Chapter 3

Going for the Big Equation

In This Chapter

Revealing the inner life of Pacioli (makes Isaac Newton seem tame)

Putting a little loving back in the air — pairing up those debits and credits

Taking a peek into the inner workings of accounting software

Choosing between hand-to-mouth cash and high-tech accrual

If you want to be a racing driver, it pays to understand something about the mechanics of a car. If all you want to do is drive from A to B, then you can rely on others to bail you out, and go from one year to the next without looking under the bonnet.

The same goes for bookkeeping. If you’re a business owner and you want to do your books in a simple fashion, giving them to your accountant for the finishing touches, then you can get by without ever worrying about double-entry bookkeeping. (Yep, you’re off the hook — you can skip reading this chapter and proceed to the more interesting stuff.)

However, if you’re serious about bookkeeping, the theory of how bookkeeping works and what goes on behind the scenes is vital. An understanding of debits and credits — which form the bones of double-entry bookkeeping — is essential for many of the more skilled activities a bookkeeper undertakes, such as adjusting accounts via journal entries, making sense of a Balance Sheet or troubleshooting account balances.

In this chapter, I explore all the ins and outs of double-entry bookkeeping, and how to figure out debits and credits for most everyday transactions. I also talk about the difference between cash and accrual accounting, and how to choose which system is going to work best for you.

Matchmaking with Debits and Credits

Way back in the distant mists of time, over 500 years ago, an Italian mathematician by the name of Pacioli wrote a rave about bookkeeping, culminating in a brilliant equation that falls only one step short of Einstein’s theory of relativity. The equation goes:

Assets = Liabilities + Owner’s Equity

Pacioli expanded on this formula by articulating that all asset, cost of sales and expense accounts are debit balances, and all liability, equity and income accounts are credit balances. This leads to Paco’s second equation:

Debits = Credits

Pacioli’s idea was that for every financial transaction that takes place, there’s both a debit and a credit. Just like yin and yang, man and woman, property developer and politician.

Sounds a little bizarre, right? Read on to put theory into practice.

Studying a little give and take

So, every transaction in accounting is either a debit or a credit. A debit is any transaction that increases assets or expenses, or that decreases liabilities, equity or income. A credit is any transaction that increases liabilities, equity or income, or that decreases assets or expenses.

Table 3-1 provides a summary of debits and credits in action.

|

Table 3-1 Debits and Credits in Action |

||

|

Account Type |

To Increase This Account |

To Decrease This Account |

|

Asset |

Debit |

Credit |

|

Liability |

Credit |

Debit |

|

Equity |

Credit |

Debit |

|

Income |

Debit |

Credit |

|

Expenses |

Debit |

Credit |

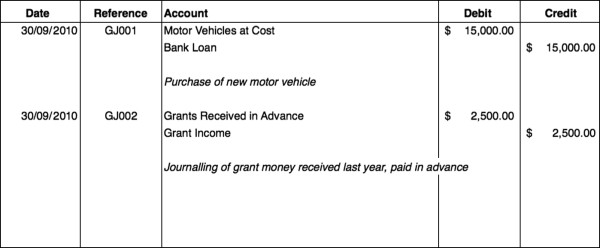

Bookkeeping journals generally have five columns and at least three separate lines per transaction: On the first line you write the date, reference number and account name being debited, plus an amount in the debit column on the left; on the second line you write the account being credited, plus an amount in the credit column on the right; and on the third line you write a short memo describing the journal. Figure 3-1 shows how this works. (Note: This example is simplified for the purposes of my example, and doesn’t include GST.)

Figure 3-1: A journal entry includes a column for debits on the left, and a column for credits on the right.

This journal may look peculiar, but the concepts to remember are as follows:

Debits are on the left, and credits on the right.

Whenever you allocate an entry to an asset account that increases the balance of this account, you put the amount in the debit column. (This means, incidentally, that if you increase your bank account, this is a debit, not a credit. Weird, heh?)

