6

The Avoided Cooperation

The two structuring social fields of the cluster are spanned by internal struggles that limit exchanges between accredited members. This final chapter then focuses on the form of the network produced by these strained fields. Beyond the words of the respondents or the sponsors who testify to a lack of cooperation, carefully observing and categorizing the nature and volume of relations in the cluster makes it possible to realize the extent to which cooperation is finally avoided.

6.1. A patchy local network

While the local shape of the network is important in understanding the types of interactions that take place within the cluster, the importance of external relations also shows the problems posed by geographical proximity.

6.1.1. What type of organizations for what type of interactions?

Using the network analysis method, relationships within the cluster could be mapped from a significant sample. Many examples in network literature are based on researching groups with defined boundaries (school classes, offices, etc.). In contrast to observing a network in a business with well-defined boundaries, the cluster poses problems in identifying boundaries, as it involves sectoral and/or territorial delimitations (Bernela and Levy 2017, p. 5). Hence, in the context of a perimeter marked by a diversity of subjective imprints that blur its lines, the choice has been made to rely, on the one hand, on its institutional contours, constructed and conveyed by the Genopole structure, and, on the other hand, on the unity of place represented by the Evry region. The intermediation structure recognizes the fact that companies and laboratories belong to the biocluster in three distinct ways: (1) by accrediting them; (2) by listing them in the annual biocluster directory; and (3) by communicating with them institutionally through promotional events and brochures. As a result, the network includes 56 companies (41 VSEs, 14 SMEs and a private organization providing work experience training in biotechnology professions), 20 laboratories, 13 of which are attached to the local university, two private laboratories, a patients association, the hospital and a scientific culture association.

Table 6.1. Typology of network structures

| Structure attributes | Corpus of data | % | Sample | % |

| Patients association | 1 | 1% | 0 | 0% |

| Scientific culture association | 1 | 1% | 1 | 2% |

| Hospital 1 | 1% | 1 | 2% | |

| Small private laboratory (< 50 people) | 2 | 3% | 2 | 5% |

| Small public laboratory (< 50 people) | 9 | 11% | 4 | 10% |

| Medium-sized public laboratory (50–150 people) | 7 9% | 6 | 14% | |

| Large public laboratory (150–300 people) | 2 | 3% | 2 | 5% |

| Private training organization | 1 | 1% | 1 | 2% |

| SME | 14 | 18% 8 19% | ||

| VSE 41 | 52% | 17 | 41% | |

| Total 79 | 100% | 42 | 100% |

In Table 6.1, the “Corpus of data” column shows the population to be observed, broken down by structure type and the percentage represented by each. In total, the whole network comprises 79 structures, 42 of which make up the sample. The sampling method is similar to that used in the analysis of the innovation environment of the Jura Arc, whose results are based on a survey of a sample of businesses (Pfister and Nemeti 1995, p. 32). The different structures are categorized according to their size and status. From previous studies, the nature of partnerships can be measured by, for example, separating SMEs from large firms (Levy and Talbot 2015), but in order to adapt to the scale of the Genopole network, VSEs or start-ups have been dissociated from SMEs (who do not exceed 60 employees in the area studied). Finally, it should be noted that the intermediation structure does not appear in the list of structures for the network studied. Indeed, by accrediting and supporting laboratories and companies, the intermediation structure is in contact with all the members of the cluster. To include it in the analysis would have led to a star-shaped graphical representation that would have overshadowed the object of our attention: the relations between accredited members1.

While network analysis allows for the mapping of relationships, it is the interviews and observations that allow for their nature to be known. Indeed, the categorization of relationships between cluster members was developed during interviews and observations, which are an essential step in “discovering the nature of structuring social resources likely to be exchanged between actors” (Eloire et al. 2012, p. 81). In the literature, there are a large number of relationship typologies, according to the authors. Economist Nicolas Carayol outlines five types of collaboration (Carayol 2003): (1) a laboratory performs technological service work on behalf of the company (whose financial outlay and risk-taking are low); (2) a bilateral partnership in which industrialists can hire students and postgraduates, and academics can benefit from subsidies as well as targets (businesses) for their research; (3) the investment of large groups in fundamental research, where the potential for technological disruption is considered to be very high; (4) more modest collaborations in terms of scientific and technological potential, but which, nevertheless, allow companies to receive scientific recognition and to develop innovative technologies; (5) the final relationship typology refers to important research consortia in which companies and laboratories benefit from significant public subsidies in order to create research networks with shared results. Perkmann and Walsh reduce the typology to three categories of collaboration (Perkmann and Walsh 2007): research services (industrialists call on researchers and pay them for expertise, technological and/or scientific competence), research partnerships (formal collaborations around research and development activities) and collaborative research, bringing together researchers and industrialists around a common research problem.

As we can see, these different exchanges are not dependent on spatial proximity. Nevertheless, empirical studies agree on the existence of at least partially non-market exchanges between organizations belonging to local systems, which may take the form of exchanges of information, technical assistance, peer support and so on (Grossetti 2004, p. 164). Drawing both on existing categories in the literature on relations between science and industry (Estades et al. 1996; Carayol 2003; Grossetti and Bès 2003; Perkmann and Walsh 2007; Renaud 2015) and adapting to the particularities of the field studied, the study of interactions at Genopole draws up a typology presented in Table 6.2.

