8

Principle of Rights

Introduction: Rights of Individuals, Groups and Classes

We, as individuals, groups and classes, require liberty and freedom for exercising our choices w.r.t. skills, business or place of residence, to move freely in the country choose our representative in a free and fair election. Liberty and freedom are also required for self-realization and development of our faculties and capacities of expression, speech, belief, opinion, etc. It is needed for self-mastery through protection of life and personal liberty and freedom to pursue our moral, ethical and intellectual ends with dignity and without exploitation or oppression.

Rights, as claims of individuals, groups and classes, are made against either the society or the state. For example, a society may recognize the right of a member to choose his/her partner in marriage without consideration of birth or gender, or may recognize the right to choose from only a particular group (caste, religion, ethnicity) or gender. To sustain or enforce the limits of rights, which it recognizes, society may employ various social, moral, religious and cultural mechanisms of control. However, society does not have the means of legal and coercive enforcements, such as laws, courts, police and prisons for enforcing rights. This would be possible only if the agency, which has the means of legal and coercive enforcements, recognizes the claims of individuals, groups and classes. This agency is the State. Further, it is possible that certain claims of individuals/groups/classes, which are necessary for self-development, dignity and for exercising choices, are not recognized by the society due to historical and ideological biases or dominance of a few in social set-up or gender bias. This requires the State to correct it by expanding the scope of rights. Most of all, the State must recognize a set of rights to define limitations on its authority and obligation of the citizens. There is a significant difference between the rights recognized by the society and the State. In case of clash between the rights recognized and permitted by the society with the one recognized by the State, the latter prevails. This is due to the legal sanction behind the rights provided by the State. Rights are a corpus of recognized and guaranteed conditions provided by the State for enjoying liberty by individuals/groups. As such, rights properly called are claims of individuals and groups recognized by the State.

Besides the claims of individuals, the State recognizes the claims of minority, cultural, ethnic, religious and linguistic groups, and various classes. Recognition and protection of the rights of groups and minorities in society are required to maintain peace, harmony, order and mutual co-existence in a multicultural society. Moreover, such recognition could also be in appreciation of culturally specific values.

Supporters of multiculturalism and cultural relativism advocate equal/fair opportunity to all groups for participation in the affairs of the State and recognition of relative significance and value of groups in society and their protection. Pluralists argue that the rights of the groups in society should be recognized and protected. This is because these groups have corporate personality and are as important as the State. J. S. Mill advocated freedom of the individual and minority against the overwhelming dominance of the opinion of the majority in society. This, he felt, would be required in the interest of moral and self-development of the individual. The rights of different classes, such as the bourgeoisie were the rallying point for the English and the French revolutions and of the working class for the Communist revolutions across the world.

The Constitution of India recognizes a set of rights and liberties of religious and cultural groups along with that of the individuals. Chapter III of the Constitution of India on Fundamental Rights is a charter of not only individual rights and liberties but also that of the cultural and religious groups.

Rights could be claims of individuals or groups or classes against the state, the society or a group. It must be recognized and enforced by the state. Right to vote, right to freedom of speech, expression, etc. and right to information are claimed against the state. Rights provided under Article 17 of the Constitution of India relating to ‘abolition of untouchability’ is a right of social groups against the society. It removes social disabilities based on birth in terms of castes. Similarly, prohibition of forced labour or child labour are rights against the society.

If rights are claims of individuals and groups recognized by the State, then what are the grounds upon which these claims are based? A variety of grounds such as moral, legal, natural, human, historical, social welfare, etc. have been suggested as basis of rights. Primarily, claims of individuals to be recognized as rights should be such that they are generally applicable. In other words, claims should not amount to privileges for some. However, there could be claims of minorities and under privileged groups that are to be recognized as rights.

Historically, the concept of rights has stood for ‘privileges as in the rights of the nobility, the right of the clergy, and, of course, the divine rights of the kings’.1 And also for the rights of the slave owners, the privileged classes. But in contemporary parlance, rights are basis of relationship between the State and the individual. This relationship is reflected in the concept of citizenship. Citizenship is a legally defined identity of a member of the State. It is based on the principle that individual members of the state are equal before the state, irrespective of their social, cultural, religious, linguistic or ethnic backgrounds. The state confers rights upon the citizens as individuals; it can also engage differently with different groups of citizens and confer on them separate rights, e.g. minority rights. To confer separate rights to different groups is to subscribe to principles of positive discrimination, social justice, multiculturalism or cultural relativism. Thus, discussion on rights includes grounds of rights and associated political obligations; which of the rights should be possessed by whom and which group(s); what are the principles of distribution of rights amongst the members and groups; what are the grounds and defence of human rights; and how are rights related to liberty on the one hand and justice on the other.

A group of contemporary writers such as Michael Sandel, Alasdair MacIntyre, Charles Taylor, Michael Walzer and others have taken a position that each individual develops an identity, talent, pursuits in life as a member of community only. They are critical of the libertarian position, which treats the individual as autonomous rational and moral agent. These writers are known as communitarians, because they seek to root the identity and choice of the individual in the life and identity of the community. They apprehend that if individuals are allowed to realize their rights as autonomous rational and moral agents, as libertarian advocates, there could be social and moral disasters. In a sense, communitarian position amounts to the argument that rights of the individuals should be recognized as part of a community and not as autonomous choosers.

However, there is problem in the communitarian position of recognizing rights of individuals merely as part of a community. By virtue of the fact that communitarian position suggests that the individual ‘discovers’ personal identity as community, it limits the choice about beliefs, associations and attitudes. Amartya Sen in his The Argumentative Indian, pointing to the dangerous implications communitarian position can result in, says, ‘Many of us still have vivid memories of what happened in the pre-partition riots in India just preceding independence in 1947, when the broadly tolerant subcontinentals of January rapidly and unquestionably became the ruthless Hindus or fierce Muslims of June. The carnage that followed had much to do with the alleged ‘discovery’ of one's ‘true’ identity, unhampered by reasoned humanity.’2 While the debate on whether right of the individual should be recognized as part of the community or as an autonomous chooser is still on, we are faced with another tension.

The tension between universal standards of rights of human beings and those, which are culture-specific, have been a matter of intense debate. Internationally, the debate has revolved around the arguments and counter-arguments over the primacy to be given to the rights based on individualism or culturally specific values. The Western countries term many of the non-Western countries as violators of human rights. On the other hand, countries such as China and others have argued that there should not be judgement on upholding or violating human rights, as they are culturally specific. Many groups and activists have even tried to equate the issue of caste discrimination in India as ‘racialism’ and have raised it to the United Nation forums recently, while the Constitution of India has already addressed the issue. Another example is the debate in India on the need for a Uniform Civil Code. The Personal Laws, defining the civil rights and obligations of members of certain religious communities, particularly, the Christians and the Muslims, have been attacked by many, arguing that it should not exist in India, which has a secular constitution. Someone who champions the rights of individuals (liberal position) can argue that there should be a uniform civil code defining the rights and obligations of each individual irrespective of their membership of different communities. This is because relationship of each individual with the Indian State must be defined uniformly as citizen and not as members of religion, caste or linguistic groups. But others may also be right in arguing that culturally and religiously specific rights of the people should be protected (cultural relativist position). In their view, the Indian State may be right in relating itself with different members differently.

