The rationale for a data strategy has been established in the previous chapter. The challenge now is how to position it within the organisation. The data strategy may be new, or it may be reworking a previous data strategy that promised a lot and achieved little, other than filling shelf space and gathering dust. Either way, the organisation is probably not yelling out for a data strategy. So how do you establish a need, build a level of interest, and then deliver something which will resonate with the wider organisation and therefore stand a fighting chance of transitioning from theory into practice?

This chapter will be based on a simple question, which then triggers a series of supplementary questions: why do you believe you need a data strategy? Is this something you have initiated – in which case, why? And, if so, how have you pitched it to others? Are they engaged? Do they understand what they will get? Or have they simply nodded their approval on the basis it won’t impact them and it is perceived as a way to keep you engaged in anything other than interfering in their business?

If the data strategy has been commissioned by the executive board, what has triggered this and why now? Is there something topical, whether positive or negative, that has suddenly made the executives realise the need? What is their expectation of what is required and what impact do they expect it to have?

Prior to commencing the work on the data strategy, it is essential to establish the right environment. This involves:

- preparing your stakeholders with some appreciation of what is to come;

- being clear with stakeholders what you need from them to support you through data strategy definition and execution;

- being clear on the transformation it will drive as a result.

Anything less and you might as well start to clear shelf space for the latest edition of the data strategy to accompany its predecessors.

The fact that a data strategy has been commissioned does not necessarily reflect the organisational maturity to embrace having one. The work above goes some way to preparing the ground on this, but you should also steel yourself for a detached reality – the executive board gets it, wants it and has asked you to lead on defining it, but the rest of the organisation is not on the same page. In many cases, you will find a data strategy that flounders not from the lack of executive commitment, but because of the inability to get traction where it really matters, beyond the executive board and into the minds of managers and employees in your organisation. It may be a lack of communication, resistance to change or a number of other reasons, but your task will be to cut through this if you are to succeed.

This topic will be discussed at some length in this book, but bear in mind that there is a difference between executive buy-in and the need to mobilise the whole workforce if your data strategy is to have any likelihood of success.

What do I mean by data strategy?

I have found that the corporate lexicon has appropriated terms in the wider data and information arena that have become increasingly unhelpful. Take chief information officer (CIO) as an example. This was borne out of the widespread use of the term ‘information technology’, yet, perversely, the technology bit was dropped and information stuck, despite most CIOs having historically had little focus on information (in terms of the generation of it from data) or being the right person to lead on information across the organisation.

In the same vein, data strategy is often a misnomer for a much wider scope of coverage, but the lack of coherence in how we use the language has led to data strategy being perceived to cover data management activities all the way through to exploitation of data in the broadest sense. The occasional use of information strategy, intelligence strategy or even data exploitation strategy may differentiate, but the lack of a common definition on what we mean tends to lead to data strategy being used as a catch-all for the more widespread coverage such a document would typically include. Much of this is due to the generic use of the term ‘data’ to cover everything from its capture, management, governance through to reporting, analytics and insight.

2.1 TERMINOLOGY – SO WHAT IS A DATA STRATEGY?

For the purposes of this book, the term ‘data strategy’ is used in its widest sense, rather than confined to purely data collection, storage, governance and compliance – its management, if you like. It also encompasses its exploitation, which can take many forms, as data is there to help the organisation make effective decisions and deliver effective outcomes for its customers and its workforce. However, there is not universal acceptance of or agreement on the application of the term, and so you may find that there are subtle differences in what one organisation would expect in a data strategy to the next.

Depending on your organisation, you may feel the term ‘data strategy’ is limiting, constraining it to data in the narrowest sense and therefore perceive it to be an unsatisfactory term for something that covers a wider spectrum. From a purist point of view, the term ‘data strategy’ would seem to limit, but in reality data is a commonly used term that is often describing not only the data itself, but also its exploitation. I tend to suggest you go with the flow within the organisation, and if data is a term commonly used more widely then stick with it. You can define it up front, but it is far more important to have a term which stakeholders across the organisation are comfortable with, as they will provide the resources and support to turn delivery into success.

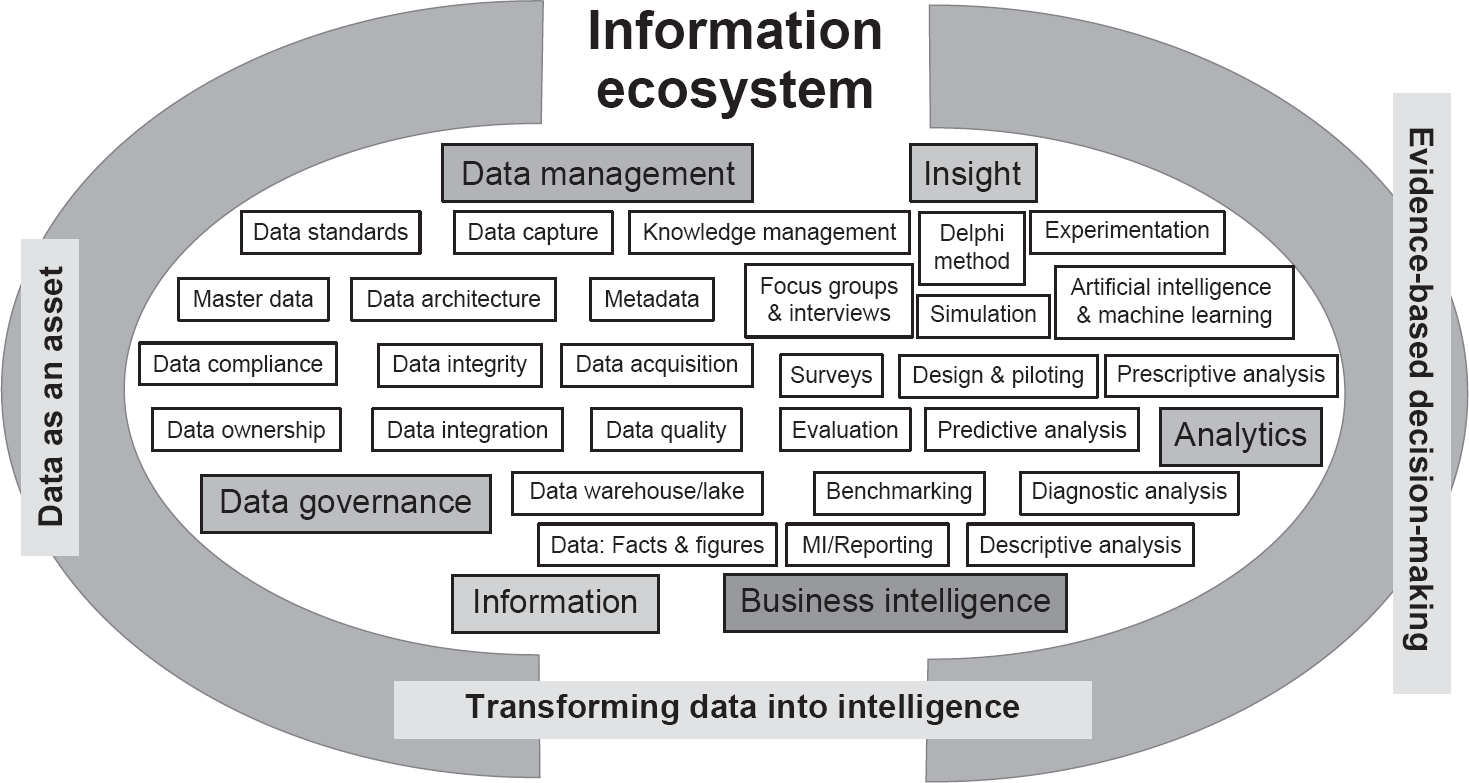

I am using ‘data strategy’ as an overarching term to describe a far broader set of capabilities from which sub-strategies can be developed to focus on particular facets of the strategy, such as management information (MI) and reporting; analytics, machine learning and AI; insight; and, of course, data management. The breadth of the definition of a data strategy being used in the context of this book encompasses all parts in the information ecosystem in Figure 2.1. In my opinion, the full range of end-to-end activity involving the transition from data collection to its exploitation and, ultimately, archiving and deletion in line with compliance is essential to regard as one integrated operating model and is therefore best coordinated as a single strategy. In terms of your own approach, as long as it is made absolutely clear at the start of the data strategy document as to the definition you are applying then any ambiguity is avoided, and the relevance of the scope of the definition is more an academic point than an obstacle to the value of the data strategy itself.

