Chapter 12

Reporting for Payroll

In This Chapter

Reporting for how much wages tax and superannuation a business owes

Keeping on top of other kinds of payroll expenses

Tidying up payroll accounts at the year’s end

Providing employees with wages summaries, and more

Making sure you toe the line with minimum pay and conditions

Bookkeeping is the only word in the English language I can think of that has three double letters in a row (double ‘o’, double ‘k’, double ‘e’). All this doubling up is entirely appropriate when you think of the winning strategy of all good bookkeepers: Double-checking, double-checking and then double-checking again.

I guess the heavy thing about being responsible for payroll is that you’re dealing with other people’s lives. If you make a mistake, maybe reporting the wrong amount of tax or wages on an employee’s annual summary, that person can end up with a scary tax bill. If you forget someone’s superannuation payment, that employee simply misses out. And yes, when that person retires and ends up eating porridge rather than scotch fillet, it’s you that’s to blame.

To be honest, I actually prefer porridge to scotch fillet. And in this chapter, I explain step by step everything that’s involved in making sure your payroll reports are correct, including how to balance payroll accounts, check payroll liability reports, and deal with tricky stuff such as payroll tax and fringe benefits.

I also explain how to find out about minimum pay and conditions, so that when an employee does eat porridge every morning, you know it’s a matter of bizarre personal preference, rather than a consequence of a Dickensian workplace.

Accounting for Payroll Liabilities

The main payroll liabilities that all employers have to report for include

PAYG withholding tax (Australia)/PAYE tax (New Zealand): This is the tax you deduct from employees’ wages. Note: In Australia, don’t confuse PAYG withholding tax with PAYG instalment tax. PAYG instalment tax is tax paid on company earnings.

Superannuation: In Australia, employers pay a flat 9 per cent of wages in superannuation (this payment is called the Superannuation Guarantee Contribution), although employees sometimes choose to pay additional superannuation also. In New Zealand, superannuation goes by the rather cute name of KiwiSaver and both the employer and the employee contribute a minimum of 2 per cent each.

Other payroll liabilities you may have to report for include

Child support deductions: If you have an employee who pays child support, you may have to deduct child support from this employee’s wages. You then send this amount monthly to the Child Support Agency (Australia) or to Inland Revenue (New Zealand).

Payroll tax (Australia only): Payroll tax is a state-based tax imposed on businesses with larger payrolls (upwards of $600,000) of between 4 and 6 per cent of the total wages bill. See ‘Hitting the payroll tax threshold’ later in this chapter for details.

Staff loans or garnishee orders: Garnishee orders are when a third party (such as the Tax Office or IRD) serves an order on an employer to deduct money from employee wages to pay off outstanding debts.

Salary packaging deductions (Australia only): Many not-for-profit organisations pay personal expenses such as rent or mortgage payments on behalf of their employees, and only tax employees on wages after deducting these payments. Many other businesses include benefits such as laptops as part of employee salary packages.

Student loan repayments: In Australia, employees with outstanding student debts simply go onto a higher tax scale, but in New Zealand, you calculate student loan repayments separately.

Union fees payable: Some employees ask to have union fees deducted from their wages. You need to send these fees to the union each month.

Checking payroll liability reports

When you record employee pay, you don’t just record journals that debit wages and credit cash. Most payroll transactions involve journal entries that affect several accounts, and credit at least one payroll liability account. For example, Figure 12-1 shows the debits and credits behind a regular paycheque where I pay an employee $800 in gross wages, but take out tax of $128. (Note: In New Zealand, the accounts are PAYE Tax, not PAYG Withholding Tax, and KiwiSaver Payable not Superannuation Payable, but otherwise the principles are the same.)

Figure 12-1: Every paycheque usually involves several debits and credits.

