Chapter 7

Understanding GST

In This Chapter

Getting your head around how GST works

Deciding whether to register for GST, and what boxes to tick if you do

Forging neural pathways with amazing feats of multiplication and division

Applying this strange and wonderful tax to real-life situations

Setting up tax codes in your accounting software

Keeping your nose squeaky clean

Making sure your paperwork is up to scratch

Holey moley. As part of researching this chapter, I decided to download ‘The Simple Guide to GST’ from the Australian Taxation Office website, along with its twin sister equivalent from Inland Revenue in New Zealand. Many hours and 168 pages later, I was left with a strange sensation which I couldn’t quite put into words.

Then in the night it came to me. Obfuscation was the word I was looking for. According to Wikipedia wisdom, obfuscation is the ‘concealment of intended meaning in communication, making communication confusing, intentionally ambiguous and more difficult to interpret’. A more succinct definition of government-generated documents I could not imagine.

Never mind. Hopefully, the price of my suffering can be an exchange for your peace of mind. In this chapter, I take a stab at distilling how GST works, some of the do’s and don’ts of accounting for GST, what mistakes to watch out for, and how to peel a grape with your tongue — no fingers or teeth allowed. (Ah, the useful skills one learns late at night in Sydney’s bars.)

Coughing Up the Difference

As you probably already know, GST stands for Goods and Services Tax and is a tax that applies to most goods and services in Australia and New Zealand. Every time you buy a glass of wine or a new item of furniture, or you get your lawn mowed, you pay GST of either 10 per cent (Australia) or 12.5 per cent (New Zealand). Note: The New Zealand rate may have changed by the time you read this — please double-check.

As a business that’s registered for GST, you pay GST on your supplies and collect GST on your sales. You have to keep a set of books that tracks how much GST you pay and how much GST you collect. If GST collected is more than GST paid, you pay this difference to the government. If GST collected is less than GST paid, you claim a refund.

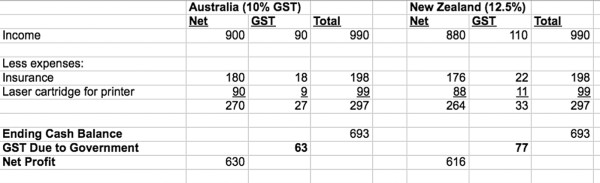

For example, imagine a bookkeeper who charges a client $990 for a week’s work. In that same week, the bookkeeper pays an insurance premium of $198, as well as $99 for a new laser cartridge. Figure 7-1 shows how the sums work. In both Australia and New Zealand, this bookkeeper is left with $693 in the hand after a week’s work. However, the bookkeeper is now in debt to the government (aren’t we all) for the difference between GST collected and GST paid. In Australia, this GST equals $90 less $27, making a difference of $63 due to the government. In New Zealand, this difference is $77.

Figure 7-1: Calculate the difference between GST collected on sales and GST paid on purchases.

Signing Up (Is There a Choice?)

Don’t plunge into the whole GST shenanigans without thinking through your options. Does every business have to register? And, if not, are there situations when a business is better off not to register? What accounting basis is best? How often should you lodge reports? I answer all these questions, and a bit more besides, in the next few pages.

Submitting to the inevitable

In Australia, registering for GST is optional if your turnover is less than $75,000 a year and, in New Zealand, registering is optional if your turnover is less than $60,000. (Note: In Australia, you get two exceptions to this rule: The turnover threshold increases to $150,000 for not-for-profit organisations, and taxi drivers have to register, regardless of income.)

I haven’t got enough space here to go into the definitions of how to calculate turnover and as a bookkeeper you’re not responsible for this detailed kind of tax advice. However, as soon as your client (or you, if you’re a business owner reading this book) starts to make sales of $1,000 or more a week, flick the alert button and contact the accountant for advice.

If you’re starting a new business, you can register for GST at the same time as you apply for an ABN (in Australia), or when you register as a business (in New Zealand). (For more about ABNs or registering your business, refer to Chapter 1.) On the other hand, if you’re already up and running in business and now want to alter your details to register for GST, contact the Tax Office in Australia on 13 28 66 or phone New Zealand’s Inland Revenue on 0800 377 774.

