26. The life and work of Germán Bernácer

26.1. My inspiration

Germán Bernácer Guardiola is the son of Germán Bernácer Tormo. He had just arrived from Chile, where he works as a technician for UNESCO and is a trained physicist like his father. Germán Jr came over to me and introduced himself. A white bridge of letter writing had brought us together. It was a sunny morning. I immediately took him to meet Emilio Figueroa Martínez, a retired professor of Political Economy and Germán Bernácer’s former student at the Business Studies School, as well as a technician in Research Services at the Bank of Spain, where Bernácer had been assistant director. Figueroa, who was partly handicapped and felt tense due to his excitement, met us at the door to his home – me and the son of the man and economist that he most admired. Clouds of memories rushed in. Thirty years had gone by. Both of them, with different emotional bridges, brandished their passions and wove together a brief history. The man, the extraordinary scientist that he was, had close relationships with both of them, and it enhanced memories when trying to form a biographical portrait. I looked on silently from a corner. And suddenly the oblivion to which our economist was subjected and the conspiracy of silence, referred to by Figueroa, dissipated.

Another day, an even sunnier day in the city of Alicante, I met Mrs María Guardiola, the widow of Bernácer, at her home, at German’s home. The paintings, of course, by Varela; the objects and furniture spoke a language from the past with voices cracked by melancholy. Her children, Eda, Germán, Ramón and Ana María, and her grandchildren accompanied María. Afterwards, I visited the small house on the beach ravaged by wind and sea. Several pine trees withstood the onslaught. The little house in the mountains, its internal and external structure changed, surely made its original state unrecognisable. It was beautiful, but undoubtedly deprived of its natural and ancient poetry.

With all of this baggage of data and figures hanging in disorderly heaps in the asymmetrical hollows of my memory, I began to write Germán Bernácer’s biography. The help provided by Oliver Narbona’s book, skilfully written and quite precise, as well as by the systematic, comprehensive and geometric book by unflagging Henri Savall, helped me organise my natural chaos. I was further assisted by the fact that I lived in Madrid and had retraced Bernácer’s footsteps step by step and had gone through archives and unorganised libraries. But above all by dealing with an invisible Cyclops: that of the indifference, the methodical indifference of many, and the conspiracy –if there was one– of dense silence, if not hostility. I do not know why Germán Bernácer continues to cause problems!

Moreover, it was very helpful to know what no one else knew, not even his family or Figueroa or Prados Arrarte or Henri Savall, which is that Bernácer is more important than they think. This secret that I have tried to yell out in the desert is what, surprisingly enough, in my impossible loneliness, has urged me on. The secret is that modern macroeconomics classes can be found in Bernácer’s work, work that has yet to be written. This is the secret, the drama and the glory of Bernácer and perhaps my own.

26.2. The early years in Alicante

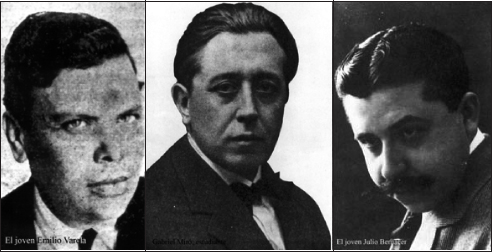

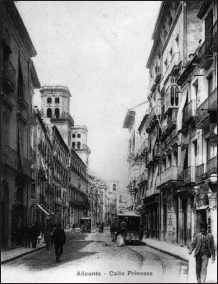

In the Mediterranean city of Alicante, in the restless year of 1883, Germán Bernácer Tormo came into the world on 29 June. For those that know the city, the exact place of his birth was number 10 of what is today Altamira Street, which used to be called Princesa Street. His father’s name was Antonio Bernácer Pérez and his mother’s Francisca Antonia Tormo Iborra. This was his father’s second wife, with whom he had two children, Germán and Julio 158.

Due to varying circumstances, the year 1883 was abundant in sowing many interesting people and events. In economics, this was the year that brought death to the prophet of the death of capitalism, Karl Marx, and birth to who, according to some, would save it: Englishman John Maynard Keynes.

Neither geography, nor science, nor education nor the restless stars in the sky propelled destiny; nothing, I say, to make these two infants appear who were determined to be born in the same year and obligated to repeat one another as twins in economic theories. As an invisible mirror in a Platonic universe, like the images of words said by others, whispers of Alicante were repeated in the hard crystals of the Levantine sky to illuminate and repeat what had already been said in the English mist, where an ancient race of giants – classical and neoclassical Englishmen – rocked the cradle of the sleepless Keynes.

Another man, a scholar of dynamic economics and an economics scholar to the fullest extent, was born this same year: Austrian J.A. Schumpeter.

Germán Bernácer in his late teens.

Bernácer’s mother devoted all of her efforts to the education and upbringing of her two sons, Germán and Julio, and her daughter, Isidora. The common seed, in the form of efforts devoted to education, intellectual and artistic stimulation, resulted in the two brothers having an insatiable appetite for the two branches of knowledge. Julio and Germán were born on different planets under the auspices of muses that were not remotely similar. Julio was a lover of words; he was emotional and subjective in his assessments. Germán was precise and rigorous in his observations; he touched what he saw and only believed in what he touched. Germán Bernácer was before anything, before even an economist, a vocational physicist, and it is known that phantoms of subjectivity do not play a part in physics. And their character traits were also opposite. Julio was always likeable and extroverted up to his early death in the thirties. He was a brilliant conversationalist, timely and wise, a skilled writer, lively and descriptive. He was possibly a seductive companion and an attractive person. Germán, on the other hand, was an introvert, discreet in his relationships, quiet and prudent. Maybe his most important trait was his crippling shyness, which made him appear untalkative –which was true– and perhaps unfriendly. His writing and literary skills were subjected to the millimetric rigor of the watchmaker, to the steadfast patience of the accountant, and it was, nonetheless, his astoundingly simple and sometimes even funny style that frequently twisted rumours into a crystalline and non-aggressive irony. Many times his family and I have thought that the difference in character between Julio and Germán was similar to that between John Maynard and Germán. Keynes was the opposite of the man from Alicante. Keynes had it all, even luck. He was politically skilful in the internal politics of the astute British Treasury technocrats; seductive, ambivalent, cunning, clever, shrewd, snobby, elegant, a clever publicist of his own publicity, a great writer, and so on.

Julio wrote several literary works; ‘Infantilia’ was the most popular, precisely because it was the least objective of them all. They are memories painted with the watercolours of childhood fears in the setting of the family home, which is also described. ‘Infantilia’ was published in 1928, the year his father died, and dedicated to the person who may have known him best: his brother Germán. The book’s subtitle is ‘Emotions from Childhood’. You will understand why it seems important to me.

Julio Bernácer died in a foolish event during the Spanish Civil War. It was not an act of war that caused his death. Apparently the bus on which he was travelling was stopped by militia members and all occupants were shot.

Germán Bernácer, lecturer at

the School of Trade in Madrid.

Germán, as a scientist, was a stray sheep in the compact flock of scientific disciplines. First of all, he was an accountant who studied accounting mechanics and who slipped through the fields of Physics to escape through the window of the Food Industry. Without ceasing to be a physicist and professor of physics all his life, he was an economic scientist by vocation and this was how he was known. Fate or the inexplicable game of life wanted a Renaissance man to be born by chance in 1883.

However, furthermore, he was an untamed sheep that left the boundaries of classical and neoclassical economics. Of course, another sheep was doing the same in England. Keynes was a natural child of his time and of his profession. He was cradled by classical economists and hidden vice remained in his thoughts and doctrines. And they were awoken by the madness of stock market speculation and the roar of monetary inflationary and deflationary variations. Thus he ceased being classical. If some tried to let him sleep, others tried to awaken him. And thus Keynes created Keynes.