Table 6.2. Typology of cluster interactions

| Type of interactions tested | Essential characteristics of the interaction |

| Collaboration contract | Contract that formalizes an agreement between two structures to pool resources and knowledge with shared results. |

| Consortium | Research and innovation project whose financiers (competitiveness cluster in France or principally the EU’s H2020 program) require the association of industrial actors (companies) and scientists (laboratories, research organizations, universities, etc.). |

| Subcontracting | Contract by which one company requests another to carry out a part of its production. |

| Customer-supplier | The sale of a product or process by a supplier to a customer who purchases its goods or service. |

| Cosupervision of thesis | Supervision of a PhD student by two people belonging to two different institutions, between two laboratories or between a laboratory and a company (CIFRE). |

| Assistance relationship | Loan of equipment or technical assistance without commercial exchange. |

6.1.2. Scientific and market relations behind informal interindividual exchanges

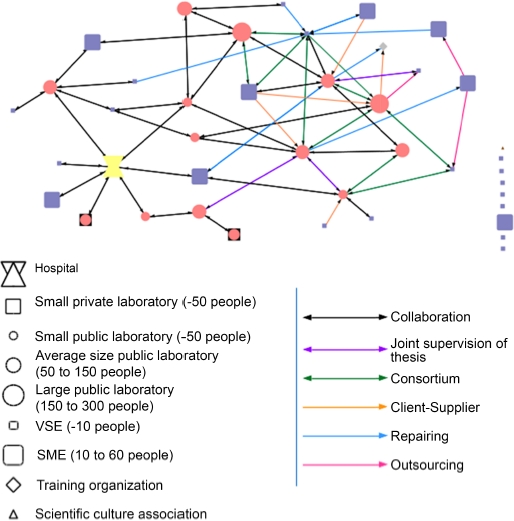

Both the structure typology and the relationship typology have been integrated into the Ucinet software package (see Figure 6.1). Relationships involving reciprocity are illustrated by a double-headed arrow: these are collaborations, consortia and thesis co-directions. For subcontracting, help desk and client–supplier relationships, the arrow indicates the direction of the relationship2. It should also be noted that, in some cases, two network members share more than one type of relationship. In these situations, for the sake of clarity, a hierarchy has been applied that consists of prioritizing the relationships in the following order: collaboration contract, consortium, subcontracting relationship, client–supplier, thesis cosupervision and assistance3.

The interorganizational network thus obtained offers a representation of the tensions that operate in the cluster, while at the same time providing accurate information on the links maintained by some of the members. We can see that collaboration contracts structure most of the exchanges. Laboratories are the most involved in this type of interaction, equally with companies (11 dyads4) and also among themselves (11 dyads). The predominance of laboratories in this type of relationship can be explained by the fact that research is increasingly structured by contracts with other laboratories or businesses that enable it to finance its work or to have access to resources, such as research teams or equipment (Cassier 1996). Relationships between laboratories are not limited to collaboration contracts and we observe that they are also modestly linked by consortiums and thesis codirections. The laboratories are also in relationships with a third type of actor, which was not included in the initial sample: the hospital. In the case of the hospital, its position within several triads can be explained by its ability to make cohorts of patients available to businesses specializing in health for the clinical testing phases.

Figure 6.1. Network between 42 biocluster structures5. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/vallier/clusters.zip

Relationships between industrialists are almost non-existent, mainly due to competition and industrial espionage, which is one of the negative externalities of clusters highlighted in the literature (Torre 2006; Depret and Hamdouch 2009). As for relations between science and industry, we observe that laboratories and companies are relatively linked by the different types of scientific and commercial relations: collaboration, consortium, subcontracting and so on. An additional form of interaction between science and industry, which escapes network analysis, nevertheless emerges: the creation of companies from technologies developed in laboratories. Unlike an exogenous relationship with another cluster member, this is an endogenous process, known in innovation jargon as a “spin-off”. It refers to the carrying forward of an innovation or a scientific process developed within a structure by the creation of a company. 19% of the structures participating in the questionnaire were created by another structure in the cluster and 26% originated from new companies.

Customer–supplier relations appear particularly patchy, given that one of the three externalities of the Marshall district is the emergence of specialized suppliers (Branciard 2002), as well as subcontractors, who form the pillars of the Porterian cluster, along with producers and customers (Leducq and Lusso 2011). The methodological choice of showing “formal” relationships first on the figure is a reminder of the need for graphical clarity. As a result, informal assistance service relationships (loan of equipment, technical assistance, exchange of information without commercial exchange and/or contractualization) are under-represented. In fact, the figure shows eight such relationships (in blue), whereas there are 14 in total. This type of relationship therefore comes second to collaboration contracts.

These assistance relationships observed on an organizational scale were also highlighted in the relationships between individuals working in the cluster. Indeed, 27% declare having helped another individual in the cluster and 19% declare having been helped by another person in the cluster:

At the production level, from the labs, we are starting to know our neighbors better. When we need something, we can go knock on their doors. We still have access to things, but it’s limited to the loan of small equipment (Interview with Emma, accredited company research engineer, July 2015).

