1. Companies and domestic economies

1.1. Introduction

Companies are production units, whatever their legal nomenclature or size. They produce and supply finished goods that the market removes or buys, which doesn’t always happen. Producers face a risk: the possibility of obtaining losses. Companies pay certain monetary units to production agents to obtain the product, where this step entails a payment that is called income. This determines the product cost price, which added to adventitious, future or probable income from profits, lets the end product be obtained.

Cost + Profit = Total income6

The business owner organises production and capitalists cede the capital for production, with businesses receiving the profits and financiers receiving interest. But the entrepreneur as a worker earns a salary that is included in total wages.

Companies acquire different supplies or factors with this money. They acquire raw materials, semi-finished products, labour, production services, etc. This is called working capital. Among the supplies that circulate from company to company in obtaining the end product, there are capital, or fixed, assets, which are also included as working capital. This was one of Bernácer’s statements that established a difference from others. Capital goods that are not the object of later transformation and that are immobilised at the end company in order to produce either consumer or capital goods, will be called fixed capital, otherwise they fall under working capital. Companies will also produce services that are used directly by consumers. These services are another production that is added to the production of goods and services to arrive at total national product7.

If these services are produced by a production agent inside the business, they will be calculated as one of the costs in the production of these physical goods.

Companies produce consumer goods and capital goods. Some consumers provide services or work for these companies, receiving wages for doing so. Consumers demand final consumer products and business owners demand capital goods.

1.2. How money works

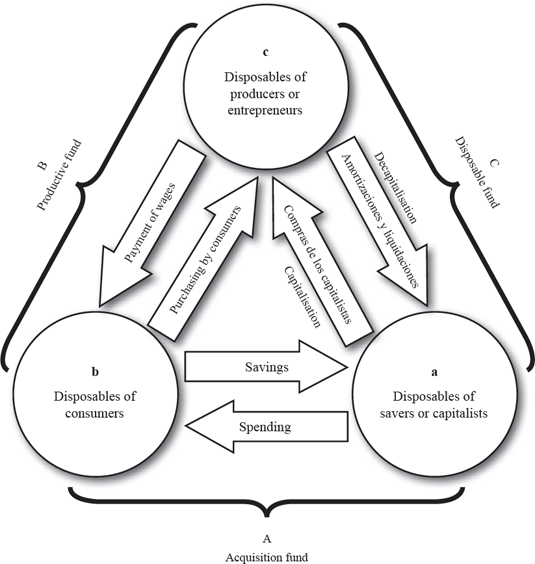

The monetary mechanism represents the continual movement of monetary flow from the producer to the consumer via income and from the consumer to the producer via buying the goods and services. The ordinary market is the place where national product is generated and where it is demanded. Both of these operations involve monetary circulation in the opposite direction of production factors and goods and services, as shown in the graph below.

Companies pay their production agents in income (wages, salaries, interest, land rentals) that returns as income that demands their produced and supplied goods and services. After paying their agents, a sum remains that is profit, which is also income, even when it is aleatory. Reserves are created from the profits that are not distributed, above all sinking funds that finance the acquisition of capital goods and cover depreciation; an operation that is called replacement investment. With the other part of undistributed profits, new capital goods will be acquired when accrued assets allow for it. This acquisition of capital goods will be called net investment.

Replacement investment plus net investment will be called gross investment. But companies put undistributed profits that are materialised in reserves into a temporary destination (even a sinking fund) through the acquisition of real securities, some of which have a speculative aim. Nothing has been mentioned yet about their functionality (although explained in the introduction and explained in detail later). Readers, please stop for a moment and consider this, because it can be a road with no return, which leads to the occasional decapitalisation of companies.

1.3. Say’s law

Say claims that ‘Supply generates its own demand’. For Bernácer, this statement was the overall explanation for the ordinary market described above. National product is produced in this market, as well as incomes. To create the product Q, factors of production are acquired, including the entrepreneur’s work for which he is paid income. Company accounting methods let them calculate the cost, which is nothing more than what is paid through income, to which profits are added to determine the end product that is given a monetary value and supplied.

What is paid plus profits lets the product sale price be calculated. In other words, the product calculated in this way has the value determined by the market. Consequently, income is equal to supply, or what is produced and offered to generate income and demands that are exactly equal. However, Say forgot to give specific profiles to this demand and say that it is the potential demand and not the real or actual demand.

Diagram´ of Disposable Funds

C producers and entrepreneurs.disposable fund

CDisposable fund / Descapitalisation (amortisations & liquidations) /

Capitalisation (capitalists´purchases)

A Savers´and capitalists´disposable funds

Saving/dissaving/Acquisition fund A

b Consumers´disposable funds

B Production fund/Payment of wages/Consumers´purchases

Product * Price = National Income or8

q * p = Y

PNNcf = Y = Potential income * actual Y

The existence of money lets value be measured exactly and enormously facilitates economic transactions. Money also enormously speeds up the functioning of Say’s Law. Thus, demand becomes flexible and is maximised just like production.

Money is like the oil that lubricates the engine of the economy. However, money and its inherent nature will be what make the irregular fulfilment of economic matters possible. This is due to two basic reasons:

1) Money can be hoarded. Monetary oil can be lost along economic circuits.

2) Money demands that which has monetary value, although this does not necessarily mean real wealth in the sense of national product. You will understand these words later.

Bernácer fiercely insists on the identity: production = national income. For him, it is only a mathematical equality, among other things we will look at later, because national product is a physical or invisible magnitude, like the case of services. Conversely, income is basically money or monetary flow.

If money can be hoarded and can demand other things that are not created wealth, then income cannot totally demand what its owners, production agents, have helped to generate. Then Say’s Law is not fulfilled. Income, which is a monetary flow, has led to the creation of national product or wealth. However, if this income is lost due to a hole in circulation channels (hoarding) or moves through a different channel to demand, for example, illusions of wealth or securities (without this security meaning the creation of wealth), then it is clear that this income cannot acquire the product. Potential demand will be greater than actual demand, which has dropped due to similar circumstances, with which period production that gave rise to the potential remains partially unsold. In Neo-Keynesian economics, this unsold part is called or has been called inventory investment (Iu).

This point is fundamental to understanding Bernacerian economics. The explanation of the monetary mechanism is normal, or already explained in economic sciences from that time, although hoarding has not been explained (on which Bernácer placed little importance, except for the gold in the gold standard) and above all the effect produced by demand for fictitious wealth or non-wealth. This will be explained in the section on the financial market. This break in Say’s Law due to hoarding is graphically explained in the following way: Point 1 of the following graph explains hoarding and point 2 the financial market box of fictitious wealth or anti-wealth. As can be seen, Y is greater than Ye, actual income.

The income that returns is less than what was initially output by the production of generated wealth. Ye, or actual income, is lost in 1 through hoarding and in 2 through the financial market.

2. Capital

2.1. Introduction

Capital is defined by two criteria: the first is its duration and the second is its economic nature. Capital, unlike consumer goods that have a short lifespan, is not used up immediately through consumption but is a very slow process. Moreover, capital helps in the production of other assets. Although you will see that this is not always fulfilled.

