Drivers of Influencer Marketing

Launching a New Brand Using Influencers

Can a new brand build its growth and build its brand image using primarily social media influencers (SMI)? New brands come and go and often have a tough time unseating the category leaders, especially in extremely competitive spaces such as beauty and skincare. However, indi skincare brand Tula (which means “balance” in Sanskrit) has been able to increase awareness and sales primarily through building their marketing foundation on authentic social media influencers and paid social advertising boosts. In 2020, the brand—which is based on the intersection of wellness and beauty—garnered $56 million in earned media value. The skincare brand unveiled its #EmbraceYourSkin campaign in October 2020 and reached more than 120 million consumers and recorded more than one million engagements through the end of the year.

Tula (www.tula.com) is a “digitally native and social media first” brand with a majority of its revenue coming from direct to consumers (DTC) with three times revenue growth in the past three years. The brand was first launched in 2014 by Dr. Roshini Raj, a gastroenterologist and internist who focuses on probiotics and superfoods in her practice found the same benefits for skincare. She launched Tula with cofounders Ken Landis, cofounder of Bobbi Brown cosmetics, and Dan Reich, a tech entrepreneur, to maximize the benefits of natural ingredients for skincare for all types of skin issues. In 2017, the company garnered significant capital infusion to scale revenue and growth. In the past two years, Tula has seen several successful product launches. In April 2020, Tula launched a gel sunscreen that was the most requested products from customers and was one of the most successful product launches for them. In October 2020, Tula and gymnast Shawn Johnson partnered in a limited edition So Pumpkin exfoliating sugar scrub, which sold within hours of its launch. As a result of this launch, Tula earned $6.1 million in earned media value in October alone, ranking number two among skincare brands.

Perhaps, part of it was timing. When the pandemic hit, customers found themselves increasingly concerned about health and wellness (and more people embraced the “no makeup” look since everyone was home). As part of the #EmbraceYourSkin campaign, Tula tapped social media influencers Tess Holliday, Tennille Murphy, Nyma Tang, Chizi Duru, and Weylie Hoang to create kits to address specific skin issues. Interestingly, this stable of influencers was the result of an intentional effort where Tula recruited influencers based on a revenue sharing model similar to Avon. As part of the campaign, influencers interacted with followers using video tutorials and engaging in conversations about skincare. Conversations happened both on Tula’s social channels and within influencers’ social channels. CEO Savannah Sachs said, “We’re proud to shine a spotlight on the work and impact that these women have had in the industry, specifically for ageless and natural beauty, size representation and skin tone diversity.”1

Why are influencers so effective for Tula? One could argue that Tula was effective at getting attention. Tula was able to capture the attention of enough customers who then made purchases. However, as Amanda Russell argues in her book The Influencer Code, “attention is currency, attention is not success. The world is largely confusing attention with influence. Attention without trust is simply noise.”2 It could also be because consumers don’t really want to have relationships with brands; rather they are more interested in people. According to Neal Shaffer, author of The Age of Influence, “Harnessing true people power—and that is what the voices of influencers are—requires a different approach to how brands traditionally spread their message. It is a shift in communicating and interacting with your customers and audience. It’s about user generated content. It’s about community. It’s about relationships. It’s about engagement.”3 As influencer marketing—boosted by social media platforms and technology—increasingly becomes a larger part of a brand’s marketing budget, it is important to understand more about it what influencer marketing is, why it works for brands and audiences, and how it works most effectively. To do that, let’s start at the foundation.

