3

Assessing Responsibility by Considering Techno-Futures

In order to acquire orientation to act responsibly, the future consequences of actions and decisions are commonly analyzed and assessed from the perspective of responsibility. This model reaches its epistemological limits with regard to the future consequences of NEST. These limits and the possibilities of nonetheless being able to assess NEST futures in terms of the ethics of responsibility are the focus of this chapter. In this context, I will summarize the debate conducted in recent years on this topic and focus it on the research questions of this book. In a sense, this chapter provides a foundation for the suggestion made in Chapter 2 to extend the object of responsibility in the area of NEST.

3.1. Responsibility assessments: introduction and overview

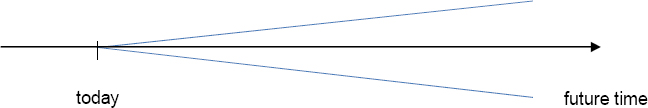

In the past 15 years, there has been a considerable increase in visionary communication on NEST and their impacts on society (section 1.3). In particular, this has been the case in the fields of nanotechnology [SEL 08, FIE 10], human enhancement and the converging technologies [ROC 02, GRU 07a, WOL 08a, COE 09], synthetic biology [GRU 14c, GIE 14] and climate engineering [CRU 06] where debates on responsibility arose. The visions involved refer to a more distant future and exhibit revolutionary aspects in terms of technology and culture, human behavior, and individual and social issues as well. Little if any knowledge is available about how the respective technology is likely to develop, about the products which such development may spawn, and about the potential impact of using such products. Despite the lack of knowledge, lively debates on these visionary technologies emerged. However, the customary consequentialist scheme of creating orientation on the basis of assessments of futures (Figure 3.1) reaches its limits in this connection. The suggestion made in Chapter 2 to extend the object of the debate over responsibility represents a conceptual reaction to this situation. It is now appropriate to give substance to this suggestion and to link it to previous debates such as those over vision assessment [GRU 09b, FER 12] and speculative nanoethics [NOR 07a] and to the first steps toward a hermeneutic analysis of these futures [GRU 14b, VAN 14b], but also to expand on these initial steps. To achieve this, I will differentiate between different consequentialist approaches according to the degree of epistemological quality of our knowledge of the consequences and to the premises they are based on (section 3.3). Responsibility refers here not only to responsibility for future consequences, as is commonly assumed in RRI debates, but also to the responsible utilization of futures in the respective debates and responsibility assessments.

On the one hand, this is true in principle, because prospective knowledge is epistemologically precarious in general (section 3.2) which is the main challenge for enabling sound argumentation rather than mere speculation. Having touched upon this issue at many points in the preceding chapters, it is now the task to deal with the precarious nature of prospective knowledge in a more substantial and systematic way – as well as to ask for patterns of deriving orientation from prospective knowledge (section 3.3).

On the other hand, this is most notable in prospective knowledge that is particularly problematic or even largely speculative, as is typical in the case of NEST. Prospects of the future are often controversial, divergent or even contradictory with respect to their results and may be hotly contested in the case of positive and negative visions in NEST fields. In this case, the consequentialist scheme using arguments about the consequences of NEST (Figure 3.1) does not function any longer, which in particular has substantial consequences for policy consultation in this field (section 3.4). In these constellations, this gives rise to a rethinking of policy advice and to a different manner of consideration of the role of futures. The question as to responsibility for meanings attributed by means of the use of techno-visionary futures then assumes the primary function in the search for orientation (section 3.5).

3.2. Brief remarks on the epistemology of prospective knowledge

Knowledge about the future or assessments of what is to come differs epistemologically from knowledge about the present and past. The possibilities to verify this knowledge are also different (section 3.2.1). The designation of statements about the future as constructions (section 3.2.2) makes it possible, however, to indicate a means by which epistemological assessments can be performed.

3.2.1. The epistemologically precarious character of prospective knowledge

Prospective knowledge as the result of studying the future, e.g. in the form of model-based energy scenarios, or as the result of complex Delphi processes, qualitative considerations of experts, or participatory workshops on the future, is usually obliged to maintain the standards of science. This means that these results can be grounded in valid arguments. In case of doubt, the entire chain of argumentation that they are based on can be made transparent and subject to critical examination. Precisely, this distinguishes scientific knowledge from non-verifiable knowledge, such as alleged secret knowledge. The usual procedures of assuring scientific standards and validity of scientific knowledge cannot, however, be applied to prospective knowledge:

- – the possibility of employing experiments and measurements to perform an empirical verification is not available. Statements about future developments or events cannot be verified by observation in reality or in a laboratory. Neither is time traveling possible nor is fast-forwarding a means to play through future developments in a laboratory;