Definition and Meaning of Rights

Defined and interpreted differently by writers and thinkers, rights are moral and legal entitlements or claims of individual or groups against society, state or a group of individuals. Rights could be claimed on various grounds such as inherent human personality, natural basis, legal basis, moral and idealist basis, historical basis, social basis, etc. Generally, society or community admits certain claims of individuals and groups, which, in turn, are recognized by the State. The State gives sanctions to these claims either wholly or selectively. It is also possible that certain rights are introduced by the State itself and did not arise from a given society or community. For example, voting right in India was introduced as a result of adoption of a particular form of government—Westminster model of parliamentary democracy. Various rights sanctioned by the State could also be against prevalent social and religious practices. Right to adult marriage means that a minor should not be deprived of her/his right not to be married before attaining a certain age. This could be against the practice of child marriage followed by some sections in society. Similarly, right to widow remarriage, right to not to be discriminated on the basis of birth in a particular caste are rights for the individuals and groups introduced by the State.

Rights can be understood differently, in terms of claims, liberty, power, privileges and immunities, etc. Rights could also be associated with the end they serve. Rights serve the purpose of providing conditions for liberty and development of capacities of personality of individuals. For example, freedom of expression and speech constitute liberty of a person to express his or her views, ideas, feelings, etc. However, to secure this liberty or freedom of each individual against the other and also against the state, some safeguard is required. Rights provide this safeguard. Rights of citizens are also necessary to promote limited and constitutional governments. Provision of rights is considered as one of the limits put on the State. J. S. Mill in his On Liberty, while tracing the history of ‘struggle between Liberty and Authority’, mentions that ‘by obtaining a recognition of certain immunities called political liberties or rights’, a limit was put to the power of ruler or king.3

Rights Defined

T. H. Green, an idealist and advocate of positive liberty, in his Lectures on the Principles of Political Obligations has defined right as ‘a power of acting for his own ends … secured to an individual by the community on the supposition that it contributes to the good of the community.’ Power of acting for his own ends implies that Green sees right as power, as capacity or empowerment to act for certain ends that the individual seeks. These ends are self-realization and fulfilment of moral nature of human beings. According to Wayper, Green believes that men have certain claims, which ought to be recognized as rights, if man is to fulfil his moral character. Green calls these rights as ‘Natural Rights.4 However, his conception of natural rights is not like the one contractualists spell. They arise not from state of nature but from moral character of men. The fact that rights are important for the individual is obvious from the first part of Greens definition. Moreover, these are also beneficial for the community. He believes that will and common consciousness of common good, and not force, are the basis of the State. As such, moral character of human beings must be realized and the community must secure rights. It is clear that only the community can secure rights and in securing them it supposes that rights secured to individuals are in the interest of the community as a whole.

Leonard T. Hobhouse views rights in terms of coordinated rights. He says, ‘the system of rights is the system of harmonized liberties.’ This means, liberties secured by rights of one must be restricted by the rights of all.

Ernest Barker, a pluralist and advocate of positive liberty, in his Principles of Social and Political Theory, defines rights as ‘external conditions necessary for the greatest possible development of the capacities of the personality.’ Barker defines rights in terms of conditions that help in development of the capabilities of personality. He measures the quality of rightness and justice of law of the State in terms of securing and guaranteeing to the greatest possible numbers of persons the external conditions necessary for the greatest possible development of the capacities of the personality. These secured and guaranteed conditions are rights. Barker adds a criterion of greatest possible numbers of persons to whom rights must be at least secured and guaranteed. This means allocation of rights requires distributive justice, which, in turn, requires application of principles of liberty, equality and fraternity. According to Barker, rights of a person are the result of the general system of rights. That is, rights of a particular person are capacities of that person of enjoying some status as a share of the whole. To clarify this point, Article 19 (g) provides the right to practice any profession, or to carry on an occupation, trade or business. Do a business leader and a pedestrian cycle repairer equally share this right? The answer is no because their external capacity to enjoy this right is different. Thus, Barker concludes that rights of a person are the whole of his/her capacity, whole power of actions within the State. The sum total of rights enjoyed by a person determines his/her legal personality. Distribution of capacity or power of action should be such that it serves the greatest possible number of persons. This calls for principle of justice and equality.

Laski in his, A Grammar of Politics, defines rights as those conditions of social life without which no man can seek, in general, to be his best.’ Laski, though associated with varied political and intellectual streams, advocates positive liberty and puts a premium on the self-development of human beings. He identifies rights with conditions of social life that help human beings realize their best self. He says that the State exists to help human beings achieve their best selves and this can be secured only by maintaining rights. This leads him to conclude that every state is known by the rights that it maintains. In brief, Laski maintains that the end of the State is to make possible those conditions of social life, which help human beings achieve their best selves. These can be secured with the provision of rights.

In defining rights Green, Barker and Laski, all emphasize on two components of rights: (i) certain external conditions to be secured by the community or the State and (ii) development of self and capacity of human beings. This means that interests of the community, society or the political order, i.e., the State and that of the individuals are not very opposed. However, the main focus is on securing rights so that individuals seek their best. R. N. Gilchrist in his Principles of Political Science, echoes similar views when he says, ‘Rights arise … from individuals as members of society, and from the recognition that, for society, there is ultimate good which may be reached by the development of the powers inherent in every individual.’ Gilchrist underlines the social aspects of individuals seeking their best. Rights will help individuals develop their powers that, in turn, serve the ultimate good of society. Social recognition and community securing individual rights is important but essentiality of recognition of rights by the State is also to be appreciated. Without legal back up rights may not be quite exercisable. Rights in one person require that his/her freedom of action is guaranteed by a penalty which prevents another person from violating it.

Ingredients of Rights

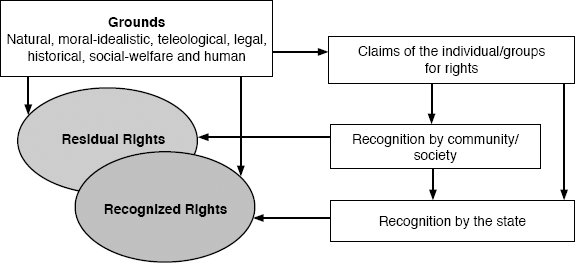

Relationship amongst the ingredients of rights suggests that claims emerging on various grounds could be recognized by the State as rights. Although this may not be coterminous with what all rights individuals and groups perceive they should enjoy in society. For example, many states may not accept the right to self-determination of various ethnic groups. It appears that individuals can make claims and demand rights on various grounds. Some of these claims or demands may remain with society and some others can be duly recognized by the state. Some rights of individuals may be recognized by the State even though there is no consensus in society, e.g., right to sexual orientation, abolition of sati practice in India, etc. These could be recognized and residual rights (see Figure 8.1).

Let us start with the three declarations that championed rights of all human beings to understand what are the grounds on which rights are claimed and what types of rights are provided for.

- ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident. That all men are created equal. That they are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights. That among them are life, liberty and pursuit of happiness. That to secure these rights, governments are instituted by men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. That whenever any form of government becomes destructive of those ends, it shall be the right of the people to alter or abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation upon such powers in such form, as shall seem to them most likely to effect their safety and happiness.’5

(The American Declaration of Independence, 1776)

- ‘Men are born and always continue free and equal in their rights … Government is instituted in order to guarantee to man the enjoyment of his natural and imprescriptible rights. These rights are equality, liberty, security and property. No kind of labour, tillage, or commerce can be forbidden to the skill of the citizen. Every man can contract his services and his time, but cannot sell himself nor be sold: his person is not an alienable property … society owes maintenance to unfortunate citizens, either procuring work for them or in providing the means of existence for those who are unable to labor … Education is needed by all. Society ought to favor with all its power the advancement of public reason and to put education at the door of every citizen. …’6

(The French Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, 1789)

- ‘Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world … All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in spirit of brotherhood … Everyone … has right to social security … is entitled to realization … of the economic, social and cultural rights indispensable for his dignity and free development of personality … Everyone has the right to work … right to form and join trade unions … standard of living … right to education … freely participate in the cultural life of community …’7

(The UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948)

All the three declarations quoted here, talk of natural, inalienable, or imprescriptible rights of man. The claims for rights of human beings have been made on the grounds of certain rights available to human beings even before the State comes into being. As such, natural rights are inalienable and states should recognize them. Moreover, the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948 recognizes inherent dignity of human beings also. Thus, ground of natural rights and inherent dignity of human beings have been invoked to advance the cause of rights, such as life, liberty, property, security, equality, etc. Many of the rights proclaimed in the French and the UN declarations are in the nature of social welfare also such as social security, education, etc. Further, the American and the French declarations require that governments instituted by the people should secure and guarantee the natural rights. As such, natural rights to be secured and guaranteed by the State must become recognized rights as well. Natural rights invoke natural ground for getting recognition by the State, which means natural rights are converted into positive rights. UN Declaration recognizes ‘inherent dignity’ of all human beings. Rights are required to protect, develop and realize the dignity. This is the teleological ground of rights of human beings where rights inhere in the very character of human beings.

Positive and Negative Rights

There could be certain rights in which the State is not authorized to interfere with individual. They consist of what remains after taking into account all the legal restraints that impinge upon an individual. Rights, which arise due to authorities not interfering, are negative rights. In other words, an individual has rights because public authorities are not authorized to interfere without statutory authority. These could be civil, cultural, religious or social rights. For example, the individual's right to freedom of expression and thought, right to religious belief, freedom of assembly and association, freedom of contract, etc. are negative rights.

Certain rights may require the state to take up positive actions for guaranteeing and securing rights of individuals or groups. For example, right to work, right to universal education, right to housing, right to legal aid, etc. They are positive rights, as these require the state to provide positive conditions for securing these rights.

Under Article 19 of the Constitution of India, the rights provided are in the nature of negative rights, as they are available against State action for the protections of freedom mentioned therein. Austin says, ‘the Fundamental Rights of the Constitution are, in general, those rights of citizens, or those negative obligations of the state not to encroach on individual liberty, that have become well-known since the late eighteenth century and since the drafting of the Bill of Rights of the American Constitution…’8 For example, right to freedom of speech and expression, peaceful assembly, association/union, free movement, residence and settlement, practise any profession, occupation, trade or business, etc, are due to absence of interference. There are reasonable restrictions that the State can impose in favour of certain rights.

Right to know, which flows from the requirement of freedom of speech (you cannot speak relevantly if do not know and are informed), may fall under positive rights, as it requires positive action from the State. On the other hand, interpretation of Article 21 of the Constitution of India relating to ‘protection of life and personal liberty, has led many courts to include right to shelter9 (1987), legal aid (1979, 1986), livelihood (1994) in this category. These are positive rights, as they require certain action on the part of the State.

The Indian Constitution contains both negative as well as positive rights. Negative rights are in the nature of securing civil liberties through non-interference by the State in the conduct and action of the individuals. Positive rights are in the nature of state's positive obligations.10 Rights contained specifically under Article 19 relating to freedom of speech, etc. and Article 25 relating to freedom of conscience, religion, etc. are in the nature of negative rights. Given the specific condition of the Indian society, the rights provided under ‘prohibition of discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth’, ‘equality of opportunity in matters of public employment’ including provision for positive discrimination, ‘abolition of untouchability’, ‘protection of life and liberty’ have been judicially constructed to include livelihood, shelter, legal aid, and ‘prohibition of employment of children in factories’. These are examples of positive rights. However, many positive rights relating to welfare of the people, living wages, free legal aid, right to work, right to education have been assigned to Directive Principles of State Policy, which are not fundamental.

Conventions of Guaranteeing Rights

The way rights of individuals and groups should be secured and guaranteed has been attempted differently. In some countries, rights are in the nature of Residual Rights as in England; in another, they are protected as Bill of Rights as in USA and yet another, as Fundamental Rights as in India. There have been different conventions of securing rights by either limiting state interference or invoking positive obligations. We may discuss three significant systems or frameworks of providing legal rights in the UK, USA and India.

In England, the Constitution does not provide any charter or bill of rights or fundamental rights. Rights are in the nature of residual rights and are within the framework of Common law. This means, the individual has rights so long as public authorities do not interfere; do everything that is not forbidden. Rights are remains of what legal restraints take away. This mostly protects the individual from the executive. Parliament, however, is sovereign and as such can literally legislate to take away rights of the individual. Thus, rights are subject to infringement under Parliamentary supremacy. Even the British Court cannot override the same. Rights of the individual, in fact, are grounded only on ordinary law of England and are not provided through Bill of Rights or as fundamental rights.

William Blackstone in his Commentaries on the Law of England identified three rights in English law, namely the right to personal security, the right to personal liberty, and the right to private property. A. V. Dicey also demonstrated that rights were to be derived from the rule of law, as right to personal freedom, freedom of discussion and the right to assembly. Which rights should become part of common law has been a matter of debate in England.

It has been suggested that the UK should also enact a statutory ‘Bill of Rights’. It has been argued that incorporating European Convention on Human Rights (1950) into domestic law could serve this purpose. With enactment of Human Rights Act, 1998 in the UK, rights have been given the status of statutory rights. However, unlike the Bill of Rights of USA, the British Parliament is allowed to infringe the Act.11

The American Constitution guarantees rights through the Bill of Rights. The Bill of Rights is a corpus of rights that defines the scope of civil liberties and limits the legislature and the executive from interfering in the rights of the individuals and groups. In England, Parliament is sovereign in interfering in the rights of the individuals. In America, both executive and legislature are limited from interfering. The American Judiciary with its supremacy keeps a check on both the executive and the legislature from violating the rights provided in the Bill of Rights. The American Congress and Senate cannot infringe the Bill of Rights by invoking the ‘emergency or danger to the state’ clause. The ‘declarations in the American Bill of Rights are absolute and the power of the state to impose restrictions upon the fundamental rights of the individual in collective interests had to be evolved by the judiciary.’12 Thus, Bill of Rights provides a check on the executive and the legislative from interfering with the given rights of the individual. Judicial supremacy is a check on both the organs.