In Australia, you can register for an ABN but choose not to register for GST. However, you can’t register for GST unless you have an ABN. Similarly, in New Zealand, you can register for an IRD number but choose not to register for GST. However, you can’t register for GST unless you have an IRD number. (For a sole trader or partnership in NZ, the IRD and Gst numbers are generally the same.)

Choosing not to register

If a business chooses not to register for GST, it doesn’t have to charge GST on customer sales. However, don’t be hoodwinked into imagining that this business escapes paying GST on purchases: Other businesses have to charge GST on everything they sell, regardless of who they sell to. A non-registered business has to pay GST but can’t claim it back, although the full amount of the purchase can be claimed as a tax deduction.

Registering for GST when you don’t have to doesn’t make sense for many small businesses. My neighbour chose not to. He runs a small lawn-mowing business that turns over about $600 a week, an income that falls short of the threshold over which he’d have to register. He chose not to register because that way he doesn’t have to charge customers GST, and his prices are more competitive.

Ignore that urban myth that suggests if a business doesn’t register for GST, customers don’t want to trade with it. As long as a business has an ABN (Australia) or IRD number (New Zealand) and the prices are competitive, most customers don’t mind either way.

Picking a reporting method to suit

When a business registers for GST, it has to choose whether to account for GST on a cash, accrual or hybrid basis (the hybrid option only applies to New Zealand businesses).

Cash or payments basis: Cash basis reporting (also known as payments basis in New Zealand) means you only pay GST when you receive payments from customers and you only claim back GST when you make payments to suppliers. Note that a business can only report for GST on a cash basis if it has a turnover of less than $2 million per year (this threshold is the same in both countries).

If a business tends to owe less to suppliers than what customers owe to it, cash basis reporting works best. This is the most popular method for small businesses in both Australia and New Zealand.

Accrual or invoice basis: Accrual basis reporting (also known as invoice basis in New Zealand) means you pay GST in the period that you bill the customer or receive a bill from the supplier, regardless of whether any money has exchanged hands. This approach means that if you bill a customer in March and they don’t pay until July, you have to pay the GST in April regardless. Similarly, if you receive a bill from a supplier in March and you don’t pay them until much later, you still claim back the GST in April.

If a business tends to owe more to suppliers than what customers owe to it, accrual basis reporting works best.

Hybrid basis (available in New Zealand only): The hybrid basis is a combination of cash and accrual accounting. You pay GST on sales in the period that you invoice the customer, regardless of whether they’ve paid you or not. However, you can only claim GST on supplier bills after you’ve paid them. A few larger businesses choose hybrid reporting if they just use a manual cashbook and don’t run a creditors ledger, because this method saves making end-of-period adjustments for creditors. However, I don’t recommend this method — Inland Revenue is the only mob that wins.

You can choose to report for GST on a different basis to income tax. For example, you can choose to report for GST on a cash (payments) basis and report for tax on an accrual (invoice) basis, or vice versa. Most small businesses opt to report on a cash (payments) basis for both GST and income tax purposes.

You may be feeling bamboozled by all this tax chat. No sweat — the important thing for you to realise is that any selection you (as a business owner) or your client (if you’re a bookkeeper) makes regarding the GST reporting basis or accounting basis may have a big impact on business cashflow. If in doubt, speak to an accountant first.

Reporting for duty

In Australia, if a business turns over $20 million per year or less, it can choose to report for GST on a monthly, quarterly or annual basis. In New Zealand, businesses can choose to file monthly, bi-monthly or six-monthly (the six-monthly option is only available for smaller businesses with a turnover of less than half a million dollars per year).

Most businesses choose to report every two months (in New Zealand) or every three months (in Australia), striking a happy balance between the hassle of monthly reporting, and the psychological hurdle of only doing books every six months or every year. The only instance that monthly reporting makes sense is for businesses that regularly receive GST refunds, such as exporters.

In New Zealand, when you register for GST you have the option to align your GST reporting period-end with the financial year-end (otherwise known as your balance date). Be smart and agree to this option, because aligning reporting periods makes life heaps easier for both you as a bookkeeper, and also your accountant.

Calculating GST

I hope you realise that the introduction of GST heralded a major shift in the education system. Forget multiplying by two, dividing by five or understanding fractions. Cast algebra to the wind, and speak not of spelling or grammar. To get by in the world of GST, Aussie children need to be wizards at multiplying by ten and dividing by eleven. Life is worse for Kiwis, who have to multiply everything by 12.5 and divide by 9. Oh horrors of horrors.