- – an empirical verification is frequently replaced by a virtual one using model-based simulations. The model that the simulations are based on can, however, only be validated with reference to the past and present, not with reference to the future. The results of simulations can be a component of an argumentative verification, but they reach fundamental limits because they can only assume, but not verify, the validity of the models for the future;

- – the logical deduction of prospective knowledge from bodies of knowledge in the present also fails. Even if there were clear laws governing social matters, extending them into the future would fundamentally necessitate further premises (such as assumptions over the stability of this knowledge in the future, too), whose justification cannot be decided either empirically or logically [GOO 54];

- – correspondingly, the methodological conception of the falsification of scientific hypotheses and the approximation to truth by promoting scientific knowledge through efforts at falsification in the sense of Karl Popper [POP 89] cannot be applied to prospective knowledge.

Prospective knowledge is therefore in a specific sense epistemologically precarious. Yet, since we cannot forego the standard of verifiability if a society does not want to get involved in pure prophesying, there has to be another procedure for checking validity and assuring quality. The questions of what the object of argumentative discourse between proponents and opponents of prospective statements can be are decisive, and if anything can and should be defended against doubt.

3.2.2. Futures as social constructs

We make statements and prognoses about the future, simulate temporal developments and create scenarios, formulate expectations and fears, set goals and consider plans for their realization. All this takes place in the medium of language [KAM 73] and is thus in the present. Forecasters and visionary writers cannot break out of the present either, always making their predictions on the basis of present knowledge and present assessments. Future facts or processes can be neither logically deduced [GOO 54] nor empirically investigated (section 3.2.1). The only things that are empirically accessible are the images that we make of the future, but not the future itself that will at some time become the present. For this reason, we can talk about possible futures in the plural, about alternative possibilities for imagining the future and about the justification with which we can expect something in the future. These are always present futures and not future presents [LUH 90]. Therefore, if we talk, for instance, about cyborgs or far-reaching human enhancement which might be possible in the future, we are not talking about whether and how these developments will really occur but how we imagine them today – and these images differ greatly. Futures are thus something always contemporary and change with the changes in each present. “A future is thus not something separate from the present, but a specific part of each present” [GRU 06]1.

Futures do not exist per se, and they do not arise of their own accord. Futures, regardless of whether they are forecasts, scenarios, plans, programs, visions or speculative fears or expectations, are designed using a whole range of ingredients such as available knowledge, value judgments and suppositions. The designing of futures is purposive action, intended especially to provide orientation. This construct character of futures is the origin of the diversity of images of the future in NEST fields and beyond. It is essential for scrutinizing them with regard to content and quality.

In the case of differing and controversial futures, discourse between opponents and proponents is the method to debate and scrutinize the argumentative quality of futures. Because of the social construct character of futures, their argumentative quality will strongly depend on what was put inside their construction. What can be said with validity is not whether claims about futures will come true but only whether their coming true can be expected on the basis of present knowledge and a present assessment of their relevance [LOR 87]. The question arises as to the ingredients that are used in the shaping of futures and in which way these ingredients have been assembled and composed in arriving at the respective statements about the future.

As far as their knowledge structure is concerned, futures are initially opaque constructs consisting of highly diverse elements. In a rough approximation, the following gradation of knowledge and other components can initially be made:

- – present knowledge which is proven according to accepted criteria (e.g. of the respective scientific disciplines) to be knowledge (e.g. according to the issue at stake from the field of nanotechnology, engineering and economics);

- – estimates of future developments that do not represent current knowledge but that can be substantiated by current knowledge (e.g. demographic change and energy needs);

- – values and normative expectations about the future society, future relations between humans and technology or between society and nature, etc.;

- – ceteris paribus (all other things being equal) conditions, whereby certain continuities – business as usual in some sense or a lack of disruptive changes – can be assumed as a framework for the prospective statements;

- – ad hoc suppositions which are not substantiated by knowledge, but taken as given (e.g. the future validity of a German phase-out of nuclear energy, or the non-occurrence of a catastrophic impact of a comet on the Earth);

- – utopian ideas of worlds where everything could be different in the future, speculative proposals for futures worlds, science fiction stories and other imaginations.

Future constructs are thus created in accordance with available knowledge, but also with reference to assessments of relevance, value judgments and interests, and may also include mere speculation. The construct character of futures can thus be exploited by those representing specific positions on social issues, substantial values and particular interests in order to produce future visions corresponding to their interests and to employ these to assert their particular positions in debates [BRO 00]. This leads to the question of whether and to what extent one can work against the usurpation and instrumentalization of NEST futures by evaluating images of the future in a comparative manner according to scientific and argumentative standards.

