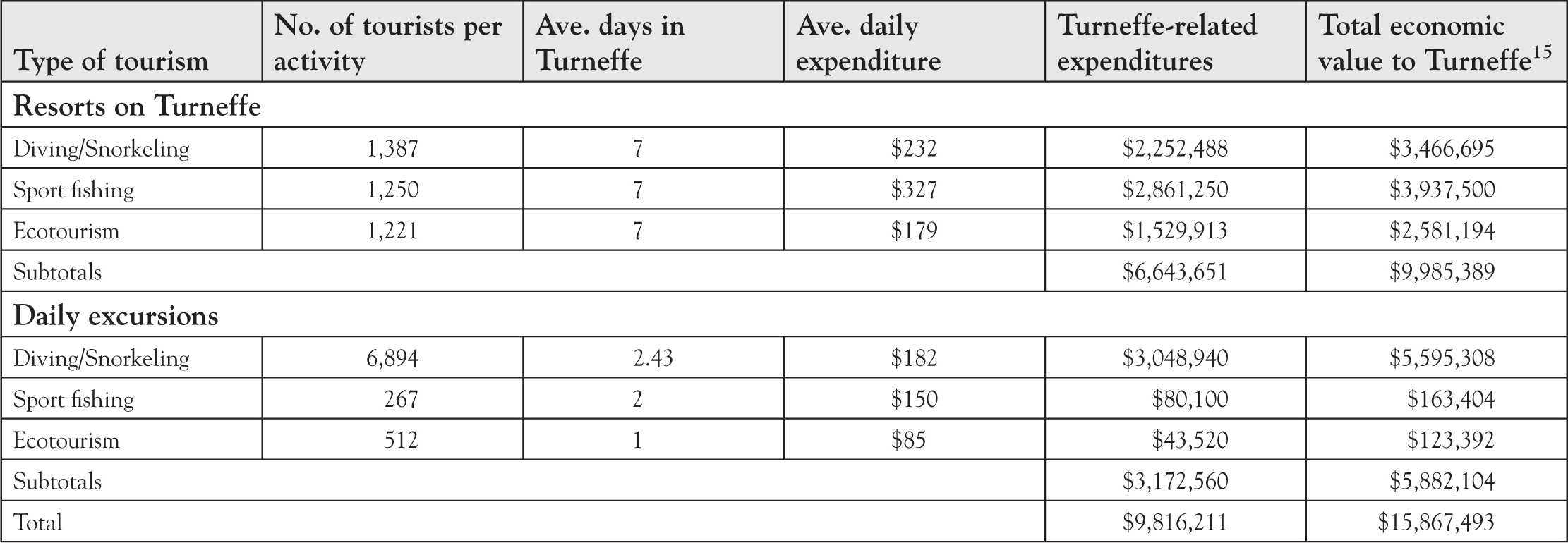

Turneffe Atoll has become a world-renowned destination for marine tourism, including scuba diving and sport fishing, as well as wildlife viewing and other forms of ecotourism. Two main types of tourism businesses are found on Turneffe Atoll: all-inclusive resorts, which provide tourism activities as part of a package price, and businesses not based at Turneffe that provide daily excursions to the atoll. Tourists stay at one of the three resorts currently operating on the atoll, or come on day trips from Belize City, San Pedro, Caye Caulker, and Placentia, or from cruise ships in port. In a detailed study, Anthony Fedler identified 68 businesses, including hotels, resorts, dive shops, live-aboard boats, research facilities, and tour operators, that offered tourism services at Turneffe. Based on data from 49 businesses that completed his survey, Fedler calculated the economic value of some 11,500 tourists who visited Turneffe in 2010 for diving, sport fishing, and other ecotourism activities.13 Table 2.1 summarizes these results.

Table 2.1 Tourist numbers & expenditures at Turneffe Atoll, 2010 (in US$)14

As evident from these statistics, diving and snorkeling are the predominant marine tourism activities on Turneffe Atoll, contributing more than US$9 million to the local economy in 2010. Sport fishing is second, contributing over US$4 million per year to Turneffe’s economy. Importantly, recreational fishing generates more revenue per tourist than diving due to the fact that most sport fishers stay at local resorts for multiple days. Other ecotourism activities, such as wildlife viewing and nature tourism, contributed another US$2.7 million. These three activities combined generated nearly US$10 million in direct expenditures, and almost US$16 million in total economic value, in 2010. This means that roughly two-thirds of the total tourism revenue at Turneffe Atoll comes from tourists who engage in these three primary activities, and in particular, from those who come to the atoll for diving, snorkeling, and sport fishing.