What I mean is that Keynes was a child of his time and his environment. But Bernácer was so unorthodox – although he didn’t know it– that he was nothing more than the biological child of his parents and nothing else. We do not know whose child he was in his economic scientific education. There were no resources for studying in the beautiful and provincial city of Alicante. There is no comparison with Cambridge. Spain was not home to the Smith’s or the Ricardo’s, Marshall did not walk its streets; his father was not John Neville, but rather a humble shopkeeper. His work was not in the activity of high finance or on the stock market or in the esoteric meetings of international economic organisations. He was also not a trader or an agitated speculator awoken from an impossible slumber by the death of the economic manuals that circulated during that period. Nor was Bernácer awoken from his slumber by the colossal uproar of the great crisis of 1929. Bernácer woke himself up with the marvellous stimulus of his own intelligence.

Man is the child of his environment, but he was not. However, this biography attempts to study Bernácer’s environment and the influence it had on him. Let’s continue with his childhood and adolescence. Alicante was not, like today, a city that lived from tourism; it lived from its commercial activity, maritime and fishing activities. Small, beautiful, it was surrounded by chunks of colourful landscapes: the blue blanket of the Mediterranean Sea, and a small mountain range surrounded by pine trees. Its climate was mild in winter and in summer and its streets were filled with an assortment of small family shops (one of which belonged to his father); a city of lively plazas with passing carts filled with goods, of wholesale fabric shops, of cafes where people talked about politics, bullfights or business, where they gossiped. They spoke of their simple lives and were pleased about everything from Alicante. The port received products from other parts of the world and Spain’s products were sent to other parts of the world. Everything travelled on uncharted routes, on the infinite destinations of the sea. The ships, untiring and slow, arrived and left bringing and taking things, ideas, and thoughts. Alicante by day was dazzled by a peaceful and powerful light with its blinding fires of creation that would be brazenly painted by Sorolla and, judiciously, by Varela. The light never rested, not even at night, a time when the giant oil lamp of the Levantine moon illuminated everything, as it always illuminated those that arrived there: Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Moors and the last privateers related to the Tower of Babel of tourism.

In the surrounding area, Alicante was decorated with a beautiful landscape filled with vegetation and serene, harmonious and luminous mountains. The creator forgot to turn the light off in Alicante and, day and night, light soaked into the skin and bones of the city, unlike in England. This light has marked the soul of its inhabitants, of its writers like Miró, of its musicians like Oscar Esplá and of its physicists and economists like Bernácer.

As was said earlier, Bernácer was born on Princesa Street and from the time he was little he lived with his cousin Tormo Bernácer. The inverse relationship of the surname Bernácer Tormo and Tormo Bernácer is explained by a marriage that joined the two cousins. Among the cousins, Manuel Tormo was Julio’s and German’s best friend. The common language was Valencian and Spanish in a family surrounded by the ethnicity and culture of the city of Turia. Germán always kept his tendency to speak in the language of his parents (and I had the good fortune that one of my articles on Bernácer was fully translated into Valencian).

The two families shared a flat at number 6 San Bernando Street, which reached up to Princesa Street (Altamira nowadays). On Princesa Street there was a lane that connected the home to the family business. The family business was a grocer’s called ‘La Tienda del Gat’, which, like all grocers in the town, was a family business, a small bazaar where you could buy a little bit of everything on your way home. The business sold rice, nuts, spices, toys, needles, thread, starch, soap, candles, ribbons, groceries…; in short, it was a small piece, a microcosm of gross national product. This shop and his home must have been the macrocosm where Germán existed and Alicante must have been the rest, the microcosm, and his 20 odd years of existence in the capital, Madrid, a small and confused anecdote of his life.

There is a belief, said by I don’t know who, that geniuses are really not as intelligent as we think; they just ask different questions. Elementary questions about the most elementary things. One wonders about the shape of the thing that is being stepped on which, except for small reliefs, is normally flat. This was a question formulated by Aristarchus, of Thales of Miletus, until reaching another man that stubbornly tried to verify it, who was named Christopher Columbus. Another, more incredulous and more elementary, wondered why the moon doesn’t fall and why an apple does. Newton would take some time (1867) to build the foundations of universal gravitation. Galileo looked at –surely with his eyes facing upward and his mouth open– the oscillation of the lamp of Pisa. Young Bernácer speechlessly contemplated the oldest and most tenacious operation of humanity, looking amazedly at what did not astonish any man that we know of: what astounded Bernácer was the operation of buying and selling that happened on a daily basis at the small business. His gaze went from the hand of the buyer to the hand of the seller. Behind his father there was something desired by the buyer –goods, threads, food, soap, etc.– and in the hands of one and then the other, there was a fleeting moment, an eternal moment, because it lasted nearly throughout all of history; something was exchanged: money. Their hands didn’t touch –thought Bernácer– they were joined by money. In reality, what both of them really wanted was money. There was a difference between the goods sold and money. From time to time, the person buying wanted a portion of what he was buying, and his father, the seller, did not want what he was selling; to some extent it was excess. Why, then, was it excess? Well, as a pretext to buy money. His father bought money with goods, and whoever bought goods supplied money to acquire them. Subsequently, he would repeat this many times in his economic manuals, in his research. ‘Whoever demands goods is really supplying money and whoever demands money is really supplying goods’. As to the rest, what he would say about the Englishman and those of his cultural ethnicity, including Spaniards who followed English economic thought –this idea about the supply and demand of money is not nonsense, but rather a meaningless statement. To say that money is demanded without knowing what is offered in exchange and to say that money is offered (monetary supply) without knowing what is demanded is an assertion that totally defies logic. It is not for literary embellishment that this work insists upon the environment surrounding Bernácer; it shaped the first concern of his life. In reality, everyone demanded money, although everyone used different means to get it. His father accumulated goods. The husband of the women buying sold his labour. Young Germán probably asked himself why money was not dispensed with; and he himself replied that it was because of how uncomfortable an exchange would be without it. In the same way that the alphabet brought over thousands of years ago by the Phoenicians favoured the exchange of words and ideas as well as communication in general, money, also invented by them, favoured trade and with it, production, and with production, the division of labour, as Adam Smith would put it. And the Phoenicians, the Greeks, the Romans, the Arabs, the Moors, the pirates, the kings, and even domestic thieves all did the same: they supplied money in exchange for goods, and they supplied goods in exchange for money. Alicante and especially the Levantine coastline have forever witnessed the trade carried out continually in the grand wet marketplace of the Mediterranean.

But when Bernácer was young and went to the port, he already found himself, along with his brother, astonished at the fact that the currency of Spain was one, and there was another currency, foreign currency, which was different, and that this complication was connected to the ships that were lost on the horizon. In addition, all of this was joined with a serious problem in the young boy’s mind, which he endeavoured to resolve. A special coin or some coins were made up of gold or silver. This was correct and properly understood; if the currency represented a value, it was logical that the coin itself had a value, and nothing could be better than if the coin were made of a valuable metal. Julio wondered if life were not a ship that gets lost in the sea of life. The brothers were different.

But he was also interested in payments made with paper. And paper had practically no value, like the paper that his father used to wrap up goods. Where was the secret? Once again he asked himself about the most elementary matter. He soon knew that the paper represented a sort of promissory note or acknowledgement of debt that banks held against its owner for a quantity of metal that the latter had left at the bank. If it were a credit instrument or an acknowledgement of debt, it would have a value, and as a value it would be exchanged for another value, which was a good. And if the unstoppable machine of trade and technology, the work necessary to produce it, demanded more money, there would be no problem if paper was created freely. This would not only be an economic sin, but also heterodoxy. And so what if there were no gold to back the paper? International trade carried out by these ships that he saw required a prior trade. This was unheard of! In the same way that salt cod was bought and sold, pesetas were bought and sold against sterling pounds and sterling pounds were bought and sold against pesetas, all of which was done to then trade Spanish wine for English cloth. Behind the English pound and the peseta there needed to be gold that preserved the pound and the peseta. And why did this golden backing exist? For no reason at all, to make trade more difficult. The true backing of the currency, or currency equilibrium, is not gold or silver, but rather production or goods. There was something more; the currency itself activated the creation of wealth. On the other side of the sea, in England, in 1913, young Keynes published a discourse on the functioning of the gold standard (Indian Currency and Finance). Keynes was 30.

