Bidding Against Yourself: “The You’ll Have to Do Better Game”

This is a favorite buyer approach (although anyone can use it), so if you’re selling, you need to be able to defend against it. If you’re buying, it’s a good one to use.

Let’s imagine a buyer whose company needs an automatic floor scrubber and a salesperson eager to make the sale. The list price for a full-sized floor scrubber is $7,000. However, since this equipment has a substantial margin, the salesperson can still make an acceptable profit at $5,000 (of course the buyer does not know this).

As a Buyer:

If you are the buyer, you will recall from our discussion in the section on setting the Maximum Supportable Position (MSP) that there are circumstances where it is to your advantage to place a specific offer or counteroffer on the table, and other circumstances where it is best not to. If you are in a circumstance where it is best not to, the “You’ll have to do better” approach can be very powerful. When you use it, your goal is to get the salesperson to make a series of concessions without having to make a counteroffer.

You can use statements such as:

“Come on, this price is way out of line. You are going to have to do better than that.”

“That’s really not very competitive.”

“Do you have any idea how much higher you are than your competitors?”

“Okay, I think we can go to $6500,”

You respond:

“No way, that’s not even close.”

“I don’t think so, you’re still not in the ballpark.”

The idea is simply to keep this up until the seller stops making concessions. When the seller does stop, you can say,

“Well, I still think you are too high, but you do have a good product so let’s do it.”

Alternatively, you can put a counteroffer on the table at that point and try to get the salesperson to go even lower.

As a Seller:

If you are the salesperson, playing the buyer’s “you’ll have to do better,” game is a slippery slide to nowhere. So when should you stop playing this game? Right at the beginning. You might make one concession down from the opening offer, a small one, at the start, but then, when the buyer says that’s not good enough, it is imperative to change the game. There are two primary ways to do this.

Option 1: Get the buyer to make a counteroffer. To accomplish this, you can use statements such as:

“Make me an offer.” [Strong]

“What did you have in mind?” [Moderately strong]

“Tell me what you need.” [Moderately strong]

“What will it take to get your business?” [Fairly weak and not recommended. Sounds too much like begging.]

Option 2: Change the subject.

If the buyer absolutely refuses to make a counteroffer, you can’t force them to, but then that is probably a good time to bridge to another subject and come back to price later. One excellent way to do this is to ask the negotiator’s favorite question, “why?”

Often this is totally unexpected. When a buyer says “You’ll have to do better,” they expect either a concession or refusal to make a concession. Asking “why” is a surprise, and can sometimes lead to interesting new information. As we discussed in the tactics section, people like to be fair and logical, or at least appear to be. When you ask why, the buyer might just jump in and tell you information you didn’t know.

For example, the buyer might respond “because I only have a budget of $3,000.” Then, in order to make this sale, you might now combine two strategies, the agreement in principle tactic and the problem-solving mode (see the following for details on both). You can respond:

“Well, if I could get you a floor scrubber that would meet your needs for $3,000, would you buy it?”

If the buyer responds:

“Sure, that would be perfect.”

We now have just reached an agreement in principle that the buyer is going to buy a floor scrubber if you have a smaller one that can do the job that you can price for $3,000.

Another way to change the subject is to focus on the price/value relationship. You might approach this by accepting the buyer’s need for a lower price but achieve that price in a way other than giving a price concession. For example, you might say:

I see that you always buy the premixed detergent rather than the concentrate, which saves time mixing. However, you do pay a hefty price premium using the premix, especially considering the area that you have to clean. The automatic concentrate blender that comes standard in this unit makes using concentrate a breeze and should save you $650 per year.

Or you can change away from price altogether. For example, you might go back to reviewing the customer’s total floor cleaning needs.

“Ok, let’s go back and make sure that I really understand your situation accurately.”

You would then go on to review the number of square feet that have to be cleaned, the manpower available, the time constraints for accomplishing the job, and so on.

Obviously you will have to return to price at some point. However, by moving to a different subject, you have the opportunity to reinforce your added value to the customer and to perhaps uncover useful additional information that will help in the price negotiation that you will have to return to. Finally, by changing the subject rather than simply making a concession, you are continuing the process of effectively managing the customer’s perceptions of your Least Acceptable Settlement (LAS).

Yes If...

Another important approach to concessions is what I call the “yes if” strategy. When you make a concession, try to get something in return.