Social influence is the ways that people change their attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors based on the information and actions of others in order for people to meet the demands of a social environment. Social influence is the foundation for influencer marketing, but social influence is more than just popularity, or “going viral” or being famous.4 It is a natural process used by other people and businesses to influence a person’s attitude and/ or behavior. Social influence drives how effective celebrity endorsers and social media influencers can be in their attempts to persuade others to act (or in the case of marketing—to buy). Social influence can be thought of as the “what” behind influencer marketing. In 1958, psychologist Herbert Kelman identified three broad varieties of social influence (compliance, identification, and internalization). When considering influencer marketing, the conceptualization of identification—when people “wish to establish or maintain a satisfying self-defining relationship to another person or group and he/she adopts the influence because it is associated with the desired relationship”5—is one of the critical concepts. Often, these relationships are with someone who is liked and respected. Additionally, informational social influence involves accepting information or advice from a person who may not have previously been known as a friend or colleague, and this theory also helps us to understand the foundations of influencer marketing. Specifically, it sheds light on how a person (e.g., influencer) who is not known personally to people but who have something (e.g., expertise, trust, or other quality) that is compelling enough for people to follow his/her advice and suggestions can be an effective marketing strategy.

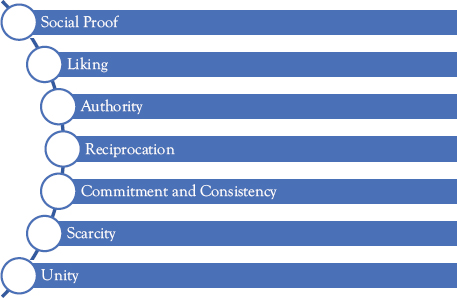

Other related theories also provide a strong foundation for influencer marketing. Psychologist Robert Cialdini6 defined seven principles of persuasion that can contribute to someone’s propensity to be influenced. This can get into the mechanics of how the message is constructed. The seven principles include reciprocation, commitment and consistency, social proof, authority, liking, scarcity, and the newest addition—unity (Figure I.1).

At least three of principles can be useful for understanding influencer marketing. First, social proof applies to the way people decide what is “correct behavior” by examining how others are performing that behavior and using that evidence as a signal. Influencers are particularly good at presenting brands and other information in a way that gives the impression that “everyone is buying it and so should you.” Social proof is particularly important in new situations where people tend to look to others they trust. Generally, social proof is based on experts, celebrities, users, and the wisdom of others that tend to drive influence.7 Second, liking is very simply that people say yes to the requests of people that are liked. This is explained further in Chapter 4, but the idea of being liked is a very powerful tool for influencers and indeed a foundation of their connection with their audiences. While there are several drivers of liking, for influencers, the issues of attractiveness, similarity, and familiarity are important foundations for credibility. In fact, the power of liking or affinity is often overlooked by marketers who see influence as a matter of reach or popularity exclusively.8 Last, authority explains the power of people in recognized authority positions (e.g., doctors and specialists). Authority is a powerful tool for influencers who are trying to use their expertise and legitimate experience when promoting a product. Authority can extend to people who are insiders (those with exclusive access), connectors (those who know everyone and have a large network), and activists (those passionate about a cause or issue).9 Authority is often accompanied by power and title and establishes some type of control. While social influence can be considered the “what” of influencer marketing, and influencers are the “who,” exactly how does messages diffuse from brands and influencers out to consumers?

Figure I.1 Principles of persuasion

While they are useful for marketers wanting to connect to consumers, influencers can only do so much. The goal of influencer marketing is to get people to act on recommendations. But recommendations need to go beyond one-on-one connections. In general, word of mouth (WOM) is described as informal communications directed at other consumers about particular goods or services which can include product-related discussions and shared content online. It includes direct recommendations and mere mentions.10 WOM marketing happens when recommendations from an influencer take on a life of its own and travel through a community gaining earned media, whereby people are engaging with and talking about information and recommendations. The efficacy of WOM marketing really depends on why people are talking and listening—including reasons as varied as acquiring information to social bonding to persuading others.11 WOM marketing is a bit of the Holy Grail for brands. People trust people more than organizations. They trust recommendations from friends and family. These recommendations are incredibly influential. But brands struggle when trying to create the energy around WOM marketing. Brands cannot guarantee that customers will simply mention their products and services on their social media platforms, even if they love the brand. WOM is also tough to scale—getting thousands of people to know about the brand, talk about it, and share it is also truly difficult. So, influencer marketing distributed through social media offers a solution to these challenges around WOM marketing.

