3

Coordination Practices in the Extreme Environment: Communication, Reflexivity and Socialization

What are the main categories of coordination practices produced and implemented by teams in the extreme environment? How do these practices articulate one to the other? By taking an empirical inductive approach, this chapter endeavors to answer these two key questions.

The cases developed are based on the daily work of French Air Forces. Relying on these cases, three main types of coordination practices will be highlighted: communication, reflexive and socialization practices. A combination of these practices provides teams with the capacity to manage shifts between routine and unexpected situations and to adjust according to context and event-related constraints and opportunities.

3.1. Communication practices

In the extreme environment, where volatility, uncertainty and significant risk coexist, actors are in search of updated knowledge referring to the specifics of their task in the team, and to the means to implement in order to complete these tasks. From this point of view, they need to be able to rely on communication practices that permit us to sort out pertinent from less pertinent information when in action. The analysis of the following cases will provide an opportunity to stress the role played by shared languages (verbal, pictorial or body languages) and paths of information and communications technology (ICT) uses. These communication practices foster mutual understanding of activities among team members: actors refer to them when developing their actions and managing interactions.

3.1.1. Shared languages: code words, diagrams and body expressions

3.1.1.1. Close air support operations in Afghanistan: the code words

NATO military forces within the Afghan theater (2001–2014) would describe the combat operations there as “asymmetric”, in the sense that forces in the field were highly dissimilar. The coalition armed forces had access to resources (technologies, weapons and logistic capacities) that conferred them an objective advantage over Taliban forces. Even so, the physical characteristics of the ground, the presence of combat forces among civilian populations and the geographic dispersion of units posed real problems. Despite the means of communication deployed, they were confronted with difficulties in information gathering and reliability. Moreover, the tactical situation evolved according to nonlinear dynamics, shaped by unforeseen contingences that were therefore by definition difficult to anticipate.

It is under these circumstances that the French Air Force intervened to support special forces operating deep in the territory. These combat forces considered a situation as routine when the mission was carried out as planned (briefed) before departure and the activity breakdown followed the usual formal standards. It is worth noting that air or land forces missions in all theaters are always carefully prepared based on intelligence provided by a group of experts (among them intelligence officers). For example, the air force fighter crews brief their missions just before take-off. They describe all flight phases, security procedures and finish with what they call what-ifs. This last stage raises the question of what should be done (what procedures should be applied) in the case of a system operation problem during flight, such as an engine failure.

Despite rigorous preparation, combat forces may face situations that were not briefed or were briefed during the what-if stages, for example, but whose probability of occurrence was low. In Afghanistan, it was not possible to plan for everything, since ground targets were scattered and moving fast. These unexpected situations generated partial or total breakdown of plans of the air force crews and Special Forces on the ground, increasing the mission’s complexity. The task breakdown was then called into question and combat forces needed to rapidly make sense of the situation in order for coordination to evolve. Under these circumstances, common language played a key role.

Let us consider the example of close air support (CAS) missions undertaken daily within the Afghan theater for nearly 13 years (in particular by Mirage 2000D fighter-bomber aircraft). These tactical missions were launched when forces on the ground asked for air support, either because they were facing immediate danger or because they had identified a target to be destroyed. CAS involved three main actors. The first two were the fighter crew: the pilot, who concentrated on flying the aircraft, strictly speaking, and fired gun(s); and the navigator, who was in charge of medium- and long-term tasks (electronic threat monitoring, radio frequency tuning, preparation and weapon guidance). The last actor was the forward air controller (FAC). As a member of a Special Force unit deployed on the ground, his role was to accurately guide the bomber aircraft so that it could deliver weapons while avoiding fratricide firing risks and collateral damage.

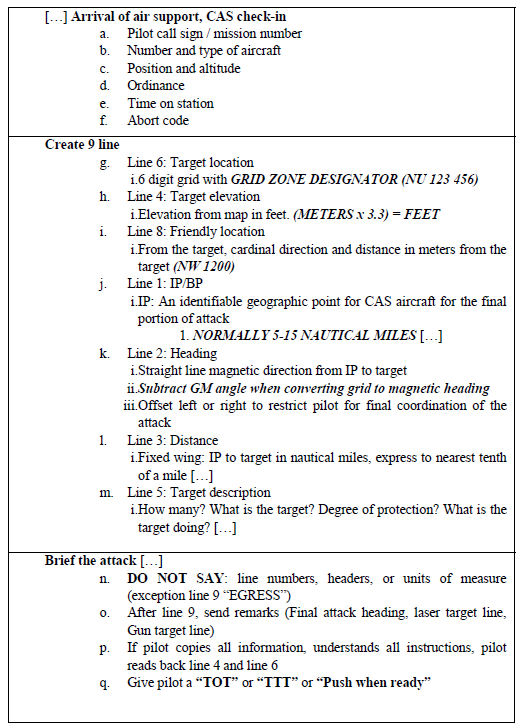

When the fighter crew was above the target area, it got in contact with the FAC. He then provided the pilot with all available information on the objective, based on a standardized information card called CAS Card, which contains in particular an operation check-list named 9 line (Figure 3.1). The 9 line consists of several “lines” of instructions and data that indicate geographic coordinates, objective entry and exit point, timing, etc., as well as various procedures to implement for mission execution. Once in contact with the aircraft, the FAC provided a real-time description of the environment in order to gradually lead the pilot to visually and unambiguously identify the target. As stated in 9 line, the description should inform the crew of the number of targets to be eliminated, their nature, level of protection and evolution.

As illustrated by the Control the attack section in Figure 3.1, war fighters used a common language, published in NATO documentation, which they usually call code words. Push when ready, Continue and Abort were all code words easily understandable by the crew members and the FAC, which facilitated communication, while significantly reducing the risk of misinterpretation. As a pilot noted: “These code words are rich with meaning. They are the basis of a common language, no need for interpretation or reasoning. For example [in an air defense situation], with Investigate one has to identify. It is a fact known from the start that a particular interception is conducted in order to observe and identify. There is no ambiguity. Code words are a real philosophy of communication”.

Figure 3.1. Close air support basic 9 line (source: http://www.imef.usmc.mil/staffsections/CAST/_Handouts/CAS%20Student%209-Line%20Handout.doc)

In Afghanistan, with one code word war fighters could concisely and rapidly exchange a significant amount of information. Everyone knew and had assimilated the code words. They contributed significantly to reducing comprehension problems, such as the risk of communication overload, for crews and controllers on the ground.