Whoever raises claims of validity and to be avoiding arbitrariness or instrumentalization when speaking about future developments has to name the preconditions to be assumed as the basis for making a well-grounded statement about the future. A discourse about questions concerning the argumentative quality of future statements is thus turned into a discourse about the knowledge components and normative preconditions as ingredients of the composition, and about the methodological integration. A dispute about the quality of techno-visionary futures therefore does not refer to the events predicted to come about in a future present but to the reasons for the respective future that can be given on the basis of current knowledge and current judgments of relevance. These reasons must then be deliberated and weighed in discourse.

While reliable and very precise prospective statements can be found in many scientific prognoses such as in astronomy, in social issues, which is the rule in RRI in connection with new forms of technology, there is frequently a high to very high level of uncertainty of prospective knowledge. These uncertainties cannot be reduced, or only to a limited degree, by using better methods of studying the future. They are an expression of the fundamental open-endedness of the future. Future developments, such as in the use of the different forms of NEST technology and their consequences, cannot be calculated from the combination of natural laws and today’s data according to the Hempel-Oppenheim model of prediction [HEM 65]. This is the case since future developments depend on decisions that will not be made until sometime in the future and that cannot be anticipated today. This open-endedness of the future is synonymous with its malleability and the opposite model of a deterministic understanding of history. There is simply no reason to complain about the poor predictability of the future. The only future that can be predicted is that which is already certain today and that results from a combination of today’s data with a definite regularity [KNA 78]. Predictability and the ability to shape developments are mutually exclusive.

Yet, if the open-endedness of the future, and thus its capacity to be shaped, place clear and principal limitations on the frequently formulated expectations and desires for predictability, then the question arises of what this means for gaining orientation for today’s decisions in a consequential manner. In this context, it is important to emphasize that gaining orientation certainly does not require futures to be predictable so that we can utilize them as a boundary condition in order to make an “optimal” decision in a rational choice approach to decision-making theory. Rational orientation can be derived from open and diverse futures as is shown by, for instance, the scenario approach (section 3.3.3). We thus have to distinguish between reliable predictive knowledge and reliable orientation on the basis of the available and partly very uncertain predictive knowledge. This distinction permits us to identify different forms of gaining orientation on the basis of predictive knowledge according to the various degrees of its epistemological quality, which is the task of the following section.

3.3. Responsibility for NEST: the orientation dilemma

In modern society, political and economic decisions are mostly orientated by considerations on the future [LUH 90]. Taking current problem areas and diagnoses as starting point, we use futures studies, projections and debates to get orientation for today’s decision making [GRU 09b] (see Figure 3.1; e.g. in the field of technology assessment). Debates about the future are an essential medium of modern societies’ self-understanding and governance – and futures reflections and futures studies are important means of providing orientation for society and decision makers.

Figure 3.1. The consequentialist paradigm of technology assessment (from [GRU 12b])

This in particular holds true in the field of responsibility. As has been shown in Chapter 2, the future consequences and impacts of actions and decisions are subject to responsibility reflections in the NEST fields. To make the EEE approach (section 2.3) work, responsibility assessments for the cases under consideration have to be performed covering all three dimensions. For assessing responsibility, prospective knowledge about the presumed consequences of actions in a consequentialist type of reasoning is needed. This must cover the “right impacts” of the new technology [VON 12] as well as unintended side effects [GRU 09a] and other impacts such as resources needed or boundary conditions to be fulfilled in order to establish promising innovation pathways.

The considerable diversity, if not divergence, of many future prospects in the NEST fields is prima facie a threat for the desired orientation. In cases of divergence, it gives rise to significant doubt as to whether we can learn from them at all for decision-making processes by providing responsibility assessments. If the statements differ so widely that we suspect large arbitrariness, the condition of the possibility of giving orientation is no longer met. As is well known, it is impossible to draw reliable conclusions from contradictory or arbitrary premises. Even reflexive governance including its wide opportunities of learning during the process [VOS 06] would not be able to make sense of this extreme constellation.

The open-endedness of the future and the associated uncertainty of predictive knowledge (section 3.2) do not inevitably have to stand in the way of deriving conclusions to guide our actions. Plausible conclusions for the present can also be drawn from uncertain or open-ended futures, above all by using the scenario approach. It is particularly decisive that the respective item of predictive knowledge may not be completely arbitrary, for otherwise only completely arbitrary and thus, from the perspective of rationality, worthless conclusions would be possible. A dilemma of orientation arises (section 3.4): in a situation with diverse and divergent futures, the need for orientation seems to be particularly high. However, simultaneously, diversity and divergence of futures hinder drawing orientating conclusions from that field of futures.