2.2. A terminological and conceptual issue about capital

Bernácer complained that classical economists used the word capital ambiguously. Given the closed framework of the real and dominant economy with clearly production-based riches, capital for many economists was everything that produced ‘profitability’, defining profitability and productivity as synonymous terms9. For example, for Adam Smith everything earmarked for producing income was capital. In classical economics, this meant productivity. They did not take into account that public debt securities had monetary returns, although this in itself did not necessarily imply an increase in productivity. The terms monetary profitability and real profitability were not the same, at least not obligatorily, and represent the main viewpoint of Keynesian analysis. One thing is capital, which is a factor of production, and another thing is money. Or stated differently, one thing is capital and another thing is the monetary flows that make its acquisition possible. This was the great confusion between classical and neoclassical economists (not all of them); calling two different things by the same name.

In Keynesian economics (words from 1955), monetary income refers to money or, if you like, monetary capital. Capital income is the price of renouncing liquidity. For Bernácer, as you will have the chance to see, monetary income comes from acquisitions made via disposable funds10 of invested savings, of actual secondary financial assets, an activity that is nothing like productivity.

Bernácer’s capital is basically a factor of production. As productivity increases, production is generated that when multiplied by its price generates genuine income for the owner. However, the basic fact is not that income is produced but that assets are produced. These two things are apparently similar and they indeed are the same in the majority of cases. A toll road and a machine produce goods and services that are sold and generate genuine or authentic income. Why do I say genuine or authentic? Because it is income that reflects production. A byroad and a seaport built by the state, even a stereo, produce goods and services for a collectivity, although they are not sold and thus do not generate monetary income, although it is real (without bias to the fact that monetary profitability could take place).

2.3. Classes of capital

Capital, as that part of the flow produced that is used to increase production, is divided into fixed capital and working capital.

2.3.1. Fixed capital

Fixed capitals are production instruments whose production life lasts for a longer period –much longer– than the average period of maturation of the company or production period.

It is understood that out of all the production of the industry, a series of end goods have been produced that will not be moved to another company for their later transformation and incorporation of added value. Out of these end goods, those that are not end consumer goods but factors of production are called fixed capital.

This is very important, given that if they are not end goods, but intermediate ones, these production instruments that were initially called fixed capital turn into working capital. The nature of fixed assumed in capital or a tangible fixed asset in accounting terms (not all tangible fixed assets are machines or capital), is not established due to being productive and temporary, at least not totally, as it must also be an end good.

If a company acquires a machine that will be improved or its production capacity increased or if this company produces a machine for an end or intermediate vendor, this machine, even though suitable for production, stops being fixed capital and is then called working capital.

Fixed capital equipment wears down with usage over a series of years and this wear is called depreciation. Out of undistributed company profits, or savings, S, a quantity is created to proportionally compensate for this depreciation. This is the technical amortisation that entails costs to the company. This temporary and daily cost prevents companies from decapitalising all at once. In fact, decapitalisation cannot happen instantaneously but over time. The situation is not the same with working capital.

A production flow of products is generated in the system, where these products are fixed factors of end production. This process will be called capitalisation (and not investment). This flow is divided into two portions: one is destined for the compensation of deterioration of capital goods and the other at genuinely increasing capital goods. Bernácer expresses this in the following way: liquid capitalisation is the difference between total capitalisation and amortisation done at the same time. In the economic system, someone may also sell capital equipment and this is when it is fully decapitalised. The equipment is, but not the system, which continues to have the same amount of capital goods, since the capitalisation of the buying party is balanced against the selling party that has decapitalised.

However, if the creation of capital goods was possible due to savings, successive buying and selling of the same capital equipment innumerable times will occupy high quantities of savings to execute the same capitalisation as before. This operation of repeated sales and purchases, although possible, lacks quantitative importance in Bernácer’s thought with respect to capital goods. It doesn’t usually happen frequently. It will though be important for actual secondary financial assets and will give rise to the financial market.

2.3.2. Working Capital11

Factors of production that are wholly consumed during production tend to be called working capital. The company monetarily and truly is decapitalised all at once through production and recovers monetarily and truly at the end of the production cycle via the finished and sold product. Merchandise, in the hands of producers and merchants, comprises part of their working capital, since they have to pay for them with their own resources. It is working capital because it is recycled both periodically and permanently and because when the merchandise is sold to some consumers and to some other producers, they employ these resources from sales in reproducing these same articles or others.

All of these ingredients that are involved in working capital, are they semi-finished, finished products for consumption, raw materials, work, energy, etc. only? The response is no. Producers of capital goods –capital articles in the terminology of our economist– also call it working capital while it remains in their possession. An example is that a flour mill owner calls the flour he produces working capital and the tanner calls his hides working capital.

Types of working capital12

Here, we are entering a field that is replete with polemic and debate. And it would be the same for a student that had just started to study the rudiments of economics. I do not understand how Bernácer, who explains everything precisely, methodically and clearly, introduced such a dangerous classification, although he does do so clearly.

In the consecutive production rhythm, or the inter-industry or inter-business production chain, products continue to receive successive added values until the end product is obtained. The value of the end product is only the sum of these net added values (‘net’ is added for clarity, although it is redundant). Everyone knows this and Bernácer knew this and explained it as follows. Here is the problem in understanding Bernácer. What happens if the value of wheat is added to the value of milling this wheat? Well, then we have the total value of the milled wheat and so on until obtaining the value of the bread. And what happens if the value of the bread is added to the total value of the wheat, plus the total value of the milled wheat, plus the total value of the manufactured flour, plus the total value of the baked flour, etc.?

Then, the basic rules of cost accounting and the most elementary macroeconomics would be neglected, which prohibit factoring the same thing twice. So Bernácer is undertaking a unique activity, but don’t believe that this will be the result of estimating the national product. His definition is the same as the one used herein, or the value of the sum of the added values. What he did is add or enter into the books twice or even more times –a mistake– all production to then subtract the value of the net national product. The difference obtained is what he called second-class working capital.

This will be explained by two examples, one graphical and the other numerical.

Capitalised sums, or if you like invested sums, generate two classes of working capital: first-class working capital and second-class working capital. The first stops directly at consumers, although part of this group will be manufacturers; the part that is fixed capital. This is the national product. Second-class stops at producers and manufacturers. The graph will let you visualise this with greater clarity.

Each production phase adds value to the previous production and the sum of all the net added values is equal to the total added value, which for Bernácer is first-class working capital. This working capital is the national product.

The value of the national product is measured by the length ag, which is the sum of all the previously-added bars ab, bc, cd… A longer length means a greater national product and vice-versa. The value or manufacturing of this first-class capital has led to a series of monetary payments that represent an increase in total income. This working capital is not liquidated until it is sold and is then owned by the total group of consumers and financiers.

In addition to first-class capital, second-class working capital is needed, which will be the sum of the shaded area of the bars. Once again, this sum is not the national product, but second-class working capital. It can be measured as follows:

If total working capital is:

In phase one: ac

In phase two: ad

In phase three: ae

In phase four: af

In phase five: ag

Total working capital is the sum: ac + ad + ae + af + ag = X

This is a fact or should be clear, given that each production phase counts the materials that arrive from the previous stage, like raw materials, semi-finished products, etc., as working capital. The total supplies in each phase are thus the products from the previous production stage.

