Appenix |

|

Appendix 1: Symbols and clarification of certain nomenclature

It is normal in economic terminology to use specific letters and terms, which due to their repeated utilisation over time and in economics textbooks, have become familiar to readers. Since I have respected Bernácer’s original terminology, which is different than the traditional terms, I have clarified the meaning of the terms repeatedly to avoid confusion.

| Traditional terminology: | Bernacerian terminology |

| C: consumption | R: production income |

| I: investment | R: speculative income (as I will clarify in each case) |

| Y: income | O: supply |

| Q: value of production | d: demand |

| PNNcf: net national product at the cost of factors | A: disposable funds |

| i: interest | E: stock |

| D: demand | K: working capital |

| p: prices | M: amount of money |

Z: money proceeding from savings directly to entrepreneurs | |

H: amount of working capital employed | |

z: amount of fixed capital employed |

Note: After setting forth traditional macroeconomic expressions and symbols and then those used by Bernácer, I would like to make the following clarification:

The expressions and equations have been respected as Bernácer set them forth. Now, following his thought, I speak of disposable funds, income, interest, and for greater comfort, I have expressed them as follows:

| d: | demand | |

| D: | disposable funds | |

| R: | Income, which is valid for production income and income derived from income-yielding assets, always pointing out which one is in question. However, understanding should be clear from the context of the phrase or equation. | |

| S: | Will always be savings | |

| Sk: | Will be the part of savings that is capitalised | |

| S: | Sk + D is an important expression that tells us the destination of savings, capitalisation Sk or investment in disposable funds. | |

| I: | investment | |

| i: | interest | |

| P: | is the price level. However, when I textually quote Bernácer, it means production. In all other cases it will be prices. | |

| Bernácer said O = R, which means that production is equal to all income generated. It is equal to the conventional terminology of Y = PNNcf |

If readers wish, you may skip Bernácer’s arithmetic explanations, which are somewhat complex, and simply read the verbal explanation. You could read the introduction and conclusions only if you like. With respect to formulas, it is enough to know my symbols of: S, Sk, D, i, R (non-productive income).

Abbreviations used in references to works:

Bernácer:

Society… from Society and Happiness: Essay on Social Mechanics

The Interest… from The Interest of Capital: The Problem of its Origins

The Functional Doctrine… from The Functional Doctrine of Money

A Free Market Economy… from A Free Market Economy without Crisis or Unemployment

Keynes:

Treatise… from Treatise on Money

The General Theory… from The General Theory on Employment, Interest and Money

Appendix 2: Dictionary of bernacerian terms

(or related terms)

Savings: Monetary flow that is part of income and is not consumed.

In a precise and strict sense, savings comes from prior production. This premise and reality can be used to admit traditional economists’ claim that S = I.

Amortisation: Accrued savings that are used to replace the wear and deterioration of capital goods.

It is a phase of an active operation, in the sense that it involves the change from one type of disposable fund –savers– to another disposable fund –producers– (even if the producer and saver are the same individual).

Hoarding: Part of non-consumed income and, therefore, part of savings that is taken out of circulation and does not demand capital or consumer goods. Neither does it involve a demand for financial assets.

Capital: Durable goods that aid producers in production tasks. Bernácer acknowledges the existence of durable goods that do not necessarily aid production, but that do however generate a chain of utilities over time. He calls these consumption capitals and they do not necessarily or not totally match up to those called semi-durable goods in traditional economics.

Fixed capital: The previous explanation can be used here as well. Liquid or net capital is the sum resulting from subtracting amortisation from total capital. Its recovery through amortisation is extremely important. Both of them are active operations.

Working capital: Concept derived from business economics, consisting of supplies of goods and services being revalued during the production period.

Bernácer was interested in showing that merchandise produced is working capital, even when this merchandise is capital equipment (or fixed capital). For producers, fixed capital ‘is working capital just like the wood for the cabinetmaker or flour for the mill owner…’ (A Free Market Economy, page 31).

When demand unleashes its purchasing power, the producer releases his manufactured machine and, after it is in the hands of the party who is going to use it, it will be called fixed capital.

Working capital, financing: Working capital will be financed with new money and fixed capital with savings. Financing working capital with savings is depressive.

