The topic of security awareness has exercised academics and practitioners for well over 20 years. A search for articles on ‘information security awareness’ and ‘cybersecurity awareness’ using Google Scholar, for example, yields over 3,300,000 results at the time of writing,33 while an Amazon search presents over 200 books. International and national standards such as ISO/IEC 27001, ISO/IEC 27021, NIST SP 800-50 and proprietary standards such as the ISF Standard of Good Practice and ISACA COBIT 5 for information security, devote all or part of their contents to cybersecurity awareness and associated material. Innumerable presentations have been given on the topic by practitioners, academics and consultants; and there is a thriving industry offering awareness programmes, content, guidance on running programmes, and tools to help the cybersecurity professional deliver better programmes, better content and achieve the hoped-for results.

And of course, this outpouring of research, literature, knowledge and experience is still growing. So, why add to this voluminous collection of knowledge?

Simply, we believe there is a way to do things much better. Rather than focus on awareness on its own, we believe that a different approach is needed. We call that different approach the ABCs. Our approach links awareness, behaviour and culture together, so that each reinforces the other: awareness campaigns are designed to change behaviour for the better; better behaviour translates into cultural norms; cultural norms maintain awareness and set expected behaviours.

WHERE ARE WE TODAY?

Despite the outpouring of knowledge and expertise, and the efforts and resources expended on security awareness, the general perception is that cybersecurity awareness is, to a great extent, not delivering. The desired objectives, for example that employees will ‘think security’ or that a security culture will be created, are rarely, if ever, achieved. Instead it still seems as though individuals frequently click on malicious links in emails, more incidents occur or the security professional is pushed further away from the business. The timing of awareness programmes, often delivered when people join and then refreshed annually, seem to militate against building understanding and commitment to cybersecurity and are often submerged under day-to-day issues, change programmes and all the demands on an individual’s time at work. There is also the issue of getting time in front of employees – an awareness programme has to slot into the schedule of corporate events, communications and training. Unfortunately, as many cybersecurity professionals can attest, cybersecurity is placed low on the list, behind many other corporate communications.

But how did we get here? Why, despite all the money, time and brainpower thrown at security awareness, are we still seeing the same problems and results?

There are probably as many reasons as there are stars in the sky, but there are several that seem to crop up time and time again, which are:

- myths of awareness;

- unclear objectives;

- delivery;

- problem exists between chair and keyboard;

- focusing on ourselves alone.

In this chapter we’ll examine each of these reasons in turn.

MYTHS OF AWARENESS

There are many myths about cybersecurity awareness. The top five are listed below:

- Cybersecurity is everyone’s responsibility.

- Cybersecurity is important to employees.

- Cybersecurity awareness will turn everyone into a ‘human firewall’.

- Cybersecurity awareness will make everyone behave in the way we want.

- Cybersecurity awareness will turn into a security culture.

Let’s start exploding these myths with number one in our list. Unfortunately, information security, despite what we think as cybersecurity professionals, isn’t everyone’s responsibility. For most organisations, it’s the responsibility of the security team, in the same way that invoices and payments are the responsibility of the finance team. If it was the employees’ responsibility, then they would have been employed to do cybersecurity – not the position they currently hold.

There is also the perception that the information employees use in their jobs is the organisation’s information, not their information, so protecting it isn’t their problem: it’s the organisation’s responsibility to protect it.

The second myth is that cybersecurity is important to employees. As has been repeatedly demonstrated, employees are happy to give their work password for a chocolate bar;34 sell information from their current employer for quite small sums; or use their corporate email to create accounts and login to dating (and other, ahem, interesting) sites.35 Getting through the day, their daily tasks, getting paid, getting promoted, getting recognised and thanked are all much, much more important to employees than not clicking on suspicious looking links or checking email meta-data. Of course, cybersecurity is important to us; that could be why we do the jobs we do, but for the vast majority of people cybersecurity is low on the list of priorities and interests. There have been attempts to link cybersecurity to staff performance reviews and bonuses, to spur interest and attention. The jury is still out on these initiatives: at issue is how little cybersecurity can be linked to business performance and, of course, finding fault and tracing business impact back to an individual.

The term ‘human firewall’ has become very popular and is used by a number of security companies at the time of writing. No doubt the term will pass out of favour and be replaced by something similar. Our third myth, regardless of the words, is that once employees have received their cybersecurity awareness training, they will return to their desks and devices and stop everything that looks like a phishing email, dodgy attachment or piece of malware (never mind that real firewalls don’t always stop such traffic). Training of any sort confers a ‘halo effect’ and people go back to work keen and full of good intentions, which are then lost as the daily grind of meetings, emails and work-related activities resumes. Even with reminders and follow-ups, the impact of the training is lost. So, our human firewalls – although I’m not sure people would like to be labelled as such – may start with the best of intentions but over time their effectiveness lessens and can return to pre-training levels.

Our penultimate myth is that awareness can change behaviour and make everyone behave in the way we want or behave just as we cybersecurity professionals do. Many organisations expect certain patterns of behaviour (and actively encourage employees to align with those expectations) and, if the desired cybersecurity behaviours are discordant, then they will be ignored and rejected.

