11

Concepts and Theories of Democracy

Introduction

For many, democracy is a guarantee of freedom, equality and popular rule. But for some, it is the rule of the ignorant and the average person in which number counts, not merit.1

Democracy is understood in a variety of ways. The Athenians in ancient Greece led by Pericles celebrated democracy, Plato rejected it as the rule of the ignorant and Aristotle found it as a corrupt form of polity, his balanced constitution. By the time Abraham Lincoln ended his famous Gettysburg speech on Nov. 17, 1863 in the mist of American Civil War commotions; in his last sentence he had already given both flesh and spirit to the meaning of democracy as government of the people, by the people, for the people. David Held in his Models of Democracy says that ‘the history of the idea of democracy is curious; the history of democracies is puzzling.’2 Let us get a flavour of this puzzle.

The concept of democracy originated in the Greek demokratia, meaning demos (the many or the people) and kratos (power or rule).3 It is apparent that the rule of the many or the people was in contrast to the rule of the few (aristocracy) or the rule of one (monarchy). For the Greeks, and for Plato and Aristotle, democracy was one of the forms of government or constitution and was part of the cyclical alteration. For both, democracy like aristocracy and monarchy in addition to being a form of government or constitution also represented certain principles and values. Aristotle found that democracy implied spirit of political equality and distributive principle based on free birth. A democratic constitution involved distribution of public offices and rewards based not on high birth, wealth or high education, but on free birth and rule of the people. In the classical sense, democracy is considered a form of government in which the many or the people ruled, and which distributed political offices based on equality and free birth.

Classical democracy is generally identified with the democratic set up that prevailed in Athens in ancient Greece. Classical democracy generally has two main features. Firstly, it was rule of the many or the people; and secondly, it was practiced directly, i.e., people participated in person in the day-to-day operation of the political affairs and public office. Direct participation is still found in many Swiss cantons and some of the states in USA. However, in these cases, direct participation is in the form of legislation or making of law through initiative (legislation is proposed by the people instead of elected members), referendum and plebiscite (direct voting on certain issues of public importance either for making law or deciding the issue) and in the form of control on the elected representatives through recall (elected members are called back, removed by the people mid-way unlike the practice of fixed terms in our democracy). This is called direct or participatory democracy. In classical sense, democracy means a form of government directly participated by the people in policy and legislation-making.

However, by the time democracy journeyed to the modern world, the people became sufficiently large and the government adequately complex. Direct participation became impractical and affairs of the government technically demanding. By seventeenth century in Europe, absolutist monarchies were giving way to popular governments and by the close of eighteenth century the trio of Revolutions - the English (1688), the American (1776) and the French (1789), heralded the modern era of representative democratic rule. The political ideas of social contract and consent (Locke and Rousseau) rights of the individual (Locke and Paine) and representation gave philosophical and political bases to representative democracy.

Meanwhile, representative democracy required defining two things, one, who would be representatives, and two, who would choose the representatives. Apparently, the people or the general citizenry is to be the choosers and from amongst them, who so ever command their confidence and consent, the representatives. This, in turn, means giving political rights to the people for choosing. As such, democracy as a form of government came to become representative, i.e., rule by the representative delegates of the people. A group of elected representatives and not the people per se runs the affairs of the government. This is indirect or representative democracy, which we find in many countries in the contemporary times, including India. In classical sense, democracy has two forms of government, one, direct or participatory democracy and the other, indirect or representative democracy.

Subsequently, democracy has acquired various forms and has been interpreted and understood differently. Fundamentally, the concept of democracy means distribution of power in society and its implication for political power. This is to say who wields power and how it is reflected in the political set up. Liberal approach views power distribution in society as one of dispersion and distribution in such a manner that individuals and groups enjoy power and they influence the exercise of political power. Pluralist approach, a sub-set of liberal approach, assumes that society has various groups, which act as power centres and influence exercise of political power. There is an elitist approach that upholds that power distribution in society is in favour of a small minority of the people. The basic assumption of the elitist approach is that democracy as a government is a rule of elite minority and not of the people. In contrast to all these, the Marxian approach denies any possibility of democracy in a capitalist society and argues for socialist democracy. Democracy is a capitalist set is a class rule, rule of the owners over the labourers.

Meaning and Definition of Democracy

In classic sense, democracy means the rule of the people, either directly or through elected representatives. Cleon, the Athenian politician and general who was killed during the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) defined democracy as ‘that shall be democratic which shall be of the people, by the people, for the people.’4 This was the definition, which Lincoln used in his Gettysburg speech on 19 November 1863. For the Greeks and the Athenians in particular, democracy was rule by the majority as compared with the few elites ruling as oligarchy. In this meaning, democracy is taken not only as rule of the majority but also involving the spirit of equality. Subsequently, even representative form of democracy also recognises the principle of equality. However, this equality is mainly confined to political equality where equal voting right and right to hold public offices are treated relevant. In this sense, people are treated as the source of legitimate power. Democracy as the rule of the people can be direct/participatory or indirect/representative.

Democracy is also widely described as a process of selecting governments. This implies free and fair elections under open, multi-party electoral competition and based on universal adult suffrage. A government selected as such is treated as democratic government. Samuel P. Huntington, a political theorist who is known for his Clash of Civilizations thesis, says that ‘elections, open, free and fair, are essence of democracy.’5 In this democracy is about open, fair, free and competitive election process for selecting government. However, in this sense, it is confined to producing leaders and it has nothing to do if this democratically elected government becomes irresponsible, work against public interests is corrupt and is run for selfish motives of the small clique or elite minority.

A third meaning given to democracy combines both the notions mentioned above. It is treated as a form of government. Democracy as a form of government implies two aspects: (i) who share power in government, and (ii) how are those who govern and legislate, acquire their office? In this sense, democracy conceives that people, either directly or through their representatives, shares power in government. The representatives exercise legitimate power on behalf of the people. Secondly, those who actually govern and legislate acquire their office through popularly held open, free and fair competitive elections based on universal adult suffrage.

J. S. Mill in his Considerations on Representative Government (1861) has mentioned two different aspects that go in the name of democracy. He defines ‘pure idea of democracy’ as ‘the government of the whole people by the whole people, equally represented’. Mills contrasts this idea of pure democracy with commonly conceived and practised idea of democracy as ‘the government of the whole people by a mere majority of the people, exclusively represented.’6 While the former means equality of all citizens, the latter though confounded with the first, is government of the privileged, in favour of numerical majority. According to Mill, in pure democracy, everyone shares in power by equal representation. In the other sense, democracy as a form of government though called government of the whole people is only government of the majority. This majority actually elects representatives. Mill's contention is that in representative democracy since representatives are elected on the basis of majority vote, they cannot by definition represent the minority. Lincoln's definition of democracy as ‘government of the people, by the people, for the people’ explains the aspects involved in democracy as form of government. Government of the people means people directly or indirectly ruling; government by the people means direct rule of the people and government for the people means government in favour of and in the interest of the people whether the people are ruling directly or through representatives.