“Yes, I can do that if...” What are the ifs? They are those things that you want, that the other party has turned down, or they may even be some things that you wouldn’t originally have proposed, but which you might be able to get them to throw in as part of the deal.

Yes, we could decrease the minimum order size to 100 pieces if we could deliver once a week instead of twice a week.

Yes, we could accept a 12 percent royalty rate if you’d be willing to reduce the upfront payment to $300,000.

Yes, we could reduce our prices by 1 percent if you’d be willing to be a demonstration site for us.

Yes, we could increase the warrantee period by six months if you would agree to be a demonstration site for us.

Always try to get something in return when you make a concession.

Oddly enough, when you make a concession to the other party, it is very helpful to be able to explain to them how and why you were able to do that. Go back to our floor scrubber example for a moment.

As we have said before, the good negotiator takes up residence in the other party’s mind. So imagine that you are a customer and you ask the seller to drop her price and she says:

“OK, we can go from $7,000 to $6,500.”

If there’s no reason or rationale for dropping the price by $500, what do you, as the buyer, think? Well, the first thing you might think is that $7,000 was a rip-off price. Instead of being happy, you might be annoyed. Remember, the seller’s MSP is supposed to be at least in some way supportable and credible. If she drops $500 from $7,000 to $6,500 and doesn’t have any rationale for doing so, how credible and supportable, in retrospect, does her $7,000 price look? Not very.

Worse yet, if she can drop $500 so easily, what would you think as the buyer? Can she keep on dropping her price? That certainly is the impression that she is leaving.

So work hard to try to explain to the other party, if you make a concession, why you are now able to do so, when before you couldn’t.

How do you justify a concession? Here are some possibilities:

Well, since you’ve agreed to purchase the three-year maintenance contract on the scrubber, I think we can justify reducing the price by $500.

If you can absolutely guarantee that the equipment will be here and functioning in 30 days with appropriate penalties if you fail to meet that deadline, I believe we can net 30 payment terms instead of net 45.

I know that it can be tricky sometimes to come up with a reasonable explanation, but the better you are at justifying your concessions, the more credibility you maintain and ultimately the happier the other party will be.

When you negotiate, the other side is always trying to read you, and to gather information from what you say and do. One of the things that they really watch is the pattern of concessions that you make. So you need to be aware that anytime you make concessions, you are sending information to the other party.

Take a look at what kind of information you might be sending. Remember, the process of managing the other party’s perceptions, which started at the very beginning of the negotiation when you were setting expectations, continues all the way through to the end. And one of the most important tools you have to manage the other party’s perceptions of your LAS is the way in which you make concessions. When you make concessions, you will always want to ask yourself, “What will they think I meant by that, and is that what I really want them to think that I meant?”

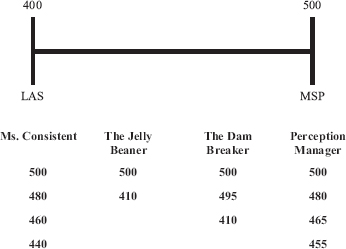

Let’s go back to our software licensing example. The salesperson has proposed a price of $500 per license and has run into some price resistance. If you look at Figure 15.1 there are four columns.

Ms. Consistent

The first column is labeled Ms. Consistent. As you can see, Ms. Consistent has dropped her price from $500 to $480, and then down to $460, and then to $440. Let’s even say that in each case she has in some way justified those concessions. Nonetheless, she is sending messages.

Figure 15.1 Concession patterns

Pretend that you are the buyer in this situation. Looking at that pattern of concessions, where do you think her LAS is? It’s not all that obvious, but certainly you suspect that it is divisible by 20. As the buyer, are you getting nervous? Do you think she has reached her LAS? Probably not. You just want her to keep on dropping $20 each time.

The Jelly Beaner

Now let’s look at the second column, which is labeled “The Jelly Beaner.” On the first line we have $500. That’s where we start. Let’s say our salesperson, Mr. Jelly Beaner, in his first concession, drops all the way down to $410.

OK, now, based on this concession, where do you, as the buyer, think Mr. Jelly Beaner’s LAS is? If he can drop all way down to $410 in one shot, he probably has a long way to go, don’t you think? Now if you remember from Figure 1.1 on page 4, the seller’s real LAS for this software is $400 per license. (That is the LAS for Ms. Consistent, Mr. Jelly Beaner and for the other sales people whom we will meet in a minute.)

