ADVERTISING FROM THE OUTSIDE: INTERVIEW

WITH STEFAN SAGMEISTER.

Stefan Sagmeister is a Grammy award-winning designer. He’s created album covers for The Rolling Stones, Lou Reed and David Byrne. Other clients include HBO and the Guggenheim Museum. Here, he discusses advertising from a design perspective, sabbaticals and what creative responsibility means to him.

ON ADS AND ATTITUDES.

“I ran Leo Burnett’s design studio in Hong Kong for about six months. After that, I switched to advertising within Burnett’s, expecting not to like it, and finding that expectation to be true.

“Hong Kong at that time was an incredibly dense and booming market. It was here that I encountered a behaviour that I’ve noticed at many agencies around the world: there’s too much turning of the wheel and much too little thinking. This applies to both agencies and their clients. Both parties come up with an idea and immediately say: let’s do it. Nobody pauses to ask the proper questions or wonder whether what they’re doing is worth doing. After this initial approval of the idea, there’s an unreasonable amount of time spent on revising, revising and revising again.

“This questionable process leads to dubious work. There’s not much advertising that makes my day. Having said this, there are very rare moments when I see an unbelievable creative peak. When these occur they become part of culture. Examples are the first Sony Bravia TV spot, fig. 10 or certain pieces of Nike work that I just really love as pieces of popular culture.

“These things exist because an advertiser paid for them, of course, and that money can be a force for good. Advertising is what allows The New York Times to exist, for instance. Without advertising, its quality would go down, or it would cease entirely.

Fig. 10: “An unbelievable creative peak.” Sony Bravia’s TV spot, one of the very few ads to get the Sagmeister stamp of approval.

“The fact is that good work requires an unbelievable amount of discipline. If the conditions in a place of work are terrible, then good work is almost impossible to realize. In most ad agencies good conditions don’t exist so good work doesn’t either.

“I remember this from a company like Leo Burnett, but it’s also something I see reflected in friends of mine – people who work in agencies, but all their time is soaked up in meetings, so much so that there’s no time left to come up with good concepts.

“Because these people are working under pressure, they frequently pick ideas from others without crediting them. It’s not that they’re bad people – I do think that the problems are much more systemic than personal. The advertising system does little to bring out the best in people.

“I’ve had friends who took an ad agency job for three years, and in those three years they behaved like assholes. They behaved terribly, not returning phone calls, asking others to work for free, and after six months of free work turning around and saying that the concept has been killed. Then they quit their jobs, left the system, and were perfectly fine again.

“I’m not sure where this rudeness comes from, because it’s been a while since I’ve worked in ad agencies myself. But time constraints are a part of it. I remember from my own career, I once worked on a project for an airline company, but the time I actually spent on the creation of that campaign might have been 3%. Everything else was meetings, revisions, plans being changed, and meetings to prevent the changing of those plans.”

SELLING IS WHAT WE DO.

“Ultimately, advertising is selling. My parents were salespeople, so selling in and of itself is not a problem for me. Ultimately, selling is merely the exchange of goods or ideas, and that’s fundamentally human.

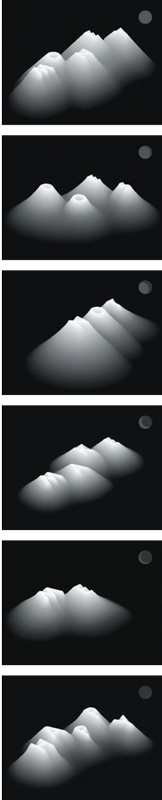

“I’d improve the state of advertising through a few simple adjustments. Firstly, I’d follow São Paulo’s lead. Here, they removed all outdoor advertising. Wherever there was a billboard, now there’s just space, fig. 11 and for me that’s a clear improvement. There’s just no more ugly crap hanging around.

“I spent a lot of time in Indonesia, and that’s the opposite extreme. There you can see how badly they need such regulations. Thanks to small shops with laser printers, everyone’s able to produce very cheap banners. As a result, every possible inch of space is filled with these ugly ads. They are everywhere: in the jungle or next to a remote road.

“I think that one reason the quality of communication is so low in such places is this lack of restrictions. With more restrictions you force people to be clever, to use creativity in order to work around legal impingements.”

THE CYNICAL BUSINESS OF HAPPINESS.

“Advertising treats happiness very cynically. In commercials, it’s almost impossible to represent happiness honestly, because it’s been used over and over again, endlessly. Every brochure features some sort of happy couple, or a smiling baby or adolescent. Through this overexposure, happiness becomes completely meaningless to the consumer. fig. 12 If you see a happy face on a pack shot, it’s unlikely you’ll believe that the product will make you happier.”

One of Stefan Sagmeister’s life lessons, published in his book Things I Have Learned In My Life So Far .

Fig. 11: São Paulo. The anti-advertising capital of the world.

ANXIETY AND CREATIVITY.

“My least favourite part of the creative process is anxiety. But I do believe it to be necessary. If your desire is to create something new, something you haven’t done before, then anxiety will be a component.

“But while you probably can’t do without a measure of anxiety, we try to limit it. Here in my studio we try to keep anxiety in check by setting very generous deadlines.”

CLIENTS TO AVOID.

“If a client approaches us and says: ‘We need something next week’ then we don’t take that client. It’s not because we don’t want to work on something that has to be finished next week. It’s because a client who comes in that late gives the impression that he’s disorganized, and that will lead to future problems. My least favourite client is a disorganized one.”

