12

Political Obligation, Resistance and Revolution

Introduction: Political Obligation, Citizenship and Legitimate Authority

Obligation means a condition to perform a duty or fulfil a requirement. Such a condition may arise mainly due to moral or legal compulsions, e.g. obligation to speak the truth or to fulfil a legal contract. Political obligation means obligation of citizens towards the constitution and the state, its orders, commands, rules and authority. At the day-to-day level, it relates to obeying the laws and rules of the State, paying taxes and other dues that the state reasonably seeks. However, there can be circumstances when political obligation erodes and resistance or revolt arises. These may include action of the State and its agencies or the ruling regime, which are inimical to the dignity, life, security and freedom of the citizens and their self-development.

Why should I obey the orders, commands, rules and authority of the State? As a citizen, what is expected of me? As a receiver of rights, what duties should I bear towards the State, its organs and institutions, the various symbols, insignia and emblems that represent the state? When do I get the right to resist the State? In short, how do I reconcile the requirements of supremacy of the State and my rights as a citizen? Does resisting the State amount to treason, harming national sovereignty or becoming an enemy of the State? When do resistance and revolution become justified? When and how my resistance to the orders of the State, its rules and commands is a resistance against national interest and when against a particular class or group interest? Discussion on political obligation requires revisiting these questions and establishing a relationship between political obligation, citizenship and legitimate authority.

Political obligation could be towards the state or against it. When the State is legitimate, there would be political obligation towards it and when the same is coercive and authoritarian or exploitative or colonial, there should be political obligation against it. Gandhiji's Satyagraha, moral persuasion, entails obligation for resisting injustice, brute force and oppressive power of the state, as was the case with the colonial political order.

An authority is a legitimate power. Legitimacy of power comes when people follow the orders, the laws and the action of the state not merely due to its command or force but by willing allegiance. Power without willing obedience is brute force. An authority is legitimate so long as its actions are obeyed and its laws are followed not merely due to force and fear of punishment but primarily because of willingness and allegiance. As Hannah Pitkin says, ‘To call something legitimate authority is normally to imply that it ought to be obeyed…’1

Citizenship is a legally and constitutionally defined identity of each individual who has accepted the supremacy of the authority established by the constitution. Citizens are subjects of the legitimate authority flowing from the constitution and it requires their automatic political obligation, except when their life, security and dignity and their self-development is denied.

As soon as the authority looses its legitimacy, it lacks the claim for political obligation from citizens. At this stage, it may enforce political obligation through force but in this case, it would not be based on willing allegiance. If we ask Green, he will say ‘will, not force is the basis of the State’, and hence, political obligation based on force will be a contradiction in itself. Breakdown of legitimacy is breakdown of political obligation. The problem of political obligation relates to the question: when are the citizens entitled to resist the authority of the State? It means, when does one get the right to resist the State and its power or revolt against it? Can a citizen resist the state when it carries legitimate authority?

Some advocate unlimited political obligation of the individual and demand complete and unquestioned submission to the command of the State and the sovereign. They include the supporters of the doctrine of Force Majuere (obligation primarily because of supreme power of the state), doctrine of Divine Right (authority of the state as divinely ordained and its obedience is religious and moral duty) and doctrine of Raison d’etat (the reason of the State or its interests and ends are supreme in themselves). Idealists Hegel and Bosanquet, Conservatives Burke and Oakeshott and Contractualists Hobbes and Rousseau, all due to different reasons, advocated more or less full political obligation of individual to the authority of the State. On the other hand, Contractualist Locke, Utilitarian Bentham, Idealist Green and political Pluralists Laski, Barker, and others advocate limited political obligation. Anarchists and Marxists admit no political obligation towards the State in a class society.

In India, as the nationalist movement and the struggle for independence grew, the anti-colonial leaders and thinkers opposed any political obligation to the colonial state. Gandhiji's Satyagraha and the revolt of the radical and socialist revolutionaries were resistance against colonial force, though motivation and nature of their resistance were different. Extremist position of Bal-Pal-Rai trio is an example of the right to resistance against the colonial state. However, there were moderate and liberal activists, Naoroji, Gokhale and Jinnah, who advocated a constitutional resistance.

In the Indian context, the colonial legacy of resistance continued after independence. We have revolts against the constitutional means and call for disobedience against the state in the form of Naxalite movements, and various ethnic and linguistic movements. Exhortation for Total Revolution (Sampoorna Kranti of Jai Prakash Narayan) and Seven Revolutions (Sapta Kranti of Ram Manohar Lohia) can be considered a call for limited obligation in the seventies. Such calls were a reaction to perceived situation that the constitution was being overstepped. In contemporary times, we have examples of resistance against the State's developmental policies. These resistance movements advocate protecting the rights of the people to their habitation, surrounding and environment and oppose their displacement for construction of factories, dams, commercial complexes, etc. Do all these resistances form part of resistance against the State or are they merely resistance against a particular form of governmental policy? An analysis of the nature of resistance would help explore how resistance to particular policies or orders does not constitute resistance against the legitimacy of the State itself.

There may be resistance movements, which seek reforms without diluting the overall political obligation to the existing state. Movements waged by J. P. Narayan, R. M. Lohia, etc. are examples of intra-systemic movements that demonstrated resistance against a particular regime and not the state per se. It is said that J. P.'s movement was ‘a struggle against the very system which has compelled almost everybody to go corrupt.’2 The term ‘system’ here implies the prevailing contemporary political scenario and the regime. It did not oppose either the Constitution of the Republic of India nor the Indian State. These were attempts to bring changes while staying within the systemic framework.

There may be extra-systemic movements, which oppose the very logic of the state and seek to change the nature of the state and its authority. Naxalite movement in many parts of India can be cited as an example of extra-systemic movement. Besides, there is opposition to the authority of the state from various groups. Ethnic and religious groups have opposed the Indian state for either seeking more autonomy or complete independence posing themselves as autonomous or independent political entities. Secessionist movements in the Northeastern region (e.g. demand for Bodoland in Assam, independent Nagalim/Nagaland, etc.) and in Kashmir and previously in Punjab (e.g. demand for independent Khalistan) are examples of complete rejection of any political obligation to the state by individuals belonging to certain groups.

How could we differentiate between resistance to a particular regime or policy from resistance to the very constitution or the state? Why and how should we grade different resistance movements such as the Narmada Bachao Andolan, J. P.'s Total Revolution and Lohia's Seven Revolutions, Punjab's and Assam's movements, Naxalite Movements and Terrorists threats? Probably, by classifying them into intra-systemic and extra-systemic and analysing their opposition and resistance in terms of government's policy, regime's ideology, the constitution and the state's authority. Thus, we need to analyse and understand political obligation of individuals as citizens and citizens as belonging to different groups—ethnic, religious, linguistic, ideological and political.

Various grounds have been invoked in support of political obligation; e.g., Hegel's state as a march of God, Machiavelli's dictum that ends of the state justify it means3, Rousseau's General Will, Locke's consent as the basis of the state and the government, Green's will and not force as the basis of the state, Bentham's greatest happiness, etc., have been employed to provide legitimacy to the state and its actions. Citizens as the political constituent of the state carry rights and duties and uphold the laws of the state. Is right to resist a necessary condition for limited constitutional government? Does social movements and revolution mean breakdown of political obligation? We will address these issues to explore the grounds of political obligation and right to resist.