Influencer Marketing

The Early Years

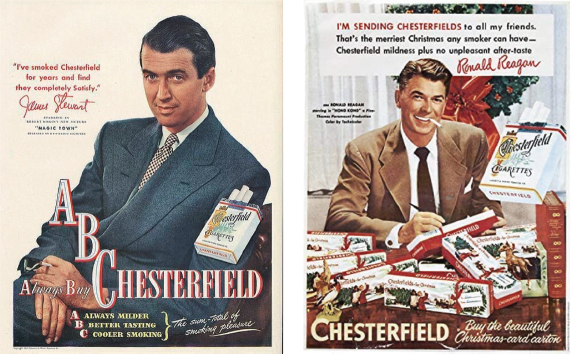

The idea of influencers and their connection to marketing has been around for hundreds of years. Some of the earliest influencers include the Pope and a country’s royalty—the King and Queen given the expectations from Feudal Law that people would do what they said to do. The Industrial Revolution ushered in a whole new era of goods that could be purchased which made marketing and advertising important considerations. In the 1800s, British actress Lillie Langtry was linked to multiple brands and Mark Twain endorsed cigars and tobacco products.12 In the early 1900s, marketers began to tap into the power of celebrities. For example, Murad cigarettes featured Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle in print ads making him one of the first celebrity endorsers. Tobacco companies were early adopters of using celebrities in their marketing as both James Stewart and Ronald Reagan endorsed Chesterfields (Figure I.2). Marlboro cigarettes then created the fictional persona of the “Marlboro Man” who set the image for that brand for years. This was one of the first “fictional” endorsers (later joined by everyone from Tony the Tiger for Frosted Flakes to the Jolly Green Giant).13

But it was not until the 1980s that the concept of celebrity endorsers really took off. Basketball star Michael Jordan was one of the most popular and influential endorsers, and Pepsi Cola built its brand on using celebrities, including the pop singer Michael Jackson. At the same time, there were early forms of what is now known as influencer marketing. I spoke to Ryan Schram, chief operating officers and president of IZEA,14 one of the largest influencer marketing firms. The founders of IZEA saw the early potential of the intersection of social media and endorsers for brands. Schram said that much of influencer marketing had its structural origins in affiliate marketing in the early 1980s. Essentially, affiliate marketing is when a business rewards people or “affiliates” for bringing in new customers. Then, multilevel marketing schemes started to go digital where the original messages were “pass along” e-mail campaigns.

Figure I.2 Early influencers: celebrities

At the same time, versions of social platforms like MySpace allowed users to have a “wall” where they started to create and share content. Most of the content was music—where users copied and pasted clips of music. That was one of the first inklings of the potential of the creator economy. Technology then created live journals, which then became blogs, mostly through the popular Blogger platform (created by Evan Williams and later sold to Google). “Blogger, however, gave people the freedom of starting to combine how to work with a brand and how to create unique content and to start to receive income from that,” said Schram. The number of bloggers continued to increase as people found blogging to be a creative outlet for many people and the number of product categories began to expand.

At the time, an early digital pioneer named Ted Murphy was running a digital agency called MindComet (www.mindcomet.com), and as part of the agency offering, Murphy developed proprietary intellectual property that he licensed and sold to clients. One of the early services was the Blog Star Network, which allowed brands access to mommy bloggers. At the time, mommy bloggers (women who blogged about children and lifestyle issues) were one of the largest content creators. Early blogger campaigns were seen as paid advertising—banner ads on blogs. But this started the process of brands paying for access through goods and services in return for bloggers to write about their business. This was also the first way bloggers were able to monetize their work.15

But the early days were not easy. There were many problems at first simply because brands tried to tightly control content. Brand managers simply thought of paying bloggers as just another form of paid advertising. “As you might imagine, there were so many misfires and gaffes as that was working itself out because some people saw this as—oh well, I am paying these people, therefore, it should be basically an advertorial and they should do what I say and write exactly what I—the client—want,” said Schram.