It may be mentioned that most of the states in America had the Bill of Rights on the time of their joining the American federation. They insisted that the Constitution of the United States of America should also have a list of rights. It was as consequence that the first 10 amendments that were carried out in the American Constitution included these requirements.13

The Indian Constitution provides for a charter of ‘Fundamental Rights’ that defines the rights provided to the individuals/citizens and various religious, cultural, linguistic and ethnic groups. Fundamental rights have been made enforceable and justiciable by provision of writs under the fundamental rights section in the Constitution. They are protected from both executive intervention and also unnecessary interference from the legislature. However, though judiciary has right of judicial review, legislature is supreme in the matters of legislation on fundamental rights. Further, in times of national emergency or on the basis of reasonable restrictions, the state can impose limits on the fundamental rights.

The Indian Constitution also provides for ‘constitutional rights’; right to property is a constitutional right. These are not enforceable under the fundamental rights category. Restriction imposed by the state on such rights cannot be challenged on the basis of unreasonableness. However, persons cannot be deprived of constitutional rights ‘save by authority of law’.

Rights contained in the Human Rights Act (UK), Bill of Rights (USA) and Fundamental Rights (India) are enacted, legal and positive rights, which are enforceable in courts.

Forms of Rights

Rights as claims or entitlements imply legal relationship between the individuals or the groups and the State or amongst the individuals and groups themselves. Morality and immorality of a claim or entitlement may not have to do anything with legality or illegality of the same thing. For example, till the Child Labour (Eradication and Rehabilitation) Act or for that matter, Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, were passed in India, both child labour and women trafficking were inhuman in the sense that they were against the inherent dignity of children and women, respectively. But they became illegal and hence criminal only after they have been legally banned. As such, an act or practice may be inhuman or immoral but may not be illegal and hence criminal.

Human Rights, being the inherent right of human persons must have been inherent ever since the two-legged social animal has walked on earth. But to be legal, it must be recognized and backed by state sanction. Thus, we have human, legal and moral rights. The human and moral rights can be the basis for legal rights.

Wesley Hohfeld in his Fundamental Legal Conceptions as Applied in Judicial Reasoning has identified four types of legal relations. He prefers to describe these as entitlements.14 Firstly, there is a claim right where one person asserts that s/he has claim on another. A claim right imposes mutual or corresponding duties or obligations. For example, a person's right not to be treated as ‘untouchable’ requires and obligates another person to uphold this claim. Secondly, a liberty right authorizes a person to do as s/he pleases; at liberty to do it. For example, to use a pedestrian or a road (of course not toll roads) or smoke (except where ‘No Smoking’ zone is declared) are liberty rights. Thirdly, powers as rights are legal abilities or empowered or enabled positions. It empowers someone to do something, for example, to vote (voting right), to get elected (right to occupy public office), to get employment (right to equal opportunity in employment), etc. Fourthly, Hohfeld mentions immunities, which protect a person from the power of another. For example, the right of the elderly not to be drafted/conscripted by the state into the army; diplomatic immunity of dignitaries in host countries, etc.

Hohfeld is of the view that right in the strict sense should be confined to a claim right. This is because it imposes corresponding duties or obligations on another. Possession of a claim right consists of being legally protected against another's interference. A liberty right poses no such corresponding duty or obligation.

Discussion of forms of rights does not necessarily provide inputs on the content of rights in terms of moral or legal content. Are rights moral entitlements or legal relationships? Positivists or those who take a legalist position argue that there is no relationship between law and morality. Right in terms of legal aspect means legally defined relationship between two or more persons and between the State and its citizens. It is argued that in case of any conflict between right and other claims, the former should prevail.

Dimensions or Kinds of Rights

We have discussed the concepts of positive rights (legal rights), negative rights, residual rights and fundamental rights and also rights, which are available in terms of Bill of Rights or Fundamental Rights in the Constitution. There could be various other dimensions, such as civil, economic, human, legal, moral, natural, political, social and cultural, which require the corresponding rights to be secured. These are grounds through which claims for rights can find justification. In contemporary times, it is also common to claim rights on the grounds of or on behalf of an unborn child, animals and the environment. Debate over abortion, animal protection and environmental rights are significant political debates in the contemporary times.

There are various international instruments that afford protection to various dimensions of rights, including human rights. They include the following:15

- The (UN) Universal Declaration of Human Rights [1948]

- The Convention on Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide [1948]

- The European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms [1950]

- The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination [1965]

- The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights [1966]

- The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights [1966]

- The American Convention on Human Rights [1969]

- The International Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women [1979]

- The African Charter on Human and People's Rights [Banjul Charter 1981]

These are declarations, conventions or charters that give protection to a variety of rights—civil, cultural, economic, human including moral, political and social rights. These are designed to protect a number of traditional civil and political rights. Added to these and also including some of them, are the rights mentioned in the American Declaration of Independence, 1776 and the French Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizens, 1789.

It may be useful to have a look at the kinds of rights that have been declared in the French Declaration, the UN Declaration and the Indian Constitution and also the rights identified by William Blackstone, A. V. Dicey and M. Fordham in the English Common Law. This could help us group various dimensions, such as civil, economic, human, legal, moral, natural, political, social and cultural, which require corresponding rights being secured for the individual and/or the groups.

It may be appropriate to note that consciousness about different rights for the individuals and that of the groups and demand for their recognition have been made and recognized at different occasions in history. For example, the Roman period is known for installing the Consul, the Senate and the Tribute. These three represented the respective rights and interests of the monarchical, patrician (elite and the rich) and the plebeian (lower or the common) elements. In feudal Europe, there were different groups, nobility, clergy, etc. whose rights were primary. Individual, as a concept having rights of his/her own, was neither prime nor consciously in sight. As Fernand Braudel has observed, medieval Europe was more concerned with privileges than rights.16 This meant privileges to one group or class against the interests of the other—the nobility, the vassal, the clergy, and the emerging bourgeoisie and the serfs, etc. In medieval Europe, artisans, craftsmen, merchants and occupational groups were arranged as guilds. They also reflected group's rights or privileges.

The concept of ‘Rights of Man’ or that of the individual as a conscious perspective came to the fore of debate only in post-Renaissance Europe and has continued as a staple feed for debate on rights. However, it is also recognized that claims and rights of human beings should not feasibly be based on the conceptual category of ‘individual’ only. The recognition of rights of groups will be equally important at times to preserve even the rights of the individual. For example, rights of minorities in many circumstances should be protected even to protect the basic or core human rights of the individual belonging to that category. As such, claims and recognition of rights of individuals and groups have to be appreciated in a complex dynamics of this relationship. UN Declaration on Human Rights and the provisions contained in the Fundamental Rights category in Indian Constitution recognize this aspect. Table 8.1 outlines the various dimensions and types of rights.