On the other hand, we should also be mindful that we don’t want everyone to become suspicious, mistrustful and paranoid of every single email or website, believe that every attachment is malicious, nor do we want everyone in the organisation to ‘think like a hacker’; if nothing else, the helpdesk could be inundated!

The last myth is that we can create a security culture by awareness alone. Roughly defined, culture is ‘the way we do things around here’ and is made up of many factors. I like the cultural web (Johnson et al., 2012), which highlights the importance of six factors in creating or reinforcing a culture. The cultural web, simply, indicates that many factors influence and shape culture. Each factor, on its own or in concert with others, can influence the culture and can contribute to maintaining that culture as well. The six factors are:

- stories and myths;

- rituals and routines;

- symbols;

- organisational structure;

- control systems;

- power structures.

This is not the only model of culture – Geert Hofstede and his collaborators have for many years looked at culture across and in multinational organisations and produced some very insightful findings (see Hofstede et al., 2002, 2010).36 What the cultural web neatly illustrates is that culture is made up of many interrelated and interlocking factors and that they may have to be addressed simultaneously to start the process of changing or building a culture.

An organisation will often have more than one culture; sometimes these are cultures influenced by location, by professional or commercial grouping or by technical expertise. Good examples are the difference between sales and finance functions, or US and European offices. Each of these cultures is built up over time and reinforced by the people who work in those cultures. Culture is ‘sticky’ in that as people join a company, they are exposed to that culture and start to behave in a manner the culture and people expect. That’s why changing culture is often so difficult – it requires people to change their mindset and their behaviours. The reason why we need to explode this myth is that culture change and a security culture will not spring into existence because of a set of phishing emails or a couple of hours of awareness training a year: it requires much more than this.

While we have the eventual aim of creating a security culture, we should consider how we can build towards that goal. That means we have to revise our objectives and ask ourselves a simple question: ‘what are we trying to achieve?’, which is the next topic we cover.

WHAT ARE WE TRYING TO ACHIEVE?

Take a step back and think about your latest awareness programme. What were you trying to achieve? What did you want the programme to achieve? What did your boss want the programme to achieve?

We need to go further back than this and understand what we mean by awareness. All too often, we don’t present an awareness programme; we present a mix of awareness, training and education, dressed up as ‘awareness’. Confusing these three terms – awareness, training and education – and their objectives means that a clear message or path to understanding can be obscured or lost, making the whole exercise deeply unsatisfying for all concerned.