Capital, financing: Capital is financed with system savings, thus guaranteeing macroeconomic equilibrium and the fulfilment of the equality S = I.

Financial capital: Meaning given to savings and its financial materialisation.

Liquid capital: Concept stressed by Bernácer to criticise the theory of interest, pointing out the difference that needs to be made between capital and the monetary flows that finance it (many economists confuse the terms).

Actual capital: He used it to differentiate the misnamed financial or simply monetary capital. Real capital is simply capital (fixed and working).

Capitalisation: Employment of savings to acquire capital goods, produced spontaneously by companies, or to finance building capital goods when taking place at the initiative of savers or those who cede their savings.

Capitalisation and production: Companies create products, adding value. This operation is production, even when the product is capital equipment.

Capitalisation is a financial operation that lets capital goods be financed with savings.

Capitalisation and realisation: Capitalisation is an operation utilising demand (of capital) for new capital goods (both net and replacement).

If the same capital equipment is bought and sold several times, it is no longer capitalisation but realisation. It is used for current assets. In realisation, the market does not eliminate the good that continues as supply.

Cycles: Periodic fluctuations of national income and production owing to the reciprocal interaction between the real and financial markets, real profitability and financial interest and aided by the institutional rigidity of systems, such as the gold standard, fixed exchange rates, rigidity of salaries, etc.

Monetary circuit: Channels through which money circulates in the production circuit. The payment of wages and salaries makes money move from producers to consumers and when consumers buy, money moves back to producers. Since a financial market exists, the money circulates both ways in a single circuit and is comprised of two sub-circuits: the ordinary market and the financial market.

Types of working capital:

1st class: Money required for the payment of incomes and product acquisition (value of national product).

2nd class: Required for payments between companies in the production process chain.

Companies continue to successively incorporate added value until the final product, which is the sum of the final added value. This is also national product: 1st-class working capital. Moreover, companies buy all production from the previous company, adding their value and selling it on to the next company. The total of all these payments is 2nd-class working capital.

Bank credit and working capital: The process of forming short-term working capital in the company’s activity period. It is normally an offshoot of bank credits (discounted notes). Apart from this, a condition of macroeconomic equilibrium requires that working capital is financed with new money.

Crisis: It is a sporadic accident of depression. It is not necessarily the inflection point between prosperity and depression. A state of latent tension.

Bank account for working capital: In monetary regulations, there must be an account for financing working capital, which will be fed by new money (granted by banks).

Disposable income accounts for fixed capital: Monetary regulation to achieve dynamic equilibrium. The fixed capital account will receive savings from the system and company savings, along with amortisation. It will never be used to finance working capital.

Actual demand: Demand and purchases made of consumer goods and capital goods in a specific time period. In this way, money moves from consumers and producers to the final producers.

Financial demand: This is the potential or actual demand that gravitates over the financial market to absorb financial assets (and real, secondary ones). Financial potential is equal to the maximum disposable funds in the system. Effectiveness means the purchases made on the financial market. For methodological comfort, the money created will be considered as accruing in disposable funds, when this money is lent or earmarked for speculative aims.

General demand: All demands really executed on the general market. It is therefore actual demand plus demands executed in the financial market. And therefore, it represents demand for consumer goods, capital goods and financial assets.

Potential demand: The total demand capacity existing on the market. Hypothetically, to achieve equilibrium, it must coincide with total income, which in turn, equals the monetary value of production.

Depression: Descending zone of the cycle. A drop in national income and a decrease both in savings and in investment.

Discount of future utilities: Bernácer’s criticism of Böhm-Bawerk’s psychological theory on interest, based on the discount of future utilities.

Market disequilibrium: Refers to the ordinary market, when the income coming from the market is not demanded from it. If the opposite occurs, the consequence is an increase in prices.

Money: ‘Money, whatever form it takes, is the symbol of a credit against society’ (The Functional Doctrine, page 27).

Money, purchasing power: The basic function of money. ‘If this were not true, it would lose all its utility.’

Money, intangible nature: Right to reclaim its value.

Money from the ordinary market: Comes from the ordinary market as payment for factors of production and part returns to this market through buying and selling. The other part goes to the financial market.

Disposable money: Please see disposable funds.