Table 8.1 Dimensions and Types of Rights

| Source | Rights Declared / Incorporated |

|---|---|

| French Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizen (1789)17 |

|

| UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948)18 |

|

| Indian Constitution (1949)19 |

|

| Rights in common law of England [William Blackstone, A. V. Dicey, M. Fordham]20 |

|

Briefly, various dimensions of rights may be listed as follows:

- Natural rights: Natural rights are based on natural law and individuals are entitled for them naturally. These are either inherent in individual due to natural claim or claim of moral and dignity. Thomas Hobbes and John Locke have discussed natural or inalienable rights on the basis of rights prevailing in the state of nature. Thomas Paine and Thomas Hill Green have argued for natural rights on the basis of inherent moral claim of individual. In either case, naturally available rights or rights available to human moral claim are inalienable. Some of the commonly agreed natural rights are, right to life and security (even Hobbes agreed that one can disobey the sovereign when life is threatened), liberty, property and resistance to oppression. The American Declaration of Independence [1776], the French Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizens [1789], and the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights [1948], all acknowledge natural rights as inalienable and imprescriptible. Bentham and other Utilitarian rejected natural rights as nonsense and argued for legal rights.

- Moral rights: Moral rights emanate from the very personality of the individual and are moral claims directed towards the conscience of the community or society. These tend to support individual as an end and moral agent. They are in the nature of ideal rights. In actual practice, they may or may not exist depending upon their legal recognition and enforcement. For example, Socrates, a Greek thinker, insisted on the right to speak truth, as he preached, even at the cost of drinking hemlock. Immanuel Kant, a German philosopher, felt that human beings should be treated not merely as means but as end also. Green also argued that individuals need rights for development of moral consciousness. Contemporaneously, debate over right of an unborn child or for that matter, right of a woman against rape in wedlock may be considered as examples of moral claims. Moral claims have been argued for securing legal rights; law against gender determination and abortions, laws protecting women against rape and violence in wedlock. However, Bentham was of the view that moral rights are a mistaken way of conceiving ‘legal rights that ought to exist’.21

- Human rights: Human rights can be considered as a combination of natural and moral rights. In fact, it has been argued that human rights are the most influential form of moral rights. But not all human rights come merely from moral claims. Many moral claims would be culture or community specific and could not be considered as sole foundation for human rights. In the Preamble, the UN Declaration on Human Rights [1948], spells that ‘recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.’ The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights states that ‘human rights derive from inherent dignity of human person.’22 As such, they are general rights rather than specific rights and are universal to the very existence of all human beings. Human rights are based on human personality and this is not bereft of moral claims though. But human rights also seek from natural rights in a large way and reflect fundamental inner human derive irrespective of communitarian or cultural specificity. Human right requires all human form and personality, in whatever age group, to possess the same claim of human development and personality, lest the claim for rights of unborn child would be irrelevant. It is not settled as to how are human rights different from a combination of natural and moral rights, social and economic rights, cultural rights and political and civil rights. UN Universal Declaration itself appears to include moral, natural, cultural, socio-economic, civil and political claims as basis of human rights. Incidentally, many of the claims that women's right groups insist, may appear initially as moral claims based on gender relations, e.g., against rape in wedlock vis-à-vis consent. However, they should be considered as part of human rights and accordingly women's rights with gender specificity should be treated as human rights issues. After all, the criteria of inherent dignity of human person does include the human person of a women, a child, and even an unborn child.

- Civil or social rights: Rights in person and property of an individual in relation to society or community are civil rights. It goes without saying that civil and social rights are claims based on natural, moral and human grounds. It could include rights to (i) physical freedom such as right to life, liberty and security, health and movement of body, etc. (ii) intellectual freedom such as right to conscience, thought, education, belief, religion, expression and speech and also right to freedom of association, press, etc.; and (iii) contractual freedom such as right to have contractual relations with others. Contractual freedom will encompass right to enter into contractual relations in economic and social (marital) aspects. Right to property is a significant civil right that comes under the contractual aspect and includes right to hold temporarily or on behalf of others, possess, transfer, exchange and dispose off property. Right to property is also treated as economic right. Social equality is one of the important aspects of social rights as enjoyment of rights may get affected if right to social equality is not secured. Right to social equality implies absence of distinction based on caste, race, class, colours, language, sex, religion, etc. Article 2 of the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognizes right to social equality. Indian Constitution also recognizes right to social equality and Article 17 against untouchability specifically reflects this aspect.

- Economic rights: Rights that relate to a person as a worker and his/her engagement in gainful employment come under the category of economic rights. The French Declaration provides for ‘Rights to labor, tillage, or commerce to the skill of the citizens’, the UN Universal Declaration spells right to work, free choice of employment, protection against unemployment, right to equal pay for equal work, right to form and join trade unions for protection of interest [Art. 23] and right to rest and leisure (reasonable limitation on working hours and periodic holidays), etc. [Art. 24]. There are two views on economic rights. From the provisions mentioned previously appearing in the French and UN declarations, it appears that economic rights are claims of workers and those who are employed and are having no means of production or employment. But it is also argued that economic rights includes right to contract, own and manage means of productions, etc. We can infer that economic rights could be described in two ways—one in terms of workers and employees and the other in terms of owners and managers. In fact, recognition of economic rights of the owners and managers and that of the workers and employees has evolved at two different times of history. Seventeenth and eighteenth centuries witnessed claim for recognition of economic rights of the owners and managers and got identified with early liberalism. It is only in late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries after the socialist movements and reformist liberal idea stressed the need for rights of workers that their economic rights came into picture.

- Political rights: The idea of political rights is a result of laissez-faire and liberal position, which stressed non-interference of state in individual's affairs. Early liberalism argued for rights of individual to limited government. John Locke, for example, argued for a limited representative government. Bentham advocated for one person; one vote exemplified by the utilitarian principle of each person is to count for one and no one for more than one.23 William Blackstone treated political rights as negative rights in that it is about curbing government. The claim for political rights emerged from the idea that people being the repository of supreme power, should be the electors and constituent of government. Barker, for example, has advocated that political rights instead of being treated as negative rights, as Blackstone holds, should be taken as right to constitute and control government. Thus, political rights in the form of right to vote and right to contest, get elected and occupy political offices have been stressed. Right to oppose constitutionally and peacefully; right to petition; right to form union and associations and defend political freedoms and other interests; right to hold public meetings, etc., also came to occupy the same footing. In the Indian Constitution, the right to vote is a constitutional right under Article 326 with the statutory backing in the Peoples’ Representation Act, 1951. Political rights are rights of individual as citizen. Liberal democracy advocates political right of universal suffrage, i.e., right to vote to all eligible male and female citizens. However, universal suffrage could not become a reality at least for women even in England, the mother of Parliamentary democracy, till 1919. Secondly, while political rights were very much advocated in European countries, the same however, were denied to people under colonial rules in ninteenth and first half of twentieth centuries.

- Legal rights: Legal rights have legal basis. They are a product of and protected by laws. Legal rights relate to an individual as a legal or juristic person. Theorists who support the monist view of sovereignty such as Hobbes, Bentham and Austin argue that all rights are a product of laws formulated by the sovereign. Legal rights are those, which are legally provided. For example, in India now, right to information is a legal right as it has been provided for by an Act.