Types of Obligation and Their Relationship with Political Obligation

Let us begin by discussing dimensions of obligation to differentiate political obligation from other dimensions and also to see what linkages they bear with each other: Obligation could be: (i) moral obligation, (ii) coercive obligation, (iii) legal obligation and (iv) political obligation.

Moral obligation: Moral obligation, as the term suggests, arises out of a sense of right or wrong and moral or ethical correctness of a conduct. For example, to help an old age person cross a busy road, not to mock at an impaired person, to tend to a stranger when he or she meets an accident on the road, to give alms to a needy person, or for that matter to speak the truth, are instances of morally obligated conducts. These are instances of moral duties of individuals as part of a social community. One needs not be a citizen of a particular state to do these duties. Whether I am in India or in any other country, I am morally obligated to perform these conducts towards other human beings.

However, there can be situations where one may feel morally obligated to perform certain duties even in a political context, i.e., as a citizen or a subject. For example, against the colonial rule, Indians felt it their moral obligation (besides their political and national obligations) to oppose the British rule in India. Gandhiji evolved a strategy of moral persuasion through Satyagraha to oppose the British rule. While to obey the British rule would have been part of political obligation, in a colonial situation to resist was based on moral obligation of self-esteem, national pride, self-rule and political independence. This suggests that moral obligation of a group of individuals, communities, nationalities, etc. may prove to be a limitation on political obligation. For example, moral obligation of Bangla speaking people as a community or nation in the then East Pakistan proved a limitation on political obligation for Pakistan as a nation-state. Many social movements such as those against untouchability, apartheid, slavery, discrimination against women, etc. arise from moral obligation of the affected members to oppose violation of human dignity in their persons.

Coercive obligation: Coercive obligation arises due to coercion or force behind it. This may suffer from absence of legitimate authority, as was the case with the colonial power when it elicited coercive obligation from the Indian people. However, in a democratic context also, the state uses force to coerce and elicit obedience of individuals to the law and political order and safeguard against rebellion, insurgency, violation of national interest and national sovereignty. It may happen that moral obligation of a group of people to resist the state and the authority, is countered by coercive force and coercive obligation. It is said that Gandhiji had realized that British power had massive coercive force and it would not be possible to counter that with a strategy based on force. To counter coercive obligation, he evolved the strategy of moral persuasion. Coercive obligation can also arise due to inducement by way of material gain. For example, it has been reported that in India, many candidates induce voters by offering material and monetary gains to get votes. When compared, moral obligations are carried because of moral correctness and irrespective of results, while coercive obligations are carried out largely due to fear of punishment and coercion. However, the coercion, which a voter undergoes due to material gain and inducement, is not due to fear of punishment or coercion but due to compromise on the very ideal of political democracy and free choice.

Legal obligation: Legal obligation arises out of requirements stipulated in laws and sanctions that it carries. One is obligated to follow and obey law as it is a command of the state either to protect sovereignty and national integrity, or to maintain law and social order, or to redistribute the resource of the society for equitable and just social order and welfare, or to enforce rights and liberties of groups and individuals. Legal obligations are fulfilled as they are backed by sanctions of the state and not obeying them would be illegal and punishable. While the moral obligation may debate the issue of right or wrong, legal obligation differentiates between legal or illegal.

Political obligation: Political obligation has a specific connotation. It implies relationship of the individual with the state where rights and obligations of both the individual and the State are defined. While the state provides a set of rights and secure them for its citizens, the citizens acknowledge the authority and law of the state. In modern democracy, this political relationship is described as citizenship. Citizens are carriers of both rights and obligations. Heywood describes this relationship when he says, ‘Citizenship… entails a blend of rights and obligations, the most basic of which has traditionally been described as “political obligation”, the duty of the citizen to acknowledge the authority of the state and obey its laws.’4 The extent, nature and justification of political obligation vary based on how the nature of sovereignty, state and its laws and the rights of the individual are viewed.

Ernest Barker in his Greek Political Theory: Plato and His Predecessors has stated that ‘it is the precedent condition of all political thought, that the antithesis of the individual and the State should be realized …’5 He further opines that without realization of this antithesis the ‘problems touching the basis of the State's authority and the source of its laws’ cannot have any meaning. This means, there can be fundamental differences between the autonomy of the individual and his political obligation to the state. Barker hints that this should be realized and reconciled. This means that rights of the individuals and their obligations should be reconciled.

Political Obligation: Supporters and Opponents

Why should the state be respected and its laws obeyed? Answer to this question can vary if one looks from different perspectives. For some, it is because the authority of the state is divinely ordained (Divine rights) but for some others, it is because there is transcendental purpose in the journey of the state (teleos of the Idealists). Yet, for some others, it is because the State draws its authority from contract of the individuals for their own safety and protection of rights (Contractualists). Utilitarian would argue that the State should be obeyed because it maximizes happiness for the maximum numbers. Positive liberals and welfare theorists may support it because it gives scope for moral, personal and self-development and positive condition of welfare.

There can be arguments that the state and its laws are utter coercive instruments and must go. Individuals are better off without political obligation. Anarchists and Marxists argue that the state is coercive and its laws are organs of exploitation and view the issue of political obligation from the perspective of presence or absence of private property. Political obligation in a capitalists system, Marxists would argue, is a slogan for subjugation of the working class to the power of the bourgeoisie. Pluralists, libertarians, feminists and communitarians convey different levels of support and political obligation.

Pluralists, Laski, Barker, MacIver, Figgis, and Follett do not denounce political obligation altogether and recognize the authority of the state. However, they do not give primacy to the state as the sole organ of individual loyalty. They, in a way, advocate limited political obligation. This is due to loyalty of the individuals to the State is mediated by various groups representing different interest. Laski, for example, has identified interests of individuals in terms of member of the State, member of a church, a trade unionist, a free mason, a pacifist, etc.6 As a result, allegiance to the State is neither unconditional nor unmediated. Political obligation to the State cannot be unlimited or unconditional, as it is not the repository of all the interests of the individuals.

Libertarians, such as Nozick, would support limited political obligation to the State because his state is a minimalist state, which is supposed to perform bare minimum functions. While pluralists advocate a limited role for the State because they consider other groups in economic, political and social life equally significant; libertarians, on the other hand, advocate a limited state because they argue for individual liberty and freedom.

Notwithstanding the variations in the perspective of different strands of feminism, at times it looks at the State as an extension of patriarchy, and some other as neutral arbiter. While the first treats the State in terms of monopoly of power and reflection of male domination in society and represents a radical feminist view, the second views the State as accessible to all groups including women and represents a liberal feminist view.7 Empirically, extension of voting rights to women and their representation in legislature and decision-making is less favourable and as such their exclusion from the authority of the State is visible. In the Indian context, for the local-self government (Panchayati Raj), safeguard in terms of designating 33 per cent of seats as women seats has been provided to ensure their fair representation. However, it is true that in many cases women candidates become, or really are, proxy of their male family members.

Communitarian ideas are based on the premise that individuals are not detached, rational or a stand-alone self. An individual's self is shaped and groomed by the community and its values. This means individuals are carriers of social and collective values and community is the main source of rights and duties of the individual. This, in turn, requires addressing the issues involved in rights of communities. From the communitarians’ perspective, political obligation is to be seen in terms of the rights of communities and not the individual. It invokes community-based political obligation.