Julio, Germán and their cousin Manuel would go up to the roof of their house during the day where the clothes were hanging to dry and they could see the mountains in the distance faded by so much light: Cape Huertas and the Dome of the Collegiate Church and of Saint Mary. During the star-filled nights, Julio and Germán would name the different constellations. Perhaps in the same way as Phoenician sailors in times past looked at them to reach Spain. And adolescent Germán was probably inclined to think that the Phoenicians, the Canaanites, who brought so many things from so many places, did not also bring the demon of other Chaldean gods like the golden calf that perpetuated, through the gold standard, its malevolent influence.

He practically never changed tastes. What he liked as a child, he kept when he was old and loved even more. And what he loved was a quiet, family-oriented life frequently altered by the greater calm of nature, of the country, of the marvellous Aitana mountain range and of the sea in the company of his inseparable friends Oscar Esplá, Gabriel Miró and Varela. Germán penetrated deeply into nature, with the nature of his land, the nature of Alicante. At night he liked to examine the skies. During the day he liked to swim and he swam so deep into the sea that he was lost from sight and his family members worried about him.

His finances, which were not abundant, were stretched to make small, humble, country houses that allowed him to be closer to nature. He had a house built very close to Juan Vidal’s house in the land of Aitana, which is today naked and degraded by housing developments. According to family members, in that time, without a car and without current healthcare resources, the trip to Colot was an adventure. In San Juan, in front of the sea that was sometimes calmly and sometimes furiously whipped by the wind, he built a small home. The Germán from Alicante and the Germán that lived in Madrid can always be found alternating reading, meditation, a peaceful life with walks in the mountain and swimming. Miró, Esplá, Varela and Bernácer were what are now known as environmental enthusiasts. This piece of parochialism was always acclaimed by the three friends and was faithfully reflected in their works: Oscar Esplá in his music, Miró in his books, where he talked about customs and scenery, and Varela doing what was impossible – painting the eternal flash of the Alicante light that was never extinguished.

Childhood emotions, intuitions, fears and its endless curiosity gave way to adolescence, and along with it, the overwhelming reality that enters your home like a corpulent tenant. This neighbour was called economic reality. The shop went from bad to worse and I believe it had to shut down. Bernácer was forced to help his family out financially by giving classes in the morning, reserving nights to study by the light of an oil lamp. For many years, the oil lamp would be German’s silent companion in an Alicante that had no electric lights at the beginning of the century.

26.3. Professional life in Alicante

Germán began practical studies that allowed him to earn a living in a city of merchants. He studied to be a technical accountant, a branch of accounting that precisely tracks reality with as much monotony as accuracy. The mathematics involved in such accounting only amounted to adding and subtracting, but it would serve to keep him rooted in crude and frugal reality and not dreaming about things other than observable and observed reality. It would also help him to defend his own criteria with respect to general macroeconomic accounting. He began his studies when he was 14, the same year in which his Business Studies School was elevated to the rank of higher studies by Royal Decree. Although ‘higher’ may seem to allude to grandeur, it was not a university, but rather a simple trade school.

In the 18th century, the city of Alicante began to dispute with Valencia for an autonomous consulate, which was obtained in 1875. Thus, the Council of Commerce, the Consulate and, obviously, the Business Studies School were formed.

The business studies there had two levels: elementary or expert (certified accountants) and higher or professorship (business professors).

The following disciplines were taught: Arithmetic and Business Calculus; Accounting and Bookkeeping; Commercial Law, Customs and Trade Practices; Political Economy and Modern Languages. Logically, since it was a school, it did not require a high level or much depth in studies. It was also normal that a school that was not the Faculty of Economic Sciences (created approximately 45 years later) in a small city did not have a well-stocked library. Two things, however, should be stressed. The first is that the elementary political economics studies rapidly attracted Bernácer attention. The other is that language studies also caught his eye, and the languages that drew his attention were French and English. As for the other disciplines, business calculus, arithmetic and, even less so, accounting should never be looked at with disdain; they are true gymnasiums where the ever-so-necessary musculature of logic is exercised.

The second group or level was comprised of the following classes: History of Commerce and Industry, Geography and History and Recognition of Commercial Products. Bernácer would later come to teach the latter subject and not the field about which he knew the most: Political Economics.

German’s superb ability of abstraction rose above the small jungle of homogenous disciplines, and it was this ability that resulted in his elemental and compact logic to understand what was happening in the uproar and clamour of street trading, fish auctions, banks, ships and agriculture. Thus, his impeccably solid scientific style was simple to the point that it irritated economic scientists that played and play with the mystery, the magic and the hypocrisy of useless technicalities. His childhood curiosities undoubtedly increased at the school and there, and in the street, especially in the street, and in the mysterious solitude of the oil lamp the answers became weaker. The Alicante Business Studies School seems to have had all of the resources necessary to develop his activity. The City Council and the Provincial Government and the support of other institutions helped the school to mature and develop. It is necessary to understand that in a small city, business professor studies, which were practical, were tightly intertwined and connected to the economic reality of the provincial city. Job offers were quickly filled by capable students. The Business Studies School was a natural part of the business life of the Levantine city. According to Oliver Narvona, who has meticulously studied the environment and the history of end-of-the-century Alicante, Gironés de Puerto, Professor of Economic Geography, directed the school. The Registrar was Campos Vasallo and the faculty was composed of: Campos Barrera, of the Development of Consumption and Industry and Complements of Geography; Soler López, of Natural History and Recognition of Industrial Products; Enrich, of Accounting and Bookkeeping and Business Operations Practice; Domínguez Navarro, of Comparative Merchant Law; Leveroni Morales, of Italian; Olivares Gil, of French; Fornier Padilla, of Arithmetic, Business Calculus and Calligraphy. The assistants were: Campos Vassallo, Santonja Gil and Sellés Gonzálvez.

Germán Bernácer, Oscar Esplà and

Agustín Irizar.

From these disciplines, it is necessary to take a closer look at ‘Recognition of Commercial Products’ and professor Soler López, because they would have special meaning in this future scientist’s mind. This subject, which would later be called ‘Industrial Technology’ and later, most likely, ‘Testing and Evaluation of Commercial Products’, clearly revolved around ‘Physics and Chemistry’. The accountant Bernácer, although as far as I know he was never an accountant, was in reality a professor of Physics and Chemistry, as subjects that shaped his shapeable and alert mind. As a researcher, he was an economist. Economic reality and economic theory are not physical facts and this, above all, was something that Germán knew. But there is an aseptic and pure rigour in physics that lifts it above other sciences. Observation, the incorporation of this observation in theory, the theory of observation and the mathematics linking logical events, all make physics and the physicist an almost perfect scientific fit. As for the rest, concepts like velocity, acceleration, elevations and flows, elasticity, etc. are similar to economic concepts: the speed of circulation of money, etc. Germán also knew that many things were different in economics than in physics. The most important thing is that wealth and money, unlike matter, are created and destroyed. And he also knew that alchemy was not such a mysterious matter, that it was a matter of chemistry and physics and that economics had something similar to alchemy. It was pure alchemy. And he wanted to one day understand this matter, this economic alchemy. What was the chemical process that Germán wanted to comprehend? What was the philosopher’s stone? It was simply how wealth was created. How wealth was created in factories, at workshops, in fisherman’s nets, in orchards. The issue was contemplated as follows: the alchemy to be explained was the transformation of money into real wealth, i.e. assets. Bernácer later found the answer.