Whenever you allocate an entry to a liability account that increases the balance of this account, you put the amount in the credit column.

When you pay out an expense, the expense goes in the debit column.

When you receive money, the income goes in the credit column.

Following a modern fable

Debits and credits in accounting are strange to get your head around, but an example helps to bring these weird principles to life. Say Jamie receives $5 from his mum to buy some lemonade. Jamie, being just a tad on the nerdy side, asks himself, what are those rules again?

Assets = Liabilities + Owner’s Equity

and

Debits = Credits

Jamie muses for a while and applies this rule to his business venture so far. He has assets of five bucks, so he debits his cash account. And his stake in the business is the same amount, so he credits his equity account.

Assets in cash $5 = Liabilities (none) + Equity (capital contributions) $5

Jamie then scrounges $2 from his dad. Dad is grumpy and says this is a loan only. Applying his accounting principles, Jamie debits his cash account and credits his liability account. He now has

Assets in cash $7 = Liability $2 + Equity (capital contributions) $5

Jamie then plays truant from school and buys seven bottles of lemonade for $1 each. He runs off to the protest march in town, where he sells each bottle at $1.50. With this transaction, he increases his cash (a debit), and increases income (a credit). He returns home with $10.50 in his pocket, having made a profit of $3.50. Jamie now has

Assets in cash $10.50 = Liability $2 + Equity $8.50 (capital of $5 and current earnings of $3.50)

At this point, Jamie’s Profit & Loss report shows income of $10.50, cost of sales of $7 and a profit of $3.50. Note that the profit at the bottom of the Profit & Loss report is the same figure as current earnings in the Balance Sheet.

So there you have it: An explanation of debits and credits and why a Balance Sheet always balances.

Putting Theory into Practice

In this section, I explain how to put debits and credits into practice using everyday transactions such as sales, customer payments and supplier payments.

Here’s my fail-safe method (ignoring GST):

1. Decide what accounts are involved.

Don’t forget you often get more than two accounts in a single transaction, especially if GST is involved.

2. For each account involved in this transaction, decide what kind of account it is.

Are the accounts assets or liabilities, income or expenses? If you’re not sure, refer back to Chapter 2 for an explanation of every account type.

3. Decide whether the balance of these accounts is increasing or decreasing.

For example, if you pay money out of your bank account, the balance of your bank account goes down, and the balance of whatever expense account is affected goes up.

4. Figure out whether you need to debit or credit each account in order for your transaction to make sense.

Table 3-1 to the rescue. For example, to decrease the balance of your bank account, you need a credit, and to increase the balance of an expense account, you need a debit.

5. Record your transaction.

Earlier in this chapter, Figure 3-1 shows a typical journal entry, with information about the accounts that you’re debiting and crediting, as well as a date and a reference number.

6. Check your work.

If a journal entry affects a bank account, one easy way to check your work is to make sure your bank account reconciles (for more about bank reconciliations, see Chapter 11).

Clear as mud? Read on to see how I apply my fail-safe method to several different kinds of transactions.

Moving funds in bank accounts

A friend asked me the other week ‘What’s the definition of an accountant?’ ‘Tell me’, I replied hesitantly. (My friend is actually married to an accountant, a man with a rather lugubrious temperament reminiscent of Eeyore in Winnie the Pooh.) ‘An accountant’, my friend replied in a rather despairing tone, ‘is someone who solves a problem you didn’t know you had in a way you don’t understand.’

To be sure, this whole business of applying debits and credits feels rather counter-intuitive at times. For example, if I deposit money into my bank account, I think to myself, ‘Cool, my account is in credit now’. But in fact, if I see life from a warped accounting kind of perspective, what I’ve done is increase the value of an asset. Looking at Table 3-1, if you increase an asset, this action creates a debit. And indeed, accountants consider an increase in your bank account as a debit, and a decrease as a credit. Yep, the complete opposite of what you expect.