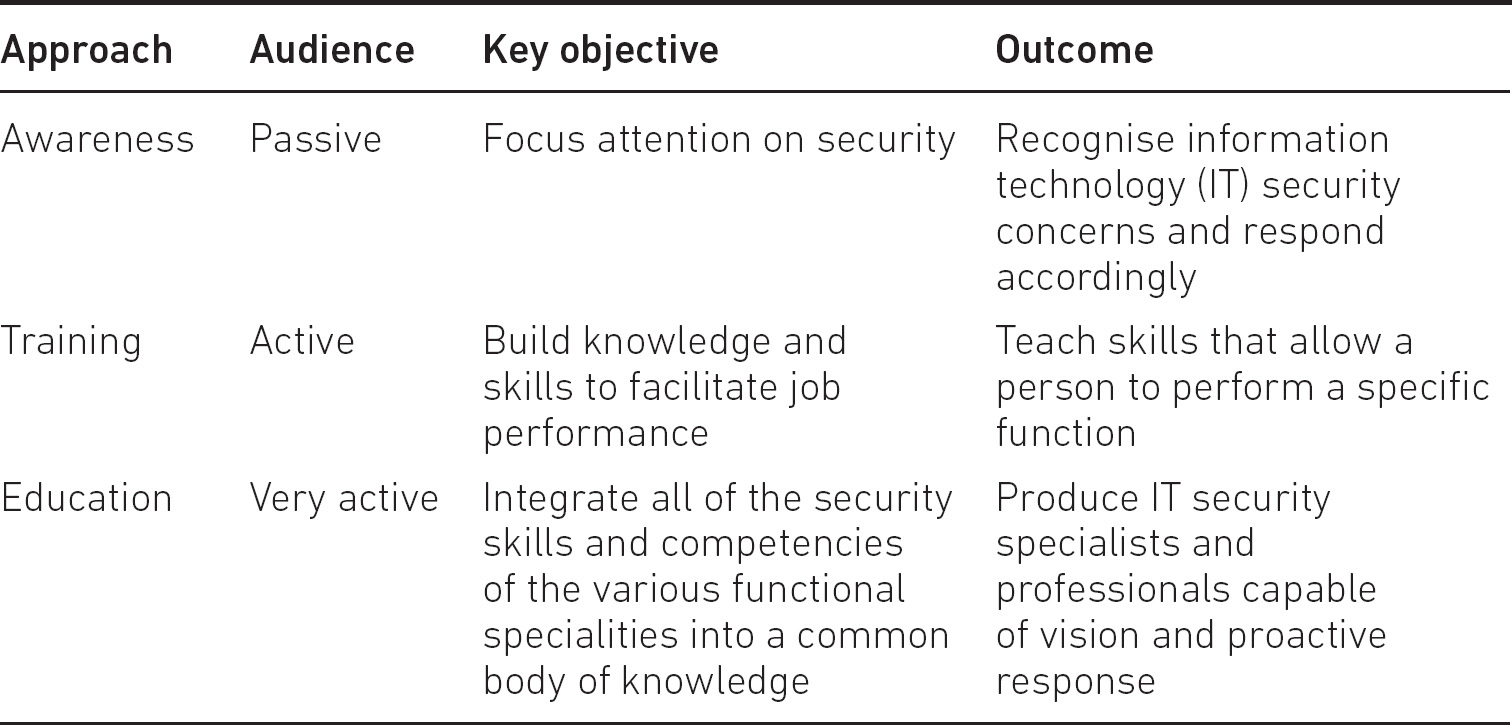

So, let’s start out by defining these three terms, using NIST SP800-16 and SP 800-50 as a basis.

Awareness

Security awareness efforts are designed to change behaviour or reinforce good security practices. Awareness is defined in US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication 800-1637 as follows:

Awareness is not training. The purpose of awareness presentations is simply to focus attention on security. Awareness presentations are intended to allow individuals to recognize IT security concerns and respond accordingly.

In awareness activities, the learner is the recipient of information [...] Awareness relies on reaching broad audiences with attractive packaging techniques.

Training

Training is defined in NIST Special Publication 800-16 as follows:

The ‘Training’ level of the learning continuum strives to produce relevant and needed security skills and competencies by practitioners of functional specialties.

The most significant difference between training and awareness is that training seeks to teach skills, which allow a person to perform a specific function, while awareness seeks to focus an individual’s attention on an issue or set of issues. The skills acquired during training are built upon the awareness foundation, in particular, upon the security basics and literacy material. A training curriculum may not necessarily lead to a formal degree from an institution of higher learning; however, a training course may contain much of the same material found in a course that a college or university includes in a certificate or degree programme.

Education

Education is defined in NIST Special Publication 800-16 as follows:

The ‘Education’ level integrates all of the security skills and competencies of the various functional specialties into a common body of knowledge, adds a multidisciplinary study of concepts, issues, and principles (technological and social), and strives to produce IT security specialists and professionals capable of vision and pro-active response.

Balancing awareness, training and education

Once you see the definitions in black and white, it is obvious that the three terms are very different and require different approaches for success. They also have different outcomes. However, the three are readily and easily confused – by vendors advertising awareness programmes that are training programmes based on their content for example – and by cybersecurity professionals.

Such confusion results in mixed messages, poor management of expectations and, eventually, poor outcomes. To help fix these terms in the readers’ mind and understand what each approach is capable of delivering, Table 1.1 is offered as guidance.

This table can help guide our thinking and provide a tool to integrate the various approaches. If we think about phishing campaigns for example, they are a mix of awareness – telling people that emails may be harmful and that emails are used for fraud, theft and so on – and a mix of training – getting people to click on ‘report phishing buttons’ or not to click on links. The clicking on the ‘report phishing button’ is a specific function that people are taught; nothing else. Getting the blend right between awareness and training is vital, as it equips people with the relevant knowledge, response and, where required, the specific action to take.

