CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCING BUSINESS CONTINUITY MANAGEMENT

What is business continuity management?

Business continuity management (BCM), or business continuity (BC) as it is more commonly named, is essentially a form of risk management that deals with the risk of business activities, or processes, being interrupted by external factors, as distinct from business or commercial risks, such as, for example, the loss of a supplier or foreign exchange losses.

All organisations conduct risk management in connection with many, or even all, of their activities; however, this is often done intuitively and is unlikely to cover all aspects of the organisation’s operations.

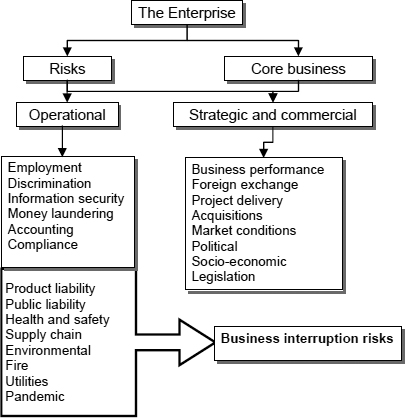

Organisations of all types carry a variety of risks, both operational and strategic.

Figure 1 shows some examples of business interruption and continuity risks in the context of the overall risk spectrum.

Later in this book, we will look at the scope of business continuity, and how certain risks, or scenarios, may fall within, or outside that scope, depending upon the individual organisation’s policy.

Figure 1: Business interruption and continuity risks

Evolution

Business continuity management really evolved from the older discipline of Information Technology Disaster Recovery (ITDR), during a time when systematic approaches to business management were becoming increasingly popular. This coincided, to some extent, with the growth of corporate governance standards which included a significant focus upon the management of risk.

During the late 1970s and 1980s, as computers were introduced to many business processes, their relative unreliability, and the potential to lose all of the organisation’s critical information in one go, revealed the need for methods of backing up and retrieving data, and the computer systems themselves.

The ITDR industry has, since the late 1970s, become very well established, and it is now unthinkable for almost any organisation to have no data or hardware back-up and recovery arrangements.

As modes of doing business expanded rapidly during the 1980s and 1990s, and as previously unthinkable incidents started to have a real impact on businesses and other organisations, the discipline of ‘business continuity’ evolved as a way of minimising the impact of any operational interruption that might occur.

The new business of corporate governance also began making it necessary for boards to ensure that risk control measures generally were much more systematic. They needed to be commensurate with the risks they addressed, and to be documented so that the organisation’s preparedness could be properly audited and assessed, and so that, in the event of a real incident, it could be shown that the organisation had taken appropriate steps to minimise impact and protect the interests of its stakeholders.

The growth of the business continuity industry was arguably led by the financial services sector (particularly the larger banking institutions) which is regulated by the Financial Services Authority (FSA) in the United Kingdom, the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) in the United States, and by similar regulatory bodies in the vast majority of developed countries around the world. Whilst the UK’s Financial Services Act itself does not stipulate a requirement for regulated firms to ‘do’ business continuity management, the FSA’s Business Continuity Management Practice Guide makes it clear to those firms that they are expected to have a business continuity management system based upon good practice principles.

In the US, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, contrary to the claims of some practitioners, again does not expressly require firms to have BCM arrangements in place, and here, as in many other similar pieces of legislation around the world, there is likely to be some form of implicit requirement to manage and control operational risks, which must include operational interruptions.

As one would expect, the reliance of many firms within the financial services sector on large information systems operating on very short time scales, dealing with banking transactions and the like, has meant that they had to ensure a high level of ITDR capability. It therefore became a natural extension of this management discipline to put similar arrangements in place for all other operational aspects of the business.

The Business Continuity Institute (BCI) was established in 1994 by a number of business continuity practitioners, many of whom were IT professionals working in the financial services sector. Also during the 1990s, the British Standards Institution (BSI) published a document called Publicly Available Specification 56 (PAS56), which attempted to set out a methodical approach to business continuity.

PAS56 was superseded by BS25999 in 2007, but it was, for some time, the only standard guide to business continuity management.

These developments have all contributed to the growth of a discernible business continuity industry which comprises a wide variety of in-house practitioners, contingency resource providers, software tool developers and out-sourced professional service providers, helping many organisations to rapidly establish a fit-for-purpose system.

The differences between PAS56 and BS25999 were very significant, and the latter did a good job of establishing a sensible framework for how organisations might go about ‘systemising’ their arrangements for operational resilience and responding to incidents.

The differences between BS25999 and ISO22301 are arguably less significant; many of the changes are more to do with fitting the ISO standard format, but there are also some which simplify the requirements, are more logical, and remove some of the jargon that is not always seen as helpful.