The notion that democracy is a form government is widely held and has been supported by a host of writers. They include, amongst others, Alexis de Tocqueville (Democracy in America, 1835–40 & The Old Regime and the French Revolution, 1856), J. R. Seeley (Introduction to Political Science, 1896), A. V. Dicey (Law and Opinion in England, 1905), James Bryce (Modern Democracies, 1921) and A. B. Hall (Popular Government, 1921). A. V. Dicey treats democracy as a form of government in which ‘the governing body is comparatively large fraction of the entire nation’. James Bryce in his Modern Democracies (1921) has compared what he says, ‘Six Democratic Governments’, namely Australia, Canada, France, New Zealand, Switzerland and the United States with other forms of government, namely Monarchy and Oligarchy.7 For Bryce, democracy is ‘that form of government in which the ruling power of a state is largely vested, not in any particular class or classes, but in the members of the community as a whole.’8 Lowell says democracy is an ‘experiment in government’ and for Seeley it is ‘a government in which everyone has a share’. Hall defines popular government as ‘that form of political organization in which public opinion has control.’9

All the definitions cited above make it clear that generally a majority of the people, shares power and influences government policy and legislation. However, some of the definitions, for example, by Seeley points towards a pure form of democracy in which every person has a share. Such a definition is exclusive definition and is not based on practical cases, as there has been no such government where everybody has share. The essence of Seeley's definition could be to point towards such an arrangement of democracy as a form of government, where even minority could share power. In fact, this is what exactly Mill says. Mill seeks to remove the defect of democracy resulting from majority principle and suggests both plural and proportional representation to deal with this weakness.

Alexis de Tocqueville treated democracy both as a ‘form of government’ and a ‘type of society’.10 He describes democracy as a form of government by designating it as a regime in which ‘the people more or less participate in their government’. On the other hand, he used democracy to describe ‘democratic institutions’ or ‘democratic way of life’. He mentioned about passion for social equality in development of democratic societies. Tocqueville was of the view that all major revolutions have their purpose destruction of inequality. Democracy based on the principle of social equality is immune from revolutionary disturbances and serves as a training school for citizenship. However, he cautioned that passion for equality might be inimical to individual liberty. This way of understanding democracy as helpful to citizenry in educating and uplifting their intelligence was also the main argument of J. S. Mill. Mill felt that democratic participation and free and open discussion help people elevate their character and political intelligence. C. B. Macpherson (The Life and Times of Liberal Democracy) and David Held (Models of Democracy) have analysed Mill's justification of developmental democracy in which development of personal qualities, moral and intellectual standards of the people become possible. Democracy is seen as having an intrinsic or value in itself; value is the opportunity that it gives for personal, moral and intellectual development.

James Russell Lowell (Democracy and Other Essays) considers democracy as a social system or a ‘form of society’ as Tocqueville thought. It is a form of society in which ‘every man (should include woman) has a chance and knows he (she) has it.’ Lowell conceives democracy in the same tradition as Tocqueville did where equal chance is available to all.

According to Andrew Vincent, Benjamin Constant in France, Jeremy Bentham and James Mill in England and James Madison in America ‘wanted to use democracy as an instrumental device to prevent dominance of any one group, whether the masses or aristocracy’.11 Bentham conceived democracy as a protective mechanism, which should provide protection from dominance and arbitrary act of government and group of citizenry against each other. Unlike Mill's developmental idea of democracy as intrinsic good or something which has value of its own for intellectual and personal advancement of individuals, Bentham views democracy as an instrument for protecting citizens. James Madison argued that checks and balances are required to provide defence against tyranny. Madison was providing defence against dominance of any one group as Tocqueville or Mill did. Madison's system of checks and balances is called ‘Madisonian system’.12 The system of checks and balances are also present in Indian democracy where legislature, executive and judiciary work as checks on each other.

Brief analysis given above suggests that democracy can be viewed as either or a combination of the following:

- As a political concept of power sharing, form of government, device to control dominance and mechanism for selecting rulers;

- As a social value or social condition or type of society where value of social equality and equal chances prevails and democratic institutions obtain;

- As an ethical principle with its own intrinsic value for the moral, intellectual and self development on citizens.

Professor F. Giddings (Democracy and Empire, 1900) treated democracy in all the three meanings given above. He treats democracy as a form of government, a form of state, a form of society, or combination of all the three.13

In early twentieth century, Professor Laski and the guild socialists, Sydney and Beatrice Webb, G. D. H. Cole and others advocated industrial democracy. Industrial democracy implied worker's participation in industrial and economic activities. Democracy is now used in all three dimensions - economic or industrial democracy, political democracy and social democracy.

Issues of social democracy have been part of various civil rights and liberation movements. Feminist groups and civil rights activists have advocated that primacy should be given to social democracy. Social democracy implies socio-economic equality as the basis of political process and power sharing in government. Some of the extreme examples of socially undemocratic practices have been slavery in many parts of the world, apartheid in South Africa, discrimination against women everywhere and caste untouchability in India. Social democracy means absence of unreasonable, illogical, irrational and anti-human discriminatory practices that hampers individual initiatives, restricts free participation in the processes of civil society and political system, excludes and marginalized people by invoking artificial and constructed reasons. One of the important social and civil right activists of modern India, Bhimrao Ambedkar unequivocally declared social democracy in India as a prerequisite for political democracy to succeed. He felt that the political democracy and universal adult suffrage provided by the Constitution of India would be meaningless unless conditions of social equality are provided and strengthened for all castes.

As such, democracy is not a mere form of government or form of the state; rather it is also a condition of society. Democratic social process was identified by Tocqueville as a social movement, insisted by Ambedkar as pre-requisite for political democracy to succeed. In ninety sixties and seventies, radical democrats insisted on socio-economic equality as a precondition for success of political democracy. Democracy is a theory of government as much as it is a theory of society. A democratic government means a government elected by a process of free, fair and open election based on universal adult suffrage and within a competitive multi-party situation. A democratic society means a society with socio-economic equality and a democratic state would be one in which the community gets a chance to participate in the open and fair political process and the government work in the interest of the community. Canadian political sociologist, R. M. MacIver, in his The Modern State (1926) defines democratic states as ‘those in which the general will is inclusive of the community as a whole or of at least the greater portion of the community, and is the conscious, direct, and active support of the form of government.’14

Forms of Democracy

Before we discuss the various theories of democracy, let us see how has the term democracy been characterised by different adjectives. A variety of names, adjectives and ornamentations are associated with term democracy. This is due to classification and grouping of democracy differently either due to different theoretical perspective or self-styled leadership and elite donning the cap of democracy to legitimise their regimes.

Bourgeois or Capitalist Democracy

Marx, Engels and Lenin and subsequently, Gramsci, Miliband, Poulantzas and Althusser apply this terminology to designate the operation of democracy in the context of liberal and capitalist economy. Democracy as a form of government is treated as class government dominated by the capitalist or the bourgeoisie. It is an arm of exploitation of the workers and to be replaced by the dictatorship of the proletariat or the people's democracy.

Classical Democracy

This is characterised by the democratic tradition, which considers ‘rule of the people’ as the basis of democratic participation. ‘Rule of the people’ may obtain through direct or indirect participation. This includes direct democracy of Athenian type and indirect democracy of liberal variety as they obtain in Anglo-American and many developing countries.