Political obligation has been supported or opposed by the advocates of different perspectives based on how legitimate the State or its authority is. Various grounds have been invoked to attribute legitimacy to the State. In support of unlimited political obligation, various bases and criteria have been invoked. They include divine rights of rulers; state as realization of certain higher purpose (idealists); political stability and continuity of institutions (conservatives); obligation to community as a source of self (communitarian); supreme strength and irresistible power of the state (Force Majuere); reason of the state or the end and interest of the state being supreme (raison d’etat). Limited legitimacy of the State and its sovereign authority is pleaded based on either consent of the people forming the State and government (social contract), or happiness of the people (utility), welfare and benefit of the people (positive liberals) or autonomy and freedom of groups (pluralists) or individuals (libertarians). On the other hand, equally forceful arguments have been put forward to deny legitimacy to the authority of the state. Those who reject the very idea of political obligation such as the anarchists, Marxian thinkers, feminists and anti-colonialists, do so because they find the State and its authority, laws and prevailing property and political relations as exploitative and discriminatory. For example, Anarchists detest authority or force in any form; Marxian and Neo-Marxian thinkers find the state, its authority and law as reflection of the interest of the private property; Feminists find state as a reflection of patriarchal and discriminatory relations; anti-colonial and civil right and equality movement activists oppose the discriminatory and dominating nature of the state power.

Political Obligation and Resistance: Levels and Orientations

Political obligation may imply obligation towards the State and the Constitution as well as resistance against them depending upon particular circumstances. For example, before independence it became the political obligation of the Indians to resist the colonial state but after we attained independence and had a Constitution of our own, the scope of political obligation and resistance has been comprehensively defined by the Constitution. One the one hand, the Constitution provides a set of fundamental rights, on the other, it provides for reasonable restrictions on the exercise of these rights. These restrictions are to guard against resistance and threat to territorial integrity, national sovereignty, internal security, law and order or public order, incitement to civil war, contempt of court, etc.

Not all acts of resistance amount to end of political obligation. There may be resistance against a particular regime or certain policies and legislations of the regime. Similarly, there can be resistance to policies or ideologies of certain political party/parties. These do not amount to the end of political obligation to the state or the Constitution. As such, while resistance against the state and the Constitution amounts to the end of political obligation; resistance to a regime or its policies or the executive an its actions, etc., may not amount to the end of political obligation.

It is possible that there may not be any disagreement on the Cconstitution but there may be resistance to the government of the day or a regime identified with a particular political ideology. The call for Sampoorna Kranti (Total Revolution) was such a resistance movement, which opposed the Congress regime. There may also be resistance to some of the policies of the government, which does not necessarily represent any disloyalty to the state or the Constitution as such. For example, Narmada Bachao Andolan being a movement to resist a particular aspect of developmental policy that has implication for habitation and displacement of a section of people may not be construed against the state or the constitution. However, the radical and ultra leftist movements against the state or the movement of the ethnic and religious extremists and terrorists reflect erosion of the political obligation. Examples of opposition to the state and its nature could be found in India's opposition to the colonial state, African National Congress's (led by Mandela) rejection of the white dominated state in South Africa, etc.

We can categorize different forms of resistance either as resistance within the overall constitutional and permissible legal framework which accepts the legitimacy of the state authority or resistance which denies any legitimacy to either the constitution or the state. Thus, resistance could be for changes within the systemic framework, i.e., intra-systemic or outside it, i.e., extra-systemic. Resistance expressed by the Naxalite and extremists and terrorist movements in Assam, Kashmir and Punjab are examples of extra-systemic resistance, as they voice opposition to the constitutional means and the sovereignty of the Indian state. They deny any political obligation to the Indian state and its Constitution. There have been various autonomy and statehood movements which demanded/are demanding statehood for Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Uttaranchal, Telangana, etc.8. These movements could be temporary in nature and seek limited a political objective, statehood. Their resistance may cause suspension of political obligation by the members concerned temporarily and its restoration as soon as the demands are fulfilled. These are intra-systemic resistance movements. There may also be various resistance movements, which oppose particular policy of government. For example, pro and anti-reservation protests are oriented towards particular policy. Though it has constitutional implication, opposition to a particular policy does not mean rejection of political obligation to the Constitution. These would also be examples of intra-systemic resistance movements.

Grounds and Limits of Political Obligation

Political Obligation during the Greek Period

From Pericles to Aristotle, democracy was cradled in Athens, one of the most celebrated Greek poleis, city-states. The polis was a celebration of public life. Such was the importance they attached to political life and participation of individuals in the public life of the polis that those who were uninterested in the affairs of the polis, the Greek called them idiots—from which we derive the word idiot.9 Such an understanding of political and public life was germane to the political obligation that the polis sought from its citizens. Aristotle's phrase that state is prior to the individual seeks to establish teleological priority of the state. Like the nature of a seed is to be a tree or a plant, nature of man is to be a political animal and to realize himself in the state. The purpose of human life is to realize one's self and freedom in association with fellow beings. If this was the realization and reconciliation of, what Barker says, the antithesis between the individual and the state, the Greeks resolved the issue of political obligation by making the polis a cradle of an individual's freedom ad self-realization. Greek political thought did not seek ground for political obligation from its citizens away from the very purpose of the polis, betterment of the citizens. In Greek political thought we find endorsement of political obligation based on teleological ground in which the purpose of good life justifies obedience and affiliation to the state.

Their justification for political obligation was grounded in the very nature of human life, as Aristotle would say, ‘state is a creature of nature and man is a political animal’ or ‘to live alone … one must be either an animal or a god’. State was found to be the highest level of social and self-sufficient organization. This self-sufficiency was not merely in terms of territorial, economic and material but for moral and mental development as well. State, as Aristotle says, came into being for the sake of life but continues for the sake of good life. If this was the end of the State, political obligation of the individuals meant their own benefit and development.

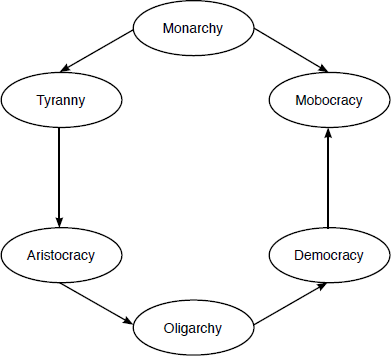

However, the Greek poleis were not free from stasis, civil strife or discord between the rich and poor and factional competition and their alignment across different poleis. Plato complained of factional strife and identified this as a reason for instability.10 Repeated corruption (in the sense of degeneration) of the constitutions and form of governments from monarchy to tyranny; aristocracy–oligarchy and democracy to mobocracy was a staple complain of both Plato and Aristotle. Though overall loyalty and obligation to the polis was forthcoming, Greek political life was not without resistance. Aristotle talks of revolutions as cyclical changes in the forms of government. This would be possible when one class takes over from the other class (class in the sense of rich, poor and middle class).

Political Obligation During the Roman Period

Greek political theory celebrated the polis but did not differentiate society from the State. Polis was all-encompassing and lack of distinction between the State and society meant lack of any distinction between the rights of individuals and authority of the polis. The two were merged and political obligation was as much a matter of civic life as could be for political life. There was no right to resist or deny political obligation to the polis, though form of constitutions and rule of social classes kept changing.

It was the evolution of the Roman legal system that helped differentiate and ‘establish the distinction between “state” and “society”, or between public … and private ….’11 The idea of the state as a distinct legal entity emerged during the Roman period. Polybius and Cicero, the two great political thinkers of Roman period, argued for and favoured the system of checks and balances within the state. Both of them favoured balancing monarchical elements (represented in the Consuls), aristocratic elements (represented in the Senate) and the popular democratic elements (represented in the Tribunes). A harmonious balance between the three elements was considered as the basis of balance not of social classes as Plato and Aristotle thought, but more of political power.12 Stuart Hall maintains that the concept of Roman citizenship was defined by law rather than by strict territoriality. This enabled inclusion of ruling classes of other cities after conquest as Roman citizens.