3.1.1.2. Aerobatic performances of the French Air Forces Aerobatic Team and Patrouille de France: diagrams and body expressions

Coded and shared languages are also used by more atypical structures of the French Air Forces, such as the display teams. There are two specific squadrons: the Air Force Aerobatic Team (AFAT) and the Patrouille de France (PAF). Their main mission is to present their program during military and civil aviation meetings: it is qualified as “free integral” for the AFAT pilots, and consists of a sequence of free aerobatic figures (except for security rules, they are not subject to any other rules), while the PAF performs synchronized aerobatics in eight-plane formation (Figures 3.2(a) and (b)). It is worth noting that AFAT also participates in national and international competitions where for severral years it has won important prizes (world champion in particular).

Figure 3.2. Performance by the pilots of AFAT (source: http://spoottingaviation.forumactif.com/t3398p280-mna-rochefort-28-29-mai-2011) and PAF (source: www.blog.francetvinfo.fr)

Display team members coordinate in an extreme environment: the situation may very rapidly shift due to unstable weather conditions, for example; there is high uncertainty as to the extent that unexpected events can occur, such as a bird strike, a mechanical problem or a radio communication failure; finally, the flight programs presented involve significant levels of risk: there is physical risk, as pilots’ life and health may be endangered, but there is equally a more symbolic risk, as the teams’ prestige and reputation are at stake.

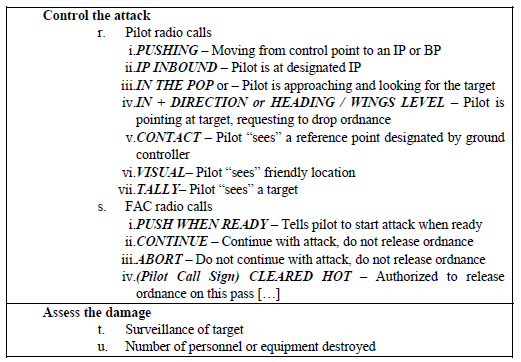

The pilots of display teams share a common language, just as those of the operational forces do. Beyond its verbal nature, this one is striking due to its pictorial and bodily dimensions. Members of the two teams first take advantage of schematization and drawing. For this purpose, the PAF uses a magnetic whiteboard and magnets in the shape of Alpha Jet (the fighter aircraft that PAF flies). They move the magnets on the whiteboard to symbolize the acrobatics, and write the technical elements required for the successful execution of the planned figures. AFAT members share a language that borrows from both the general aeronautics vocabulary and a code specific to aerobatics: the Aresti key (Figure 3.3). Published by the Fédération Aéronautique International (FAI), this code associates code words with simple diagrams that describe nine families of classical aerobatics figures. The diagrams consist of curved lines, straight lines and geometric elements representing the maneuvers to be performed by the pilot.

Figure 3.3. Example of aerobatic figures diagrammed according to the Aresti code (source: www.equipedevoltige.org)

Complementary to this shared pictorial language, and for coordination purposes, display team members develop practices based on body communication, appealing to sensations. Before each flight, pilots mime the aerobatic figures to be performed (Figures 3.4(a) and (b)); they “experience” the figures with their bodies before performing them with their aircraft. Members of PAF call this mental and body imagery “the music”. During briefing meetings, pilots simulate together the flight program, in a rhythm imposed by the leader’s voice. Sitting on chairs, most of them with eyes shut, the pilots express their future flight maneuvers with their hands, fingers, legs and head. The actors’ gestures are always the same, perfectly automated. For the AFAT, the exercise is substantially similar, except that only one pilot mimes the flight while his or her teammates, often present, are observing him or her. Furthermore, the pilot is outdoors (on the tarmac) and performs the body movements while inside a square marked on the ground (representing 1 cubic kilometer volume, called the Box, in which his or her competition flight will evolve).

Figure 3.4. Body language of AFAT (source: http://www.equipedevoltige.org EPAA@2010) and PAF (source: http://www.aerobuzz.fr) pilots

3.1.1.3. Shared languages: when faced with unexpected situations, automatisms improve comprehension and save time

In unexpected situations, teams’ and their members’ responsiveness and capacity to adapt prove to be crucial. When tension is high, everyone needs to work toward the overall coherence required to complete the mission within a very short time. To this end, the various types of language described above represent automated communication standards used by the actors. To the extent that they help save time, their role is crucial. More precisely, on one hand these languages facilitate communication between team members. Each code, either verbal, pictorial or bodily, is known by everybody and allows for rapid transmission of clear and straightforward messages. This significantly reduces interpretation errors. Actors understand each other without ambiguity. On the other hand, shared languages reduce the load of coordination and help free time for completing other less “routine” tasks that become a priority when unexpected situations occur.

Faced with the unexpected, actors take advantage of this time gain to reach agreement on the situation and on the adequate solutions for reaching objectives. There is a tendency to avoid code words and adopt more familiar language. A pilot shared with us: “In the combat theater, stress levels can be very high. In some situations survival instinct takes over. In such moments the important thing is to communicate, language doesn’t matter, even if everyone understands code language and we need to do our best to preserve it as long as possible.” Discussions may refer to the tactics to implement to deter the enemy (very low altitude flights, for example, also called show of force, were regularly used in Afghanistan) or the opportunity to fire weapons in a legitimate self-defense situation. A navigator remembers: “Last year I had a case when we decided not to fire weapons. […] We had the rules of engagement, what we could see below… The two of us discussed the opportunity to fire weapons. We agreed. And even if we didn’t, we would have discussed it longer. I think the decision would have been still a No, because generally when one doesn’t agree the decision is No”. Thus, natural language is adopted not because it is more effective than code languages, but because the war fighters are under such levels of tension and stress that they unconsciously activate deeply rooted patterns of action and communication. Through dialogue, they gradually move toward consensus on the processes to be implemented in order to coordinate when faced with the unexpected.

These shared languages help actors better comprehend messages and save time that can be dedicated to sense-making during unforeseen events. These results are made possible because, through training and operations, the acquisition of these languages by the team members reaches the level of automatism.

3.1.2. Technological uses: improving communication through information sources and flow

ICT also contributes to improving communication within teams. According to the classical view, this effect is seemingly linked to the technical characteristics of ICT, which directly impact the conditions in which information and knowledge are collected, exchanged and stored [ZAC 99]. According to this view, ICT are approached as mere technical means at the service of preexisting modes of communication [CAB 99], referring to a contingent perspective that gives little satisfaction when dealing with coordination in the extreme environment.