Democratic Centralism

Indirect form of democratic selection and nomination of leadership and public officials is mainly identified with Lenin's concept of democratic centralism. It involves election and nomination of party and public officials from below in a pyramidal structure of party formation, i.e., democratic election and nomination of officials and leadership. However, decisions, orders and policies flow from above downward for implementation, i.e., centralism. Democratic centralism is unique feature of Socialist-Communist party organisations. However, in its pure form, it does not carry multi-partyism or involvement of groups.

Direct Democracy

Classical form of democracy that involves direct participation and/or means of direct intervention by citizens in legislation and accountability of government such as recall, initiative and referendum. It prevailed in Athens and presently prevails partially in Switzerland and some states of USA. This form of democracy has its supporters in Pericles in Athens and Rousseau and Mill during the eighteenth and ninteenth centuries, New Left and presently, the Radical Democrats such as Macpherson, Pateman and Bottomore.

Illiberal Democracy

As a form of government practiced in many developing countries which combines democratic means of election of representatives, reaffirmation of leadership and public offices but negates the liberal tenets of civil rights and individual liberty. They are democratically elected or nominated elite or leaders but do not allow limited and constitutionally accountable government. Fareed Zakaria in his The Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and Abroad (2003) has called such democratic practices, illiberal democracy.

Indirect or Representative Democracy

A classical form of democracy identified with representative form, which implies indirect policy and legislation making. In this participation of the people is indirect through their representatives elected periodically based elections. Liberal democracy as it prevails in Anglo-American countries and many developing countries such as India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Turkey is known as indirect democracy. All representative governments are indirect democracies.

Industrial Democracy

Some thinkers and observers such as Prof. Harold Laski advocated industrial democracy, which involves worker's participation in industry. It is application of the concept of democracy in industry.

Liberal Democracy

Government based on a combination of democratic values (open, free and fair periodically held elections based on universal suffrage) and liberal-constitutional values (liberty and rights of individuals, checks and limitations on government). Main principles are representative government, open and free elections, adult suffrage, majority principles as decision-making criteria, checks and balances between different branches of power, individual rights and liberties and a limited and accountable government. Liberal democracy is the desired form of government that prevails in almost all capitalist-industrial societies and in many welfare economies such as India. John Locke, James Mill, Jeremy Bentham, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, Tom Paine, John Stuart Mill, William Blackstone, A V Dicey, James Bryce, Ivor Jennings, Dadabhai Naoroji, Mohd. Ali Jinnah, B R Ambedkar, J L Nehru, Friedrich Hayek, Robert Nozick, Francis Fukuyama, and host of writers, theorists, practitioners and observers have advocated, upheld and supported liberal democracy. Indian constitution enshrines liberal democratic tenets. Fundamental rights, adult suffrage, elections and representative government with separation of powers make Indian democracy liberal democracy.

Madisonian Democracy

American leader, James Madison was very concerned with protecting individuals and groups from the arbitrary power of government. He insisted on limiting government power and conduct through well-laid mechanism of checks and balances. Separation of powers of different organs of the government such as legislature, executive and judiciary with each having check on the other, is considered a form of limitation on the power of the state. Madison's focus is reflected in American democratic institutions. American liberal democracy is reflection of Montesquieu and Madison's emphasis on checks and balances. It is a limited, liberal democratic government.

Participatory Democracy

A form of direct democracy associated with two dimensions of participation. Firstly, direct and unmediated participation of the people in government and legislation is considered as the basis of democracy. Athens and Plebeian Romans practiced it and Jean Jacques Rousseau in his The Social Contract advocated this form. J. S. Mill in his Considerations on Representative Government supports ‘a pure idea of democracy’ which he defines as ‘government of the whole people by the whole people, equally represented’.15 This means even if citizens do not participate directly, it must represent everyone and not only the majority. Secondly, radical democrats and New Left have emphasised that participatory democracy means participation of the people as individuals, groups and social movements. This requires two things: one, reduction of socioeconomic equality, and second, change in the image of human beings from mere consumers to exerters of rights and developers of capacities. Macpherson has insisted these two aspects as prerequisite for meaningful participatory democracy.

Party-based Democracy

Representative democracy is mediated through parties and party-based designations are applied to democracy. There can be bi-party or multi-party democracy. Generally, multi-party democracy is considered a positive sign of democratic competition, though America has a stabilised two-party democracy. The UK though has two main parties, Conservatives and Labour, it has other parties also such as the Liberals. India, Italy, France, Germany, etc. are examples of multi-party democracy. In fact, France, Germany, Italy and after 1990s India have witnessed intense multiparty competition resulting in coalition governments. In such a situation, intense multi-party competition has resulted in coalition democracy and to some extent governmental instability.

People's Democracy

People's democracy is practiced in socialist regimes called people's republics, e.g., People's Republic of China, People's Republic of North Korea, etc. Based on the organisation of communist or socialist party and Lenin's democratic centralism, people's democracy is based on elected deputies from amongst the party leaders and workers. Generally, it does allow multi-partyism because as the nomenclature sounds, people's representation cannot be fragmented, as there is no class distinction. There is no need for multiple parties as there is no contradiction in the interest of the people in the form of class. Marx's and Lenin's concept of dictatorship of the proletariat after the revolution however, may not be a full people's democracy.

Plebiscitary Democracy

It comes from the practice of direct participation of the Roman plebeians in assembly to legislate. It is a form of direct democracy. However, many writers and observers have designated plebiscitary democracy those regimes that use mobilisational strategy to get affirmation to their policies, offices and legislation. Here, participation of the people is coercively managed, e.g., affirmation of office by one-person ruling over an extended period. According to this form, Hitler's mobilisation and referendum can be termed as plebiscitary and so could be Saddam Hussein's in Iraq when he ruled and Muammar Al-Qadafi's in Libya or Fidel Castro's in Cuba.

Popular Democracy

Popular democracy is direct democracy, unmediated and participatory, popular self-government. Rousseau conceptualised such form of government. Legitimacy of the government flows from citizen's determining their legislation and policy in their direct assembly. It presupposes a ‘general will’ or a collective will of the community without any factional or sectional division. It is said that Julius Nyerere in Tanzania through his concept of ujamaa (that insist on consensus and prohibits factionalism) sought Rousseau-type popular democracy, though not with direct participation.

Representational Democracy

Like representative democracy, representational democracy is indirect democracy. Observers use this to designate a form of democracy in which ‘decision making processes reflect inputs from a broad range of social groups’. Consociational democracy as conceptualised by Apter and Lijphart and Polyarchy formulated by Dahl would fall under this category. It is not based on majority principle of representation; rather it advocates a broad range of participation of interests in governmental process.

Westminster-type Democracy

Westminster is the area in London in which British parliament is located. Liberal democracy originating from the British parliamentary practice is known as Westminster type democracy. In addition to liberal democratic features, its features may include ceremonial head of the state (monarch or president) with real head of government (prime minister). Beside England, Australia, Bangladesh, Canada, India, New Zealand, etc. follow this type of democracy.

It appears democracy is a desired and sought after concept. Possibly, this is because adding ‘democracy’ with whatever regime one operates, gives some sort of legitimacy and both domestic and international acceptability. A democrat may wonder how in the process of legitimising regimes, democracy itself is being sacrificed.