Geographical and technological proximity (using the same equipment and facing similar problems) leads to “knocking on neighbors’ doors”, provided that they know them beforehand, as the interview extract above underlines. This spirit of assistance is similar to informal links such as bartering or material exchanges, highlighted by Faulkner and Senker (1994), but does not constitute a perennial reciprocal interaction insofar as “mutual aid and cooperation cannot be confused with a succession of ‘helping hands’” (Alter 2002, p. 269). Interindividual exchanges are therefore convivial6, even friendly7, but rarely convert into professional collaborations. Moreover, most of these links seem to have been forged in the relationships of former students or colleagues, rather than in brief encounters on the cluster. The somewhat outdated and colorful expression “cafeteria effect” (Lipinski 2013), which consists of thinking that, by working in close proximity, individuals with different institutional affiliations end up setting up collaborative projects from their informal meetings around a coffee machine or restaurant table, has its limitations. As Claude Fisher has shown, most individuals meet through structures that are considered stable and enduring (family, work, neighborhood and school), while brief encounters in a bar or restaurant rarely convert into strong ties (Fischer 2011).

On the contrary, the fact of having shared the same studies or the same employer demonstrates a professional circulation within the cluster. Nearly a quarter of respondents (23%) say they have worked in at least two structures in the biocluster. This local job market is particularly encouraged by laboratory directors and company managers who, according to the interviews, form the “little world of genomics”. Here again, the interknowledge of managers appears to be used more to identify and capture skills than to establish collaborations. These collaborations seem to take place more outside the cluster.

6.1.3. More outwardly looking organizations

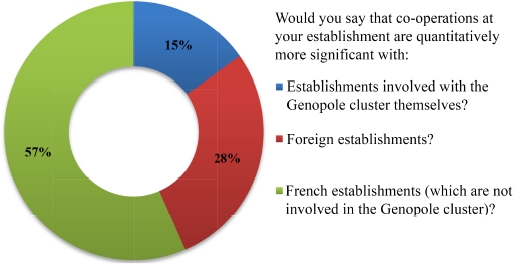

Of the 32 managers questioned, 57% put French institutions not based in Genopole at the top of their list of cooperative ventures, 28% said foreign institutions and 15% said institutions based in the cluster (see Figure 6.2).

Having focused attention in the previous chapters on exchanges at the local level, it is now appropriate to ask the question of the insertion of actors in networks outside the biocluster. The literature (Bathelt et al. 2009) shows the strategic importance of external links (global information pipelines) in the development of a cluster without dense internal networks (“local buzz”). Moreover, the biotechnology market has a strong transnational dimension that has largely developed in the industrialized countries of Western Europe and North America (Foyer 2006). Moreover, biotechnology fits the research and innovation model advocated by the OECD within its member countries. It is therefore not surprising to find that 58% of the sampled organizations’ trade is with Western Europe and the United States8. In the end, several authors question the legitimacy of the local scale, at the expense of national and international relations, as a relevant framework for analyzing innovation activities in an increasingly globalized context (Boschma and Frenken 2009). This point of view is echoed in the population surveyed at Genopole, as in the case of this teacher–researcher:

Is geographical proximity an advantage? Theoretically, yes, but today communication methods have evolved enormously, researchers are used to traveling and finally it’s no easier to collaborate with someone who is 500 meters away than someone who is 500,000 km away (Interview with Emmanuel, teacher-researcher and laboratory platform manager, July 2014).

Figure 6.2. Intra- and extra-cluster organizational relationships (in France and abroad). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/vallier/clusters.zip

The idea contained in this extract, where geographically distant actors may be able to maintain relationships through physical (he mentions the habit of traveling) or virtual (new communication technologies) exchanges, is in line with theoretical findings (Hamdouch and Depret 2009, p. 13). This trend is particularly strong in the biopharmaceutical sector, where links with large national and international industrial groups are sought after (Owen-Smith and Powell 2004), which is corroborated by this comment made by a company director of studies:

In fact, our customers are more big pharma or middle pharma, but internationally, in fact, a little bit nationally but not much. Anticancer molecules is not really their field, either that or they are not advanced enough to be able to do it. We don’t have any clientele here […] and, in terms of collaborations, we do have some, but not here. We do have some with the Curie Institute, with Cochin, with a hospital in Marseilles and in Montpellier […]. The company was created with the Curie Institute and it provides us with tumor models […]. After that, we have collaborations in the United States, but this is more for joint development, at the technical level (Interview with Leïla, accredited company director of studies, July 2015).

In addition to big pharma overseas, this respondent’s company has collaborations with scientific institutes or hospitals, but which are located elsewhere in France. The same observation can be found on a quantitative scale in a 1996 study which reveals that 70% of the formal links between academics and American biotechnology companies are made outside the local framework (Audretsch and Stephan 1996). In a context of geographic clustering of innovation activities, how can we explain that the local level does not appear to be the relevant level?

6.2. Cooperation prevented by paradoxical demands

This second part of the book has repeatedly highlighted the existing tension between the individual logics that run through the organizations and the cluster’s desire for cooperation, which is effectively perceived and experienced by the respondents as taking second place to an already busy job.