Remember, at this time, there was no Facebook or Twitter and interestingly, there was a huge backlash about the role of advertising on social media. MindComet was one of the first companies trying to monetize social media (and received a lot of negative push back for it), but Murphy had enough early success to attract venture capital funding in 2005 and 2006 to spin the Blog Star Network into a separate company and rebranded as a company called PayPerPost. “It is credited for being the very first influencer marketing platform, although it was still not called influencer marketing back then and it was openly about paying bloggers to create content for brands,” said Schram. “Industry people, even those who people today see as being the forward innovative social thinkers, were saying ‘oh no, we should never get paid for working with a brand.’ And now that is the entire business model.”

Enter Social Media

By the early 2000s, a new type of celebrity—reality stars—became highly influential (and entertaining). Shows such as MTV’s Real World was an early innovator that led to top franchises like The Bachelor and The Bachelorette, The Real Housewives, Jersey Shore, and Project Runway among others. Keeping up with the Kardashians, launched the careers of the Kardashians and Jenners, who are now some of the top influencers in the social media age.16

Then came the expansion of platforms: Facebook in 2004 and Twitter in 2008. To capitalize on the growth of new platforms, Murphy and MindComet started building out different marketplaces for each of these major platforms (like sponsored tweets for Twitter). Fun fact: PayPerPost (IZEA as it is known now) was the first company using sponsored tweets to pay a little known reality star named Kim Kardashian for a sponsored Tweet.

Murphy then pivoted and rebranded as IZEA which went public in 2011 because larger brands and agencies were doing sponsored social and had increasingly larger budgets. Schram recognized, from his professional background in radio sales, that the most valuable inventory in radio is when an on-air personality (e.g., DJ) opens up to the audience and tells a story about where he went out for dinner. It is not recorded or scripted, but it is effective. “I looked at sponsored social—now influencer marketing—and I said we are doing all of the mediums and we are democratizing this right because it is going from a broadcast mentality—a one to many—to a many to many medium. It also allows the brand to benefit in a different way. It’s not just the implied endorsement … it’s not just the reach and awareness and perhaps engagement, which are all important. It is about content creation,” said Schram.

By the mid-2010s, the popularity of social media was pivotal to launching social media influencers. Some social media influencers are indeed celebrities and reality stars. Others, however, are normal people who have built their networks and their reputation on social media platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube. More about them later. Brands and agencies began to figure out how to merge influencer marketing with traditional marketing. According to Addi McCauley, director client strategy and development at IZEA, “Early on there was a heavy public relations (PR) integration. PR people wanted to put out press packages and wanted to get the word out and it was about a very high top of the funnel awareness play in terms of where it fit into a plan. Then a lot of PR agencies were starting to move into digital to expand revenue streams so they were able to expand offerings beyond getting clients on Good Morning America to being able to help with digital.”17 More pure play digital agencies began to take shape, and then media agencies were also getting into influencer marketing because they viewed influencer marketing as a media play as opposed to a PR initiative. “This has led to influencer marketing being super disjointed across organizations,” McCauley added.

Influencer marketing is relatively new (at least in the form that it is currently being used), and there are several definitions of influencer marketing, from both academic researchers and marketing practitioners. In Chapter 3, there is a discussion on the foundations for influencer marketing definitions from both perspectives. But in order to set the context, let’s define it. Influencer marketing is the strategy of compensating people who are influential in specific areas to create and promote content on social media on behalf of an organization or brand with content that captures the attention and trust of the influencer’s community, thus opening up new opportunities for the organization or brand. There are also several misconceptions about influencer marketing. Influencer marketing is not advertising (although oftentimes paid media is used to boost content). Rather influencer marketing is larger than a simple transaction between the brand and the influencer and the influencer and their audience. It is based on relationships. While most of what I cover here is based on social media, influencer marketing can be much broader. Influencers simply use social media platforms to extend their relationship with their audience. Given that, influencer marketing can take place through live events and other initiatives that are not solely online.18