Classical Democracy: Participatory and Representative Democracy

In classical sense, democracy is understood both as direct and indirect democracy. Direct or participatory democracy was found in ancient Athens, Greece where people participated directly in the political affairs of the polis. In contemporary times, direct democracies are found in Swiss cantons and American states. Direct democracy means participation of the people or eligible citizens in the affairs of the state or community. It implies no or partial delegation of power or responsibilities and duties to elected or nominated candidates.

Direct or participatory democracy

Direct participation of the eligible citizens in direct democracy has two aspects. One form is found in Athenian model where direct participation was in the form of physical presence of the eligible people in the assembly. A second model is found in Swiss cantons and American states. The later is characterised by certain popular methods of democratic participation and legislation. These methods include the practices of initiative, recall, plebiscite and referendum. The practice of initiative seeks ‘to place in the hands of the people a direct power of initiating or proposing legislation which must be taken up by the legislature.’16 Practice of initiative allows people to initiate proposals or submit issues and subjects, which require legislation and formulation of laws or acts or amendment to the constitution and existing laws and acts. The practice of recall is a check on the performance of the delegates and gives dissatisfied electors the right to recall their representatives even before the term of office is completed. It means a representative may be recalled from the legislature and replaced by another one as per the will of the people. Referendum is a practice of referring a law or a specific subject of importance to the whole body of electorates or citizens for their approval or disapproval. Referendum is also known as plebiscite. Both referendum and plebiscite were popular Latin practice. Referendum literally meant something to be referred to the Senate of Rome and plebiscite meant a law enacted by the plebeians or ordinary citizens of Rome gathered in assembly. According to C. F. Strong, referendum and plebiscite refer to the same practice.17 However, at times, a distinction is made between matters of constitutional importance and of political importance and referendum is related to the first while plebiscite is for the second. Ambitious rulers such as Napoleon I and later on, Hitler used plebiscite to secure popular approval to their political actions and circumvent the existing governmental machinery. In India, certain separatist groups have been advocating holding of plebiscite on the issue of separation of certain parts from India. However, it can be argued that when democratic process of negotiation, representation and influencing Government's policy is already available, is there a need for a separate mechanism of confirmation through plebiscite?

In present days, referendum or plebiscite has been used in Europe to secure citizens approval on issues such as European Monetary Union, etc. Swiss cantons and the American states use these methods of direct democracy and popular checks. Referendum is being used in the Palestinian Authority to determine issues of political and constitutional importance. Generally, a referendum is worded to invoke answer in ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. ‘For example, ‘Do you agree to the merger of area X with Y’; or ‘Do you agree to X joining the European Monetary Union’, or ‘Do you agree to Y joining the WTO’..

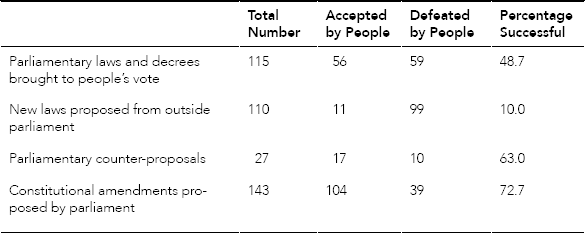

All the twenty-six Swiss cantons (20 full and 6 half cantons) use referendum for approval of laws and constitutional amendments proposed by the parliament. An analysis of Swiss referendums between 1866–1993 by David Butler and Austin Ranney (Ed) in Referendums around the World, suggests that not all those that parliament proposes get approved by the people (see Table 11.1).

Table 11.1 Outcomes of Swiss Referendums, 1866–199318

One obvious conclusion is that if parliament and representatives alone had been the final authority for legislation, it would not have represented at least interests of the people ranging from 27 per cent to 51 per cent in different cases. However, defiance does not mean what Beedham says, ‘direct democracy spells chaos for Switzerland. In return for the parliament's acceptance that the people are the boss, the people are quite often willing to heed the parliament's views.’19

The idea of democracy is based on the assumption that every eligible citizen (voter) is entitled to have equal say in the conduct of public affairs and all are entitled to an equal voice in deciding how they should be governed. If this is the case, then why this voice should be heard only after four or five or even seven years. What happens to that supreme power of the people during the interval between two elections? If Swiss experience is a pointer, it appears some of the legislation may not have people's consent, though the representatives enact them. A democracy in which we rise up periodically to feel powerful is what Beedham says, ‘part-time democracy’. For the rest of the period, we either nod our heads in approval and engage in debate or grow frustrated and apathetic. This echoes Rousseau, who was critical of representative democracy on the logic that General Will cannot be represented and that too only periodically.

Rousseau a supporter of popular sovereignty provided a philosophical basis for direct democracy. Lincoln's Gettysburg speech spelt the spirit of both direct and indirect democracies. Lincoln had said, ‘… that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom - and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.’20 According to Andrew Heywood, Lincoln's idea of ‘government by the people’ and ‘government for the people’ contains ‘two contrasting notions of democracy.’21 While government by the people stands for direct participation of the people in government and is equal to ‘popular self-government’, government for the people connotes government that serves public interests whether people themselves rule directly or not. Representative democracy assumes the second meaning and seeks to establish a form of government that benefits the people.

In contrast to the direct democracy, indirect or representative democracy is based on the delegated participation. This means instead of people participating directly in person, elected representatives participates in legislation and decision-making and in day-to-day political and policy affairs on behalf of the people. In indirect democracy, electorates get to elect their representatives periodically (at intervals of four, five or seven years) who represent the wishes and wills of the people during the terms of their office.

We can identify direct democracy with plebiscitory legislation and indirect democracy with filtered legislation. In the former, people express their wishes and wills directly, in the latter, wishes and wills of the people are filtered through the intelligence and wisdom of the representatives. Advocates of representative democracy argue that filtering of legislative enactments through the intelligence of representatives becomes necessary in the face of growing complexity of governmental activities, size of the population and technical nature of legislation in a welfare state. In fact, it has been observed that even representatives have now been faced with the problem of paucity of time and energy to devote time for entire legislative activities. A phenomenon called delegated or subordinate legislation has been on rise through which the elected members enact the broad requirements of legislation and leave the details to be completed by specialised and technical committees or officials. This means not the whole of legislation has the advantage of being filtered through the wisdom and intelligence of the representatives. Further, with growing level of awareness and educational qualification, the electorate can also boast of equalling the wisdom of the representatives. However, the factor of unmanageability of the electorate in direct manner may be an issue against direct democracy.

Beedham in his Survey on Full democracy published in The Economist in December 1996 has opined that the changes that have taken place between the ninetheenth and the twenty-first centuries ‘have removed many of the differences between ordinary people and their representatives. They have also helped the people discover that the representatives are not especially competent. As a result, what worked reasonably well in the ninetheenth century will not work in the the twenty-first century. Our children may find direct democracy more efficient, as well as more democratic, than the representative sort.’22 Based on Beedham's prediction, we can say that democracy, as ‘government by the people’ is still an unfinished agenda that may grow to its full heights in the twenty-first century. Compared with Francis Fukuyama's declaration of triumph of liberal democracy after collapse of communist ideology, it is obvious that liberal democracy may have triumphed over the nazi, the fascist and the communist forms of government in the twentieth century; it has still to struggle with the very concept of democracy in the twenty-first century. Probably, representative democracy may need to incorporate certain means of popular checks as referendum, recall and initiative to make it more democratic.