Soler López, professor of ‘Recognition of Commercial Products’, greatly influenced Bernácer. Bernácer was the teacher’s aide in López’s official chair where he gave classes and conducted practices and experiments. Germán was appointed teacher’s aide according to his personal record dated 31 October 1901, which was the year he received his degree. According to a subsequent certificate ‘he was appointed by the Honourable Chancellor of the University of Valencia and at the proposal of the Faculty of Professors of the Business Studies School as a temporary free Auxiliary Professor’. The aforementioned certificate says that on 18 November 1902, by agreement of the faculty, he was appointed: ‘Personal assistant of the professor of Physics and Chemistry, Natural History, knowledge and application (illegible) of business and recognition of commercial products…’ 159

Physics labs had to be conducted at the municipal laboratory located at number 3 Cádiz Street, which had been set up by chemist Soler Sánchez. Insistence and hard work made it possible to improve the school laboratory between 1905 and 1910. The chemistry laboratory was created at a slower pace until 1903, when splendid instruments arrived from France.

From the beginning of his time spent as an assistant professor, Bernácer carried out physics experiments, which fascinated him. He liked the seriousness of the science called physics, which never failed and could be represented mathematically on paper like a second lab. Strangely and inevitably, the two unrelated trainings would complement one another in Bernácer: accounting and physics. Accounting is a way or recording what exists and nothing but what exists, and physics experiments with facts that also exist. And these two sciences (physics overwhelmingly exceeds accounting as a science) shaped Bernácer’s scientific personality, where there was no room for useless metaphysics or fallacy or unnecessary learning.

But Germán was truly an economist, although his degree was not in economics, and as an economist he wanted to understand the economic events around him. He wanted to understand the explanation of misery; how misery was created, the same way that the gold block of wealth originated from the philosopher’s stone. Physicist-accountant Germán wanted to understand the other transmutation and how it went the other way: How could heavy shiny gold be turned into ash? Or laughter into tears? He wondered why physics and its new discoveries, minted in the engraved glory of technological innovations, told him that wealth was easy to create and that as humanity advanced, poverty would be banished. And since it wasn’t banished, there was an asynchrony between the capacity to generate wealth, the same wealth and poverty. The answer does not have to do with the unequal distribution of wealth, as the late Marx would explain it. There would be a much more profound internal explanation.

On 18 June 1901, he earned his degree to become a certified accountant with a grade of outstanding. This was the same year that he enrolled at the school. He was 18 at the time.

For nine years Bernácer had been trying to heal his spiritual scar created by the death of his only sister Isidorita (1897+), who had been loved by all. This was an event that wounded the entire family. His mother was deeply affected and never really recovered.

Since 1899, Spain had been living horrible years that affected its dignity, its politics and its economy. The empire was drawing to a close and the glories of the crown were crashing down. Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines left to never come back. The Caroline and Mariana Islands were sold to the highest bidder. And all of this was combined with the new yet faltering reign of Alfonso XIII; the labour unrest of 1901 and the problems with Morocco the same year that were undermining an already-outdated economy. Like other ports, Alicante received the influx of the fall of the national economy; and like other families, the Bernácer family saw a decline in income, production and trade at their shop. They moved to Bazán Street. Bernácer’s mother, whose health had been poor since the death of her daughter, got worse. Bernácer, as the eldest brother, was called upon to assume responsibility, to rescue his family from the precarious situation they were in. Thus, he began giving private classes to students at the school. In the darkness of his personal and family situation, there was a glimmer of light via a call to take official exams to become a professor of Industrial Technology, which was also called Study of Principal National Industries. There was an opening in Alicante itself, and it would be given to the person that earned the highest mark.

The diminutive study of Germán Bernácer in the

seafront house of the San Juan Beach in Alicante.

The exams were held in April and May 1905. Bernácer, at 22, was named tenured professor of ‘Industrial Technology’ at the Business Studies School, per Royal Decree of 19 May, with a salary of 3000 pesetas, ordering the undersecretary of the Ministry of Public Education and Fine Arts, the Count of Albay, to give him possession of his post. His long-time friends Miró, Esplá, Castillo, Irles, etc. were ecstatic about the news and according to Oliver ‘they went in droves to the Encina Station to accompany him from there to Alicante, joyfully congratulating him for the victory’. A few days later, Bernácer officially took over his position as professor in the presence of School Director Manuel Gironés, with Hipólito Domínguez acting as registrar. He turned 22 the following month.

He was already a part of the faculty of professors, further developing, now as a professor, his relationship with his friend and teacher Soler López, who would later be the school director and to whom Germán owed so much. His salary allowed him to more easily attend to the needs of his family. The efforts put forth for the exam made it possible to see another of German’s character traits: his enormous sense of responsibility, which he showed first as an older brother and later as a father.

He was from Alicante, in his character, his culture, his feelings and his passion. That explains why he stayed in Alicante, working as a professor, for 25 years, five months and 27 days, according to his personal record (and the biographical and precise accounting of Oliver). His primary co-worker was, inevitably and happily, Martínez Soler, with whom he worked on laboratory tasks as well as on the lab’s expansion. Another interesting figure was Vicente Martínez Pina, degree-holder in Political Economy and Comparative Commercial Law, because Martínez Pina’s education on economic theory made it possible for him to closely look at German’s work and evaluate it according to his knowledge of economic doctrines. The conversations the two held must have been interesting; it is a shame that they didn’t live in different cities, because the letters they would have written one another, if kept, would have given valuable information about Bernácer’s thoughts regarding this subject. Another faculty member was his restless and cheerful brother Julio, who was a Professor of Modern Languages from 1912 and was associated with the School’s Department of Sciences. His brother was fluent in English, French, Italian and German, as was Germán. Julio prepared to take official exams in Business Accounting and gave classes at the Iborra Academy and at the French School. Afterwards, he worked as an administrative assistant at Tabacalera S.A. in Alicante and later in Madrid, after 1932, just a few years before his absurd death.

Bernácer was fully dedicated to his work as a teacher and to preparing laboratory experiments. He even managed to prepare interesting textbooks for the Business Studies School between 1906 and 1936. There are references to a physical methodology book around the year 1932.

Such information may lead to the belief that Bernácer as the hidden researcher was always in the shadow, in total anonymity. This is not true. He held positions of a certain level of importance, but he never tried to arrogantly flaunt this fact. In 1906-1907, when he had been working as a professor for one year, the school registrar, Hipólito Domínguez Navarro, resigned and it was necessary to fill the position. A vote was held and Germán Bernácer was chosen. He began occupying the Registrar’s Office on 28 January 1907. He took over the position on 5 February and left it on 22 August 1909. He was once again appointed registrar per Royal Decree of 21 April, and he resigned on 31 December 1916.

His education at the school opened the windows of his understanding to discover the enigmas of his childhood and his adolescence: probably the enigma of buying and selling. Accounting and commercial law taught him what he already knew: businesses asked for loans to fund their activities. The economy was a marketplace in which voices wanting to buy were crossed with voices asking for loans. Business owners who contributed money from their pockets were also lenders of their own businesses. It was clear that companies, as legal entities, owed money to their shareholders, as individuals. In both situations, debt-based relationships were formed for those who owed and credit-based relationships were formed for those who lent, and all of this was formally and legally documented by means of beautiful papers decorated with the trumpery of strict protocol: they were shares, securities, bonds, certificates, vouchers, etc. Germán soon advanced as a silent sailor through the hidden monetary circulation of the economic system. It will be clear later that this is not just a blithe sentence. One loans what is not consumed; savings are lent. Thus, the savings of some –capitalists– fund investments of others, the producers, entrepreneurs and businesses. In theory, savings should be the same as investment. And what is investment? For Bernácer, it was the use of savings to fund the acquisition or formation of capital goods.