- Women rights: Rights in their natural, moral, human, civil and social, economic, political and legal aspects do have relationship with women. These rights should be gender neutral and should be available to both male and female. Specifically, lack of right to vote, equal pay for equal work, equal property rights, etc. is reflection of an unequal distribution of rights. It has been argued that unequal distribution of rights due to gender bias has also resulted in women's subordination, exploitation and violence against them. As a result, demand for legal and political rights for women has been made. Feminist movements have largely been influenced by the ‘equal right’ considerations. We come across such instances where women right activists have fought for equality of rights, especially right to vote. One such instance is the Women's Rights Convention in America, which in 1848 adapted a revised Declaration of American Independence. It read, ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal.’24 Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the women's rights activist in America, was one of the vocal supporters of the ‘equal right’ movement in the mid-1840s. Women rights have also been understood in terms of securing their rights within wedlock, including rights against family violence, rights against rape and sexual abuse in wedlock. However, ‘equal right’ feminist movement has to grapple with certain religious and cultural specific issues. It has been argued that there may not be universal women rights per se. For example, a women's right to dress as she wishes may be restricted by a religious practice itself. Further, it would be difficult to find a moral or teleological argument to support or deny whether a bikini or a naqab (long veil generally worn by Muslim women in many countries) is expressive of freedom or subjugation, unless it is by choice. Similarly, many of the women rights are subject to the political system that prevails. For example, in a political system that has not allowed political rights to male, political rights to female are absent. The question, which gains importance in this context, is how to construct an ideal type of women's rights. The new direction to feminist movement came from the publication of Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique in which she advocated liberation of women from mere motherhood to full human creativity. She proclaimed abortion as woman's civil right and exhorted women to become active self-determining people. At times, radical feminists have portrayed women rights as if they are opposed to male rights. Historically, this has been due to identification of political and economic order with patriarchy, i.e., male domination. Even male-female conjugal relationships have been seen as one of domination. As a result, demand for sexual liberation from male domination has been made. Perhaps it is better to argue that women's rights should be part of human and moral rights. But given the demands for women rights being made on various grounds and against various aspects of ‘male domination’, it appears that the debate on women rights is still evolving.

- Right of self-determination or right of nationhood: Literally, self-determination stands for ability to control one's own destiny and it relates to autonomy, freewill and freedom of individual in deciding as a moral agent. In the context of organized political movement of groups, the right to self-determination means right to decide about self-rule or government or be sovereign from others. This refers to the claim of community and cultural, ethnic and linguistic groups. In the early nineteenth century, cultural, ethnic and linguistic similarity gained importance as the basis of nation-state and the basis of political organization. In fact, in the post-First World War, Woodrow Wilson advocated the doctrine of right of self-determination, as the basis of reorganizing the Austro-Hungarian, the German and the Ottoman Empires. As a result, Poland, Czechoslovakia (taken out from Austria), Serbia, Yugoslavia for Croats and Slovenes (taken out from Austria and Hungry), Estonian and Lithuania (taken out from Russia), Albania, etc., came into being. This was the first wave of operation of the doctrine of right to self-determination in Europe. In the post-Second World War, this doctrine was invoked by many nationalities to gain independence from colonial rules in Africa, Asia and Latin America. In fact, movement for creation of Bangladesh out of Pakistan can be cited as an example of operation of right to self-determination on linguistic basis. This could be termed as the second wave of operation of the doctrine of right to self-determination. After the breakdown of the erstwhile USSR and the Eastern European communist bloc, a third wave of operation of the doctrine of right to self-determination took place. A host of countries in Central Asia and the Balkans emerged out of this bloc by- and-large coinciding with their ethnic, linguistic and cultural identity with the statehood. While the doctrine garners supports from the liberals because of their commitment to the principle of self-determination and autonomy, it also got endorsement from the Marxian angle, as it was invoked in the struggle against colonial and imperial rule—imperialism being the highest stage of capitalism. However, we may add that the doctrine of right to self-determination has proved to be a double-edged sword. It has proved to be problematic in poly-ethnic and multicultural national-states.

- Environmental rights: Environmental rights refer to claims of communities or groups for protection and conservation of nature and surrounding environment (neighbouring forest areas, sources of water and water bodies, etc.) for sustainable benefit of whole of human beings or groups/communities sharing the neighbouring habitat. Sustainable benefit implies drawing benefits from nature and environment without progressive damage to it. Environmental rights have been insisted in many ways. Green movements and environmentalism are expressions of collective effort to protect, conserve and sustain nature locally and globally. These movements are also critical to the damage to nature created by industrial countries. There have been certain groups and communities that have struggled against environmental damage locally. For example, the Chipko movement in western Uttar Pradesh under the leadership of Sundarlal Bahuguna fought to save trees by adopting and protecting them from being cut or felled; the Narmada Bachao Andolan (Save Narmada River Movement) under the leadership of Baba Amte and Medha Patekar has been fighting against peoples’ displacement due construction of dams. It is generally agreed that environment presents public good and is collective heritage of all. Though the debate on relative merits and demerits of development versus damage to environment is still on, it appears that the traditional rights of people residing in natural habitats and forests to have rights to forest products, access to natural water, grassland and such accesses are getting limited due to either their displacement or damage to nature.

- Minority rights: Minority rights imply two aspects—rights of political minority and rights of social-cultural or/and religious minority. So far as conception of political minority is concerned, this is temporary and dynamic situation in democracy. Politically, majority is the operating criteria in selection of office bearers and decision-making in democracy. But majority and minority are shifting and non-permanent. Even though, at least, three thinkers and statesmen namely, Thomas Jefferson, J. S. Mill and Alex de Tocqueville expressed their concern over ‘majoritarian tyranny’. They apprehended that domination of majority would be inimical to the self-development of the individual, as those with minority opinion or view would be repressed. Jefferson, on the occasion of his inaugural address on 4 March 1801 on becoming President, emphatically spelt out the principle of minority rights on political terrain. He said, ‘All, too, will bear in mind this sacred principle, that though the will of the majority is in all cases to prevail, that will to be rightful must be reasonable; that the minority possess their equal rights, which equal law must protect, and to violate would be oppression.’25 In the field of social-cultural and or religious minority, various political instruments and charters have been provided for protecting their rights. For example, the Indian Constitution has provided certain rights to social-cultural and/or religious minorities. It may be noted that Motilal Nehru Report, 1928 has also provided for right to freedom of conscience, free profession and practice of religion, provision relating to elementary education of members of minorities. Granville Austin says that these rights were in fact called ‘Minority Rights in the early days of the Assembly and they appear in the Constitution as Rights Relating to Religion, Cultural and Educational Rights …’26

We have briefly surveyed the dimensions and kinds of rights contained in various declarations, charters and conventions. We have also discussed how various kinds of grounds are associated with claims for rights.