I would argue that the first hurdle is successfully negotiated if the organisation has identified it has a need for a data strategy; the precise meaning and therefore the content can be agreed as the expectation is explored with the executives who have commissioned it.

Figure 2.1 The information ecosystem

Figure 2.1 demonstrates the diversity of content in an information ecosystem. It starts with data management and governance setting the foundations to establish data and information as an asset, through to analytics and insight establishing the value from evidence-based decision making.

The data strategy should certainly cover the following from the ecosystem:

- Data management, as it is commonly termed, including structured and unstructured data, by which I mean:

- data standards;

- data architecture;

- data governance and quality;

- data integration and migration;

- data acquisition;

- data transformation and exchange (that is, with other parties, requiring typically a memorandum of understanding between both organisations);

- data compliance – including regulations and any other legal constraints – and corporate data security;

- data accessibility – providing appropriate access to the people who need it;

- master data management – which systems hold the primary version of data, and which leads in to the systems strategy, in terms of rationalising (potentially part of technology debt) or acquiring systems.

- Data exploitation, which can be subdivided into:

- reporting and the provision of MI, especially key performance indicators (KPIs), usually involving dashboards and other visualisation techniques;

- analytics (descriptive, diagnostic, predictive and prescriptive), including the application of machine learning and AI (sometimes referred to as data science);

- insight – the gathering of additional information and data through research activities to fill gaps in understanding or test out approaches, and the benchmarking and baselining of activities and performance to determine comparative performance with other organisations conducting similar activities;

- knowledge management to garner real insight from a myriad of internal sources that are often unstructured and difficult to capture and/or harmonise to deliver coherent insight for the organisation in a structured form.

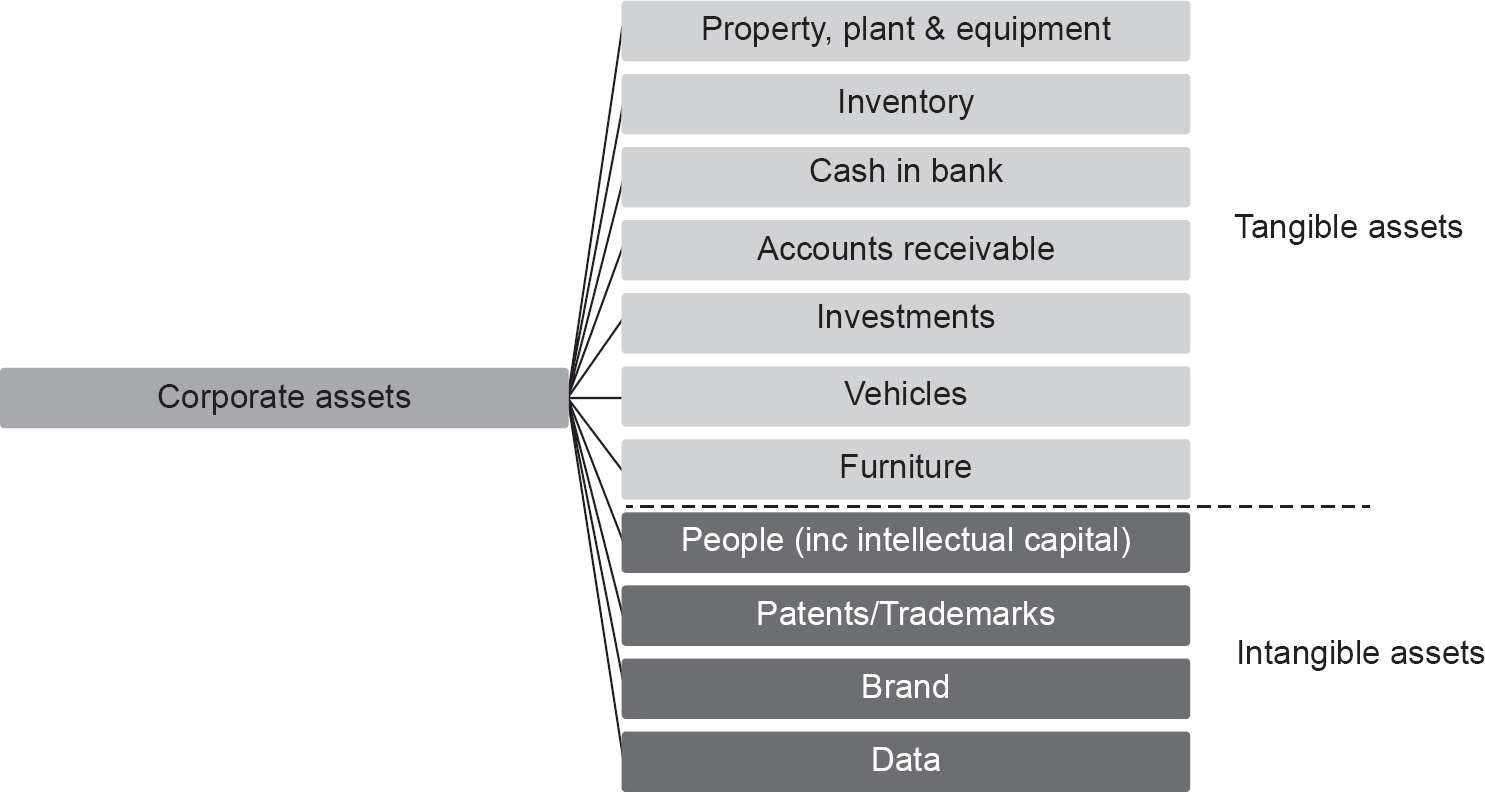

The data strategy will start the process of making people within your organisation recognise data as an asset (Figure 2.2). This may be happening for the first time – perhaps data has been overlooked and assumed to date, rather than managed as an asset class in its own right – or you may be in a position where there is a recognition of data and its importance to the organisation already. Either way, every organisation today is a data business of some sort, with a value attached to that data. If the organisation has not recognised this yet then it is a real opportunity to use the data strategy as the lever to make people realise that data is indeed an asset, it has value and this can diminish if it is not captured, managed, maintained and utilised correctly. If you can change the thinking of your organisation to reflect this, then you are truly on your way to reorientating your organisation to become a data business.

