4

Can Coordination in Extreme Environments be Learned? A Managerial Approach

Adopting a practical approach in order to analyze team coordination in extreme environments opens up promising research. It offers the chance to discover the “implicit” side of the phenomenon, by examining the players’ actions under the pressure of the changes, uncertainties and risks they are exposed to. Furthermore, viewing team coordination as a set of practices emerging in situ makes it a phenomenon, which is, in principle, difficult to implement. Coordination is thus no longer predetermined; it is shaped during action, in the continuous construction of the players’ practices and ways.

Under these circumstances, adopting a practical approach to understand the coordination as it is “being made” involves thinking about its implementation differently. It leads to the search for answers to the two following questions: can coordination in extreme environments be learned? And what roles can the managers play in order to guide and support their teams in the development of their coordination?

The different case studies presented here describe an emerging coordination, closely tied to the players and their context: team coordination results from a process of experimentation, which makes sense through the players’ past and present actions.

For this reason, the knowledge and expertise that the team and its members possess, the way in which they utilize and circulate them and the part the organization plays in encouraging these approaches stand out as interesting entry points for conceiving the managerial action.

Thus, it is not simply a question of tackling the research of the operational and managerial dimension in terms of hierarchically-imposed directives; it involves further identifying what Orlikowski defines as enabling conditions [ORL 02], which are likely to support and sustain the development of coordination in extreme environments. The manager in this case plays the role of a facilitator for the collective action, which involves a firm understanding on his part of field practices developed by the players.

This final chapter examines first the knowledge and skills that teams develop in order to coordinate themselves in extreme environments. It continues by proposing managerial avenues and methods aiming to encourage its acquisition: putting in place an immediate feedback system, encouraging the emergence of professional communities and exploiting the benefits of decision support systems (DSS).

4.1. Necessary individual and collective skills for coordination in an extreme environment

How do teams manage to build and rebuild meaning, to decide and act collectively, even though they regularly question the relevance of their own guidelines in handling the switch between routine and unexpected situations? What are the knowledge and skills they exploit in order to coordinate themselves in extreme environments? This questioning helps first in identifying the skills developed by the teams when they develop coordination in extreme environments.

4.1.1. From theoretical to practical knowledge: practices, knowledge and skills

The practical approach fosters a deep interest in how we develop knowledge and its emergence: it is at the heart of a number of works based on this approach (for example, [GHE 99, ORL 02, GHE 06, TSO 01, TSO 05, YAN 09]). It offers a substantially different understanding, however, of the knowledge put forward in a number of now classic contributions known as knowledge management.

McInerney and Day [MCI 07] distinguish between the two schools of thought when talking about knowledge as an artifact on the one hand, and knowledge as a process on the other hand. The former refers to the classic knowledge management literature. The key contributions by Nonaka [NON 94], Nonaka and Takeuchi [NON 95] and Nonaka et al. [NON 08] structure this research stream by focusing on the organizational aspect of knowledge and the importance of modeling the dynamics of knowledge creation.

For example, the socialization, externalization, combination, internalization (SECI) model demonstrates that knowledge is progressively created from the combination of implicit and explicit knowledge. As specified by the authors, the creation of knowledge rests on the interaction between implicit and explicit knowledge through a continuous back-and-forth movement between objective and subjective [NON 08]. McInerney and Day [MCI 07] refer to knowledge as an artifact to the extent where knowledge is approached as a resource needing to be managed. Models and tools are developed in order to create, obtain, diffuse and transform it. Gherardi [GHE 99] talks about “learning in the face of problems”: when faced with an anticipated and clearly-defined problem, the teams create new knowledge tailored to answer the problem. Knowledge is seen as a resource in the service of the process of problem-solving.

The second point introduced by McInerney and Day [MCI 07] is that of knowledge as a process. It focuses on describing the process of the creation of knowledge, more than that of knowledge objects and their use in an organization. In opposition to this first approach, Gherardi talks about “learning in the face of mystery” [GHE 99]. Evolving in an uncertain environment, the organizations, and the teams that comprise them, form part of a constant approach to preparing and anticipating unforeseen and future problems. Knowledge cannot and must not be spread in a predetermined direction; it contributes daily to the collective abilities to adapt and solve problem: “Knowledge is both social and material. It is always unstable and precarious, located in time and space (local knowledge), embedded in practices and dis-embedded (theoretical knowledge)” [GHE 99].

As a process, knowledge must be created in the act; it is closely connected to the actors’ concrete daily practices.

Orlikowski [ORL 02] supports the idea of the inseparability between knowledge and practice, favoring the term “knowing” to “knowledge”: it is a question of emphasizing that knowledge implies the actors’ commitment to action. As outlined by Schön [SCH 93], “our knowing is in our action”.

In this respect, the practices and technological applications refer both to the “knowing”, and to the ability to put this knowing into action, as skills. “Intrinsically connected to ‘doing’” [JAR 07] and to the actors’ “ways of doing”, the practices refer to the question of the implementation of knowledge in any situation. Adopting a practical approach in order to analyze coordination in extreme environments thus raises the question of the obtainment of individual and collective knowledge necessary to manage the switch between routine and unexpected situations.

4.1.2. Skills needed for coordination in extreme environments: the example of tactical airlifter crews

The following case study is taken from an applied study to the benefit of the staff of the French Air Force [BAR 10a, BAR 10b]. It primarily allowed the examination of the individual and collective skills developed by the crew in order to coordinate with each other in extreme environments. In the following, we focus on the Transall C-160 crews, which is one of the most famous tactical transportation aircraft in the French Air Force.

4.1.2.1. Tactical transportation missions and crew

The collective aspect of the transportation professions is crucial to the fulfillment of the different types of missions that are carried out. The crew members refer to a crew “synergy”: every member possesses specific skills, all the while sharing a common language, common knowledge and common values. The transportation crew thus capitalizes on the individuals’ technical and human skills and expertise, while developing a collective skill set (the “synergy”, which is highly valued by the crew).

The missions they accomplish directly condition the nature and diversity of the Transall flight crews’ skills. These can be of essentially two different types, and can be accomplished during the same trip:

- – Logistical missions concern the transportation of materials or men to and from sites where risk is insignificant. The preparation of logistical missions is linked to the optimization of the load (freight or staff) relative to the airlift’s capacity and to the traveling distance. It is a question of seeking a balance between the fuel charge, the airlift’s load capacity, the traveling distance, the mission’s duration, the aviation regulations and the load’s composition standards.

- – Tactical missions are based primarily on the crew’s ability to handle the unexpected. They concern the transportation of materials or men to and from hostile sites. The flight profile’s creation is an important part of any tactical mission’s preparation, and is determined by the risks involved (ground-to-air and air-to-air). Tactical missions are at the heart of the C160 Transall flight crews’ career.

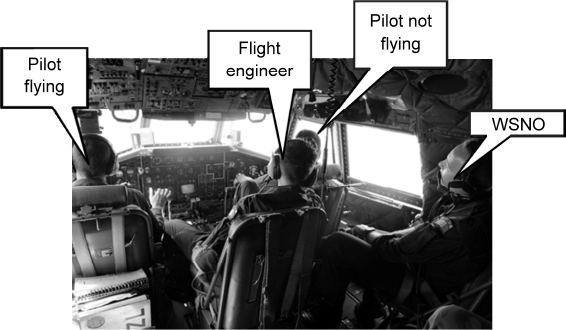

A Transall aircraft’s crew consists of four individuals, each possessing areas of expertise in a particular area of specialty (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1. Crew on a Transall C-160 type aircraft (source: www.defense.gouv.fr)

The crew is made up of two pilots, one weapons system navigational officer (WSNO) specializing in navigation and the use of the defensive aid system (both of which are fundamental tasks during the tactical stages of the mission) and other a flight engineer specializing in the mechanics of the aircraft.