Stay cool. In the next couple of pages, I walk you through a few worked examples of how to add GST, then take it off again.

Going decimal the Aussie way

To calculate how much GST to add to something, simply multiply the figure by 10 per cent or 0.1. For example, if an item costs $10 and you want to find out how much GST to add, you do the following:

$10 × 0.1 = $1

To add GST onto something you either add 10 per cent (using the per cent button on your calculator) or you multiply the amount by 1.1. For example, if something is $10 and you want to add 10 per cent, you do the following:

$10 × 1.1 = $11

If an amount already includes GST, and you want to calculate the GST component, you simply divide the amount by 11. For example, if you buy something for $110 and you want to figure how much GST is in the total, you do the following:

$110 ÷ 11 = $10

To figure out what the cost of this item was before GST was added, you divide the total cost by 1.1. For example, if you buy something for $110 and you want to figure out how much this item cost before GST, you do the following:

$110 ÷ 1.1 = $100

Keeping quirky east of the Tasman

To calculate how much GST to add to something, simply multiply the figure by 12.5 per cent or 0.125. I say ‘simply’, but Lynley (who contributes the New Zealand content in this book) remembers that the introduction of a 12.5 per cent GST in 1986 meant that some older business owners, including Lynley’s dad Walter, had to learn how to use a calculator for the very first time. Note: At the time of writing, rumours that this rate was set to increase were rife, but not confirmed. Please double-check the current rate before you continue reading.

So, if an item costs $10 and you want to find out how much GST to add, you do the following:

$10 × 0.125 = $1.25

To add GST onto something, you either add 12.5 per cent (using the per cent button on your calculator) or you multiply the amount by 1.125. For example, if something is $10 and you want to add 12.5 per cent, you do the following:

$10 × 1.125 = $11.25

If an amount already includes GST, and you want to calculate the GST component, you simply divide the amount by 9. For example, if you buy something for $112.50 and you want to figure how much GST is in the total, you do the following:

$112.50 ÷ 9 = $12.50

To figure out what the cost of this item was before GST was added, you divide the total cost by 1.125. For example, if you buy something for $112.50 and you want to figure out how much this item cost before GST, you do the following:

$112.50 ÷ 1.125 = $100

Fortunately, most accounting software calculates GST automatically. With both MYOB and QuickBooks you can choose to enter prices either excluding or including tax (for example in MYOB, you make this selection by toggling the Tax Inclusive button; in QuickBooks you toggle the Amounts Include Tax button). Then, as soon you enter a tax code, the software automatically calculates the tax. Sweet as a nut.

Figuring What’s Taxed and What’s Not

When you talk about whether GST applies to stuff, or not, you get four different scenarios.

Scenario number one: Regular GST, which you either pay or you get charged, and which you report on your Business activity statement (Australia) or GST return (NZ). Most transactions fall into this category. For more details, skip ahead to ‘Move it, groove it, tax it’.

Scenario number two: GST isn’t charged or claimed but you have to report it on your Business activity statement (Australia) or GST return (NZ). For example, you don’t charge GST on exports, but you do have to report all export income. For more details, skip ahead to ‘Transactions with no GST (Australia only)’ or ‘Transactions with no GST (NZ only)’.

Scenario number three: In this scenario, you don’t charge GST or pay GST and you don’t report it either. For more details, skip ahead to ‘Transactions with no GST (Australia only)’ or ‘Transactions with no GST (NZ only)’.

Scenario number four: In this scenario, the supplier charges GST but you can’t claim it. This applies if you aren’t registered for GST, but the supplier is, or if you’re a landlord of residential real estate and you can’t claim back the GST on related purchases. For more details, skip ahead to ‘Transactions with no GST (Australia only)’ or ‘Transactions with no GST (NZ only)’.

Move it, groove it, tax it

Almost as certain as death and as painful as unrequited love, most things get taxed. In Australia, where the love of inefficient bureaucracy and red tape betrays a colonial legacy, a flat GST of 10 per cent applies to most goods and services, but with a long list of exceptions. You know, a bottle of orange juice from a supermarket doesn’t have GST, but a bottle of orange juice from a takeaway café does; bandages and band-aids don’t have GST, but tampons most certainly do (at this point, does one detect patriarchal as well as colonial influences at work?).