Figure 2.2 A perspective on the assets of an organisation

The accounting standards as to what constitutes an asset are very clear. The International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) definition states: ‘an asset is a resource controlled by the enterprise as a result of past events and from which future economic benefits are expected to flow to the enterprise’.2 Despite this being further classified into operating and non-operating assets, data is still not recognised, whilst people – the hearts, minds and resource that makes the organisation operational – are not considered other than through the conversion of their intellectual capital into specifics, such as patents, trademarks and the like.

Further, the IFRS state that an asset has three key properties: ownership, such that it can be turned into cash and cash equivalents; economic value, enabling it to be exchanged or sold; and resource, which can be used to generate future economic benefits. Clearly, data does not meet these directly, but with a little imagination it is feasible to argue that data can be sold, that it can certainly generate future economic benefits (otherwise many acquisitions would not hold water as viable transactions) and that an organisation ‘owns’ the data as an asset. Yet, despite this it is still not officially classed as an asset.

However, this shouldn’t stop you managing it as you would any other precious enterprise asset.

For example, in the bankruptcy evaluation of Caesars Entertainment Group – the owner of Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas – the most valuable asset was not the physical resort or the land, it was the customer loyalty programme which consisted of 45 million members and was valued at $1 billion by creditors.3

Increasingly, as some of the world’s biggest corporations do not come from traditional bricks and mortar institutions but are technology and data driven, the balance of assets will need to reflect the value of those assets which the financial regulators seem to struggle to incorporate into their strict definitions. In today’s crowded marketplace, you need to be able to compete on many fronts – price, product, service, brand, delivery – and differentiating your organisation based upon the intelligence that effective exploitation of data can bring is an important way to build your customer base into one which delivers repeat business and increases profitability. In reality, every organisation needs to be a data business in the 21st century, and this necessitates treating data as a precious asset. If you are aspiring to be, or are already, a data business then you are in need of a data strategy to harness it and drive your organisation forward.

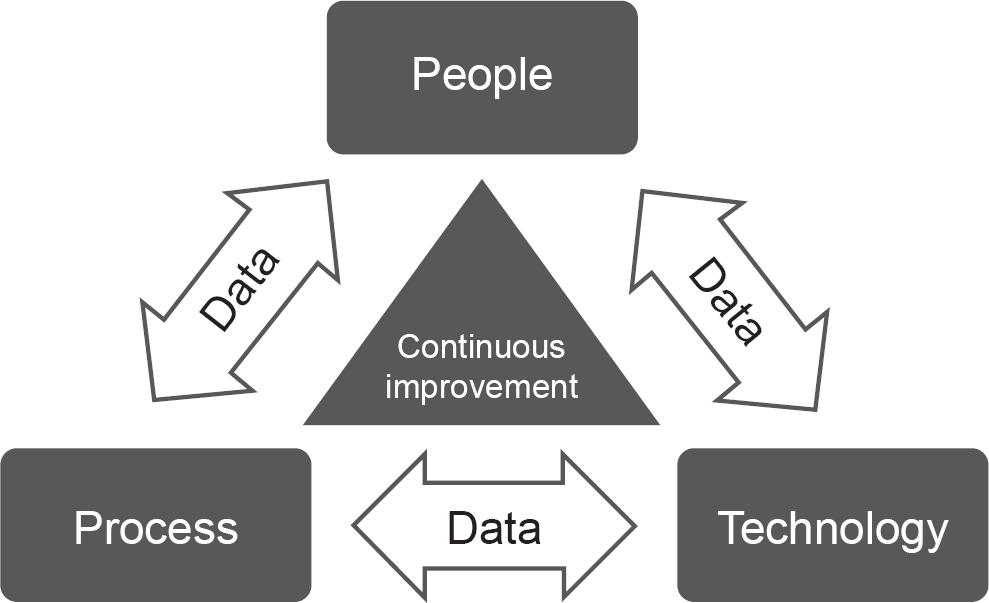

Do reflect that data strategy is pivotal to the activities of the organisation. It encompasses the trinity of people, process and technology, all of which are entirely data dependent as none of these operate without using data at their heart (Figure 2.3). Consider:

- what employees need to enable them to be empowered in decision making;

- how data enables a process to flow efficiently or otherwise, and how it can enable significant improvements through data capture, maintenance or enhancement;

- technology that works with the data, managing, presenting and manipulating it to enable the organisation to deliver its products and services to its customers in an optimised fashion.

Figure 2.3 The triumvirate of people, process and technology, enabled by data

It isn’t always practicable to deliver all three in a way that drives improvements across every one of these, and at times compromises have to be made, but it is useful in considering how the data strategy will make a positive impact, enabling the organisation to achieve its overall goals more efficiently and effectively.

2.1.1 Differentiating the data strategy

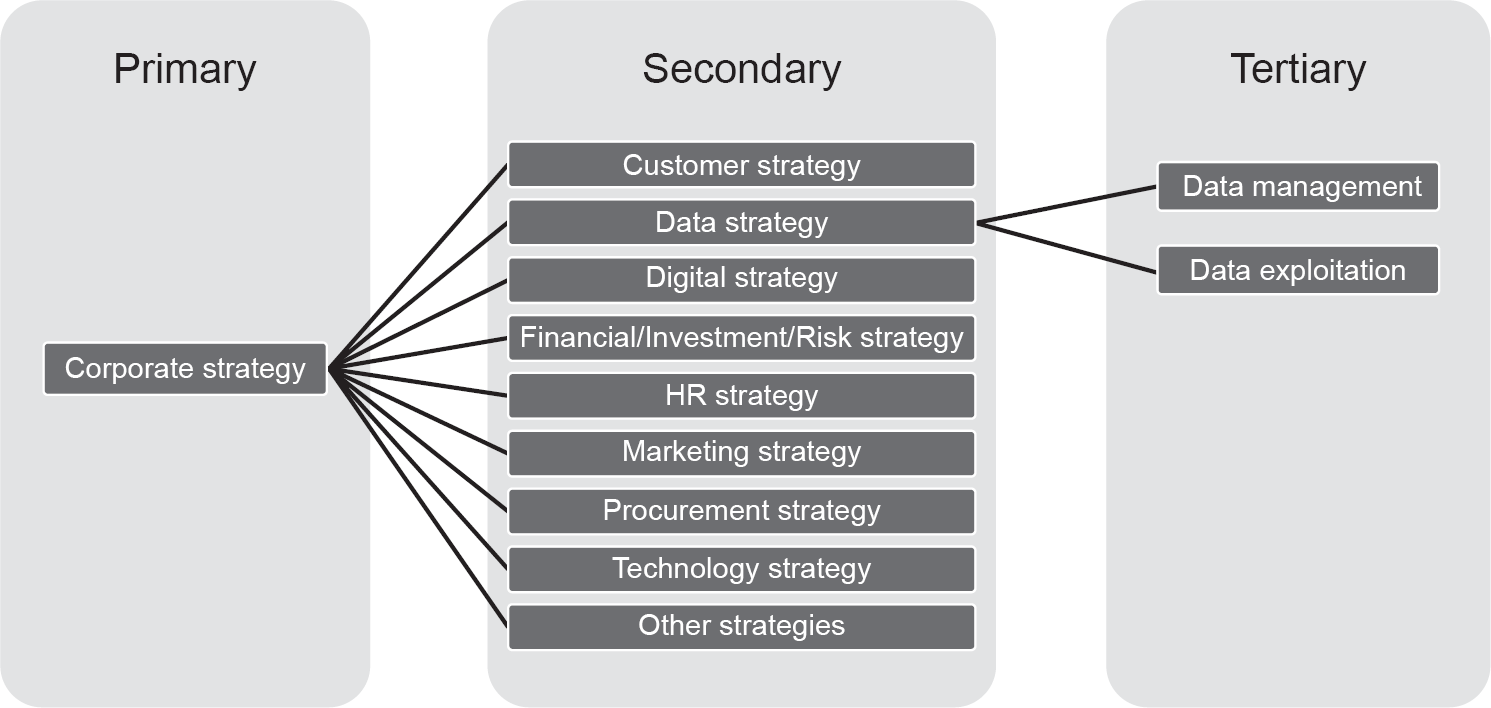

I would suggest that there is a difference between what I am loosely terming data strategy and other related strategies, such as a digital strategy, technology strategy or a compliance/risk strategy (I cover this in more detail in Chapter 6). The data strategy will feature in, and be dependent on, all of the above but will have this relationship with many other functional strategies within an organisation. This is key to ensure that the strategies all converge, and to recognise the dependencies between them and to keep them synchronised throughout to avoid divergence.