Table 1.1 Defining awareness, training and education

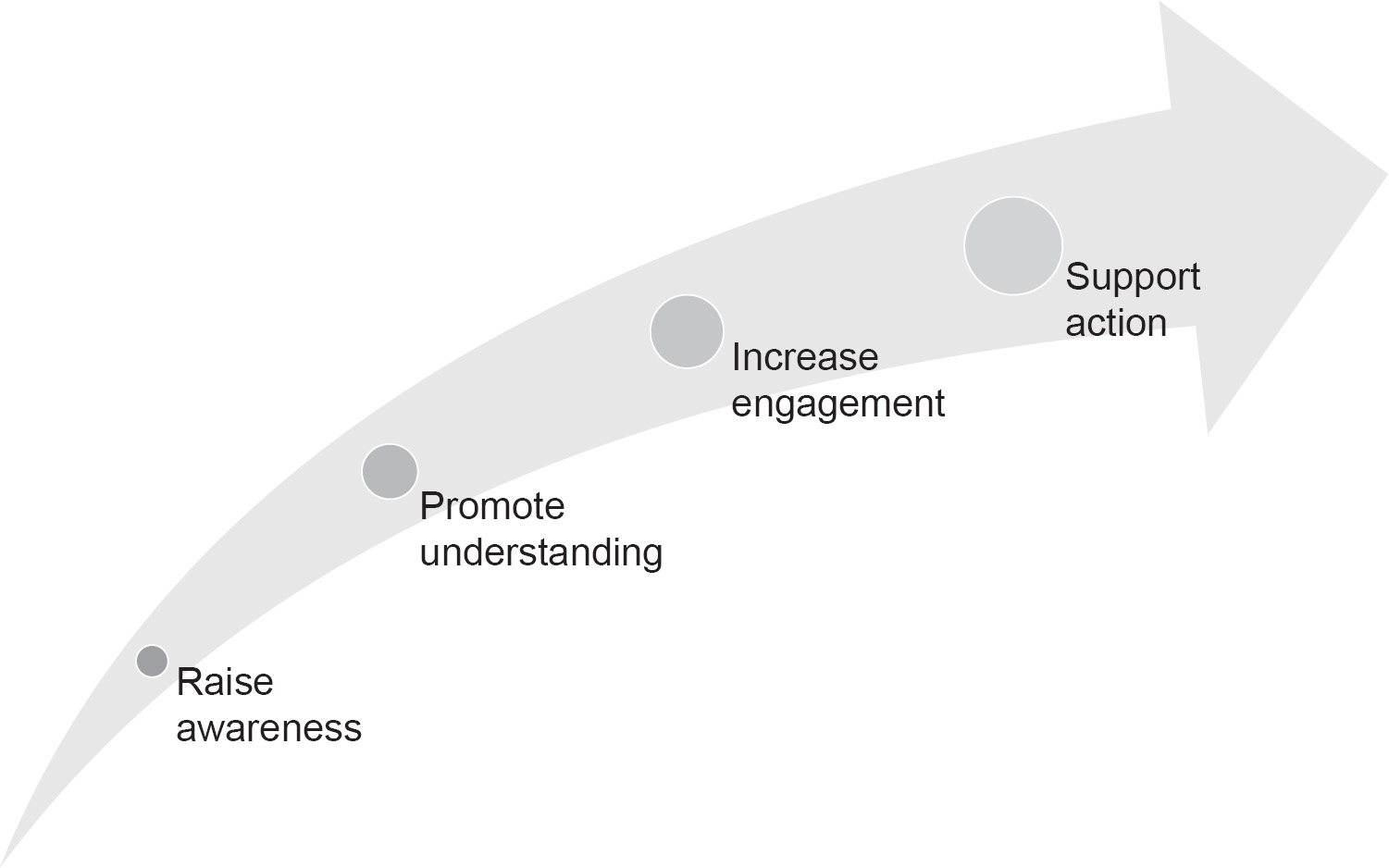

Awareness is often treated as a means to an end but for it to be most effective, it should form part of something bigger. Making people aware of an issue isn’t a call to action, nor does it tell them what to do, as described above. To make awareness work, it should lead on to further activities, as shown in the engagement journey, namely, promote understanding, increase engagement and support action, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 The engagement journey

Moving from raising awareness to supporting action will take time and will require the use of different skills and communication methods. If we look at the engagement journey, the start is the first step of raising awareness. That can be achieved by a simple conversation, a short video or even a message on a mouse mat. Raising awareness will typically be aimed at as large an audience as possible and will typically use ‘push’ or one-way forms of communication such as videos, lectures, online training and physical media. Next comes the harder step, that of promoting understanding. It’s easy to make someone aware of something but actually making them interested, willing to engage and spend time understanding what they are being told is harder. Typically, the audience size reduces as the effort required to promote understanding can be significant to reach a large audience. This step may involve regular presentations to groups by the security function, hands on demonstrations and follow-up. Once the audience reaches an understanding, then the programme needs to keep people engaged and interested. This is the point where the audience should be actively doing something, asking questions and even conducting simple tasks with supervision. Seminars, workshops and detailed briefings will be the tools of choice. Finally, the objective will be to get the audience to support cybersecurity actions and take an active part in making those actions happen.

Awareness, while covering the majority of people in an organisation, is one part of the equation. While it’s true that organisations will not seek to train or educate many individuals – nor could they within the typical budget provided – there is a place for identifying individuals or functions where the more in-depth approach of training or education could provide benefit. Education is often focused on particular individuals and on information security, for example through the application of professional certifications such as Certified Information Systems Security Professional (CISSP) and Certified Information Security Manager (CISM) or academic qualifications such as undergraduate and postgraduate degrees. This level of education can prepare individuals for promotions or allow them to gain further insight and raise their value to the security function and the organisation. Training can be extended to a wider group of individuals – a good example is training user access administrators to add user rights according to a security policy and procedure – thus ensuring that a consistent, secure approach is followed.

Ideally, taking into consideration all the constraints in an organisation, a balance between awareness, training and education should be struck. All cost time and money; all have particular benefits. Awareness is a ‘marathon, not a sprint’ and requires frequent repetition, is difficult to measure and yields the least obvious results, yet it is vital that individuals in an organisation have a basic comprehension of cybersecurity and the function. Training can be a one-off, can be measured (relatively) easily and can yield results quickly, while education may yield results over the longer term.

Building on our understanding of awareness, training and education, we can start to examine how we can deliver each of these to our audiences, which is covered next.

DELIVERY

When we think about how cybersecurity awareness is delivered, it’s often lumped in with IT or compliance subjects; through ‘merch’ (merchandise) – posters, cups, mouse mats and so on; often delivered as part of induction programmes (if such things exist); delivered as part of annual computer-based training (CBT) or via an ‘awareness programme’; on the intranet (as a microsite maybe, with downloads and videos); and included in newsletters. There is, of course, also the face-to-face delivery in a meeting, or over the phone when someone calls asking for help. Let’s briefly review the mechanisms of delivery and highlight some important features of each.