Financial money: With money, there is also traffic with real, dead wealth and financial wealth (secondary). It is possible for a financial instrument to be used as money, which alters circulatory mechanics. It is possible that commodity money, like gold, is used as a financial instrument, which then depresses the economic system.

Disposable fund: Fraction of income that, having avoided consumption, is not earmarked for demanding capital goods (it is not invested). It remains in this state to go to the financial market to demand assets on the secondary sector of this market. As a whole, buying and selling operations on the financial market do not mean a loss of disposable funds for the system and therefore entail a renunciation or loss of capitalisation.

Disposable funds, first-degree or minimum or consumers’: In the hands of consumers, they translate into consumption and disappear as disposable funds.

Disposable funds, second-degree or producers’: In the hands of producers. They are needed to continue production, thus disappearing as disposable funds.

Disposable funds, maximum or third-degree from savers or capitalists: See general definition for disposable funds. The net flow of disposable funds that remain among those that are input and output, I have called these net disposable funds (Bernácer however did not use this name).

Disposable funds, net: Disposable funds in the strict sense or third-degree.

Complete market equations: Arithmetic expression of market equilibrium. It is a dynamic balance that lets the step from a static economy in which S = I be expanded to the economy that is found growing through working capital. Out of this working capital, part is comprised of fixed capital in the hands of its producer and its creation must be financed with new money.

Companies, financial regime: Conditions set forth by Bernácer to achieve dynamic equilibrium.

Desired cash balance: Or encaisse désirée, a term coined by Walras, that in Bernácer’s judgement, hides the supply and demand of goods.

Market equilibrium: Situation in which overall supply and demand are equal. Since the beginning (1916), Bernácer admitted equilibrium in a situation of unemployment. Full employment equilibrium for Bernácer required, above all, the disappearance of the financial market.

Financing: Payment, demand or purchase of fixed capital with savings and working capital with new money. It is a part of actual demand. Financing is a purchase.

Fund: Term comparable to disposable fund. Nonetheless, it does not represent this category when speaking in other economic terms. There are acquisition funds, product funds (includes salary funds, lendable and available, when referring to the disposable funds of consumers, producers, capitalists, savers, etc.).

Identity: Cited for tautology. It creates confusion because either two things are originally different so that the identity is excessive or they are the same thing with two names, in which case the identity is superfluous as well. Thus Y is income from production O and from this, Keynes did not say that it was an identity (quote by Bernácer).

Identities: Bernácer criticised the macroeconomic identities Y = C + S; PN = C + I and S = I. The only thing that is true is that Y = PN, which expresses potential equilibrium or Say’s Law. In economics, identities would have to include disposable funds on the income side and financial assets in supply. Bernácer’s equations or identities would be:

Production: Production of consumer goods + Production of capital goods = consumption + capitalisation + disposable funds, then:

Savings = income – consumption and therefore,

Savings = capitalisation + disposable funds. Expressing the above in symbols, Sk is invested or capitalised savings and D are disposable funds and thus: S (total savings) = Sk + D

Disposable funds D represent non-executed demand and demand realised in financial assets, then disposable funds must be brought into relationship with inventory investments (unplanned). Remember that all disposable funds are net.

Interest: The price of money.

Interest, current: The money market interest rate. It is the interest that necessarily comes from the financial market.

Interest, dichotomy of: Current interest that depends on the supply and demand of money. On what money? Loanable funds, or disposable funds or noncapitalised savings, on the one hand. On the other hand, normal or real interest (Wicksell) determined by the real productivity of capital. For Keynes, this would be the marginal efficiency of capital.

Interest, monetary and financial: My proposal to finish Bernácer’s theory. With disposable funds D, income-yielding assets V are acquired that let the income R be determined, with interest thus growing. D is non-capitalised savings. In this book, this is financial interest, called current, monetary or market interest by Bernácer, Keynes, etc.

The other part of savings, specifically that which is capitalised Sk (S = Sk + D), is the object of supply and demand, a phenomenon that takes place on the ordinary market (not the ordinary money market). This is the monetary interest rate.

There are two types of interest: monetary and financial.

Interest, origin of: Monetary interest is equivalent to the interest called current.

It is the interest that appears in the economy. It is born on the financial or income-yielding assets market. These assets generate income R that, related to its market price V, lets the percentage yield be determined.