Germán Bernácer seated third from the right. It is very likely the group at Research Services of the Bank of Spain.

At a later time, in the physics lab, physicist-accountant Germán realised two things: that these papers called shares, securities, bonds, etc. that provide a record of a simultaneous credit-debit relationship are the ships that carry savings to investment, in the same way that when he was a child looking out from the balcony of his home he saw the ships carry goods abroad.

Nonetheless, he was astonished when he understood what the man of the street, the great business owner, the grand banker and the humble innkeeper had known for some time: there is a market in which these securities – these stocks called financial assets – were bought and sold. At the stock exchange, in a loud voice according to internal rules, securities were sold and bought; just as in his parents´ shop, where the fishermen, knife sharpeners, greengrocers, barbers, ice-cream vendors, etc. cried out, announcing their goods. The value of these securities was bought, or what may be better understood, buyers basically bought the capacity of these securities to generate (non-production) income. These types of assets were combined with real assets such as land, buildings, plots, the mere possession of which entailed the ability to obtain income. It was a lesson that came from the past and reached Bernácer’s eyes with uncommon energy. The lessons learnt from commercial law and accounting about matters such as liabilities, equity, non-depreciable fixed assets, stock portfolios and so on, were ideas seen differently by whoever was different. The shouting of street vendors and the scandal of white collar salesmen in the stock exchange and the continuous disorder of the souks of the ordinary and of the financial market were interpreted and translated like a magical order that was only understood by Bernácer.

This is the work and findings of scientists: to find a logical order, the law that governs movement in an entanglement of apparent disorder. He noticed that a common activity coordinated this ruckus: everyone demanded money and in the middle, some supplied it and others asked for it; it was supplied by those who bought goods and it was demanded by those supplying these goods, whether these goods were tomatoes or soaps or shares in tobacco companies or chemical industry bonds. But, there was something else. There were traders that didn’t shout, but with the most absolute discretion and outfitted in dark suits –scribes and distinguished gentlemen– carried out an ancient task in the world, especially in the Mediterranean. They were bankers. They remained silent because their goods, money, were in such high demand that they advertised themselves like an organic claim –hunger, thirst– in the minds of men. In addition, this money was not theirs, it was others´. Their business consisted of negotiating this third-party money with others, charging interest. And here is the word, interest, the concept, the poisonous reality that preoccupied him scientifically throughout his life and that as a secret curse spilled into earthly paradise, tormenting mankind… interest. The price of things being a quantity of money for a unit of goods also worked for money; money also had a price, and this price was interest. Without a doubt, a remarkable thing.

In the small city of Alicante, like in most Spanish cities, in the towns and large metropolises, a day-to-day reality full of bitterness, of terrible family tragedies, closed in upon men, and it was seen as the most natural thing in the world. Bernácer contemplated the existence of pawnbrokers, the evil aggression of usury that cleaned away wealth with a sharp scythe. The problem was not the usurer, but rather the interest of money. For this reason and for others, a moral concern hounded Bernácer in his scientific projection, as capital hounded Marx. The interest of capital, of money, had to have come from a perverse root and not from wealth. It did not come from production, as was believed by producers. Production, through the ordinary market (as it was usually called by Germán), created wealth and not misery. Moreover, interest was the door that closed the passing of the flow of money to the productive garden; then, interest is located outside production, out there, very far from earthly paradise. In the city of Alicante, when the empire fell with the tragedy of Cuba, the Philippines, etc., as in most of the emerging Spanish nation when it was created in the times of Philip II, the usury loan was an everyday reality, and it is not certain whether his family suffered this reality. In an economic collapse, when large and small businesses fall, like his parents´ business fell, the hyenas of the system leave their dens to satisfy others´ need for money and then, when the money is not returned, they keep everything. There was a psychological, personal and moral environment in Bernácer’s surroundings that made him look back to analyse this evil creature called interest. He couldn’t bear to contemplate how someone could accumulate wealth without working, i.e. with the monetarily (not socially) productive parasitism of interest. These issues were contemplated by the certified accountant with knowledge of political economics, accounting and commercial law fresh in his mind while he carried out physics experiments and while he strolled in the bustling city of Alicante. Around him he saw that there were people who lived to work and those who worked to live, and there were others who wanted to work but couldn’t find work in the market, and there was a parasitic cast that lived without working thanks to comfortable non-production income. Financiers (those that lived from investment income) were not workers. They lived from the work of others, because if they consumed goods that they had not produced, it meant that they had been appropriated from others. The mere possession of financial assets, of homes, of fertile lands, allowed them to obtain convenient, free and secure income, due to a peculiar confirmation of the economic system. And since these assets were acquired with savings and had a value, the percentage yield of the savings invested financially was the result of buying this value with the income that it provided. This meant that if an asset was acquired for 1000 pesetas and yielded 100, its percentage yield was 10%. This is where interest comes from, not from anywhere else! Outside of production!

It was necessary to show that these financial assets were not social and productive wealth, contrary to the teachings of economic textbooks and, later, Keynes, his followers and the entire legion of untiring macroeconomists. The issue was quite simple. After taking savings to investment, after forming equity, after financing the productive system, financial assets, securities, bonds, etc. do not die like bees after stinging. And it would be logical that these papers –simple acknowledgements of debt and a promised yield– remain recorded in a book and nothing else. But what happened is that these papers were bought and sold, and to do so, it was necessary to have much more savings than was needed in the beginning. The same thing happened to quiet and bored landowners that dozed in the colonial cafes of Alicante and to landowners who continually bought and sold. And, for such activities, society as a whole required huge quantities of savings, well above the savings needed for the original financing and service provided.

From the crazed chaos of blood, Servet knew how to notice order, and others were able to channel this order and discover not the flow of blood, but two flows: one in the veins and the other in the arteries. Other scientists discovered the mystery of air and blood: one flow gathers oxygen and carries it to the cells where it is burned, taking the carbon dioxide that is expelled by the lungs, resulting in another flow. Bernácer, in the tremendous chaos of the ordinary market, of the quiet and underground banking where there was a confusion of grocers, bazaars, vegetable sellers, fishmongers, gunsmiths, hairdressers, stockbrokers, speculators, financiers, functionaries… was able to understand the order that, although perverse, was indeed order. One market was the ordinary market, where true goods were produced, where production compensation known as production income (wages, salaries, etc.) was produced and sold. This is where wealth and income was generated and where the wonderful alchemy of the biblical and sacred transmutation of money into wealth occurred. The other market was where signs of wealth or artificial wealth were bought and sold, where financial assets were bought and sold. Both markets, the ordinary and the financial market, needed the common blood plasma of money. Yet, financial assets were not wealth, but rather an illusion of wealth, an illusion of the wealth that had been generated. It would be like if next to the shops, fruit shops, etc. there were mortuaries that did not shout to sell their goods, but sold them nonetheless.

The physicist realised the obvious, which is that the gift of being in two places at the same time cannot be found in the physical world of mortals; only in mystery novels; and in the economy, there were no possible secrets. If savings were in the ordinary market, they could not be in the financial market and vice versa; this meant that the financial market stole money from the ordinary market. Of course there are flows of spending and buying from the ordinary market to the financial market, which give rise to different yields of capital goods, and there are inverse flows, which make income go from the financial market to the ordinary market. This reshuffling of net flows is explained by the theory of economic cycles.