Annual training

The first delivery mechanism we touch on is the annual ritual of training and the incorporation of cybersecurity into that training round. In some industry verticals, staff have to undergo some form of annual training to carry on with their jobs. It is often seen as a good idea to bundle the annual mandatory training and topics such anti-money laundering, compliance and cybersecurity together. From one perspective, it means that everyone does the training (it’s mandatory), the completion of the training and any associated tests are recorded (so it can be proved that everyone has done the mandatory training) and it means that time doesn’t have to be found at other points during the year to run cybersecurity awareness workshops. From another perspective (that of the employee), it’s another course to get through as fast as possible in order to get back to the real work. Typically, little or no time is set aside to do these courses, nor is there any visible reward for completion. Even if there is a test at the end of the course, it’s a hurdle to get past, not a learning opportunity. Stories of interns completing training on behalf of staff members, or one person doing the course and then sharing the questions and answers with the team, which reduce the reach and impact of the training, are rife. Even if face-to-face training is used, it can be very hard to judge or accurately measure the impact, value or long-term benefit of that training.

Associated with this delivery mechanism is the awareness campaign, where a theme is chosen and then presentations, emails, articles and training are all bundled together and then distributed to staff over a period of time.

Merch

Traditional security awareness relies on ‘merch’, combined with some form of awareness programme, lecture or other training (e.g. CBT).

I remember seeing a poster in an office toilet38 in Norway (yes, really) that had an image of a toothbrush and the Norwegian equivalent of ‘you wouldn’t reuse this, so why reuse your password?’

There have been cups, coffee mugs, mouse mats and pencils, all with messages such as ‘Think security’, ‘Think, don’t click’ in organisational circulation and these are probably still doing the rounds in organisations today. Screensavers with such messages used to be popular as well. These are all passive methods of communicating – they all depend on an individual reading the slogans and then doing something – or being engaged enough to even take notice of the message. Unfortunately, employees can also become desensitised to these images and slogans, which further limit the impact and usefulness of merch.

New starter induction

Next comes new starter induction. Larger organisations can afford the luxury of a full day to orient staff but, even then, cybersecurity may be covered in only one or two slides. Typically, those slides won’t be delivered by a cybersecurity professional, so the messages need to be clear and succinct. The messages often get buried among all the other important things the new staff member has been told. And, of course, from day one the new staff member is starting to learn the culture. While large organisations can induct their staff, smaller organisations often can’t, so the new staff member learns on the job. Typically, the new staff member will learn from their peers and colleagues, so they will be further indoctrinated into the prevailing culture. In fact, it’s hard to escape the reality that most training really does happen on the job, day to day; and much of the learning happens by a process of observation. Some organisations have gone so far as to deliberately state that staff will learn by ‘80 per cent experience, 20 per cent training’.

Computer-based training

CBT ranges from the genuinely impressive to downright awful. Videos, stills and voiceovers all have their uses but they have to be done in the same style and with the same high quality. There is nothing worse than a mix of high- and low-quality images, bad voiceovers or inconsistent styles: all detract from the messages the CBT is trying to deliver. An effective CBT can attempt to tell a story, preferably one to which staff can relate, that highlights key decision points and the impact of the decisions taken. These decisions can then be referred back to what should have been done, the questions that should have been asked and the behaviour or policies that should have been followed. However, not all CBT follows this approach and is often slide-based regurgitations of policy statements, snippets from standards and quotes from laws or regulation, followed by a test. Hardly stirring stuff.

There has been an industry-wide trend to use phishing campaigns to train and educate users as a form of CBT to raise awareness. The majority of CBT tools for this are sophisticated, allowing multiple campaigns to be run, identification of repeat ‘offenders’ and even instant feedback should an end user click through the link. Without wishing to play down the impact of phishing, business email compromise and its variants, the issue here is that we can either desensitise the end users so they stop listening or, worse, they think that this is the only threat they have to be aware of – and so create other areas of weakness to be exploited.

Awareness programmes may not suffer from the same limitations as a CBT or online course. A good instructor and compelling slides, backed with real-world stories, can be impactful and draw the audience in. Unfortunately, the time and cost of preparing such a programme, allied to the time and cost of actually getting it in front of the business, militate against such programmes being run frequently if at all.

Use of intranet or a security website

Another frequently used delivery method is the intranet and the ‘security website’. The idea behind these is quite simple – a place where anyone can find what they need to know about security. The website can contain policies, CBT, presentations and can act as another awareness tool. Like any website, the security website needs frequent attention to keep it up to date, fresh and interesting. The maintenance of such a website takes time; writing or finding articles and content takes further time and effort. Unfortunately, the time needed for website maintenance can be gradually taken away by more important tasks, so the website loses its freshness and starts to become out of date. There is then of course a vicious cycle; it requires too much effort to update the website; no one visits the website, so why spend the effort on updating it; and so on. The website suffers from the same problem as ‘merch’; it is passive and relies on people actively visiting it and looking for what they want.

Newsletters

Finally, there is the newsletter or weekly update email approach. Still used by many organisations, the corporate newsletter would seem to be an ideal vehicle for keeping security in people’s minds. Similar to the website, effort is required to write the articles and hit the deadlines for publication. It is often difficult to know if the newsletter and individual articles are being read and to then measure the impact of any articles therein. Articles are much more effective when tied into other work – such as a phishing campaign – so each is reinforcing the other and readers get a sense of the wider picture. In some cases, different functions, regions or other corporate entities may produce their own newsletter – with perhaps a resulting negative impact on the overall readership of any of the newsletters received.