6.2.1. Additional time pressure

The different forms of networking all have in common that they mobilize the workers of the site outside of working hours of their company or laboratory. However, their working time, whatever their organization, already seems saturated. Indeed, workers in laboratories are increasingly subject to constraints in terms of workload. For a long time, researchers’ working time has included a diversity of activities between research, teaching and valorization. The so-called administrative activity is also becoming increasingly important, around stewardship and university management tasks (Dahan and Mangematin 2010). These tasks are linked to the 2009 legislation on university autonomy, and also to the logic of calls for projects that require administrative skills (see Chapter 5). Peripheral activities (procedures, reports, minutes, funding applications, etc.) are gradually nibbling away at the researcher’s core business (Hubert and Louvel 2012, p. 22). Faced with this plurality of activities, researchers’ working time is closer to that of the self-employed or the liberal professions (not counting time, evening and weekend work, advancing research during vacations, etc.) than to that of the administrative staff, who support teaching and research activities (Gastaldi and Lanciano-Morandat 2017).

This strong commitment to work is all the more significant because it is internalized as voluntary and mandatory participation from the postgradutate, which constitutes, from this point of view, a long period of socialization, with a “need to work a lot, which ends up being ‘naturalized’ as evidence, a norm, which is then no longer questioned” (ibid., p. 4). With tenured staff, the expected time availability can even be almost 100% among young researchers (Del Río Carral and Fusulie 2013), who see their involvement as a way to stabilize their non-tenured status within laboratories. The “I am overwhelmed” of the teacher–researcher (Aït Ali and Rouch 2013), highlighted in the literature, is accompanied by frequent displacements, linked to the spread of university buildings in the city of Evry. Let us listen to this teacher–researcher in this regard:

We’re still on a very fragmented campus and, as we have classes, we are already walking around quite a bit. We give courses in several buildings in Evry, all at a fairly fast pace. So, when you’ve already gone from one to another… well, there you go, you can’t do everything… (Interview with Blandine, university laboratory director, October 2015).

As we have seen previously, time optimization is also a must in companies that then neglect the network dimension, as this company manager explains:

The problem is that I’m often caught up in a lot of things. When I know in advance, it’s good. We have very time-consuming activities during the day, I have a lot of things to do, I constantly have to talk with the United States, talk with my partners, etc. I don’t have to communicate to promote the company, I have to communicate with my partners. I don’t have any communication to do to make the company known, I have my own internal management to manage, the networking dimension takes a back seat (Interview with Philippe, leader of a company accredited by the biocluster, December 2014).

Whatever their organization, individuals are asked to participate in cluster activities. However, for most of them, this means concentrating on the internal activities of their respective organizations, which represent a significant workload. In this general context of reduced availability, networking creates additional time pressure. The workers agree to make use of their lunch breaks to participate in cluster activities. A consultation carried out on the expectations in terms of cluster animation indeed points out this phenomenon. In anticipation of the opening of the multi-purpose room, L’Escale, a question was asked about the preferred times to use this room. 37% of people declared that they would often or fairly often use the room between 12 noon and 2 pm. However, the short duration of the lunch break (75% of the 534 respondents take between 45 minutes and 1 hour 15 minutes for lunch) defines a greatly reduced availability, even though this is the preferred time slot. The end of the day, on the contrary, is reserved for prolonging work or going home:

Genopole has always had these very commendable efforts to have a campus life. There are picnics, I feel like it’s getting a little bit better, but hey (sighs). Evry is still a town where you don’t stay. There are a lot of people who work here, but who don’t live here, starting with me. I live in Paris itself and, after work, you prefer to go home. At Harvard and Cambridge it’s a little different. This campus life really is something very American. We’ve tried to copy and paste that model here, but it doesn’t work too well… (Interview with Patrick, research institute director, September 2015).

In this case, the desire to go back home is reinforced by the fact that Evry is not a place where people want to stay. In addition, there is recognition of efforts led by the biocluster, but whose copy-paste of the North American model is not appropriate to the local configuration. Here, the observation is far from following Dujarier’s idea that “working with programs implies adopting their rhythm […]. Programs, in fact impose a uniform and universal cadence of their own” (Dujarier 2015, p. 37). With the cluster, we observe a contrario that individuals have no interest in adapting their personal rhythms to that of the “campus life” mentioned in the interview above. This feeling that the biocluster’s strategies are not adapted to the individual and collective practices of the site’s organizations is quite widely shared.

6.2.2. A disembodied objective between prescribed program and real work

The additional time pressure exerted by the cluster produces a strong distortion between the discourses it promotes and employee practices (Linhart 2010). Indeed, the ambition to modernize programs does not radically change organizations overnight. Moreover, the ambition to “get managers at different levels and the employees themselves to sign up to a vision of the world created from scratch” (Linhart 2015, p. 48) cannot be achieved simultaneously and homogeneously. This discrepancy between discourse and practice, and between the practices themselves, produces asynchronous logics. Depending on the hierarchical levels or departments, new programs will not be integrated in the same way or within the same timeframe by individuals:

What I see is that Genopole is developing many tools to help people interact. After that, does it work or not? In my small way, in my field of applied research, I’m still in the decoding phase. So, as a result, we are not necessarily in the same dynamic. Start-up dynamics are based on a goal and a schedule, so we also work with that, but it is perhaps less constrained because we don’t have the commercial side onside. So, of course, we don’t have the same dynamic (Interview with Blandine, university laboratory director, October 2015).