This chapter takes a closer look at challenges to policy advice that appear to be specific to the field of techno-visionary sciences and NEST [GRU 13a] (section 3.3.1), followed by the identification of an orientation dilemma (section 3.3.2).

3.3.1. Challenges to providing orientation in NEST fields

Techno-visions address possible futures for techno-visionary sciences and their impacts on society at a very early stage of development where little if any knowledge is available about future consequences. According to the control dilemma [COL 80], it is then extremely difficult, if not impossible, to shape technology. Lack of knowledge could lead to a merely speculative debate, followed by arbitrary communication and conclusions [NOR 07a].

The arbitrariness problem

A fundamental problem with far-reaching future visions is the inevitably high degree to which material other than sound and reliable knowledge is involved. In many cases, entire conceptions of the future, or aspects of it, are simply assumed due to a lack of knowledge. Huge uncertainties enter the field – these are gradually and imperceptibly transformed, first to possible, then plausible and finally probable development paths: “As the hypothetical gets displaced by a supposed actual, the imagined future overwhelms the present” [NOR 09, p. 273]. Indeed, it is not unusual in the field of NEST to operate with second- or third-level conditionality, namely, when certain consequences are assumed to occur possibly as a consequence of the use of visionary innovation that itself might become reality only possibly, if the respective technical development were to take place in the direction envisaged and would lead to the intended success. Obviously, this hierarchy of conditional statements with unclear epistemological status results in determining objects of RRI debates in a merely speculative manner.

Consider, for example, the different views on converging technologies by Dupuy/Grinbaum [DUP 04] and Roco/Bainbridge [ROC 02]. The future prospects of converging technologies show the maximum conceivable disorientation and oscillate between expectations of paradise and catastrophe. If there were no methods of assessing and scrutinizing diverging futures in epistemological terms, the arbitrariness of futures would destroy any hope of gaining orientation in the consequentialist paradigm. This was the primary concern of the criticisms on speculative nanoethics [NOR 07a, GRU 10a]. This arbitrariness problem constitutes a severe challenge and raises doubts about whether such an endeavor could succeed at all.

The ambivalence problem

Visions are an established (and perhaps, in some respect, necessary) part of the scientific and technological communication. In general, they aim to create fascination and motivation among the public but also in science, increase public awareness on specific research fields, help motivate young people to choose science and technology as fields of education and as careers and help gain acceptance in the political system and in society for public funding.

However, the concrete visions used to reach these goals often show a high degree of ambivalence [GRU 07a]. Promised revolutionary changes by introducing new technologies do not only create fascination and motivation but also concern, fear or objection. There might be, in the course of time, winners and losers, there might be unexpected and possibly negative consequences and, in any case, there will be a large degree of uncertainty. Revolutionary prospects do not automatically lead to positive associations but might cause negative reactions. Using futuristic visions might, as a consequence, lead to backlash and rejection instead of fascination and acceptance.

This ambivalence shows itself, for instance, in the vision of a “New Renaissance” [ROC 02]. There, the dawn of a new Renaissance – as the result of dramatic scientific and technical progress – is treated as a positive utopia, in which Leonardo da Vinci is seen as the ideal of a modern human being. The New Renaissance is announced as an age in which humanity’s problems will be solved by overcoming the fragmentation of science and society through convergence on all levels. But the announcement of a New Renaissance can also be read completely differently. Though its prototype, the Renaissance of the 16th century, was in fact the epoch of Leonardo, it was also a period of uninhibited violence (one recalls the Sacco di Roma, which found its artistic expression in Michelangelo’s awesome depictions of the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel), of the Peasant Wars, the religious wars and of intolerance, a violent redistribution of wealth, and upheavals. Today’s perception of the Renaissance as a bright age of rationality is a construct of the European Enlightenment – by far the great majority of Leonardo’s contemporaries would have experienced it completely differently [GRU 07a, GRU 12b].