The four crew members complement each other with respect to the tasks that need to be carried out and the manner in which they apprehend events, particularly in temporal terms (the pilots focusing mainly on the short term and the navigational officer more on the mid and long term). The crew’s work, therefore, rests on a combination of skills’ both specialized and shared, distributed collaboratively. Transportation missions require good management of the interdependencies between each member’s area of specialty and a good coordination of each of their action and responsibility areas.

4.1.2.2. Transportation crews’ individual skills: technical, relational and situational

What is the nature and quality of the knowledge and skills developed by crews in their continuous search for coordination? The observation of the practices of coordination in real situations (that is during real flights) and a number of interviews with navigational personnel have allowed us to distinguish three different categories of individual skills [BAR 10b] held by each member of the Air Force’s Transall transportation crews (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1. Classification of individual coordination skills for members of a Transall C-160 crew

Technical skills Expertise relating to embedded systems and the aircraft’s use |

Relational skills Expertise in relating with other crew members |

Situational skills Expertise in adapting and deciding in an operational environment (knowing what to do) |

|

| Pilot flying – left side | Piloting Mastery of the standardized language (actions check-lists) Mastery of crew communication (code words, actions checklists) |

Knowing how to be autonomous, while integrating oneself into the crew and team work |

Taking initiatives – being a source of proposals |

| Navigational engineer | Operating the aircraft: a very fine understanding of the aircraft’s mechanics and machine management Detecting and managing in-flight failures Knowing how to devise a mechanical review Check-lists’ mastery |

Orienting the work of the engineers on the ground Managing the relationships with engineers on the ground Being the intermediary between the cockpit and the hold mechanic Acting as technical advisor to the aircraft commander |

Taking a critical approach to the situation: detachment from the piloting tasks and the weapons system management – technical and mechanical detachment Knowing how to detect problems and propose/discuss a solution (technical advisor to the aircraft commander) |

| Pilot not flying – right side | Managing radio communication Knowledge of entering air traffic Mastery of the standardized language (actions check-lists) Mastery of crew communication (code words, actions checklists) |

Sharing his experience with the pilot flying and the rest of the crew Participating in team dialogue |

Taking a critical approach to the situation: detachment from the piloting tasks – developing a big picture view Offering the aircraft commander alternatives |

| Weapons System Navigational Officer (WSNO) | Navigation management (for example: regulation knowledge, ability to work with maps) Weapons system management (for example: defensive aid system) Threat management Mastery the standardized language (actions checklists) |

Interacting with the flying pilot, mainly articulating short- and mid-term actions during flight (for example: reminding the pilot of the mission’s tempo, objectives and its progress in the mid- to long-term) | Choosing and applying tactics adapted for the context of the action Knowing to anticipate (time management) Taking a critical approach to the situation, detachment from the piloting tasks |

| Mastery of crew communication (code words, actions checklists) | Participating in team dialogue | Offering the aircraft commander alternatives | |

| Aircraft commander (pilot not flying or WSNO) | Managing the mission’s technical and logistical aspects (preparation and conduct) Managing the mission on a broad plan Coordinating the “client’s” needs according to the aircraft’s technical capacities |

Knowing how to create, nurture and restore the crew’s synergy and mutual trust Managing stress within the crew – knowing how to manage concerns and stress Showing empathy Ability to take decisions Ability to delegate efficiently Leadership: ability to secure his or her team’s support – commanding respect Hearing and taking criticism into account Knowing how to work with joint task forces as well as internationally |

Taking a critical approach to unforeseen situations Ability to take a final decision relating to the necessary action(s) Knowing how to cope and find a solution – adapting to the action Adapting to different military and/or national cultures |

The technical, relational and situational skills rest on solid knowledge. They are acquired and perfected through experience, from a process of learning through action, interaction (learning through “doing”) and by trial and error. Beyond its military application, this classification can be thought of in the following way:

- – First, the players develop “technical” skills. These relate to a “know-how” specific to an area of expertise and the use of resources and technologies for said area. They constitute the core of the activity. The knowledge of rules, procedures and action–reaction sequences (behaviors) that frame the activities represents, for instance, the necessary technical skills leading to the good coordination of activities and men. The actors appropriate these skills and internalize them throughout their experiences. They become automatisms, allowing them to efficiently manage routine situations and save time, which will then be used for other urgent tasks during unforeseen situations.

- – Subsequently, the relational skills [PER 02] or savoir-être, appear as key. They are articulated through the management of social interactions and the actors’ ability to integrate the others’ needs and demands relating to the decision process. In this respect, relational skills are linked to the individual’s emotional and social skills [RIG 07]. The former enable the management of emotionalism and stress related to unexpected situations. In particular, they enable the management of body language, of knowing how to send (encode) non-verbal messages, as well as receive them (decode). As for the latter, social skills are mainly directed toward the individuals’ ability to communicate verbally with others, to relate a situation (sequence, respect the order of events and give it meaning) in a suitable way in the eyes of the interlocutor.

It is also a question of knowing how to listen to others and encouraging discussion. Relational skills, therefore, appeal to the crew members’ social intelligence, their knowledge of social conventions and their ability to build relationships based on trust.

- – Finally, favoring adaptation during action, situational skills or “knowing what to do” (or “savoir quoi faire”) translate an individual’s ability to adapt to the demands and constraints of the environment in order to make appropriate decisions.

They refer to managing the switch between routine and unexpected situations, resting primarily on the actor’s ability to analyze information, interpret the situation, managing ambiguity and quickly finding solutions to apply to a situation which has upset the initial plans as a whole. This type of skill refers to the understanding of the action’s context and logic, to intuition and common sense. Situational skills also refer to the crew members’ reflexive skills [COL 06, TSO 05, YAN 09], that is their ability to think about their actions retrospectively (taking a step back) in order for the elements of the action that have not yet been uncovered to emerge and adapt, and evolve their behavior accordingly. In this respect, reflexive skills are the foundation for the practices bearing the same name that crews develop during debriefing sessions (as seen in Chapter 3).

In extreme environments, the actors’ ability to coordinate themselves rests on a sequence of know-how, savoir-être and knowing what to do, that they weigh in relation to the management of situations they must face and the aims they pursue.

For instance, in the case of the coordination between fighter pilots and Special Forces in Afghanistan, described in the Chapters 1 and 3, the procedures, standard modes of communication (code words) and other automatisms acquire a key significance when crews manage routine situations. These coordination elements are principally exploited – acted upon – from technical know-how internalized by the actors during their training and operational experience. When an unforeseen situation arises, frequently provoking surprise and necessitating an adjustment to usual baselines, the savoir-faire becomes background to social skills and knowing what to do.

The actors communicate in order to give meaning to the new situation that they are experiencing: they talk about what they are going through, debate and agree on a solution in order to coordinate themselves. By doing so, they rely on their relational skills, in order to be as critical and open in the discussion as possible, and about their “savoir quoi faire”: what decision to take? How to achieve the objectives when the initial plans are no longer adapted to them? What analogies can they make with previous experiences?

The team mates also employ their technical, relational and situational skills when interacting with technology, revealing uses that were not initially conceptualized by the maker. The case of text-chat, used by NATO military teams in Afghanistan (as seen in Chapter 3), can be seen in terms of skills. Indeed, the virtuous effects associated with combinatory uses can only be fully effective if the players are capable of engaging in multiple opportunities for vertical/horizontal and individual/collective communication. In this context, the users’ technical skills, namely their mastery of the system’s properties, are insufficient. They must know how to communicate with the teams scattered around the mission area, as well as knowing how to best exploit the information they have gathered in order to make the relevant decisions.