This laboratory director says she is well aware of the “many tools” developed by the biocluster, but, in her opinion, the objective of interaction with a company seems to be disembodied from her fundamental research activity. Moreover, we note the dissonance between scientific and commercial temporality mentioned at the start of this chapter, where the program is known about, but it does not meet with interest. In her book, Dujarier refers to the program designers as “planners”, an appellation which, as well as referring to their function of creating plans, also refers to a characteristic that they often begrudge: that of “planing”, or hovering, over physical work situations. Several of the people interviewed spoke of the secondary aspect of participation in activities in the face of the managerial and financial imperatives to which accredited organizations are subjected:

Genopole cannot hire people to do this work. We need volunteers because, realistically, the money would be better spent elsewhere. Especially those of us in science, we need money every day, we’d rather buy equipment than have Genopole hiring three clowns to do animation… (Interview with Marine, accredited laboratory study engineer, September 2014).

In this extract, the need to be “realistic” from a financial point of view is confined to the recruitment of “three clowns” to ensure the animation of the cluster. Whereas, in Dujarier’s analysis, “planners” accuse opponents of the programs of being “dreamers” (Dujarier 2015, p. 67), we note that here it is the intermediation structure that is blamed for its lack of pragmatism. For this commercial manager, it is important to “talk about sales figures” or “export assistance”. She even feels that the proposals for collaboration show that Genopole has not understood her imperatives. In a few cases, however, some of them have assimilated the concept of streamlined cooperation, taking place in time and space outside the organization. Indeed, during one interview, a company director was even considering making appointments during lunchtime just to “network”:

One of the problems is that everyone has their own life, but this is the same wherever you are. We don’t know many people, but we’re also trying to reach out… From what I see, people are quite willing, but it’s more that: (1) we don’t necessarily take the time to get to know others, and (2) there is little or no group spirit. I don’t know if we should develop some tools and say, once a month, have lunch with someone I don’t know, but who might be of some interest. We don’t take the time and there aren’t necessarily the conditions for us to take the time we want (Interview with Raphaël, accredited company director, September 2015).

However, although this rational conception of cooperation resonates with this entrepreneur, the same is not the case for most of the workers on the site. Indeed, the workers involved with laboratories and companies are aware of the programs put in place by the biocluster, but these appear as a disembodied objective, or even as a contradiction:

For me, first of all, it’s important to be clear about why we want to strengthen links. If it’s just for it to be fun, we can organize soccer games, to give ourselves the illusion that there is a campus life like there might be in the US […]. I’ve got the feeling that we are putting the cart before the horse. Maybe I’m wrong and Genopole has already done an in-depth study on this, but by participating in COSEB meetings, I’m trying to make an effort, to force myself to participate. But I do think it’s putting the cart before the horse to set up these contacts, this activity, without asking: Why? What are we expecting from it? What is the objective? Will something come out of simply putting people in contact? I’m not saying they shouldn’t do it, but they have to ask the question why […]. If you ask companies “what are you interested in at Genopole?”, they will all be politically correct and answer things like “yes, it’s the dynamics”. But, in fact, isn’t it because we gave them some of their money? I mean money, rather than support, infrastructure and mutualization… (Interview with Patrick, research institute director, September 2015).

The above extract concludes with the priority reasons for locating businesses into the cluster, which remain support and shared facilities. Hence, the question of why people should be brought together is of primary importance to this researcher and institute director. Moreover, his phrase “putting the cart before the horse” is indicative of the nonsense seen in literature on the dynamics of geographic concentration. Indeed, in the case of clusters, the concentration of biotechnology activities is seen as a means of creating cohesion. However, this logic runs counter to traditional location strategies, both private and public, which are based on the opposite reasoning, where cohesion is a prerequisite for concentration (Lamy and Le Roux 2017, p. 97).

As we see, the system is far from being as harmonious and coherent as the cluster’s communication claims. Depending on individuals’ social position or sense of belonging, the relational dynamics desired by Genopole are not received and assimilated in the same way. These disparities, and even refusals to cooperate on the part of employees, both within the businesses and laboratories on the site, compromise the implementation of new organizational systems. The expression “putting the cart before the horse”, used by the institute director, illustrates the implementation of an asynchronous organizational model. According to Linhart, this model consists of “changing the employees before changing the work” (Linhart 2010, p. 79). Employees are encouraged to change their behaviors, even though these new behaviors are not appropriate. It is a question, again according to Linhart, of “replacing employees, professionals and bearers of values and potentially conflicting interests with humans who are supposed to share the same issues and are considered as fellow human beings” (Linhart 2015, p. 48). In addition to maladjustment, the demand for like-minded individuals, capable of cooperating, may in fact lead social groups, with conflicting interests, to confront each other. Let us analyze a little more closely what these contradictions are about.