There is a systematic reason behind this ambivalence, which is related to the issue of uncertainty. Far-reaching, highly positive expectations can often be easily changed into dark, dystopian scenarios: “Tremendous transformative potential comes with tremendous anxieties” [NOR 04, p. 4]. A famous example of this reversal of positive expectations into sinister fears has been provided by Bill Joy [JOY 00]. In his future projection, self-reproducing nanorobots are no longer a strong positive vision which is supposed to contribute to the solution of humanity’s gravest problems [DRE 86] but are interpreted as a nightmare, leading to a complete loss of control of humans over technology (see Schmid et al. [SCH 06] and section 5.4). The same technical basis – molecular assemblers, nanomachines and nanorobots – is embedded in totally different future projections between salvation and apocalypse. The futuristic visions attributing societal meaning to NEST are not determined by the technical ideas. Rather, societal expectations or fears, values, philosophical or ethical ideas about humankind’s future, etc., are entering the game and exert heavy influence on ongoing RRI debates – this is exactly the reason for postulating to extend the object of responsibility and to explicitly consider this effect of meaning-giving in RRI debates (Chapter 2).

Lack of transparency

Visionary futures are frequently created by scientists and science managers who at the same time are stakeholders with their own interests. Given the considerable impact of techno-visions on the way new technologies are perceived in society and in politics, and given that they are an important part of their governance (see section 1.2), they should be subject to democratic debate and deliberation. The significant lack of transparency and unclear epistemological status of futuristic visions are, however, obstacles to transparent democratic debate. The construct character of futures can be exploited by those representing specific positions on social issues, substantial values and specific interests such that future visions are produced that reflect their interests and can be employed to assert their particular positions in debates [BRO 00].

The non-transparent nature of the visions communicated in public debate hinders open democratic deliberation (this also holds for scenarios, see acatech [ACA 16] for the field of energy scenarios). Techno-futures suggested by scientists, science managers or science writers could dominate social debates by determining their frames of reference. In this case, visionary scientific and technological futures could endanger public opinion forming and democratic decision making, thus perhaps constituting a new form of hidden expertocracy. Against the background of normative theories of deliberative democracy, there is therefore a considerable need to improve transparency in this field.

3.3.2. The orientation dilemma

Scientific and technological progress leads to an increase in the options for human action. Whatever was once inaccessible to human intervention, whatever had to be accepted as uninfluenceable nature or as fate now becomes an object of technical manipulation or design. This is an increase in contingency in the conditio humana, a broadening of the choice of options, and, with it, a diminution of human dependency on nature and on humanity’s own traditions [GRU 07a]. It is this increase in options for action, including the ambivalences of most of the new options [GRU 09b], which leads to a considerably increased need for orientation.

Visionary and far-sighted communication in NEST fields can be interpreted to serve different functions in the context of coping with increasing contingency [GRU 07a]:

- 1) Catalyst function: communication about possible, expected or feared futures is in itself a catalyst and a pacemaker for increasing contingency. Previously unquestioned certitudes (e.g. the abilities or capabilities of a healthy human eye and its limits) are already dissipated by the fact that future technical possibilities for improvement are discussed throughout society. Independent of the question of whether and when these possibilities could be realized, possible alternatives and options of choice come into view through the visionary communication on the future itself. Traditional certitudes are eliminated, and new occasions of choice are created without their technical preconditions already having been established. The recent debate on human enhancement can be taken as an excellent manifestation of this catalyst function of techno-visionary communication (see Chapter 7);

- 2) Indicator function: the occurrence and intensification of techno-visionary communication in NEST debates indicates the ongoing erosion of traditional certitudes. Such communication involves the disintegration and dissolution of certitudes acknowledged so far and the appearance of new questions such as whether and how the naturalness or malleability of the human body and mind can be observed empirically. Techno-visionary communication is an indicator of increasing contingency and could, therefore, be investigated empirically in order to get some more insights into the spreading of the respective ideas over society and the ways of changing the attitudes of people;

- 3) Orientation function: communication on the future, including techno-visions, can be seen also as an attempt to regain orientation in view of new options of choice and the corresponding uncertainty and is the standard model of how modern societies seek orientation. If we were to succeed in bringing about orientation for decision making by arriving at societal agreement on future scenarios that are planned, desirable or to be prevented, then the situation of increased contingency would be mastered constructively. This, however, is a normative expectation concerning the role of communications of the future [LUH 90] (see also section 3.4).

Obviously, these three functions are categorically different. The catalyst and the indicator functions are – in principle – empirically observable and could be investigated empirically by means of social sciences. The orientation function, however, is a normative expectation provided by the theory of modern societies [BEC 92, LUH 90]. Whether it would really be possible to regain orientation by debates on possible future scenarios does not seem to be self-evident because the plurality of modern societies in normative respect will directly affect the judgment of future developments and prevent easy consensus [BRO 00]. The well-known societal conflicts will also enter the field of future considerations and assessments, in particular in case of highly speculative knowledge about future consequences of NEST. Even worse, NEST developments and debates that attempt to bring about orientation through techno-visionary communication could easily cause new orientation problems instead of providing solutions (see Grunwald [GRU 07a] for the case of human enhancement). Thus, the normative function of future communication mentioned above is in danger of being merely wishful thinking. If a negative techno-vision stands against a positive one, uncertainty and confusion could even be increased instead of being reduced. An orientation dilemma may, therefore, be formulated in the following way: Attempts to provide orientation by techno-visionary futures can increase disorientation.