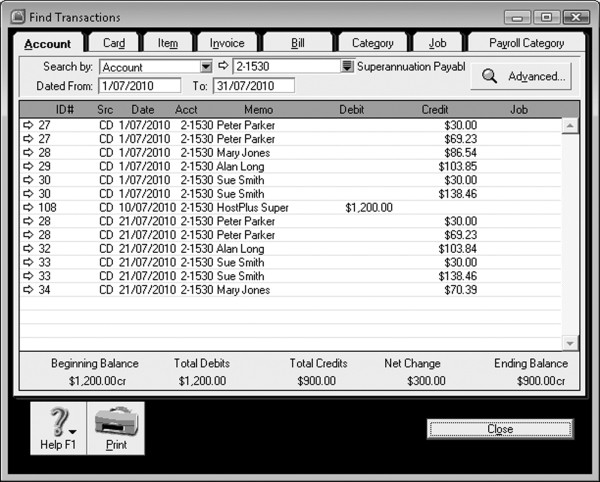

The idea with payroll liability accounts is that as the month or quarter progresses, the balance in the liability account increases with every paycheque you record. Then, when you pay this liability (for example, paying tax or superannuation), you reduce the balance of this account. You can see how this works in Figure 12-2. The beginning balance of Superannuation Payable on 1 July is $1,200, and this exact amount is paid during July. During August, total credits to this account amount to $900, and you can see that the ending balance of Superannuation Payable is $900.

Figure 12-2: A payroll liability account tracks how much you owe.

Every time you generate a payroll report, remember that this report has a dancing partner hiding in the background. Or, to put this the other way around, the balance of any payroll liability account can always be matched to a corresponding payroll report.

For example, when you generate a report showing how much wages tax you owe, your PAYG Tax Payable or PAYE Tax Payable account is waiting in the wings, mirroring the information in your tax report. You can make sure that any payroll report is correct by matchmaking this report with its corresponding payroll account.

Ready to see this romance in action? Then let’s go:

1. For any payroll liability (tax, super or whatever), generate a report that shows how much you have to pay for the month or the quarter.

The mechanics of creating this report depend on what system you use. By the way, if you want more detail about how to calculate payroll liabilities, refer to Chapter 10.

2. Print a Balance Sheet for the last day of that month or quarter.

For example, if you’re paying payroll liabilities for the month of December, then print a Balance Sheet with the date 31 December. (I explain more about creating Balance Sheets in Chapter 16.)

3. Identify the liability account that you want to balance.

If you’re balancing wages tax, look at the balance of PAYG Withholding Tax Payable (Australia) or PAYE Tax Payable (New Zealand). Or if you’re balancing superannuation, check out the balance of Superannuation Payable (Australia) or KiwiSaver Payable (New Zealand).

4. Check that the balance of this liability matches against what you’re about to pay.

For example, if you calculate that you owe $900 in superannuation for the month of July, then you expect the balance of Superannuation Payable (or KiwiSaver Payable in New Zealand) in your Balance Sheet as at 31 July to be $900 as well.

If the two amounts don’t equal one another, keep reading to find out what to do next.

Troubleshooting payroll liabilities

In the previous section ‘Checking payroll liability reports’ I explain how to match up payroll reports against payroll accounts so you can be sure you pay exactly the right amount. Sounds like a plan, Stan, but what if the balance in your payroll account makes no sense whatsoever? For example, what if you think you owe $900 in superannuation for the month of July, but when you look at the balance of Superannuation Payable for the last day of July, the account balance is $2,200?

I wish I could be by your side to help you fix things in a flash. But given that astral travel isn’t in my list of personal superpowers, here’s a step-by-step troubleshooting guide instead:

1. Look up the opening balance of the payroll liability account as at the beginning of the financial year.

For example, if you’re checking that superannuation balances, look at the opening balance of Superannuation Payable or KiwiSaver Payable as at 1 July (if you’re in Australia) or 1 April (if you’re in New Zealand).

2. Check what the payment was in the first month of the financial year.

For example, look up what payments were made during July (if you’re in Australia) or April (if you’re in New Zealand). Oh yes, and make sure these payments are allocated to the correct payroll liability account.

3. Check that the opening balance matches the amount that was paid.

Does the figure you arrived at in Step 1 match the figure from Step 2? If not, you have a problem, and this problem belongs to the previous financial year (and maybe, if you’re lucky, to the previous bookkeeper!). You’re probably best in this instance to talk to the accountant.

If Step 1 matches Step 2, then your problem belongs to the current year. Keep reading . . .