The (Current) State of the Industry

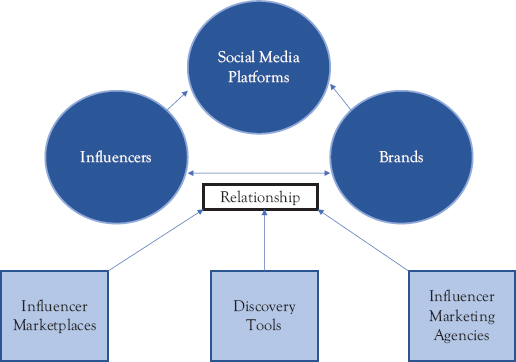

In 2021, the industry has grown—not just in the amount of money that brands spend on influencer marketing but in the number of major and minor players in the influencer marketing ecosystem. In fact, by the end of 2019, there were more than 1,100 platforms and influencer marketing focused agencies operating in the market. To give some context, there were 190 such entities in 2015.19 On each side of the equation are the demand—the brands (large and small)—and the supply—the influencers (well known and not). Social media platforms are the connective tissue—where the influencers build their audiences and where brands build their images. In between there are several intermediaries, which help brands and influencers as well as technology that facilitates campaign development and measurement. Given the nature of the evolution, traditional agencies, media agencies, PR agencies, digital agencies, and of course, influencer marketing agencies are all playing a role depending on the brand’s needs. And many of the entities work together. Technology is playing a more important role than in the past. There’s not a one size fits all approach. “Each of my clients is its own special snowflake in that they are all different,” said Addi McCauley, IZEA.

Let’s examine the ecosystem (Figure I.3).

Social Media Platforms

Social media is a technology centric ecosystem where a diverse set of behaviors, interactions, and exchanges involving interconnected actors—individuals, companies, and organizations—can occur. Social media is now pervasive and culturally relevant.20 The primary social media platforms used for influencer marketing include Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube as the current frontrunners. Pinterest is also making a resurgence given the visual nature of the platform. That said, other social media platforms such as LinkedIn and Facebook also include some influencer marketing campaigns. Clubhouse and Dubsmash are also options. The advantages and disadvantages of the social media platforms are discussed in Chapter 5.

Figure I.3 “Influencer marketing ecosystem”

Influencers

Influencers are people who create and disseminate content to audiences that they have built on social media platforms. Influencers include well-known celebrities, reality stars, and a variety of types of influencers. The advantages and disadvantages of influencers are discussed in Chapter 2.

Brands and Organizations

Brands are businesses that sell products and services to consumers and other businesses. Many of these use marketing and advertising as ways to gain awareness and sales. Some brands develop influencer campaigns in house and some use intermediaries. In most cases, influencer marketing falls to either the brand management team or the digital, social media, and web development teams. In a few cases, it falls to the creative development team. Brands use influencers in a variety of ways, and the mechanics of campaign development are discussed in Chapter 5.

There are several intermediaries that assist in connecting influencers and brands, facilitating relationships between influencers and brands and measuring the effectiveness of campaign efforts.21 It is impossible to develop definitive lines as the industry is undergoing a technological revolution as well as a flurry of acquisitions and mergers. In order to provide tangible examples, I spent some time reviewing IZEA’s ecosystem offerings after talking with Ryan Schram and Addi McCauley. First, there are companies that help brands understand the nature of the conversations happening online. Social media listening tools are designed to know who is talking about a brand online, what they are saying, where they are saying it, and what they are saying about the competition. Social media listening tools are also used to monitor brand reputation. Examples include companies like Meltwater, Brandwatch, and Mention (among many others). IZEA created Brand Graph, which marketers can use to identify and measure brand share of voice, engagement metric benchmarks, category spending estimates, sentiment analysis, and influencers in the category. Essentially, Brand Graph is a content analysis engine that analyzes and aggregates influencer content (www.izea.com). Second, there are tools that assist brands to discover influencers. Many are primarily Instagram centric (for now) and are not based on opt ins from influencers. These allow brands to filter through millions of users to find effective influencers. A few companies include Hypr, Neoreach, and Upfluence (among many others). Some of these also focus on specific platforms like TikTok or Instagram.