If first-class working capital is subtracted from the total working capital, the result is the second-class working capital:

X – ag: 2nd-class working Capital

or in other words:

X = total working capital =

= First-class working capital plus second-class working capital

Several comments can by made here. The first is that working capital is not comprised only of money or only of raw materials and semi-finished products, but by both of them. From the total production of consumer goods. It is expenditure on consumer goods. With savings, capital goods are acquired. What would happen if you acquired working capital instead of fixed capital with savings? If fixed capital is acquired, the capital in our possession is immobilised and savings go to the producer. But if working capital is acquired, new payments and new productions are created. This new production will be combined with the previous one, which are the final capital goods awaiting demand, compared to the single purchasing capacity generated. This wait will be useful. Let me state this more clearly. The financing of working capital with savings entails two productions compared to only one demand that will be monetarily less. The new product created and the old capital goods will be production, and demand will be a reflection of financial working capital. This will be seen towards the end of the book when economic crises are analysed.

Another in-depth example will be given of the ongoing process of generating added values and first and second-class working capital.

Before continuing, remember that while an instrumental element or production factor has not been totally immobilised in the hands of the end producer, it is not fixed but working capital, along with the raw materials, semi-finished products, energy, money, etc. Working capital requires financing and if this working capital is greater due to successive additions of more working capital, the more need there will be for working capital. Obtaining the product requires ongoing incorporations of working capital in successive production stages until reaching the end product. This product will be comprised of end consumer goods and capital goods (if they are not final, they are still working capital).

Stratification increases the need for working capital, since not only does it require the indispensable sum to keep the product obtained in circulation, making it possible to pay the income of this asset manifested in money, but it also requires payments between companies that take place in the added transformation.

Let us continue with his example. The first was detailed in The Functional Doctrine of Money in 1945 and the second in 1955 in A Free Market Economy without Crisis or Unemployment.

An aside is relevant here. Bernácer knew accounting techniques since he was a business teacher; he had normal common sense and in 1962 he was 62 years old, an age at which he was obviously completely familiar with the national books and articles published on accounting.

Let’s continue with the example: A clothing production company adds successive values until obtaining the final product employed. The value of the raw fibres, the thread, the fabric, the clothing, etc.

| Incorporated costs | Accrued values | |

| Value of the fibres applied ............... | 20,000 | |

| Value of the thread ......................... | 25,000 | 45,000 |

| Value of the fabric .......................... | 15,000 | 60,000 |

| Value of the clothing ...................... | 30,000 | 90,000 |

| Profit margin .................................. | 10,000 | 100,000 |

| Final production value ................... | 100,000 |

Each phase adds its value to the production, so that as the production processes occur, the greater the amount of working capital that will have to be paid. The individual acquiring the fibres pays 20,000 for them and adds a value, that of the thread, of 25,000, which at this time is an added value or production of 45,000. The next individual will add a value, exclusively 15,000, but he will have acquired a production of 45,000 from the previous stage (20,000 + 25,000). In this period, production is already worth 60,000 and will be what the next producer will pay (for his supplies) and individually, he adds a production value of 30,000, which is for making the clothes. The cost of the supplies he acquired was 60,000, to which his cost of 30,000 is added, for a total production value of 90,000. The merchant then acquires the final product (working capital for him) and adds a margin of 10,000. What did the product cost the merchant? He bought it for 90,000 and sold it at 100,000. Let’s simplify it even more. The payments made were:

100,000 consumers

90,000 retailers

60,000 clothing producers

45,000 weavers

20,000 spinners

315,000 total payments

Actual total payments are exactly 315,000, but this is contrary to Bernácer’s opinion, who does not believe that these monetary units are required for the operation. How would Bernácer formulate this operation? He would calculate the second-class working capital.

Total working capital (315,000) minus first-class working capital (100,000) equals second-class working capital (215,000).

315,000 –100,000 = 215,000

The figure of 215,000 is the new money that Bernácer asserts is required. For me no, since the same monetary mass can execute several transactions in the chain of successive transactions. This is easier to explain by continuing with the example. While true that retailers have to pay 90,000, the dressmakers 60,000 and so on, it is also true that those who pay, for example 45,000, receive 60,000 and those who pay these 60,000 sell for 90,000 to others who pay it and in turn sell them at 100,000. In short, I do not believe more money is needed than that deriving from production and national income.

2.4. Financing capital 13

Capital must be created, which requires money and, after creation, be bought, which also requires money. Fixed capital and working capital must be financed with producers’ money. Financing funds come either from bank loans, which are others’ savings, or from their own savings, which are undistributed profits.

Undistributed profits are periodically used to create a sinking fund. This is one operation. The other consists of acquiring capital goods to cover this depreciation or loss in value of capital goods, an operation that is called replacement investment. This is another operation. Amortisation is an accounting operation that is not always related to a loss in value of the fixed capital. The aim of the amounts now undercapitalised by depreciation is to recapitalise them via a technical amortisation. The company wants to acquire new capital goods, which is the net investment. Investment is always a financial operation entailing an expense.

One thing is new fixed and replacement capital and another thing is the investment. Investment entails the act of buying this capital good or receiving financial assistance (expense via a loan) to create it.

The final capital good becomes an almost-permanent good for the company. There is a reason why accountants call them ‘immobilised’. Company accountants and economists know that this cost is also a financial asset. The yields generated by fixed assets are supplied over the course of their long useful life and matched against the financial amortisation or repayment of the loans that permitted their acquisition. Long-term loans and/or profits let these production fixed assets be acquired.

Working capital has a more fleeting existence. And the shorter the better. Its nature makes it disappear quickly. Companies go through a continuous process of continually capitalising and decapitalising working capital. The decapitalised working capital feeds the new working capital. If decapitalised working capital does not return as new working capital, it remains in the hands of the producer as disposable funds, money that in principle is neither consumed nor capitalised.

Frequently, when the economic system truly grows, it requires more liquid resources to finance new working capital. This means that the former working capital is not enough to generate enough liquidity to make an increase possible. Then a short-term bank loan is turned to. As successively added working capitals generate the national product or first-class working capital, loans are similarly necessary so that the economy can grow and not stagnate.

The nature of capital requires a specific loan type. Fixed capital is wholly recovered over a long period of time. It would thus require a long-term loan. However, for Bernácer, fixed capital required savings or undistributed profits for self-financing. A coordinated and extended sequence between the two makes equilibrium between the operations possible. Conversely, working capital decapitalises quickly and lets resources for financing be obtained quickly. It should and is basically dependent on bank loans14.

The inability of the system to self-finance the period’s production with monetary resources created in the period must be stressed. The system generates production comprised of fixed capital and consumer goods, deriving income through this process, part of which will then be allocated to consumer spending and part to capital goods expenditures. If this operation is done, it is clear that more resources are needed to finance the working capital. This means that system savings does not provide, or is not enough, to finance both the fixed capital and the working capital.