Since these assets (income-yielding) are acquired with disposable funds or non-capitalised savings (S – Sk = D), interest will indicate the profitability of that non-capitalised income, understood as a deterrent to production.

Interest, origin and calculation: The market determines the value of the market price of securities, V, and the income R is known, the interest or percent yield can be found. The formula will be i = R/V.

Interest, unification of: There is practically only a single interest rate… ‘because the yield of all stock-market securities tend to come into line within the risk differences that marginal fund placement agents attribute to them. All of this unification, within the diversity, occurs on the financial-money market.’

Interest and savings: Savings would form even without the existence of interest (criticism of Böhm-Bawerk).

Keynes: British scientific economist who is famous internationally. He created and formulated a new concept of the economy, based on a theory of interest, connected to a model for the determination of income (equilibrium with unemployment). The similarity with Bernácer’s body of work (published earlier) is enormous.

Liquidation: Operation of producers selling current assets to consumers. Here, demand is released to market supply.

If the producer sells to another producer (either current or capital goods), it is called realization and this intermediate demand does not unload market merchandise.

It is said that working capital is continually liquidated, although this is not true of fixed capital.

Liquidity: Capacity of certain assets to be converted into money. Includes money itself. Liquidity includes money and other assets. It belongs to banking and speculative terminology.

Liquidity, preference for: Desire to keep liquidity. Preference for money over other things without this condition. What condition? Immediate purchasing power.

To Bernácer, liquidity preference hid the old concepts of supply and demand for speculative goods and assets.

Liquidity and disposable funds: Liquidity is a Keynesian term and disposable funds are a Bernacerian term. Liquidity is money and also other assets. Disposable funds are less than money, since it is only that part of income that is neither consumed nor invested.

Financial market: Place where the supply and demand for income-yielding assets and actual secondary financial assets are found. Neither national product nor production income (Y = national income) are created here, but rather speculative income R. Savings is not channelled to investment here.

Capital market: Place on which the long-term supply and demand for money are found. It is confused with the capital goods (factors of production) market. According to Bernácer, classical and neoclassical economists confused money both terminologically and conceptually. They equated it to capital goods, but it is really used to demand these capital goods.

Income or Financial market: Like consumer assets that are acquired for the services they provide and capital goods are acquired for the chain of returns they generate, income-yielding assets (Robertson coined the previous phrase, correcting Bernácer who simply called them income assets), financial assets are bought and sold for the units of income they produce.

Since the updating of a chain of perpetual and infinite incomes over time is equal to R/i, which is equal to the value of this income-yielding asset (or simply financial asset), financial market and income market are used synonymously 169.

Ordinary market: Place on which the supply and demand for goods and services are found. In this market, the goods that are offered are manufactured; generating incomes that inevitably and necessarily are potentially equal (potentiality in Say’s Law).

Financial merchandise: Financial assets or income-yielding assets. Actual assets that represent traffic from former production cycles are included here.

Irreproducible merchandise: Products that cannot be reproduced due to their nature. Paintings by great artists, land, etc.

Ordinary merchandise: Consumer and capital goods.

Financial supply: Supply of income-yielding or financial assets on the financial market.

The supply of income-yielding assets is considered equal to the units of income supplied on the market.

It tends to be elastic considering the enormous possibility for creation and different arrangements. A house (actual asset) that was produced in the past and is suddenly offered represents a new financial supply (financial in the sense I have used). The quantity of profitable assets is much higher than liquid funds (disposable funds) in existence. During emergencies, this circumstance causes their market prices to fall quickly, with interest rates increasing greatly.

Opposite this elasticity of supplies of financial assets is the enormous capacity of the central bank and/or private banks to create money.

Paying is owing: Bernácer’s phrase when speaking of the creation of cheques, the exchange of money for merchandise on the market. There may be more production and more merchandise and no more physical, institutional creation of money. Currency, whatever form it takes, is a credit against the market.

Thought and action: Economic science is the science of facts, not thoughts. These are valuable as long as they are translated into action. ‘Psychological factors are not economic factors, which determine action, conditioning and regulating action, but as soon as this happens, economic phenomena arise.’