According to statements made by Bernácer, in December 1905 he had an idea made up of discovering monetary circulation in the mechanism of the circulation of money, more exactly through the organs of the economic system, specifically three main arteries: consumer spending, spending on capital (investment) and disposable funds; the latter would be spent in the financial market and would not stop being disposable funds. This idea was the secret code of German’s entire work. Maybe it was luck, or maybe not (luck is sought). The truth is, it was a colossal idea. Bernácer stated ‘…Regretting, not least on my part, that my work will not find in its day an environment better suited for its dissemination, because that would have given this orientation of monetary theory, which I think successful, the help of the best brains, which would impress it with quicker momentum. I think I can prove, even without the advantage that a competent critic would have provided me, which I have been lacking, that the poor seed that germinated one day in December 1905 has now reached momentum in its results, that it may go hand in hand with those obtained by other more or less academic economists, who have also stopped thinking in terms of perfect equilibrium…’ (concerning Robertson’s quote). These words were expressed verbatim in his book The Functional Doctrine of Money (1945) when Bernácer was 62 years old.

He looked back and found himself in the centre of an infinite market, astounded by the shouting and disorder, and suddenly, on his feet, he was astonished, since he had found the key that explained it all, the theory of money and of circulation. This young man in the infinite and eternal souk of the market immediately found a way out. He was 22 at the time!

It is common for good scientists to arrive at the city of the truth without following the arduous and prolific path of demonstration. This happened to Germán, who, aware of his achievement and of the need to pave the intermediary path, devoted the rest of his life to doing it. He would finish this feat 50 years later, with a vast amount of work along the way, in his book A Free Market Economy without Crisis or Unemployment. The young astonished man of 22 would agree with the wise man of 72. The obsessive observation of economic reality and the constant reading of related works, which in fact were scarce, and the repetitive and almost fanatical note taking, matured into a great book that would be handed over to the printing press in 1915 and would be published the following year. This book had sprouted in 1905 and it received moral strength in the wake of a trip around Europe.

He had the opportunity to take advantage of a scholarship in Belgium, Germany and Italy for eight months. There is no doubt that eight months is little time to study. If, in addition, it is coupled with the difficulties of the spoken language (not the written language, which Bernácer knew), moving from one county to another is difficult. His personal record states that ‘as per Decree dated 25 September 1911, he is granted a scholarship lasting eight months in order to study Technical Sciences in Belgium, Germany and Italy’. The scholarship lasted from 1 October 1911 to 31 May 1912. Certain experiences marked the will of the researcher, and this was one that stirred Bernácer. As stated before, this was little time to learn technical sciences, but a man whose mind was restless and fed by the rich minerals of economic theory knew how to draw conclusions from this interesting trip. The truth is, more than conclusions, he ended up with concerns and questions. He knew about the circulation of money and began to understand the origin of interest, and this origin was found in the perpetual income provided by land to its owner. The ordinary market of Europe, the production market, was lit by a number of flares coming from human minds. These flares were the technical advances that brought together the economic idea of classical economists and made the productive workshops of mankind much more productive. The emergence of synthetic rubber, the first submarine, colour photographs, the use of large machinery that intensively multiplied capital and, more slowly, the appearance of the theory of relativity, which, as a physicist, captured his attention, let him know that mankind had found the path that went from the valley of tears of misery to earthly paradise. The horn of plenty had been found, and he was worried that mankind was getting poorer without knowing why. The creation of greater wealth was starting to be distributed to the horde of workers, and jobs were wanted by those who didn’t have them. Great political and economic units suffered internal and external tensions during those times. Political agitators promised paradise on earth (where else?). Emerging wealth allowed everyone to dream about good things and not about the horrors that were soon to be, the horrors of the First World War. The conclusion drawn from this trip was the understanding of the asynchrony between the capacity to generate wealth and the misery on the other side. Production capacity is capital goods funded by savings, and these savings are captured. This is the cunning of interest and what leads to the decapitalisation of businesses.

He finished writing Society and Happiness in 1915 and it was published in 1916. The title, which was very misleading, diverted the attention of researchers of Bernacerian works, and they did not give it any importance. I have inventoried and closely examined Bernácer’s monetary construction beginning with ‘The Theory of Disposable Funds’ from 1922, and after that time I worked with subsequent publications. Nonetheless, the book from 1915-1916 was not forgotten, because I didn’t even bother to flip through it, due to a meaningless alleged common sense that believed that a book with this title would discuss utopianism, literary fantasies of a learning economist between 32 and 33 years old who must therefore not have a solid background. The title, I stress, Society and Happiness was followed by ‘A Test of Social Mechanics’, both of which I instinctively rejected for the same reasons. A lagging physicist from the past century, as so many other learning sociologists, utopian socialists, steeped in the modern dress of neopositivism, undoubtedly wanted to construct, as Comté, a sort of social engineering.

Common sense and instinct failed. The subsequent reading –pure effort of scientific decency of having to read it out of obligation– let me be doubly astonished by this work, Society and Happiness. It was an abstract and profound work that sowed the harvest that would be collected years later. An interpretation of David Ricardo’s income appears in the first pages, the origin of interest, the circuit and monetary equilibrium and, also, the balance between real return on capital and money, matters that are subsequently discovered. It is a book on macroeconomics when well read, a book on morality when properly understood. It is, moreover, a work that, being the first, is abstract, complete, comprehensive, unlike the rest of his books, which were more enjoyable and more specialised. The creative strength of the young man of 33, a physicist and certified accountant, annihilates those scientific concerns that had bothered him for years. It is a robust tree that grew from his happy intuition in December 1905, watered by immutable springs of hours of reflection and by his brief but fruitful trip around Europe.

The book was published in Madrid at the Modern Library of Philosophy and Social Sciences by Francisco Beltrán. According to the book, a previous work had already been written by the untiring physicist that was entitled Food Industries, which was published in Alicante 10 years earlier, in 1906, when Germán was only 23 years old and was just beginning work as a professor.

His mother, who he respected and worshipped, died in 1917. It was the second blow after the premature death of his only sister. Two years later, in 1919, and as a result of much thinking, that great tree of Society and Happiness began to bear fruit. He published his first economic article in the journal Revista Nacional de Economía. The article was entitled ‘Currency and Social Issues’, and in 1921 it was followed by ‘Two Current Issues: Banking Law and Tariffs’ and ‘The Monetary Problem’. The plan was designed in his mind, but he lacked something that allowed him to connect economic operations and their impact on income: consumption, savings, capitalisation, decapitalisation, the genesis of disposable funds, all of which are made with money and, given that they are made with money right there, they should comprise the monetary market: the supply and demand of money. The plan was designed and published. It was the theory of disposable funds, the master key to the work of Bernácer. It was published in Revista de Economía and sent (most likely in French) to many economists around the world, including Robertson. It is not certain what happened to this work in the hands and understanding of Robertson, if Keynes read it or not; what is certain is that its echo took 16 or 17 years to be answered. Robertson brought attention to Bernácer and to his article in the journal Económica in the year 1940.

Germán began to enter cultural circles in Alicante. He joined the editorial committee of the magazine Literaria Local. He was later appointed secretary and subsequently vice-president of the Alicante Literary, Scientific and Artistic Cultural Centre. Alicante and its weather formed a peaceful space where he felt comfortable. He had time to work and to think. His life was calm and tranquil while taking care of his mother, elderly and ill, resentful since the death of her daughter Isidora until she died, and taking on the financial responsibilities of the family. Teaching and research used up his free time. He was a man of few friends; he only spent time with Miró, Esplá, Varela and a few others who, unlike other Spaniards whose national pastime was to spend time at cafes, preferred the solitude of the beaches and the secret noise of nature. He was 34 when his mother died. Bernácer was still single. For a shy and quiet man like him, it must have been a considerable problem to perform the ritual ceremony of the wedding party.