Mr. Jelly Beaner is going to have to stop at $400. But what message has he sent? He may have sent a message that says, “I can go much, much lower.” When he actually does stop at $400, you as the buyer probably won’t believe him. In fact, we might even have a deadlock here, because the buyer might be convinced that Mr. Jelly Beaner can go much lower. Remember, no one will make a deal until they are convinced that they have reached the other person’s LAS.

Instead of properly managing the buyer’s perception of his LAS for the software, Mr. Jelly Beaner has completely mismanaged that perception. He may think that he has slam dunked this sale by giving the buyer a great price, but in fact, just the opposite may have happened. And even if he does pull off a sale at $400, he has still given away tons of his profit margin.

Why do we call this approach jelly beaning? Well it’s like this. Let’s say that you are on vacation with your family, out in one of the national parks. You are driving around, looking for wildlife. And you see some elk and that’s really neat, and then some moose and that’s really exciting, and then a whole herd of elk and more moose, and its starting to get a little boring.

But you still can’t find what you are really looking for—bears. And then someone says, “what’s that up in the field?” Somebody looks in the binoculars. “Wow, they’re bears.” And better yet, the road turns and works its way right up into the field where the bears are. And they are really cute, but they move awfully fast for large animals, except for the one sitting right in the middle of the road. It’s not moving. And you’re not moving.

And the bear pawing at the window has very large teeth, and the family is beginning to get a little nervous. And someone says, “Why don’t you open up that bag of jelly beans and give it a jelly bean? Maybe it’ll go away.” So you open the bag of jelly beans, open the window a crack and the bear—whoosh—takes the jelly bean. Does it go away? Not likely.

“Give it some more, you didn’t give it enough.” So you open the window a little more and give it a handful of jelly beans. The bear—whoosh—takes the jelly beans. Does it go away? Pretty soon, that bear is in your car, in your lap, eating out of your bag of jelly beans. And does the bear say, “thank you?” Not likely. What does the bear say? “More.” And so appeasement just doesn’t work, either with bears or in a negotiation. All it does is whet their appetite for more.

The Dam Breaker

In our third column, which is labeled “The Dam Breaker,” let’s say that again we start at $500, and this time our salesperson’s first concession is down to $495. And then the salesperson panics, the dam breaks and the next concession is $410. The dam breaking is a variant of jelly beaning and again is likely to convince the buyer that our salesperson can go well below $400.

The Perception Manager

Now let’s look at the last column, which is labeled “the Perception Manager.” Here our salesperson is being a lot more thoughtful and careful. She has done her planning and worked on the Information to Find part of the process in order to make a guess as to the buyer’s LAS. She knows who her competitors are and what their prices are likely to be. She knows her added value versus the competitors and something about the customer’s needs and pressures and how the customer looks at the world.

Based on all of that, she guesses that the customer’s LAS is somewhere between 435 and $450 for this software. She doesn’t know exactly, but that’s her best guess. So let’s look at how she proceeds in the negotiation.

She starts at $500 and her first concession is down to $480. Then she goes down to $465 and then to $455. If you are the buyer, based on that pattern, where do you think her LAS is? Are we getting close to it? Most people would say her LAS is somewhere in the $445 to $455 range. She is working to manage the customer’s perception that her LAS is right about in the same place as where she guesses the customer’s LAS is. Of course, her real LAS is still at $400.

So always remember that the pattern of your concessions provides information to the other side.

Now perhaps you are thinking, in negotiations in our industry, we don’t have that many offers and counteroffers. Things tend to move more quickly. But even then, the process works the same. Just faster. Let’s imagine that there are three houses for sale, one each in towns A, B, and C. There is no particular connection between these three houses except that we are observing these negotiations. Each house is listed on the market at $200,000. And each house has an interested buyer who has offered to buy it at $175,000.

The homeowner in Town A counteroffers at $181,000. Where do you think the final outcome will be if they reach agreement? And let’s say that the homeowner in Town B counters at $189,000. Where do you think they will end up? And the homeowner in Town C counters at $196,000. Where do you think they will end up?

In each case you made a guess as to where the sale would close based on that first counteroffer of the homeowner. Everybody does this. It’s called tracking behavior. Everyone automatically, mentally tracks to the end point of the negotiation based on early offers and counteroffers.

So you are sending powerful messages right from the beginning. In fact, your first concession sends perhaps the most powerful message. Make sure that it is sending the message that you want to send.