Theories of Rights

The concept of rights is said to have originated in the medieval period and, as Isaiah Berlin has mentioned, the notion of individual rights was absent from the legal conception of Greeks and Romans.27 Andrew Vincent corroborates this position and says that the notion of rights is comparatively recent. The concept of jus as ‘right’ in Roman Law is closer to modern concept of ‘justice’ than the concept of ‘right’ as we understand in term of social and political claims.28 In fact, as Clayton and Tomlinson have pointed out, trace of the notion of rights may be linked to natural rights.29 In contemporary times, political debate on rights occupies a central position and the debate has largely been due to different grounds that have been invoked for justification of rights. Broadly, three traditions can be identified as theoretical grounds relating to rights—Liberal—individualist position, Marxian position and Human Rights position. These theories basically focus on matters of origin, grounds of claim of rights and their nature.

Based on origin, grounds on which rights are claimed and justified, we may discuss the following theories:

- Theory of Natural Rights

- Theory of Legal Rights

- Theory of Moral-Ideal Rights

- Theory of Historical Rights

- Theory of Social-Welfare Rights

- Theory of Human Rights

- Marxian Theory of Rights

Theories based on natural rights, legal rights, idealistic rights, historical rights and social-welfare rights are generally within the liberal-individualist framework. The Marxian theory of rights invokes class nature of rights. Human rights theory may be treated as a combination of various grounds and recognizes individual and group bases of rights.

Theory of Natural Rights

Natural rights are one of the earliest grounds for claim of individual rights. Natural rights are natural claims because they are gifts of nature, product of law of nature and do not depend upon any authority or sovereign power for recognition, prescription and enforcement. Two grounds, contractual and teleological, have been identified to support the theory of natural rights.

Contractual ground implies that they carry the natural rights, which were available to individuals in the state of nature, in civil society as a result of their social contract. These rights are inalienable and cannot be separated or taken away from the individual as they are inherent and prior to society and the state. They are inviolable and cannot be changed by sovereign or the authority of the state, as they are a product of law of nature or an unchangeable cause and not created by the sovereign. The natural rights are imprescriptible as they are not prescribed and sanctioned by sovereign.

Teleological view of the natural rights looks at the final purpose, which these rights serve. This could be the purpose of moral development of human beings and their progress. Teleological or teleology stands for the ultimate cause and associates everything with a purpose and an end. It is derived from the Greek word telos, which means ‘end’.

Both contractual and teleological grounds support claims for natural rights with the help of certain overarching, final and unchangeable causes—law of nature on contractual ground and moral character of human beings on teleological ground.

Natural rights are linked with early liberalism and two of its ardent advocates, Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. They provide contractual ground to the theory of natural rights. Blackstone, Spinoza and Jefferson supported theory of natural rights. In contemporary times, Robert Nozick has employed the theory of natural rights to advance his concept of justice. Thomas Paine and Thomas Hill Green have advocated natural rights on the basis of inherent moral claim of the individual, teleological ground.

Contractual ground of natural rights: Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau

Hobbes is the earliest advocate of natural rights on the contractual ground. Macpherson regards Hobbes a theorist of natural rights because he makes political obligations dependent on his postulates of individual natural rights. For Hobbes, the state of nature is one of natural rights without any control. By portraying a state of complete or licentious liberty and natural rights of the individual, Hobbes could project two things. One, that natural rights are derived from a pre-political and pre-social condition and hence inhere in the individual and are inalienable, and second, that these rights emanate from the law of nature and are fundamental. However, due to absence of a controlling authority or sovereign, natural rights of each have impeded the natural rights of other. It is like a situation where everyone having right to have a gun and kill whomsoever one wants, ultimately becomes such that everyone fears everyone else, a situation of perpetual war.

And to constitute civil society and the commonwealth under a Leviathan, natural rights should be surrendered to this single sovereign as a result of social contract. Thereafter, the sovereign would be the sole source of rights. Hobbes requires surrender of all natural rights to sovereign, except the right to life or self-preservation. Institution of the commonwealth, powers of the Leviathan and political obligations of the subjects under Leviathan, all are based on the postulates of natural rights. He derives a doctrine of maximalist political obligation with the surrender of all natural rights to preserve primary existence, i.e., life.

Hobbes, it is said, started as individualist but ended as absolutist. This is because he based his postulates of the social contract on natural rights of individuals but ultimately ended up surrendering them to a single sovereign. However, Hobbes accepts the sanctity of natural right to life and is ready to accept violation of this a ground for revolt on the part of the subjects.

It may appear as if Hobbes seeks the end of natural rights. But it should be noted that the very basis of social contract is natural rights. In fact, right to life and self-preservation as the primary concern prompts individuals to enter into contract and institute the sovereign. This implies various rights, including right to revolt in case life is under threat. Further, Hobbes's social contract is based on the assumption that individuals have the right to contract.

It was Locke, who championed the cause of natural rights in a strong way. Locke's Two Treatises of Government contains his exposition on social contract, natural rights and government. Unlike Hobbes, Locke's state of nature is not chaotic and licentious. Wayper says, ‘the state of nature is a state in which men are equal and free to act as they think fit, within the bounds of the law of nature.’30 Individuals in the state of nature possess the natural rights of life, liberty and property. But due to absence of an established, settled or known law; a known and indifferent judge; and an executive power to enforce such decisions, there is requirement of social contract so that three organs—legislative, executive and judicial, are instituted.

By conceiving state of nature as peaceful, social and not licentious and pre-social, Locke does not require the individual to surrender their natural rights as Hobbes did. He, in fact, invokes the natural rights to support a limited constitutional government and make natural rights inalienable and inviolable in the state. Social contract results in only partial surrender of natural rights to the supreme authority. Even the supreme authority remains with the people. The rights, which are surrendered, include power of punishing others; being interpreter of natural law; its executor as well as adjudicator. Except these, individuals retain the natural rights of life, liberty and property. Natural rights provide individual exclusive and indefeasible realm, which the state cannot violate or negate. As such, government is trust of the people for protection and security of the natural rights. Unlike Hobbes, Locke provides wider scope of resistance by the people against violation of natural rights.

Right to property is an important right in Locke's formulation. An individual acquires property through labour. Interestingly, Locke's concept of property as natural right is connected with mixing of labour. Locke says, ‘the labour of his body and the work of his hands … are properly his,31 meaning thereby that whatever one creates by one's labour is his/her property. As such, individual carries property in person and goods. This means, property is in those possessions or acquisitions that individuals obtain from labour. By extension, it is also in those possessions and acquisitions that one acquires by employing other's labour by payment as contractual exchange. The principle of contractual exchange is the basis of capitalist economy. This was a sharp break from the feudal economic and political order, which was based on privileges.

By invoking the conception of natural rights, Locke provided a strong theoretical basis for a liberal-capitalist order and limited political obligation of the individuals. Locke's conception of natural rights of life, liberty and property provided basis for civil (life and liberty) and economic (property) rights, limited government, minimalist and non-interfering state, and liberal-capitalist order. Violation of natural rights can be sufficient reason for people to revolt against the government, which is a trust to protect these rights.

Rousseau's state of nature is a state of idyllic life in which ‘noble savage’ lives peacefully and happily. They have natural rights. However, natural rights should be surrendered to the will of the civil society. Rousseau gave primacy to civil liberty represented by the General Will over natural rights.