In New Zealand, the system is eminently more sensible, where a flat GST of 12.5 per cent applies to pretty much all goods and services, with a short list of very obvious and sensible exceptions.

I’ll cut to the chase. As a bookkeeper, if you’re doing the books for a business that’s registered for GST, then you need to keep track of two things: How much GST you collect on sales, and how much GST you pay out on purchases. If you do handwritten books or use a spreadsheet, you track GST by creating a separate column for tax. If you use accounting software, you have a special code for each transaction that indicates the tax status.

In Australia, you get an added complication (but of course!). If a business buys capital items over $100 (or $1,000 if a business is eligible for Small Business Tax Concessions), you have to report these purchases separately on your Business activity statement.

Transactions with no GST (Australia only)

In Australia, transactions that don’t attract GST fall into three categories:

Transactions that are GST-free that you report on your Business activity statement

Transactions that are input-taxed that you report on your Business activity statement

Transactions that don’t attract GST and that you don’t report on your Business activity statement

I expand a little on each of these categories in the headings below.

Transactions that are GST-free that you report on your Business activity statement

GST-free transactions are transactions where you don’t charge for GST on sales or pay GST on purchases, but you report separately for these sales or purchases in your Business activity statement.

GST-free transactions include childcare, educational courses, essential non-processed foods, export sales and medical supplies.

Transactions that are input-taxed that you report on your Business activity statement

Another type of income and expense that has no GST, but you still need to report, is income and expenses relating to residential properties. As a landlord, you can’t charge GST on rent, nor can you claim GST on rent-related expenses. This kind of income is called input-taxed income, and the related expenses are called input-taxed purchases.

Income from interest and dividends is also input-taxed.

Transactions that don’t attract GST and that you don’t report on your Business activity statement

This third category covers all transactions that don’t attract GST, but that you also don’t report on your Business activity statement. These transactions include

Internal transactions within a business, such as cash transfers, depreciation, transfers between accounts, movements in stock and loan repayments

Payments of tax itself (there is no GST on GST . . . yet!)

Personal spending or drawings or owner’s contributions

Wages and superannuation

Transactions with no GST (NZ only)

In New Zealand, transactions that don’t attract GST fall into three categories:

Transactions that are zero-rated that you report on your GST return

Transactions that are exempt that you don’t report on your GST return

Transactions that are non-taxable that you also don’t report on your GST return

I expand a little on each of these categories in the headings below.

Transactions that are zero-rated that you report on your GST return

The only transactions that are zero rated in New Zealand are exports, the sale of a going concern (a business) and imported services. In other words, if you export goods or services overseas, you don’t charge GST on these goods and services, but you do report the total income on your GST return in the zero-rated field on the form.

Transactions that are exempt that you don’t report on your GST return

Exempt transactions are transactions where you don’t charge for GST on sales or pay GST on purchases, and you also don’t report separately for these sales or purchases in your GST return.

The list of exempt transactions includes donated goods, financial services (such as bank fees, merchant fees and bank interest) and income or expenses related to residential investment properties.

Transactions that are non-taxable that you also don’t report on your GST return

Similar to exempt transactions, non-taxable transactions occur where you don’t charge for GST on sales or pay GST on purchases, and you also don’t report separately for these sales or purchases in your GST return. The difference between exempt and non-taxable transactions is pretty academic, as you don’t report either kind of transaction on your GST return. In fact, many accountants don’t bother distinguishing between exempt and non-taxable, and use the same column (in handwritten books or spreadsheets) or the same code (in accounting software) for both kinds of transactions.

Transactions that are non-taxable include

Internal transactions within a business, such as cash transfers, depreciation, transfers between accounts, movements in stock and loan repayments

Payments of tax itself (there is no GST on GST . . . yet!)

Personal spending or drawings or owner’s contributions

Wages and superannuation

Setting Up Tax Codes in Accounting Software

Earlier in this chapter, I explain that you get three different scenarios with GST: Sales or purchases with GST that you report on your Business activity statement or GST return; sales or purchases without GST that you report on your Business activity statement or GST return; and last, sales or purchases without GST that you don’t report on your Business activity statement or GST return. When you work with accounting software, you need a tax code for each of these scenarios, plus a couple more besides.