Prices, of the authorities: Taxes. They are arbitrary and distort reality. Even in times of disorder, prices are produced on the market at the meeting point between supply and demand. Authority prices are wrong for two reasons: because they rule out gradual adjustments of the market and because they make all market information that free prices engender be lost.

Prices, unit of income: Quotient between actual monetary demand on the financial market and the units sold or traded. In other words, the quotient between what has been paid for a purchase on the financial market and the units of assets bought on the financial market. Stated more directly, how much a financial asset costs:

P (price of the unit of income) = D/N

(amount of demand)/

(number of units traded)

Prices, market: Result of voting on the market using money. ‘They are elections where you vote with money, not with ballots’ (A Free Market Economy, page 84). It is a social event, the result of a set of desires and free choices. ‘A free market is the most perfect expression of democracy’ (page 83).

Loans to producers: Loans to producers from savers. It does not represent part of actual demand. Money is also received through sales, but they are not loans.

Productivism: Erroneous theory about the origin of interest based on the productivity of capitals. Since money was offered to acquire capitals, and capital was used for production, productivists thought that the origin of interest was here. It is the antecedent of Wicksell’s real interest and Keynes’ marginal efficiency of capital.

Property: ‘The existence of private property seems to me like a fact inherent with freedom’ (A Free Market Economy…, page 187). We can only have access to property through labour and savings and the only form of property is capital or, in other words, the fruit of labour. Bernácer prevented free rent from being received without working by the mere fact of keeping a property, an asset.

Land ownership: Historically led to interest. The financial privilege of the bourgeoisie gave rise to the origin of interest on capital (remember that income R, in this case by Ricardo, will be R and the price of the land V, then the quotient R/V tells us the profitability of the market price percentage or interest).

Realisation: Mentioned earlier. Passive operation that does not spawn income or production. Sale to another intermediary producer of an already-created good.

Monetary regulation: Requirements that private banking and companies must follow to achieve dynamic equilibrium (with growth). It consists of the practice of periodic balance sheets, which let them know the calculation of savings operations and the needs for working capital and, therefore, for new money.

Income, speculative: Also called income from financial market assets. This income is not earned and is born by simply owning actual secondary financial assets. This is non-productive income (opposite to production income). It is born on the financial market and lets interest be calculated as the quotient of the amount of disposable funds that acquire the value of securities and other assets.

Income, productive: It is born on the ordinary production market. Production will engender an equivalent amount of income, entailing the potential fulfilment of Say’s Law.

Income from the land: The occupation of less fertile lands makes the operating cost more expensive and the product price higher (while the product price on more fertile lands will continue to be lower). This will provide the other lands (the most fertile ones) with greater benefits (for the land and for the landowner). Thus arose the term land rent, called territorial income or Ricardian income, because Ricardo developed the theory with great refinement.

This greater advantage is objective and transmissible (by income) and is an interest (i = R/V) applied to the active land and that can be enjoyed without working, by the simple fact of being the landowner (it is the tenant who works the land). Its utilisation will be on a level with financial assets, just that land income is ancient.

Profitability of executed or past capitalisations: Since they cannot be withdrawn, but are rather used up or depreciate, their value will be adapted to their profitability, with respect to what free capitals 170 normally produce whether devoted or not to industry at that time.

Profitability of planned or future capitalisations: They are carried out after being calculated where profits, corresponding to their market price, must at least compensate the current capitalisation rate.

Marginal profitability of capital: Percentage yield that is obtained from the capital employed after covering the costs of amortisation. Like the calculation of interest, here returns (net = gross = amortisation) are related to liquid assets (savings) employed, which is the value of the capital goods (r = yield K, where K is the value of capital equipment).

Robertson: English economist, related to Keynes, who brought Bernácer to the eyes of the international, scientific-economic community in an article published in Ecónomica in 1940. He maintained correspondence with Bernácer for many years and received, at the beginning of the twenties, the article on the theory of disposable funds.

Say: French economist, who expressed his théorie des débouchés, according to which any merchandise represents an output for the rest. Bernácer said that ‘This is confusing merchandise with money’. To Bernácer, Say’s Law is explained by saying that potential supply and demand are equal. This is a fatal and logical mistake. He said that Say forgot about money: ‘Money was created, among other things, so that Say’s Law could be better fulfilled’ (A Free Market Economy, page 298). But with money, financial assets are bought, which are not current wealth. Since this money, which is income, is born from production, a weakness in demand will develop.