Each strategy within an organisation should be set out clearly in terms of its scope and remit, to ensure there is clarity as to how each of these dovetails with one another. Linkages should exist, recognising the interdependencies, and it should be easy for a reader of one strategy to forge links between separate strategies to connect these dependencies. The key to establish, within the definitions and scope, is the primacy of strategies on any particular topic. This will make it easier to track where dependencies sit and the key driver lies, otherwise it is difficult to keep the range of strategies synchronised. There should be a lead for each strategy within the organisation, and if there is any doubt about the scope of the data strategy, I would recommend engaging your counterparts on the other strategies to ensure there is clarity.

There could be a range of strategies within your organisation (see Figure 2.4), depending on the maturity and approach it takes. Typically, each functional area will have a strategy, and whilst there are some interdependencies at work, it is the cross-functional strategies such as data, digital and technology which are most likely to cut across the majority and therefore have these interdependencies. You will find, therefore, that the secondary strategies have relationships which the tertiary strategies may underpin with more detail.

In terms of the data strategy, it is most likely that this will enable a number of aspects of the other, secondary, strategies to be achieved as there will inevitably be a data angle, whether to aid new processes, decision making or the evidence and measurement to demonstrate a successful outcome.

2.2 THE RELEVANCE OF A DATA STRATEGY

The data strategy needs to provide a clear line of sight between the vision and purpose it is serving and how that fits in with the direction of the organisation and enables the delivery of the corporate strategy. It has to be relevant to all, and therefore accessible in its language and intent.

Figure 2.4 Multiple strategies enabling the corporate strategy to be delivered, with sub-strategies in support

In theory, every organisation should start with a data strategy aligned to the corporate goals before embarking on collecting and acquiring data. In practice, this is rarely possible and the fast pace of events in new start-ups tends to preclude the breadth of thinking that would be needed in a data strategy within a year or two. However, the concept of the data strategy serving the corporate goals, as defined in the corporate strategy, is certainly one which is essential for delivering successful outcomes for every organisation.

In today’s fast-moving world, data is growing exponentially – it is claimed that 90 per cent of the data available in the world today only became available in the last two years4 and 2.5 quintillion bytes of data are produced every day.5 By 2025, it is predicted that there will be 463 exabytes created daily globally.6

At one point, there was a view that data could be stored at low cost, which led to a mindset of ‘let’s keep it all’. However, the sheer scale of data at our fingertips in our organisations today and the growing overhead to keep acquiring and integrating it has made this more difficult to do in a meaningful way, and the regulatory frameworks have moved on to challenge the legitimate reasons for organisations retaining data if they cannot demonstrate a purpose related to its collection to do so. In addition, the regulations are seeking to move organisations to anonymise data if possible, to remove the risk of identification beyond a period in which that identification can be justified, and making data retention based on an opt-in model rather than the onus on the person to opt out.

The data strategy may be prepared and thus nominally ‘owned’ by a specific function. In many cases, what is seen as the natural home for data is actually quite the wrong one – the IT function. There is a common misconception that the people who run systems in the organisation must also be the right people to fix the data. The IT function does deliver systems into the organisation, but it is people in the rest of the organisation who are predominantly the users of these systems and create and manage the data that resides within them. The default to IT is a sign that the organisation has not recognised that this is a team game, that data is the lifeblood of the organisation, and hence it has to be a corporate-wide initiative to fix what is largely an operational problem.

In many senses, the lack of awareness of the wider responsibilities for data are the reason why many CIOs fail to really get to grips with the data management issues in hand. In a survey commissioned by Dun & Bradstreet,7 45 per cent of respondents said it was challenging that data was in the domain of the IT function rather than the business. Without the wider organisation falling into line, there will be no change in attitude or increase in responsibility.

Ownership needs to reside in the senior leaders of the organisation who are setting the goals of the organisation and dependent on having the data to achieve them. Data strategies driven by the IT function tend to focus more insularly on the things it can have some influence over, such as data storage, security and retention – which are admirable in their own right, but a shadow of what a real data strategy needs to contain to drive an organisation forward.

The growth of the chief data officer (CDO) role in larger organisations provides a natural home for the definition and preparation of the data strategy, although this role is not common across small and medium-sized enterprises. However, it does not need to be a CDO – I have rarely worked in an organisation with a CDO, perhaps because someone is doing the role of a CDO but without the title (for instance, I have been a CDO in all but name in several organisations). The key is to have the right level of executive buy-in, so someone at the executive board level would be ideal.

It is essential that the data strategy has widespread acknowledgement and buy-in throughout the organisation. To achieve this, it is imperative to have stakeholder engagement throughout the process of formulating the data strategy. As with good analytics practice, there is a need to adopt the principles of Agile (discussed later in the book) and be prepared to plan – do – check – adjust/act (PDCA), which provides a reality check as to whether the data strategy is supporting and enabling the wider organisation and thereby has a chance of being adopted. All too often, organisations do not engage when devising a data strategy, only putting it to the test when in a final draft stage, by which time a lot of time and effort has been expended and a negative response is seen to be a disaster. Get the feedback in early, co-create the data strategy and build a sense of momentum behind it within the organisation.

It is also important to regard the data strategy as a living document. Do not regard it as a masterpiece, never to be reviewed, amended or critiqued within the time frame it covers, but instead see it as a strategy that can flex to the changing demands of an organisation.

In one of my assignments, I was shown a data strategy that was no longer in use and regarded as obsolete. It turned out the organisation had acquired another company and so the focus of the organisation shifted to integrate the new business, and hence the data strategy was not fit for purpose any more. No one seemed to think of reshaping the data strategy to keep it relevant, and it seemed as if there was an acceptance to move from a data strategy to a series of tactical decisions devoid of any overarching strategic direction.

2.3 ALIGNMENT WITHIN THE ORGANISATION

As discussed earlier in this book, the term ‘strategy’ was slow to make it into the business lexicon but it now seems ubiquitous. Every area of the organisation seems to have a strategy, so where does the data strategy fit?

The key for a successful data strategy is to align it clearly with the corporate strategy. The data strategy is a crucial enabler of the corporate strategy, and the data strategy should clearly call out those components that have a clear line of sight to delivering, or enabling, the corporate goals. If the data strategy does not align to the corporate goals it will be a much more challenging task to get the wider organisation to buy into it, not least because it will fail to have any resonance with the objectives of the organisational leaders and be regarded as optional at best.