4.1.2.3. Collective skills and intelligence in tactical transportation crews

Technical, relational and situational skills are only fully developed within a collective: the coordination within the teams in extreme environments rests on a prominently collective aspect, which cannot be reduced to the simple combination of individual skills.

Collective skills can be defined as the “set of the participants’ individual skills in addition to an indefinable component, specific to the group, stemming from its own synergy and dynamics” [DEJ 98]. Representing certain “shared and complementary knowledge and implicit savoir-faire (…) that participate in a collective’s repeated and accepted ability to produce common results or co-construct solutions” [MIC 05], the collective skills provide teams with a greater capacity to solve problems that they would not be able to treat individually [WIT 00]. They are, by nature, established, namely tied to a context and anchored within a collective. Thus, if collective skills do not exist without individual skills, the former transcend the latter and participate in the team’s performance [RET 09]. The notion of collective skills poses the question of a recursive relationship between the individual and the collective inside the learning loop, as well as that of social (relational, cultural, social identification, etc.), cognitive [RET 05] and sensory processes implemented during their development.

Furthermore, the extreme nature of the environment puts the collective at the heart of the coordination, highlighting the crucial role played by synergy and mutual trust specific to the team and essential for suitable decision making. The ability to solve a problem and coordinate actions in a diffused work environment calls for a minimal versatility on the part of the team’s members. This versatility favors the self-control of actions undertaken by others (pledge of security) and calls for a certain number of shared operational models and common values.

With the Transall C-160 experts, the crew’s composition and the distribution of skills within the crew play an essential role in coordination [BAR 10b]. These two aspects touch upon the determining factors of collective skills development. Furthermore, a crew’s collective skills involve a multicultural aspect that is all at once interdepartmental, international and interarmy. The ability to work with other armies and other organizations (for example, non-governmental organizations), or even with other countries, constitutes a skill in its own right. Finally, the collective skills that emerge from the complementarity and synergy of individual knowledge distributed within the crew involve the implementation of appropriate methods and processes and are notably different from individual-learning methods. The crew members receive a common theoretical and practical education that allows them to develop a shared knowledge. They also belong to squadrons marked by common work values and traditions that transcend the individual aspects in order to cultivate the “collective meaning” and synergy. This common knowledge base is considered to be a prerequisite for crew work, as outlined when interviewing the members that comprise it.

Individual and collective skills therefore allow the teams to coordinate with each other in extreme environments: they acquire the technical, relational and situational savoir faire, as well as the essential component the Air Force teams refer to as “synergy”, that collective skill that allows them to work together, in the same direction. The management of the sudden switches between routine and unexpected situations is determined by the teams’ ability to distribute individual skills, and to then exploit them “together”, in order to find solutions and take the decisions best suited to the events at hand.

The question of the notion of skills operationalization, mainly the notion of collective skills, thus comes forward: how can the manager, and, more generally, the organization act? What conditions can managers implement in order to favor the acquisition of individual and collective skills necessary to coordination in extreme environments? How to encourage the team members to get involved in collaborative work?

Such a questioning points us back to the questions raised by the collective intelligence literature (for example, [ZAR 06, OLF 07, LEN 09]). Collective intelligence represents a tool that allows the development of emulation, adaptability and creativity within a team, in order to guarantee the implementation of its decisions [ZAR 06]. The following sections will describe three avenues for managerial action, aiming to generate and sustain this so-called collective intelligence within the teams: the first two (feedback and professional community) have an impact on the process of learning and the creation of collective knowledge, and the third avenue examines the effect of information systems and the technologies that comprise them (DSS) on the teams’ creativity and adaptability.

4.2. Setting up a process of “immediate” feedback: the case of the Air Force’s Aerobatic Team

The process of feedback consists of “using the development of a real event as an opportunity to collect the individual experience of various players and gather it in the form of a collective experience. [It…] must allow us to capture the representation of the situations’ dynamics in order to better understand past accidents and encourage the sharing of the acquired experience” [WYB 01]. This definition places an emphasis on the two consecutive stages when approaching the process of feedback: it is first necessary to identify the “real event” from which the players will then manage to construct a collective experience. The event is generally an incident or accident (or even a major catastrophe), which significantly disrupted the normal functioning of the organization. The teams can thus learn from the multitude of methodologies and existing feedback processes, describing the process of experience collection and analysis. Frequently elaborated from the perspective of technical and quantitative engineer sciences, they lead organizations to implement new rules and operating procedures in order to avoid the accident from ever repeating itself. Despite the effects of inertia often associated with the different structures involved in the analysis of experience, this first stage seems to be well controlled by teams nowadays.

The second stage concerns the capitalization on and sharing of individual experience in order to favor its distribution at the work collective level. It rests largely upon qualitative approaches, looking to integrate human and organizational aspects in the management of accidents inside the learning loop. In most cases, however, the teams, prompted by the organization, limit themselves to simply creating a database aiming to codify and capitalize on their experiences in order to then support the decision-making process. Despite this, the “codifying everything” approach is often poorly suited to the experiential nature of the knowledge gathered, in the sense that the actors then do not have access to its procedural and contextual dimensions [BES 98, GRI 06]. A subpar use of this type of tool is often observed, as the gathered knowledge rapidly becomes obsolete.

In this context, the appropriation of individual experiences by the collective is, if not nonexistent, at the very least insufficient to produce a “dynamic representation of the situations” and develop the collective experience and intelligence referred to by Wybo and his co-authors in their definition [WYB 01].

This limitation can seemingly be exceeded if the second stage of the feedback process is tackled not as a simple capitalization on experience but as an opportunity to develop the necessary collective skills for coordination in extreme environments.

The feedback process thus becomes a tool in the service of the teams: it encourages collective intelligence while acting upon the communication, reflexive and socialization practices.

4.2.1. “Immediate” feedback processes within the Air Force’s Aerobatic Team

In the last 15 years, a growing number of authors (for example, [BAI 99, DAR 05, RON 06, VAS 07, BRO 09, MEL 11, GOD 12a]) have taken an interest in a particular form of feedback, anchored in a short (right after the action), or even very short (during action) time-frame: the so-called “immediate” or short-loop feedback process.

4.2.1.1. The “immediate” feedback process

The “immediate” feedback process can be defined as the systematic and repeated evaluation of the actions that contribute (or have contributed) to the completion of a collaborative project, as well as that of the team members’ observations and interpretations.

From formal and informal discussions, the team members are encouraged to discover independently what is happening (or what has happened), why it is happening (or has happened) and to see what lessons can be learned in terms of individual progress and collective performance.

The “immediate” feedback process, occurring during or right after the action, helps the actors reconstruct the live situations step by step, be they routine or unforeseen, as well as the management modes that were applied to them. They can thus easily identify the individual and/or collective mistakes that were made, discuss the different options they could have chosen, focus on the lessons learned and implement them during the next stage. The learning loop, therefore, rests on the ability to learn together, during and from the action. It feeds the collective skills and helps teams progress in the completion of their missions by revealing complementarities and synergies taken from the analysis of errors [RON 06].

The military environment is familiar with the short-loop feedback process. Indeed, armed forces have been practicing it for decades, only considering the mission finished once it has been debriefed. This is indeed the case of the Air Force’s Aerobatic Team, on which we will now focus.