Another approach that people sometimes use to try to close a deal is split the difference. It can be a really good strategy or it can be a disaster. Imagine a house listed for $400,000, with an offer of $340,000 for the house. And, let’s say the seller is very impatient. So as soon as the $340,000 offer comes in, the seller says to his broker, “Tell them that I am willing to split the difference.”

Since the house is listed at $400,000 and the buyer is offering $340,000, splitting the difference would be at $370,000. Is this a good move by the seller? Well, if I’m the buyer, what do I now know about where the seller’s LAS is not? Before the seller offered to split the difference, I probably had no idea. His LAS could be at $395,000 or at $390,000 or wherever. But the moment the seller says, “split the difference,” I know that his LAS is not above $370,000 since he is willing to make a deal there. It could in fact be right there, but my guess would be that it is probably even lower.

The response of the buyer might be, “You’re not in the ballpark yet, in fact, you’re not even in the parking lot, but in recognition of the fact that you are on the right road I would be willing to go up to $345,000. Do you want to try that split stuff again?”

You see, when we are far apart, splitting the difference is just like jelly beaning. It is the impatient negotiator’s attempt to get out of the process and move quickly. And as I said earlier, the impatient negotiator almost always does poorly.

Now let’s say that instead, over the course of several days, both sides had made several offers and counteroffers. The seller has come down to $379,000 and the buyer has come up to $377,000.

Could we use split the difference here to close the deal? Sure. The time to use split the difference is when we are really close, never when we are far apart.

Split the difference can be particularly useful when we are very close but both sides seem to have dug in and nobody is going to make that final, little concession that would close the deal. The reason is that the last thing that happens in a series of events is what sticks in our mind. Therefore, if I make the last concession, it feels more like I lost.

This is really a type of ego problem. By splitting the difference, both sides make that last little concession and everybody is happy. But only do it when you are really close. Otherwise it’s just the jelly beaning.

Silence (Again)

As discussed elsewhere in this book, silence is a tactic that can be used effectively at several stages of the negotiation. It is critical that you use it appropriately when concessions are being made, either by you or the other side. For example, suppose the issue is the minimum order quantities for a given level of pricing.

“I really think that a minimum order quantity of 100 pieces is too high given our situation here. I’d really like you to consider a minimum order quantity of 25.”

“Unfortunately, we simply can’t do that. We might, however, be able to go to 90 pieces.”

The buyer hesitates a moment.

“Well…”

“OK, if I really pushed maybe I could get it down to 70 pieces. Would that work for you?”

The impatient salesperson jumps into the silence with another concession, going down to 70 pieces.

Once again, patience is key in a negotiation. Never, ever interrupt someone as they are about to make a concession. Never jump in and make another concession, just because there’s a pause in what they say. If you make a concession, sit there and wait. See what they do with it before saying anything else.

The Hovering Pen or the Nibble Strategy

You have worked long and hard to reach an agreement. Finally, you think everything has been agreed to and that all you have to do is write it up and sign it. You are blissfully contemplating the hero’s welcome that you will receive when you come back to the office with the signed agreement. Then suddenly the other party “just happens to remember” some small item that you hadn’t resolved.

You know, it occurs to me that we never really did finalize the issue of how long the warranty would be. Six months is really short. Don’t you think we could move that up to 12 months?

Moving from a 6-month warranty to a 12-month warranty is not that big a deal, so you agree. Nothing should stand in the way of getting this deal finalized now. Unfortunately, it doesn’t stop there.

That reminds me. We did agree that the minimum order quantity could be 10 units and not 50, right? And you will pick up the freight charges, even if the order is only 10 units, right?

You are starting to get a little nervous. You don’t want this sale to get away, so of course you give in. While you are waiting for the revisions to be included in the agreement, the buyer brings up a few other issues that they also want to discuss with you. And so it goes.

You are the victim of the Hovering Pen strategy, also called the Nibble.

As far as you are concerned, you had a done deal. As far as the buyer was concerned, the negotiation was far from over. They are just using your anxiety to get the sale closed in order to extract additional concessions.

So how do you defend against the Nibble? The first key is to remember what Yogi said: “It not over till it’s over.” Nothing is agreed to until everything is agreed to. You see, if you count this as a done deal, then the Nibble looks like just a little impediment. You know you have the deal done, and well, you can throw in the little Nibble, that’s OK. And then there’s just one more. And then just one more. And you’re heading down the slippery slope to nowhere until you realize that you’ve got a Nibble game going on.