Because they transform the conditions in which information and knowledge are used, technologies are intrinsically linked to their (practical) uses: technical characteristics, the programming of the technological tool and the context in which it operates are inextricably linked to the social and structural effects (as defined by Giddens) of its uses [ORL 07]. Within this framework of analysis, ICT uses can be thought of as socially and materially entangled in the social systems, teams and organization structures (the specialist literature mentions a sociomaterial approach). The materiality of the technological artifact crystallizes a set of tangible resources that offer users the possibility to advance their practices and innovate the ways in which they are used [LEO 08]. The nature of tasks, the social interactions and the team roles may be modified, thus leading to a redefinition of social and organizational structures [ORL 07, ORL 08].

The following case illustrates the types of uses developed by American military teams following massive introduction of the so-called “network-centric” technologies [GOD 10]. The Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts have in effect been marked by the deployment of a doctrine qualified as network-centric warfare, defining the changes and principles of action associated with the ICT introduction for military operations management. The ICT interactivity potential has been massively exploited by the engaged armies to facilitate communication between units and to optimize commands and operations management.

Among the technologies deployed within the combat theater, tactical Internet has played a major role, strengthening the network-centric organization of NATO forces. Tactical Internet – a set of technologies such as the synchronous (text-chat and instant messaging, videoconference, satellite radio, etc.) and asynchronous (e-mail) communication systems as well as decision support technologies (evolutive databases, tactical navigation support and simulation systems) – has given access to a significant volume of information and has encouraged team work around a common view of operations. The following illustration focuses on one of the components of tactical Internet: text-chat. Text-chat is a real-time communication system that allows users to have a written and interactive conversation, through interposed keyboards. Messages are managed by Internet Relay Chat (IRC), a system that involves a protocol and a network of servers dedicated to this type of communication. The US Navy and the US Special Forces, in particular, have used text-chat during their offensive and defensive operations in the Afghan territory between 2002 and 2007. The analysis of results reveals the gradual production of innovative uses around communication, allowing significant improvement in the decision and coordination capacities of the military teams.

3.1.2.1. Multiplication of sources of information

An essential technical characteristic of text-chat is the multiplicity of sources of information available to users. On the Afghan theater, text-chat was configured to facilitate simultaneous creation and management of a multiplicity of dialogue spaces (chat-rooms). The users could thus conduct several conversations simultaneously, irrespective of the geographic and tactical location of their interlocutors. Within the same space, they participated in various dialogues, created collective dialogue spaces that facilitated group interaction and used private spaces to facilitate person-to-person exchanges (instant messaging). Most of the individual and collective dialogue spaces were secure, so users did not have to worry about espionage and piracy risks.

Naval Air Forces were familiar with the technical specificities of text-chat – during the operations in Afghanistan, each expert contributed on average to six dialogue spaces simultaneously – and they learned to exploit them. It is worth noting, for example, that users organized extended interest communities (navy, air and land forces) around the activities of most critical importance during offensive phases, namely meteorology, intelligence, logistics, air traffic control, oceanography and target designation. Each expert was actively involved in the dialogue with his or her community, while attentively following the neighboring conversations. Thus, users integrated in real time the new data and information exchanged in other spaces and which had a potential to affect their own planning.

Instant messaging, called whispering in the US Navy, has been used to conduct person-to-person dialogue. This additional activity allowed the user to search for information that was critical for the proper execution of a military operation, while avoiding overloading the collective conversation within the community. One expert got in contact with another by creating a dedicated personal space, obtained the requested information and then got back to the collective space to contribute to the conversation.

These text-chat uses facilitated the articulation of various communication practices (whispering and collective) starting from spaces organized as communities of interest, significantly improving coordination within and between teams of the coalition armies. This has been all the more true in the mission preparation phases. According to an intelligence officer: “Having a real-time dialogue with units of experts of the operational groups has simply allowed the tactical level to rapidly benefit from the analyses provided at our level”.

Before text-chat was implemented, the preferred communication technology was radio. The reception quality was not always guaranteed and users were frequently faced with difficulties in comprehending the oral messages (often due to limited vocabulary, accent problems, etc.). The act of radio communication could prove very time- and energy-consuming, reducing the drive to interact spontaneously and on a large scale. One of the text-chat contributions was to reduce noise during communication, allowing for text-based information exchange, which was more easily exploitable, particularly when the exchange involved multiple channels. An officer assigned to Task Force 50 (a US Navy combat group deployed at South of Afghanistan) noted: “Chat was awesome. Chat [was] like getting twenty new radios and being able to work them all at once”.

Thus, the very fact of using radio to transmit a piece of information or a directive came to have a particular meaning: it was a sign of a high-degree urgency or risk of unexpected event, when operators had no time to write and were forced to organize the mission through oral communication (“by voice”). Most of the time, users exploited text-chat and radio simultaneously. To the extent that each technology served well-defined objectives, it was not something that was forced on them, but something they had chosen.

Practices associated with the multiplication of sources of information were beneficial not only in the operation preparation phase, but also in their tactical execution. NATO Special Forces have developed communication practices for combat conducted deep in the territory. The situation differed in terms of bandwidth capacity, which was very low on the ground. War fighters found a way to bypass these limitations by connecting their laptops through the satellite connection for voice and text data transmission. Due to this “bricolage” [CIB 93], they could receive and send messages that were less elaborate than those exchanged within the professional communities in the preparation phases, but were accurate enough to allow for direct dialogue with the headquarters. The special units deployed in the Afghan villages developed interesting practices starting from this improvised text-chat. As they were positioned in proximity to the attack area, they first received a vocal message through the satellite radio requesting them to connect to their laptops. A precise order was sent asking them to go near a village where wanted individuals were hiding. The commando team confirmed good receipt of the order, and then opened a dialogue space with headquarters to discuss tactical details and ways to execute the mission. Complementary to this information, war fighters got used to opening other spaces that allowed them to collect tactical data from various sources. For example, the reconnaissance drones flying above these areas were displaying data from the ground (images, geographic coordinates, etc.) concerning the real-time evolution of the situation. The information essential to the offensive was very rapidly collected without the risk of misinterpretation. Once the mission was completed, a status report (number of prisoners, weapons found and intelligence gathered) was sent to headquarters, which then asked for details, if needed. The use of text-chat enacted by the Special Forces has significantly shortened the decision-making process. The capacity to follow the troops’ evolution in quasi-real time and to have access to continuously updated information has increased the responsiveness of headquarters, through reassignment of missions to those who were able to best respond to the needs on the ground.