Schumpeter: Austrian economist criticised by Bernácer. Interest would be a coefficient of technical advances in a dynamic economy. Technical advances increase the profits that the competition eliminates, but not with monopolies. He did not clearly present if the percent profit or interest is the result of the advance and/or of the monopoly. In any case, it is a remainder of productivism (read the productivism entry above) that says that, since capital can be acquired with money and then produce a return, then money entails a reward in the form of interest.

Olgario Fernández Baños espoused a similar theory, which Bernácer by extension also criticised.

Turgot: French physiocrat and economist currently recognised as one of the pioneers of monetary theories. Bernácer was inspired by him in his theory on interest. ‘Loans for interest is exactly a trade where the moneylender is a man who sells the use of money and the borrower is a man who buys it precisely like the landowner and his tenant respectively buy and sell the use of a rented fund.’ (The quote is by Turgot and cited by Bernácer in The Interest of Capital, page 96.) Saying that, like land and capital produce yields, if money is lent to acquire money, then this return is renounced, where this is the cause or origin of interest. This is false, because it presupposes the existence of that which is renounced, interest.

Turgot also distinguished between money that establishes interest (the price of money) and money that determines the high or low price of merchandise. The first is saved and the second earmarked for consumers’ current expenses. Turgot did not forget that money can be occupied in speculative or non-productive operations (Bernácer’s financial market). However, he did not place importance on this fact, thinking that the speculative period and this market were negligible. Turgot contradicted himself given that current money (Bernácer’s ordinary market) and reserve money (disposable funds from the financial market) were distinctions he himself created. Turgot’s theory is the antecedent of Bernácer’s demand for money and interest.

Value of money: Purchasing power. If prices go up or down, the value of money decreases or increases respectively. Just like the price of merchandise is established by money, the price of money is established in a market: the money market.

There are two prices of money: the price of money with respect to merchandise or purchasing power and the price of money that is the use of capital-money used to buy machines or capital goods.

Wicksell: Swedish economist who differentiated two interest rates: current or monetary and natural. He also related these two to explain the economic cycle. To Wicksell, the monetary interest rate resulted from the supply of and demand for money and the natural rate would be somewhat similar to the real productivity of capital in general in an economic system. His theory used Ricardo’s ideas, for whom interest determined the quantity of money and the quantity determined price levels. Bernácer, who had scrupulously studied the history of economic thought, especially the theory on interest, was not aware of (or so it seems) Wicksell’s use of Ricardo’s ideas. Although Bernácer travelled through Europe for several months and knew languages like French and English, he did not know about Wicksell’s theory, which was unknown in the world for many years. Wicksell is the most similar and recognised predecessor to Keynes, due to relating interest rates to the profitability of capital (marginal efficiency of capital).

Appendix 3: Opinions on the functional doctrine of money by Germán Bernácer

Antonio Montaner, economics professor at the University of Maguncia (excerpt from an article published in the magazine Kyclos, Berna):

‘Bernácer’s book on Monetary Theory provides a valuable summary of the work of this important Spanish economist in the special field he sows, whose theoretical research and explanations (like Rudolf Stucken said correctly in summary) are very suitable for falling into stasis, because they do not give, always and everywhere, specific ideal premises that are political or institutional’

Henri Wallich, economics professor at Yale, in The Review of Economic Statistics (excerpt from the review):

‘Mr Bernácer has brought together his entire theory, previously dispersed in numerous articles, into a single volume entitled The Functional Doctrine of Money. The first part contains the exposition of the doctrine and its increasingly-complex technical execution. The second part is devoted to analysing the work of contemporary Anglo-Saxon economists and to a discussion of several points related to the doctrine. The book, not free from difficulties, reads well and brings to mind the charm of Böhm-Bawerk in many points.’

Virgil Salera, professor in Miami (Florida) in The American Economic Review:

‘Those studying monetary economics would do well to consult this volume, given that virtually the entire Keynesian model is subjected to critical research and, at times, highly suggestive. There are also several interesting critical commentaries about the central features of the writings by Hawtrey and Robertson…’

The comments by D.H. Robertson and G. Haberler could be added that were made in the magazine Económica (1940) and in the Spanish edition of Prosperity and Depression, respectively. However, they have been cited at other points in the book.