This intermediary result is fatal because it seems that there will be no chance of regaining orientation: relying on traditional values is no longer possible because of the increased contingency, and taking the way via techno-visionary communication would be impossible because of the ambivalences shown above. In the remainder of this chapter, we will try to remedy this fatal situation by reconsidering the role of visions in NEST debates from a different angle [GRU 07a], based on a differentiated picture of the possibilities to extract orientation from assessing futures.

3.4. Three modes of orientation

The threefold picture of different types of orientation drawn from future assessments given below [GRU 13c] extends the current picture working with the main distinction between forecasts and foresights. It will be shown that the orientation dilemma (section 3.3) can be overcome by considering a hermeneutic mode of orientation related to the dimension of meaning of the respective NEST instead of the familiar consequentialist approach concerned with future consequences of NEST developments (section 3.5).

3.4.1. Prediction and prognostication: mode 1 orientation

Orientation by considerations on the future was and is often introduced as if the imagination of future developments could create reliable predictions which considerably reduce the open-endedness of the future. These predictions are then expected to direct pending decisions, e.g. concerning regional development or the expansion of infrastructures, so that they ideally fit into the predicted futures. Predictions can be made in decision-making processes following the rational choice paradigm by using simple input data to look for a “good”, “right” or even “optimal” decision.

Predictive futures prognosticate a specific development for the futures with a more or less high accuracy. If we use the metaphor of future cones, which is frequently applied in the field of futures studies, a prediction would have an opening angle as small as possible (Figure 3.2), ideally zero degrees.

Figure 3.2. Cone of futures with small opening angle, close to the prognostic ideal

Research and experience clearly shows that accurate predictions cannot be made for complex societal issues – this diagnosis, based not only on empirical evidence [SLA 95] but also on theoretical consideration, will not be repeated here. In NEST fields, any prediction about future consequences of their development, use and disposal would obviously be ridiculous because of their enabling character (see section 1.3). Future consequences of NEST will strongly depend on developments yet to happen and decisions to be made in the future which themselves cannot be predicted because of the absence of regularities and laws which would be required as basis of deductive reasoning [HEM 65].

A theoretical argument for skepticism about the hopes that the above-mentioned problem can be overcome by more research originates from a well-known epistemological consideration. The communication of societal futures is an intervention into further development and changes the constellation for which it was created. Thinking about the future is not possible from a contemplative observer’s perspective; the producers of knowledge about the future are part of the system for which they construct futures. Here, the familiar problem of “self-fulfilling” and “self-destroying prophecy” ties in [MER 48, WAT 85].

Mode 1 orientation often works well in the field of natural science, e.g. in astronomy and – not always – in weather forecasting. However, in the case of social issues, things are epistemologically quite different from the natural science constellation because of the absence of social laws in contrast to natural laws, and because of the intervention issue mentioned above. Thus, predictive orientation is almost inapplicable in technology assessment [GRU 09a] and RRI. The reason why it has been briefly described here in spite of its inapplicability to our consideration of NEST is to get the full picture (see Grunwald [GRU 13c] for a more detailed analysis).

3.4.2. Scenarios and the value of diversity: mode 2 orientation

Mode 2 orientation drawn from futures assessments has to cope with a higher diversity of future prospects. This has been done successfully in the field of futures studies, differentiating between forecasts and foresight [RES 98, BEL 97, SLA 05]. While forecasting corresponds to the mode 1 approach above, foresight aims to provide a broader and more explorative view of futures, acknowledging their necessary diversity and open-endedness. Frequently, foresight ends up in a set of scenarios, e.g. for the energy system, regional development or the possible future development of economic branches. The opening angle of the respective future cone – to return to this metaphor – may be much larger but still must not be too large. The orientation value of the scenario approach excludes a large set of possible futures as implausible and restricts further considerations to the space of remaining plausible futures. Often, this space is defined as the region between a “worst case” and a “best case” scenario (see Figure 3.3).