Influencer Marketplaces

Influencer marketplaces are newer and involve influencers opting into a marketplace platform to participate. Most offer a range of tools, but generally it is a two-sided platform between influencers and brands. Many influencers participate in multiple platforms. That said, these marketplaces also do some of the tough work around communication between brands and influencers and facilitate payment to influencers. Marketplaces attempt to make the process more seamless for both brands and influencers. Marketplaces also help with influencer discovery, campaign management, reporting, payment, contract negotiation and execution, connection with paid media, campaign tracking, and fake follower detection. The advantages of influencer marketplaces are that they are easy to use since everything is initiated in one place. This also lowers the barriers to entry for smaller brands and influencers since marketplaces assist with some of the more expensive tasks of campaign execution. Some disadvantages depend on the size of the marketplace. If it is too small, this limits the choice to brands. Because influencers opt in, there is little quality control. There can also be issues around time intensity for brands since some of the campaign implementation still falls to the brand’s team. There are advantages to influencers as well. “Because we are communicating with our influencers on such a regular basis, the reason that influencers sign up to be part of a network is that we have a lot of deal throughput,” said McCauley speaking about IZEA’s Unity Suite and Shake platforms. Unity Suite is the core platform that is the legacy marketplace of influencers. Shake is a newer marketplace that gives anyone direct access to hiring creators.

A few marketplaces include IZEA and ExpertVoice. IZEA has IZEAx-Discovery. It is a comprehensive influencer search platform that uses artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning to provide data for marketers about specific influencers. Some of the data include follower counts, the quantity of sponsored content, engagement rate over time and with specific assets, and content performance. IZEAxDiscovery is used with its influencer marketplace called Shake. Shake provides a seamless way for brands and creators and influencers to work.

DIY Influencer Campaign Tools

Some brands want to design and implement influencer marketing campaigns and just need some help making that happen. Some of the discovery platforms and marketplaces have additional tools that allow this to occur seamlessly. IZEA’s Unity Suite allows brands to search for influencers; communicate with them; create content; facilitate bidding, payment, and budgeting; distribute content; and monitor the results. This can be seen as an extension of a brand’s in-house capabilities.

There are agencies that specialize in matching not only brands and influencers but also content production and measurement. VaynerMedia, Obviously, Collectively, Captiv8, and 360i are all good examples of influencer agencies. Other influencer marketing agencies marry supply and demand by providing deep services to influencers and providing full service for brands. The primary reason to work with an agency is that it is full service meaning discovering and matching influencers, contracting, paying influencers, tracking results, and ensuring brand safety and Federal Trade Commission (FTC) disclosure results. The benefits include industry partnership that are well established with influencers, solid experience, access to data (which can be expensive), and campaign management. However, this comes with a price, and depending on the agency, it may be limited to digital marketing only as opposed to cross channel, integrated campaigns.

Estate Five is one such agency out of Dallas (with offices in Beverly Hills and New York) that focuses on mid- to macro-influencers. Estate Five provides a full suite of business services to influencers—from contact negotiation and payment to accounting and legal services. They also review content and ensure compliance with FTC disclosure. Five Estate essentially help them run their businesses. “We provide influencers with the services and experience in a space that is constantly evolving that they would not have on their own just sort of operating in a vacuum,” said cofounder and CEO of Estate Five Lynsey Eaton. Additionally, the company works with brands who want to work with their stable of talent and help with all aspects of planning and executing campaigns. Estate Five is also joined by a host of other companies that are essentially talent agencies for influencers. These include the likes of Viral Nation, NeoReach, Central Entertainment, and others.22