4. Generate a report that shows how much was due for each payment period throughout the year.

If you pay monthly, print a report for every month. If you pay quarterly, print a report for every quarter.

5. Look at what you actually paid for each payment period.

Sometimes when I’m doing really serious troubleshooting, I create a simple spreadsheet where I show what was due in one column, and what I actually paid in another column, similar to Figure 12-3.

6. Calculate the difference between what you should have paid, and what you did pay.

Figure out why you overpaid or underpaid (similar to what I do in Figure 12-3), and if possible, make corrections to fix any errors. Any overpayments or underpayments affect the balance of your payroll liability account, and the cumulative total of these over- or underpayments should be equal to the amount that you’re out.

Figure 12-3: Reconciling payroll liabilities can be awkward, but feels good when you get it right.

Coughing up the dough

So, you’ve figured out what you owe in wages tax, superannuation and other liabilities? Alright, it’s time to hand over the cash.

In New Zealand, things are so sensible, and employers submit a single summary — the very beautiful IR345 with its companion form the IR348 — that includes PAYE tax, KiwiSaver, child support and student loans. Occasionally, you may also have other deductions to account for, such as employee loans or social club fees, but in 99 per cent of cases, the IR345 and IR348 do the job.

In Australia, government red tape is a national sport: You send PAYG withholding tax to the Tax Office; superannuation to individual employee funds (and you may end up with several different funds that you need to submit payments to); child support to the Child Support Agency; and union fees to the relevant unions. Each institution has its own forms, deadlines and procedures. Oh, what joy.

Completing your employer monthly schedule (New Zealand)

The illustrious Figure 12-4 shows a sample of an IR348 schedule. You may already know this beastie like the palm of your hand, but just in case you’re new to the game, here are a few tips:

KiwiSaver deductions are superannuation contributions an employee chooses to have deducted from their salary. KiwiSaver employer contributions are compulsory superannuation contributions that the employer has to make on behalf of the employee (see Chapter 10 for details).

I suggest you complete the IR345 and IR348 schedule as soon as you’ve processed the last pay of the month. If cashflow is tight, you can wait up until the 20th day of the following month to submit the forms and make payment. If cashflow is so tight that you simply can’t pay, submit the forms regardless and phone the IRD straightaway to let them know that payment will be late.

If you use payroll software, you can usually print up an IR345 automatically, along with the companion IR348 schedule. Alternatively you can apply to the IRD to file electronically using ir-File, the online method of submitting forms to the IRD. (Employers who collect more than $100,000 of PAYE per year must use this ir-File service.)

Before you submit the last monthly summary of the year, make sure that the whole year’s figures are spot on by following my suggested end-of-year procedures (see ‘Getting Pedantic at Year’s End’ later in this chapter for details).

Figure 12-4: Completing the monthly employer schedule.

Reporting for wages on your activity statement (Australia)

If you report for GST monthly, or your PAYG withholding tax liability goes over a certain threshold, then you must report for wages and PAYG withholding tax every month. Otherwise, you report for wages and PAYG withholding tax every quarter.

Figure 12-5 shows the wages section of a typical activity statement. W1 shows total wages, W2 shows the total of PAYG withholding tax deducted, W3 shows amounts withheld from investment distributions and W4 shows amounts withheld from suppliers who didn’t provide an ABN. In 99.9 per cent of cases, the only boxes a regular business has to complete are W1, W2 and W5.

Figure 12-5: Reporting for wages and PAYG withholding tax.

Paying superannuation (Australia)

In Australia, most workplaces are obliged to let employees choose their own super fund. For this reason, you often end up having to send off employee super contributions to a whole stack of different funds, which, to be quite honest, is a complete pain in the you-know-what.

The deadline for super comes around 28 days after the end of each quarter (in other words 28 July, 28 October, 28 January and 28 April), unless a particular award or super fund specifies that you must pay monthly. I find that paying super is fiddly, because each fund has its own form and particular submission method. Although some employers prefer to pay monthly, I suggest you keep paperwork down to a dull roar: Put the money aside for super every month into a savings account, but make payments and submit paperwork quarterly.