Proof of this statement is the following: Imagine that period savings were used to finance working capital instead of fixed capital. Then a new product is added to production, which is a new supply. Simultaneously, and as a consequence of this investment, new income has been supplied at the exact value of the working capital. Two productions are generated from this new income or potential demand capacity, one that is the new production source (equal to the new income) plus the fixed capital that is no longer demanded because the working capital demanded it. This is Bernácer’s explanation of economic crises. Savings in the system resist being invested in fixed capital, perhaps due to the uncertainty of their prospects. Then monetary resources or savings is placed into working capital, whose recovery is faster. What they believe is suitable, the system believes is harmful. Fixed capitals have stopped being demanded and thus represent a permanent supply that is added to the new production arising due to investment in working capital. Two supplies are thus on the market, the one from the previous period, which is the capital good, and from the current period, which is the new, although there is only one buying capacity, which, no matter how you look at it, is less than this supply. This is when a deadlock is produced in production.

2.5. Capitalisation

Do not confuse the production of real capital, either fixed or working, with its financing. They are different acts done by different people that the market tends to always lump together. Since it seems like companies produce real capital and they do indeed, many also believe that companies capitalise companies. This is not true, what companies really do is produce fixed or working capital goods, and the function is to produce. So who capitalises or carries out financing? Fund holders (holders who may or may not be the owners) finance the creation of fixed and working capital with these funds. These funds are the liquid savings supplied by savers through the financial system and new liquid money created by banks.

With these transferred funds, producers acquire raw materials, pay wages, electricity, produce fixed capital, etc. These functions receive the name of production.

There is another difference here, which is the difference between capitalisation and investment. If capitalisation is financing with funds –let’s call them savings– from fixed and working capital, an operation necessary to the system, and investment is the act of buying or demanding fixed and working capital goods, made possible with savings, then one could think that there is no difference between the two operations15. For a start, the difference between savings and the operation performed with these savings must be clear. To Bernácer, capitalisation has a real meaning and investment has a monetary meaning. Capitalisation means the financing of a specific number of capital goods, for example 5 power saws. Investment has a monetary meaning, as it implies a transfer of funds that can be greater without the actual capitalisation necessarily increasing as well, owing to price increases. One can invest a much larger amount in a future period than an earlier one and obtain the exact same merchandise, for example the five power saws or even less. The opposite cannot be true, that our power saws are capitalised more now than before and invested as well.

3. The market

3.1. Introduction

The market is the meeting point between supply and demand. And where the goods from the system’s production are traded. In order for this trade to take place, the goods must be produced and then demanded in a price-quantity ratio determined by demand. Theoretically and when balanced, this is possible due to the fulfilment of Say’s Law.

Since production has originated the demand through the payment of income equal to contributions to the production process, the operation of the market remains secure. This is when money appears, which in principle fulfils the mission of facilitating interchange and distributing wealth among producers.

On the market, not only is current production merchandise offered from the same period, but also others, such as consumer and capital goods that were produced earlier. The money generated for and by the ordinary market, which is where national product is produced, is exchanged for anything with a value, although this is not real wealth or even real production. There are goods with only a monetary value but lacking real value. These are secondary financial assets and secondary real wealth. Both help in the formation of national product, although they continue to stick around after fulfilling this purpose and possibly with a greater monetary value. In any case and whatever their value, they do occupy a monetary mass for transactional purposes that, coming from current production, do not return to it due to the aforementioned reasons. These financial assets, such as stock market shares, speculation in city property, gold itself, etc. are demanded because free income is obtained (not production income) simply by having them in your possession through dividends, rents, etc.16 They are also demanded because they accrue speculative capital gains. They are not consumer or capital goods since they do not represent new production of consumer or ca pital goods either during the current period or in successive ones. Neither do they represent new consumption as nothing is consumed nor is capital applied to produce something, as nothing is produced. As said, they do lead to monetary earnings, although not real ones.

Thus, what is good for one person is bad for the system, because monetary profitability steals income from real profitability that is the child of current production. This is a mainstay of Bernácer’s thought that is highly original. Thus, there will be two markets, the first trading in production merchandise and the second trading in financial products. Wealth is produced, income is generated and goods and services are traded in the first and in the second, speculative goods, shares or past wealth are traded.

3.2. Production and supply on the market

On the ordinary market, supply is established by the production articles sold, which are divided between consumer goods and capital goods. The misnamed inventory investment is also added here that is made up of unsold consumer and capital goods. In my opinion, there is something more that Bernácer did not emphasise clearly enough, which are the goods in the production process, or working capital. Let’s stop here for a moment.

Semi-finished products, or in other words still in process; and raw materials, or stock in the industry, are working capital. Concretely, the non-liquid part of working capital. One cannot call them stock since they have been demanded and applied to the system and will be new production and supply in another period. The ordinary market can be depicted in the following graph.

This supply of goods will accrue and also include the supply of financial assets (our real secondary financial assets that I will simply call our financial assets). These assets do not enter the ordinary market as supplies, although they do comprise part of the total market.

3.3. The formation of demand

National income flows from production. Basically, it is a monetary flow that is supported by, besides said income, the creation of money by the system. As you know, this income is allocated partly to demanding capital goods, stages that require the prior creation of savings, and partly to direct spending on consumer goods. There is another part that is not for expenditures on consumer goods or capital goods and that remains liquid temporarily. They are disposable funds: D.

These disposable funds, which exceed basic needs for consumption and production, normally form to acquire new financial assets. As the formation of demand explained here pertains to the ordinary market, they are outside the graph, which in some way shows that they do not exist. These disposable funds may decrease since they may be allocated for buying consumer and/or capital goods in certain cases. But they can also increase due to abandonment of current production goods or because the financial market is no longer of interest, permitting the monetary resources there to return to the ordinary market.

The following graph was created in 1955. It shows the allocation of income flows by demand, which are exponents of what was published in his famous article about the theory of disposable funds from 1922. As Bernácer was sensitive to any accusation of plagiarism or anything that questioned his originality, he commented on his 1922 article in his book A Free Market Economy without Crisis or Unemployment (1955).

He says that he and Keynes basically differ on the following issue: for Keynes, savings S only has one destination, which is capitalisation. However, the Spaniard claims that while part of savings S is capitalised, or in other words, Sk is invested, there is another part that is not: D = S – Sk, where this remaining part is the disposable income fund, which will nourish the financial market. Keynes would believe that the right-hand bottom square of the following graph was missing from the previous graph (disposable fund D).

Diagram of the formation of total demand

A convincing and blunt criticism will be made now. Investing savings must be focused not on the fact of producing or creating these capital goods, but on the sale of the capital goods or, if you like, on the purchase of the capital goods by financial investors. Producers produce and investors invest; two operations that are different, albeit complementary. One of Bernácer’s most important criticisms of traditional thought may consist of the belief that a capital good is an instrument that assists production and puts it into operation. This contradicts common sense and especially economic common sense to add up two heterogeneous and opposite things: one, capital goods, and the other, inventory or stock investments. The first assists production and the other hinders it, given that it does not motivate entrepreneurs to produce more. Moreover, investment exists precisely because it entails the manufacturing and sale of something, capital goods, while inventory investment is generated due to lack of demand. ‘Why on earth would they be added together?’ Bernácer asked himself. Due to a simple methodological trick, consisting of giving them a monetary version by multiplying each item by its price to make them homogeneous.