Two other important concepts that the Roman political theory and legal system added were lex regia and Imperium. Lex regia was a Roman law doctrine ‘which argued that power was conferred by the people or populus’.13 The idea of Imperium implied ‘discretionary power to perform acts in the interest of the whole political organization.’14 According to Andrew Vincent, Imperium was obtained by consuls (monarchical elements) and later by the emperor from the senate (the aristocratic element), army or people via the doctrine of lex regia. In fact, doctrine of lex regia and Imperium gives a distinct meaning to the theory of sovereignty in the Roman period.

The distinction between the State and society, concept of citizenship based on law, doctrines of balance between political power, lex regia and Imperium point towards two things. One, that power of the ruler was derived and limited and second, that the state and sovereignty were subject to law and lex regia. Roman political theory contributed the idea of law as the basis of state power. As such, political obligation was justified on the basis of legality and popular basis of power. Cicero eloquently declared that ‘We obey laws in order to be free.’15

Subsequently, however, as Andrew Vincent explain, the doctrine of Imperium was conceived as related to political power independent of its popular source and the doctrine of lex regia was shadowed by the doctrine of legibus solutus (what pleases the prince has the force of law).16 This doctrine of legibus solutus might have led to the formulation of the doctrine that the emperor possessed fullness of legal power and, in turn, that the centre of both legal and political power was the emperor. This reflects a shift of ground of political obligation from impersonal law to the emperor as repository of political and legal power.

Political Obligation versus Christian Obligation

With the emergence of Christianity and decline of the Roman period, the issue of political obligation came to be debated from political as well as religious angles; what obligation a Christian bears to a king. The dictum that was put before the people appeared to be what Jesus had said and St. Paul had dutifully expressed to the Romans before he was executed in Nero's Rome, ‘Render therefore unto Caesar the things which are Caesar's, and unto God the things that are God's.’17 This was a dictum of a twofold obligation, civic as well religious obedience. Gradually, this twofold duty became intense and by the time St. Augustine proposed the division between the spiritual and the temporal realms in terms of the earthly city and the City of God, the conflict between the church and the state had already dawned on Europe. Between the fourth to the sixth century AD, St. Ambrose, St. Augustine and St. Gregory advocated church's autonomy and superiority over the spiritual and ecclesiastical matters. This superiority included the emperor, as the emperor, like any other Christian, was considered as a son of the church. The upshot of this argument was that a Christian bears primary obligation to church and even the emperor is not above this obligation. This was the idea of a ‘universal Christian society’ in which political obligation was secondary and subject to the primary Christian obligation.

Travelling through the Two Swords doctrine of Pope Gelasius I in the fifth century AD, the church-state controversy came to clash in the form of spiritual supremacy versus imperial omnipotence in the eleventh century AD when Pope Gregory VII and Henry IV came to deny each other's claim. The doctrine of the Two Swords argued that God had given two swords—one to the Pope to run the spiritual matters and the other to the emperor to run the temporal matters and thus, the two should not interfere with each other.

Papalists, John of Salisbury in the twelfth century AD and Thomas Aquinas in the thirteenth century AD championed the cause of Papal supremacy. John of Salisbury argued that originally both the swords belonged to the church, one of which was transferred to the king later. By implication, he argued that king was the representative of the church and the latter was justified in seeking subordination of the king to the church. Aquinas also supported subordination of the state to the church, as the latter was considered the crown of social organization. Both John of Salisbury and Thomas Aquinas advocated limited political rule and disliked tyranny. Thomas Aquinas maintained that rule must be according to law and resistance to tyranny was not sedition. Though, otherwise he considered sedition a sin.

On the other hand, Imperialists, Marsiglio of Padua and William of Occam argued that the church has limited function related to spiritual matters and hence, its authority must be limited too. They advocated subordination of the church to the state in all temporal matters.

The controversy left the believers and subjects in the hands of dual obligation. However, the controversy rendered even the civic authorities as if they carried divine sanction. This was because the church argued that the temporal sword came from God. Though the controversy gave credence to two forms of obligations, Christian obligation and civic obligation, it was a foregone conclusion that in case the two came in conflict, the primary obligation remains to Christianity and the church, not to the civic authorities. Second, implication was that the state was never granted a secular status and was always considered as an integral part of the Christian commonwealth. According to St. Augustine's division of the earthly state and the City of the God, it appears that neither justice nor freedom could be possible in a non-Christian state. As such, sanction to full obligation would be available when both the church and the state flourish as part of the Christian commonwealth. We can infer that the doctrine of obligation under Christianity, though permitted political obligation to civic authorities, nevertheless, remained a doctrine of religious obligation. Third, implication of this was related to the emergence of the divine rights theory of kings. Kings in the medieval period sought to sanction their rule and power by invoking divine inheritance of their power. Fourth, implication was both bloody and undesirable. It so happened, particularly in England and France, that the king/emperor belonged to a different sect of Christianity than the subjects who belonged to certain other Christian sects. In that case, religious obligation and political obligation remained un-reconciled, as obligation of such sects of subjects to the king was opposed to their religious obligation. This led to many a civil strife and religious persecutions.

Political Obligation Under Feudal Europe

Added to this duality of political and religious obligations, feudal Europe witnessed diffusion and dilution of even political obligation. Feudalism is characterized by diffusion of power, fixed social hierarchies and a rigid pattern of obligations and services. This means that unlike sovereignty of the nation-state, the feudal society had no centrally located power, no concept of citizenship, defined rights and duties and impersonal order. It was based on hierarchical relations of obligations and services, where lord, vassal, barons and serfs are related in a chain of obligations and services. While the lord stood at the top and granted land and other privileges including protection to vassals and barons, the latter were obligated to provide military and political support to the lord. The vassals and barons, in turn, also sublet land and other privileges to those below them. This had created sub-infeudation (chains of feudal relations). At the bottom were the serfs who had nothing to receive but only to work and render. Feudalism in Europe and in India18 made holding of land and performance of military and political obligations linked. During the feudal period in Europe, due to decentralization of power and feudal relations, political obligation was in fact absent. At the most, it manifested in economic and military obligations of vassals and barons to lords and latter's to the king or the emperor.

Political Obligation Under Islamic Injunctions

Unlike the Christian tradition (the church-state controversy), in Islamic tradition, the temporal and the spiritual are not dichotomized. The state and political obligation are not outside the Quranic vision. As Karen Armstrong, who has written several books on religions, in her Islam: A Short History, says, ‘A Muslim had to redeem history, and that meant that state affairs were not distraction from spirituality but the stuff of religion itself.’19 If this is the case, religious and political obligations are the same.

However, to understand the scope of political obligation in Islamic vision, we may need to see how Islamic jurisprudence interprets different political obligations for different types of political relations based on Islamic and non-Islamic rule. The whole world is divided into Dar al-Islam and Dar al-Harb. While Dar al-Islam stands for the House of Islam, i.e., territory and area under Islamic rule and control, Dar al-Harb stands for the House of War signifying area or territory ruled by non-Islamic rulers. For a Muslim inhabiting Dar al-Islam, political obligation, being part of religious obligation, is unconditional and absolute. However, the problem arises in Dar al-Harb. Should a Muslim residing in a territory ruled by non-Muslims render political obligation to the state? What would be his political obligation to the Dar al-Harb when a Muslim or a non-Muslim from outside attacks it? It may be noted that in the context of the 1857 Revolt in India against the British colonial power, the issue of political obligation of the Indian Muslims to the colonial state was a matter of debate. India ruled by the British was a Dar al-Harb for the Indian Muslims. A large section of Indian Muslims applied this concept to justify their opposition to the British rule and rally against it.