If an employee has been and gone before completing a super fund application, you still have to pay super for them. Phone the Superannuation Helpline on 13 10 20 and request a SHA deposit form (‘SHA’ sounds awfully like a Lion King character, don’t you think?). The only info you need is the employee’s name, date of birth and, ideally, their tax file number.

Calculating Other Payroll Expenses

Many employers have expenses relating to payroll that you don’t calculate for individual employees, but you calculate on the payroll bill as a whole. These expenses include:

Fringe benefits tax: This tax comes into play if employees are lucky enough to receive benefits in any form other than wages. See the section ‘Splitting hairs with fringe benefits’ later in the chapter for more details.

Payroll tax (Australia only): This tax kicks in when total wages for a business hit a certain threshold (anywhere between $600,000 and $1 million per year, depending on what state the business operates in). See the section ‘Hitting the payroll tax threshold’ later in the chapter for more details.

Workers compensation or accident cover: All employers need to pay accident insurance for employees. See the sections ‘Reporting for workers comp (Australia)’ and ‘Covering for accidents (New Zealand)’ later in the chapter for more details.

Splitting hairs with fringe benefits

If an employer provides an employee with a benefit that’s anything other than wages, then this sweet benevolence is called a fringe benefit. The government responds to this benevolence with unwavering severity, imposing a special tax called fringe benefits tax (FBT). (The employer is the lucky bunny who gets to pay this tax, not the employee.)

Fringe benefits come in many different shapes and sizes — limited only by human imagination — but include things like car parking benefits, cheap loans, discounted products, Christmas parties, free tickets to concerts, gifts, gym memberships, life insurance, motor vehicles for private use, prizes and school fees.

The job of submitting fringe benefits tax returns generally falls to the company accountant, but as a bookkeeper, you can make the accountant’s life a whole lot easier by keeping good records.

Chase receipts for expense payment declarations: If an employee submits an expense claim, make sure they provide a proper receipt. (An expense claim that simply says something like ‘New Dell laptop’ isn’t enough; you need the actual receipt for the computer.)

Get odometer readings and log books: Ask the company accountant if they need quarterly or annual odometer readings and/or motor vehicle log books. If so, keep on the case with employees so that they provide this information.

Maintain travel diaries: Sometimes employees have to keep travel diaries when away from home, especially if trips are part-personal and part-business. Find out what info needs to be in these diaries, and make sure employees complete their part of the deal.

When it comes to doing the books, make it easy to generate reports for the fringe benefits return by allocating transactions carefully:

Identify benefits by employee name: For example, maybe you pay life insurance premiums for three employees, and you allocate these premiums to an expense account called Employee Benefits Life Insurance. When you code each transaction, make sure to include the employee’s name in the memo so that the accountant can easily total up how much life insurance benefit each employee received.

Separate accounts: Create separate accounts in the chart of accounts for expenses that attract fringe benefits tax. For example, if the company owns two motor vehicles and one vehicle attracts fringe benefits tax because it is used partly for private purposes, but the other vehicle is 100 per cent business, separate the two vehicles into separate expense accounts.

In Australia, you must report fringe benefits on individual payment summaries if an employee receives benefits of more than $2,000 during the FBT year (1 April to 31 March). For more about payment summaries, see ‘Printing Payment Summaries (Oz Only)’ later in this chapter.

In New Zealand, the taxable value of a fringe benefit includes GST, unless the fringe benefits are GST-exempt (for example, low-interest loans, overseas travel and life insurance). You don’t report this GST on GST returns but you do report this GST on FBT returns. The payment of fringe benefits (including GST) and fringe benefits tax is an expense.

Hitting the payroll tax threshold

Payroll tax (not to be confused with PAYG withholding tax or PAYG instalment tax) is a rather perverse kind of tax that punishes businesses for getting too big and employing too many people. Payroll tax exists only in Australia and the fine print varies from state to state, but the crux of the matter is that as soon as a business pays out more than a certain amount per year in wages (ranging from $600,000 in NSW to $1 million in Queensland), the state government imposes an additional tax of between 4 and 6 per cent of the total wages bill.

Almost all businesses with a wages bill of this magnitude have some kind of payroll software, so you may well find that your software calculates the liability for payroll tax automatically. However, your job as a bookkeeper is to check that these calculations are correct.