There is more. It is said that there is physical capitalisation when a permanent good is created. All right, but until someone buys it, this lacks functional economic meaning given that it means that this good has not been demanded. But this is still not enough. They say that there is capitalisation, a basic operation, when this same capital good is put into operation by users after being produced and then bought (demanded). Depreciation, amortisation, manufacturing, investment, replacement investment, putting capital into operation, etc. How many nearly analogous concepts and how many different concepts! The crisis can be explained precisely because they are different.

Keynes’ great critic comes to his defence and against his mistaken students (quoting Samuelson among them). It is not that Keynes was wrong in considering that the destination of savings (savings born from income) is equal to the investment in fixed capital and inventories. With acuity and wit, he explained Keynes’ thought by explaining that what he really meant to say, given that income springs from prior real and equivalent production, is that what is not consumed has its balancing entry in existing merchandise17.

3.4. The role of money

The total market demands the concurrence of supply and demand. In macroeconomic terms, this entails coordinating total production with total income, the child of previous production. Both aspects have been dealt with separately and, moreover, insufficiently. I say insufficiently because anti-wealth or dead wealth would have to have been added to the market setting or, in other words, our financial assets. I will leave these operations for later. These operations will be those of integrating the national product and income into a single market, which are first the ordinary market and then the introduction of the financial market into the ordinary market.

The financial market, the ordinary market and both markets together trade using money. Why? Because one of the advantages of money is that it monetarily represents any good in general, unlike for example a bus ticket.

Then any buying and selling operation requires the intermediate participation of money. I include the conclusion of one of Bernácer’s oldest and most important writings. He stated that ‘whoever offers merchandise is in reality demanding money and whoever is demanding merchandise is offering money’. For Bernácer, this concept is also long-standing in economic science and economists have uselessly complicated it. Specifically, classical economists were aware of disposable funds. Walras also knew of them and called the operation encaisse désirée, or desired cash balance, and Keynes called it liquidity preference. Understanding it is also simple and the explanation of the economic crisis will also be simple.

There is something else. As our financial assets are also the object of buying and selling, we can conclude that whoever supplies these financial assets (don’t forget that a specific type of real assets are also involved) is really demanding money and the party demanding these financial assets is really supplying money. I will jump ahead briefly to a topic I will analyse later, which is interest. The price originates from the supply and demand for produced goods and services and the market price value originates from the supply and demand for financial assets. This market price value, related to the income it produces, generates an average price for this income, and this price is interest (non-production income).

If you believe, like the classical economists and, probably, even earlier economists did, that money is only useful for trading generated production, you will be making a serious mistake. This is something that Turgot’s genius intuited. But he did not analyse the money market and by not analysing it, he avoided the main problem, which is like bullfighting without a bull and without an arena. Keynes’ success was to mainly study the problem of money, although in Bernácer’s judgement, he did not focus correctly on the right problem.

What is the problem or the issue? It is to analyse the double cycle of the fluid income of money in two markets: the ordinary one, from which production and income arise, and the other, which is the financial market. Both real and artificial wealth is traded with money, which originally comes out of the mechanisms of the ordinary market. As mentioned, this income is a monetary flow, part for consumer spending and part that is saved and later spent on capital goods or invested, but a third part is comprised of disposable funds, D. The latter are used to trade on the financial market.

Note that disposable funds are formed because income has already been drawn away as a consequence of having financed consumption and capitalisation, both operations vital to consumers and business owners, respectively. But since the institutions taking these savings are usually others, or maybe the same, along with investors, this group as a whole does not provide for the satisfaction of basic needs, but rather to monetary or speculative profitability. In short, consumers and entrepreneurs save and these savings are given to credit or financial entities. Then, the parties asking for this money may be investors or speculators or other parties. In the end, credit entities are interested in these loans being repaid with interest. As mentioned, producers do not finance, they produce, leaving the investment function to capitalists or other parties.

And it will be this continuous movement of monetary flow between the ordinary and financial markets that will give rise to alterations between the prices and interest rates in both markets, causing situations of boom and of crisis. This mechanism can be explained as follows:

Complete diagram of the circulation of the total market

(including the ordinary market and the financial market)

3.5. A functional classification of money

The aptitude of money is exchange. This has been and will be basically its function and task. If it is saved, it is to save it for better exchange opportunities. Whoever has the money and wherever it comes from, this will be its function.

The price of merchandise is determined by the amount of money exchanged for it. This merchandise-money ratio is called price. The market price of securities or financial assets is determined by the amount of money given in exchange for them. It does not matter if one means the generation of new income and national product, because everything that has a value can be represented monetarily (although the opposite argument is not always true).

Where M is the monetary mass and Q the merchandise volume, the price P will be determined by the formula:

M / Q = P

Two comments are relevant here: The first is that the speed of the circulation of money is not taken into account. The second is more interesting here and it is that there are more things that are the object of exchange and they are our financial assets V.

Thus, the monetary mass will be divided to make two transactions in the two markets possible. Bernácer did not explain the new equation that will connect two different price levels, but one can draw a conclusion from his explanations on the functional theory of money.

Bernácer wondered ‘how can the supply of and demand for money be computed?’ This is the same as asking, ‘How is the price of money determined?’ The answer is: Money is supplied to demand goods or to buy and money is demanded in exchange for supplying merchandise. It is the symmetric and simultaneous inverse operation to the supply and demand of goods. This is how Bernácer explains it.

However, in the brief explanation he gave on page 48 of a Free Market Economy…, he forgot that the same supply and demand operation for money is done to exercise the supply and demand for our financial assets. As Bernácer repeatedly revealed this operation throughout his work, it is not an error but a methodological scaling that helped support his explanation.

An aside here is to recall that the system continuously requires new money to finance working capital. This will be transformed into first-class working capital, or national product. Savings in the system is a flow of income that has come from this national product and that will demand –at least potentially– fixed capital. This is in theory. What is true is that the money created by the financial and banking system finances consumers, producers and savers. Everyone does something different with their money and when an operation is done, it places this money in another economic stage in which, in turn, another agent will use it for another function. There is an internal mechanism that is precise and orderly in the economic body, which does not mean healthy or efficient, and makes money circulate methodically (not rationally). The different functions of money or the many different functions that make money possible depending on what phase it is in are what breathe life into this economic body. This theory is better than the quantitative one that encodes everything in numbers and also better than the income-based theory although it closely resembles it, contrary to Bernácer’s opinion.

The diagram below explains the functional mechanism of money with the following new feature with respect to Bernácer’s original design. Money from the financial market comes exclusively from savers’ money, the reason why the line for this money is left open in the diagram. In any case, Bernácer himself explained this, although it did not appear in his diagram.

Although it may appear trivial and obvious to economists, it does explain the basic monetary functions from a different –not opposing– viewpoint than traditional macroeconomics. Bernácer was 72 years old when he published this work, which magnificently and completely structured the basic functions of money. In the chart, everything will depend on who has the money and what they do with it.

In short, the diagram is divided into two parts: the top, which shows the total group of sellers or supply; the bottom the total group of buyers or demand. And above both of them, the creation of money.

The arrows that go from right to left, or counter-clockwise, show destinations or monetary operations and answer the question: What is done with the money? The arrows that go from left to right, or clockwise, show the economic operations that are complementary to the previous ones.