3.1.2.2. Permanence of the flow of communication and persistence of information

In Afghanistan, text-chat was configured to allow for the reception and transmission of messages 24 hours a day. The permanence of the flow of communication was essential in the theater of operations, as missions had to be planned and executed anytime, by day or night. War fighters thus considered text-chat as one of the most reliable tools for command and execution: when the deployed units got so deep that they could not be reached by voice or when bandwidth capacities were not sufficient, text-chat became the only means of communication permanently available.

Little by little, the users took ownership of the capacity of permanence of technology and developed adapted communication practices: operators were still expecting to find an interlocutor to start a dialogue with. This expectation being shared by everyone, war fighters spent more and more time in front of their screens – up to 7 hours a day on average in the case of certain officers in charge of operating American aircraft carriers and destroyers during the first months of the war in Afghanistan. They were thus making sure they would never miss information that was important for the evolution of tactical plans. This behavior has led to a significant increase in the speed of mission planning and execution. As users exploited the permanence attached to text-chat more, their exchanges became more intense and strategic, and the incentive to stay in front of the screen grew stronger.

As an illustration, Task Force 50 implemented a planning and execution platform for Navy and Navy Air Force operations, named the Knowledge Wall. This platform provided access to various ICTs such as e-mail, Internet portal and evolutive databases. The additional information and knowledge thus collected have allowed an unprecedented level of precision to be reached in the analysis and processing of information for decision purposes. An air defense liaison officer aboard the USS Princeton noted: “The power of the system [Knowledge Wall] was in harnessing information from multiple sources, fusing it into a consistent, user-friendly format, and instantaneously disseminating that information back to war fighters and decision-makers”.

The Knowledge Wall and the radio constituted a portfolio of information and communication tools based on which the Special Forces developed communication practices that were adapted to the situations they faced. Mediated interactions effectively replaced face-to-face interactions, partly because individuals knew each other and shared standard action patterns, and because the time allocated to decision-making was very brief and they were not able to meet whenever they needed to. Face-to-face meetings continued to have an important role during more routine phases, such as mission debriefing, when actors could afford to take the time to comment and debate on their actions.

This articulation of technologies and uses has generated a debate about the problems of information overload. In effect, during real-time dialogues and information reception, the users had to pay continuous attention to be able to follow the evolution of the situation and to make sure they did not miss essential data. They then had difficulties determining when to stop collecting information and start focusing exclusively on mission execution. Furthermore, the multiplication of dialogue spaces tended to generate a surge in the volume of information to be urgently processed. There were times when users were flooded with information and had difficulties making a priority-based selection. Experimental researches conducted in the United States have revealed the difficulties in managing information flow [SCO 06] in the theater of operations. They have notably shown that in unexpected situations, where urgency and stress reach high levels, text-chat users tended to focus exclusively on the system interface. They were completely focused on processing demands and following dialogues, even as the instructor was trying to remind them of their main mission. Users learned with experience, however, how to take ownership of technologies and succeeded in giving them meaning in their specific work environment.

In this case, the American Navy forces have requested that text-chat be configured to show a guiding thread of conversations conducted in various dialogue spaces. A time-marking system has then been developed, giving authorized personnel access to a real history of conversations. As one user said: “The chat is better because it gives history, and you can watch things unfold in near-real time”. Special Forces also added a search engine to the system, and this allowed them to rapidly find, among multiple open or stored dialogue spaces, the fragments of conversations that helped them in dealing with such and such problem.

These additional capacities to store and search information conferred persistence to dialogue spaces. Users have also developed asynchronous communication practices, which were not initially planned for. Persistence of information has been considered an additional material feature of the permanence of flows and multiplicity of sources. Taken together, these features reduce communication costs and improve the coordination of teams in command and tactical situations.

3.1.2.3. ICT uses: combined communication practices

The examination of text-chat uses enacted in the theater of operations confirms the existence of links between the technical features of the tool, in particular its programming modes, and the context within which it is used. Actors have developed communication practices by articulating the interactive features offered by text-chat (synchronous communication) with the integrative decision-support features (history of conversations and databases). The sociomaterial characteristics of permanence and persistence attached to the tool have allowed for the articulation of these practices. For its part, the multiplication of sources of information has facilitated access to a broader variety of internal (such as logistics, ammunition, friends’ and enemies’ positions) and external (such as weather conditions, topographic elements and physical characteristics of the ground) knowledge. Without the multiplication of these sources, it is unlikely that users would have been able to implement uses that allowed them to exploit the variety of information and knowledge needed to conduct operations. In particular, the permanence of the flows of communication and the persistence of information were revealed and afterward reinforced through individual and collective practices aimed at integrating communication (interactive process) and decision-support (integrative process) functions into the daily uses of text-chat.

The case also shows that uses, as sources of communication improvement, combine with each other. These “combinations of uses” refer to a logic of assembly of the social–material features attached to a technological tool. These features are not perfectly embodied in the design of technology, as there is no upstream possibility for the designer to envisage the diversity of future uses. Some of these are enacted in situ by users during their interaction with technology in concrete work situations, between routine and unexpected situations, for example when creating a search engine that allows for useful information to be found rapidly: thus, text-chat supports the transmission of explicit knowledge within expert teams and communities. It is also the case when individuals go further into the interactive properties of text-chat associated with the permanence of information channels and the multiplicity of sources, in order to improve communication and team coordination during the mission planning phases. Here, text-chat supports the transmission of experience and the sharing of more tacit knowledge among actors.

When unforeseen situations require the accomplishment of new tasks, technological uses and their combinations improve the dynamics of coordination. Field results are a good illustration, as they refer to the actors’ capacity to get involved in multiple opportunities for horizontal communication. Collective procedures for problem resolution are thus being reinforced. Decision structures are more decentralized and hierarchical authorities can concentrate on key decision-making phases. The new communication practices also have a tendency to modify the temporality of the relations among actors and to improve their awareness of the shared situation.

3.1.3. Communication practices: a synthesis

The examination of communication practices based on military illustrations highlights the crucial role they play in team coordination in the extreme environment. Practices based on common languages first improve the transmission and comprehension of messages exchanged by the actors, thus reducing the risk of misinterpretation. This is because through training and missions they become automatisms. The time they help gain can be used for the analysis of unexpected situations and collective sense-making. Finally, combined technological uses stimulate the emergence of innovative communication practices, adapted to the constraints and opportunities of the action environment (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1. Communication practices

| Shared languages | Code words, diagrams and drawings, gestures and body expressions |

| Combined technological uses | Individual and collective exchanges, explicit and experiential knowledge, real-time information, history of information exchanges |

3.2. Reflexive practices

The study of team coordination in the extreme environment reveals the existence of a second category of practices: reflexive practices. Reflexivity evokes an individual or collective capacity to call into question interpretations and completed actions. It is a matter of standing back and examining successes and failures in order to identify the best ways of individual and collective functioning and find effective problem resolution processes. Reflexive practices are thus based on calling into question, debate and consensual search for solutions.