4.2.1.2. Air Force’s Aerobatic Team: who is it?

The AFAT is located on air base 701 in Salon-de-Provence, France. It consists of six pilots, six mechanics, two operations agents and two cameramen. Apart from the fact that the pilots benefited from aerobatic flights during their initial training, every team member has a background in fighter aviation and has solid operational experience from his or her original career. Nowadays, the team consists of newly-arrived pilots, possessing experience in national and/or international aerobatic flight competitions, as well as older pilots, who have earned their experience throughout the years spent in the AFAT. The aircraft commander is one of the six pilots. The rest are likely to take over “supplementary” activities (for example, external communication and events planning), undertaking these in addition to their piloting tasks. Working closely with the pilots, the mechanics’ responsibilities include the implementation and maintenance of the AFAT’s three Extra 300 aircraft.

As briefly mentioned in Chapter 3, the Aerobatic Team must carry out two missions. First, it intervenes in military and civilian aerial meetings. The meetings mainly take place during the summer season, the winter season being set aside for training. The meetings allow the general public to be introduced to the field of aerobatic flight and to convey a positive image of the French Air Force. As explained by a pilot: “During an aerial meeting, we are putting on a show. We need to act as artists, trying to arouse emotions”. Moreover, the excellent quality of the maneuvers being presented guarantees to leave a good impression, which then benefits the aerobatic flight community at large. These performances, therefore, involve the team as an entity, each flight crystallizing a collective know-how.

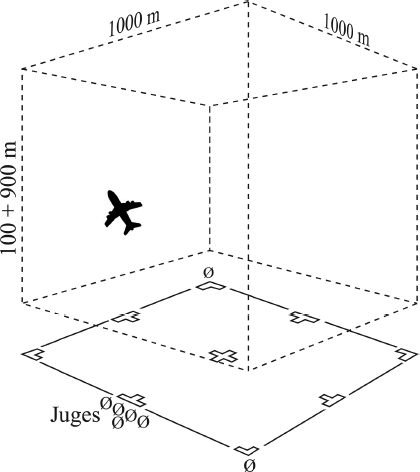

The AFAT also participates in national and international competitions. In the last few years, the team has achieved the best possible results. It has in fact won the gold medal in the Unlimited World Championships (the highest category) in 2009, 2013 and 2015. In the individual categories, the first place was also awarded to AFAT pilots. The results for the 2010 and 2014 European Championships confirm once again the high level of excellence, as the team won a gold medal. During the competitions, the pilots execute mandatory programs (known to the pilots, made available to them several months before the competitions, and unknown, where the requested maneuvers are unveiled a few hours before the flight) and freestyle, judged by a panel of 10 judges. The different programs are executed in a space of 1 km3 called the box, and symbolized on the ground by marks (Figure 4.2). The judges rate the execution of maneuvers and sequences with marks out of 10, the applied coefficients being directly correlated to the proposed level of difficulty. The pilot’s ability to develop inside his box (without leaving its limits and respecting the flight safety regulations) is also rated. The competition is also marked by individual dynamics, as pointed out by a pilot: “Aerobatics is an individual sport. People are not selected for their ability to be nice, but for their competitor skills. That means everyone is fighting for the top spot”. The selection and training of military pilots is carried out by the federal trainer, under the authority of the French Aeronautical Federation’s National Technical Director (the AFAT’s aircraft commander also participates in the pilot’s selection). The federal trainer himself is a former military and world champion.

Figure 4.2. Aerobatic team member’s competition space: the “box” (source: www.equipedevoltige.org)

Good coordination within the AFAT rests on its members’ ability to collectively generate meaning from the two types of missions they must carry out. As pointed out by Alsène and Pichault [ALS 07], this collective construction (the authors refer to this as the search for coherence) highlights both the importance of the orchestration of activities (organizing resources and individual efforts) and their harmonization (each team member shares the same representation of his environment and agrees on the means necessary to accomplish the objective). At the AFAT’s level, it becomes a question of managing the logistical aspects of the presentation and competition activities (personnel allocation, aircraft availability, pilots’ and mechanics’ workload management, time schedule planning, etc.) and a question of integrating its members’ knowledge and skills so that each one develops in the same direction and contributes to the excellence of meetings and competition results.

4.2.1.3. “Immediate” feedback in order to build and cement the collective

When answering the question: “What does the feedback process naturally mean for you?”, the AFAT’s members being interviewed all converge toward the same answer: the transfer of savoir-être and “savoir quoi faire” (knowing what to do). A pilot states: “We do not talk about theoretical knowledge here. We discuss sensations, ‘steering buttocks’ as we’re used to saying”. Another specifies: “This is pure piloting, where sensations are essential. For instance, if you want to know where to put your foot to trigger a figure, you won’t find the answer in a database! Theoretical knowledge is good, but has no value if it is not put into practice”.

Marked by the experiential nature of the knowledge it can transmit, the feedback process in the AFAT rests on specific practices. First, the transfer of knowledge is mainly accomplished from informal discussions and dialogues, one-to-one and as a group: “You cannot find experience in a textbook, it is transmitted orally and it is lived”. These exchanges involve the pilot and the trainer in all the competition flights, the pilots and mechanics when it concerns flight meetings. A pilot explains: “The feedback process is mainly word-of-mouth amongst ourselves. I sincerely think the most efficient feedback process is done between men. Paper, video,… those only represent tools that allow for only a partial transmission of the knowledge we acquire year after year”.

The feedback process’s “oral tradition” is made possible first due to the use of common languages, as previously discussed. Whether it be the Aresti code (diagrammatic transcription of aerobatic maneuvers) or body language or expressions, these shared languages, far from hindering informal discussion between members, facilitate it by allowing them to get straight to the point without needing long introductory descriptions. A pilot states: “Within the team we all talk the same language, certainly because we share aerobatic’s language and knowledge (military and civilian). I believe that is the reason why giving feedback is done naturally and quickly between members”.

It also appears that the sharing spaces, such as the squadron bar, favor this informal feedback process more than others. The AFAT members meet there in order to continue sharing their experiences, recent or otherwise. A mechanic recounts: “We always meet here in the same space, in the morning or in the evening. And a lot of things are said in the café. For example, when we come back from a meeting, us mechanics who have gone with the pilots start talking to the other ones (the ones that stayed) in an informal way: you need to use this setting for this pilot in order to avoid aggravating his tendonitis, etc.”. Pilots, mechanics and administrative personnel know they will meet daily at the squadron bar and take advantage of the opportunity to chat. The mechanic continues: “In the squadron break room, a lot of problems are solved. It allows us to communicate with the right people, while discussing with them. Which is why having spaces where people meet and communicate freely is essential!”.

The feedback process within the AFAT is particularly “immediate”. One of the interviewed pilots explains: “The transmission is fairly immediate. We perform short flights, of about 15 min, and give feedback either during or right after the flight.” In the first instance, a second aerobat (either one of the pilots or the trainer), located in a central position, that is a place where he will have a good field of vision of the maneuver taking place. A cameraman routinely accompanies him in order to film the flight. The person in the central position has radio contact with the flying pilot, and is thus able to offer his comments (and criticism) as it happens.

Another pilot explains: “Aerobatic pilots need to hear their trainer’s voice punctuating the maneuvers, severely criticizing what they are doing, all in real time. It allows us to immediately put the feedback into practice, to repeat the maneuvers, over and over…”.