In (1) entrepreneurs create the national product and to do so they make payments that are income in (2). The consumers in (3) receive this money, saving part of it and moving onto (4). These saved resources change hands to the savers in (5), with part given to producers to repay capital and make capitalizations, new operations that take place in (5). Bernácer explains here (although not appearing in his original diagram) how part of the non-capitalized savings escapes towards the financial market. It is extremely important to emphasize a fact. The financial market as a mere bridge between savings and investment, in accordance with Keynes and any macroeconomics textbook, will be found only in (5). This innocuous –as well as efficient– market is part of the money market and part of the ordinary market. On the contrary, our financial market, which is also another market, is outside, since its functions are opposed to the circuit in which the ordinary market is developed.

Now let’s go in the opposite direction around this circle. With the wages and payments received in (1) and (2), purchases are made from producers. They, in (1), receive them in the form of income. They perform functions with it, as stated, of amortization and capitalization in (6), giving resources to savers to do so. They also receive money from these savers to execute these functions. Savers can also dissave, an operation executed in (4) and spent, after it forms part of consumers’ money (3) in (2).

It can be added that the creation of money flows either to the group of savers or to the group of consumers. Bernácer clearly did not express a common operation, which consists of the fact that the creation of money can also go directly to the financial market18.

4. Potential and actual demand

4.1. Introduction

Say’s Law states that the cost of producing a good or service is equal to the cost of the product itself. This is undeniable. Thus, Bernácer observes that two things come from the production process, wages and salaries on the one hand and the product on the other. The manufacturing cost of the product is the monetary price of all payment. National product is equal to the period income.

In Bernácer’s opinion, what Say forgot was that one thing is for demand to be numerically or potentially equal to supply, and another thing entirely is for all of this potential to really be demanded, or that demand takes all period production. Thus, he distinguishes two types of demands: one is potential and the other is actual.

4.2. Potential demand

Potential demand is the total demand existing on a market in a specific period. In pure and balanced terms, it would be equal to national income. I say balanced because unspent income from previous periods and the creation of money have been left out here. This theoretical and potential demand won’t be taken into account, just that which exists on the market during any period of time.

Suppose that there are 10 million euros distributed among companies that hold 4 and individuals who have 6 million, with the latter group made up of consumers and holders of liquid savings. In the subsequent period, the income received by individuals for their participation in production will be added, as well as the creation of new money that will end up in the hands of buyers.

The only payment method that would not be at the expense of production will be at the cost of public funds, which are collected via public debt and new money created for this purpose.

If total period income is 300 million and there is 30 million in new money created, potential demand will be the sum of these two items plus that from the period.

| Buyers’ resources ................................................... | 600 |

| Total period income ................................................. | + 300 |

| Increase in the amount of money .............................. | + 30 |

| Potential demand ..................................................... | 930 |

The fact that there is a potential demand of 930 is one thing, but whether it is all spent is another issue entirely. The pace and frequency of collections and payments are never constant. Companies and consumers keep reserves for many different reasons. Often savings are made to accumulate a certain amount for a future purchase, etc. Savings also has a direct relationship with the length of time between collections and payments. Suppose that the accrued remainder at the end of the period is 610 million.

4.3. Actual demand

When income is spent, either on consumer goods or capital goods, this means that money has moved from some economic agents and been given to others in exchange for a series of goods. This operation is called actual demand and is calculated by subtracting what is left in the hands of economic agents from total potential demand, or the sum of total income and new money created. Thus, continuing with the previous example:

| Potential demand ..................................................... | 930 |

| Remaining at the end of the period ............................ | – 610 |

| Actual demand ....................................................... | 320 |

Not all money that moves from individuals to companies will be actual demand, since part of this money will be transfers of funds made by savers or bankers. So this transfer of funds must also be subtracted from the total actual demand, using the figure of 55 to continue with the example. Now actual demand will be:

| Potential demand ..................................................... | 930 |

| Surplus after purchases ............................................ | – 610 |

| Advance payments to companies .............................. | – 55 |

| Actual demand ....................................................... | 265 |

Fund transfers can also take place in the opposite direction, such as for example the repayment of loans made by companies. The real and normal monetary growth of the economy means that companies receive more than they return. This is only with respect to monetary funds. The figures subtracted above are net figures.

Companies can use the money received in several ways:

1) Save it in cash as reserves

2) Use it to increase working capital

3) Allocate it to increase fixed capital

The effects on the economy will be as follows:

In the first case, there will be no real effect. This is because the money goes from savers to companies and then the companies become the savers.

In the case of spending it on working capital, this translates into production and the creation of income, surplus money, products being produced and not yet sold, etc., all of which has already been accounted for when estimating total income. No rectification needs to be done.

In the last case, if the money received is allocated to increasing fixed capital, then actual demand increases, since there is an increase in actual demand still not calculated. This is explained in the note below. Now, let’s increase the total actual demand by the fixed asset purchases made by companies during this period. What does this mean? That from the transfers of funds, only those allocated to increasing working or liquid capital must be added. If immobilised assets were 40, then actual demand will be:

| Potential demand ..................................................... | 930 |

| Surplus after purchases ............................................ | – 610 |

| Transfers to companies ............................................ | – 55 |

| 265 | |

| Company immobilised assets ..................................... | + 40 |

| Total actual demand ............................................... | 305 |

Note: I said that what is acquired as working capital has already been entered into the books because these amounts have been produced and bought with period production.

The capitalist capitalises or invests and the producer produces capital goods (as well as consuming, naturally). When somebody builds a house, he employs factors of production and, upon finishing it, he has increased both production and income. What he acquired with savings has been capitalised. This payment made with savings may have been during construction, thus financing it, or after the house was finished. In either case, it is capitalisation or investment and therefore a purchase.

For the construction company, while the house is not sold, it is working capital, which is transformed into fixed capital when acquired by a buyer, who ‘immobilises’ it. What does it mean that it is an immobilised asset? That the buyer removes it for himself, thus taking it off the market.

4.4. Potential supply and actual supply

Supply is the total goods and services generated during the period that is in balance. I say in balance here because in this state, there are no products accumulated from past periods. Potential supply is equivalent to potential demand. Actual supply is what is really supplied.

Supply is made up of a diverse group of things, which can be monetarily represented by multiplying each item by its respective price. And since prices are established by the market, the price can not yet be determined while the object is unsold on the market. How will potential supply be established in monetary terms? By calculating it by its cost, where this cost is always somebody’s income. The cost price does not include the business’ profit (sales price), due to which it can be said that the supply cost is the potential supply, which is equal to potential demand.

Bernácer repeats this over and over again from different angles each time. In this way, he reveals previously unnoticed aspects.

Potentially supplied products will be the sum of current production plus currently unsold products (nothing should make you think that there is balance).

From the potential and theoretical fulfilment of Say’s Law (not actual), the following conclusions can be reached:

1) The value of what is produced is equal to what it cost to produce it and this figure is income that has been paid; then the period income is equal to the period production value.