There is already a growing awareness and interest in participation of the people in the political affairs. In 1960s and 1970s, a host of activists and thinkers argued in favour of participatory democracy. This is also known as radical democracy and has been supported by New Left thinkers. They include C. B. Macpherson, T. B. Bottomore and Carole Pateman. They suggest that in liberal democracy, liberal values dominate and tilt towards requirements of capitalism. This means that values of democracy get belittled. In such a condition, democracy as a participatory and developmental mechanism does not help people in their advancement. As in J S Mill, the radical democrats conceive democracy as a mechanism of moral and self-development through participation, discussion and debates that shape citizens identities and interests. In his book, The Life and Times of Liberal Democracy (1977), Macpherson has discussed about ‘participatory democracy’ implying ‘substantial citizen participation in government decision making’.23 According to Macpherson liberal-democratic government can be made participatory if people do not participate in democratic process/elections as mere consumers but act as exerters and enjoyers of development of their own capacities and there is substantial reduction in social and economic inequality. Possibilities of democratic power sharing and direct and immediate means of political action can make possible a more continuous practical participation by large number of citizens in determining the quality of their lives. People's actions and civil society initiatives that have brought awareness and have resulted in the Right to Information (RTI) Act in India fall under this category. India has also adopted Panchayati raj system which is grass root direct democratic set up and allows direct participation of village panchayat is local level decision making.

It seems the challenges to representative democracy in twenty-first century are two-fold. Firstly, it should shed some of the unnecessary representative flab and be more popular with democratic means of participation such as referendum, recall and initiative, as Beedham suggests. Secondly, it must become participatory in the developmental sense to realise the liberal goal of equal liberty through reduction of social and economic inequality, as the liberal democrats suggest. Table 11.2 lists the features of participatory and representative democracies.

Table 11.2 Features of Participatory and Representative Democracies24

| Features | Participatory Democracy | Representative Democracy |

|---|---|---|

| Justification for democracy |

|

|

| Nature of sovereign power |

|

|

| Who are the participants/ electors |

|

|

| Mode of participation |

|

|

| Policy and legislation-making |

|

|

| Mode of acountability of public officials/ representatives |

|

|

| How to differentiate the citizens and holders of public offices |

|

|

| Condition where prevails |

|

|

| Merit |

|

|

| Demerit |

|

|

Liberal Democracy

Government of the people?

Indirect or representative democracy has generally operated within the context of liberal democracy. This means democracy is qualified by values and principles of liberalism. One may argue that in this, ‘liberal’ may dominate over the ‘democratic’. This is the charge, radical democrats make against liberal democracy. It further leads to the doubt: whether problems of democracy are, in fact, problems of liberalism.

Indirect or representative democracy was philosophically legitimised by the concepts of social contract, natural rights and consent of the people. In Locke, government becomes a trust of the people while the latter retains political supremacy. Government is representative of the people to protect the natural rights and is limited by this scope. As such, government must be representative of the people, their rights and based on their consent.

Liberal democracy combines liberal and democratic elements. Liberalism is based on the notion of individual liberty and to this end, a limited state and authority. Authority should not interfere with the activities and conducts of individuals. Scope of liberty is defined as coterminous with absence of interference from the authority and the state. Liberal elements in liberal democracy include:

- Principle of individual liberty and natural and inherent rights are given primacy. This results in charter of liberties and rights of the individual including right to private property, as Indian Fundamental Rights, American Bill of Rights, etc.,

- Limited government is considered important, as government is seen as a ‘necessary evil’. This means, government should be constitutionally limited through separation of powers, checks and balances and defined charter of individual rights.

A limited state with individual liberty and economic freedom is the basis of liberalism. Locke was cautious in balancing individual liberty and scope of government. However, laissez faire theorists and early economists such as Smith, Ricardo and Malthus, Spencer and libertarian and New Right theorists such as Hayek, Friedman, Berlin and Nozick, support minimalist state and give primacy to individual liberty. Democracy has operated and is operating in the context of such liberal background. On the other hand, democratic elements in liberal democracy include:

- Supremacy of people's political power is underlined. The Indian Constitution starts with the word ‘We, the people’ signifying supremacy of the people as the sole source of legitimate power,

- Participation and popular consent of the people through elections,

- Electoral practice as means of expressing consent based on universal suffrage, and

- Popular, periodic, open and multi-party competitive elections as the only source of governmental power and legitimacy

Democracy is identified with universal adult suffrage, free and fair elections, multi-party competition and participation by the people to express their consent and selection or affirmation of leaders. Liberal features of basic liberties of speech, discussion, assembly and other rights including the right to property are required for realization of the democratic practices. Combined with this, constitutional elements such as the rule of law, separation of powers and independent judiciary and bill or charter of rights are considered requisites of liberal democracy. Thus, in the Western sense, liberal democracy combines the features of liberalism, democracy and constitutionalism.

Universal suffrage is based on the principle of political equality and Benthamite principle of ‘one person, one vote’. Periodic, open and competitive elections mean election held on regular intervals, openly conducted by impartial agency (like the Election Commission) and observers and based on multi-party competition. Liberal democracy is characterised by a combination of the liberal and democratic elements as mentioned above. It appears that the adjective, liberal defines the noun, democracy; we generally hear about liberal democracy but hardly about democratic liberalism.

Liberal democracy in its operational aspect is based on the following philosophical and theoretical grounds:

Popular government based on supremacy of the people: Social contract theory places political power in the hands of the people and makes them source of all power to be exercised and enjoyed by governments. Except Hobbes, who makes the people surrender all their power to the Leviathan, other contractualists, Locke and Rousseau, retain supremacy in the hands of the people. For Locke, civil society retains the ‘supreme power’ and for Rousseau, ‘General Will’ is absolute and all-powerful. Its implication is that government must be accountable and responsible to the people. Rousseau was opposed to representative democracy, but Locke provided it's justification. Democracy is a form of government in which the ultimate power rests with the entire community and that community gives its consent as to who should represent them.

Supremacy of people is associated with popular sovereignty. The latter, in turn, relates to participatory democracy. However, it is said that popular sovereignty in itself has no necessary connection with democracy.26 The doctrine that all power should rest with the people does not necessarily mean that this power is to be delegated. In Rousseau, for example, there is no possibility of representation or delegation of power or consent. Rousseau's General Will does not allow possibility of a representative democracy. Democracy can be a useful tool in controlling and limiting authority, which is also the purpose of popular sovereignty. Popular will, Andrew Vincent opines, can be check on centralised authority, but it can be equally dominating. Popular sovereignty is required to check arbitrary deviations

Consent and representation: The doctrine of social contract is an explicit acceptance of government based on consent. Locke's theory of government as ‘trust’ derives from the principle that people has consented to live under a governmental authority. Principle of consent assumes that an individual is not obligated to follow or obey an authority unless personally consents to its authority. Thus, consent provides basis for political legitimacy. Elected delegates carry this consent and form government, decide policies and enact legislations. Government that carries such legitimacy requires people to follow its authority. This form of government is called representative democracy because representatives who constitute government carry consent of the people. Democratic government functions as the trust of the people and accountability of the government to the people is ensured. In liberal view, government and authority is generally seen as opposed to individual liberty. However, a government constituted as per the consent of the individual and representative of her or his interests, wishes and will, is not inimical or opposed to liberty. Representative democracy becomes a mechanism with which authority of the government is limited. The core of the liberal value that individual is the sole decision-maker and rational chooser reflects in his/her choice of who should represent. It also implies absence of this consent when the very interests, wishes and wills of the people is violated by the representative government. This may result in protests, agitations and even violent mass movements.