The person in central position can also record his comments as voice-over, which will accompany the flight’s video. This is the second type of immediate feedback: right after landing, the pilot enters a small projection room where he inspects his flight along with his colleagues. As made clear by the trainer, the pilot is no longer in the action phase, he is in a reflexivity phase: “I record my comments as a voice-over, which the pilot will only hear once the flight has finished and is watching the video of his flight. He will scrutinize his performance, observing any errors he will have made, as well as recognizing what he has done right. Why he succeeded this maneuver and why he failed that one are answers he must obtain, with my help or that of a colleague if necessary. He must take a step back in order to apprehend his state of mind during the flight’s key moments; he must learn to know himself in order to progress. It involves self-criticism and the acceptance of the others’ (constructive!) criticism”.

These informal and “immediate” feedback processes constitute a key source of cohesion within a team, torn between its objective of demonstrating a collective savoir-faire during meetings, and collective and individual results during competitions. Under these circumstances, it is in the interest of the pilots to invest in the feedback process, in order to benefit, and have others benefit, from their own knowledge in order to progress. However, the competitions are naturally marked by more individual dynamics: “People are not selected for their ability to be nice, but for their competitor skills. That means everyone is fighting for the top spot. Even if nowadays we are world champions in the team rankings, we all focus on individual rankings. The team rankings are a consequence of our individual know-how, not an end in itself”.

Military pilots are now among the best aerobat in the world and directly compete against each other. They could consequently perceive the feedback process as a potential danger, as it encourages the spreading of knowledge that is crucial in order to win. One of the pilots rejects this idea: “A flying pilot who keeps all the information for himself, that could be conceived if he is in the running for first place. In my case, I am currently in the leading position, and of course I feel threatened! It is an unstable balance. But withholding information, hiding stuff… That’s not how we want to win. I want to keep giving and receiving feedback”. In consequence, beyond just a process of knowledge transmission, the feedback process is seen as a way of raising the contestants’ level, a source of emulation and a way of always facing people better than themselves.

Thus, between meetings and competitions, the members of the aerobatic team constantly alternate between collaborative and near competitive interactions. The coexistence of supposedly opposite attitudes seems to be made possible due to the experience of giving and receiving feedback. Indeed, the practice of sharing experiences evokes a process of intermediation, a sort of bridge between the competitor attitude on one hand and the presenter on the other hand: “The collective is actually built around a quite unusual balance: the competitive spirit, very individualistic, that leads us to want to defeat everyone. Then there is the team spirit, which is essential to the survival of the AFAT, which must show its know-how and communicate in order to continue to exist. By broadcasting the videos of the flights, the way in which we succeeded this or that maneuver, the mistakes to avoid, the feedback process helps us measure all that out” (from an interview).

Furthermore, by facilitating social interactions, the feedback process creates cohesion, bonds a team. One of the pilots explains: “The feedback process plays a part in the team’s cohesion. First because we see the way in which others work, their level of expertise, and that builds confidence. Also, because it allows us to get to know the others beyond their technical abilities and expertise. The feedback process allows us to approach them differently, better understand their personality, their attitudes”.

The trainer explains: “The human environment is paramount and the team is interesting when the members get along and complement each other. Members must be united and they build this cohesion mainly by sharing their professional experiences. For example the pilots meet often to watch their colleagues’ videos. This is a group debriefing of an individual’s performance. Sometimes the criticism is harsh, but they must also know how to encourage themselves. Everything must be done in a constructive spirit. It is pointless otherwise, the collective will be poor and so will the results”.

4.2.2. “Immediate” feedback: a method of collective skills and intelligence acquisition

The “immediate” feedback process provides the collective with skills to act, coordinate and adapt articulation in extreme environments. It represents a mode of managerial action allowing articulation of the practices of coordination identified and described in Chapter 3.

First, based on eminently reflexive practices and processes, “immediate” feedback nurtures the collective’s ability to criticize the way it functions, create a consensual interpretation of a situation and maintain meaning. Throughout the confrontation of individual representations and the sharing of singular experiences, the team members progressively devise a “common baseline” [RET 05], which they refer to in order to achieve their missions: they agree on what should be done in order to accomplish their objectives and implement the required measures. Their conflicting viewpoints and constructive criticism significantly contribute to good coordination within the teams.

Second, the communication practices around their common languages allow the team members to free some cognitive load and save time during their explanations. Informal communication, which is quick and efficient, is made possible due to the repeated reference to standardized languages (for example, the Aresti Code). These also favor a collective foothold while sustaining the identity and social aspects of the group: integration within the group is necessarily accomplished through the acquisition and use of these languages.

Finally, the “immediate” feedback process spurs the players on to “subjective commitment” [RET 05]: they get involved in socialization practices and approach problem-solving in a collaborative way. This last characteristic plays a key role in extreme environments: the good coordination of teams rests on the members’ ability to quickly find solutions together. By involving themselves in their collective lives, caring about each other and wanting to get to know them, the actors progressively build the mutual trust and knowledge, which will favor the team’s “synergy” in the face of unexpected situations.

It becomes apparent that the “immediate” feedback process fits into and nurtures both action-based learning and an experience accumulation dynamic at the collective level. The analysis of the AFAT highlights the existence of different temporalities that overlap with each other during the implementation of the feedback process, where diachrony and synchrony coexist. This articulation of different temporalities is accomplished in the following way: iterations within the team, performed during or right after the action, favor the accumulation of experience-based knowledge and collaborative skills in the long term. In this context, feedback does not operate linearly and sequentially on collective skills; instead it adheres to tangled temporal structures, which interact with each other. On a daily basis, the team members both co-construct and commit to these temporal processes. Thus, the collective skills develop from the actors’ simultaneous engagement in the short-term and long-term time structures.

The exploitation of these feedback temporalities is made possible due to the specific structuring of roles, based on intermediate management. The manager must know how to mobilize and unify the actors as a collective entity, without suppressing any individual skills. It is a question of managing the interactions between actors and articulating their practices (communicative, reflexive and social) with the organization’s aims, while adopting a proactive stance. For instance, in the case of small team, informal debriefing, an integral part of the immediate feedback process, plays a key role. In particular, it nurtures socialization and reflexivity among the members, of which we have previously outlined the key role in coordination in extreme environments. This highlights the importance of managerial stimulation to create the conditions for the emergence of these practices, as the actors’ willingness on the field does not always suffice. They need their manager’s support in their efforts; the manager must know to encourage them to interact and share on a cohesive basis, for example by encouraging them to regularly share feedback by planning the team’s time schedules and/or by suggesting and preparing spaces where they can relax and share experiences. The absence or the lack of these types of incitation can lead to a lack of coordination.

4.3. Deploying decision support systems: the example of LINK 16 in air forces

Coordinating teams in extreme environments requires thought in terms of decisional collective skills. These are applied mainly when the teams are confronted with unexpected situations and must act rapidly outside of or adapt their usual frameworks. The team members must then “know what to do” (individual situational skills) together (synergy and collective intelligence) in order to agree on a solution that will be suited to the context. The creativity of the process and the decisional result thus reveals itself to be essential.

The information systems and technologies that comprise them can play an interesting role in supporting teams in their creative resolution of problems with which they are confronted. The DSS can “generate new courses of action and produce new and useful ideas” [WIE 98]. This last section illustrates the DSS’s contributions to the collective creative process [GOD 12b].

4.3.1. Creativity and network-centric decision support system

Generally, creativity is defined as the production of ideas, goods, services and/or processes, that are new and add value to the organization [AMA 88, WOO 93]. It can refer either to skills (individual or collective), or a cognitive process, its result and environment:

- – The actors’ creativity depends mainly on their character traits, skills and particular aptitudes. Csikszentmihalyi [CSI 96] insists mostly on the combination of imagination and the meaning of realities, as well as on the ability to persevere in the study of a subject. This permanent attention, which recalls the actors’ daily approach to “immediate” feedback, allows the actors to exploit each element they live in order to construct new ideas. From a collective point of view, creativity is considered through the dynamics of the sharing of knowledge and experiences within and among teams (which can potentially take place, as we will see in the following section, within professional communities).