2) Potential supply also includes the value of stock, which are also represented monetarily in period income. Stocks naturally include raw materials and semi-finished products and finished products, meaning factors or supplies from the subsequent production sequence. In other words: working capital.

| Value of stock ..................................................... | 500 |

| Period production ................................................. | + 300 |

| Potential supply .................................................. | 800 |

3) Actual supply will be equal to the potential supply minus what remains to sell. Thus:

| Potential supply .................................................... | 800 |

| Final value of stock ............................................... | – 505 |

| Actual supply ...................................................... | 295 |

4.5. Market equilibrium and disequilibrium

Potential demand and potential supply, in the absence of new money and fund transfers to industry (net), will be equal, which does not mean this is true actually. With everything, macroeconomic figures using conventional accounting rules tally up. And the fact that they tally or are equal in assets and liabilities, does not mean that balance takes place.

In effect, all increases of money in the hands of consumers and capitalists –increases and non-increases in spending– means that for the moment, it has not been spent and must inevitably be represented by an amount of merchandise that is unsold. This means that there will have to be a constant equivalence between actual supply and actual demand, and frustrated and unsold supplies and demands not made. Bernácer called this unsold stock ‘E’ and available funds ‘A’. This is an aspect that Bernácer would deal with in depth from a strictly-monetary viewpoint, representing the arsenal from which he would criticise the essential macroeconomic equation.

This line of reasoning clearly demands price stability, at least in the period. Let’s continue with the example: Where 300 million is the value of production, 500 the stock in company merchandise at the beginning and 530 at the end. It is logical to understand that the increase in merchandise by 30 entails that buyers have not spent and have accumulated (disposable funds) for a value of 30 as well. I must repeat that there is no creation of money, transmission of funds or price variations.

So what does the 30 represent? A temporary market failure that demands an explanation about why consumers’ disposable funds have increased. It may be due to trivial or circumstantial reasons and that sooner or later, these resources will be spent. At this time, and given the advanced knowledge employed up to now, a theory cannot be hazarded. The theory of interest and the financial market must be studied first to understand the perpetual and growing formation of disposable funds. Thus, the term that macroeconomics employs to designate unsold merchandise will be criticised roundly here. It is called nothing less than: investment in stocks or inventory investment!

The supply from the example will be:

| Disposable funds of buyers | Articles of sellers | |

| At the start of the period | 600 | 500 |

| Period production | + 300 | + 300 |

| Potential demand and supply | = 900 | = 800 |

| At the end of the period | – 630 | – 530 |

| Actual demand and supply | = 270 | 270 |

If loans are given to industry for working capital –for example 40– and money is created, equilibrium will continue provided that there is compensation between these sections or all of them with the whole that is comprised of actual supplies and demands. Suppose the creation of money was 80, the example would be:

| Demand | Supply | ||

| Purchasing power | Merchandise | ||

| Disposable funds | |||

| Production | 300 | 300 | |

| Increases in stocks of sellers | – 30 | ||

| Increase of disposable funds of buyers | 70 | ] → 30 | |

| Loans for working capital | 40 | ||

| 110 | – 110 | ||

| 190 | 270 | ||

| Creation of money | + 80 | ||

| Actual amounts | 270 | 270 | |

In principle, loans for working capital cannot be added but, conversely, subtracted. As mentioned, it does not represent a demand but an internal permutation of funds. The result is 190 demand compared to an actual supply of 270. There will be disequilibrium, if money is not created –which has occurred– at a value of the difference of 80. Bernácer will never stop repeating that the creation of money is required to finance working capital so that the market is balanced. This is a key argument in his thought.

For the same reason, when these last amounts –creation of money and financing of working capital– are not compensated for, disequilibrium will survive.

305 in demand is greater than the 295 of supplies, and demand is greater than supply by 10, which is the number in the penultimate box on the right below, allowing Assets and Liabilities to be made equal.

The conclusion that Bernácer draws from this is as follows: Excess working capital from the loans for working capital will cause disequilibrium in favour of demand. These types of elementary explanations are detailed in Bernácer’s monetary theory with a series of exact and strict formulas that are quite complex, truth be told. However, I believe that the explanations given here may be clearer and easier to understand, preparing readers for the subsequent ideas expressed about monetary theory.

| Demand | Supply | ||

| Production | 300 | 300 | |

| Period increases | 10 | – 5 | – 5 |

| Loans for working capital | 15 | – 25 | |

| 275 | 295 | ||

| Increases in money | 30 | 10 | |

| Disequilibrium in favour of demand | 305 | 305 | |

Let’s continue with another example. We will start by looking at the total monetary resources received by companies:

| Monetary fund of companies at the start of the period .................. | 400 |

| Amount of period sales .............................................................. | + 305 |

| Loans received for working capital ............................................. | + 15 |

| = 720 | |

| Income and wages paid (cost headings) ...................................... | – 300 |

| Resources available at the end of the period ........................... | 420 |

Now let’s look from a viewpoint of production and sales or supplies and demand:

| Stock of merchandise at the beginning ...................................... | 500 |

| Production ............................................................................. | + 300 |

| Total ..................................................................................... | 800 |

| Value of sales (not sales price) ................................................. | – 295 |

| 505 |

What do we know at this point? That companies have more money, 420, and while it is not otherwise stated, this is working capital. There is merchandise worth 505 at the closure of the period.

Relating the money and merchandise that companies had at the beginning with the money and merchandise they have at the end, the increase in working capital is obtained. In turn, this increase will be compared with the financing of this capital, financing that is calculated by related loans and by profits.

WORKING CAPITAL

| Beginning | End | |

| Money | 400 | 420 |

| Merchandise | 500 | 505 |

| 900 | 925 |

Thus, the increase in working capital is 25 = (925 – 900).

| Loans for working capital | – 15 | |

| Increase in working capital | 10 | |

| Working capital | 900 | 925 |

| 910 | 915 |

This could be summarised as: the increase in working capital is 25, while the financing for this working capital is 15 and thus the difference is 10 in favour of demand.

This difference is an operating surplus, which originates due to buyers giving purchasing power to companies, 10 more than sellers have delivered through income contained in the articles sold.

4.6. Resales and realisations

Frequently, products are bought and sold on the market that have not only been produced and sold, but have also been the object of subsequent buying and selling operations. Two types of goods are the object of these transactions: one is semi-durable consumer goods like books, jewels, noble metals, antiques, etc. The others are goods that generate income due to owning them (non-production) like a rental property, bond or security. Both the first and second group of goods is the object of buying and selling on the market. Transactions in the first group are called resales and in the second group, they are called realisations.

Let’s analyse resales. Some products were already sold and demanded and are then supplied again and, consequently, demanded again. This merchandise –that is not new production– enters once again into potential market supply and has a quantity of purchasing power, passing into the hands of buyers, modifying potential demand.

These operations do not change price levels of current production, but their consequences can change the market, since they require resources to carry out these transactions that could come out of potential demand and affect new production. New production means new wealth and new production income, while old production does not. If old production prevails over new, the potential production capacity of the system will be decreased. Normally, these operations are not harmful to the system. However, realisation operations are indeed harmful in the financial market, on which income assets are traded, or our financial assets. Shares, securities and other secondary financial assets, such as properties, lands, constructed buildings, property rights and credit instruments, are the object of innumerable buying and selling transactions, which Bernácer called realisations. These operations are dangerous because they are fed by disposable funds and are non-invested savings, whenever of course new money is not created for these purposes. If new money is not manufactured, goods and services will not be manufactured either and income will not be generated, given that part of the income that emerges in parallel with current production will have been usurped by realisation operations.