Conclusions from the diverse futures are often drawn in the form of robust action strategies, i.e. strategies which are promising in all of the plausible futures considered [BIS 06, LIN 03]. If, for example, strategies for action toward sustainable development are designed for a bundle of different futures and suggest positive sustainability effects for each of them, this contributes to identifying robust actions in terms of sustainability governance [VOS 06]. Thus, the scenario approach allows deriving knowledge for action in spite of a certain diversity of futures. By applying the scenario approach, it is necessary to form opinions and take decisions about values and priorities, which opens up possibilities to constructively use the diversity of futures for democratic debate and to avoid technocratic closure of the future.

Figure 3.3. Cone of futures with medium opening angle between worst-case and best-case scenarios

The field of energy futures provides an illustrative example. In the field of energy futures and related emission scenarios, we can find various degrees of diversity [KEL 11b]. For decades, incompatible and diverging energy futures have been discussed without exact knowledge on which futures are to what extent backed by knowledge, where the areas of consensus are and where the futures are determined by assumptions on boundary conditions and societal developments that are poorly or not at all verified. The diversity of energy futures is significant: we are not talking about things like error bars to illustrate the discrepancies among them but about deviations of factors of two to four, both regarding the expected total energy demand in 2050 and its expected distribution between different energy carriers [GRU 11c]. Even in this case, which involves diverse futures, the scenario approach allows drawing some action-guiding orientation. However, caution is needed in order to avoid overinterpretation and resulting fallacies [DIE 14].

Of course, the use of diverse futures for orientation purposes in the scenario approach is not without presuppositions. The precondition for mode 2 orientation to be achievable is that the diversity of the set of futures considered is limited in some sense (see Figure 3.3). It must be possible to identify a corridor of sensible assumptions about future developments: within the corridor, several future developments are regarded plausible but the field outside the corridor may be excluded from further consideration for argumentative reasons. For example, in the field of energy scenarios, there is high diversity but not arbitrariness because extreme scenarios are rendered implausible. It is exactly this precondition of relying on a corridor of plausible futures which limits the applicability of the mode 2 approach – and provides motivation to look beyond because this precondition is not fulfilled in most NEST fields.

3.4.3. The value of divergence: mode 3 orientation

But what can be done if there are no well-argued corridors of the envisaged future development or if proposed corridors are heavily contested? If, metaphorically speaking, the opening angle of the respective future cone is very large, perhaps close to 180°, the whole space of futures must be considered (Figure 3.4). However, this implies an arbitrariness of prospective knowledge. Neither mode 1 nor mode 2 orientation would then work because of the laws of logics: no sensible output can be produced from contradicting or arbitrary input.

Figure 3.4. Cone of futures with large opening angle in the absence of reliable future knowledge

Even in this seemingly disastrous situation, orientation building by analyzing futures is possible. The corresponding mode 3 approach, however, describes a completely different mechanism of providing orientation compared to what we normally expect from futures studies and which is expressed by mode 1 and mode 2 approaches [GRU 13c]. The only orientation this mode can provide is a semantic and hermeneutic structuring of a basically open future to allow a better informed and reflected debate for preparing decision making. Mode 3 orientation can only be understood as an offer to improve the conditions of an open, transparent, and democratic deliberation and negotiation by the hermeneutic self-enlightenment of RRI debates.

To trace the possibility of such mode 3 orientation, the origins of the divergence of futures must be considered. Futures studies, narratives and reflections are trapped in the “immanence of the present” [GRU 06]. Visions of the future are social constructs created and designed by people, groups and organizations at, respectively, determined points in time [SEL 08] resulting from a composition of ingredients in certain processes (section 3.2). The divergence of visions of the future results from the consideration of controversial and divergent knowledge bases and disputed values during their creation: the divergence of futures mirrors the differences of contemporary positions, the diversity of attitudes and reflects today’s moral pluralism. Thus, uncovering these sources of diverging futures could tell us something about ourselves and today’s society. Mode 3 orientation implies a shift in perspective: instead of considering far futures and trying to extract orientation out of them, these stories of the future now are regarded as “social texts” of the present including potentially important content for today’s RRI debates.

This change in perspective provides an option to substantialize what has been postulated in Chapter 2 as to extending the object of responsibility. Bringing together the idea that the assignment of meaning to NEST is, among other mechanisms, done by relating new technology to visionary futures (Chapter 1), and asking now for the contemporary meaning of these visionary futures makes clear that a hermeneutic assessment of techno-visionary futures will also serve RRI debates by addressing the question of the challenges of responsibility behind the creation, communication and deliberation of techno-visionary futures in NEST debates2.