In the next few pages, I explain how to set up tax codes for both Australia and New Zealand, and then how to link the accounts in your chart of accounts to these tax codes.

Creating a list of tax codes (Australia)

Here’s a quick-and-dirty summary of how to set up tax codes for both MYOB and QuickBooks. Other accounting software may have slightly different approaches, but the principles are the same regardless of what software you use.

1. Make sure you have a tax code for GST sales and purchases.

In MYOB, this code is simply GST. In QuickBooks, this code is GST, or alternatively NCG (for GST on Purchases) and GST (for GST on Sales). By the way, in QuickBooks, you also need to customise a tax items list so that QuickBooks knows how to report tax codes on your Business activity statement. For more details, refer to my tome QuickBooks QBi For Dummies or refer to QuickBooks help.

2. Create a code for GST purchases that are also capital acquisitions.

I talk more about capital acquisitions earlier in this chapter in the section ‘Move it, groove it, tax it’. In MYOB, this code is usually either CAP or GCA. In QuickBooks, this code can be either CAP or CAG.

3. Create another code for items that are GST-free.

In MYOB, this code is simply FRE. In QuickBooks, this code can be either FRE, or NCF (for GST-free purchases) and FRE (for GST-free sales).

4. Now create a tax code for input-taxed sales and, if necessary, another for input-taxed purchases.

Input-taxed sales is a fancy name for interest income, dividend income or residential income. In both MYOB and QuickBooks, I use the code ITS for input-taxed sales. For expenses that relate directly to input-taxed sales (property expenses, for example), I use a code called INP.

5. Last, create a code for non-reportable transactions.

In MYOB, the N-T code is the one to use for non-reportable transactions. Because MYOB uses N-T as the default, this tax code automatically comes up on transactions unless you select something else.

In QuickBooks, I suggest you create a new tax code called NR for non-reportable transactions. Some people don’t bother using any code for non-reportable transactions in QuickBooks, but I don’t recommend this method. Unless you enter a tax code for every transaction, it gets tricky to distinguish between transactions where you have forgotten to enter a tax code and transactions that you know are non-reportable or exempt.

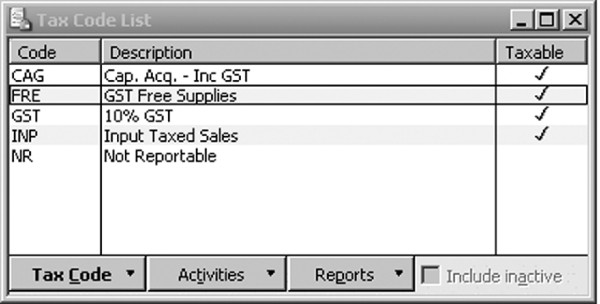

6. Do a pirouette or two, then see if your list of tax codes looks anything like Figure 7-2.

I show the QuickBooks tax code list in Figure 7-2, but the tax codes list in MYOB looks much the same.

Figure 7-2: Setting up tax codes (Australia only).

Copyright © 2010 Intuit Inc. All rights reserved

The list I show in Figure 7-2 is perfect for 99 per cent of businesses. However, some businesses may need additional tax codes, specifically if you (or the business you’re working for) are required to report for ABN withholding tax, export sales, luxury car tax, voluntary wine equalisation tax or withholding tax. If any of these taxes apply, get advice from your accountant.

Creating a list of tax codes (NZ)

In the following steps I give a summary of how to set up tax codes for both MYOB and QuickBooks — the instructions are the same for both. (In QuickBooks, you also need to customise a tax items list which defines how to report tax codes on your GST return. Refer to your QuickBooks user guide for the finer details.) Other accounting software may have slightly different approaches, but the principles are the same regardless of what software you use.

1. Make sure you have a tax code for GST sales and purchases.

This code is simply S (which stands for a standard rate of 12.5 per cent).

2. Create another code for items that are zero-rated.

You guessed it: The usual code is Z. Deceptively simple.

3. Create a code for exempt transactions.

In MYOB, you can use either E (standing for exempt) or N-T (which is the default tax code if you don’t enter anything else). In QuickBooks, either the code E or N does just fine.

4. If you import goods from overseas, create a code for Customs GST.

You report GST paid in imported goods separately. Different consultants have different methods of reporting for GST paid to customs, and MYOB and QuickBooks also differ in their approaches, so get advice regarding the setup and rate for this code.