If the data strategy does not align with the corporate strategy it is because the author of the data strategy either has missed the clear links that will be there or has a completely different agenda to the rest of the organisation. The former is alarming, but the latter is likely to lead to a parting of the ways between employee and employer! It is important to stay grounded in the drivers of success for the organisation as a whole and to frame the data strategy in that context.

Of course, this presumes all the relevant strategies are in place, which may not be the case. It may be that there are operational plans being followed which are one-year proxies for a strategy, which is far from ideal but will need to be considered in the context of devising your data strategy. It may also be that other parts of the organisation are working on their strategies too, but are running behind yours. If this is the case it warrants additional effort to try to remain synchronised in the thinking and the management of dependencies and assumptions, but there is always the potential to diverge. There is also the possibility that the other strategies are simply not well written, lacking sufficient clarity in that they are ambiguous or misaligned in their own thinking and as a result fail to support the corporate strategy goals.

I can only advise you to be bold – highlight the potential flaws in those strategies as you see them impacting on your data strategy and be prepared to help in any redrafting of those other strategies to ultimately lead to better alignment with your own.

Should the data strategy slavishly follow the corporate strategy? Despite my comments above, the answer is no. There should be a symbiotic relationship between the data and corporate strategies, otherwise the opportunities to do things differently that lead to better outcomes – and to be innovative in how the analytics and insight outputs are utilised, which in turn can lead to opportunities that might otherwise not be spotted – will not arise. Therefore, the data strategy has to be developed against the framework of the corporate strategy first and foremost, but not be constrained by it in its ambition to go beyond.

A challenge I set when devising a data strategy is to ask what value-add will it bring to move the organisation forward, and how recognisable will the difference be should the full scope of the data strategy be delivered. I believe that those responsible for devising the data strategy have to take the same level of accountability for realising the benefits within the data strategy as an executive board does with the corporate strategy. This also makes the task of translating it into practice a more ‘real’ activity, as the data strategy has to be capable of being implemented – both in terms of the clarity within the data strategy but also with regard to the feasibility.

This is all the more challenging if you are operating in an organisation that is perhaps limited in its adoption of the latest technology through either a conservative approach or a lack of budget to invest. Similarly, in an organisation that might be termed as ‘data naive’ it can be difficult to get traction, or at least to do so in the right places to make progress that can be embedded into the organisation. In both cases, strong leadership in data strategy can make a real difference to such organisations, but it needs absolute commitment from the executive board to get behind your strategy implementation. The board will need to recognise that some of the key deliverables will not reap immediate benefits or generate revenue, but are essential enablers and hence require prioritisation and investment.

If the data strategy is a key enabler of the corporate strategy, then it is important that those deliverables within the data strategy are clearly articulated and linked directly to the success of the organisation. It surprises me how often this gets overlooked when the data strategy is being devised, yet it is a compelling business case in itself to demonstrate the dependency for the wider organisation to be successful, and to ensure that the data, analytics and insight areas are at the heart of planning for those activities to be resourced and the right approach is defined.

The alignment with the corporate strategy is best achieved if, amongst the stakeholder group that is engaged from the outset, there is representation from the corporate strategy area. This raises the profile of the data strategy within the organisation, identifies the dependencies and enablers linking the data and corporate strategies, and enhances the credibility of the data strategy. This is especially important if you are developing the data strategy in your organisation for the first time – you want every opportunity to raise the profile of the work you are doing to ensure it has every chance of becoming embedded into the organisation.

2.4 A SUCCESSFUL DATA STRATEGY – MAKING IT CLEAR!

The case for a data strategy has been made, so what are the essentials to make it a success?

I recommend focusing on five key attributes that underpin the data strategy process and which you will likely want to refer to throughout the process of defining and developing the data strategy. They form the acronym ‘CLEAR’, which in itself is a useful reminder of what you are seeking to achieve in developing your data strategy.

2.4.1 Clarity

It is important to bear in mind the need for clarity throughout the process of developing a data strategy. This operates on many levels, as I shall explain, but it is an overarching discipline to follow from the very outset of this process.

The start of the data strategy definition process requires absolute clarity. It needs to align with the expectation you have created within the organisation as to what the data strategy will encapsulate, the impact you have outlined it will have on the wider organisation and the positioning of the data strategy within the organisation. It is essential to have commitment across the organisation to support and embrace the approach to developing the data strategy and to be clear on the demands you are placing on the organisation to peer review and comment as the data strategy takes shape.

The data strategy itself needs clarity in its communication, and this is where stakeholder engagement needs to be deliberately involved to provide active participation and reviewing of the document as it is developed. Part of this is also to ensure the data strategy is written in plain English (or whatever language it will be produced in), avoiding technical terms, ambiguity and acronyms and, most of all, keeping it simple. You may wish to consider the lexicon of terms used in relation to that recognised within your organisation, as it makes sense to write the strategy in a way which chimes with what your stakeholders would recognise and relate to.

It is important to remember that to engage senior stakeholders and staff outside the function largely responsible for delivering the data strategy, there is a need to keep the content short and clear; the document should not be an onerous read and should be focused on what the strategy aims to achieve rather than providing detail of how it will be delivered.

The use of terms which may seem commonplace to the author of a data strategy may not be clear to the reader. It will prove a major obstacle to the data strategy if the reader is unable to understand, simply because terminology has created a barrier. Therefore, it is essential that jargon is kept to a minimum: where it is felt that it is needed, the terms should be explained fully, with an annexe providing a list of all such terms used throughout the document.

2.4.2 Leadership

The data strategy is setting the stall out as to how the organisation’s capability in the important area of data, analytics and insight will deliver change to the organisation over the period it covers. It must provide clarity, but, more to the point, it has to give leadership and direction.

The key to achieving this is to engage stakeholders from the outset. It may seem unusual to get those who may be outside the relevant areas of expertise involved so early, but it is about setting the context and thereby demonstrating that the data strategy is pivotal to achieve the corporate goals. Early engagement of stakeholders provides the opportunity to seek feedback, including how easy it is to digest and act upon what is in the data strategy. Whilst it may seem to increase the number of active participants at an early stage, it does save time in the long run and will make for a better end product. It is also a sign of maturity on the part of those who make a bold move to gain such early engagement, as it demonstrates strong leadership and conviction.

Data is, fundamentally, a strategic asset. As such, it has to be managed strategically in terms of the wider goals and aspirations of the organisation and delivered operationally through tactical activity that the organisation takes day to day. Recognising the person who can provide the right level of sponsorship amongst your stakeholders is key to the success of your data strategy – in terms of both its definition and its execution. A really effective leader in that sponsorship role will play a major part in your being established as the expert in defining and executing the data strategy. It is an essential partnership, part coaching, part challenging, and a key role in translating the data strategy into terminology to secure the investment, executive buy-in and resources needed.

Leadership needs to occur on two levels: firstly, it is about the demonstration of wider understanding to position the data strategy as a key corporate document, for all the reasons outlined above; secondly, it is the leadership role the data strategy itself may provide, resulting in a reset of the corporate ambition due to opportunities that the data strategy presents. This could lead to a rethink either in the ambition of the organisation (pace of delivery or extent of the change anticipated) or in the direction and priorities it has set, based upon the opportunities identified in the course of developing the data strategy; these may be compelling enough to be added in to the corporate strategy or lead to an amendment of the existing content.