The mechanism or mechanisms by which we deliver our messages will impact the effectiveness of our campaigns. Different generations have learned to consume information in different ways and from different media, so we should look to use a blend of approaches to get our message across to the various audiences in an organisation. Using the same old approaches, for example email and print, may result in a percentage of our audience simply not seeing them – especially if our audience is on Slack (or similar) and Teams (or similar).

Now, this does not mean we should rush and create videos and images that would grace a TikTok, Instagram or YouTube account. Instead, think about how these and other media are used to get messages across to a wide audience. Clear messaging, supported by relevant visuals, in a time limited format lies at the heart of these approaches and result in an impactful and easy to understand package.

Despite the many routes we use to put our messages across, it can seem that nothing works; so, perhaps, it’s not us, it’s them?

PROBLEM EXISTS BETWEEN CHAIR AND KEYBOARD

We’ve all heard this or similar phrases about non-IT people; we may have used them ourselves. This simple phrase and accompanying attitude also sum up one of our biggest problems: we don’t ‘get’ the very people to whom we are trying to communicate. You can argue that this phrase (and its kin) reflects our own culture, in that we believe outsiders to be either uninterested, unintelligent or unable to do the (simple) things we tell them.

Now, before I get accused of painting employees as being completely unconcerned about information security, let me add this very large caveat: most employees try their best every day. They try to remember the right way of doing things, follow the processes and procedures and do all the other things expected of them at work. Cybersecurity is just one more thing they have to remember and do.

Let’s take a step back and think about our non-IT, non-cybersecurity colleagues. Typically, they’re employed to do a job in which IT plays a subordinate and supporting role. They’re expected to know how to use IT at some level; and the expectation is they know how to use email, word processing, spreadsheet and presentation software. Little or no training will be given when they join the organisation and it is likely that any training funds they receive will go towards their professional development. We talk of people and staff becoming computer and technology literate, but that isn’t necessarily true; they are much better at using technology, because it has been simplified – think of app stores, automatic updates and so on. Again, I am not doing down our non-IT colleagues; rather I am challenging our assumptions about what they really know when it comes to IT and what we really expect of them. If, for example, a user is used to going to an app store, downloading the app they want with minimal effort and then using it, then can we really expect them to know how to change the configuration or profile in a business app?

We should reflect on the messages we send as well; all too often we exhort people ‘not to click on links or attachments’ or ‘don’t click on links or attachments you don’t trust’ in emails but then we send people emails with links in – and ask them to click on them! Put yourselves in the shoes of someone who receives these messages; first, it’s incredibly confusing as I am being told one thing and then asked to do another. Second, I’m being told to make judgement calls in the work environment that I may not have the context, decision framework or understanding to make. In some cases, telling people to do certain things such as ‘hover over the link’ and see what the Uniform Resource Locator (URL) is can be worse than no advice at all – how does a non-specialist know the URL is a compromise tool? Finally, I am being told it’s OK to click on certain links or attachments as they come from someone in the organisation with a particular role; but I don’t know that person, nor do I understand where they fit in with my role or my sphere of interest. Without delving too much into the mechanics of trust, why should anyone trust you as the cybersecurity person? Why should they follow your advice when you seem to be contradicting it? As a result, what we think is a clear and unambiguous message is in fact the opposite and, if anything, sows doubt about us, our knowledge and why we should be believed.

We could argue that the problem does exist between chair and keyboard; but perhaps it is our chair and keyboard, not those of the non-IT specialist. In any business, like-minded individuals group together and develop their own culture, and their own assumptions and language. These groups can become closed shops, where the group opinions are perceived as being truth, not just opinion, and then start to be reflected back within the group, gaining veracity with each repetition.39 The peril of groupthink40 can also occur, so that decisions are made using the same terms of reference and with a desire not to destroy or upset the group. As a result, we believe what we (and our group) believe, and we believe that what we communicate to everyone outside the group is rational, clear and understandable because our group agree that is the case.

FOCUSING ON OURSELVES ALONE

Cybersecurity is not necessarily the best-loved part of an organisation, nor the best-financed. As a result, the team, function or individuals can become very closed and adopt an ‘us against the world’ mentality. It’s not unusual: many other functions in a business do it as well.

Unfortunately, this can mean that cybersecurity professionals stop looking for new ideas and for help in performing tasks outside the normal range of activities. When thinking about awareness, training and education, we’ll probably find that a significant percentage of cybersecurity professionals have never received formal training in how to create, populate and run cybersecurity programmes, how to measure their impact or how to measure the quality of the content. For example, security awareness occupies two pages in the CISSP Official Study Guide (Stewart et al., 2015) and these pages are concerned more with the setting up and management of the programmes, than the actual delivery. It’s probably also true that very few cybersecurity professionals have been exposed to pedagogical thinking, the theories about learning styles and marketing and communication methods. Again, this is not to downplay the knowledge and skills of the cybersecurity professional, but the items mentioned in the previous sentence are usually outside the knowledge required of such a professional, and the demands of the role do not allow time for learning this knowledge.