3.5. The hermeneutic approach to techno-visionary futures

Thus, if the customary consequentialist approach does not function for NEST, we must ask which other approaches can provide what orientation and how. That orientation is necessary and has been established (section 1.2), but possibility is not a logical consequence of necessity. The more speculative the considerations of the consequences and impacts of techno-visionary sciences, the less they can serve as direct orientation for concrete (political) action and decisions. Instead, conceptual, pre-ethical, heuristic and hermeneutic issues then assume greater significance. The primary issue is then to clarify the meaning of the speculative developments: what is at issue; which rights might possibly be compromised; which images of humankind, nature and technology are formed and how do they change; which anthropological issues are involved; and which designs for society are implied in the projects for the future? What remains once any claim to anticipation is abandoned is the opportunity to view the lively and controversial debates about NEST and other fields of science or technology not as anticipatory, prophetic or quasi-prognostic talks of the future but as expressions of our present time. The subject of investigation is not what is being said with varying justification about coming decades, but what is revealed about us by the fact that these debates are happening today.

Responses to this situation included proposals for vision assessment [FER 12], the critique of speculative nanoethics [NOR 07a], the outline of an explorative philosophy [GRU 10a] – plus various, mostly scattered references to an analytical discourse or hermeneutic approach concerning the evaluation of emerging technologies [VAN 14b, TOR 13]3. Common to these approaches is the move away from the consequentialist perspective and from knowledge claims of likely consequences, where such claims consist only of epistemologically unclassifiable speculative expectations of the future, or of visions and anxieties the plausibility of which remains precarious. The following set of questions unfolds the expectations concerning a hermeneutic approach [GRU 14b]:

- – what do current developments in science and technology signify for the relationship between humanity and technology, for humanity and nature, how do they alter or transform these relationships and “what is at stake” in ethical, cultural and social terms? How are social problems and appropriate solutions presented, and how are these formatted as more or less technical problems?

- – how is philosophical, ethical, social, cultural, etc., significance attributed to techno-scientific developments? What role do (visionary) techno-futures play in this context?

- – how are attributions of meaning being communicated and discussed? What roles do they play in the major technological debates of our time? What forms of communication and linguistic resources are being used and why? What extralinguistic resources (e.g. movies and works of art) play a role in this context and what does their use reveal?

- – why do we thematize techno-scientific developments in the way we do and with the respective attributions of meaning rather than in some other way? This is where the hermeneutic analysis of the NEST debates assumes a time-diagnostic function and can contribute to self-understanding in and of the present;

- – what is the hermeneutic significance of the traditional ways of reflecting technological development (prognostication and scenario methods)? How are hermeneutically significant constellations concealed, so to speak, by what is overtly presented in terms of technology trends, time lines, roadmaps and charts?

- – how does a discourse about technological futures acknowledge humans as historical beings? What concepts of the future are brought to bear when the future is presented either as though it were an object of technical or political design or as what will contingently come about and will always fall short of our best efforts to assume historical responsibility and bring about a better world?

- – what is the notion of presence that becomes salient when one adopts a hermeneutic approach and finds that there is always only the present horizon of meaning for discourse about technology? If the present is more than a present point in time but instead possesses the temporal extension of our presently given world, how does this contingently given, persistent yet perhaps unsustainable world compare to future worlds and alternative worlds? Does a hermeneutic approach afford the distinction between what will likely be the case in the present world at a later stage and the event that may bring about a future world?

The hermeneutics of more or less speculative visions should address not only the cognitive but also the normative content of the visionary communication, which are both culturally influenced. In normative terms, this would mean preparatory work for ethical analysis. As regards cultural issues, hermeneutic analysis could result in a better understanding of the origins and roots of the visions by uncovering underlying cultural elements. An example of this type of analysis can be found in the DEEPEN project [DAV 09, MAC 10, VON 10]. One of the findings was that cultural narratives such as “Opening Pandora’s box” and “Be careful what you wish for” also form the backdrop to many of the visionary public debates and concerns.

Thinking about these issues is obviously not aimed at direct policy action but is more about understanding what is at stake and discussed in the NEST debates. In this way, hermeneutic reflection based on philosophical and social science methods such as discourse analysis can prepare the groundwork for anticipatory governance [GUS 14b] informed by applied ethics and technology assessment. Ultimately, this may promote democratic debate on scientific and technical progress by investigating alternative approaches to the future of humans and society with or without different techno-visionary developments.

This book presents several case studies for which a hermeneutic analysis has already been initiated, partly without it being referred to as such in the original publications. The reflections on nanotechnology (Chapter 5), on autonomous robots (Chapter 6) and on enhancement technology (Chapter 7) are thus reinterpretations that have been motivated by the concept of the hermeneutic approach. Similarly, the reinterpretations do not constitute complete hermeneutic analyses but only initial steps to demonstrate and illustrate the conception.