In the military, reflexive practices develop mainly during debriefing sessions [GOD 12a]. The following case proposes to describe debriefing as it is conducted by the French Air Forces squadrons (taking all fields together: fighter forces, transportation and presentation).

3.2.1. Briefing–debriefing in the French Air Forces squadrons

A working day in a squadron always starts with a general briefing of 30 min attended by all the pilots, navigators and trainees who have one or more flights scheduled. After this general briefing, the navigating personnel divides into patrols or crews of two to four members who participate in a briefing dedicated to the flight(s) they are assigned to. Immediately after the flight, they get together for the mission debriefing which lasts between 40 and 45 min.

Debriefing sessions are very formal and follow standardized procedures (NATO manual). They consist of taking in reverse order the points discussed during the briefing, with a stress on flight security. Certain fighter squadrons have flight reconstruction systems that digitize the aircraft flight path. As regards the display teams such as the PAF and the AFAT, they are always accompanied by a cameraman who films the flights and then provides the pilots with the digitized videotape. Thus, pilots have access to a clear representation of the training and exercises performed during flight and are able to accurately evaluate the quality of the mission. Each flight comes under scrutiny, particular attention being given to inappropriate actions (errors), their causes and the solutions that might be implemented. Errors that occurred during flight may be considered serious or less serious. An error can, for example, relate to a breach of flight security rules (always covered during the briefing), such as low altitude flight over a residential area; but it can also be a pilot’s error that may endanger his/her or his/her teammate’s aircraft and lead to an incident or accident. These are highly tense moments during debriefing, as the critique, usually severe and abrupt, is public. Finally, trainee pilots are under additional pressure, as they are evaluated by their trainer, who issues a formal progress report.

3.2.2. Reflexive practices in debriefing sessions

3.2.2.1. Learning from errors, by experimentation and from others

When asked “what are in your opinion the main objectives of briefing–debriefing?”, all the personnel interviewed answered: to facilitate learning and individual progress on one hand, and to permit collective improvement, on the other hand.

Pilots are systematically evaluated by their colleagues and/or hierarchy (in the case of trainee pilots) and can be disciplined in case of failure (bad decision, breach of flight security procedures, etc.). As a fighter pilot states: “The main interest of debriefing is to improve. Debriefing provides the opportunity to analyze what was done effectively or ineffectively and to find solutions to what was perhaps done less effectively during flight, through dispassionate analysis of what happened, so that solutions are readily available next time”. Each member of the navigating personnel agrees on this elementary function of debriefing and considers that error detection and correction are the best ways to progress and become successful.

While trainee pilots are particularly concerned, seniors are also interested in this process. They willingly admit that even the most experienced and talented pilots are no less exposed to error and may benefit from peers’ comments and remarks. Several interviewees noted that critical examination of the actions during flight was the very essence of debriefing. One of them explained: “Debriefing focuses essentially on finding out what happened during mission. Precisely. Why? Because during flight things go too fast. One needs to trace back, almost like a historian, what has really happened and then understand why it happened that way in order to learn and eventually progress”. This error detection and correction approach presupposes actors sharing a certain number of prerequisites, in particular: observing others’ errors is an opportunity for self-correction and the presence of other colleagues during debriefing not only guarantees all the errors are spotted, but also permits us to envisage a complete panel of solutions/corrections.

Sharing these prerequisites facilitates the implementation of a constructive process, through which one’s own practices improve due to others’ critiques and comments. This learning from error process is based on daily experimentation. As one of the display teams’ pilots states: “What we do is pure flight, and sensations are essential. In the case of a problem, you don’t search a database to find the answer! Theoretical knowledge is good… but it has no value unless it is put into practice”. The error correction approach, either for errors during flight or for those on the ground (for mechanics), is marked by the experiential nature of the knowledge it transmits. The display squadrons push this logic of experimentation to the extreme, bringing their bodies into it. As we have previously mentioned, pilots rehearse their flight before taking command of their aircraft. Keeping their eyes shut, they express with their hands and bodies the sequence of figures and aerobatic maneuvers they will present during the show. This “music” (for PAF) translates each of the technical gestures learned, criticized and learned once again during the debriefing sessions. It is also a moment of deep concentration that acts as a catalyst for emotions – such as stress – and permits the bodily and sensory preparation of the pilots for flight.

Debriefing also contributes to team progress. In effect, pilots and navigators insist that error detection/confrontation and the capacity to learn lessons at an individual level reflect on the group. Whether they are navigating personnel or not (for example, mechanics), the essential thing is that they participate in mission preparation and execution. A transport pilot explains: “The ultimate goal is to progress, get better. And I say get better in this impersonal manner because it concerns everyone, all the participants: controllers, pilots, navigators, crews, mechanics. All the actors involved in the mission have the same goal: progress. Debriefing should lead to individual or group learning so that next time the machine becomes even more successful. I use the term machine in the broad sense, as a complex system of all the individuals”. Each mission is an opportunity to learn and experiment. As they agree to work in a constructive criticism mode, all personnel members approach debriefing as a multilevel learning process that contributes to the progress of the person both as an individual and as a member of a team. A fighter pilot insists: “Debriefing permits us to once again prepare to perform as we should next time. It is part of a whole process. So debriefing as such… We shouldn’t take it out of context. We are working within this logic of success: we have to learn the lessons that will permit us to be successful, both as a group and as individuals. The lessons learnt during debriefing will strengthen both our global and individual knowledge. It is not an exercise in style, we are learning to be present at the right moment, when the day will come”.

According to the personnel interviewed, this shared view on error as an opportunity for individual and collective learning relies on a principle that was institutionalized within the French Air Force: error is not punished. Since 2006, it has been officially enforced by the French Air Force Chief of Staff: “We should agree to systematically account for our errors, to comment on and inform our peers about all the near-miss incidents on the ground or during flight, all those events that ‘nearly happened’. Our whole community should be able to take advantage, for learning purposes, of all our experiences, disagreeable as they may be” (source: French Ministry of Defense). Within this framework, pilots engage a posteriori in institutionalized learning practices, governed by the rules of transparency and error recognition.