Turneffe offers catch-and-release sport fishing for bonefish (Albula spp.), Atlantic tarpon (Megalops atlanticus), and permit (Trachinotus falcatus) (see Image 2.3.3). It has been recognized by experts as one of the world’s seven best bonefish destinations, and one of the 10 best permit fishing destinations.16 Catch-and-release fishing (where captured fish are immediately returned alive to the sea) plays an essential role in ensuring the sustainability of this activity, as well as in preserving local fish stocks. In 2009, Belize passed landmark sport fishing legislation, becoming the first country in the world to mandate that all bonefish, tarpon, and permit be released.17 As Alex Anderson and Craig Hayes explain, however, this type of sustainable fishing has actually been practiced at Turneffe for much longer:

Image 2.3.3 A permit fish is released during a Turneffe Flats sport fishing trip19

Catch-and-release sport fishing has been the standard practice at Turneffe Atoll for three decades. Over this period, the health of Turneffe’s sport fishery has not only been sustained, it has improved. Sport fish stocks have increased, as has average fish size. This would appear to substantiate that catch-and-release, as it is practiced in Belize, has successfully established a sustainable sport fishery.18

Relative Impacts of Resorts, Day Trips, and Cruise Ships

Turneffe attracts a relatively small number of high-value visitors. The most economically beneficial are those tourists who stay at one of the atoll’s three lodges, and whose visits last a week or more on average. These are followed by tourists who visit Turneffe with tour boats and spend, on average, just over two days diving or fishing at sites within the atoll. Least beneficial are cruise ship passengers, who spend less than half a day diving or snorkeling at Turneffe, and whose contribution to the local economy is minimal. Turneffe’s best option in terms of economic benefits, therefore, as well as for environmental and social sustainability, is to carefully expand both the overnight capacity of the atoll and the number of day visitors brought in from elsewhere in Belize.

The majority of sport fishing and ecotourism at Turneffe is done by guests at resorts on the atoll, rather than through day visits from other locations. In contrast, for diving and snorkeling, nearly five times more tourists participate in such activities via daily excursions than from resorts. Our findings show that for all three types of activities—diving, sport fishing, and ecotourism—tourists staying in a Turneffe-based resort generate more money for Belize’s economy than do those on day excursions. Thus, tourism proponents should explore ways to sustainably increase Turneffe-based accommodations while insuring protection of the atoll’s environment. The atoll’s carrying capacity is limited, and tourism needs to be done in ways that do not overwhelm the atoll’s fragile environment.

In comparison to the significant economic value of sport fishing and diving to the Turneffe economy, cruise tourism contributes rather little, even when cruise ship passengers engage in marine recreation activities. Fedler estimated that in 2010, 1,300 cruise ship passengers took part in diving and snorkeling tours on Turneffe Atoll. Based on our own calculations, and considering the economic leakage that occurs when cruise ship passengers book activities directly through cruise lines, the revenue generated for the Belize economy was somewhere between US$110,000 and US$120,000; the amount actually flowing into Turneffe’s economy was likely a fraction of this. In contrast, scuba diving offered by resorts in Turneffe generated US$3.5 million in 2010, or roughly 29 times as much revenue, for virtually the same number of divers.

In terms of environmental impacts, all forms of marine tourism at Turneffe, whether based on resorts, day trips, or cruise ships, have their share. The impacts of cruise ships on local, regional, and global environments are described in Chapter 4 of this volume. Day trips, while having fewer direct environmental impacts on local communities and resources, can have significant impacts in terms of their carbon footprint; fishing boats from the Belizean mainland have to travel 25 miles (40 km) or more to reach Turneffe. Resorts, for their part, can be sustainably built and operated, but can also do significant damage to mangroves, dunes, and other coastal habitats, and can place enormous burdens on fresh water and other limited resources. At Turneffe Atoll, there are examples of both sustainably managed resorts and those that are doing serious harm to the environment.

One example of the latter is a new resort called the Belize Dive Haven Resort and Marina by Sir Hakimi—by far, the largest resort to date at Turneffe (see Image 2.3.4). Promotional material for the resort states, “This exclusive, private island already boasts a 300-foot pier with a 60’ × 70’ restaurant overlooking the clear, blue Caribbean Sea, and a 500’ dock and dredged bay to accommodate large yachts.”20 Nearly everything about the project seems inappropriate for an environmentally fragile atoll. When completed, the facility will include a 96-room hotel, an airstrip, condos, and a supermarket. An April 2012 visit to the construction site revealed not only extensive dredging of sand from the shallow waters around the caye, but an enormous (200 foot) swimming pool. The concrete shells of two buildings containing a total of 48 rooms had already been built, and foundations for two more were in place. By December 2016, while the infrastructure had expanded considerably, the resort was still not open.21

Image 2.3.4 Sir Hakimi’s Belize Dive Haven under construction in 201222

Some resorts, including Turneffe Flats Resort and Turneffe Island Resort, are designed on a much more appropriate scale and are run using sustainable management practices, showing that not all resorts on Turneffe need to destroy the environments on which they depend. Based on CREST researchers’ observations and interviews, there appears to be a need for improved environmental assessment prior to building tourism facilities and more oversight of construction activities once they begin.