6.2.3. Loyalty and performance objectives towards the employer

Whether in laboratories or in companies, cooperation with external organizations is not a priority requirement for employers (see section 6.1). It may not even be required internally as research teams compete for funding (see Chapter 5). Cluster workers thus find themselves caught in a paradox specific to the hypermodern individual, who is both individualistic and socialized. First encountered in multinationals, this individual now finds himself at the center of contradictory demands across the working world: “on the one hand, responsible and creative, he must also fit into models (being a good learner, a graduate, feeling good, etc.), constraints (competitions, selection, hiring, etc.) and very strict standards” (de Gaulejac and Hanique 2015, p. 12). The paradox is mainly to be found in the institutional demand for a team mentality, in the company or the laboratory, while within them work is evaluated by individual performance, whether it be academic standards (publications, patents, etc.) or merit-based advancement (individual interviews, personal development, etc.).

The work organizations observed in the context of the survey all advocate values of competition, performance and personal achievement, while the cluster expects better interorganizational cohesion. The management of the biocluster is astonished by the disappearance of worker collectives, while modern management is constantly promoting individualization and rivalry. From this, we observe a dual paradoxical conflict between the contradiction between individualization and cooperation, which seems to go hand in hand with a competition paradox (encouraged by the accredited organizations), and cooperation (desired by the public intermediation structure). Indeed, Genopole reinforces this paradoxical process by demanding cohesion and cooperation from work organizations that celebrate competition and individual performance, as Castel, Hénaut and Marchal have pointed out:

In many sectors, actors face potentially contradictory demands, with, on the one hand, incentives to perform better economically or scientifically (“be the best!”), and, on the other, demands to be more collaborative (“cooperate, share information!”) (Castel et al. 2016, p. 10).

As we have seen, however, cooperation and information sharing are not promoted within laboratories and companies. Although the logic of cooperation was dominant before the creation of Genopole within the international “Human Genome” project, the logic of competition is now the order of the day:

Fifteen years ago, the Human Genome Project was an international collaboration, the sequencing technologies were in such a state that everyone had to work together to produce a result, all the data was shared, everyone was assigned a role, there was true international cooperation. Now, the evolution of sequencing techniques means that we have moved to an international competition, where everyone has the capacity to generate massive data, increasingly private databases that are not shared with others. There is still shared data, but we have changed the model to a competition for access to data with large private players like Google, which is getting into the game to control the data and information (Interview with Patrick, research institute director, September 2015).

We can see it here: data sharing is no longer appropriate today, especially in a context of private owners such as Google, quoted in the above extract. Cluster organizations are faced with industrial giants that accumulate, protect and privatize their data. In this context, as we have seen, whether they work in laboratories or in companies, individuals in the cluster are subject to confidentiality requirements: disclosure forms, Confidential Document Agreements (CDA) for laboratories and confidentiality clauses in company contracts.

Moreover, when accredited organizations interact with other actors, they are not necessarily located nearby. An organization cooperates all the more with actors located outside the cluster when it is specialized in a particular field and therefore needs to look “elsewhere” for knowledge, skills or resources (Hussler and Ronde 2005). The following comments illustrate this:

At the biocluster level, I have never set up any collaboration agreements, except for small contracts to use instruments in labs or in other biotechs. On the other hand, I have easily set up 30 to 40 in Europe, the United States, Canada, Brazil, Indonesia, China, Holland, Italy… […] The activities of Genopole’s labs and biotechs were not useful to my development program and, as a result, I did not set up any. If there had been anyone of interest to me at Genopole, I would obviously have contacted them […]. I never made use of this proximity, because the activities of either biotechs or academics were either not useful or I had not identified them… I don’t know, because at some point, when we have a need, we identify the best, based on their patents or their publications, and those who are not identifiable, well, we squeeze them out, even if they are three blocks from us (Interview with Alexandre, director of a company accredited by the biocluster, September 2015).

This business leader sheds light on the priority given to collaboration with the best in a field, based on its patents or publications, rather than based on proximity. The performance of the organization takes precedence over local cooperation. Thus, the central role of cooperation in production models, such as that of the cluster, appears to be difficult to reconcile with the individualism and competition advocated in the accredited organizations. On one side, employees are encouraged to take initiatives, to leave their organization to exchange information. On the other side, they are subject to strict standards, in terms of schedules and confidentiality, and to processes of accountability and performance with regard to their respective organizations. Finally, the legal rules of capitalism, such as private property, confidentiality and competition, and the organizational rules linked to hierarchy or modern management produce individual logics of subordination to the organization, which contradict the aims of the cluster, who would like social production to be more shared. However, cooperation is ultimately prevented by the dominant capitalist logic in the accredited organizations.

6.3. Avoidance strategies

While the raison d’être of clusters is their function of geographically grouping and connecting people, in reality their programs produce avoidance of cooperation.

6.3.1. Avoiding scientific and technological issues

The contradictory demands to withdraw and cooperate places individuals in delicate positions where they have to be careful about what they say and judge how much they can talk with their interlocutor:

Company A doesn’t have that confidentiality issue for example, they’re into commercialization. They are no longer in the development phase of new technologies, so they are freer, they can talk more. On the other hand, Company B is more closed, we don’t talk about professional things. With a colleague from the same company, we can talk about all this, because he is subject to the same secrecy as we are, and that feels good (Interview with Rizlaine, biomechanics engineer in a company accredited by the biocluster, December 2014).