Kamal Ata Turk abolished the Caliphate, the seat of Muslim politico–religious power in Turkey after the First World War and consequently, there is no central seat of power to direct the Muslims all over the world in their politico–religious obligation in a particular way. Emergence of nation-states means Muslims are residing along with followers of other religions under different political dispensations, ranging from democracy to authoritarian rule to socialist rule, etc. and are equal citizens of these nation-states.

Political Obligation in Indian Political Thought

The theory of divine origin is found in the Manusmriti,20 Shantiparvan of Mahabharata and in Kautilaya's Arthásastra. These ancient texts have talked about political and moral obligations of the subjects by implying the divine origin of rulers. L. N. Rangarajan, in his translation of Kautilaya's Arthdsastra, states that while Dharmashastras are addressed to the individual, teaching him his dharma and regard deviations as sin, ‘the Arthashastras are addressed to the rulers and regard transgression of law as crimes to be punished by the state.’21 Vaivasvata Manu (as he was known, son of Vivasvat) and Kautilaya or Chanakya advocated divine origin of kings and sanctified the rule of emperors and princes. Manusmriti mentions that a king is an incarnation of the eight guardian deities of the world—the Moon (Chandrama), the Fire (Agni), the Sun (Surya), the Wind (Vayu), the Lord Dispenser of Favour (Indra), the Lord of Wealth (Kubera), the Lord of Water (Varuna) and the Lord Dispenser of Punishment (Yama).

In his Arthádsastra, Kautilaya too presents the king as occupying the position of both Indra, the god who is dispenser of favour and Yama, the god who is dispenser of punishment. A combination of these two qualities in the king makes him possess divine rights. Kautilaya's king emerged because of prevalent disorders in society. He mentions that Manu was made the king to bring order and welfare to society. In fact, by invoking such a theory of origin, Kautilaya justifies the obligation of the people not only to pay obedience as religio-moral duty but also assign ‘to the king one-sixth part of the grains grown by them, one-tenth of other commodities and money’.22 This enjoins upon the subjects not only to pay political acquiescence to the king and the State, but also part with a portion of their products as share of the king and the State. Kautilaya's Arthdsastra elaborately discusses the scheme of taxation and share of produce that the subjects are required to part to the king.

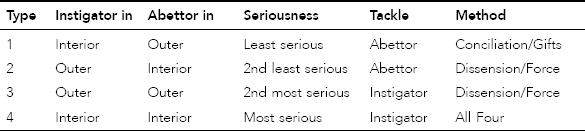

Political obligation in such a scheme appears in two ways: one, subjects have religio-moral duty to obey the king as a divinely ordained power, and two, they should pay taxes and share in their produce to the king. Modern citizens are no different; they oblige by paying homage to the nation's flag and the national sovereignty on the one hand, and variety of taxes on the other. Kautilaya's rulers were obligated to render a threefold duty to the people; protection from external aggression (Raksha), administration and internal order (Palana) and welfare of the people (Yogákshema).23 In Kautilaya's scheme, we have political obligation of the subjects and reciprocal duty of the king. Kautilaya devotes a separate chapter in his Arthdsastra on revolts, rebellion, conspiracies, treason and disaffection amongst the subjects and provides elaborate methods for dealing with them. He also discusses the types of revolts, their instigators, abettors and seriousness and methods of tackling them. We will discuss these in the section on revolts and revolutions.

Issue of political obligation in medieval India was partly to be viewed with reference to feudal relations and partly with reference to the relationship between the majority Hindu subjects and their rulers—Hindu, Muslims and others. Due to the feudal nature, political obligation was not towards any central authority but in a hierarchically defined chain of obligations and services. In different parts of India, pattern was not uniform and affiliation was largely to local feudatories or rulers. During the rule of certain Muslim emperors, non-Muslim subjects were required to pay poll tax (Jaziya), though this was neither permanent not a favoured practice.

It may be mentioned that early Islam did allow followers of other religions, particularly the Jews, Christians and Zoroastrians to stay in Medina and other parts covered with Islamic religion though they had to pay poll tax. Karen Armstrong notes that it was common among the Arab Tribes to extend protection to weaker clients (mawali). After the onset of Islam, the followers of other religions became protected subjects (dhimmis) and paid poll tax in return for military protection and were permitted to practise their own religion.24 During the period of Muslim rule in medieval India, poll tax on followers of religions other than the religion of the ruler might have the same root and the same logic. Political obligation of non-Muslims in a Muslim ruled state was mediated by the poll tax. This was in lieu of military protection and permission to practice own religion. As mentioned above, only a few rulers applied this and Akbar disallowed it during his time.

During the medieval period, because of an absence of a secular concept of citizenship, political obligation was either feudal or religious. Political obligation of the Indian people during the early British rule was based either on feudal and colonial relations. It was only after the political consciousness of nationalism started bringing people together that the problem of political obligation in a colonial context was debated and questioned.

Political Obligation During the Colonial Rule in India

The British rule in India was characterized, amongst others, by: (i) feudal relations—zamindari, mahalwari and ryotwari based on how land right was granted to the people, in individual capacity or as village, and how revenue collection is patterned, and (ii) political relation—subjects bearing the laws, codes and regulations framed by the foreign rule. There was no political participation of the people and political obligation was intermixed with feudal and colonial relations. Understanding of the nature of colonial relations is important for defining political obligation towards a state or political set-up that was foreign.

Colonial rule as modernizing factor: A group of early English educated Indians, known as the Derozions, and some of the great social reformers such as Raja Rammohan Roy and others who felt that British rule had a positive and beneficial impact. Raja Rammohan Roy, influenced by Bentham's Utilitarianism, measured social and religious practices on the scale of social utility and rationality. He aimed at modernization and social reform by use of rational thought and modern education. Like Bentham, Rammohan Roy reposed great faith in legislation as a means of reform. This could be possible when one accepts the reformist character of British rule and their legislation, as a means of social reform and modernization. His campaign against sati, polygamy, casteism and support of widow remarriage and later on provided inputs for the British rule to bring social legislations. By their very nature, reformist movements were not aimed at denying political obligation to the colonial rule. Rammohan Roy's faith in the British nation as protector and promoter of freedom, liberty and rationalism led him on 15 November 1823 to declare that Among other objects, in our solemn devotion, we frequently offer up our humble thanks to God, for the blessings of British rule in India and sincerely pray, that it may continue in its beneficent operation for centuries to come.’25 His prayer at least was not denied for one and a quarter of century. By the time, God could get busy with other prayers and the British rule would discontinue in its beneficent operation, it had already brought a variety of social reform legislations, including abolition of sati in India. Under the social reform perspective, political obligation to the colonial rule was not denied.