Fig. 12: What happiness looks like, apparently. Some overly used shots of overly smiley people.

SOCIAL AND CREATIVE RESPONSIBILITY.

“Of the work that we’ve done, there’s one socially responsible campaign that I’m happiest with, and that’s the mobile money campaign. It was about trying to change the United States government’s attitude to poverty by cutting the military budget, and spending more money on education instead. fig. 13

“I like it, but it’s hard to gauge its success because the Obama administration also implemented similar measures. So I can’t really claim a direct effect but it definitely did something. We gained an unbelievable 800,000 members within six months.

“We’ve just been involved with an organization that makes products by asking factions in warzones to collaborate. For instance, asking Israelis and Palestinians to work together, or Pakistanis and Indians, and so on. We did a couple of presentations for them, so it’s early stages.

Fig. 13: Guns don’t kill people, governments do. Sagmeister visualizes the vast sums of money spent by very large countries to guard against a negligible threat.

“In the end, working for NGOs is really, really difficult. Small NGOs have the disadvantage of only being able to do small things. Really large NGOs have the disadvantage of having boards, which means having to get everything approved by that board.

“At one point, I was actually playing with this idea of only accepting socially responsible jobs. But in the end, this doesn’t work financially.

“The furthest I’ve ever been down this path is when we tried to set up our own charity. I wondered whether I should really remain a designer, or switch to the charity sector.

“Ultimately charity work is unbelievably difficult, though. I was pretty mediocre at running a charity, so I stayed with design.

“Overall what is best is working with an NGO in a particular way, to the extent that we really become part of that organization before we even start the project.

In this way, we get to know them from inside.

“If you want to make a socially responsible piece of communication that actually works and has a result, it has to be pure. If I look at the award books and see all the social responsibility ads, I see only a motivation to win prizes. There’s no genuine desire to generate serious results for the client.

“From a creative point of view, I would divide advertising into three groups. The first group comprises the vast majority of what we actually see out there on the streets, or on radio and TV. This is the stuff I’d class as simply terrible. It’s also the main reason I’d rather not watch TV or listen to the radio.

“The second group is the award-winning stuff. It’s very clever and wonderful, but ultimately has been made only to advance one’s career. It doesn’t actually have a function or sell a product. This work is made by grown men and women actually spending serious time and effort to gain a little trophy. The biggest joke is that it isn’t even real. When I judged an ad competition in Asia a few years ago the co-judges told me 80% of all the ads were fake.

“That leaves the third and very small category of excellent work for real clients. And that stuff is unbelievably difficult to do. The people who actually make campaigns that work for clients – selling a product or spreading a message, or raising money for a charity – are fantastic. But they’re only a tiny percentage.”

Fig. 14: Talkative Chair. The text refers to a diary entry Sagmeister wrote while sitting on the balcony in Bali where the fi nished chair would be placed.

BETTER WORKING BY NOT WORKING.

“I take one year off every seven years in order to go on a working sabbatical. During that time I stop working for my regular clients, go off and experiment, try out other things.

“I’ve done two so far in my studio. The first one was in 2000 and led to work that I was really happy with, and still am. A lot of work that we’ve made after the sabbatical was somehow influenced by that period. fig. 14

“Sabbaticals really get more out of you as a designer. I think partly because many people coming out of design school see design as their calling, and that narrowness of focus can limit you. They get used to the stuff that they like, and they get bored of it as well. A working sabbatical helps in getting to know what you like or are good at, next to your daily work.

“Perhaps unexpectedly, the most common reaction I get from clients to taking the sabbatical isn’t resistance. It’s more likely to be: ‘My God, I would love to do that.’

“Sabbaticals are about stepping outside routines. They’re not about working hard because everybody else is working hard. They’re more about what works for you.”

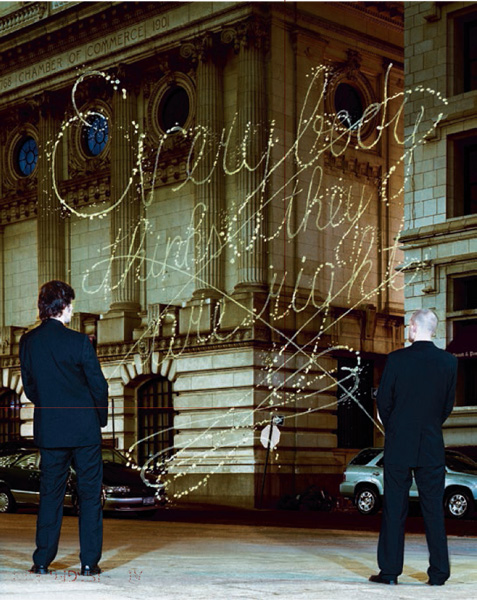

Sagmeister’s billboard for Experimenta, Lisbon. The text is made from newsprint, which fades in sunlight. Over time the message (and the complaining) disappears.

ADVICE FOR WORKING LIFE.

“There’s a book by the philosopher Alain de Botton called The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work. In it he asks: ‘When will we perceive our work to be meaningful?’ He answers this with a single sentence: ‘When it delights people or when it helps people.’

“And I think this line clearly applies to advertising. If you look at the people who have been in advertising for a long time and are still engaged in what they do, you see that they are interested in delighting or helping people, or a mixture of both.”

Sagmeister’s sage words: “Money does not make me happy,” spelled out here in graphic form as part of his book Things I Have Learned In My Life So Far.