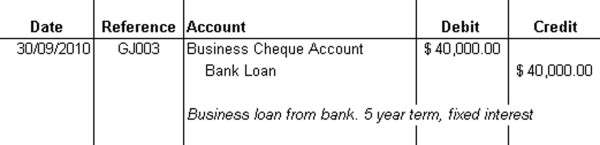

To try and clear up any confusion, I’m going to work through a detailed example, imagining that I’ve just received a loan for $40,000.

1. What accounts are involved?

With this transaction, I end up with $40,000 more in my bank account, but I also end up with a loan for the same amount.

2. What types of accounts are affected?

Easy. My bank account is an asset (well, on a good day it is), and this new bank loan is most definitely a liability. (Just how badly do I need that new ute, I ask myself.)

3. Is the balance of these accounts increasing or decreasing?

My bank account is increasing, and so is the loan account.

4. Do I need to debit or credit each account in order for this transaction to make sense?

Looking at Table 3-1, if an asset increases, that’s a debit. If a liability increases, that’s a credit. Ah, how sweet. A debit and a credit, like lovers on a moonlit night. You can see my journal entry in Figure 3-2.

Figure 3-2: Recording a general journal entry for a new loan.

Taking a peek at sales

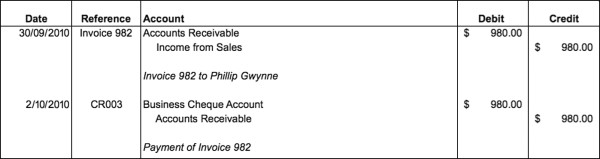

Okay, I’m going to apply the whole debits and credits method to a sales transaction where I sell goods to a customer on credit and then a few days later, the customer pays.

Using the method from earlier in this chapter (refer to ‘Putting Theory into Practice’), here goes:

1. Decide what accounts are involved.

I’ll keep things simple and assume no GST is involved. So the two accounts involved are Accounts Receivable (the money that customers owe me) and Income from Sales.

2. Decide what type of accounts these are.

I could refer to Chapter 2 for help with this one, but I just happen to know that Accounts Receivable is an asset, and Income from Sales, well, income is an income account. (Something has to be easy.)

3. Decide whether the balance of these accounts is increasing or decreasing.

Accounts Receivable is going to increase, because customers are going to owe me more after the sale. Income from Sales is going to increase also, because I’m making a sale.

4. Figure out whether you need to debit or credit each account in order for your transaction to make sense

Aha. I look at the handy info in Table 3-1, which tells me that if Accounts Receivable increases, that’s a debit, and if Incomes from Sales increases, that’s a credit. Yeehaa! I’ve got a debit and a credit, so I know things are going to balance.

5. Record your journal.

See the first journal in Figure 3-3 for how this sale appears.

Figure 3-3: Two journal entries — one showing a sale, the other showing a payment.

Next, imagine I receive the money from this customer. This time, I know that Accounts Receivable and my Business Cheque Account are the two accounts affected. Accounts Receivable is going to decrease (and Table 3-1 tells me that a decrease in an asset is a credit), and the balance of my Business Cheque Account is going to increase (and I can see that an increase in an asset is a debit). The second journal in Figure 3-3 shows this payment in action.

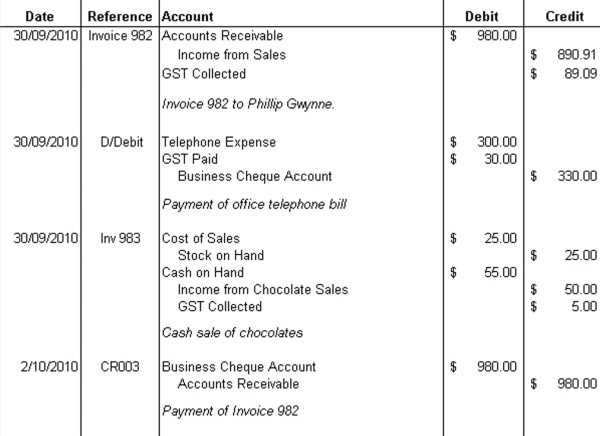

Checking out expenses

Okay, so what are the journal entries behind an expense payment, such as paying a telephone bill?