Colonial rule as benevolent constitutionalism: There was a stream of thought in India which reposed trust in the constitutional and liberal tradition of British democracy and hoped that the colonial rule would treat the Indian people in the same way that the British government treats its citizen back home. This was the school of liberal and moderate thinkers and activists, Dadabhai Naoroji, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Pherozeshah Mehta, S. N. Banerjea and early Mohd Ali Jinnah. Naoroji and others believed in the civilizing role of the British rule in India. However, they were disappointed by the fact that the Indians under the British rule, instead of being treated as ‘British citizens and hence entitled to the rights and privileges that pertained to British citizenship, ’26 were denied the same. Their liberal optimism led them to believe that some type of political and constitutional relationship with the British government far from being inimical to freedom and liberty would be beneficial to it. They advocated not a theory of nationalist liberation and radical political resistance but one of constitutional linkage and moderate representation. They supported political obligation to the British rule and when resistance was to be offered, that would be only constitutional and representational. They insisted on constitutional, legal and political obligation to be rendered by the Indians to the British rule. Even while agreeing that economic policy of the colonial rule was, what Naoroji accepted in his Poverty and Un-British Rule in India, a ‘drain’, they reposed faith in the benevolence of the colonial rule.

Colonial rule as cultural and national invasion: One stream of thinkers believed that British rule in India constituted cultural and national aggression and must accordingly be removed. They offered a nationalist and national renaissance perspective. These activists and thinkers included Dayananda Saraswati, Swami Vivekananda, Aurobindo Ghosh, B. G. Tilak, Veer Savarkar, Hedgewar, M. M. Malaviya, Shyama Prasad Mukherjee and others. They believed in Vedic idealism, revival of ancient glory and wanted Indian renaissance as the basis of regeneration and awakening for national liberation. They offered cultural, national, religious and political resistance to the colonial rule and nourished a dream of bringing ancient glory to modern India. They denied any political obligation to the colonial rule.

Dual role of colonial rule: In the Marxian analysis, imperialism is connected with capitalism and Lenin aptly demonstrated this in his book, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1917). New Liberal theorist, J. A. Hobson in his Imperialism (1902) also demonstrates how capitalist system at home requires outside markets and creates imperialist pressure. Marx, however, in a series of articles in 1853 in the New York Daily Tribune, talked about the destructive as well as regenerating role of British rule in India.27 According to Marx, destruction of the self-sufficient village economy, neglect of irrigation and public works, introduction of English landed system and private property in land, heavy duty or prohibition on import of Indian manufactures to England and Europe meant destruction of the Indian economy. Much before Dadabhai Naoroji (Poverty and Un-British Rule in India) and Romesh Chandra Dutt (Economic History of India) presented their economic critique of the British rule as a drain on India's economy, Marx had estimated the drain. In his Das Capital, he had estimated that ‘India alone has to pay £5 million in tribute for “good government”, interest and dividends of British capital, etc., not counting the sums sent home annually by officials as savings of their salaries or by English merchants as a part of their profit in order to be invested in England.’28 On the other hand, according to Marx, the regenerative role of the British rule manifested in the form of political unity, press and education system, emergence of Indian middle class, communication and transport, Indian market, etc. This promised ‘transformation of India into a reproductive country’ and lay down ‘the material condition for advance. With regenerative condition and new advance, Indian people would have to gain liberation from the imperialist power. Lenin gave a call to oppressed nations to seek their liberation and inserted into Marx's famous slogan ‘and oppressed nations’ to appear as ‘Proletarians of all countries, and oppressed nations, unite.’29 In the Marxian analysis, there is no room for political obligation to an imperialist-colonialist state.

Colonial rule as Dar al-Harb: In the context of revolts of 1857 and gathering opposition against the British rule, a section of Muslims identified the nature of the colonial rule as Dar al-Harb. This means the territory occupied by the colonial power was House of War and opposition to the same was justified and a moral duty. Theoretically, this was a doctrine of political resistance, which enjoined upon the Muslims to oppose a colonial rule.

Colonial rule as moral and national subjugation and colonial state as repository of brute force: For Gandhi, industrialism and capitalism were integrally linked to the Western civilization, which he proudly and unequivocally denounced in his Hind Swaraj (1938). Colonialism represented not only these evils but above all represented brute force. Gandhi as a critic of the state and its brute force was heavily influenced by the writings and methods of Henry David Thoreau. In fact, civil disobedience and passive resistance advocated by Thoreau in the context of American slavery very much became Gandhi's weapon as Satyagraha. He treated colonialism as moral and national subjugation and considered the colonial state, or for that matter, any state, as repository of brute force. Gandhi's approach to political obligation then was unique. He advocated minimal or no political obligation and offered a theory of resistance in the form of Satyagraha or moral insistence.

Political Obligation Under Post-renaissance European Political Thought

Machiavelli and Raison d’etat as basis of political obligation: Machiavelli provides the keyhole to peep into the post-Renaissance political theory and why does the state require its subject to pay obedience. In his Prince (1532), Machiavelli put forth the justification that the interest or the end of the state, which is acquisition and maintenance of power, is prime and all means are justified to secure that. This implied that the state has its own interest and reason and the doctrine of raison d’etat, reason of the state, may trace its link from there. By doing so, Machiavelli took the state out of the medieval labyrinth of the state–church controversy, on the one hand, and justified the authority of the ruler on secular ground away from the divine right speculation. In such a scenario where interest of the state was primary, political obligation was unconditional and unlimited. In fact, reason of the state arguments might have provided fodder for the development of absolutist states30 in Europe.

Doctrine of consent as basis of political obligation: While the raison d’etat as a secular basis and divine rights as religious basis were employed for justifying authority of the state and ground for seeking obedience of the subjects in sixteenth- and seventeeth-century Europe, a major theoretical change was introduced by the doctrine of social contract. Three thinkers, Hobbes (Leviathan), Locke (Treatises on Civil Government) and Rousseau (The Social Contract) talked about the contractual basis of the state and its authority/sovereignty. This means, the source of authority of the state was made out to be the consent of the people themselves who to escape from the undesirable condition of the state of nature, contracted with each other to establish the state and institute a common authority and government. This doctrine of social contract became the cornerstone of political obligation based on consent during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and informs the principle of representative governments in present democracies. While we have discussed the doctrine of social contract in detail in the chapters on the state, it would be appropriate to recall a few important points considered necessary from the point of view of political obligation.

Before Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau discussed their theory of contract and consent in late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, Johannes Althusius advocated contract as the basis of emergence of society and government.31 In dealing with the question of obligation to the community, Althusius supported the idea that a rational way of conceiving obligation was to attribute it to promise of the individuals and this promise was the contract made by them. This makes obligation self-imposed and not imposed by force. The principle of self-imposed, consent-based political obligation was supported by Thomas Hobbes in Leviathan, Samuel Pufendorf in his book on natural and international law in 1672, John Locke in Two Treatises on Civil Government and J. J. Rousseau in The Social Contract. In present times, John Rawls in his A Theory of Justice has used principle of contract and consent to propose his concept of distributive justice and self-imposed political obligation.

Hobbes's contract by the people is against the undesirable and brutish, solitary, poor, nasty and short condition of the state of nature. It is a contract amongst the people to hand over all the individual freedom that they have to one body—the Leviathan or the Sovereign. The latter, however, is neither a party to this contract nor bears any obligation. Hobbes makes the consent of people to the Leviathan absolute, irrevocable and unlimited; otherwise the only prospect is reversion to the state of nature. In the state of nature, no one's product of labour is certain and no one's life secure. In Hobbes's scheme, the primary motive or objective for such consent is to secure the condition of life under a sovereign authority. Implication of Hobbes’s theory of consent is absolute obligation of the subjects/citizens towards the political authority without reciprocal duty from the latter.

