Introduction

With the announcement on January 27, 2010, of Apple’s iPad, and its support for the EPUB format, the world of electronic books, or ebooks for short, took a quantum leap into the future. According to IDPF (International Digital Publishing Forum), ebook sales in the U.S. in January and February of 2010 were $60.8 million, $5 million more than the entire fourth quarter of 2009 ($55 million). The iPad is not responsible for all of the excitement, but it sure isn’t hurting things.

This book is for people who want to create their own EPUBs, and publish them for the iPad in particular, but also on other ereaders, like the Barnes and Noble Nook, Sony Reader, and desktop ereaders like Ibis and Stanza.

In this chapter we’ll talk about:

• The differences and similarities among print books, ebooks and websites

• The EPUB format itself

• The size and structure of a page on the iPad

• Who this book was written for and where you can find updates, example code, and extras

Print vs. ebook vs. website

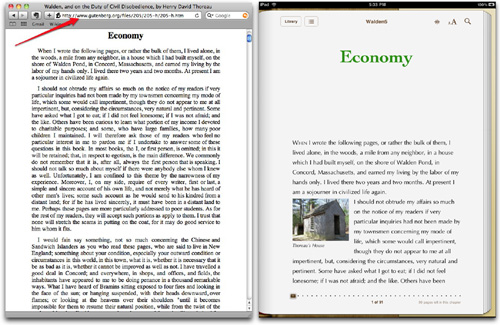

One of the first questions I thought about as I was writing this book was how an EPUB ebook was different from a website. Indeed, they have much in common. Both are written in (distinct but very similar flavors of) HTML and formatted with CSS, both adjust themselves to the constraints of the system in which they are viewed, and both are accessed electronically. Even their content might be similar; certainly there are websites (like Project Gutenberg) that make entire books available to readers. So what makes an ebook different?

The content is practically the same on the Gutenberg website (left) and the iBooks app on the iPad (right).

Another question that’s helpful to explore is what distinguishes an ebook from a print book. Again, there are many similarities, most notably in the content, but also in the idea of the page as a unit of information. Although with an ebook, this might be changed once, as a reader adjusts the font size, for example, it would stay the same throughout the rest of the reading experience. The reader could go back and know that the section in the upper left of the previous page would still be in that section on the upper left of the previous page.

I have outlined a number of areas where ebooks, print books, and websites, overlap and diverge, which I hope will be illustrative.

Static vs. Dynamic

One principal feature of ebooks and websites that is distinct from printed books is how quickly they can be changed and indeed are expected to be updated. It is understood that a website will be frequently updated, while ebooks might be updated occasionally, and regular books only before a new printing. It’s not only a question of correcting errors, or updating timely information, however. There is something about the static nature of a book that somehow gives it more solidness, more integrity. We judge a book, even an ebook, as a discrete collection of information, not as an ever-changing one.

Appearance

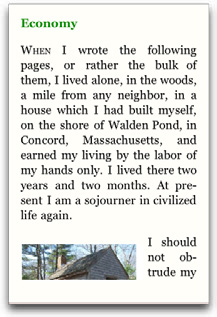

A printed book cannot change its appearance, although publishers sometimes offer various renditions of the same book: hard cover, paperback, large print, and so on. A single version of an ebook, however, can generally be modified by the reader to their own taste, by changing the font, text size, and sometimes even the color of the text and/or background. Although it’s also possible for users to change the appearance of a website (perhaps by choosing a custom style sheet or increasing the font size), it’s not nearly as widespread—or expected—as with an ebook.

A reader might choose a different size or font in which to read the ebook. This is, of course, unheard of for a printed book.

How it’s read

Printed books are generally read left-to-right or right-to-left. Websites tend to scroll up and down. Currently, many ebooks mimic the behavior of print books, surely in an attempt to make the transition to ebooks less uncomfortable for readers, who are accustomed to having a discrete amount of information on a page that doesn’t change size or shape.

One of the cool things about an ebook is that it reflows to fit the size of the device in which it is being read. If you’re reading it on an iPhone, the width of the page is a fair bit smaller than if you’re reading it on an iPad, or on some other reader. The beauty of EPUB is that it flows the text to fit whatever screen it’s on.