As a result, when designing or looking at awareness campaigns, the same ‘tried and tested’ methods are adopted; new ideas are either not known about or not applied as there isn’t time to learn, test and then apply them. This problem isn’t new; for example, Thomson and von Solms published a paper in 1998 in which they stated:

Techniques borrowed from the field of social psychology, which have been largely ignored in current awareness programs, are highlighted in order to show how they could be utilized to improve the effectiveness of the awareness program.

Much research, both academic and business, has focused on how to integrate non-security thinking, techniques and approaches with awareness. For example, using marketing techniques and treating non-security staff as customers has frequently been discussed; attempts to use gamification schemes described; and tactics such as influencing and drip-feeding information to arouse and maintain interest. However, much of this hasn’t yet borne fruit in organisations, mainly because of inertia, time and cost pressures and the ‘ourselves alone’ mentality described at the beginning of this section.

Overcoming this issue of ‘ourselves alone’ is hard. One of the most pertinent and interesting insights about security awareness is given by the Information Security Forum (2020) in their Standard of Good Practice. Paraphrasing somewhat, the relevant section states inter alia,

… cybersecurity awareness programmes designed and delivered by dedicated, specialist learning and development professionals and other subject matter experts (such as internal communications and marketing) (emphasis added).

That widely accepted statements of good practice still need to explicitly tell us to work with other people highlights how rare such cross-disciplinary efforts are, even in 2020. It is a truism that good people seek out people who can complement them; if you are strong in finance but weak in marketing, you work with someone with the reverse skill mix. We should do the same and actively seek out other experts’ opinions, advice and help – ‘ourselves together’ if you like – to seek new ways of telling our stories and new tools to communicate our message.

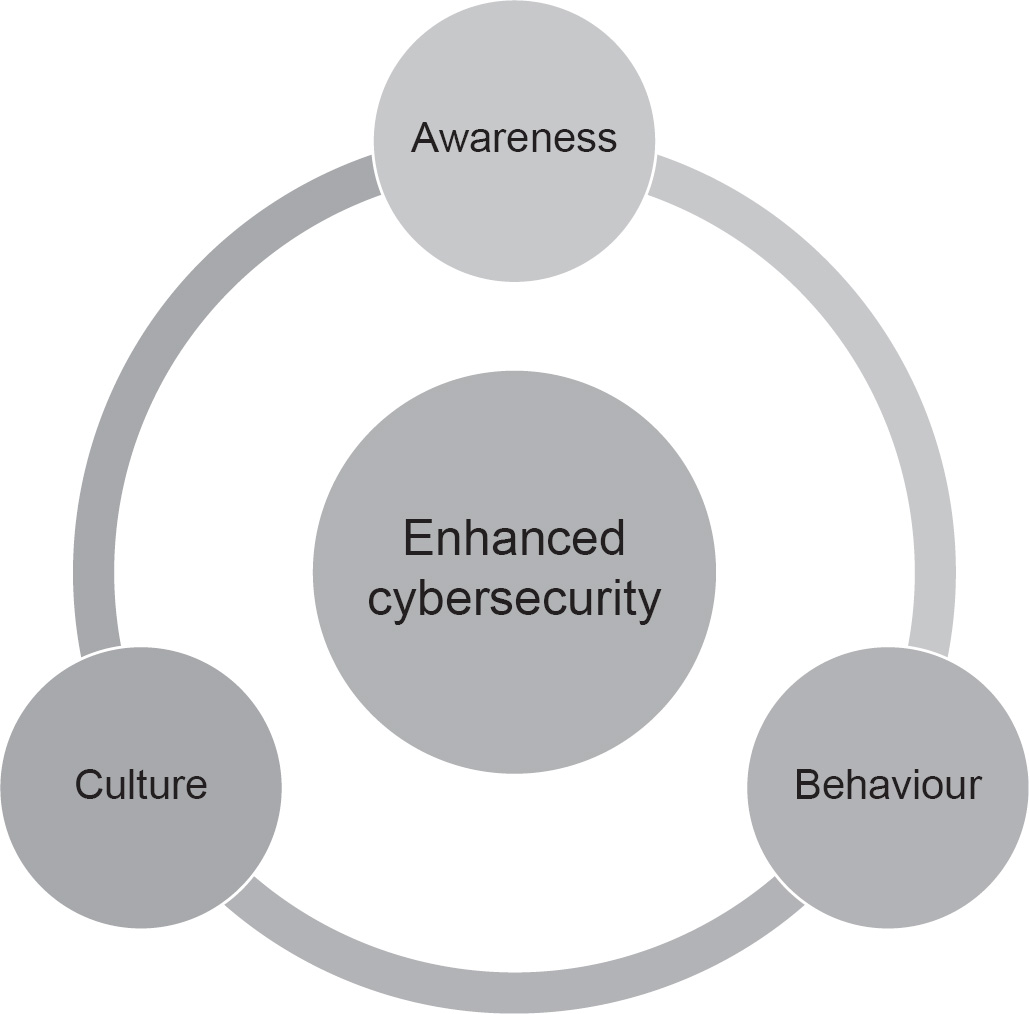

AWARENESS, BEHAVIOUR AND CULTURE

All the authors of this book agree that ‘the objectives of a cybersecurity awareness campaign should always be to change behaviour for the better and to strengthen cybersecurity culture’.41

For us, awareness is not the be all and end all. It is in fact one of three factors that can be used in combination to improve cybersecurity in an organisation. It is often a stated desire that we, as cybersecurity professionals, want to change the culture and create a ‘security culture’ in our organisations. Awareness is not enough on its own and we need to harness other tools and techniques to transform awareness into a tool to change behaviour and strengthen culture.