- – Creativity then refers to the complex cognitive process tied to individuals’ skills, to available information, and to the combination of the two. The founding works of Wallas [WAL 26] identify four stages preceding the process of creativity: the preparation stage, during which the experiences, knowledge and contextual information are gathered; the incubation stage consisting of the combination, in the form of the association of ideas, of the whole of these elements; the illumination stage, during which the ideas flow finally, the verification stage, during which these new ideas are tested against reality. Analogical reasoning, based on the confrontation of sources of inspiration, thus finds itself at the center of this process of the emergence of new ideas.

- – Creativity can also be considered as a result. In this context, a creative solution rests on a process and/or a product that has not yet been explored and/or developed by the actors, and that adds value both at team level and organization level [SEI 10].

- – Finally, creativity is closely tied to the environment where the teams develop, which includes the resources available to them, the degree of autonomy they benefit from and the way in which their members communicate [AMA 88].

4.3.1.2. Network-centric decision-support systems

In the last 20 years or so, the work in information systems management has questioned the contribution of DSS to decisional creativity, be it individual or collective [FOR 07]. Such systems permit us to see the bigger picture regarding the problems to be solved, exploring new points of view and implementing original decisions, adapted to different situations.

This is the case for a particular type of DSS, the network-centric DSS. These provide users with the precise visualization of a situation while (1) integrating geographical data, (2) manipulating data in the form of layers (each layer gathering a particular type of player) and (3) allowing the drilldown (possibility of zooming into a particular element’s characteristics and zooming out to a global view). Resting on a structured network, the networkcentric DSSs regularly and closely collect and spread available data, updated in near real time. They retrieve, organize and analyze the data in order to provide decision-makers with a representation of the problem they need to solve, namely (1) a graphical visualization of the elements of interest associated with the problem and (2) links between these elements.

Network-centric DSSs are particularly well adapted to (individual and collective) decision-making in extreme environments. They provide a global view of the action’s environment all the while allowing for a manipulation of the data. These technical characteristics allow the decision-makers to access a situational awareness [END 00], to devote their attention to construct meaning, and then develop and stabilize their understanding of what must be done. In this way, network-centric DSSs support the so-called naturalist or intuitive decision-making [KLE 98]: inscribed in an initial reconnaissance process, the intuitive decision is taken by the experts mobilizing their past experiences in order to manage the situations they experience. Far from comparing various options with each other (analytical and satisfying decision process), they work analogically in order to adjust their decisions to the uniqueness of the problems they must solve. In this context, the “intuitive” decision-makers do not need a system capable of generating options from which they can choose (model-oriented DSS), rather, they need access to a rigorous representation of their environment of action (data-oriented DSS), which allows them to give meaning to the situation [LEB 06].

Where does creativity come into play in the naturalist decisional processes supported by network-centric DSSs? The following section aims to suggest answers while describing the creative uses of a military system that equips the French Air Force Rafale fighter planes: LINK 16.

4.3.2. LINK 16’s creative uses, developed by the Rafale fighter planes’ crews

4.3.2.1. LINK 16: a description

From 2006, France has progressively equipped its Air Force with American Joint Tactical Information Distribution System (JTIDS) technology. Also known as LINK 16, this system has been implemented on board the versatile fighter plane Rafale, the command and control aircraft Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) and several Mirage 2000Ds. We will focus mainly on LINK 16 equipping Rafale.

Resting on a highly secure reticulated structure (encryption system), LINK 16 supports the tactical data exchange necessary to (aerial, terrestrial and marine) military teams’ coordination, particularly fighter crews consisting of a pilot and a navigator. The data collected by the various sensors spread over the combat zone (human and technological) are fused by LINK 16, which elaborates a coherent graphical and updated representation of the field situation. This representation is broadcast to the different players involved in the operation, such as the high command and Reachback (the Pentagon in the United States or the Operation Planning and Command Center in France), the tactical command centers located on base (that is the terrestrial, aerial or marine zones where the military operations take place) or the teams involved in the missions. A staff officer explains: “Tactical information can be relayed thanks to the linking of data, which allows us to communicate in digital form any flight information, to the ground, to another vector such as AWACS or to other Rafales”. Teams can be both LINK 16 users and “sensors” (as they also collect information), to the extent where the data collected during their missions contribute to the tactical representation’s update.

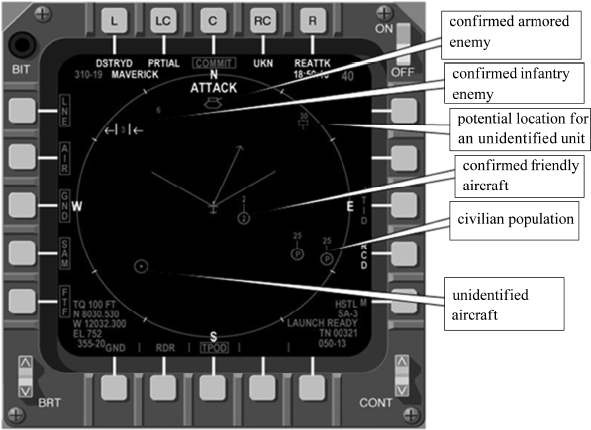

The tactical data being exchanged and exploited by the pilots using LINK 16 can include enemy and friendly forces’ positions, fuel levels, available weapons, meteorological conditions, target coordinates, emergency airfields and tanker aircraft positions (Figure 4.3). LINK 16 also provides them with communication capabilities via a common language (code words and J-series data) that facilitates their coordination in any situation.

Figure 4.3. Example of a tactical reepresentation provided by LINK 16 to a Rafale crrew (or pilot)

All of these services allow users to improve their grasp of the situation. As they specify during interviews, LINK 16 facilitates simultaneous acquisitions:

- 1) The perception of environmental elements in a volume of space and time: “The first thing we share is each participant’s position and that of enemy forces, because when you know where each player is at any point in time, coordination becomes easier” (a Rafale pilot).

- 2) An understanding of their significance: “With LINK 16, we permanently know where friends are, where enemies are, and we get a global view of the situation” (a Rafale pilot).

- 3) The ability to anticipate their own evolution: “For example, LINK 16 shows us tankers, which allows us to graphically see in our zone if a tanker is about to go back because it is already supplying another patrol, so we adapt ourselves. We are always one step ahead” (a Rafale navigator).

LINK 16 offers an unprecedented serenity and comfort, both in terms of apprehension of the environment surrounding the action and reactivity in the face of threats. In order to illustrate this, a pilot explains: “LINK 16 provides information updated by various sensors. This results in increased comfort, as the friendly and enemy positions are known and the tactical situation thus easily and instantaneously shared between members”. These general observations naturally lead us to question ourselves about the creative implications of such a system. What are the effects of LINK 16 on the user crews’ creativity?