Here is the same file from the last few illustrations shown in Stanza on the iPhone.

This is different from a zoom function, that might let you magnify one area of a page, but doesn’t flow the entire page to fit. With zoom, you can get the text big enough to read, but then it’s a nuisance to navigate from one page to the next.

The order of things

With a printed book, you’re used to opening up the cover, leafing through a title page, copyright, table of contents, dedication, and even a preface before diving into the main content of a book. With an ebook, the book designer can control where you start reading. The first time you open an ebook, you might be thrust onto the first page of the content (if the designer thinks you’ll be annoyed by front matter). In this respect, ebooks are more similar to websites.

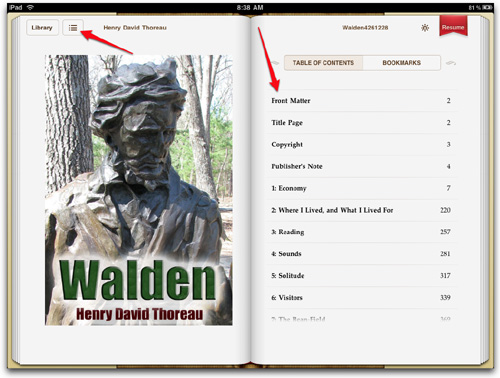

In a print book, you can often, but not always, consult a table of contents and then jump to a desired section. In ebooks (and websites), not only can you access the table of contents from any page, you often will find links in the text that transport you to other sections of the book, or even to related external websites.

Formats, durability, and batteries

Print books don’t become obsolete, don’t need batteries, and can be read in many different environments—including on a beach where sunlight and sand might make ereader devices less advantageous. They do require external illumination, however, if you’re using them in the dark, something which some readers, including the iPad and iPhone, do not. Books are more sturdy than ereaders, and don’t break when dropped or if they slip off the bed. And they certainly require a lot less outlay at the outset.

Searchability

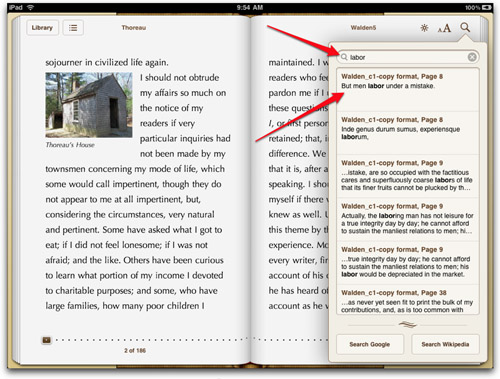

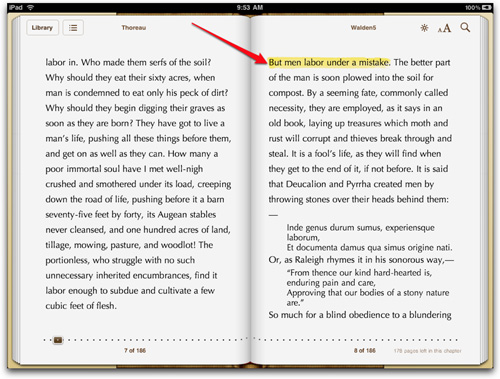

A printed book’s main search tools are a table of contents and an index, though the latter are only prevalent in nonfiction books. Most ereaders, however, offer some sort of electronic search of the full-text content of the ebook, in addition to a navigable table of contents, and less commonly, an index whose entries are linked to the referenced sections. Web browsers, too, commonly offer full-text search. Search, however, should not be seen as a reasonable substitute for a targeted index.

In iBooks on the iPad (and most other ereaders), you can search for words within your book and then click the found text to jump directly to that passage.

The table of contents in an ebook is navigable: if you click one of the entries, you automatically jump to the selected section.

Highlighting and sharing passages

Of course, one of the most popular things to do with any kind of book is share it. A printed book doesn’t have any special tools for allowing highlighting and sharing, apart from being open to pencils and highlighters and to being handed to friends. The ability to highlight and share an ebook depends on the ereader’s capacities.

Some ereaders, like the iPad, allow you to highlight a passage for future reference, but have no sharing abilities at all. Indeed, you can’t even copy a passage!

You can highlight text in the iPad (by selecting the text, and choosing bookmark) for later reference.