To enjoy continuous consent of the people and their wishes and wills, representatives need to be in touch with the electorate. This requires eliciting public opinion and maintaining channels of communication with the people. Media, pressure and interest groups and political parties perform the functions of building public opinion and highlighting variety of interests. They also bring together scattered interests and themes present in public opinion and mould them in the perspective of policy-making. For example, there was a need for people knowing about the operations, decisions and impacts of governmental activities on social, economic and political life of individuals. Public opinion in favour of such an act which can provide people the right to get information from the government was debated, discussed and brought to the focus in such a manner that it resulted in the form of the Right to Information Act, 2005.

Limited and constitutional government: If we combine the principle of people's supremacy and source of power with principles of consent and representation as the basis of government, it implies that the ruler should be chosen by the ruled, should be accountable to them and should work in their interests. In other words, ruler should be ‘obliged to justify their actions to the ruled and be removable by the ruled.’27 Locke, Bentham and Mill sought to provide their yardsticks for ensuring government's accountability to the people. In Locke, we find the trio of natural rights of life, liberty and property as the limiting factor; in Bentham the Utilitarian principle of maximum happiness of the maximum number, and in Mill the sanctity and inviolability of individual conduct. Thus, government requires to be limited by the purpose it serves. This limitation is ensured by constitutionally available checks such as separation of powers and checks and balances, independent judiciary checking legislature and executive, and legislature checking and balancing executive; bicameral legislature, one house checking the other, and Bill or Charter of individual rights limiting the scope of interference in areas thus protected for individual conduct. Electorally and politically, the government has limited mandate for a specified time and in a competitive multi-party system, availability of the alternative party further works as limit.

Garner has summarised the benefit and philosophy of representative government as an accountable government and says ‘The theory is that, being freely chosen by their fellow citizens, ordinarily for short terms, and accountable to them for the manner in which they exercise their trust, those who are called to govern will be the most representative, the most competent, and the most worthy of the public confidence’.28 Thus representativeness comes from popular responsibility and control of those who govern.

It is generally agreed that democracy serves the purpose of limiting government by putting its control in the hands of the people. However, some observers have doubted that democracy can be taken as a tool of constitutionally limited government. Sidgwick has pointed out that democracy bears no connection with responsibility. A. G. Sidgwick in his study on American democracy, ‘The Democratic Mistake’ (1912), points out that ‘one of its chief defects lies in the lack of adequate means for securing an enforceable responsibility.’29 We can ask ourselves, as Sidgwick does, whether means such as popular elections, periodic elections, rotation in office, etc. have proved to be adequate to ensure responsibility of and control over the representative government in India. What means people have to check the behaviour of their representatives once they have been elected? Further, there is an intrinsic problem in democracy. What happens when through the same democratic process, racist, criminals, and those who spread hatred are also elected? This was the concern Richard Halbrooke, the American diplomat raised about Yugoslavia in 1990s when he said, ‘suppose elections are free and fair and those elected are racists, fascists, separatists.’30 We have examples of democracy resulting in undemocratic and irresponsible rulers, as in Hitler. It appears that democracy may not be enough check to ensure a responsible government.

Majority principle: Principle of majority is the operative part of consent and representation. In liberal democracy, my consent is to be represented by some one and that too in association with the consent of others in society. This means along with my interests, interests of all must be represented. When we grapple with the issue of how to make the interests of all be represented by one delegate, the principle of majority comes in. By its very nature representative democracy, requires a formula through which representatives are elected. In a bipolar situation having two candidates contesting for the vote in a constituency, absolute majority becomes the basis of election. In a multi-party situation, relative majority prevails. Ironically, in both the cases, even though some of the electorates remain unrepresented, we still call it a representative democracy. This is because, each individual has been given equal political right to choose having one value for his/her vote. Every body having exercised their choices, the candidates securing the majority, either absolute or relative, becomes the representative of the whole geographical constituency. It means once the principle of majority is applied to select a representative, s/he becomes representative of all. Lincoln's formulation of government of the people and for the people (though not by the people) becomes relevant. Once chosen, the representatives constitute the parliament and from amongst them the government. Government thus constituted must work in the interest of all and not merely the majority. Edmund's formulation that a representative should not be a mere ambassador of particular interests but a member of the parliament serves an important guide for overcoming the limitation of the majoritarian principle. Political observers and psephologists have pointed out that in India most of the governments in fact, have been minority governments. This is because in a multi-party contest, relative majority elects candidates. This, in turn, makes a party secure majority of seats despite minority of total votes. Most of the Governments though had majority of seats, they scored less than 50 per cent of votes.

While Locke found majority principle useful operational concept, Mill apprehended that ‘simple majority voting system … allowed the dominance of a ignorant majority over minorities.’31 Mill favoured proportional representation to safeguard the interests of all and not to allow any group to dominate on the other. In terms of threat of majority on individual liberty both Mill and Tocqueville were apprehensive and suggested that majoritarian tyranny should be checked lest individual liberty will be jeopardised.

As a safeguard against the majority principle becoming inimical to minority interests, it has been suggested to provide for proportional representation. Proportional representation means allocation of seats and public offices in proportion to the number of votes polled. This may ensure that the defect of majority principle, in which the interests of the political minority is constructed as part of the majority itself, is taken care of. In India, principle of proportional representation for example is applied in the election of the President of India.

Limitations of Liberal Democracy

Theoretically, there are different perspectives regarding representation on which liberal democracy works. For Hobbes, individual is represented in the Leviathan and unity of those represented lays in the unity of the Leviathan not in the unity of the ruled. By proposing the unity of the sovereign, Hobbes rules out any possibility of representation. Rousseau, on the other hand, seeks representation of each individual in the General Will and independently. However, in Locke, there is a contract of the people with the government as a ‘trust’ and this trust requires representation and periodic renewal of the trust. Every individual has natural rights, has equal consent to the social contract, hence equal trust in government. Then, a contradiction arises. Can each individual claim to have equal trust and representation in government? If so, then each should participate or have representation. This is possible only when there is a direct form of democracy where everyone participates and remains part of the General Will, as Rousseau demands, or a Hobbesian Leviathan as a unified representative of the whole body politic. Lockean democratic theory falters here in its logic. Representation by its very nature cannot be inclusive and has to be based on a principle of exclusion of some. An all-inclusive representative requires to be elected by consensus. Representative democracy with multi-party competition can be only majoritarian, either absolute or relative. Thus, principle of majority becomes the reigning principle in democratic theory and consent of ‘the people’ in representative democracy is confined to consent of the political majority.