Ensuring Sustainable, High-Value Tourism at Turneffe Atoll

The future of tourism in Turneffe is being shaped by government policy, Belize’s international tourism image, and the realities of the atoll itself, as well as by trends in international tourism. Turneffe has a successful and largely sustainable tourism industry based on three non-extractive activities: catch-and-release sport fishing, diving, and ecotourism. There is potential for each of these activities, including fishing, to be gradually and carefully expanded. However, the atoll faces threats from a lack of control over tourism construction and other development. Creation of the new marine reserve is a major step toward sustainable development, but it must be accompanied with clear enforcement of Belize’s regulations for tourism development, as well as adherence to internationally recognized best practices for sustainable tourism.

Equally important is determining how much Turneffe’s tourism sector can expand and still be sustainable. Based on our own analysis and the opinions of local experts, the total number of operating resorts should probably not exceed half a dozen. Several all-inclusive resorts could be complemented with a small number of more basic overnight guesthouses. According to the 2011 Management Guidelines, “Some traditional fishermen have expressed a desire to develop their fishing camps into small guest houses offering the eco-cultural experience of the fishermen.” The guidelines go on to recommend that zoning should provide local fishers with the option of developing such guest houses, thereby “promoting opportunities for traditional users to benefit from tourism.”23 This will be increasingly important if commercial fishing resources, mainly lobster and conch, continue to decline.

The most suitable types of tourism for fragile island and atoll ecosystems such as Turneffe are small-scale, low-impact resorts that specialize in non-consumptive fishing, diving, snorkeling, and other marine and land-based activities. These ecolodges can, and should, be built in accordance with sustainability guidelines, such as those created by leading certifying organizations. Another opportunity for low-impact economic development on the atoll is educational and volunteer tourism run through the atoll’s current research centers or in conjunction with ecolodges. Larger, more mass-market-oriented hotels and resorts are wholly inappropriate for Turneffe Atoll.

Clearly, the establishment of the new Turneffe Atoll Marine Reserve is a critical step in the right direction in terms of ensuring the sustainable development and longevity of both commercial fishing and marine-based tourism. The marine reserve will attract the types of environmentally and socially conscious tourists that are most appropriate for Turneffe (see Image 2.3.5). The marine reserve by itself, however, will not “save” Turneffe. It must be accompanied by stronger standards for sustainable construction and operation of resorts, research facilities, private homes, and other developments to conform to existing regulations in Belize and the growing knowledge of international best practices. Only through protecting the atoll’s marine and terrestrial ecosystems will Turneffe continue to grow as an attractive destination for high-value tourism.

Image 2.3.5 Divers at Turneffe Atoll view a barracuda24

Conclusion

Turneffe Atoll’s non-extractive, small-scale marine tourism has demonstrated its compatibility with sustainable management of local fisheries and other marine resources. This type of tourism, which includes sport fishing, diving, and snorkeling, depends on a healthy marine environment. Turneffe’s world-renowned catch-and-release sport fishing is causing negligible mortality and has led to an increase in stocks of bone, tarpon, and permit. These species are not of commercial value, and in the main, sport fishing takes places in different locations than commercial fishing. This has enabled sport and commercial fishing to coexist, rather than compete with each another. In addition, with the decline of commercial fish stocks, tourism has provided alternative employment for dozens of commercial fishermen.

To respond to climate change, the decline of commercial fishing, and other pressures, Turneffe needs to gradually grow its market for high-value tourism that emphasizes environmental stewardship, good jobs, and sustainable use of local resources, all based on relatively modest numbers of visitors. The emphasis should be on controlled and sustainable growth, and on strengthening existing facilities to improve their environmental and social practices. Adoption of an internationally recognized, national certification program for accommodations (as well as for other tourism facilities, including boats and beaches) is important in ensuring long-term protection of the atoll. In terms of day visitors, emphasis should be on increasing the numbers of visitors from Belize City and other parts of the country, rather than from cruise tourism, which provides the least economic benefit to Turneffe.

Fortunately, the type of tourism that is most suitable for and beneficial to Turneffe Atoll constitutes a significant and growing sector of the traveling public. Broadly stated, these are experiential or conscientious travelers who seek vacations that are both enjoyable and educational, who want to connect with nature and have authentic experiences, and who are concerned about the impacts of their travels on the environment and host communities. The new MPA enhances Turneffe Atoll’s appeal to these discerning travelers and helps ensure the longevity and sustainability of the destination and its main economic sector, marine-based tourism.

