3

A Doctor for All Seasons

Kavery Nambisan

A successful doctor has few inauspicious events to look back on. Criticism from a patient must rank as the worst of these. Dr Noshir Antia delighted in saying that the greatest gift he ever received was from a leprosy patient who threw a prosthetic shoe at him, saying it did not suit his needs. ‘I was pleased to have so well rehabilitated him that he could express himself without fear’. His other awards included the Padma Shri and the Hunterian Professorship, which the Royal College of Surgeons, London bestows on a choiced few from around the world.

N.H. Antia represented everything positive in our profession. Until his death on June 26, in Pune, at 85, he fought for the betterment of the poor and of medical methods. In surgery he strove for efficiency, scientific accuracy, flawless technique and dedication. As a plastic surgeon, he did reconstructive surgery that helped hundreds of leprosy and burns patients.

In the last few years he forged links with Bangladesh. A few weeks before his death, he visited the country for the 35th anniversary of a community health initiative he had worked with. He set up rural health projects in Maharashtra where many young doctors learned how to work and innovate in the villages.

Antia was also chiefly responsible for many of the pro-people healthcare decisions that were made by Indian Governments. Much as he abhorred politicians, he saw it as his duty to engage with them to make an equitable health policy a reality. He met Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, and other Ministers and bureaucrats, many times to influence the national agenda on health.

Meeting Dr Antia

I was lucky to have made his acquaintance five years ago. I introduced myself to him during lunch at a conference of rural surgeons. He asked me about myself and my work and then said, ‘Why don't you join me?’ That was his style: direct and uncluttered by formality. I did not join him, knowing I had the energy and boldness to attempt only a few of the things that he would want me to do. Every time we met, I was amazed by his vitality, his trenchant wit, his sharp grasp of current trends in medicine (and everything else) and his refusal to consider himself special.

Noshir Antia was born on February 8 1922, to Parsi parents, who lived in a small village near Hubli. He often talked with happiness about this period. ‘Not much money, no electricity and the bullock cart the only means of transport,’ he said. ‘But plenty of everything else’.

After school he went to Fergusson College, Pune, and the Government Medical College, Bombay. He won the Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons, London, and worked for nine years learning plastic and reconstructive surgery. He came back to work with Dr Coyajee in Pune, one of the best plastic surgeons in the country. Later he moved to the J.J. Group of Hospitals in Bombay and became the Head of the Tata Unit of Plastic Surgery in 1960.

At thirty-eight, he was young to be in such a senior position but he soon proved his leadership. He once told me how tough it was to change the mindset of doctors regarding leprosy. ‘When I started to admit my leprosy patients into general wards, the Hospital warned me that there would be a public outcry,’ he said. ‘But of course there wasn't. It was only the doctors who were afraid’. He had the courage to take risks, a virtue that is perhaps the hallmark of true leadership.

Importance of Research

Antia recognized the importance of research in medicine and set up the Foundation for Medical Research (FMR) in Bombay in 1974. A man remarkably free of pettiness, he made friends with all. He was greatly influenced by the educationist J.P. Naik and the activist Anna Hazare and often spoke of them with affection and gratitude. Of course, his greatest friend was his wife Arnie, a charming lady deeply interested in his ideas and projects. They were lucky enough to have had 50 years together. After his death, it was obvious that she was not going to waste time in grieving. She talked eagerly about the future prospects of the organisations he had set up and about his soon-to-be published autobiography. It was great good fortune that Dr Antia completed his memoirs a few months before he died.

What Antia managed to do in 27 years after retirement was remarkable. Having seen the need of rural areas and of the disadvantaged everywhere, he established many rural health projects in the Pune area that are models of their type. He was a great believer in the inherent strengths of rural women and his projects ensured that they were taught self-reliance. Under his supervision the Foundation for Research in Community Health (FRCH) served as the research secretariat for the Government's path-breaking Health For All project, which gave vision, shape and direction to primary health care in India. ‘There is India and there is Bharat,’ he said. ‘The India, which shines, has everything. Our work must be for Bharat, which has been ignored’.