Using my step-by-step method, figuring out that your Business Cheque Account and your Telephone Expense account are the two accounts involved is easy. Your Business Cheque Account is an asset and the balance of this account is going to decrease. If assets decrease (refer to Table 3-1), this is a debit. Telephone is an expense account and the balance of this account is going to increase. When expenses increase, this is a credit.

Another debit, another credit. Figure 3-4 shows how it works.

Figure 3-4: The journal entry behind the payment of a telephone account.

Viewing stock movements

Stock movements are the hardest of all to understand with debits and credits because there are almost always more than two accounts involved. I talk more about inventory in Chapter 13, but for the sake of completeness, I also describe the debits and credits behind a simple stock movement transaction in this chapter.

In this example, I’m going to work out the debits and credits for selling a box of luscious dark chocolates (beats widgets as an example, any day). The sell price is $55, paid in cash, and the chocolates cost $25 to buy.

1. Decide what accounts are involved.

I know my Cash on Hand account is going to go up by $55. I also know that my Stock on Hand is going to decrease and I have to show a figure in my Profit & Loss for the amount that the chocolates cost me.

2. Decide what type of accounts these are.

My Cash on Hand account is an asset. Income from Chocolate Sales is an income account and the cost of the chocolates is a Cost of Sales account. Stock on Hand is an asset account. (For more about account types, head back to Chapter 2.)

3. Decide whether the balance of these accounts is increasing or decreasing.

My Cash on Hand account is going to increase, as will my Income from Chocolate Sales account and the balance of my Cost of Sales account. My Stock on Hand account is going to go down.

4. Figure out whether you need to debit or credit each account in order for your transaction to make sense

Table 3-1 comes to the rescue once more. See Figure 3-5 for how the debits and credits work out. By the way, at the end of this transaction, I’m left with $30 in my Cash on Hand account, which matches exactly with the amount of cash in my hot, sticky hands.

Figure 3-5: Recording a journal entry for a sale of a stock item.

Throwing GST into the mix

So far, I’ve been keeping my examples pretty simple, because I want to demonstrate the logic of double-entry bookkeeping. However, things do get more complicated when you pop GST into the mix.

From a bookkeeper’s perspective, when you add GST to a sale or a purchase, this tax doesn’t affect the amount of income or expense. For example, if you make a sale for $90 and you add GST to this sale, then the GST component isn’t income, rather this component is tax owing to the government. In Australia, where GST is 10 per cent, the income on this sale is $90, with $9 GST.

In Figure 3-6, I show the transactions from Figures 3-3, 3-4 and 3-5 one more time, but I include GST on each transaction. (Note: I use the Aussie rate of 10 per cent in this example.) When I record a sale, I credit an account called GST Collected. When I record purchases, I debit an account called GST Paid. (I generally keep GST accounts separate, with one account for GST Collected and another for GST Paid. Some accountants prefer to use a single tax account called Tax Payable. Either method works fine.)

Figure 3-6: Journal entries showing GST in sales and purchase transactions.

Playing the Double-Entry Game with Accounting Software

I mention right at the beginning of this chapter that if you use accounting software, you can get by as a bookkeeper for years without understanding debits and credits. I’ve worked with many very good bookkeepers who are great at their jobs, but fall to pieces when asked to analyse why debits match credits, or whether an increase in the bank account should be a debit or a credit.

Why is this? Well, if you use accounting software, you don’t have to worry about which side of a transaction is a debit or which is a credit. For example, with most accounting software, if you record the payment of a telephone bill, you go to a menu such as Write Cheques or Spend Money, then select the bank account and choose the kind of expense. The software decides where the debits and credits go.