If majority is the reigning principle of representative democracy, then John Stuart Mill and Alex de Tocqueville are there to caution us. They consider majority as inimical to individual liberty. While Lockean democratic theory seeks to preserve individual natural rights, his operating principle of majority denies the same to a number of individuals. Macpherson has been critical of Locke's theory and says it is hard indeed to turn the Lockean doctrine into any kind of unqualified democratic theory. By itself, majority based representation becomes partial. Further, the very concept of representation has been doubted on the ground whether individuals or constituencies can be represented at all. Rousseau felt that General Will being a collective will could not be represented by any means. He was critical of the British representative democracy as giving chance to the people only periodically to see democracy.

On the other hand, Edmund Burke, a British parliamentarian, in his address to the city of Bristol on 3 November 1774 after his elections, declared that elected representative is not a mere ambassador of a constituency rather is a member of parliament. He says, ‘parliament is not a congress of ambassadors from different and hostile interests, which interests each must maintain, as an agent and advocate, against other agents and advocates, but Parliament is a deliberative assembly of a nation with one interest - that of the whole …’ He further adds, ‘you choose a member, indeed; but when you have chosen him, he is not a member of Bristol, but he is a member of Parliament.’32 Burke's position saves the majoritarian concept and makes the elected members as representative of the entire community.

Another aspect of representation that comes into discussion relates to territorial versus functional representation. Territorial or geographical basis of representation has been found as incomplete system of representation. It is argued that interests of individuals are not all encompassed in the geographical based interests. Most of the interests of individuals are linked with their functional affiliations such as doctor, teacher, lawyer, government servant, farmer, industrialist, industrial worker, trader, consumer, etc. As such, representation should be based on both functional basis and geographical basis. Laski motivated by his belief in pluralist state and industrial democracy supported functional representation. Sydney and Beatrice Webb also supported twin basis of representation.

Many observers and theorists have evaluated liberal democracy and sought to see whether it serves as a mechanism of accountability and responsibility, maintain individual liberty and freedom, promotes equality or whether democracy has become a mere adjunct of the liberal adjective attached to it. A primary condition of democratic representation is awareness of those who elect representatives. As election of representatives involves rational choice or exercise of individual choice to let someone represent my desires, wishes, wills and interests. It is argued that apathetic, ignorant, poor, uneducated and indecisive masses cannot make rational choice. People are incapable of making selection and choosing representatives that serve them best. Initially, this has kept democratic right of suffrage restricted to a certain wealthy and educated classes. This restriction has been removed through the universal suffrage and a primary assumption in democracy, i.e., political equality, was achieved. This means equal right to vote, seek public office and contest elections and hold public office was extended to all eligible men and women. However, two issues arise here. Firstly, is political equality in itself, without social and economic equality, sufficient to realise democratic participation? Secondly, is representativeness of democracy maintained even though there is large portion of the people who does not vote and are apathetic, unconcerned and uncritically unsupportive to democracy?

It has been generally felt that political democracy requires adequate social democracy, or socio-economic equality to be successful. In various capitalist societies and developing countries, social inequality has been cited as a limiting factor in realizing meaningful and participatory democracy. Radical democrats and New Left writers have suggested that social and economic equality is needed to make political democracy successful. Nobel Laureate, Amartya Sen has argued that for a meaningful participation in the social and political life by the people, ‘expansion of basic human capabilities’ should be provided. He feels that a democratic government has to be responsive to the needs of the people.33 As such, democratic government is needed for wider capability expansion, the latter, in turn, is needed for a meaningful democratic government. Babasaheb Ambedkar has eloquently cautioned us that in the absence of social equality, political equality would be meaningless.

Further, even though political democracy is available, participation of the people may be limited due to apathy towards politics and a general feeling that whether they vote or not, it may not make any difference. In Indian context, this feeling can come due to many factors. It can be due to unresponsive political process, unresponsive and inept political leaderships, political process dominated by certain well-knit families and elites, criminalisation and corruption of political process, etc. However, two important factors of political apathy can be: (i) socio-economic exclusion of the marginalized classes, and (ii) attitude amongst the rich and the elite that politics is a means of redistribution and welfare only needed by the poor and not by them.

Many electoral and psephological studies and surveys depict larger participation of the poor and marginalized people. However, an apprehension remains. Can we completely deny that parties, political brokers and mobilizers induce the marginalized section by money and material gains? We have media reports, eyewitnesses, and allegations of rival political parties of distribution of dhotis (white drapery worn by men), sarees (drapery worn be women), blankets, and of course the mother of all, money amongst people by this party and that party. People are even brought in vehicles provided by the concerned parties and they are made to vote on a particular electoral sign. In this case, the very assumption of democracy based on rational choice of the individual in selecting representative is lost. Further, developmental value of democracy is not realised because participation is induced participation and does not help in the moral and free development of individual self.

It is not uncommon amongst the rich, elite the urban upper class in India, displaying a general attitude that politics is not necessary and is not required by them. This apathetic condition may arise when they associate politics and elections with sectional or redistributive politics, which they oppose. This type of apathy may arise due to reactionary attitude. It is also possible that there is a feeling of political immunity, which comes due to sufficient political connections and economic influence. This leads to the feeling that whichever political party rules, they would have sufficiently networked ministers and leaders and of course bureaucratic officials to take care of their problems and needs. In both the cases, political and electoral process is treated as without any intrinsic value for moral, intellectual and self-development. You dare to speak someone claiming to be a technocrat, professional or management or bureaucratic elite or urban rich or in cases a highly educated person that discussions and debates and election and voting in a democracy are morally and intellectual liberating and self-realizing. You may get the answer bakwas bund karo (stop your nonsense) and if you are lucky and they decide to be diplomatic, you will have haha hah hhaahh (illegible, but they are laughing at you). Democracy is faced with a dilemma of confronting this ‘people’. Unfortunately, this ‘people’ are its assets, they are its nemesis.

Contemporary and Recent Theories of Democracy

To recapitulate, classical democracy includes mainly two broad categories: direct democracy and indirect democracy. The first is also known as participatory democracy because of direct participation of the citizens in assembly to conduct legislative and policy-making functions. The second is known as representative democracy because of indirect participation of the citizens through their elected representatives in legislative and policy-making functions. The liberal democracy is generally identified with representative democracy, though there can be direct liberal democratic methods also, as they obtain in Swiss cantons and some of the American States.

Within the predominant liberal-representative democratic practice, different principles of justification have been attributed to democracy. While Jeremy Bentham and James Madison justify democracy as a government for protection of the individual from dominance of authority and groups through checks and balances, John Stuart Mill justifies it on the basis of development of human personality and moral and intellectual development. These, the protective and the developmental democracy, are variants or part of the liberal democratic arrangement.

Besides, various other names have been given to democracy on the basis of justification and suitability to particular regime and condition. These include, ‘People's democracy’ to generally designate the governmental set up in countries with the dominance of single communist parties, such as China, Cuba, Vietnam, etc.; ‘Guided democracy’ or ‘Basic democracy’ in which representative part of democracy is combined with some form of direct or grass root participation of the people. Ayub Khan advocated basic democracy in Pakistan and Guided democracy was advocated in Indonesia. Many critics have denied democracy the status of rule of the people. They have argued that there is only one possibility; democracy as rule of the elite where elite gets periodically confirmed. Sometimes, it is treated as negotiation amongst groups and groups of elites. As such, elite competition and negotiation amongst groups of elites are treated as forms of democratic practice.