Appendix 4: General exposition of works by Bernácer, Keynes &others (chronologically)

| Bernácer | Keynes | Other authors | |

| 1883 | Bernácer was born | Keynes was born | Schumpeter was born |

| 1893 | Wicksell: ‘Value, Capital and Rent’ | ||

| 1896 | ‘Theoretical Analysis of Finances’ | ||

| 1898 | ‘Interest and Prices’ | ||

| 1911 | Fisher: ‘The Purchasing Power of Money’ | ||

| 1913 | ‘Indian Currency and Finance’ (B) | ||

| 1915 | Robertson: ‘A Study of Industrial Fluctuation’ | ||

| 1916 | ‘Sociedad y Felicidad’ (B) | ||

| 1919 | ‘La Moneda y las Cuestiones Sociales’ | ||

| 1920 | ‘The Economic Consequences of the Peace’ (B)‘A Treatise on Probability’ | ||

| 1921 | ‘Dos Cuestiones de Actualidad: La Ley del Banco y del Arancel’‘El Problema Monetario’ | ||

| 1922 | ‘LA TEORÍA DE LAS DISPONIBILIDADES’ | ‘A Revision on the Treatise’ | |

| 1923 | ‘A Tract on Monetary Reform’ (B) | Hawtrey: ‘Monetary Reconstruction’ | |

| 1924 | ‘Discurso sobre los cambios’‘La Teoría del Problema Social’ | ||

| 1925 | ‘Interés del Capital…’ (B)‘Nuevo Discurso sobre los Cambios’ | ‘The Economics Consequences of Sterling Parity’‘A Short View of Russia’ | |

| 1926 | ‘Ciclo Económico’ | ‘The End of Laissez Faire’‘Laissez Faire and Communism’ | Robertson: ‘Banking Policy and Price Level’ |

| 1928 | ‘El Cambio, el Comercio Exterior y la Balanza de Pagos’ | ||

| 1929 | (Stock market crash in United States) | ‘Can Lloyd George do it?’ | |

| 1930 | ‘La Depreciación de la Moneda Española’‘La Cartera de Fondos Públicos en los Bancos Centrales de Emisión’ | ‘A Treatise on Money’ (B) | |

| 1931 | Khan: ‘The Relation of HomeInvestment to Unemployment’Hayek: ‘Prices and Production’ | ||

| 1932 | ‘Essays in Persuasion’ (B) | ||

| 1933 | ‘Análisis de la Demanda y Síntesis del Mercado’ | ‘Essays on Biography’‘The means to Prosperity’ | Kalecky: ‘An Essay on theTheory of the Business Cycle’Haberler: ‘The Theory ofInternational Trade’ |

| 1934 | ‘Etiología de la Crisis’‘Génesis y Peripecias del Ahorro’ | ||

| 1935 | ‘La Teoría del Mercado Financiero’‘Moneda y Ciclo Económico’ | ||

| 1936 | ‘Sed de Oro’ | ‘The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money’ (B) | Haberler: ‘Prosperity and Depression’ |

| 1937 | Hicks: ‘Mr. Keynes and theClassics: A Suggested Interpretation’ | ||

| 1939 | Hayek: ‘Profit, Interest and Investment’Schumpeter: ‘Business Cycles’ | ||

| 1940 | ‘How to Pay for War’ | Robertson: ‘Essays on Monetary Theory’ (cited Bernácer’s work in the Spanish translation) | |

| 1941 | ‘La Teoría Monetaria y la Ecuación de Mercado’ | Hansen: ‘Fiscal Policy andBusiness Cycles’Hayeck: ‘The Pure Theory ofCapital’ | |

| 1942 | ‘La Expresión Fundamental del valor del Dinero’ | ||

| 1943 | ‘La Ecuación Monetaria en el Mundo Mercantilista’ | ‘International Clearing Union’ (speech) | |

| 1944 | ‘La Ecuación Monetaria en una Economía Capitalista’ | ‘Mary Paley Marshall’Keynes participated at Bretton Woods’ (Keynes plan) Creation of the IMF | |