Notes

1. This case study is largely based on the report, Turneffe Atoll, Belize: Balancing Sustainable Tourism & Commercial Fishing in a Marine Protected Area (MPA), prepared by the Center for Responsible Travel (CREST) for the Turneffe Atoll Trust, January 2013. The primary author of that report was CREST Co-Director Martha Honey, with assistance from staff members Catherine Ardagh, Kyle Hook, and Naomi Garner. Findings were based on a site visit and interviews in Belize City and at Turneffe Atoll, along with a review of multiple primary documents, academic studies, published articles, and websites. CREST would like to thank the Turneffe Atoll Trust for commissioning and financing this study. Craig Hayes, the Trust’s Board Chairman and owner of Turneffe Flats Resort, provided background materials, organized the site visit and interviews in April 2012, and reviewed the final draft. The report was also reviewed by CREST Co-Director William H. Durham at Stanford University.

2. An atoll is “a ring-shaped coral reef, island, or series of islets [often surrounding] a body of water called a lagoon.” National Geographic Society. http://nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/atoll/

3. Reef “flats” have been described as “expansive shallow areas with adjacent tidal creeks [forming] a complex habitat mosaic comprised of mangroves, sea grass, benthic algae, sand, coral rubble, limestone, and mud bottom that supports an inherently diverse community” of marine life. J. Aaron Adams and Steven Cooke. (2015). “Advancing the Science and Management of Flats Fisheries for Bonefish, Tarpon, and Permit.” Environmental Biology of Fishes, 98(11), 2123–31.

4. A cay or caye is a small, low-elevation, sandy island on the surface of a coral reef. They occur in tropical environments throughout the Caribbean, Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans. “Cay.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cay

5. Image Source: Turneffe Atoll Coastal Advisory Committee. Used with permission by the Center for Responsible Travel (CREST) from the report, Turneffe Atoll, Belize: Balancing Sustainable Tourism & Commercial Fishing in a Marine Protected Area (MPA), prepared by the Center for Responsible Travel (CREST) for the Turneffe Atoll Trust. (January 2013).

6. Anthony Fedler. (2011). The Economic Value of Turneffe Atoll: Full Report. Human Dimensions Consulting.

7. Ibid, 15–16.

8. Martha Honey, Catherine Ardagh, Kyle Hook, Naomi Garner. (January 2013). Turneffe Atoll, Belize: Balancing Sustainable Tourism & Commercial Fishing in a Marine Protected Area (MPA). Prepared by the Center for Responsible Travel (CREST) for the Turneffe Atoll Trust. http://responsibletravel.org/docs/Turneffe%20Atoll%20Full%20Report.pdf

9. Anthony Fedler. (2011). Op cit.

10. Image Source: Turneffe Flats Resort. Photo credit Pablo Negri.

11. Turneffe Atoll Coastal Advisory Committee. (2011). Turneffe Atoll Coastal Zone Management Guidelines 2011. Belize City, Belize: Coastal Zone Management Authority and Institute.

12. Turneffe Flats. (2016). “Threats.” http://www.tflats.com/threats/

13. No attempt was made to estimate tourism revenue from non-responding businesses; therefore, these statistics underestimate the full extent of tourism benefits from Turneffe Atoll.

14. Table Source: Center for Responsible Travel (CREST) from the report, Turneffe Atoll, Belize: Balancing Sustainable Tourism & Commercial Fishing in a Marine Protected Area (MPA), prepared by the Center for Responsible Travel (CREST) for the Turneffe Atoll Trust. (January 2013).

15. Total economic value includes the spinoff effects from spending by those employed in the tourism industry, the value of ancillary businesses, and other indirect economic benefits.

16. Turneffe Atoll Coastal Advisory Committee. (2011). Op cit., 1.

17. Ambergris Today. (February 12, 2009). “Belize Passes Landmark Catch and Release Fishing Legislation.” Press Release. Belize City, Belize. http://ambergriscaye.com/forum/ubbthreads.php/topics/324468/belize-passes-landmark-catch-and-release-law.html

18. Alex Anderson and Craig Hayes, (2011). “Analysis of Fish Mortality Related to Catch and Release Sport Fishing in Belize.” Unpublished research report. http://www.turneffeatoll.org/tat-action-plan/most-catch-release-mortality-at-turneffe

19. Image Source: Turneffe Flats Resort. Photo credit Terry Gunn.

20. Belize Dive Haven Resort & Marina. http://belizedivehaven.com/

21. As of December 12, 2016, the resort’s website was not yet accepting bookings, but visitors could sign up to receive email updates on its grand opening. http://belizedivehaven.com/

22. Image Source: Center for Responsible Travel (CREST).

23. Turneffe Atoll Coastal Advisory Committee. (2011). Turneffe Atoll Coastal Zone Management Guidelines 2011. Coastal Zone Management Authority and Institute: Belize City.