They were prolific and tragic years for Europe. Englishman Robertson was pondering his Money”, and the other Englishman, Keynes, published his Treatise on Monetary Reform in 1923, a work in which, like an angry Moses, he knocked down the gold standard, the guilty cause of the sin of unemployment, something that Bernácer already knew. Keynes was an advocate of paper money (that is, without metal backing) to finance economic activity, since equilibrium was required, not between currency and gold, which was absurd, but between currency and the wealth created, which was logical. This is what Germán Bernácer had clearly said in 1917 and throughout his life: that new currency should be created to finance working capital and that savings should finance fixed capital, since working capital, when clearly understood, is nothing other than the wealth created or national product. As Lucas Beltrán Flores 160 said (not the editor of Society…), the years from 1870 to 1930 were bountiful ones for economic science. After the contribution made by Wicksell, there was Hawtrey, Shumpeter, Hobson, Clark and a long and fruitful so on. Doctor Schacht in Germany managed to defeat the thousand-head serpent of frightening German inflation, creating the Reichsmark. This important economist and well-known German banker had read Bernácer’s works in Germany and when he was invited to Spain, he asked to meet him in person, at the surprise of his trip organisers, who didn’t know who Bernácer was.

26.4. His marriage and children

The circumstances of scientists’ personal lives surely condition their science. An unfortunate event –and a bad marriage is one– can destroy scientists much more effectively than someone finding an error in one of their math proofs. Bernácer was still single at that time, with marriage in the future. This marriage, which was a lucky and good decision, would chart a sunny and warm path through his scientific research. María Guardiola would not only be his lifelong companion and the mother of his children, she would be the glass house where Germán could hide away, unaffected by the perpetual drizzle of domestic problems.

The period of dating, of courtship, of asking for her hand, the complex and ceremonious ritual in those times is something that I will never know about, because I cannot imagine introverted Germán going through this emotional and social relationship without a great blush on his face. Nonetheless, I will hazard some assumptions.

José Guardiola Ortiz, Maria’s father, was a renowned and prestigious criminal lawyer and an indomitable Republican. He was a councillor as an independent radical-socialist in April 1931. He became Civil Governor of Valladolid and was appointed ambassador in Portugal. He had a strong character and always had a strong curiosity about intellectual matters. This is seen by his conferences and his broad education, which not only included intellectual subjects, but also encompassed the sensual culture of cuisine, which is one of the undeniable manifestations of a people’s civilisation. He was a great connoisseur of Alicante cuisine and also a good cook. His love of food can be appreciated in his book The Cuisine of Alicante and Wartime Dishes.

He was friends with a mutual friend of German’s, writer Gabriel Miró, who he admired and whose writing he loved. A second book was evidence of this esteem. In fact, Intimate Biography of Gabriel Miró, published in 1936, was kept by his daughter María and by Germán as a precious relic. This book, filled with rich and colourful fabrics, also had beautiful illustrations, some of which were done by the hand of another friend, Varela. One of Maria’s uncles, her father’s brother-in-law, was journalist Emilio Costa, who died after the Spanish Civil War in a concentration camp (Orleansville) near Orán. A group of friends, including Germán, collaborated with this director of Diario de Alicante newspaper.

Young Bernácer was at the home of his older, talkative and well-spoken friend José Guardiola. It is likely that through José’s brother-in-law and mutual friend Gabriel Miró, Bernácer got to know the Guardiola family and was introduced into the family environment of this cultured dynasty. Another site of intellectual debate was the Huerto de los Leones in San Vicente, which was a meeting place of the friends of José Guardiola, then President of the Cultural Centre, called by G. Miró: ‘La casa Hidalga y amiga’. According to Oliver, in addition to a fondness for conversation and reading, they were joined by a penchant for sunbathing and swimming (Germán even sunbathed in Madrid, when this trend had not yet caught on in society). They held long conversations at the ‘Belvedere’ chalet in Muchavista, which was in front of the sea.

The truth is that wherever Don José was, his daughter was generally there as well. And thus, the love and affection that would later unite the two in matrimony was born. I believe that the secret romance, so secret that the couple didn’t even know it, evolved through a loving and silent plan coordinated by Miró, his future father-in-law José Guardiola and other friends who, knowing Bernácer’s reserved and shy nature, wanted to complete the impossible mission of finding him a girlfriend. The plot, which was secret, since it was surely never spoken about but was understood in the invisible and spiritual language of friendship, did not lack difficulties, given that María was 20 and Germán was 42. A 22-year age difference! At a time when masculine sieges, calculated and managed by the bride in the outlines of baroque formalism, were titanic feats, I do not know how Bernácer managed to end up at the altar on 17 February 1926. I refuse to explain what I don’t know, which are the details of the courtship. It is enough to say that German’s shyness prevented him from following the insurmountable protocol of asking for her hand.

Germán not only married late, but he also arrived late for the wedding, as a result of his incurable shyness. On his wedding day, Germán was fulfilling his promise to listen to ‘La Pastora’ by Ernesto Halffter at Oscar Esplá’s home. The music was good, as well as very long. Time went by and as the wedding hour drew near, causing shy Bernácer impatience and nerves, he remained in his chair due to a combination of politeness, shyness and embarrassment. It was surely his friends who finally realised it was Germán’s wedding day and turned the music off, accompanying him to the church. At the church, an uneasy and happy José Guardiola waited nervously for his scatterbrained son-in-law, whose defects he already knew well. Who know how many times José looked at his watch.

There was a way of doing things among the young intellectuals of Alicante, who, to some extent, wanted to do things and ceremonies, but in a different way, without the baroque oppression of customs and manner. One of these things was the wedding, which was celebrated at the Collegiate Church in the small communion chapel, where María Guardiola Costa and Germán Bernácer Tormo got married in an intimate and informal wedding surrounded by close friends.

Four children were born from the marriage: Eda, Germán, Ramón and Ana María. One of the boys, Germán, inherited his father’s fondness for physics, and he earned his degree in this discipline. Ramón, or Rom as he was called by his father, earned his university degree in Economics and Exact Sciences and studied to be a Business Professor.

He was a responsible and selfless father who always knew how to provide his family with the financial security that makes a home peaceful. He was his children’s father and teacher. As a capable man or, better said, as an economic man, he never stopped being a government worker, whether as a professor or as a technician at the Bank of Spain. His psychology was somewhat that of a government worker who knows that his limited salary is as sure as it is unsubstantial. It was this security that gave him a certain peace-of-mind, and it was this limitation that always caused some anxiety, although not much, in caring for his family. It appears as though this was true when he retired late in life. The great economist did not know how to hold on to earnings; he lacked entrepreneurial spirit and the adventurous impetus natural in a businessman; he didn’t know how to deal with unexpected situations. He only knew how to bring his wages home and give them to his wife. He didn’t earn money with economics, nor did economics give him a special status. His wife María, or Maruja as he called her, handled the family finances and, to make matters work, she constantly struggled to make sure that Germán, the everyday Germán, carried money for his expenses. When she was careless, it was possible to find a lost Bernácer on the street or on the subway, frenetically looking in the depths of his pockets for a single coin. Not carrying money on him was one of his character traits, a revealing one at that. How different from John Maynard, for whom money was a part of his life and his entertainment! He handled cheques and foreign currencies with the skill of a swordsman. I can imagine him, happy and content, going to the bank to ask for loans in order to go to the stock exchange and buy and sell shares, surrounded by the excited shouts of brokers, winning, losing, returning loans, riding his toboggan up and down the peaks and valleys of the preferences of public liquidity in the City of London.