Other players in the ecosystems such as venture capital firms focus on the creator economy including ways to recognize and monetize the value of top creators as well as startups that help facilitate everything of community building to ecommerce, to customer relationships management and financing for creators. These are changing by the day as capital is poured into the ecosystem. Consider that an up-and-coming social media platform Clubhouse is an audio-only app that is already valued at more than $4 billion. It did not really exist a year ago. There are also niche players in the ecosystem dedicated to serving both brands and influencers. Talent agencies have also added influencers to their roster of clients. Last, there are numerous tools and technologies to assist influencers to create their work.23 More about this in Chapter 2. There is a lot to learn and a lot to keep up with as the industry grows and matures.

The Roadmap

Take a look online, and there is some fantastic content out there to learn how to be an influencer. Blogs, e-books, webinars, and courses—all great tools to learn about influencer marketing—are at the fingertips. There are also some really great books and podcasts too. I know … I have read them and listened to them. I particularly liked books by Amanda Russell and Neal Shaffer—both of whom examined influencer marketing—and in particular—social media influencers from a “boots on the ground” perspective. Both are influencers in their own right. Given the great practical content available, I decided to write a slightly different book. While this book is grounded in the practical implications for brands (including interviews with several people actively working in the business), it also incorporates academic research on celebrity endorsers as well as emerging research on social media influencers. There has been increased attention in social media influencers over the past 8 to 10 years, and much more to be learned. The goal for this book is to serve as the bridge between the rapidly increasing technological innovation that brands face when designing a campaign, the growing cultural capital that many social media influencers have, the growth in tools to facilitate the massive interest in the creator economy in general, and the theoretical foundations to help marketing managers to understand the “why” and “how” influencer marketing campaigns can work more effectively.

As part of this effort, I was able to talk with several very influential people working in influencer marketing as well as some people who have been instrumental in getting the work done. A huge thank you to Ryan Schram, COO and President of IZEA; Addi McCauley, Director, Client Development and Strategy at IZEA; Lynsey Eaton, cofounder and CEO Estate Five; Andrea Arias, Associate Brand Manager for Cetaphil (Galderma); Brittany Knight, lifestyle marketer for Nike, Speakers on Adweek’s Social Media Week LA conference held virtually June 29 to July 1, 2021; West Gissinger, Sessions Pilates fitness instructor, fitness influencer and brand ambassador for Outdoor Voices and Carbon38; and Preston Campbell, social media content creator for Kameron Westcott of the Real Housewives of Dallas and founder of Big Mood Marketing.

This introduction sets the roadmap for the rest of the book. The purpose of this introduction is to lay the foundation of social influence and the use of WOM marketing to disseminate brand messages. Theories related to social influence and WOM set up a good foundation to drive the efficacy of influencer marketing. Chapter 1 examines how marketing has shifted in the past with an emphasis on digital marketing, specifically content marketing, native advertising, and influencer marketing. It also introduces the Influencer Marketing Relationship Framework to examine how these concepts work together. Chapter 2 introduces the concept of the creator economy and examines what is driving people to become “creators” and build businesses around it. Chapter 3 defines influencer marketing and social media influencers—no easy task since there are no standard definitions of either concept. This chapter also examines the legacy of celebrity endorsers—traditional celebrities known for something outside of social media—and how they have been used for marketing. Chapter 4 examines the theories that have been used in the celebrity endorsement context. Social media influencers are a specialized case of endorsement, and new research on how social media influencers are similar and different to traditional celebrities is used to set forth a foundation for campaign creation. Chapter 5 examines how to design an effective campaign—everything from setting campaign goals and matching influencers and brands to designing the campaign format and gauging the results. Chapter 6 examines the results of influencer marketing campaigns as well as other issues to consider—from unintended consequences to FTC disclosure requirements. The last chapter examines the future of influencer marketing. The book balances practitioner content with academic research, with interviews sprinkled in so that the reader can get a full view of everything influencer marketing.