4.3.2.2. During flight: creativity in the process of elaborating aerial tactics

LINK 16 improves crews’ abilities to detect and implement using available opportunities during flight. By providing pilots and navigators with tactical information in near real time, LINK 16 allows them to gain an unprecedented grasp of the situation. A pilot uses the following metaphor: “Imagine you are in total darkness, in an area you don’t know, and are made to run and all you have is a torch to see what’s in front of you. With LINK 16, it’s as if someone turned on the light inside the room before you started running. All of a sudden you understand what you need to do and how to do it”. Regarding any unforeseen situations of a tactical nature (for example, unexpectedly detecting an enemy aircraft, a commando unit suddenly being trapped and needing assistance, etc), crews can manage them in real time. A navigator specifies: “Between what was planned and what you actually live during flight, things can be potentially very different. The unexpected is discovered in the moment, and we need to know how to adapt in real time”. Without LINK 16, these situations become more difficult to manage, as the crews do not benefit from as fine and updated a tactical representation. A Rafale pilot recounts: “Data-linking is a huge revolution. In big COMAO [Composite Air Operation – a set of devices having different capabilities and missions but needing to work together], those that had LINK 16 didn’t talk, they didn’t need to: they saw everything, while the ones that didn’t were constantly requesting information: ‘request picture, request picture!’”.

Furthermore, without LINK 16, crews would take off with a potentially very imprecise representation of the action’s environment and of the problems they would be facing. It all depends on the quantity and reliability of the information collected beforehand. On a base such as Afghanistan, for example, where the theater’s physical characteristics and the presence of combatants among the civilian population made the acquisition of information particularly difficult, it was not unusual for pilots to take off with a rough knowledge of threats and upcoming enemy tactics. A Mirage 2000D navigator assigned in Afghanistan, unequipped with LINK 16, explains the conditions under which his bombardment missions were carried out: “During CAS [Close Air Support] we don’t always have an objective. You need to take your own side’s position, the collateral positions and the environment into account. You have drones, FAC [Forward Air Controllers – ground-based personnel indicating targets to aircrafts] if it’s dark or if you need to create a show of force or if you’re in the mountains or under layers… And none of that is planned”. Without LINK 16, crews thus devote a big part of their cognitive resources to tracking and identifying risk, as well as anticipating enemy maneuvers, on the ground or in the air. All piloting tasks, as well as environment management and rapid three-dimensional evolution, are of course added to this mental burden. As explained by a Rafale pilot: “Those without LINK 16 are constantly mentally calculating. You need to understand them. They calculate, they calculate… That takes time!”.

With LINK 16, the cognitive load dedicated to treating information is considerably lightened: “With LINK 16, you can use more of your mental abilities, you are significantly less overloaded”. The visual representation offered on screens relieves crews of cumbersome calculations: symbols and colors are unambiguous and facilitate the situation’s understanding. A patrol leader explains: “For instance, I will look at the symbols and quickly see if my crewmen targeting correctly”. Furthermore, the fact that the data about the theater are updated in real time saves the crews from a laborious mental construction regarding the action’s environment. A pilot states: “With LINK 16, you no longer need to construct a mental representation of the tactical situation. The system does that for you! As such, you can focus a lot of your mental abilities on the tactical plan, and are not as overloaded”. The Mission Commander on AWACS insists: “With Rafale and LINK 16, information management tasks have significantly diminished, a few of them now being carried out by the system. Because of this, AWACS crews can be more focused on the actual aerial space control missions”.

It is in this context that an improvement on flexibility supported by the system can be observed. This comes to light in the adjustment of tactics during action in relation to the environment’s characteristics. A pilot explains: “When situations are complex, human judgment becomes paramount and is what allows good decisions to be taken. LINK 16 helps us understand what is happening and adapt to that”. In this case, tactical opportunities are more numerous: choreography as was imagined during the briefing stage can be readjusted in situ by the crews, and more specifically by the formation leader in charge of mission management. One of them explains: “We have the possibility of using radio to a much lesser degree […], we have the possibility of using our weapons thanks to LINK 16 […], information can be filtered during transmission/reception. You can also type things in by hand with LINK 16’s free text [on the Mirage aircrafts], which means we can now give indications or whatever else”. The time saved due to the system is allocated to analyzing the situation and adjusting tactics.

This does not mean that the actors find themselves in a situation of complete improvisation, in the sense that they have considered a set of scenarios during the preparation phase and the appropriate responses to implement. A pilot explains: “We are not reinventing the wheel. The basic tactics are always the same. Where we are going further with Rafale, is with the linking of tactical data and all the possibilities for tactical refinement it offers!”. In addition, crews evolve in a highly regulated and constrained environment. When they find themselves on an outdoors operation base, for instance, the rules of engagement, determined by the political sphere, precisely stipulate how much flexibility they have. Finally, readjustment is done under the supervision of a leader, who continually updates the symbols and colors on the pilots’ screens. A crew member explains: “I shot and it suits him [his leader] somewhat… and if it suits him and I haven’t he’ll place a pointer on the target”. In other terms, each pilot and navigator is creative in relation to his level of responsibility (which is directly correlated with his level of qualification), of which he is aware and accepts without condition. Under these circumstances, a synergetic and harmonious in situ reorganization of the formation is observed.

4.3.2.3. On the ground: creativity during scenarios’ preparation

Mission preparation is primarily developed during briefing, right before flight. The crews are informed of the theater’s characteristics and potential danger, and tackle tactical questioning, the method of progression as well as each of their roles. They also agree on the elements of communication (code words), and the frequency at which they will be used. It is a question of organizing the mission’s progress, with the leader as an orchestra conductor. The leader makes sure that everyone knows what to expect, what to do and under what conditions.

As suggested by the data collected from Mirage 2000D pilots and navigators who are not equipped with LINK 16, any unexpected situations are only evoked from a technical point of view. With LINK 16, due to the acquisition of a precise and updated representation of the tactical situation, the process of anticipating unforeseen situations during the mission’s preparation stage improves, particularly from the implementation of increasingly sophisticated scenarios. A pilot illustrates: “The problem with aerial combat is that if you can see an enemy aircraft, they can see you too. With LINK 16, you don’t always need a visual. You can send a plane that will lure the target while another, who will have turned everything off and become undetectable, waits for it in an ambush. Obviously these new possibilities are taken into account during briefing!”.

The leader can thus afford to imagine critical and complex situations (larger enemy numbers than previously expected, failing ground defense systems, etc.) and prepare his crews to face them by considering the appropriate response. The actors project themselves into these situations even more easily if the risk of friendly fire, collateral damage, collision, etc., is considerably reduced, if it has been discussed during the briefing: LINK 16 allows a better sharing of the tactical situation, thus contributing to limiting the risk of firing errors, collateral damage and friendly fire. This way, pilots are no longer compelled to limit themselves to technical problems during a briefing, in the sense that they know they can rely on a system that will provide them with reliable and appropriate information for dealing with the criticality of the situations.

A pilot insists: “LINK 16 opens up a lot of doors, in the sense of what can be done with it! It has revolutionized the way in which you use a fighter plane”. Another emphasizes: “LINK 16 offers new opportunities for the aerial tactics that need to be implemented […] it impacts the game plan, that is, the way in which the mission will be carried out in relation to the situation’s evolution. And LINK 16 gives us a lot of new possibilities. If I turn off my radar, for instance, my enemy can no longer detect me. I become inconspicuous, whereas I can see everything on a 360-degree radius. I could come up from behind for example. In fact, it opens up huge doors, and this is only the beginning!”.

By coming up with original tactical scenarios, crews also heighten their vigilance before a mission. They mentally construct the way in which the planned scenarios will be visually presented by the system (generic symbols showing positions, colors, etc). A pilot explains: “With LINK 16, I know I’ll get a global view, but what is most important is that I will build a mental diagram of what we are going to do and what the others (the enemy) will do”. As a result, the stress load associated with the management of unexpected situations is diminished. In order to explain the decrease in stress, a navigator describes the following: “We go on a planned mission and, all at once, our chain of command considers that we need to make an urgent strike on a certain spot. Once it has the coordinates, it sends them to C2 [Command and Control], which sends them back by LINK 16 and, bam! A target will appear visually on the screen!”.