Sales work in a similar fashion. When you record a sale, you simply enter the customer name and an income account. The accounting software selects the debit side of the transaction (accounts receivable in this example) automatically.

In this next section, I explain how accounting software decides what account to debit, and what account to credit. I also share a couple of tips about viewing the debits and credits behind any transaction, and about recording general journal entries.

Stealing a look behind the scenes

The deep thinkers among you are probably wondering how accounting software decides what’s a debit and what’s a credit. The answer to this question depends on what software you use.

With MYOB, you can view the set-up behind debits and credits by going to the Setup menu and selecting Linked Accounts. In the Linked Accounts menu for sales, you can select the asset account that tracks links to accounts receivable, the income account that links to freight collected, the expense that links to discounts taken, and so on.

If you don’t have accounting or bookkeeping training, you can create a lot of problems if you choose an inappropriate account type for a linked account in MYOB. If you’re not sure whether you should edit a linked account, you’re best to talk to your accountant or leave the existing account alone.

QuickBooks works in a slightly different manner. When you set up your Chart of Accounts, you select an Account Type for each account. You can only select Accounts Receivable as the Account Type for one account, and so QuickBooks knows where to put the debit and credit side of sales and customer payments. Similarly, you can only select Accounts Payable as the Account Type once.

Drilling down to the debits and credits

If accounting software is so smart, figuring out debits and credits on your behalf, how do you check out the debits and credits behind a transaction? I explain how to look this info up in MYOB and QuickBooks, but chances are that if you use different software, similar principles apply.

To see the debits and credits behind any transaction in MYOB, first display the transaction and then go to the Edit menu and select Recap Transaction. This command takes you to the transaction journal, with the debits and credits displayed line after line.

To view the debits and credits behind any transaction in QuickBooks, display the transaction and then click the Journal button. This command takes you to the transaction journal, with debits and credits displayed in all their finery.

Recording general journals

If you’re working with accounting software, then you rarely need to record a general journal that requires you to allocate the debits and credits behind a transaction. Typically, the only time you use general journal entries is if you record a transaction that doesn’t affect a bank account, such as a depreciation journal or a year-end adjustment. (I cover the debits and credits behind almost every kind of general journal in Chapter 14.)

If you’re unsure about whether something should be a debit or credit (even after reading all my wonderful advice on this topic), then don’t stress. Simply record the journal, making your best guess as to what’s what. Then, after you’ve done the journal, look at the ending balances of the affected accounts and see whether they look correct. If not, return to the journal, swap the debits and credits around, and then resave your transaction.

When recording general journals, take a moment to consider how GST is going to be affected. For example, in MYOB you click a button to indicate whether this journal gets reported as a sale or as a purchase on GST reports. Similarly in QuickBooks, you have to select the correct Tax Item on every line, as this choice also affects how this transaction appears on GST reports.

Choosing between Cash and Accrual

Before you start to do your books, you need to decide whether you’re going to do your books on a cash basis or an accrual basis, or a combination of both. (Cash-basis accounting offers a simpler and faster approach to bookkeeping, but accrual accounting offers more accurate management of information.) This choice of accounting method affects the way you record everyday transactions.

By the way, cash-basis accounting, despite a rather dubious ring to its name, is nothing to do with Mafia characters exchanging wads of cash in the dead of night. Rather, cash-basis accounting is a perfectly respectable way to do your books. Why? Read on . . .

Keeping things simple with cash

With cash-basis accounting you recognise income only when you receive cash from a customer or pay cash to a supplier. For example, if you sell something on credit, you don’t record this sale as income at the point you send the customer an invoice. Instead, you record this sale as income when you receive the dough in your hot, sticky hands.

The same principle applies to purchases. You may receive a bill from a supplier and hold onto it for a couple of weeks before paying it. With cash-basis accounting, you don’t record this purchase as an expense at the time you receive the bill. Instead, you record this purchase as an expense when you finally part with the cash.