When you get that first Nibble, make a mental switch—hey, this isn’t over, we’re still negotiating. It’s just taking on a new form. The best way to deal with the Nibble is to nip it in the bud. There are several ways you can do that.

If you’re selling and it is a buyer who is using the Nibble, you can counter with what we call the purchase order close.

I’ve given you the best deal we can, but I’ll tell you what: If you write up a purchase order and include that one little extra thing you wanted, I’ll see if my boss will approve it. I know he won’t approve it if I just call him up and ask him, but if I have that signed purchase order, maybe he’ll just say OK.

If the buyer agrees, you will stop the Nibble game with just one little item, and you have a signed purchase order and the deal is done.

A second approach is to just say no. Sometimes, a polite but firm no will end the process right there. How many times have you heard the other party say,

“Well, it never hurts to ask.”

A third approach is to start to reconfigure the deal. You might say,

“If it’s really important to you, we might be able to do that, but the only way I could would be if we went back and changed something else.”

What you’re doing here is saying, “Look, you’ve reached my LAS. I gave you my best possible deal. If I’m going to give you something else, I have to take away something somewhere else.” In other words, you’re continuing to work to manage their perception of your LAS. When you say, “Yes, I’ll give it to you but we’ll have to change something else,” that’s a pretty credible message that you really have reached your bottom line.

Of course you can use the Nibble strategy yourself toward the end of the negotiation. And if the other side doesn’t see what you’re doing, it can be a very effective strategy to obtain a few extras.

Final Offer

I don’t really like the words “final offer.” I think you run the risk of being hurt both if it is your final offer, and also if it’s a bluff.

“I’m afraid we really have reached the end of the road here. What I have on the table is my final offer and that’s the best I can do.”

That might be okay if you really have reached your bottom line. However, if you are still bluffing and you have not yet reached your LAS, you face problems of credibility if you later discover that you have to make some more concessions in order to close the deal.

You can use the words “final offer” when you have reached your LAS, but even here, there is a potential danger if you negotiate with the same individual frequently. If they recognize that you only use the term “final offer” when you have reached your LAS, they will simply negotiate with you until they hear those magic words.

All in all, it is probably best to use the words “final offer” or their equivalent very infrequently if at all.

When the other party uses final offer or something similar, I start to get nervous that they may be backing themselves into a corner that they can’t get out of, particularly if I think they really have more room to go. Then I will try to say things to move them out of the corner such as:

Oh, I don’t know if we should really be talking about final at this point. You know there are so many ways that we can make this happen. Let’s just keep an open mind and see if we can come up with something that will work for everybody.

The LAS Magnet

One final point on concessions. A researcher once decided to do an experiment. He recruited about 120 people over a period of time and had them conduct simple buy-sell negotiations. Half of the group were buyers and the other half sellers. In each case he gave the buyers some simple instructions about their situation, their needs and how high they could go. All of the buyers got the same instructions.

The sellers were also given some simple instructions about what they were to do. However, the researcher split the sellers into two groups. The sellers in Group A were told their MSP and also their LAS. In other words they had the full Settlement Range and knew how low they could go.

The Group B sellers were told their MSP but they were not given an LAS. Instead, the instructions just said, “start here at your MSP and get the best deal you can.” After all of the negotiations were completed, the researcher analyzed the results and found that one group of sellers did significantly better than the other.

Which group of seller do you think did better? Well, Group B, the group of sellers that did not know their LAS, did better. Why? The problem for the Group A sellers was that they knew how low they could go, that is they knew where their LAS was, and it tended to act like a mental magnet, pulling them down to their bottom line.

We call this phenomenon the LAS Magnet. The Group B sellers, on the other hand, didn’t know their LAS, and therefore they tended to concentrate on their MSP and the buyer’s LAS.

I was curious as to whether I could replicate these results. When I conduct programs for large audiences at conferences, I always start with a quick and simple role play negotiation where a tourist is negotiating for something like a vase or a rug with a local shopkeeper.

To duplicate the experiment, I have sometimes told the shopkeepers that they could not remember what they had paid for the article and therefore they didn’t know its proper LAS. I just told them to do the best they could. Invariably the group of shopkeepers who did not know their LAS reached agreements that on average were 10 to 15 percent better than the shopkeepers who did know their LAS.

Of course this does not mean that you should not know your LAS. It is absolutely essential that you know it, because it’s the barrier you can’t cross and it keeps you from making a bad deal. On the other hand, you need to be very careful not to fall into the LAS Magnet trap.