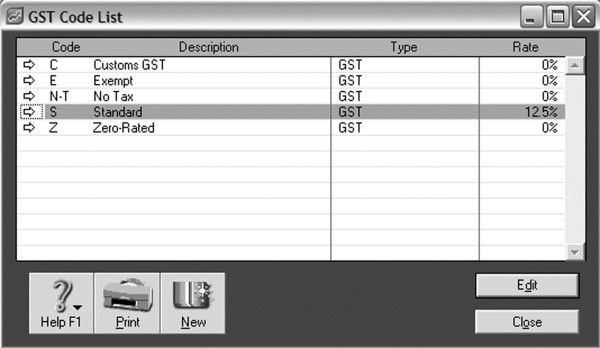

5. Check that your list of tax codes looks similar to Figure 7-3.

I show a tax codes list from MYOB in Figure 7-3, but the tax codes list in QuickBooks looks pretty similar.

Figure 7-3: A typical tax codes list (New Zealand only).

Linking accounts to tax codes

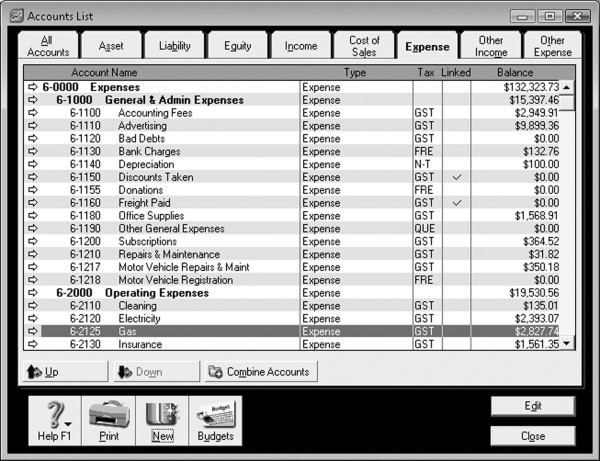

The secret to producing an accurate Business activity statement or GST return is to get the tax code right on every transaction. In both MYOB and QuickBooks, you can make this process pretty easy by linking each account in your chart of accounts with a specific tax code. (For more about building your chart of accounts, refer to Chapter 2.)

You can see how this works in Figure 7-4, where I show a typical chart of accounts from MYOB. Obviously, the format of this chart varies depending on whether you use MYOB or QuickBooks, and whether you’re working in Australia or New Zealand, but the concept is the same: Because each account is linked to a specific tax code, the correct code comes up every time you select an account. For example, if the tax code for Advertising Expense is GST, then every time you allocate a payment transaction to Advertising Expense, GST pops up automatically as the tax code. (In MYOB, you can link tax codes to every account; in QuickBooks, you can link tax codes to income, cost of sales and expense accounts only.)

Figure 7-4: Configure your chart of accounts so that each account corresponds to the correct tax code.

The implications are huge: If you set up the correct tax code for every account in your chart of accounts correctly, right from the start, you’re almost guaranteed of coding all your transactions right, every time. Perfection and nirvana are but moments away.

Staying Out of Trouble

I have a sister who is a tax auditor specialising in big-time customs fraud. She’s relatively high up these days, and she spends most of her time interviewing the underworld individuals who make the baddies in a James Bond movie look like kittens. ‘Interrogations’, she likes to call these interviews, with a steely glint in her eye and a tightening of the upper lip.

I imagine that 99.99 per cent of the bookkeepers reading this book have nothing to fear from a fraud investigation, even if conducted by my fearsome sister. However, the dread of a tax audit looms high for even the most conscientious of bookkeepers. Usually, the fear isn’t so much that an auditor finds that you’ve consciously covered up income or over-claimed something like GST refunds, rather the fear is that you’ve made a mistake by accident and now you’ll get into trouble.

So in the interests of making sure you get a good night’s sleep, year in year out, I provide a few handy hints for getting everything just right.

Avoiding traps for the unwary

So you know the theory, and now you’re responsible for deciphering the tax status of hundreds of transactions. What are the most common mistakes to look out for?

Australia

Bank fees and merchant fees: Bank fees are GST-free, but merchant fees and the hire of EFTPOS machines attracts GST.