Resale and realisation operations in themselves do not alter the magnitudes of the purchasing fund or the existence of articles on the market, but the same quantity of money changes hands for the same quantity of goods. There will be different consequences that occur in future periods.

4.6.1. The mathematical expression of market equilibrium

The mathematical operations used in Bernacerian macroeconomics don’t go beyond addition and subtraction and are therefore simple. There may be an integral or two used in working with prices, but there is generally nothing of greater complexity.

The value of the product obtained will be equal to the whole of payments generated. Thus, all production generates income, which is the same as saying that all income comes from production19. Therefore, savings, the issue dealt with here, has its equivalent in a part of previous production. This is true in non-monetary economics and monetary economics.

It is true in monetary economics because savings, which is money, is represented in sold merchandise, merchandise that is national product. Therefore, all savings must be equal to investment, which is spent on capital goods or, in other words, is the production that remains after having spent part of the income on consumer goods. One needs to exercise great tact with this statement made 11 years before Keynes’ General Theory in which he expounds that savings is equal to investment (S = I), an identity so highly criticised by Bernácer.

P is the total value of production, R the value of payments or income and d the value of what is demanded (don’t confuse this with disposable funds, denoted by D) or the value of the purchases made on the market. T is the period between two moments a and b20.

P = R whenever Say’s Law is fulfilled potentially and theoretically. The value of stock at the beginning and end of the period will be respectively E and E’; A and A’ will be the unspent income that is available at the beginning and end. As they are not spent, there is unsold stock, and d will be different than P, because everything produced was not sold. This difference is explained and are analysed in The Interest of Capital (1925).

1) In the beginning at point a, there are goods that have been demanded in the period ab; therefore they will be found in the value of d, and E and must be eliminated by subtracting d – E.

2) P includes products found at the end at moment b. Thus, they must be eliminated by the difference P – E’.

From 1) and 2) the part(s) that are common to both P and d are obtained (common but not equal). Thus:

d – E = P – E’, and isolating P:

P = d – E – E’ or also P = d + (E’ – E)

To express this phrase commonly, it says: ‘production is equal to what is demanded plus what remains or that which is not demanded’.

E’ – E is the value of unsold stock represented by ΔE.

So P = d + ΔE.

Savings is the part of income R that is not spent. Why will R be different than d? For the following reasons:

1) Because d is a demand that may have been fed from previous resources and is found at the instant a.

2) Because R includes payments that may not be spent in the period T between the two times ab.

That which is still not spent at time a is A’ and that which is unspent at time b is A’ as mentioned. So, the difference A – A’ will indicate the part that is spent or not spent depending on whether it is negative or positive. Then it is agreed that: d – A is equal to demand minus what remained at the beginning and R – A’ is the part of income that wasn’t spent, so that the terms will have a part in common and therefore:

d – A = R – A’

which means that net demand is equal to the net part of income spent, which has the same meaning. Then:

R = d + (A’ + A) → A’ – A = ΔA

then

R = d + ΔA

an expression that when commonly interpreted means that income is equal to the value of what was demanded plus what wasn’t spent or saved. Therefore:

d + ΔE = d + ΔA (because R = P) and thus ΔE = ΔA

This means that as people don’t spend and liquid savings are formed, there will be a quantity of unsold merchandise. If there is greater spending and lesser savings A, in parallel there will be a lower quantity of merchandise E that is unsold.

As you will see, macroeconomics calls this part of E nothing less than inventory investment, thus violating the fundamental equation or identity of macroeconomics: S = I. Observe that demand d21 includes consumer goods, which you already know, as well as capital goods. Demand for capital goods is called investment. What Bernácer wanted to stress from the beginning is that savings comes from equivalent production and due to this, it is equal to this unsold production and that which is really sold.

At the risk of seeming repetitive, I repeat that there is nothing more complex to Bernácer’s logic. As people save more, this means that their disposable funds will have increased by ΔA, and while the converse is not true and this savings is not invested, the parallel consequence is the increase in stock ΔE. ‘A’ comes from income and E comes from production and, in turn, income R is born from production P. Then, in order to bring the entire market into balance, previous unsold production and previous unspent income are both added.

5. Market terms in mathematics

5.1. Introduction

Bernácer carried out a comprehensive and thorough analysis of economic phenomena, providing extraordinary detail. These phenomena are transactions made by different agents always using money against goods. Money and goods have different names in traditional and Bernacerian symbology, given that they derive from concepts that are also different.

These operations and things have a specific nomenclature, which does not coincide with traditional macroeconomics, but be warned –it is advisable to move with caution here– that this lack of similarity is double: one superficial, with respect only to the letters employed. Thus, production is not Q but P (P is prices in traditional macroeconomics) and the other refers to concepts.

Without these mathematical rudiments, it is still possible to understand Bernácer’s economic logic, but it is better to express it here in its entirety so that you can understand it well enough.

5.2. The symbology

Macroeconomic symbols:

Total national income: R

Total value of production: P

Potential demand: dp

Actual demand: d

Potential supply: Op

Actual supply: O

Company operating surplus: β

| At the beginning | At the end | Variations | |

| Amount of working capital | m | m’ | Δm = m’ – m |

| Clients’ money | A | A’ | ΔA = A’ – A |

| Companies’ money | c | c’ | Δc = c’ – c |

| Merchandise stock | E | E’ | ΔE = E’ – E |

| Working capital | K | K’ | ΔK = K’ – K |

| Fixed capital | X | X’ | ΔX = X’ – X |

| Loans and transfers from funds To companies | Z | Z’ | ΔZ = Z’ – Z |

| Loans for working capital | H | H’ | ΔH = H’ – H |

As seen in the last chapter, potential supply and demand will be expressed by:

dp = R + A + M

Op = P + E

Actual demand and supply will be expressed:

d = dp –A’ – H’ = R + A + M – A’ – H = R – (A’ – A) + ΔM – ΔH =

= R – ΔA + ΔM – ΔH

Moreover and according to (1)

O = Op – E’ = P + (E – E’) = P – (E – E’) = P – ΔE

As said, potential market balance dp = Op, is different from real or actual balance de = Oe. This last balance would mean:

R – ΔA + ΔM – ΔH = P – ΔE

and taking into account that R = P, we have:

ΔA – ΔM + ΔH = ΔE

For the particular case that ΔM – ΔH = ΔE, that is, when the increase in the quantity of money is equal to loans for working capital, then:

ΔM = ΔH

ΔA = ΔE

and in virtue of that:

ΔM = ΔA + Δc

ΔK = ΔE + Δc

then

ΔM = ΔK = ΔH

This equality expresses Bernácer’s equilibrium or the conditions for equilibrium. Expressed more simply:

‘In a balanced state, the increase in companies’ working capital is equal to loans for working capital and also equal to the amount of money created…’ (Germán Bernácer, A Free Market Economy…: page 230).

I believe that expression could be better as follows:

‘For balance to exist, the quantity of money created must finance the loans for working capital, which in turn must finance increases in working capital by the same amount’.