Most significantly, any organisation that is already developing other management systems, or has them in place, should find that a business continuity management system developed under ISO22301 is much easier to integrate with others.

The business continuity management system (BCMS)

Business continuity is really a contingent discipline that is only required in the event of an interruption. It could be likened to a car driver having a subscription to a vehicle breakdown assistance service. If that driver did not know how to contact the service, or did not know under which circumstances the service could be invoked, then its value would be very much reduced.

Similarly, with business continuity, the organisation that has experienced an interruption may need to invoke alternative resources to enable it to resume its operational activities. If it is to achieve this, the right information and the right resources must be available.

Here, the distinction between business continuity (BC) and disaster recovery (DR) is important. The principal instrument of BC is the BC plan (BCP); the tool that guides the organisation’s management in responding to, and recovering from, an interruption, in the best possible way. However, the BCP will only be effective if the DR resources that it cites are actually available, and provide the functions and capacity that the plan expects.

Good practice in business continuity management today is about being able to deal with a wide range of interruption scenarios, having contingency resources that are commensurate with the business processes they support, having effective documented plans that will work because they are ‘owned’ by the organisation and kept up to date, and having a capable team of people who can lead the organisation’s response and recovery.

This good practice can be delivered by a systematic approach that is enshrined within ISO22301:2012 Societal security – Business continuity management systems – Requirements.

This book provides practical, detailed guidance on all the steps necessary for an organisation to develop, and implement, a business continuity management system that is capable of certification to this standard.

The relationship between business continuity and disaster recovery

In reality, the terms ‘business continuity’ and ‘disaster recovery’ are interchangeable. The result of doing disaster recovery properly is that the business (or other organisation) resumes what it was doing before being interrupted – in other words, that it continues. ‘Business continuity’ was introduced as a way of differentiating something that just restored computer systems and data, from something that restored business processes and entire organisations.

It is really just a matter of evolution that ‘disaster recovery’ has come to mean arrangements for replacing resources, whereas ‘business continuity’ has come to mean a broader, management discipline, including planning and DR, which should ensure the continued operation of an organisation following some interruption.

As previously mentioned, the ITDR industry is probably the most mature part of the BCM world, but IT or ICT (Information Communications Technology) is only part of the resource base for any organisation. Chapter 4 of this book looks in some detail at what is referred to as ‘BC strategy’, that is, deciding how the operational resources upon which the organisation depends, will be both protected from threats, and replaced in the event they are disabled.

So, DR is really about all the organisation’s operational resources, not just the IT or ICT systems, and this area is also frequently referred to as ‘resilience’. That title, of course, implies that the resource in question will not fail in the first place.

An obvious example for explaining this terminology is the typical IT system in Example 1, below.

Example 1: Failover resilience

A company with a local area network (LAN) in its offices might invest in a ‘failover’ facility. This means that, should the server that provides the company’s staff with applications and data fail, another server will, often automatically, take the place of the failed server, so that the staff can continue doing their jobs.

This is resilience of the IT applications (and their associated data), but it is provided by what is known as a DR service, which might also be employed in the event that the company’s entire office building was destroyed.

Disaster recovery can, and often does, exist on its own. However, it is also an essential component in BCM, because it provides the necessary resources that enable business processes to be executed, when required. It should also be noted that DR does not, itself, include any proactive risk management, and, whilst the selection of DR arrangements is sometimes based upon a risk assessment, it is perhaps more often based upon an intuitive understanding of what resilience or contingencies are required.

Cause and effect

There are many reasons why an organisation’s normal activities could be interrupted, and whilst cause, or threat, is an important part of risk assessment and the development of resilience, much of BCM is about effect. The impact of an activity being interrupted should be more or less the same, whether the interruption is caused by a fire, a terrorist act, global warming or pandemic flu.

This distinction actually makes the BCM practitioner’s life a bit simpler, not least because many plans and response mechanisms can be ‘universal’, focusing on restoring only the interrupted activity.

That said, there is definitely a place for scenario-based plans, but, as we shall see, these, again, can encompass a range of causes or threats, so that the overall arrangements may be as simple as possible.

BCM policy

What is policy?

BCM policy is something that has escaped many organisations attempting to put a sensible BCM system in place, usually because there has been no clear idea of what such a policy should be.

The real purpose of having a BCM policy is to ensure consistency and objectivity in the way that different parts of an organisation are protected by the various measures that the BCMS involves. It can also help to optimise the resourcing of BCM by, for example, defining the scope of what parts of the organisation are to be covered by the protection of BCM, so that one, low value activity, does not receive more protection than another activity of higher value.