In this extract, we can see the discomfort of concealing company-related information and the relief of being able to confide in a colleague. Above all, the secrecy places them in an indelicate position. Employees who are no longer bound by this confidentiality are considered “freer” insofar as they can speak. Thus, the construction of a mobilizing collective and a community of values, which is based on a juxtaposition of organizations and individuals maintained in a spirit of competition (de Gaulejac and Hanique 2015, p. 180), can have psychological consequences for already highly pressured individuals, as economic literature has also identified:

The obligation to cooperate without the subjective conditions of this cooperation, in other words, adherence to rules and values shared in a community mode, cannot fail to have significant long-term effects. The rise in stress in the workplace, at the same time as collective reference points are disappearing and threats to employment are increasing, is weighing on the psyche of employees. The ersatz collectives represented by participation programs and company projects do not succeed in filling this void (Coutrot 1998, pp. 245–246).

Placing individuals under a constraint to cooperate, without their having the means to do so, can lead to stress and even to behaviors that are antinomic and counterproductive to the cluster’s objective. During the survey, particularly during the “Site Life” and “Animation” projects, phenomena of avoidance of scientific and industrial issues were repeatedly observed. The program, one of whose objectives was to create working communities within the cluster, has often failed for this reason. We have seen this with the PhD students club, where students were forced not to reveal their thesis results by the policy of their host laboratory, which consequently fell back on organizing “professional life after thesis” meetings. The same was true of a meeting on the formation of an entrepreneurs club. A manager who had just started his business expressed this reluctance:

I’m a bit reserved about tackling technological issues because it will be complicated. It will, out of necessity, limit the discussion. For reasons of confidentiality, I wouldn’t feel free to speak… On the other hand, on questions of management, of attracting investors, that’s common… But on questions of research, that’s different (Extract from a meeting where the agenda was the creation of an entrepreneurs club, April 20, 2017).

In the above extract, we again note the feeling of not being free to talk on science and technology issues and the preference to avoid such topics. The 11 business leaders present at this meeting were unanimous on this point. On the contrary, they did not agree on the content of the meetings. Some wished, in a very pragmatic spirit, to address issues specific to business leaders, such as management, participation in international trade shows and finding investors, while others preferred to focus on convivial meetings (restaurants, aperitifs on a barge) that would generate confidence:

I defend the idea that the priority is for us to create a link between us, so that we know who to turn to if we need information… For me, trust is important, so there is a balance to be found between productivity and conviviality in this group. But the priority remains conviviality, not in the social sense, but in the sense of creating a link (Extract from a meeting where the agenda was the creation of an entrepreneur’s club, April 20, 2017).

The productivity aspect of the meetings is not hidden by this entrepreneur, but the creation of a bond of trust between them comes to the fore. For Simmel, social life would not be possible without “affective elements”, particularly benevolence and trust (Watier 2009). This is even considered by some as a prerequisite for economic exchange (Dasgupta 2011). The extract above suggests that it would be absent from exchanges between entrepreneurs and that it would be appropriate to “create a link”. Nevertheless, it remains a protean notion that does not function in a binary way (“I do or don’t trust”). We can count on the benevolence of a person, without necessarily trusting them to solve a given problem (Grossetti 2009). Indeed, during one interview, a teacher–researcher explained the difficulty of talking with a colleague from another laboratory or company, even to seek help, insofar as:

Even if I know them well, it’s tricky… If you start explaining your problems, you start talking about your methods, it quickly becomes complicated… (Interview with Gerard, accredited laboratory teacher–researcher, May 2014).

As we can see, even though the interknowledge exists, the climate of trust is lacking. This context lead the 11 participants in the entrepreneurs club meeting to unanimously agree that scientific and technological subjects should be avoided, despite the intention to create forms of mutual aid between leaders. Whether between PhD students or between entrepreneurs, to take only these two examples, resistance was very present. Everything happened as if the core production activities of companies and laboratories could not be discussed, as if it were untouchable. This phenomenon was noted at the very beginning of the survey, through the consultation carried out for Genopole. One question asked about the types of activities biocluster members would like to have access to in the multi-purpose hall, which has since become L’Escale. Only 12% of the 534 people questioned for this consultation wanted to practice any scientific type of activity there. As we can see, the convivial dimension seems to be the part of the program that works best. Indeed, in addition to access to attractive leisure services, the opening of a sports and cultural activity hall seems to be one of the rare spaces where “business” or “science” is not discussed, except by chance in the course of a conversation. Everything happens as if sociability becomes possible, as soon as scientific and/or industrial considerations are avoided.

6.3.2. Cluster administrators: between belief and lucidity

The resistances observed above are considered by a section of French economic literature to be the unfulfilled promises of cluster policies, notably their low profitability, which does not seem to amortize the costs of the program, and the lack of correlation between spatial concentration and industrial and scientific performance (Duranton et al. 2010). At an individual level, frustration and guilt can form among workers who fail to participate, to cooperate with the rest of the cluster, as they strive to perform their jobs (de Gaulejac and Hanique 2015, p. 28). This guilt-tripping is all the stronger with the administrators who set up these programs and find themselves caught in the crossfire, from, on the one hand, management that expects them to produce synergies and, on the other hand, a lack of participation by individuals evolving in the accredited organizations. Indeed, faced with the failure of their mission, these workers must assume the disappointment of their management:

I am a little disappointed […] after the excitement where there were quite a few things put in place, we see that the audiences are getting smaller and smaller. I find that a problem… When we did the first “gene cafés” in the 2000s, it was interesting. There were 250 people, but then 100 and we ended up with 10 or 12. Was it because of the speakers? Yet we were paying attention. I never understood… I think there is an element of idea fatigue. But the very idea of animation and Site Life is to be able to renew activity, even if it means going back to the original ideas. It seems to me that there is a need for renewal that is not done enough (Interview with biocluster management, April 2017).