Likewise, after a mission, during debriefing, LINK 16 is used in addition to other mission progress playback systems. A navigator outlines: “During the debriefing, because we have recorded all our displays, we can see exactly what our shooting times were, as well as distances, for example. We report all the data on conventional debriefing systems and get a very clear vision of what happened.” Thus, the pilots analyze all the opportunities taken during the mission, the tactics implemented, and the potential errors that were made. These discussions contribute to and enrich the common knowledge base.

LINK 16 thus offers its users the possibility of expressing their creativity in the construction of mission scenarios by improving the representation of events that can happen during flight, and by growing the field of responses that must be implemented in order to face them. In this case, the briefing’s orchestration is built from a more open and complete script than ever before.

4.3.3. Network-centric decision support systems in support of crews’ creativity

The analysis of LINK 16 helps refine our understanding of the role played by network-centric DSS on creativity’s all four dimensions (individual/team, cognitive process, result/product/service and environment).

The system allows for a reduced cognitive charge for the players and teams in the extreme environment. Because of this, they have more time and resources available to imagine new avenues in their missions’ predefined frameworks.

Back in the field, the flight crews’ (pilots and navigators) characteristics have a strong impact. Indeed, they all have a high level of technical abilities, coupled with a decided taste for exceeding limits.

Without these characteristics, the workload, which is not managed by the system and which the pilots must process themselves, would be too much to bear and would not leave them with the possibility of deciding creatively, that is enriching tactics decided in advance.

LINK 16, while improving information display and organization during the creative process’s preparatory stage, contributes to enriching the possibilities for action, and thus the opportunities to elaborate more creative maneuvers. By offering a new workspace, LINK 16 becomes a source of inspiration during the generative stage: players can imagine new action processes and collectively simulate the results before they are even implemented. As a result, even if the crews do not use the actual network on which the system rests during the action’s preparation stage, they project the benefits to construct new action processes. During the mission, the DSS also supports exploratory work since, by freeing their cognitive abilities, it allows the teams to put their representations through a field test and elaborate maneuvers destined to adapt themselves to complex situations. The individuals are creative because they can rely on processes both prior (inspiration and simulation) and contributing to the action (experimentation and adjustment).

A DSS such as LINK 16 considerably improves decisional performance both on an individual and collective level. Indeed, by exploring the scope of creative liberty offered by the system (before/after action process), the teams are capable of carrying out their missions more efficiently. The increase in their capacity for anticipation improves their coordination by favoring a reduction in the surprise effect: indeed, the system allows the teams (1) to consider a large set of unexpected situations and (2) to free the cognitive space they will need in order to manage the switch between routine and unforeseen situations.

Deciding and coordinating oneself in extreme environments implies knowing how to articulate significant and compulsory action constraints (rules, procedures, etc.) all the while knowing how to adjust to continuous change. While literature tends to consider that DSS should favor the absence of constraints, in order to unleash the creativity of the spirit, it can be observed, on the contrary, that the implementation of new constraints (while LINK 16 is indeed a flexible DSS, its data collection and spreading possibilities follow a strict structure, set by the characteristics of its use) leads to a redefinition of the workspace which favors the emergence of new action processes.

The users’ creativity in extreme environments is thus expressed within a context that is defined both by its limiting aspect and enabling capacities.

On a more detailed level, it is the system of iterations between the representation of the mission’s elements, the opportunity taking and the scenarios’ enhancement, which is at the root of creativity. By offering the teams a display of the problem’s elements and the links between those elements, the network-centric DSS allows:

- – an improvement in the understanding of the situation, and a presentation of most of the parameters the teams will need in order to act efficiently, since the system offers additional information they will be able to associate with experiences and knowledge they already have;

- – experimentation with new maneuvers, a more refined adjustment of action tactics and taking opportunities that present themselves, thus favoring a synergetic and harmonious reorganization of decisions. This opens up the possibility of looking for the best ways to adjust to the situation, or even experimenting with planned scenarios;

- – imagining solutions more sophisticated and complex than before.

In terms of creativity, DSS plays the role of the inspiration source, allowing the teams to approach the situation in an original manner, and imagine varied solutions and motions.

Thus, even if the system’s primary purpose is not to favor creativity, it does so. This constitutes a major result: first, a network-centric system offers both a global view of the stakeholders and a handling flexibility allowing the user to imagine original combinations.

Second, the system is integrated into a global organizational procedure, which includes moments of interactions and reflexive discussion. These moments appear necessary to the crystallization of ideas and therefore to the emergence of creativity.

The case previously described finally allows us to highlight creativity’s collective aspect, which is clearly shown here. In this way, each mission can be conceived as an original collective creation. By drawing a parallel with music, it can be noted that teams cannot only choose between a large number of songs, but they also have the possibility of improvising around a score, all the while under the control of the team manager (or patrol leader in our case). With support from the network-centric DSS, teams, having a high level of expertise and regularly sharing common experiences in highly limited environments, elaborate scenarios together. They perform them in situ and adapt them to their environment.

4.4. Encouraging the emergence of professional communities: the case of Air Force Knowledge Now

Military teams perform operational functions that are clearly defined and directly related to their intervention environment (for example, anti-missile defense for the Navy, mild infantry operations for the Army and aerial defense operations for the Air Force). Their members are experts, in charge of developing and implementing skills (individual and collective) specific to the necessary operational and support functions for performing defense missions. They develop action principles and techniques, which determine and structure the division of work and the execution of tasks.

In order to finalize their objectives, the military teams can form professional communities. This is particularly the case in the United States, where the Department of Defense (DoD) supports the emergence of these kinds of collaborative spaces, in a budgetary, technological and (for the contributors) time management sense.

How can the participation of military teams in the different existing professional communities improve coordination in extreme environments? How do the players, by contributing to the heated discussions within these communities, improve their ability to manage the switch between the routine and the unexpected?

4.4.1. Professional communities in a military environment: between hierarchical communities and community of practice

At first glance, professional communities refer to what Cohendet and Llerena [COH 03] call hierarchical communities. These refer to the traditional functional groups that comprise the organization: more oriented toward action than toward knowledge, they are made up of individuals with homogeneous and complementary qualifications and knowledge. They develop their specialization by field or area of expertise. These types of communities do not leave much space for autonomy. The activity’s specifications and their control are formally defined and interactions between members are dominated by the vertical relationship to hierarchy.

Within hierarchical communities, however, identity and values relating to belonging to a group are of little importance. The strict codification of tasks, the specification of positions and the presence of hierarchy supposedly ensure the principles of cohesion. These elements bring to light the diverging aspects with professional communities such as they exist in a military environment.

Professional communities are indeed marked by cultural values and a strong identity [WIL 99]. Composed of intangible (for example, individual and collective postures and cohesive values) and tangible (for example, languages and traditions) cultural elements [SCH 92], the identity and cultural values translate representations of what things are and must be [HAN 06, RAV 06], they crystallize the meaning of collective action [FIO 91].

Indeed, identity and cultural values are the foundation of the ability of the professional communities members to define themselves as part of a collective [COR 03]. They are revealed as particularly important in military operations, where values of belonging to a group constitute the guarantee of its success. These cultural characteristics recall without contest what Brown and Duguid [BRO 91], Orr [ORR 96] and Wenger [WEN 98] write about communities of practice, when they consider identity as a determining element in its members’ feeling of belonging and cohesion.