Every state in Australia has a different dollar threshold above which payroll tax applies. Some states include subcontractors, directors’ fees and fringe benefits, others simply include straight up wages, and other states include a combination. The percentage of tax payable also varies from state to state, and the fun really starts when you have different employees working in different locations around Australia.

I’m not going to go into the fine detail of the legislation for each state — chances are it will be different by the time you read this book — but I can offer up three simple tips:

As a business grows and employs more staff, make sure you’re aware what the current wages threshold is for payroll tax. Keep checking monthly wages totals and warn your employer if wages approach this threshold.

Even if your payroll software seems to calculate payroll tax automatically, take time to double-check calculations, especially for businesses that operate in more than one state.

Double-check exactly what gets included in any payroll tax liabilities. Do you need to include directors’ fees, fringe benefits, subcontractors or superannuation?

Reporting for workers comp (Australia)

In Australia, every employer has to pay insurance premiums to cover employees in the event that they have an injury at work. This insurance is called workers compensation or workcover insurance and — make no mistake — is a big deal: If an employer doesn’t pay this insurance and someone has an accident in the workplace, the employer carries the can. (Even without an accident, the fines for non-compliance aren’t to be sneezed at.)

How workers comp works is that in the first year you make an estimate of what total wages are going to be, and the business pays an insurance premium based on that estimate. Then, at the end of this first year, you complete two forms: The first form asks you to declare what wages actually were for the year just gone; the second form asks you to make a new estimate for the year ahead.

The actual amount of the premium depends on what industry you’re operating in, how much the total wages bill is, whether employees have made any claims in the past and where you are in Australia. Also, the definition of ‘wages’ varies from state to state. In some states, wages includes many different kinds of payments, including things like fringe benefits, payments to subcontractors and superannuation.

As a bookkeeper, you may be asked to assist in completing workers compensation returns. You can make life easier for yourself, and for the company accountant, by doing the following:

Allocate contractor payments into different expense accounts, separating subbies who are covered by workers comp from subbies who aren’t.

If you’re asked to make an estimate for the next 12 months wages, start by calculating the actual results for the previous 12 months. (If you make an estimate that ends up being way less than actual wages, you could attract a penalty.)

Contact the insurance company and get it to align your insurance premium period with the financial year, so that the insurance cover runs from 1 July to 30 June. This way, you can use your end-of-year payroll reports to complete most of the information on your insurance declarations.

If the insurance period straddles financial years and you’re required to report for a previous payroll year, you may hit a situation where payroll information has already been purged. In this situation, you need to restore a backup file, and generate reports from there.

Covering for accidents (New Zealand)

In New Zealand, every employer has to pay insurance premiums to cover employees in the event that they have an injury at work. This insurance is called injury cover.

The deal with injury cover is that you register as an employer in the first year, but you don’t pay any premium upfront (although, if you’re anxious not to be hit with a big bill at the end of this first year, you can request a provisional invoice). Then, at the end of the first year, Inland Revenue reports the actual earnings of your employees to the ACC (the body that governs accident insurance). At this point, you pay two bills for ACC cover: The first bill is for ACC cover for the year just gone, and the second bill is an estimate, paying ACC cover in advance for the year ahead. (At the end of the second year, your premium is adjusted for the difference between this estimate and actual wages.)

The actual amount of the premium is based on liable earnings. Liable earnings include all wages paid to employees (up to a certain maximum threshold), and all payments made to subcontractors who don’t have their own accident cover.

As a bookkeeper, you may be asked to assist in completing annual returns. You can make life easier for yourself, and for the company accountant, by separating contractor payments into different expense accounts, grouping together all contractors who don’t have their own accident cover into their own expense account.

Getting Pedantic at Year’s End

When the end of the financial year rolls around (that’s 30 June in Oz, and 31 March in NZ), the fun really begins. Now is time to check that everything to do with payroll is completely spick and span, and you’re just the person for the job:

1. Print up a report showing total wages paid and total PAYG/PAYE tax deducted.

How you do this depends on whether you use payroll software or not, but the aim of the game is to go to your payroll reports, your wages spreadsheet or your handwritten wages book and total up both wages and tax for the year.