Government charges: Council rates, filing fees, land tax, licence renewals, motor vehicle rego and stamp duty are all GST-free.

Insurance: Almost every insurance policy is a mixture of being taxable and GST-free (stamp duty doesn’t have GST on it). Don’t get caught out. Instead, double-check the exact amount of GST on every single insurance payment.

Loan payments and hire purchase: You can’t claim GST on loan payments, nor can you claim GST on the total amount of hire purchase payments. With hire purchase, the correct treatment is either to claim the whole amount of GST when you originally purchase the asset, or to claim the GST progressively on each payment, splitting up the interest and the principal. (Clear as mud? Ask your accountant for advice.)

Overseas travel: Overseas travel is GST-free, meaning that you must report the expense, but no GST applies.

Personal stuff: You can’t claim the full amount of GST on expenses that are partly personal — motor vehicle and home office expenses are the obvious culprits. (See the later section ‘Keeping personal matters separate’ for more details.)

Petty cash: Petty cash is usually a mixed bag. Coffee and tea are GST-free, biscuits and sticky-tape aren’t.

Small suppliers: Watch out for small suppliers who have an ABN but aren’t registered for GST. Record these purchases as GST-free.

Tax Invoices: You can’t claim GST on any amount over $82.50 (GST-inclusive) unless you have a Tax Invoice. (But remember that in any case, you need a copy of every single receipt and invoice for income tax purposes.)

New Zealand

Bank fees and merchant fees: Both bank fees and merchant fees are exempt from GST, but the hire of EFTPOS machines attracts GST.

Loan payments and hire purchase: You can’t claim GST on loan payments, nor can you claim GST on the total amount of hire purchase payments. With hire purchase, the correct treatment is either to claim the whole amount of GST when you originally purchase the asset, or to claim the GST progressively on each payment, splitting up the interest and the principal. (Clear as mud? Ask your accountant for advice.)

Overseas travel: Overseas travel is zero-rated, meaning that you must report the expense, but no GST applies.

Personal stuff: You can’t claim the full amount of GST on expenses that are partly personal — motor vehicle and home office expenses are the obvious culprits. (See the later section ‘Keeping personal matters separate’ for more details.)

Small suppliers: Watch out for small suppliers who have an IRD number, but aren’t registered for GST. Record these purchases as non-taxable.

Tax Invoices: You can’t claim GST on any amount over $50.00 (GST-inclusive) unless you have a Tax Invoice. (But remember that in any case, you need a copy of every single receipt and invoice for income tax purposes.)

Keeping personal matters separate

If a business owner purchases goods or services that they use partly for private purposes, then be careful not to claim the GST on the private component.

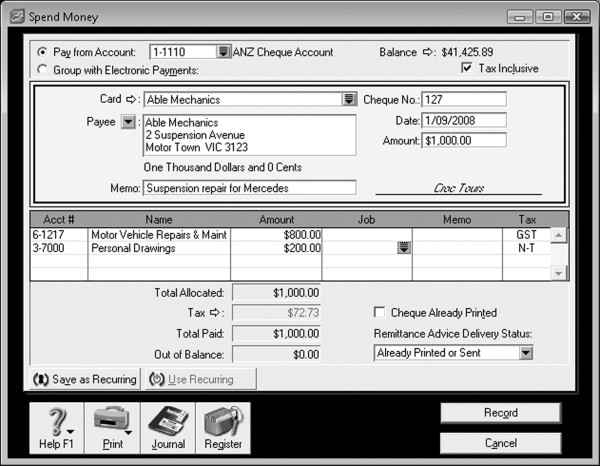

For example, if you (or the business owner) claim your motor vehicle as a business expense, but your log book shows that 20 per cent of use is actually personal, then you can only claim 80 per cent of the GST when you record the transaction. For example, Figure 7-5 shows how Maryanne pays for motor vehicle repairs on her Mercedes sports car. The total bill is for $1,000 but when she records the payment, she only allocates $800 to Motor Vehicle Repairs, allocating the remaining $200 to Personal Drawings.

The other approach is to claim the whole amount of GST with every transaction and request the accountant make an adjustment at the end of the financial year. This method works okay, but isn’t quite as accurate as recording transactions correctly throughout the year, and may of course cost the business a tad extra in accounting fees.