When Bernácer got married in 1926, he had just published the memorable article ‘The Economic Cycle’, which was the prolific child of the third part of Society and Happiness, a book that gave him his nickname (created by Gabriel Miró) Germanazo (or Big Germán). Afterwards, the book The Theory of Interest… and the article ‘The Theory of Disposable Funds’ were also spawned by Society… He understood the hidden route where monetary rivers flowed and the steel floodgates that held them in and the silver keys that, as capricious as they were, opened and closed income, and the desert of salt and saltpetre where savings disappeared and where humanity, the unemployed, income and wealth died of thirst, far from earthly paradise. He understood economic cycles in an idea that was born in 1905 and published in 1926, just after he got married, an idea that prophetically foresaw the cataclysm that would come three years later, in 1929. He found another epicentre of human misfortune, just like killing machines, in a human activity, stock market speculation. And he also found the path of this moral criticism

His wedding did not affect his relationships with his long-time friends, which included a circle wider than Miró and Esplá. He was also friends with Rafael Altamira, José Martínez Ruiz, Arniches, Chapí, Emilio Varela, Figueras Pacheco, Vicente Bañuls and Adelardo Parrilla, although he was not as close to them as with Miró and Esplá. Other people sporadically joined this circle of friends. His father-in-law José Guardiola Ortiz, Eduardo Irles, José Chapulí, José and Juan Vidal, Manuel Tormo Bernácer, his cousin Julio Bernácer, his brother Emilio Costa, Rodolfo Salazar, Eufrasio Ruiz, Heliodoro Carpintero, Rafael Bas, Esteban del Castillo, Agustín de Irízar y Góngora, Edmundo Ramos, Salvador Sallés, Luis Cánovas, whome were also joined by his friends born and raised in Madrid. During this stage of his life, the time when he was married and living in Alicante, he found peace of mind, just another child of the landscape, of the yellow and warm sun of friendship and of the astral king of his land. He saw happiness as a haven of peace and reflection, far from the frenetic pace of hasty pleasures and of the blinding lights of quick success. He liked nature and especially sunlight, the diffused and golden light that illuminates things, not directly looking at the blinding sun that damages one’s eyes. A natural product of this peace and this light are the works written with amazing simplicity and with transparent syntax, fleeing from the unbearable litter of useless scholarly syntax and blinding empiricism. He moved his home from Joaquin Costa Street (Reyes Católicos) to Alfonso El Sabio Street in front of the market and then to Plaza de los Luceros. Newlywed, among his varied economic readings, he found time to enjoy the work by Ibsen ‘Edda Glober’, which touched him. Meanwhile, Maruja became pregnant with their first child, who, when born, received the inevitable name of the protagonist of the novel: Heda, only with the Spanish spelling, without the invisible and soundless H: Eda.

Oscar Esplá, to whom he dedicated Society…, was Edita’s godfather, demonstrating his intimate friendship with Esplá and Miro. Eda would be the depository and guardian of these wells of family memories and would always accompany her parents during their lifetime. The second of the children, the first male, was Germán, who was named after his father in the customary way. This child was cheerful, open, outgoing, much like his father’s brother and diametrically opposed to his father. He remembers the people his father knew personally and through letters. Jokingly, he used to reread the letters from Robertson to his father, giving them a haughty English tone that caused spasms of laughter. He has worked for UNESCO in Chile for many years.

The third of his children was Ramón, the last to be born in Alicante. He was shy and physically resembled his father, especially his personality. He has brought together his father’s works and he prudentially centralised relationships with the researchers who have worked on his father’s scientific doctrines. If Society… was dedicated to Oscar Esplá, Gabriel Miró would have a place of honour in the enduring affection of Germán, proven by the fact as that Gabriel Miró’s real self, Ramonet, which German and Maruja knew, was bequeathed to their third son: Ramón. This child has retained an endearing affection for the now devastated and bald Sierra Aitana, spending time in Clot del Pi.

His youngest daughter, Ana María, was the only one born in Madrid, the second to last stage of German’s life. She studied to be a pharmacist, although she left her studies when she married Raimond Baineé. She lives in France, where she has started to translate the great book by Henri Savall Germán Bernácer: L’heterodoxy en Science Economique, since her siblings lovingly look over their father’s work.

Let’s go back to Alicante, where the married couple still lived. His father lived with them, but died two years after the wedding. The year was 1928 and two years later, another painful death occurred, the death of a close friend, Gabriel Miró. The year was 1930.

In 1923 he was appointed Secretary of the Alicante Chamber of Commerce, Industry and Navigation, a post held along with being a professor at the Business Studies School. In Alicante he was a prestigious man whose science was admired and recognised by educated people in society. His research work was reaching beyond the small borders of his province as he began publishing in economic science journals. In 1929, after publishing The Economic Cycle, he published Technique to Return to the Gold Standard: the Problem of the Price of Money. Both he and Keynes were obsessed with this matter. It was necessary to get rid of it. That same year, England had its issues with the gold standard, which, according to what was said, was one of the reasons behind the unforgettable fall of the stock exchange on Wall Street. The year his fraternal friend Gabriel Miró died (1930), he published an article in his friend’s honour in the magazine Sigüenza. The same year, he participated in the course organised by the Section of Economic, Financial and Monetary Issues of the Spanish Association of International Law. His specific contribution consisted of the conference ‘The Physiology of Money’.

Emilio Varela artist, and Gabriel Miró and Julio Bernácer, writers,member of the Alicante Circle.

26.5. The move to madrid

The second stage of Germán Bernácer’s life began in Madrid. His hiring at the newly-created Research Services of the Bank of Spain was irresistibly appealing for the economic scientist. The position was so attractive that even though he loved his land, the place where he had lived his entire 48 years, and had three children, and cherished his talks with old friends and was committed to his lab and his university chair, he nonetheless went. It was a painful move that he never got over. Any opportunity was a good one to go back to Alicante, and when he retired early, he went back to Levante.

The Bank of Spain was increasingly aware of the enormous importance of monetary issues. Regardless of the progress of economic theory, authorities were aware that assessing the economic situation, changes in magnitudes, calculations and so on were important insofar as they related to the skilful handling of domestic and international monetary issues. This work, entailing research, statistical and legal infrastructure support, was carried out by research services in other countries. The Banking Law of 1921 entailed greater complexity in the Bank of Spain’s task to handle economic issues and international relations. Thus, the creation of Research Services was imposed.

Research Services at the Bank of Spain was established in December 1930, at the initiative of Governor Federico Bas, and operations began the following year in January 1931. Approximately 12 months later, Bernácer was appointed head of Research Services. His appointment is on record on 7 December 1931 as per a resolution of the General Council. Julio Carabias was governor of the Bank at the time 161. It is clear that it would be an interesting experience for any scientist to practically inaugurate Research Services, thus creating the model for this new administrative and technical unit according to his image and likeness. However, this assertion will be discussed later on.

Research Services began to operate in quite an interesting way. There were two shifts, one in the morning and one in the afternoon. The first shift was led by José Larraz and was in charge of translating and classifying laws and bank statutes. The afternoon shift was led by a future great friend of Bernácer’s, Olegario Fernández Baños, and was in charge of creating index numbers and technical financial studies. Before the year ended, Larraz gave up his position, which was quickly requested by Germán Bernácer. Thus, in a strict sense, I can’t say that he was the first Head of Research Services at the Bank of Spain. At the time (1930), Bernácer was working as a professor of ‘Industrial Technology’ and in the position of Secretary General of the Alicante Chamber of Commerce, as mentioned above. When hearing that Larraz had left a vacancy, Bernácer quickly wrote a letter to the first Deputy Governor of the Bank, Mr Pedro Pan Soraluce, on 30 November 1931. The letter read: ‘Economically speaking, the position I would like is not any sort of improvement for me. My request is only a response to my interest in better satisfying my penchants and in finding an environment suitable to my favourite studies…’ The request was well-received by the Bank. On 7 December 1931, the Bank General Council agreed to his appointment. The agreement stated: ‘The management of Research Services is the responsibility of two heads…, one of them is Olegario Fernández Baños, who is currently deputy director, and the other is Mr Germán Bernácer Tormo, who is appointed to occupy the vacancy due to the resignation of Mr Larraz, agreeing that his duties will correspond to his degree of seniority at this bank…’. Bernácer, with much regret and much excitement, packed his bags and said farewell to his land and his friends; leaving his childhood, adolescence and maturity behind. He had a difficult time coping with the problem of his professorship, which he couldn’t attend to and which created a professional, emotional and economic void. However, he soon filled this teaching and professional space.