One of the important points of discussion and focus in debate on democracy has been who rules and how legislative and policy making is influenced; alternatively, whether democracy is a rule of the people, or of the majority, or of elite minority or various groups negotiating with each other or of the dominant class. This sociological question leads us to how different observers have described it. Except Marxian conception of democracy, all the other theories that we will discuss below have emerged in the twentieth century. However, all of them share one common focus, that of influence on and exercise of power in decision-making by social groups or classes. Understanding of distribution of power in society changes the understanding of operation of democracy. In classical sense, democracy was either the rule of the people or the majority and its objectives were defined in terms of ethical principles. Recently, democracy has been analysed in the perspective of socio-economic power relations. We call them recent theories of democracy because of their interpretation of perceived changes in liberal democracy in twentieth century and their sociological orientation.

The following theories can be discussed as recent theories of democracy including the Marxian theory:

- Elitist theory of democracy

- Pluralist theory of democracy

- Marxian theory of democracy

Both elitist and pluralist theories of democracy uphold the liberal portion of liberal democracy. But they seek to revise the democratic portion of it. They agree with the basic liberal tenets of constitutionally limited government, private ownership of property and capitalist economy. However, they find changes in the process of people's participation in the political process and decision-making. For elite theory, political participation is a mere periodic ceremony for selecting elite to let them decide further. For pluralist theory, decision making involves plurality of groups rather than the people or the majority per se. Thus, the recent theories are focusing on the changed context of participation and form of decision-making. The radical democrats and New Left thinkers have advocated participatory democracy. This highlights the insufficiency of socioeconomic condition to enable a truly democratic participation in the liberal democratic set up. Marxian theory pronounced the limitation of liberal democracy as being bourgeois democracy working within a capitalist economic system.

Elitist Theory of Democracy

The basic sociological argument that the elitist theory extends with respect to democracy relates to impossibility of ‘rule of the people’. This argument is based on the understanding of power distribution in society and the influence and power enjoyed by an elite minority in society. Democracy as a government is a rule of elite minority and not of the people. Rule by elite minority is inevitable in all societies and there can be only one form of government, i.e., rule by elite. It refutes any possibility of government by the people or of the people, though it can be for the people. Elitist theory divides society into two groups - superior people by virtue of their qualities or social background and those who are masses. Masses are unintelligent and apathetic and elite are organised, capable, intelligent and have leadership qualities.

Sociologists, Vilfredo Pareto and Gaetano Mosca and Robert Michels propounded the elite theory of power distribution and dominance in society. Subsequently, Joseph Schumpeter, Ortega Gasset, Giovanni Sartori, Karl Mannheim, Robert Dahl, C. Wright Mills and others have analysed power distribution from elite perspective. Their conclusion, with minor variations, focuses on one fact, that power and influence in society is restricted in the hands of small elite minority and only they decide and formulate policies. As a result, government can only be by elite and there is no possibility of democracy as government of the people. Alternatively, elitist theory portrays the general mass of people as apathetic, unintelligent and uniformed consequently, and incapable of any meaningful participation. The elitist theory of impossibility of democracy largely draws from the analysis of capitalist democratic societies of the West such as Germany, Italy, the UK and the US. Theorists and political sociologists such as Raymond Aron, Milovan Djilas and David Lane have observed the dynamics of the communist societies and analysed the phenomenon of elite class in these societies.34

Pareto and Mosca conceptualised general perspective on elite rule and view society divided into elite and non-elite. They pointed out that elite provides leadership and are capable of rule. Michels carried out the study of oligarchic phenomenon in political parties. In his study, Political Parties: A Sociological Study of the Oligarchical Tendencies of Modern Democracy (1911) Robert Michels analysed the inner dynamics of decision-making and power distribution of European Socialist Parties and trade unions with particular emphasis on German Socialist Party.35 Michels was concerned with contradictory tendencies - while democracy requires political parties, they themselves evolve as undemocratically organised organizations. On the one hand, German Socialist Party had its aim as opposition to capitalist system and declared to be organised on democratic principles, on the other Michels’ analysis revealed that an ‘Iron Law of Oligarchy’ prevailed within the organization. Political parties, due to complexity of issues in society and apathetic attitude of masses/electorates, developed bureaucratic structure and became oligarchic. Michels suggested that without organization (i.e., political parties or organizations that ensure representation), democracy is inconceivable.

Michels followed a simple line of argument: Democracy requires organization in the form of parties to represent the masses because of vastness and complexity of society, which will not allow any other way of democratic participation. Political parties operate through structured organization with leadership, full time politicians and officials. Due to division of labour, hierarchy and control, decision-making and resource allocation becomes confined in the hands of a small group of leaders. This produces rule and control of small elites. Michels calls this Iron Law of Oligarchy, meaning any organization, political party, bureaucracy, trade union, etc., is bound to degenerate in elite rule. Michels declares ‘It is organization which gives birth to the dominion of the elected over the electors, of the mandatories over mandators, of delegates over delegates. Who says organization, says oligarchy.’ As such, representative democracy, mediated by organised political parties, be it even socialist variety, result in oligarchic rule. Michels wondered how democracy can be ensured when the very organisation that seeks to represent (political parties) is oligarchic.

We can make a distinction between the two set of elitist theorists. The early elite theorists argue that due to omnipresence of elites in every society, there is no possibility of any other form of government than rule of the elite either through circulation of elite or Iron Law of Oligarchy. They deny the possibility of democracy as rule of the people. Pareto, Mosca, Michels and Ostrogorski are champions of this position. There is a second group of elite theorists, who argue that despite elites being present as the leaders, competition between elites and elections at periodic intervals give sufficient chance to the people to express themselves and this choice of elites represents democracy.

Karl Mannheim (Ideology and Utopia 1929) upheld the possibility of democracy even when they agree the presence of elites as the fundamental reality in society. He maintained that though policy formulation was in the hands of the elite, the very fact that the elites can be removed in elections, make the people master. He thinks this very limitation is sufficient proof of democracy and accountability of elite. Elites are selected on the basis of merit and people exercise their choice to select from competing elites. Though Mannheim agrees that political power is always exercised by elites and that ‘actual shaping of policy is in the hands of elites’, he insists that ‘this does not mean that the society is not democratic.’36 In fact, Mannheim's views reflect an attempt to reconcile theory of political elites and democracy.

Joseph Schumpeter (Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy 1942) gave a clear formulation of elitist theory with regard to democratic practice of selection of leaders/representatives. He makes two important departures from the traditional assumptions of democracy - one that the role of the people in a democratic society is not to govern or even to lay down the general decisions on most political issues; and second, that the form of government is to be distinguished by the methods of appointing and dismissing law makers. He assigns the electorate the role of producing government and not governing. For democracy is present if there is democratic method of selecting leaders. For him, democratic method is an ‘institutional arrangement for arriving at political decisions in which individuals acquire the power to decide by means of a competitive struggle for the people's vote’. Like Mannheim, Schumpeter does not deny the possibility of democracy though he adjusts democratic assumption to the theory of elitist democracy.

Democracy is only a mechanism for authorizing governments; it is neither a means to express will of the people nor to develop individual capacities, as J S Mill would have argued.