It does not give much room for resistance either. This is based on the understanding that existence of the state and authority is better by any standard than absence of the same. Thus, Hobbes requires political obligation to any authority in existence and justifies claim of the ruler to seek obedience even though the ruler is bad and oppressive. It is possible that Hobbes was writing to justify the hold of Stuart kings in England against the demand of the people. However, his fear of collapse of the authority and reversion to the state of nature in case there is resistance and end of political obligation is due to lack of proper differentiation between the state and the government, which Locke introduced. As a result, as Heywood says, ‘For Hobbes, citizens are confronted by a stark choice between absolutism and anarchy’32 and hence they need to offer full political obligation.

Leviathan's authority is legitimate, primarily, because subjects have consented to its power. Virtually, nothing can be pleaded against its power, neither right nor justice, nor law of nature, nor law of God, nor conscience, nor any natural right except one, not to kill someone. The latter is very logical for the doctrine of contract and consent, which makes Hobbes concede the right to resistance. Primary natural right that justifies existence of the Leviathan is right to life of the individual. If Leviathan fails to protect, disobedience to its authority is justified. Leviathan ‘cannot command a man to kill himself’ and ‘man owes no obligation to an authority that fails to protect him.’33 This is the limitation on Leviathan and ground for resistance conceded by Hobbes.

Unlike Hobbes who favoured almost an absolute form of political obligation, Locke presented a doctrine of limited consent and limited political obligation. Locke portrayed the very cause of social contract as protection of certain natural rights, namely rights to life, liberty and property. These rights are available in the state of nature but are not fully enjoyed due to lack of an interpreter, executor and adjudicator of natural law. To protect and enjoy these rights, a social contract is entered into. This means rights, which are available to the individuals before their entering into a political community must not be violated in the civil society or by the state authority. To what benefit the state and its authority is if the very rights for which they are instituted are circumscribed and violated. The consent of the individuals in contracting and surrendering certain rights to escape from the state of nature is twofold: one, to form a society and political community, which will be represented by a government as a trust of this political community, and two, to institute a government with a legislator, executor and adjudicator. Locke's doctrine of consent and contract result in a limited government and differentiated from the state or political community. Unlike Hobbes, government is a representative of the political community and the latter is politically supreme.

The implications of his doctrine of limited consent are: (i) it makes state and government separate, (ii) allows political supremacy to stay with the political community, (iii) treats government asa trust of this political community for protecting the natural rights of life, liberty and property, and (iv) makes failure to protect these rights a breach of the trust reposed in the government by the society, and hence reason for resistance and revolt. A revolt or rebellion against a government that has failed in its trust, unlike Hobbes, does not mean dissolution of the state. In Locke, it is only change of a government. This is what was happening during the English Revolution, 1688. Since the political community reposed supremacy, it can change the trust from one government to the other.

Interestingly, by using the same doctrine of contract and consent, while Hobbes sought to put the fear of anarchy if the Stuart kings were overthrown by the Revolution, Locke showed a direction for limited constitutional government. Locke's is a doctrine of limited consent and limited political obligation; political obligation to the extent the government protects natural rights.

Jean Jacques Rousseau, son of a watchmaker father and an affluent mother, born in Geneva, despite having struck affection for a number of ladies of all age groups, swore by the beauty and divinity of Theresa to whom he bore several children without being married to her, wandered without much social bondage, lived almost in exile and confessed of his misfortunes and conspiracies his friends forged against him.34 This Rousseau of ours celebrated the noble savagery of humankind and the innate goodness of the human nature.

In Rousseau, we find two accounts of social contract, one in his Discourses on Origin of Inequality and other in his The Social Contract. We will confine ourselves to the second account in which Rousseau gave primacy to civil society and its General Will as the protector of real liberty of the individuals. As a result of social contract, General Will emerges as the supreme authority. It represents common interest and collective good, as opposed to the particular or private will that represents the selfish interest of individuals. General Will, being representative of the real will (will that is in every member of society, which wills common good) of all members of the society is a repository of real liberty. In following General Will, every one follows, his or her own will and does not subordinate to any other authority that is external to him or her self. Rousseau identified true liberty with civil liberty that comes in submitting to the General Will. As such, Rousseau's is a doctrine of unlimited, unconditional and absolute political obligation, as it is an obligation to common good. Since true freedom lies in following the General Will, any one deviating from that, Rousseau says, will be ‘forced to be free’.

Amongst the three social contractualists, Hobbes and Rousseau demand unlimited political obligation and Locke postulates limited political obligation. Hobbes's doctrine results in absolute sovereignty, Locke's in political sovereignty and Rousseau's points towards popular sovereignty. Hobbes and Locke were witness to the Glorious Revolution of 1668 in England that was directed against the Stuart dynasty. This was a prime example of political resistance and defiance of political obligation. Hobbes thought it was anarchic, Locke considered it a result of breach of trust of the people by the rulers. Two other revolutions that came after more than a century, the American Revolution in 1776 and the French in 1789 were also prime examples of political resistance. Rousseau's writings are considered to have influenced the French Revolution. In a way, the doctrine of consent and the political resistance that manifested in the three revolutions, charted the road for political obligation based on constitutional and limited governments, rule of law, representative character of the authority and supremacy of the people as source of all political power.

Thomas Paine, an Englishman who left England and went to America, supported the American and the French Revolutions and republican form of government. He was opposed to the British monarchical system. He wrote, The Rights of Man in celebration of both the French and the American Revolutions and against Edmund Burke's conservative reaction to the French Revolution. While Tom Paine was not a supporter of social contract theory, he supported the natural right doctrine on teleological basis.

Conservatism and natural duty as basis of political obligation: Edmund Burke (1729–97), who is considered ‘as the father of Anglo-American conservative tradition’ opposed the doctrine of rights of man and argued that mutual obligations and rights of people rooted in tradition and experience are more important than abstract conceptions of rights. His Reflection on the Revolution in France is considered a testament of conservative position against revolutionary upheaval. He argued that rights of man not rooted in tradition and not based on mutual obligations is abstract, destabilizing and speculative, as it recognizes pre-social rights. Burke was a supporter of rights and obligations rooted in historical experience and accumulated wisdom.

Implication of conservative tradition for political obligation is that it seeks to root obligation of the individual as moral and social duty and is based on mutual respect of the rights of others, respect for institutions of the society, established authorities and law, customs and tradition. Political obligation becomes what Heywood says, ‘natural duty’ and moves away from the idea of voluntary behaviour and consent. Conservative perspective on political obligation poses an alternative to the consent basis of political obligation. In contemporary times, Michael Oakeshott (1901–90) and Irving Kristol (1920–) have supported conservatism. Oakeshott in his Rationalism in Politics and Other Essays has supported ‘non-ideological style of politics’ and political obligation on the basis of customs, tradition and civil association.

State as reflection of a higher goal: Idealists such as Hegel (Philosophy of Right) and Bosanquet (The Metaphysical Theory of the State) attributed the state an external, higher and idealistic purpose and treated it as the ‘march of God on earth’. Hegel holds that Spirit or the divine reason manifests in each institution and the state is the highest reflection of this divine reason or Spirit. For Hegel, history is the history of journey of Spirit and the state is a special manifestation of this journey. This journey of Spirit is also a ‘progress of the consciousness of Freedom’. By associating the state with some divine purpose, Hegel gives it an exalted position. Since the state is a manifestation of Spirit and divine reason, individual freedom can only be realized in this divine journey. Individual freedom is to be realized only when one submits to this divine reason. Hegel's argument means complete submission of the individual to the will of the state. Hegel's is a doctrine of unlimited and absolute political obligation. The state, even though imperfect should always be obeyed, as disobeying would amount to disobedience to the divine scheme of things.