I use cash-basis accounting for my holiday house business. Guests often pay in advance, some pay at the time, other guests even pay after their stay. However, I don’t bother creating an invoice for every transaction. For bookkeeping purposes, I simply get my bank statements and whenever I see money going into my account, I record it as income. (I don’t even record the name of the person who paid.) In the same way, I don’t worry about recording any bills I owe to suppliers. Only when the money goes out of my bank account do I record the expense in my books.

Cash-basis accounting works well for businesses that don’t offer credit to customers, and that don’t have a lot of money owing to suppliers. Here are some examples where cash-basis accounting works well:

A client of mine makes glass bead jewellery that she sells at markets on weekends. Her books are simple: She banks her takings every week and records this as income, and records expenses only when the money leaves her bank account.

Another client is a dentist. He has medical software that keeps track of patient accounts, and so for his bookkeeping, he keeps things simple. He records daily banking by referring to his bank statement, allocating the totals to a single income figure, and records payments to suppliers only when bills are paid.

A friend of mine is a handyman. He provides handwritten dockets to his customers on the spot as he finishes each job, and he uses copies of these dockets to keep track of which customers have paid and which haven’t. For his bookkeeping, he simply works from his bank statements, recording weekly banking totals and allocating them to income. Similarly, he only records supplier bills in his books when he makes the payment.

The ease of cash-basis accounting works well for small businesses getting started. However, if you want to track how much customers owe you, or how much you owe to suppliers, then accrual accounting works better.

Getting more info with accrual

With accrual accounting, you recognise income at the time the sale occurs, regardless of when you receive cash from a customer. Similarly, you recognise expenses at the time you receive a bill from a supplier, regardless of when you pay this bill.

If you use accounting software, and you take advantage of the sales or purchases features, then you automatically do your books on an accrual basis. Unless you specifically ask for a cash-basis report, the financial reports in accounting software report income at the time you make a sale, not when you finally receive payment for it. Similarly, reports show expenses at the time you receive goods or services, not when you finally make a payment.

Accrual accounting works well for businesses that offer credit to customers, and that receive credit accounts from suppliers.

Accrual-based bookkeeping is the most accurate from a management accounting perspective as it produces the most accurate Profit & Loss reports. However, accrual-based bookkeeping usually takes longer than cash-based bookkeeping, so as a bookkeeper, you need to be confident that the extra time taken warrants the improved quality of information provided.

Enjoying a half-half measure

Sometimes it makes sense to use cash-basis accounting for sales and accrual accounting for purchases, or vice versa. For example, many businesses use accounting software to record individual customer sales (accrual accounting), but only record supplier bills as they’re paid (cash-basis accounting).

With my consulting and writing business, I combine cash and accrual accounting. I use accrual accounting for billing my customers, recording invoices in my accounting software as soon as work is complete, even though my customers may take weeks (or even months!) to pay. I use cash-basis accounting for my suppliers, only recording expenses in my accounting at the point I pay suppliers.

Remember that for tax purposes (as opposed to bookkeeping purposes), you can only use one method or another. For example, although I do my books on a cash basis for my suppliers and on an accrual basis for sales, when I lodge my tax return, I declare both income and expense on a cash basis. To do this, I make a journal entry once a year that adjusts my income to reflect cash received, rather than sales billed. (Skip to the next heading for more about accounting for tax purposes.)

Using one method for your books, and another for income tax

In some situations, it’s okay to have a disparity between your bookkeeping method and your tax accounting method. For example, some businesses use cash-basis accounting for everyday bookkeeping, but use accrual accounting for lodging tax returns. That’s okay — once a year, the bookkeeper can make a list for the accountant listing all the bills owing to suppliers or money owing from customers. The accountant can then do an adjustment, converting a set of cash-based books to an accrual-based set of books. This scenario is likely for many small businesses.