2. Compare total wages in your payroll records against total wages in your Profit & Loss report (the two figures should be the same!).

Compare the total for Wages Expense on the Profit & Loss report against total wages on your payroll report. If the two reports don’t match, run the reports month by month until you identify the difference. (The most common cause of error is if someone allocates an employee’s wage directly to Wages Expense without processing the transaction correctly in payroll.)

By the way, if you do books by hand, you may have one total for net wages and another for wages tax. The figure that appears on your Profit & Loss report in Wages Expense should be the grand total of the two.

3. Balance all payroll liability accounts, including PAYG/PAYE tax and superannuation.

I explain how to balance payroll liabilities earlier in this chapter, in the section ‘Checking payroll liability reports’.

4. Double-check that all payroll clearing accounts have a nil balance.

If you have an Electronic Clearing Account or Payroll Cheque Account, make sure the balance of these accounts is nil at the end of the year. (I talk more about reconciling clearing accounts in Chapter 11.)

5. Reconcile your main business bank account up to the last day of the financial year.

When you reconcile, pay special attention to any uncleared employee payments — these could be duplicate transactions and cause problems with your payroll reports.

6. Finalise your end-of-year payroll reports.

In Australia, you print payment summaries for each employee (see ‘Printing Payment Summaries (Oz Only)’ for more details). In New Zealand, you simply submit your final IR345 and IR348 forms for the year. However, I recommend that you also print and distribute a Certificate of Earnings for each employee for the whole year.

7. Send your end-of-year reconciliation off to the Tax Office (Australia only).

In Australia, you polish off the year in style by sending the Tax Office a summary of all the payment summaries given to employees (you can submit this report either electronically, on a CD, or via a handwritten report). This report is due by 14 August each year.

8. Back up.

If you’re using payroll software or a spreadsheet (as opposed to handwritten books), make a special backup of all your payroll data onto a CD, DVD, removable hard drive or flash drive. Name this file clearly saying ‘End-of-Year Payroll’ followed by the year.

Once you’ve made one backup, make an extra backup just in case. Label both backups clearly and store them in safe, separate places, with one backup set kept off-site. Note that end-of-year payroll backups need to be kept in a safe place for a minimum of seven years.

Printing Payment Summaries (Oz Only)

When winter sets in, the blue skies get bluer and the soccer season starts to reach a climax, you know the time has come: Tax return mayhem. Your role in this racket is to provide every employee with a report showing total wages paid and total tax deducted for the past 12 months. This report is called a payment summary and is due by 13 July each year.

If you have payroll software, the easiest approach is to print payment summaries direct from the software. Otherwise, contact the Tax Office and ask it to send you the necessary paperwork. Although completing these payment summaries is pretty straightforward, I’m going to help out with a few tips:

You’re going to need tax file numbers and full mailing addresses for every employee, and some software doesn’t let you complete the process of printing payment summaries for any employee until every employee has these details (what sadistic computer programmer dreamt up that little hurdle, I wonder?). So get prepared in June, and check you have all these details ready to go.

Always check your books for the year before finalising payment summaries (refer to ‘Getting Pedantic at Year’s End’ earlier in this chapter for details).

Keep a copy of every payment summary, as every year, there’s always one dumb bunny who loses this precious document.

Employee allowances are tricky — some allowances are meant to be included in gross payments, others are meant to be listed separately and a few kinds of allowances aren’t meant to be shown on payment summaries at all. If you’re at all unsure, check out the relevant pages at www.ato.gov.au or ask the company accountant for guidance.

Don’t forget that as well as giving a payment summary to each employee, you need to send a summary of the summaries to the Tax Office by 14 August each year.

Meeting Minimum Pay and Conditions

In both Australia and New Zealand, employers are obliged to offer employees certain minimum pay and conditions such as annual leave, sick and carers’ leave (also known as personal leave in Australia or domestic leave in New Zealand), additional loadings for casual employees and so on. Employers also have to comply with minimum conditions, such as the number and arrangement of hours that employees are required to work. Minimum pay and conditions vary depending on where your business is located and the industry in which you’re operating.