Common good and fulfilment of man’s moral capacity as the basis of political obligation: T. H. Green, an English idealist, supported Hegelian's concept of ‘Divine Spirit or Reason’ and maintained that ‘The political life of man is “a revelation of the Divine Idea’’’35 Green supports Hegel's idea that the state is supreme and source of all rights. However, despite similarity with Hegel, Green swings towards an individualist position and does not consider the state as an end itself. Unlike Hegel, the state becomes a means for an end, the end of ‘full moral development of the individual that compose it. The state in Green becomes a remover of obstacles that comes in the way of moral development of the individual. Previously, we discussed Green's idea of moral freedom that makes him a supporter of welfare state and positive liberalism. Unlike Hegel, Green does not demand unlimited political obligation and does not support that the state is an end in itself. Green's glaring difference with Hegel appears in his position that the individual may be justified in disobeying the state.

Primarily, Green does not justify resistance and treats the state as the sole source of right. He does not grant any right to disobey the law of the state merely on the ground that it runs against freedom of action of individuals. Green's Lectures on the Principles of Political Obligation, however, provide that resistance can be justified on social grounds. Green treats the state a provider of common good. For him ‘will, not force is the basis of the state’. This ‘will’ is general will, ‘common consciousness of a common good’ which people possess. This is ‘will for the State, not the will of the State.’ The State is obliged to provide common good, failing which it loses its claim. Further, Green though treats the state as the source of rights; he feels that human beings carry certain claims by virtue of their very human personality. These claims are ideal or moral claims and ought to be recognized by the state as rights.

Green presents a doctrine of conditional political obligation: Green's state is neither an end in itself, nor does it seek unlimited obligation based on force. Its claim to political obligation is subject to providing common good, recognizing the ideal rights of the people and removing the obstacles in the way of development of moral personality of the people. His Hegelian influence recognizes that one will never have the right to resist, but his individualist inclination concedes that one may be right in resisting. This means, one should be justified in disobeying the state only when certain conditions prevail. Wayper lists these conditions as ‘(a) if the legality of the command objected to is doubtful, (b) if there are no means of agitating for its repeal, (c) if the whole system of government is so bad, because it is so perverted by private interests that temporary anarchy is better than its continuance, or (d) if anarchy is unlikely to follow resistance, then only should the State be disobeyed.’36 In short, Green would support resistance and disobedience when it is obvious that within the existing circumstances full moral development is impossible. Unlike Green, Bentham would ask for political obligation on the basis of greatest happiness of the greatest number.

No political obligation and class struggle in a capitalist system: Marxian school endorses neither the view that the state is based on consent, nor that it can be a manifestation of a higher goal, nor an agency of common good. The state within a capitalist mode of production, or for that matter, state per se is an exploitative instrument. In a capitalist system, the state serves the purpose of the owners of the means of production. It is a class instrument and cannot claim for obligation from all. In a class divided society, there is no question of political obligation and the proletariat are engaged in class struggle against the exploitative class whose instrument the state is. Even in the socialist society after the proletarian revolution, when the state exists, it is under the dictatorship of the proletariat and again serves as a class instrument, though now in the hands of the majority. Marxian view provides no basis for political obligation. In fact, class struggle is a radical concept of resistance and revolution. Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin advocated such a position.

Consent through Hegemony: Neo-Marxian theoretician, Antonio Gramsci suggested that the state in the capitalist system deploys Hegemony for seeking consent of the proletariat. Hegemony refers to the ability of the ruling class to exercise power and ensure domination by seeking consent of those over whom it dominates. In his Prison Notebooks (written during his imprisonment) Gramsci analysed that educational (schools), cultural, religious (churches) and social (family) institutions create such conditions and generate such ideas in which the capitalist system is legitimized. Ideas, behaviour, customs, morality and social norms are propagated in such a way that they appear as what Gramsci calls ‘common sense, the philosophy of the masses. This means that the capitalist system legitimizes itself through cultural, ideological and intellectual domination. Legitimation and justification of the state in a class divided society is achieved through hegemony and domination. Hegemony is based on consent and not force, and is tacitly achieved.

Another concept, false consciousness, has also been employed by Marxian and neo-Marxian theoreticians to present how reality in a capitalist system is garbed through delusion and mystification to hide the exploitative character of the system. Marx, Engels and Lenin analysed this concept. Herbert Marcuse in his One-Dimension Man (1964) suggests that instead of ‘false consciousness’, as suggested by Marx and Engels, the term ‘false needs’ is more appropriate to capture the situation in a contemporary capitalist society. From this perspective, it appears that the capitalist state presents itself as if it is based on consent of the people, is capable of reconciling different interests and providing common welfare; though this cannot be the case in a class divided society. Hegemony and false consciousness are means that produce legitimation for the system.

Political obligation and legitimation crisis: As we have noted earlier that political obligation is related to legitimacy, i.e., if political obligation has to be forthcoming, legitimacy of the state and its institutions should not be in question. Focusing on the issue of legitimacy, some contemporary Neo-Marxian theorists such as Jurgen Habermas (The Legitimation Crisis), and Klaus Offe (Contradictions in the Welfare State), have discussed the concept of legitimacy in the capitalist and welfare states. The idea of legitimation crisis relates to the problem of political obligation. Both Habermas and Offe maintain that the state in capitalist societies is in a peculiar position where it has to maintain the condition of capital accumulation and free market (e.g., less taxation and less regulation by the state) as well as avoid social crisis and demand of an electorate (e.g., more taxation and public expenditure). In order to balance the two, there is always a legitimacy deficit on the one side or the other. As such, the state is caught in a crisis.37 Offe suggests that the state in a capitalist system is neither a negative state nor a neutral arbiter but only a protector of a set of institutions and social relationships necessary for domination of the capitalist class. What Habermas and Offe suggest is that a state caught in a legitimacy crisis may not command uniform political obligation or at least, may not have a lasting legitimacy for commanding political obligation.

Denial of political obligation: Anarchist, Gandhian and anti-colonial perspectives present a case of resistance and deny any political obligation. Anarchism treats state as an ‘unnecessary evil’ and seeks to abolish it. In an anarchist's view, there is no political obligation. Gandhi's view on state is that it is repository of brute force and must be resisted. His method of resistance is that of passive resistance and civil disobedience, same as Thoreau propagated in America against slavery during the 1860s. Obligation under colonial state is also denied. In fact, no duty to obey such a state, which is based on colonial domination and national subjugation, can be pleaded for.

Political obligation under political system framework: In political theory, concept of political obligation is linked with the concept of state and its authority. After the development of the concept of political system as model of analysis of political process, how do we locate the concept of political obligation? If we look at the definitions provided by Easton and Almond of political system, we find that binding, authoritative and legitimate force are the characteristics of the political system. Easton defines political system as ‘that system of interactions in any society through which binding or authoritative allocations (of values) are made’. Almond's definition of political system is also indicative of the same characteristics: political system ‘… performs the functions of integration and adaptation by means of the employment, or threat of employment of more or less legitimate physical compulsion …’ Given the binding or authoritative characteristic of political system and availability of threat of legitimate compulsion, political obligation or willing obedience is already assumed by both Easton and Almond. It appears that political system analysis does not seek any new ground or limit of political obligation than already sought by the theorists of the state.