The course of devising and developing the data strategy presents a good opportunity for the data, analytics and insight areas to showcase their capabilities. It takes those who may spend a large portion of their time operating in the background firmly into the foreground, and demonstrates how effectively they understand the wider organisation and its goals. Increasingly, there is recognition of the importance of having staff in the data, analytics and insight arena who are comfortable operating at senior levels and can hold their own in both the technical and corporate arena, able to act as intermediaries. This role is becoming one of the most important in the increasingly technical environment in which many analysts are operating. Helping the organisation articulate the business problem and having the wherewithal to define all of, or key parts of, that problem as a requirement takes skill and determination. It is also just as complex to structure the requirement in a way that gets the most effective output from the analyst.

The final form of leadership is fulfilled through consideration of the team that will be tasked with the implementation of the data strategy. Many data strategies have failed to make it through to implementation, often because they lack any guidance for the implementation team or are too theoretical and so gather dust on the shelf.

In the latter case, it is always a salutary lesson when I enter an organisation for the first time and am told that there isn’t a data strategy, only to find a copy filed away and forgotten. I don’t believe anyone writes a data strategy and expects it to fail to see action, but it is all too common an outcome.

It is important, therefore, to provide the leadership that enables the implementation team to see the purpose, vision and direction of the data strategy, and for it to be understood and an implementation plan made to translate it into action.

Figure 2.5 Engaging Leadership model Copyright © Real World Group.

If you think of leadership styles that can be adopted, the process of leading the development of a data strategy plays into all of these in one way or another. This is well illustrated by the Engaging Leadership model by Alimo-Metcalfe and Alban-Metcalfe,8 shown in Figure 2.5. Engaging Leadership is a highly validated model which consists of 14 scales or leadership aspects that are organised into the areas that can be seen in the diagram. Using these 14 scales as a framework, key aspects of effectively leading the development of a data strategy can be understood as follows:

- Building shared vision – in the process of compiling the data strategy, it is likely that inputs from colleagues and other individuals will be required. It is essential that the extent of the change envisaged through the delivery of the data strategy is understood to enable others to contribute to the data strategy: this will enrich the finished product. For example, engaging with the IT function as part of the process will enable that team to understand the direction the data strategy is taking and provide input to facilitate the change. This process is also likely to make people feel more motivated to bring the strategy to fruition, as they have been provided the opportunity to help shape how they feel things should be. It is also valuable as a means to work through what that would mean for staff across the organisation in advance of the data strategy being published.

- Networking – the importance of having a shared vision, as mentioned above, is a key factor in the success of the data strategy: an organisation-wide commitment to its delivery. The use of the behaviours included in this leadership scale, including using political skills to get buy-in and support from influential people within the organisation, as well as the leader utilising the networks they have across the entire organisation, will ensure there is buy-in to the data strategy and also help to bring more diverse views into its compilation.

- Focusing team efforts – the wider engagement outlined above builds organisational commitment to the execution of the data strategy and provides clarity on the part each function of the organisation needs to play for it to succeed. It can therefore be an effective enabler in aligning efforts across the organisation to a common purpose and give a sense of direction to those who need to execute it – as long as it is evident how the strategy translates into execution.

- Inspiring others – the process of taking the lead on developing the data strategy can, at times, feel onerous and challenging. The behaviours that are included in the ‘Inspiring others’ scale refer to gaining commitment to a project or cause through your own passion and determination (whether you are introverted or extroverted). It is important that the leader devising and developing the data strategy has a strong belief in it, clarity of purpose and direction, and that there is clarity of understanding and respect for the approach taken to produce the data strategy to engender a strong commitment amongst team members.

- Acting with integrity and being honest and consistent – the behaviours that are described under these scales are critical: the leader has to be the focal point and act with integrity and consistency throughout the process, willing to have difficult conversations or adapt to others’ views as appropriate through honesty and staying true to the intent to deliver a data strategy that has been collectively developed.

I have mentioned the importance of thinking about the implementation, or execution, of the data strategy above. This is probably the least considered activity when creating any strategy, let alone a data strategy, often because it passes from those who operate in a stand-alone strategy function to either a separate operational group that implements strategy alongside the ‘day job’ or to a dedicated implementation team. It is clear that the less there is continuity in the process from strategy through to execution, the greater is the risk of the strategy failing to be implemented effectively.

The Harvard Business Review published an article by Ron Carucci in 2017 which goes to the heart of why strategies – of all varieties – fail to be executed.9 It stated that research had identified that in the previous year 67 per cent of well-formulated strategies failed due to poor execution – two in three, which demonstrated there was clearly more chance of a strategy failing than it delivering. If this finding isn’t stark enough, the article expanded on causes based on a ten-year longitudinal study into successful executives, undertaken by Carucci’s firm (Navalent): 50 per cent were discovered to have failed within their first year having been unprepared for what faced them – as Carucci related from one interviewee, ‘We fake it till we make it.’

Carucci identified a number of causes for such alarming failures in executive appointments and strategy execution:

- They lack depth in their competitive context.

- They are dishonest or naive about trade-offs.

- They leave old organizational designs in place.

- They can’t handle the emotional toll.

In the article, Carucci referenced research undertaken by Bridges Business Consultancy10 on an annual basis looking specifically at strategy execution amongst firms in Singapore and the USA. The first year Bridges conducted the survey, in 2002, 90 per cent of strategy implementations failed on the measure of achieving at least 50 per cent of the intended outcomes in the time set. In the 2012 survey, 80 per cent of business leaders felt their company was good at crafting strategy, but only 44 per cent saw similar capabilities in execution. Worse still, only 2 per cent believed the implementation would achieve 80–100 per cent of the objectives set. Perversely, the survey found business leaders spent more time on strategy implementation than crafting the strategy itself, and 96 per cent that thought that their bonuses should be tied to successful strategy implementation.

However, the disconnects don’t end there. Seventy per cent of business leaders spent less than a day a month reviewing strategy, and those same leaders believed only 5 per cent of the employees of their organisations had a basic understanding of the company strategy. Middle management was seen as the biggest blocker to successful implementation at 56 per cent, rather than leaders or staff more broadly across the organisation.

The Bridges research in 2012 highlighted three key issues which still resonate today, especially for those who are about to embark on writing a data strategy:

- ensuring staff members take or demonstrate different actions;

- aligning implementation to the company’s culture;

- gaining people’s support.

These three themes will be prevalent throughout this book, and I would recommend you keep them in mind at all times as a reminder to avoid slipping into one or more of these traps at any stage during the process of defining and executing the data strategy.

2.4.4 Agility

You are seeking to produce a data strategy at a time of complex and frequent change. The further the horizons are in the data strategy, the more the environment in which you operate is likely to change. This is not a point to constrain the ambitions you set, and the organisation may determine the period a strategy should cover, but simply to recognise there is a need for flexibility to be built in the longer the time frame of the data strategy. A year or two is relatively easy to visualise and contextualise in the wider organisation; three gives a more forward-looking, visionary feel to the data strategy; five or even ten years is shifting the balance significantly to a crystal ball being required to formulate a large part of the data strategy.

A key factor in devising the data strategy is to recognise that its implementation will require agility on many levels. The way in which it is framed will need to recognise that the organisational dynamics will determine where focus is applied and may mean the implementation resembles a yacht tacking from side to side, whilst remaining steadfast in getting to its final destination.