In some organisations the policy can be useful in securing collaboration. Not everybody wants to get involved in BCM straight away, and sometimes the existence of a policy – a statement of requirement from the Board – can help in getting people behind the project, and the work that needs to be done.

Policy can also be useful as a form of corporate assurance. When a legitimate, interested party, such as a customer, wants assuring that one of their suppliers won’t let them down, a written policy can often be more useful than a verbal assurance, especially when the former is much more likely to be supported by real resilience arrangements.

These objectives should be met by a written policy document that includes, inter alia, the elements below.

- A statement of intent, purpose, objectives and any external compliance requirements for BCM; the policy statement.

- Scope – this may specify parts, or aspects of the organisation, that are to be included, or excluded, from the BCMS, such as:

- Business units or divisions

- Types of business process

- Financial values

- Geographic or other territories

- Types of risk; physical, internal/external, strategic, financial, etc.

- Criteria for measuring and assessing impact, and the likelihood of threats materialising.

- Classification of risks, such as: acceptable, tolerable and intolerable.

- Rules for controlling (mitigating) and monitoring risks in different classifications, including timescales, where relevant.

- Assignment of responsibilities and parameters for developing, maintaining and testing the BCMS.

- A process for providing assurance to the Board or governing body, as to the adequacy of the controls in place for business interruption, and other risks that fall within the scope of the policy, and the plans and resources that effectively constitute those controls.

It is likely to make sense for most organisations that the policy serves as both an internal document and an external one, available to legitimate scrutineers who need to be satisfied that the organisation’s business-interruption and similar risks are adequately controlled; and that it has taken all reasonable steps to ensure its continued operation and survival in the event of an unforeseen interruptive incident of significant proportions.

Although most of the key elements in the policy are described in greater detail throughout this book, the items below should also be considered.

The policy statement

Every organisation will be ‘doing’ BCM for its own reasons. These should be included in the policy statement, in a way that will make sense to all its audiences. The commitment to developing, implementing and maintaining a BCMS is important in any organisation:

- For employees, because it gives them an additional level of confidence in their employer’s resilience.

- For managers, because it provides a mandate to engage in activities that contribute to development and maintenance of the BCMS, and effectively to use the organisation’s resources in so doing.

- For customers and clients, because it provides additional assurance as to the resilience of their supplier; an element in the due diligence process.

- For suppliers, because it provides greater confidence in the robustness of their markets, particularly where the organisation is a major customer to any supplier.

The policy statement is also a good place to set out the objectives – more specific and measurable targets that represent the key benefits for the organisation in developing a BCMS. In some cases, it may be appropriate to develop key performance indicators (KPIs) from these objectives, the achievement of which is likely to mean that the objectives are being met. As we’ll see later, amongst these KPIs are likely to be the regular and comprehensive review and updating of the various components of the BCMS. An increasingly likely objective is certification under ISO22301.

For some organisations, there are formal and informal statutory and non-statutory compliance requirements in respect of BCM, and these should be referred to in the policy statement.

The sectors where statutory compliance requirements currently exist are financial services, the public sector, the law and listed companies.

It should be understood that while, for the most part, the requirement to maintain a full BCMS is implicit within these compliance arrangements, a BCMS provides arguably the best way to meet and exceed some of these requirements and expectations.

There is a greater variety of non-statutory compliance requirements for many organisations, principally in the supply chain. Just as customers and clients have required that their suppliers meet certain assurance and management systems requirements, such as Quality (ISO9000), Information Security (ISO27001 and ISO27002) Environmental Management (ISO14001) and Human Resources (Investor in People), so BCM is rapidly becoming a mandatory requirement for many. This is clearly a key reason to develop a BCMS and, of course, there is no better way to provide assurance, and meet compliance requirements, than to achieve certification under ISO22301.

An example of a BCM policy which meets the requirements of ISO22301 is to be found in Appendix 1.

Use of the policy

Many organisations are quite accustomed to publishing some, or all, of their policies, both internally and externally, so dealing with the BCM policy should not prove difficult.

Essentially, the policy is both a commitment to doing things, and a mandate to execute the tasks necessary to doing those things; in this case, the development and maintenance of a BCMS. The policy should, therefore, not contain any sensitive or confidential information, so that it can be published widely. If it is useful for the policy to take into account sensitive information, such as financial figures, this can simply be referred to in the policy, it need not be stated in the body of the document.

Scope is a key area where policy can be used to support the organisation’s competitiveness. Some organisations may have a BCMS, or even certification under ISO22301 covering only a part of the organisation, such as the head office functions. Sometimes, the operational part of the organisation, upon which its customers would probably most rely, may not be covered at all. So a supplier which has, or is developing, a BCMS for which the scope is its entire operation, should use that as a competitiveness tool in differentiating itself from other suppliers.