Behaviour change is not easy – ask anyone who has tried to stop smoking or keep to a diet or exercise regime – but there is a wealth of published material and expertise covering this topic. One of the more popular approaches was ‘Nudge Theory’, as put forward in Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness (Thaler and Sunstein, 2009). Simply put, a nudge makes it more likely that an individual will make a particular choice, or behave in a particular way, by altering the environment so that automatic cognitive processes are triggered to favour the desired outcome. Examples include placing fruit at eye level (or by the tills) in shops and chocolate lower down;42 making green energy deals the default; and placing hand sanitiser dispensers in easy to reach places in hospital wards to encourage hand hygiene for visitors and staff.43

We deliberately set our vision wider than the individual and their struggle to change behaviour. It is well known that a host of factors influence behavioural change. In the organisational context, which is what we are most interested in, one of the key factors is organisational culture. We’ll discuss what this term really means later in the book, but for the moment we’ll adopt the simple definition of ‘the ways we do things round here’. Importantly, we need to align our expected security behaviours with the normal behaviours expected and set by the organisational culture. Simply telling people to do something that goes against the culture is doomed to failure. Instead, awareness and behaviour must work within and with the culture to accomplish lasting change and improvements in cybersecurity.

This book, based on our experience, makes the explicit link that awareness is there to change behaviour. We can make people aware that it is better to eat fruit than chocolate (or other junk food) – but if we change something that helps people to turn awareness into (easy) action, then awareness is turned into concrete actions or thought. For us as security professionals, behaviour is a key part of our defences. Think of all the times we exhort people ‘not to click on links’, ‘don’t open emails from people you don’t know’ or ‘don’t leave your computer unlocked’; in fact, all of these are learned behaviours. We are (subconsciously) asking people to change behaviour but not following it up with the insights needed to make that behaviour change or stick.

We will look further into behaviour and behaviour change in this book and how we can use well-known techniques to encourage simple actions that make a big difference to our security. Behaviour change is not an overnight phenomenon and there can be many setbacks and false starts. However, as we discuss, using the twin tools of awareness and behaviour change can increase the probability that change will happen and, most importantly, become the new norm (or the change will ‘stick’).

Recalling our previous discussion, we identified six factors that can make up a culture. I’d like to draw your attention to three components of the cultural web: stories and myths, rituals and routines, and control systems. Stories are an incredibly powerful way of transmitting shared or expected values and behaviours and what happens to those who adopt or reject those values or behaviours. Rituals and routines also create and impress expected values and behaviours on new and existing staff. Control systems also impress and reward expected behaviour, making behaviour even more significant. If people are rewarded (in whatever way) for following expected behaviour, then they will copy the expected behaviour.

We can quickly see that culture has a significant behavioural component. Change the behaviours, change the stories, rituals and rewards and you can change the culture. We talk of creating or maintaining a ‘security culture’ in our organisation and how awareness can help us in that task. With such a dependence on behaviour, we can quickly see that awareness on its own will have little impact. We thus go back to the comment at the beginning of this section, ‘change behaviour for the better and strengthen cybersecurity culture’. One of our levers to change culture is behaviour.

In a manner similar to behaviour change, culture change is not an overnight phenomenon. We can address the creation and maintenance of a ‘security culture’ through small, meaningful behaviour changes. Trying to change a culture through a single massive intervention is risky – and just because chief executive officers (CEOs) have managed it in the past, doesn’t mean it is a blueprint for the future.44 It is often easier to change culture through small, well-defined changes and use these as stepping stones or employ their combined effect to make the required changes. Importantly, to change culture, we need to understand and define what the culture already is – a task we will examine later in the book.

So, to finish this introduction, let me provide you with a simple model of the ABCs (Figure 1.2).

From this diagram, I hope you can see that the three components of the model are (intimately) linked and that a change in one will affect the others for good or bad. The ‘ABC wheel’ also exhorts you to think how to use the components to best effect, so if you want to change behaviour, you examine how both awareness and culture can positively contribute.

SUMMARY

Cybersecurity awareness is important. Organisations are becoming ever more reliant on technology and data and this reliance is set to increase, as more and more data is generated by people and machines. As this reliance and dependence increases, so the effects of an incident also rise – not just in terms of time lost in managing the incident but in terms of regulatory and legal fines, brand and reputation damage, and external scrutiny. The cost of an awareness programme is certainly less than the cost of a breach.

Figure 1.2 Simple cybersecurity ABC model

However, despite its importance, getting security awareness to work is a perennial issue. This chapter has discussed some of the reasons behind why we struggle to make awareness work. We believe that awareness can only work if it is part of something larger and used in conjunction with the tools and techniques to change behaviour and strengthen culture from a security perspective. The next chapters will examine the ABCs – awareness, behaviour and culture – in much more detail and provide a new approach to delivering the lasting change and culture for which we all strive.