Even the compilation of the data strategy will require agility, as the knowledge and awareness of wider factors which play in to the way in which the strategy is positioned will go through constant change. This is part of everyday business: however, the challenge (and benefit, I might add) is that the wider stakeholder group that you need to engage with at the outset will bring a range of inputs and views to the team compiling the data strategy, some of which will appear contradictory or lacking sufficient detail to work with – it is beholden on you to demonstrate leadership by tasking those within the team to challenge these and seek clarification, so you can close down any factors which might lead to the strategy being devalued or the implementation being scuppered from the outset.

To stick with the yachting analogy, you need to have gathered all the inputs – maps, tide tables, weather forecasts, experience of the crew, fitness of the yacht itself to undertake the voyage, and of course continuously track these whilst afloat – before setting sail or, in this case, publishing the data strategy.

As you can see, there are a lot of moving parts in the preparation of a data strategy and it is essential to keep moving forward in its development phase. It will almost certainly not prove to be linear, but will require a lot of agility and flexibility, with sections revisited as more knowledge and inputs are captured to refine and inform it.

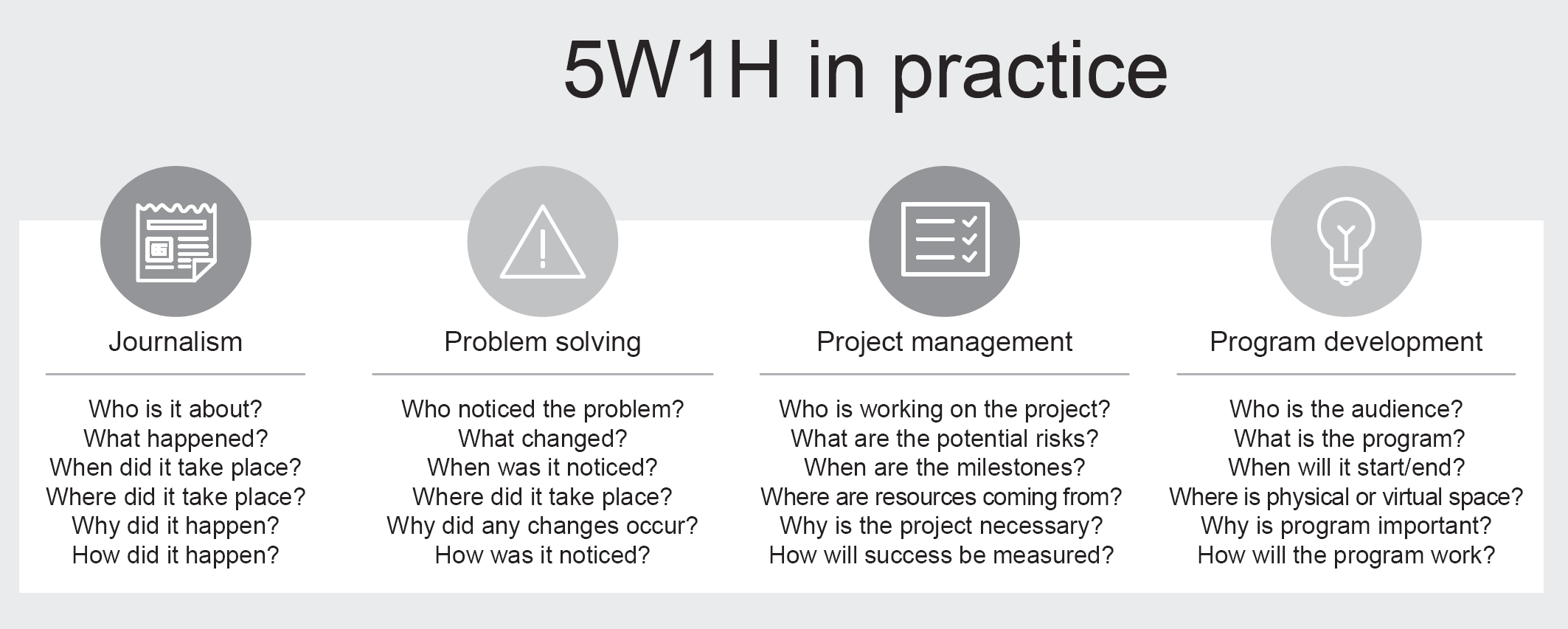

Once the implementation of the data strategy is under way, it will become apparent that the strategy has to be taken as guidance, but with sufficient scope to determine the means of executing it in the implementation phase. This highlights the important differentiation between a data strategy setting direction and the execution of it, which requires significant detail as to the who, what, when, where, why and how – variously referred to as the 5W1H, the Five Ws and How, or the Six Ws.

Figure 2.6 illustrates how to structure the use of the 5W1H methodology in practice, framing a series of questions to suit the nature of the question likely to be asked. In the case of data strategy, it most closely aligns with the approach for programme development, though at various times it may be worth adopting some of the other suggested approaches as you work through everything from checking evidence (akin to journalistic practices), removing barriers or solving problems you encounter, through to assigning tasks within the project itself.

In the implementation phase, there will be a need to recognise resource constraints as well as the wider organisational priorities determining the rate of progress. The data strategy should focus minds on the skills needed, not only in the specialist domains of data and analytics, but also in the wider organisation to be able to implement the strategy and realise the benefits. It is important to ensure the data strategy makes clear the skills gap and treats this as a key input in the successful implementation, as it is arguably more critical to have the right resource and commitment lined up than it is to focus on it as a technical deliverable. Therefore, some understanding of the readiness and maturity of the organisation is key in the process of defining the data strategy, as there is a compelling need to align these with the aspirations set out in the strategy.

The complexities of turning the data strategy into an executable plan are significant. As alluded to above, there are so many moving parts, along with significant shifts and challenges that will be encountered as the organisation progresses through the implementation period, that the need for agility will be critical. I discuss in Chapter 5 the difference between waymarkers and milestones, but the essence of the difference between a data strategy and its execution is in the goals each is seeking to achieve – the former is painting a picture of the future, setting direction and making reference to key points along the way, whilst the latter is taking the strategy and deconstructing it into a series of deliverables with clarity on the 5W1H to achieve the objectives of the strategy.

To use a further analogy, it is akin to preparing a sports team for an upcoming season, determining the right set of skills, tactics, outcomes and formations to be adopted and rehearsing them in a pre-season, prior to moving into the season proper, and having to adapt to the fortunes on the pitch each week to achieve what the team set out to deliver in its goals and objectives during the pre-season. As each match produces an end result there will be reflection, a refocusing if necessary, and a tweak to the formation to be used for the next match, but the intent remains the same. In other words, agility brings learning and adaptation, but doesn’t lead to a shift in thinking or the abandonment of the original strategy, unless the outcomes are so severe it is no longer achievable.

2.4.5 Relevancy

I have touched on relevancy, in terms of staying true to the mission as set out in the data strategy, but also in terms of the need to engage widely with stakeholders and bring some of these into the team to help develop and refine the data strategy.

Figure 2.6 5W1H in practice Karen Cunningham (2019) 5W1H. Fox School of Business, Temple University https://digitalmarketing.temple.edu/kcunningham/2019/08/06/5w1h/.

The key to remember is that the data strategy cannot operate via a siloed approach. Data, and its exploitation, sits at the heart of every business and is increasingly important as its capture becomes ever more complex as the channels through which it is made available and updated expand. The effectiveness of any organisation is now dominated by its efficient use of data, and this has been central to the demise of many household brand names in recent years that failed to recognise the need for a multi-channel experience, or were unable to adapt as more technically savvy organisations entered the market and changed the landscape for good. Any digitally native organisation will tell you that its lifeblood is data, and that a digital strategy is a core element for any organisation today, which makes data especially important.