3.2.2.2. Artifacts for confronting one’s errors and interacting with others

The analysis of data highlights the role played by technologies. For example, the use of flight reconstruction systems by fighter squadrons permits pilots to be systematically and objectively confronted with reality: watching the flight recording helps them accurately represent the mission unfolding and the eventual failures. Other squadrons, such as the display teams, have a cameraman at their disposal who films each of the flights and then makes them available to the pilots: “Once he gets off his aircraft, the pilot can watch the recording of the entire flight. During the flight, I [another pilot from the team] am next to the cameraman and all the comments and critiques that I make are recorded. When the pilot finishes his flight, he listens to these comments, while watching the film. He scrutinizes his performance, notices his errors, but he needs to be equally aware of what he did well. He needs to understand why he was successful with that figure or why he failed it. He needs to be aware of his state of mind during those moments”. The facts are clear, transparency is the rule and each participant needs to be ready to accept full responsibility for his (or her) errors.

In this respect, technologies have to a certain extent revolutionized the briefing–debriefing procedures in as much as, before their introduction, some experienced pilots may have been inclined to underestimate the importance of their errors. A navigator from a transport squadron indicates: “In the past, it was very easy for a senior [pilot] to say that he had done this or that, that he was in the best position etc. And in the end, even though he may have had his doubts, the young trainee took the senior’s word as a reference, because he was the strongest, or at least he spoke the loudest. But the reconstruction system provided all those people with an opportunity to call themselves into question. And this is a good thing”. Allowing pilots and navigators to examine the objective flight data, flight reconstruction systems and films facilitate control and confront them with reality. As a fighter pilot explains, everyone, when confronted with his or her flight, needs to be able to precisely describe the problems he or she faced, to explain the reasons that led him or her to make the error and to derive from the incident the lessons for his or her next flight. The pilot states: “We all know, even those of us [who are] more experienced, that errors are nothing else but opportunities to learn. As far as I’m concerned, the moments that have most strongly marked my professional life were those when I made mistakes that I was sharply made aware of during debriefing, videotapes being there! I have not repeated those errors since then, and they marked me to the point where I still think about them”.

One of the French Air Forces display teams in 2012 implemented a camera device in the cockpit of its aircraft. It is usually directed toward the pilot’s legs and/or hands. The objective is to access how things are done in a situation. All the pilots are present during viewing so that they can observe technical errors, sources of problems (even incident/accident) during flight and good gesture and visual practices, which are sources of success. It is a group debriefing on one pilot’s performance. As one of the pilots explains: “When watching these internal films, we notice the way in which he [the colleague] flies. For example, the visual circuit is very important in aerobatics, and often pilots do not know where to look. There is a delay in the visual circuit, which leads to the wrong activation of their movements, in a hasty manner. Having one or two seconds advance over their visual circuit would be enough for them to see the objective coming and to activate with more liveliness. With the internal camera, one can understand why anticipation is wrongly operated”.

Video-based debriefing is deliberately directed toward team progression not only in technical terms, but also in collective terms. It is a matter of building synergy in the group, facilitating mutual learning through others’ practices. One of the pilots interviewed insists: “Criticism may sometimes be heavy during the debriefing of the internal video, but we need to know how to encourage ourselves. Everything must be done in a constructive spirit. If this is not the case, then it’s useless, the group is no good and the results are worthless”. It is a matter of sharing know-how and being willing to ensure the team evolves as a whole. The pilot adds: “The group relies on a somewhat particular type of equilibrium: there is a very individualistic spirit of competition, and each of us wants to be the best. Then there is a team spirit, which is essential to survival in the squadron, in the team. It is in this sense that the [internal] video plays its role. It shows one’s know-how and it helps communicate one’s ‘tricks’ and continue to progress as a group. The dissemination of practices, ways to succeed in performing such and such figure, the errors to avoid… all these are balanced during the video debriefing”.

3.2.2.3. Adopting a critical stance

The great majority of the interviewees think that debriefing sessions rely on and enhance personal qualities and attitudes. The most frequently named were modesty and calling oneself into question. Pilots and navigators define modesty as a capacity to admit one’s errors and assume full responsibility: “Being alone in the aircraft is one thing, debriefing in front of the other pilots, peers, even in front of the squadron when there are concerns related to flight security is something else. It means assuming responsibility in front of everyone. One has to take responsibility. We need to debrief in order to progress and it is also a means to remain modest in one’s work”. As a pilot of one of the display teams notes, modesty is certainly a personal predisposition, but it can also be acquired during debriefings: “They say that the first year is the toughest, because we are effectively ‘torn apart’: there is a lot of criticism, but it is constructive, as the aim is to become aware of our errors and to progress. All this may sometimes be too intense because obviously not all our flights are perfect, far from it!”.

Modesty is closely linked to calling oneself into question. A former leader of the PAF explains: “Debriefing is directly associated with self-analysis. It is crucial for a leader to be able to admit his errors and call himself into question. When I saw that for three flights in a row my inside right [first year in the Patrouille, evolving on the leader’s right side] did not manage to execute such and such figure, I said to myself that I was to blame too, simply because I served as a point of reference to him! What did this mean? I needed to permanently call myself into question. Being a leader doesn’t mean that you know everything. On the contrary, you discover quite a lot of things. Even when you have a certain background, real experience, you have to be able to analyze and call yourself into question”. Debriefing sessions imply that navigating personnel is able to admit errors and to assume responsibility so that he or she avoids repeating them during future flights.

3.2.3. Reflexive practices: a synthesis

To coordinate in an extreme environment, teams need to be reflexive. This means that their members are able to question their actions and call themselves into question when faced with individual and collective errors committed during mission and project execution.

During dedicated sessions (such as debriefing for military teams), individuals examine what happens (or what happened), why it happens (or happened) and draw lessons in terms of individual progress, collective performance and evolution of their functioning modes. The learning cycle thus depends on the capacity of actors, teams and organizations to continuously advance in the execution of future projects, starting from the analysis of past experiences and errors (Table 3.2). The role of the organization should not be neglected: it is in a position to support and even to institutionalize, as in the above-mentioned case (error is not punished in the French Air Force), reflexive practices developed by the teams.

Table 3.2. Reflexive practices

| Learning | Starting from: one’s own and other’ errors, others’ success and know-how, one’s own and others’ experiences |

| Technological and videeo artifacts uses | Confrontation with errors, critical and constructive discussions |

| Critical individual and collective stances | Modesty, calling into question, accountability |

3.3. Socialization practices

The third and last category of coordination practices developed by teams in the extreme environment relates to the socialization process. It is a noticeable fact that actors have a need to interact, exchange and more generally get to know and trust each other in order to be able to effectively manage the shift between unexpected and routine situations. In the French Air Force squadrons, such processes emerge and unfold mainly in a dedicated space: the squadron bar.