The main thing to be aware of is that the onus is on the employer (rather than on the employee) to understand what the minimum legal pay and conditions are. If you’re the bookkeeper who’s responsible for wages, the employer may delegate this responsibility to you (unless, of course, you’re the business owner and the bookkeeper, in which case you can behave like a true small business person and delegate this job to yourself!).

Applying the law (Australia)

In Australia, industrial relations have been a political hot potato for several years now. Until recently, a mix of state and federal legislation applied to Australian workplaces, with state legislation applying to sole traders and partnerships, and federal legislation to companies. However, with the exception of Western Australia, all states have now either moved or are moving to federal legislation.

With this continuous change in mind, I start with a clear caveat: At the time of writing, my information is up to date. However, the onus is on you to double-check that what you read here still applies.

1. Check that Fair Work Australia is the correct source of information.

At the time of writing, if you’re a company structure or you operate from any state other than Western Australia, contact Fair Work Australia (phone 13 13 94 or visit www.fairwork.gov.au) for information about pay scales and employment conditions. However, you may want to check with your industry association or local chamber of commerce that this reference is still correct.

If you’re a sole trader or partnership based in Western Australia, visit www.docep.wa.gov.au or phone 1300 655 266 for information about pay scales and employment conditions.

2. Review the pay, leave and conditions that apply to your industry.

Go to the Pay, Leave and Conditions page at www.fairwork.gov.au and search for the award relevant to your industry. Be careful to read the coverage provisions to ensure that you’re referring to the correct document, and seek further advice if you’re not sure.

This award is a payroll officer’s ‘bible’. Print this document out and read it from front to back. Whenever you have a query about an employee’s pay, remember that this award is your primary reference.

3. Check that your workplace complies with National Employment Standards.

The National Employment Standards (NES) provide a safety net that outlines ten minimum entitlements for all Australian employees, including maximum weekly hours of work, parental leave, annual leave and so on.

The beady-eyed among you may spot that this document refers to minimum entitlements. Beware: Certain industry awards require you to provide more generous conditions than those described in the NES.

Don’t be hoodwinked into thinking that an employer is okay to pay above the minimum for some things and below the minimum for others, justifying this juggling act by saying the two cancel each other out. The only time trading pay or benefits is okay is if an employer negotiates some kind of registered workplace agreement, and registers this agreement with the relevant industrial relations body.

Applying the law (New Zealand)

New Zealand workplaces have blanket coverage by many Acts of Parliament, and too many employment-related Acts (around forty) to list here. However, as a pay officer, you need to be aware that the Employment Relations Act, the Holidays Act and the Minimum Wage Act form the backbone of any employment relationship.

The Employment Relations Act: The goal of this legislation is to build productive employment relationships through mutual trust, confidence and fair dealing. The principle of good faith underlines the key spirit of the Employment Relations Act, which seeks to promote positive dealings between employees, employers and unions.

The Holidays Act 2003: The Holidays Act 2003 governs entitlements for annual holidays, public holidays, sick leave and bereavement leave.

The Minimum Wage Act: The purpose of this Act is to provide for minimum wages and a maximum working week. By law, employers must pay at least the minimum wage, even if an employee is paid by commission or by piece rate. The minimum wage applies to all workers aged 16 years or older, including home workers, casuals, temporary and part-time workers.

Set against the context of these Acts, the main thing to be aware of is that every employee must have a written employment agreement. This agreement can be an individual employment agreement (a one-to-one agreement, between the employer and the employee), or it can be a collective agreement (an agreement between the employer and all the employees).

When working out these agreements, some stuff has to be included, such as the place of work and working hours, and also some minimum conditions must be met (regardless of whether these conditions are in the agreement or not), such as annual holidays and sick leave. An employer can also add additional entitlements to an agreement, even if they’re not required by law.

For assistance with drafting an employment agreement for your workplace, head to www.ers.dol.govt.nz where a nifty little tool called the Employment Agreement Builder makes the whole process surprisingly swift and easy.

As a bookkeeper, it’s not really your responsibility to nut out employment agreements with employees (unless you’re also the business owner, of course). However, once an agreement is in place, it’s your job to be familiar with this agreement so that you can make sure that employees are paid the agreed rates, receive the right amount of leave and so on.