It is the goal of those who are tasked with devising the data strategy to set it in a critical context to the ongoing existence and success of the organisation.

I have already mentioned the importance of getting a wide range of stakeholders involved from the outset, and bringing some of those into the team to develop the data strategy. This is essential as it brings a range of different perspectives, as well as an interesting challenge to the technical thinking that those with skills in data and analytics will have. Some of this may relate to terminology, understanding and explaining ‘the art of the possible’ (my favourite phrase) to those who may have no awareness or experience of what can be achieved and are therefore limited to the extent of what they can see on their somewhat shorter horizon. However, the blend of understanding what is possible, allied with the realism of how it could be implemented and drive benefit to the organisation, needs commitment from those outside the data and analytics space.

For this reason, engagement from the outset will grow the belief in the data strategy being attainable, and provide critical context of how it can be implemented to deliver the impact that is desired. This is what I mean by the term ‘relevancy’. It is providing the contextual and credible to a data strategy that rightly should contain the aspirational – if the data strategy doesn’t deliver a noticeable difference to the organisation in three, five or ten years’ time then I would ask what it has achieved.

It is also essential that those stakeholder representatives who are actively participating in compiling the data strategy remain closely aligned and in regular contact with their home functions. There is nothing worse than the notion that those that the various functions have provided as conduits are seen to have ‘gone native’, as it destroys their credibility and with it the data strategy too. I would encourage those stakeholder representatives to check in with their functions on a regular basis, to sound out about the latest thinking, challenge preconceived notions of barriers and the ‘that will never work’ naysayers to provide evidence for their negativity; if the latter is proven to have firm foundations, this should be taken back to the project team devising the data strategy. There is no harm in road-testing the data strategy as it is in development, and it is far better to learn as you go than to fail in execution.

I discussed earlier in this chapter the interrelationships with other strategies, and the links between these can also be informed through an effective stakeholder management approach. The breadth of coverage of data means that it will inevitably impact on other strategies and vice versa, so it is essential that you are aware of such strategies either in development or already approved to ensure you are aligned. Using the stakeholders you have engaged through the data strategy will also enable you to identify the connections through their eyes as well as yours, which may help spot something in another strategy which would otherwise not have been so clear to you.

2.5 WHY IS A DATA STRATEGY IMPORTANT?

A data strategy is the opportunity to bring data, one of the most important assets your organisation has, to the fore and to drive the future direction of the organisation. This might seem to be a bold statement – after all, I have said that the data strategy is there to support the corporate strategy achieve its goals – but without clarity on the direction being taken with data in the organisation, it is likely to be much harder to achieve those corporate goals.

Data is the heart of how your organisation operates, linking people, process and technology around common goals, meaning much more can be achieved collectively than if those three operate without using data as the common reference point. Technology moves on quickly – often faster than organisations can keep up – and programmes are launched in many organisations without reference to the data. What is it telling us that we should consider before embarking on the programme? How will we use data to drive the programme? What insight do we want from our data to know whether we have delivered a successful outcome?

Organisations that want to exploit the potential of their data need a coherent way to ensure there is clarity on what is to be achieved, and this is where a data strategy comes in. What it often highlights, though, is that there is a lot of foundation work to be done to get the data into a state to exploit it fully, as fragmentation of data, poor data quality and missing or obsolete data are generally common barriers for all organisations. This in itself is useful, but can often feel like taking a giant stride backwards before being able to go forwards.

There is plenty of evidence of those organisations that are more forward-thinking in their approach to data making better decisions, which, in turn, lead to them outperforming their competitors. This isn’t hidden away from everyone who isn’t in the data profession; it is in well-known journals and newspapers – The Economist, Forbes, New York Times, Harvard Business Review, Financial Times to name a few – let alone the promotional materials released by management consulting and technology firms. However, data strategy is not yet commonplace in management thinking, nor are such strategies necessarily defined or executed (or both) well enough to make them effective. Even if you are relatively late to the data strategy party, it doesn’t mean that you can’t overtake those who arrived before you, let alone those who are still unaware there is a party to be joined.

I would close this chapter by stressing that more strategies fail than succeed, so do not think that this is easy; if it was, everyone would be doing it. I would suggest, though, that it is important that you go into defining a data strategy very aware of the pitfalls and what you need to do to try to avoid them.

Each chapter will conclude with ten key points to take into the next chapter.

These are the ten key take-away points to consider from this chapter as you go forward in your data strategy definition and execution journey.

- There are a number of challenges in positioning the data strategy, especially if this is the first time your organisation has embarked on having one, and it is important you are able to comprehend the environment that led to it being commissioned.

- Clarify what is understood by the desire to create a data strategy so there is common terminology to set expectations of what is to be delivered.

- Identify who ‘owns’ the data strategy in your organisation, and ensure the expectations are clear and roles are defined.

- Consider your stakeholder network – who you need to engage, influence and collaborate with to achieve the goal of defining your data strategy.

- Look to include the management of data and the exploitation of it within the data strategy if possible – this links the investment in the foundations to the potential value generated to the wider organisation.

- Focus on aligning to the corporate strategy. The data strategy is a key enabler to the corporate strategy, but could also present new opportunities to the organisation – consider how these might be introduced and integrated.

- Remember the CLEAR principles – clarity, leadership, execution, agility and relevancy – in preparation for embarking on defining the data strategy. These are key to making sure you are prepared and have evaluated fully your starting point and the direction in which you are heading.

- Ensure you are aligning people, process and technology. All require data in order to be effective, and the better the data, the more effective the organisation will be.

- Test the data strategy as you define it, and use key links into stakeholder groups to get a sense of whether there is buy-in and a willingness to deliver – there is no point defining a data strategy no one wants to implement.

- Data is an asset: position it in such a way that investment, quality and accessibility become understood in that context.

1 Steven Sinofsky, Harvard Business School, 2013.

2 International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation (IFRS), Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting. 2018. https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/conceptual-framework/.

3 Reuters Events, Feeding the Machine: Lessons in Loyalty from Caesars Palace. 2015. https://www.reutersevents.com/travel/revenue-and-data-management/feeding-machine-lessons-loyalty-caesars-palace.

4 IBM, What Is Big Data? More than Volume, Velocity and Variety… 2017. https://developer.ibm.com/technologies/analytics/blogs/what-is-big-data-more-than-volume-velocity-and-variety/.

5 DOMO, Everyone on the Same Page, All the Time. 2018. https://www.domo.com/solution/everyone-on-the-same-page-all-the-time-5.

6 IDC Research/World Economic Forum, How Much Data Is Generated Each Day? 2019. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/04/how-much-data-is-generated-each-day-cf4bddf29f/.

7 Dun & Bradstreet, The Past, Present and Future of Data. 2019. https://www.dnb.co.uk/perspectives/master-data/data-management-report.html.

8 Engaging Transformational Leadership. https://www.realworld-group.com/engaging-leadership.

9 R. Carucci, Executives Fail to Execute Strategy Because They’re Too Internally Focused. Harvard Business Review, November 2017. https://hbr.org/2017/11/executives-fail-to-execute-strategy-because-theyre-too-internally-focused.

10 Bridges Business Consultancy Int Pte Ltd, Strategy Implementation Survey. 2012. www.bridgesconsultancy.com/research-case-study/research/.