Making Trouble

WHO WANTS TO BE AN INVENTOR?

DON’T WORRY, NO ONE IS GOING TO STEAL YOUR SECRETS.

By Saul Griffith

FAR, FAR OUT THERE ON THE FRINGE OF society’s imagination is the backyard inventor who strikes it rich with some cunning little gizmo that improves life. You’ve seen this person portrayed by Wayne Szalinsky in Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, Doc Brown in Back to the Future, Bruce Wayne in Batman, and countless other fictional characters, including my favorite, Wallace, and the real brains of the operation, Gromit.

Every time Squid Labs is in the news somewhere, we receive a new batch of emails from home inventors: “Dear Sirs, I’ve invented an energy device. I need help in patenting it and prototyping it. It will revolutionize the world and save the children of Africa from starvation.”

Against my better judgment, I often send a reply: “Can you tell me a little more about your device so I can figure out if we can help?” Generally, I get the paranoid response: “If I tell you any more, you will know what the invention is!” To which I have to say, “Without more information I can’t help you. Good luck.” And in the back of my mind I imagine another perpetual motion machine.

This phenomenon reminds me of Tim O’Reilly’s writing regarding authors: “Lesson 1: Obscurity is a far greater threat to authors and creative artists than piracy.” Which might just as easily be translated as: Obscurity by secrecy is a far greater threat to inventors than having your ideas stolen by corporations.

I know a lot of people who invent things, even for a living, but I can’t say I know anyone who represents the mythical backyard inventor who retires to live a life of luxury on the royalties of their patent. It is a concept fueled by the American dream and in the media offerings that support that dream, but it is not a reality.

I suspect that what would be most helpful is to step back and understand what it is that “inventors” really want, and figure out what would be their best strategy to get it. Like musicians, artists, and the other obsessively creative types, most innovators really just want to earn a good living doing what they love. Inventors, deep down, would like to be paid for full-time tinkering. If they could retire with the proceeds and buy yachts, that would be ideal, but I suggest that having the resources to do what they love and a workshop to do it in is way more important than the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

I’ll return to O’Reilly’s words to string my own thoughts together: “For all of these creative artists, most laboring in obscurity, being well-enough known to be pirated would be a crowning achievement.” Again, these words apply directly to inventors and the process of invention. You’ll be better off in the long run being known for inventing something — even if you give it away — than hoarding the idea in a padlocked file cabinet in your basement.

I know a lot more people who publicized ideas that turned into careers or job offers than I do people who made it big with that mousetrap. I don’t actually know anyone who has been “screwed” by “bastard corporations” or other “thieving inventors.”

Of course I always console my friends when they don’t think their licensing deal was good enough, but it’s really the same counseling they get from me over thinking about exes: “Of course they were [insert epithet] but now you are out of it, and better off for it.”

Let’s briefly look at the other option, the “patent and sell” dream. A single patent through to prosecution will cost you anywhere from $20,000 to $100,000, depending on how much of the world it covers. This is before you’ve gone through the expense of trying to license your patent to someone (before you make any money, you’ll have to spend a lot letting interested parties know about the idea). Alternatively, you can wait until someone infringes your patent and then try to recover monies from their error. This is even more expensive. I rarely recommend this process to any individual inventor. The likelihood of a yacht retirement outcome is similar to the likelihood that you look like Bruce Wayne.

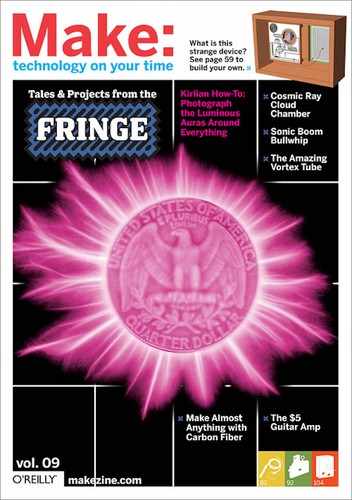

Famous inventors of fiction and reality. Top: Bruce Wayne and Wayne Szalinsky. Bottom: Thomas Edison and who knows? It could be you. Just don’t expect to retire to a life of luxury after filing a single patent.

Illustration by Dustin Hostetler

Patents and secrecy don’t really serve the individual anymore. Unfortunately, they have become trading cards in a grand corporate shell game. I’d stand by the statement that the most likely road to the tinkering nirvana is to become known for what you do. That means doing it well and telling people about it, even telling them how to do it.

The reality is that the invention or the idea is a tiny fraction of the work to be done, and in all probability other people have already had the idea or patented the same thing. The real tradeable value is your capacity to implement the idea. I’ve hired people because they’ve built cool projects on instructables.com that demonstrated their skill, and I’ve seen people turn their kit-building websites into profitable small businesses. It all started with pretty much giving a few of their inventions away — loss leaders to support a lifetime of tinkering.

To read Tim O’Reilly’s essay “Piracy is Progressive Taxation, and Other Thoughts on the Evolution of Online Distribution,” go to makezine.com/go/piracy.

Saul Griffith thinks about open source hardware while working with the power nerds at Squid Labs (squid-labs.com).

Photograph by Howard Cao