In this interview extract, we note the process of renewal of the programs, since the 2000s, which initially aroused enthusiasm and then suffered from a lack of participation, creating disappointment among the administrators. This difficulty for the “Administrative” and “Site Life” teams in encouraging participation among cluster members was observed at close quarters in the context of the CIFRE. The findings of the survey on the structural dysfunction of the facility over the past 15 years were also shared with the teams. They were relieved to understand that the problem did not come from their work per se. Like Dujarier’s “planners”, they were not fooled and they too noted the discrepancy between the promises of the plan they had drawn up and the reality on the ground. In spite of the disappointment observed among the managers, we also observe phenomena of lucidity with regard to the programs put in place:

The first level is: do I believe in partnership policy as a component of innovation development? The answer is “No”. It allows people to get to know each other and develop joint research […] And, in fact, when you look at the economic and industrial results of all this, there is not much to show for the money we put in. On the lab side, the lab says “what I am interested in is having a nice publication”, the industrialist says “it is the patent that I am interested in”. But he doesn’t always take the patent, because it’s not necessarily part of the company strategy. When you launch a project, it has to be a project you care about, but, after three years, your strategy may have changed completely […]. In this way, the partnership policy does not seem convincing to me. Secondly, money: if you want to set up calls for projects, you need significant resources and here, again, you need to find funding. The only thing I believe in is Grant Services, not as a funding organization, but as an organization that allows you to find outside funding, although not us directly… (Interview with biocluster management, April 2017).

This extract highlights several aspects. First, the administrators of the cluster believe that the partnership policy has limited effects in terms of economic spin-offs, insofar as they note the different interests of laboratories and businesses. Moreover, the above statement underlines the awareness that, without a call for projects that mobilizes actors in a funding logic, it is very difficult to set up partnerships. Thus, we observe a form of lucidity on the limited effects of the cooperation mechanism. However, this lucidity does not go hand in hand with a belief in the dominant discourse. Indeed, the field study allowed us to observe that all the staff of the intermediation structure oscillated between belief in the cluster effect and lucidity regarding the difficulties they encounter on a daily basis, between, on the one hand, the sugar-coating of communication (see Chapter 3) and, on the other hand, the awareness of the program’s limitations. In so doing, they are constrained, and also want to believe in it. This belief, linked to the cluster’s imaginary, is indispensable to the cluster’s administrators in order to find meaning to their activity.

Although the networking program has been formalized since the 2010s, Genopole has been trying to increase synergies since its inception, as we have seen throughout this book. The renewal of the same process, albeit applied to different audiences (bringing together managers, immunology specialists and PhD students), is part of an unconscious practice of masking the obstacles to cooperation. Indeed, in order to fit in with the dominant discourse, that of the knowledge-based economy and harmonious interactions between science and industry, administrators must produce their own ad hoc rhetoric and put in place mechanisms that respond to these representations. Thus, the difficulties in putting them in place are identified, but mitigated by belief, and the need to believe, in this imaginary of clustering. This belief allows the program to constantly renew, and also to provide these administrators with a meaning to their work.

- 1 The data from the questionnaire show that only one manager declares that he has not had any dealings with the intermediation structure since his appointment. On the contrary, this is not the case for the other managers, 25 of whom even state that they have been in contact with the general management of the biocluster. In addition, the intermediation structure is in contact with the structure group as a meta-organization and resource actor (economic support, fundraising, communication, research support, pooling and supply of equipment, etc.), which does not correspond to the relations exchanged in the rest of the cluster.

- 2 In the graph, the direction of the arrow from X to Y indicates that X subcontracts to Y, that Y is X’s supplier, or that X troubleshoots Y.

- 3 Without going back over Porter’s definition in detail, the concern of clusters is to develop formal collaborations, whether commercial and/or scientific, in the innovation process. Thus, contractual relationships appear as a priority, before tacit exchanges. As a result, troubleshooting relationships are much more important than they appear in Figure 6.1.

- 4 Dyad: link between two actors of the network.

- 5 For a more detailed analysis, see Vallier, E. (2018). A journey in cluster: what about its relational promise? ARCS – Analyse de Réseaux pour les Sciences Sociales (Social Sciences Network Analysis), GDR Analyse de réseaux en SHS (Human and Social Science Network Analysis Research Group).

- 6 55% of respondents report having developed friendly relationships with people from cluster institutions.

- 7 Of the individuals surveyed, 23% admit to having friendships across the cluster.

- 8 In fact, in the questionnaire, while company managers and laboratory directors answered that their relations with foreign countries were quantitatively more important, the questionnaire was designed to ask them about the geographical area of these international exchanges.