| 1945 | ‘LA DOCTRINA FUNCIONAL DEL DINERO’ | ||

| 1946 | ‘The Balance of Payments of the United States’DEATH OF JOHN MAYNARD KEYNES | Samuelson: ‘Lord Keynes and the General Theory’Tobin: ‘Liquidity Preference and Monetary Policy’ | |

| 1947 | ‘El Déficit Presupuestario, la Inflación y Mr. Kalecki’‘Disquisición Keynesiana’‘Sobre la Concepción Keynesiana’ | Samuelson: ‘Foundation ofEconomic Analysis’Tobin: ‘Liquidity Preference and Monetary Policy’ | |

| 1948 | ‘El Bimetalismo. Revisión de su Causa’ | ||

| 1949 | ’Il Concetto di Stattico e Dinamico nell’Economía’ | Harrod: ‘The Life of JohnMaynard Keynes’ | |

| 1950 | Hicks: ‘A Contribution to theTheory of the Trade’ | ||

| 1952 | ‘Keynes, Kritish Gesehen’ | Baumol: ‘The TransactionDemand for Cash: An Inventory TheoreticApproach’ | |

| 1954 | ‘¿Cuál es la Corriente Monetaria que Mejor Conviene al Interés General?’‘Sparen, Capital und Zins’ | ||

| 1955 | ‘Teoría e Politica del Interesse del Capitale’ | Haberler: ‘A Survey ofInternational Trade Theory’ | |

| 1956 | ‘La Tendenze Restrictive nell’Economia Capitalista’‘El Sistema Financiero y las Crisis’ | Cagan: ‘The Monetary Dynamics of Hyperinflation’Hicks: ‘A Revision of Demand Theory’ | |

| 1958 | Tobin: ‘Liquidity Preference as Behaviour toward Risk’ | ||

| 1965 | DEATH OF GERMÁN BERNÁCER |

Note: The letter (B) in the columns for Keynes and Bernácer mean books. The rest are articles, pamphlets and conferences. All of Keynes’ and Bernácer’s publications are not set forth here, but only the most important ones. Bernácer’s works are set forth much more proportionally than Keynes’ works.

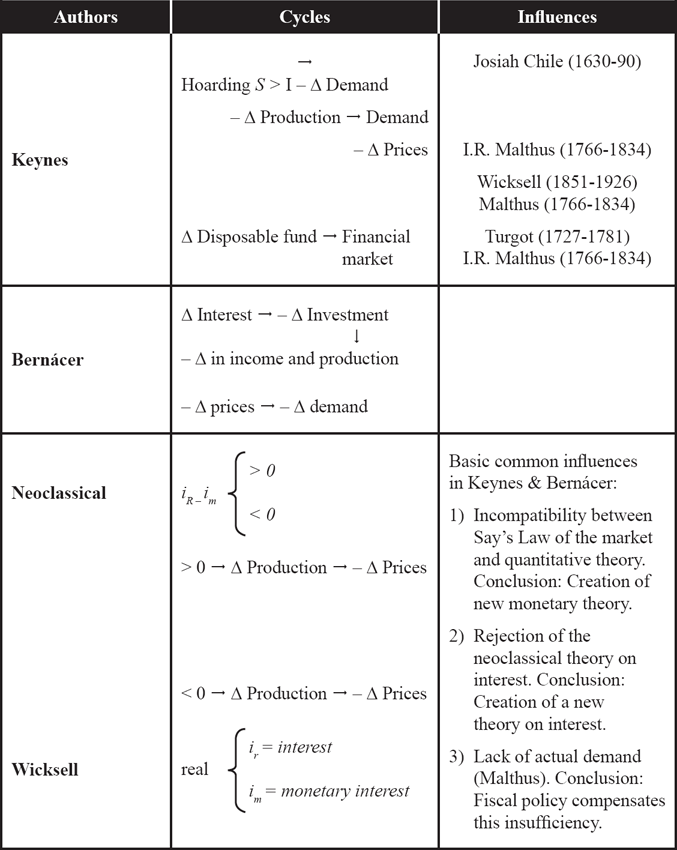

Appendix 5: Economic theories of Bernácer and Keynes: a general summary