Figure 7-5: Apportioning personal expenses.

Dancing the Paperwork Polka

As soon as you register for GST, you need to make sure that every invoice you supply to customers includes certain key information, such as your business name, your ABN (if in Australia) or your GST number (if in New Zealand), the date and so on. In turn, you need to keep a beady eye on your suppliers’ bills so that they do the same, providing you with all the info you need in order to be able to claim GST back from your payments to them.

Riveting stuff? I’m on the edge of my seat as well. Read on for a detailed checklist of what’s required.

Brewing up a Tax Invoice

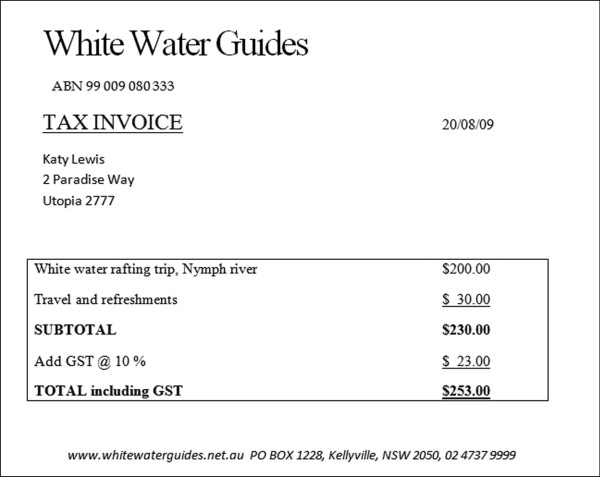

If you’re registered for GST and you send a client an invoice that’s for more than $50 (in New Zealand) or $75 (in Australia), before GST, then you must issue a Tax Invoice. The invoice needs to include the following:

Your ABN (if in Australia) or your GST number (if in New Zealand) and your business or trading name. Because an invoice is essentially a contract, the legal beagles recommend you stick this info at the very top of each invoice, above the details of what it is that you’re selling.

The words ‘Tax Invoice’ written clearly in nice big letters on the first page of the invoice.

The date.

A brief description of whatever it is that you’re supplying.

If the invoice is for taxable goods or services only, you need to either show the total amount of GST payable or add a comment saying that the total price includes GST.

If the invoice is for a mix of taxable and non-taxable goods (this situation only occurs in Australia), clearly identify each item that’s taxable and show exactly how much GST is payable.

If an invoice comes to more than $1,000 (including GST), you need to include some additional info:

In Australia, you also need to include either your customer’s name and address or your customer’s name and ABN.

In both Australia and New Zealand, invoices over $1,000 must include the quantity or volume of whatever it is that you’re supplying. For example, the number of hours charged, or the number of units supplied.

You can see a typical Tax Invoice in Figure 7-6.

Figure 7-6: A typical Tax Invoice.

Tax Invoices don’t need to be complicated documents. So long as you include the bare legal information I outline, a Tax Invoice can be as simple as a cash register docket, a hand-written scrap of paper or a short and tender email.

Checking supplier bills

In the same way as you’re responsible for making sure that you issue legit Tax Invoices to customers, you also need to make sure that your supplier bills toe the line.

Make sure that supplier bills include the supplier’s ABN (or GST number if you’re in New Zealand), an accurate description, the date and the total amount payable. If the supplier is registered for GST, the invoice should also say ‘Tax Invoice’ at the top, and either a statement that GST is included or a subtotal showing the amount of GST charged. Last, any invoice over $1,000 needs to show the quantity or volume of the goods or services supplied, such as litres of petrol or hours of labour.

If you operate under a company structure, make sure that whenever you (or the business owner) purchase new business equipment, the bill is made out to the company name and not to an individual name. Tax auditors (particularly in New Zealand) are always on the lookout for ‘other’ bills, and bills made out to individuals aren’t deductible.

Most suppliers include these details on bills as a matter of course. However, watch out for incidental receipts, and stay tuned to the fact that the slip of paper you get when you pay for something by credit card or EFTPOS is often separate to the receipt itself. This kind of docket, which usually just shows the date and the total amount paid, isn’t a legitimate receipt as far as your tax is concerned. (I guess the tax auditors are trying to cover for all those situations where someone buys $40 of petrol on their credit card and then chucks in a couple of Paddle Pops for the kids on top.)