3.3.1. The squadron bar: where common knowledge is built

The squadron bar is intended to be a welcoming and friendly space (Figures 3.5(a) and (b)). It is often decorated with items that reflect squadron life: models, sketches and/or drawings of the main aircraft and its technical evolutions, books or magazines about the squadron, its history and news, squadron patches and other patches left by visiting pilots, photos of the teams in theaters of operations, during demonstrations or training, etc.

Figure 3.5. Example of a squadron bar in Cambrai, Air Base 103 Cambrai-Epinoy (source: www.aviation-illustree.forumactif.com)

The squadron bar is often seen as an opportunity to socialize by the more senior personnel (pilots, navigators and mechanics), and as a means to integrate the professional community and the teams by the junior personnel. In the morning, during coffee time, or in the evening, after the missions, they freely discuss their day, the pressure they felt, the situations they have experienced and solutions they found to avoid or solve problems. These discussions frequently have a humorous tone: little mockeries, jokes and familiarities are the main carriers of the messages exchanged by team members. The atmosphere is relaxed, friendly. As a mechanic of the AFAT states: “We need to find opportunities to discuss in a more relaxed, less formal way [than during the debriefing sessions]. The squadron bar is essential as a friendly space for discussion and debriefing. We still discuss the mission, but differently, sharing experiences and taking a step back from what has just happened. It is an opportunity to know each other beyond our technical capacities and expertise, to better understand each other’s personality, attitudes. It is also an opportunity to build a team spirit”. The squadron bar is, therefore, a space where team members get together and discuss their recent experiences – things that happened during the latest performance and need to share with the others so that overall performance improves – as well as past experiences – individual or collective anecdotes that remind team members to avoid committing the same errors. The dynamics of the informal exchange of experiences generates results that are all the more interesting if all professions and specializations have access to these spaces. Team performance is the result of proper integration of knowledge and expertise brought by all team members. Group consensus results from the inclusion of various points of view, experiences and perspectives.

These discussions and exchanges of experiences contribute to the progressive building of a common knowledge stock that permits individuals to gain shared comprehension of the foundations and practices of the profession. A transport pilot explains: “I think that the squadron bar contributes to collecting knowledge, old stories, comments. There is a way of doing things. In aeronautics, even in the military, there is a global way. And this is so complex that one has only a vague idea at the beginning. So it is worth being at the bar and finding out what happened from people who were there. Who landed in such and such areas. One learns about the missiles, a way of doing things. A sense of break in order to land. There are no limits”.

The French Air Force personnel seek to develop common knowledge as they are aware that it is the basis of all collective work in unexpected situations. As a navigator notes: “There is however one sine qua non condition for effectiveness, especially when managing extreme cases; it is the mutual knowledge within crews”. Mutual knowledge refers not only to reciprocal knowledge of team members, but also to tacit knowledge referring to the capacity of the team to manage the shift between routine and unforeseen situations. In order to develop this type of knowledge, personnel feels the need to get together and interact. A FAC notes: “Interpersonal skills are part of the profession. You must be curious to go and see the pilots, to know their procedures in order to be in line with what they are doing and effectively meet their needs”.

3.3.2. Cohesive activities that convey team values and build mutual trust

These informal discussions at the squadron bar sustain a structured and democratic system based on which participants share and disseminate the team values and, in a broader sense, those of the squadron. These values are first acquired during the initial training, before assimilation in operational squadrons, and end up becoming second nature for the navigating personnel. In particular, they produce “facilitating” collective devices such as social control, mutual trust and cohesion. A fighter pilot notes: “The squadron bar also offers the opportunity to build trust. Someone may be a very good professional, but behave deplorably on the ground, not knowing how to behave though he feels in his place during flight… Such a person does not have what it takes to be a good pilot. This is where education and growth play their part. It is a whole. In its area of responsibility, debriefing means preparing coffee in the morning, knowing how to listen etc. It is professional and extra-professional progress”.

Team values are also disseminated through traditions. The latter embody the feeling of being part of a squadron, while participating in building a unique team and advancing in the same direction. One pilot from PAF explains: “Cohesion is for me the keystone of collective synergy and trust. And traditions play an important role. The aim is to bring people together. And bring them to identify with those common values and principles. This is the role of traditions that were passed on to us by our elders. Traditions spice up the team spirit and consequently reinforce synergy. There are little traditions throughout the year. For example, the loop of eight jets [when the eight pilots of the PAF synchronize to perform a loop]: the first successful loop of eight is the moment when the three pilots having most recently joined the PAF receive their badge. In general, this is also the moment when they have their helmets painted”.

In the squadrons, besides tradition-related entertainment, there are also other so-called “cohesive” activities. In this context, sports play a central role. Basketball and football matches, muscle-building sessions, trips to the mountains for skiing (for example, PAF annually organizes a week of skiing for its members) or hiking are all opportunities to get to know each other outside of the professional environment. The objective is to facilitate gradual building of trust among actors.

It is worth noting that in the extreme environment, where actors may be under high levels of tension and stress, mutual trust is essential: everyone’s survival depends on everyone else’s quality of work. There is no place for doubting others’ competences, as all teammates need to fully focus on task execution and progress. One pilot notes: “Trust guarantees mutual protection”. Another one goes even further, referring to collective performance: “With Captain X in charge, we will fly and be effective. What makes this result possible? The fact that we have known each other for quite some time. We have mutual knowledge and we trust each other”. Mutual trust acts as a catalyst for emotions and stress within teams. This required trust develops and perpetuates partly through the texture of social relations built by the actors. The navigating personnel cultivate these relations. Aviation culture (for example, flying two-seat fighter jets such as Mirage 2000, or tactical transport aircraft with two-to-four-member crews) and the habits of living in a squadron are privileged ways for building and strengthening mutual trust. A navigator states: “Squadron is a tribe. Trust is part of our culture”.

Moreover, when military teams leave for the theater of operations, they are most often already “constituted” meaning that they will always work together: team composition will not change during the mission. A pilot explains: “When we leave in constituted detachment, the patrols [two fighter jets] are made and the pair is never mixed”. This contributes to building trust as everyone sets to know and appreciate the other’s way of doing things, his or her reactivity, capacity to adapt and make decisions. For example, referring to the relations between FACs and Mirage 2000D crews in Afghanistan, a controller notes: “The fact that FACs are in the proximity of squadrons is essential. It helps them cover their aviation culture gaps. Moreover, crews have an opportunity to trust the FAC”.