He strove to make people aware of the Right to Information Act; he was one of the founding members of the Association of Rural Surgeons of India and served as one of its early Presidents; he trained scores of young doctors, health workers, social activists and researchers to take the common sense approach to health.

A year before his death, he handed over the stewardship of FRCH to a doctor who had started to work with him 35 years ago, Dr Nergis Mistry.

Dr Noshir Antia was a rare genius with a refined academic and emotional intelligence. I was saddened by the fact that one who did so much to make community health and preventive medicine a reality should die of malaria, a very preventable disease.

But, knowing him, I think he would have said, ‘Now there's a challenge. You do something that will help diagnose and eradicate malaria instead of writing about me’.

Vocabulary

- Inauspicious: Discouraging

- Abhor: Hate

- Uncluttered: Without unnecessary items

- Trenchant: Sharp

- Stewardship: An act of taking care of

- Eradicate: Wipe out

Reading Comprehension

- What criticism did Dr Antia receive from a patient?

- State Dr Antia's work profile in brief.

- What were some prestigious awards received by Dr Antia?

- What was Dr Antia's style of interaction?

- Enumerate some personality traits of Dr Antia.

- ‘There is India and there is Bharat. The India which shines has everything. Our work must be for Bharat, which has been ignored’. Explain.

Countable and Uncountable Nouns

Countable

Countable nouns are easy to recognize. They are things that we can count. For example: ‘pen’. We can count pens. We can have one, two, three or more pens. Here are some more countable nouns:

- dog, cat, animal, man, person

- bottle, box, litre

- coin, note, dollar

- cup, plate, fork

- table, chair, suitcase, bag

Countable nouns can be singular or plural:

- My dog is playing.

- My dogs are hungry.

We can use the indefinite article a/an with countable nouns:

- A dog is an animal.

When a countable noun is singular, we must use a word like a/the/my/this with it:

- I want an orange. (not I want orange.)

- Where is my bottle? (not Where is bottle?)

When a countable noun is plural, we can use it alone:

- I like oranges.

- Bottles can break.

Uncountable

Uncountable nouns are substances, concepts, etc. that we cannot divide into separate elements. We cannot ‘count’ them. For example, we cannot count ‘milk’. However, we can count ‘bottles of milk’ or ‘litres of milk’. Here are some more uncountable nouns:

- music, art, love, happiness

- advice, information, news

- furniture, luggage

- rice, sugar, butter, water

- electricity, gas, power

- money, currency

We usually treat uncountable nouns as singular. We use a singular verb. For example:

- This news is very important.

- Your luggage looks heavy.

Exercise

Change the following sentences into plural:

-

A teacher is sometimes strict to students.

-

A lesson is not always easy for learners.

-

A cricketer likes to play cricket.

-

My friend loves singing.

-

Furniture of this house is old.

Pronunciation: Silent Letters

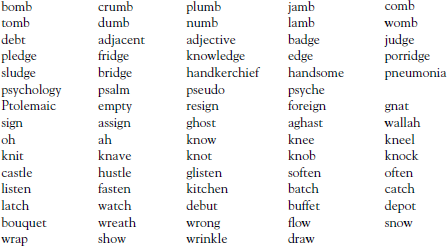

B is silent in a word when it is preceded by ‘m’ or followed by ‘t’ at the final position, e.g., in ‘climb’, ‘thumb’, ‘doubt’; d is silent in a word when it is followed by ‘j’ or ‘g’, e.g., in ‘adjust’, ‘adjoin’ and in some other words; k is silent in a word when it is followed by ‘n’ at the initial position, e.g., ‘knight’ ‘knife’; w is silent at the final position and it is also silent at the initial position when it is followed by ‘r’ or sometimes when followed by ‘h’, e.g., ‘wrong’, ‘write’, etc.

Practise speaking the following words with correct pronunciation. Find the letters which are silent in these words:

Writing

‘An angry patient threw a prosthetic shoe at Dr Antia, saying it did not suit his needs’. Considering yourself as the patient, narrate the experience describing Dr Antia's reaction to this criticism.