Theory of natural rights is based on the conception that there are pre-existing and inalienable rights of the individual, which are available independent of and prior to society. This theory envisages a self-contained individual with proprietorial rights on person and capacity. Macpherson in his The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism has termed it as political theory of possessive individualism. It has been argued that rights, instead of being prior to society and state, and natural, are, in fact, socially and historically determined. For example, the modern state recognizes a range of individual rights that were not available to earlier forms of state. As such, what Hobbes, Locke and Nozick argue as natural and prior rights, could only be those of a historically specific market.32 Bentham has summarily rejected natural rights as ‘simple nonsense’. The logic behind Bentham's rejection of natural rights may be the very rejection of law of nature. Bentham does not admit imprescriptible rights and natural law and advocates rights as sanction by law. Similarly, as Wayper says of Bentham, ‘His State, too, is the sole source of rights’ and ‘rights cannot be maintained against the state.’33 In this regard, Bentham stands in sharp opposition to Locke, who admits natural rights against the state. According to Bentham, neither law of nature nor natural rights could be admitted against the state.

Teleological ground of natural rights: Paine and Green

Thomas Paine and T. H. Green have sought to justify claim of prior rights of the individual, i.e., rights independent of recognition of society and the state, based on teleological grounds. This means individuals have inherent moral rights based on dignity, need for self-development and self-realization as human beings.

Paine wrote the celebrated book The Rights of Man (1791), which contained a refutation of Edmund Burke's criticisms of the Revolution in France. Paine was indicted for treason in England for this book, as he had supported the French Revolution and appealed for overthrow of the British monarchy.34 Paine advocated overthrow of English monarchy because he thought the rights of man could be better secured by a republican constitution than by English government under monarchy.

Though Paine supported natural and prior ‘rights of man’ he was opposed to the doctrine of social contract. He thought this amounted to some type of permanent binding on all generations and would impede progress. Instead, Paine sought to build theory of natural rights on the basis that they are ‘pre-existing in the individual’, that is to say, the rights of man are inherent in the very personality of the individual; almost like present day insistence on human rights. The individual carries these rights in the civil society as part of inherent rights of personality for which social contract is not required. In The Rights of Man, Paine says, ‘the end of all political associations is the preservation of the rights of man, which rights are liberty, property, and security … the right of property being secured and inviolable, no one ought to be deprived of it …’35 We can see that both Paine and Locke list similar natural rights, i.e., rights of life (security), liberty and property. Though, Locke invokes a contractual basis for admitting the inviolability of these rights in the civil society and by the state, Paine argues on the basis of inherent rights of individual personality.

T. H. Green, a supporter of positive liberty, a provides the basis for reformist liberalism and welfare state. He ‘revised the conception of the individual; and in particular . individualist account of how individuals come to have rights.’36 Locke's Liberalism supported conception of an indiividual who is self-contained, atomist and a carrier of natural rights. Green's liberalism invoked conception of an individual as carrier of natural rights because these rights are prior to society and not because he is an atomist or self-contained. Green stressed that rights of an individual have meaning because individuals are to be seen as social beings and bound by common good for enjoying rights. Freedom for him, ‘is a positive power or capacity of doing or enjoying something worth doing or enjoying and that too, something we do or enjoy in common with others.’ If so, then recognition of this freedom cannot be admitted or sustained on the conception of Lockean premise of an individual who is self-contained, atomist and a carrier of natural rights. Green's individual is socially and ethically related to a ‘larger common good’, to use Tony Walton's phrase, for enjoying freedom.

Green views the rights of human beings tied up with two things—one, with moral character of individual-self and second, with common good. Moral character and common good provide bases of individual rights. And if moral character is linked with positive power or capacity, it requires realizing this ‘in common with others.’ Individual rights are dependent on social recognition but that recognition emanates from moral consciousness of the community, which is common good. According to Tony Walton, ‘For Green, rights could not be explained in terms of an individual's ‘natural’ freedom … or pre-social individual autonomy, … On he contrary, the extent of a person's rights is sanctioned and recognized by the common good which is their source and foundation.’37

Implications of Green's conception of individual rights as embedded in social recognition based on moral claim are: (i) rights should be enjoyed in common with others and not as atomistic and a self-contained person that Lockean liberalism advocates, (ii) common good being source and foundation of rights, requires that basic resources of society should be equally available to all for enjoying the positive power or capacity by each individual, (iii) while Lockean conception of natural rights admits inalienable and prior rights vis-à-vis society and state and Hobbes's and Bentham's conception of rights ground rights in the recognition of the state and the sovereign, Green grounds rights in the moral character of an individual and recognition of the community which he calls ‘Natural Rights’, (iv) while Locke's conception requires noninterference by the state in operation of the rights of life, liberty and property, Green's conception of rights entails state's pursuing common good for realization of rights.

Natural rights and contemporary debate: Rawls and Nozick

Two contemporary theorists, John Rawls (A Theory of Justice) and Robert Nozick (Anarchy, State and Utopia), have based their formulations of rights of individual and justice on social contract and natural rights, respectively. Rawls has used the idea of deriving rights from social contract to present his views of an equalitarian social order. He takes the example of hypothetical individuals who are unaware of what sort of individuals they are (selfish and self-contained or social; competitive or cooperative; possessive or sacrificing) or what position in society they would occupy. Then Rawls says, ‘if these hypothetical individuals were devising a structure for future society … would agree that each person should have equal right to the most extensive total system of equal basic rights which are compatible with a similar system of liberty for all.’38 Rawls seeks to argue that when individuals enter into a social contract, the rights that would emerge from it would be based on the principle, which protects the individual from the oppressive effects of others. And these would include, as Clayton and Tomlinson say, ‘conventional civil liberties such as freedom of speech, freedom from arbitrary arrest, freedom of conscience and freedom to hold private property’. Incidentally, these are also the rights that natural right theorist advocates, right to life or security, liberty and property.

Drawing from Locke's inviolable property rights, Robert Nozick has developed the concept of prior and inalienable individual rights. On this basis, Nozick attacks the concept of equalitarian justice and welfare state. He contends that individual rights have priority over other principles, such as equality. Based on inviolable property rights, Nozick seeks to develop an entitlement theory of people's natural assets in the sense that people are entitled to the fruit of their assets or skills and to use them to their advantage.39 For example, he argues that a doctor is entitled to his/her skill and should not be robbed of the fruit of entitlement. He rejects the argument that health being a fundamental service should not be subject to selling and purchase and should require regulation of doctors, as he would treat skills not as common assets. Nozick's contention that liberty is incompatible with and has priority over equality and every individual has exclusive rights in him and no rights in anyone else (entitlement theory), means every individual has inviolable right to liberty and property. As Clayton and Tomlinson point out, for Nozick ‘rights are ‘side constraints’ which place moral limits on goals which may be pursued by us in the sense that whatever we do, we must not violate the rights of other’.40 Thus, entitlement theory means everyone has exclusive right in himself/herself and in no one else. Implication of this way of looking at rights is that no one should be directed to pursue a goal that violates the exclusive right, e.g. the doctors directed to use their skill for others by regulation.

Critical evaluation