3.3.3. Socialization practices: a synthesis

To be able to manage sudden shifts to unexpected situations, teams need to know and trust each other. To this end, they develop socialization practices of various natures (Table 3.3).

The illustrations show in particular the central role played by spaces dedicated to socialization. They are shelters where close relationships between the actors are gradually built, in an atmosphere of proximity and familiarity. Taking ownership of these spaces (for example, through arrangement and decoration) is part of the teams’ participation in building common knowledge and trust. Moreover, team values are disseminated through everyone’s involvement in cohesion activities, such as sports and other activities related to traditions and collective history.

Table 3.3. Socialization practices

| Taking ownership of spaces | Dedicated spaces, decorations and arrangement, regular presence |

| Open discussions | Mockeries and jokes, “talk straight”, stories and exchanges of experiences |

| Commitment and perpetuation of team values | Individual and team sports, respect of traditions, team outings |

3.4. Coordination in the extreme environment: articulation of communication, reflexive and socialization practices

In a rapidly changing context, where the probability of occurrence of an unforeseen event is strong and the risk to life is high, actors are in search of updated knowledge related to the specificity of their tasks within the team, on one hand, and the means to accomplish them, on the other hand. Opening new analysis perspectives, and complementing the more structural view of contingency theories, the practice-based approach offers elements enabling us to understand how teams cope with these challenges. By facilitating the examination of in-situation production of coordination, this approach permits the discovery of a set of practices and uses that the actors build and develop on a daily basis in order to stay successful when faced with unexpected situations.

The examination of military cases first permits us to highlight the role played by communication in coordination. The practices of common languages and innovative technological uses permit us to sort out pertinent from less pertinent information when in action. Being based on a set of code words, diagrams and modes of body expression, languages evoke many common references for the teams to rely on for comprehension and exchange. They translate modes of expression and automated reasoning that are shared by all the team members: a set of technical, identity-related (languages make sense within the team and more broadly within the professional community) and social (activated to manage actors’ interactions) references. The combined uses of technologies made available to the actors in turn facilitate the adequacy between the technical capabilities offered by the tools and users’ needs in the field. In this sense, communication practices permit individuals to save time they can dedicate to sense-making and finding solutions to more complex, because unexpected, problems. They also facilitate collective rooting by feeding the identity and social dimension of the group.

Reflexive practices represent ways to learn from individual and collective errors and calling into question common action patterns. These practices unfold in time: frequent iterations on team errors and successes encourage the adoption of a sustainable critical stance, which can even be institutionalized, as in the above-mentioned case of the French Air Force. More precisely, the calling into question of team modes of functioning and individual stances stimulates the emergence of long-lasting values at the group and organization level. In that respect, reflexive practices play a key role in coordination: on the one hand, they lead the actors to reflect on the approach of this and that situation, and on the sense they give to it; on the other hand, they direct them toward problem-solving methods that are based on calling into question, debate and seeking consensus.

Finally, socialization practices highlight the importance of human relations, cohesive activities and traditions for coordination in extreme environment. Proximity is essential to the extent that it allows the actors to assimilate and perpetuate team values. These aspects are closely linked to reflexive practices. In effect, the learning processes implemented by the actors, admitting one’s errors and learning the lessons applicable on average/in the long term, may exert high social pressure. In this context, they are not viable unless the team has a constructive approach. It has nothing to do with accusing an individual, excluding him/her or neglecting collective responsibilities; on the contrary, it is about generating an internal dynamics capable of sustaining reflexive practices. From this perspective, spaces dedicated to connecting team members are a guarantee of successful integration of experiential knowledge into a common knowledge, and gradual building of mutual trust.

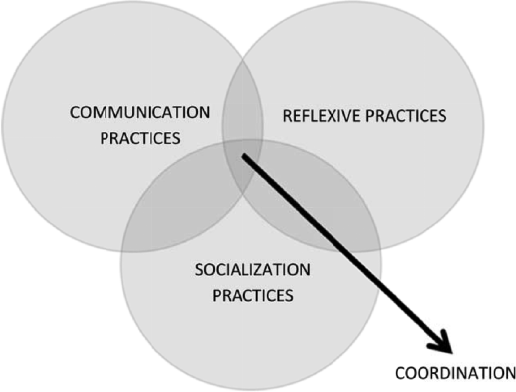

Team coordination in the extreme environment is based on the articulation of communication, reflexive and socialization practices (Figure 3.6). It is in this articulation that a team’s capacity to manage frequent shifts between routine and unexpected situations resides: it facilitates the production of consensual interpretation of situations, by making and preserving sense.

These results contradict others that claim in particular that standardization and automation of communication practices are sufficient for coordination. It is in particular the case of professional works and norms that insist on the individuals’ capacity to achieve a collective result on the basis of highly standardized actions/reactions. For example, the contributions of Hutchins [HUT 95], Hutchins and Klausen [HUT 96] and Hutchins and Palen [HUT 97] on crew coordination during flight on commercial airliners seek to demonstrate that an automated structure such as the cockpit “system” is in itself supporting coordination between pilots. Their interactions being highly standardized, pilots use highly predictable action patterns, multiple tasks being thus automated. According to the authors, these elements favor a level of interchangeability of crew members, who would have no need to know each other to be able to coordinate, the knowledge of the cockpit “system” functioning being sufficient [HUT 96].

While our field results confirm the standardized and automated nature of certain communication practices, they tend to invalidate the idea of interchangeability as applicable to coordination in the extreme environment. In such circumstances, teams are faced with unexpected situations whose causes are often exogenous to the “system” itself. They have to adapt in real time. The fact that they know and trust each other and that they are used to critical reasoning, calling into question their perceptions and problem-solving modes, allows them to save precious time to interpret the situation, give it sense and explore new solutions. The actors rely to the same extent on emotional and social bonds developed in time, as on the formal framework within which activities are carried out and on “system”-distributed knowledge. Could it be that the crew of Rio–Paris flight lacked this dimension? The question is open to debate.

Figure 3.6. Articulation of team coordination practices in the extreme environment

Team coordination in the extreme environment thus requires the implementation of conditions that contribute to the building and sustaining of three categories of coordination practices and their articulation. Chapter 4 examines the following question: what managerial conditions should be provided to support team coordination? How can decision-makers be guided in adopting directions and making managerial choices?