Others, like Kindle, let you create both notes and highlights, that you can view either in the book itself or online. Currently, the most highlighted passages in Kindle books are published on Amazon’s site, but personal notes and highlights are not yet shared among readers. The Barnes and Noble Nook lets you share entire books with friends, though you’re currently only allowed to share a particular book one time and with one person.

There are many tools for copying and sharing passages from websites. Indeed, there are tools for including chunks of a website in a different site altogether.

Copy protection

The EPUB format allows for DRM (Digital Rights Management) encryption so that the file can be read in only one specific kind of ereader and only by authorized users. It’s a shame, because while EPUB itself is very widely supported, the DRM severely limits that versatility, while it makes it much more difficult for the licensed reader to access the content, which they have come by legally. For example, if you buy a book through iBooks on the iPad, the added DRM will impede you from reading the book on the Sony Reader, B&N Nook, or even Stanza, even though they all support EPUB. Printed books have no such DRM. Websites don’t have DRM as such though some are located behind firewalls or subscription services.

Buying new books

While print books have long had advertisements and excerpts from sequels or other related books that publishers hoped people would buy, ebooks can contain direct links to bookstores that facilitate the immediate purchase of another ebook. On the iPad, readers can access Apple’s iBookstore from within the iBooks app. Ebooks can also contain links to external websites and other sources of marketing and information in order to generate additional sales. Websites can have links to other websites as well as to ebooks in all the various ebook stores.

What is EPUB?

The most widely accepted format for ebooks today is EPUB, which is developed and maintained by the IDPF. You can find the official specifications for EPUB documents on its website: www.idpf.org under, well, Specifications.

An EPUB document is a specially constructed zip file with the .epub extension. An ereader can reflow the content of an EPUB document into any size display screen, from a phone to a desktop monitor. EPUB also allows for the generation of a navigational table of contents.

The content of a book formatted with EPUB is contained in XHTML and CSS files, which may reference images and embedded fonts, and be encrypted with DRM. XHTML is a special flavor of HTML, which is the language that all web pages are written in. The EPUB file also contains a series of XML files that help format the book so that it can be properly read by an ereader.

There are a number of tools that can generate EPUB files for you, either from plain text, from XHTML, from Microsoft Word, or even from Adobe InDesign. Still, in these early days when EPUB tools are less than perfect, it’s a good idea to know what’s going on under the hood so that you can go in and make necessary adjustments. For example, Word doesn’t export drop caps, but you can edit the XHTML files by hand to allow them. InDesign doesn’t export text wrap with its EPUB documents, but you can set up the files so that a quick edit to the XHTML achieves that aim. In the rest of this book, I’ll show you both how to use available tools, and how to handcode extra features.

Navigating a sea of ereaders

There are a number of reader applications, or ereaders, that can read EPUB documents. iBooks on the iPad, Barnes & Noble Nook, and the Sony Reader support EPUB, as do Adobe Digital Editions, Lucidor, and Stanza (on various platforms), Ibis Reader (which is web-based), Mobipocket on Blackberry and Aldiko on Android, and many more.

The most well-known ereader that does not support EPUB is Amazon’s Kindle. I suspect that may change as more and more ereaders join forces behind EPUB, but only time will tell.

Unfortunately, not every ereader reads and interprets EPUBs in exactly the same way. Because the earliest popular ereaders (like Stanza) did not support any formatting at all, later ereaders felt forced to compensate by adding default formatting of their own and ignoring the formatting of the EPUB documents they displayed.

As EPUB designers have gotten more savvy, however, they have chafed under the sometimes overbearing nature of these ereaders, who instead of following the standards laid out in the EPUB specs, insist on overriding EPUB designs to make up for old issues. Ebook designers are discouraged from even choosing the font for their book—something a print book designer would never stand for—in the supposed interest of a good user experience.

Personally, I fail to see how properly designing a book takes away from a good user experience. Quite the contrary. Instead, in this book, I encourage you to follow the standards laid out in the EPUB specifications and to speak up for standards support in all ereaders.

Anatomy of an iBooks page

While this book explains how to create standard EPUB documents, it is also particularly focused on how to take best advantage of these standard features to make beautiful ebooks on the Apple iPad.

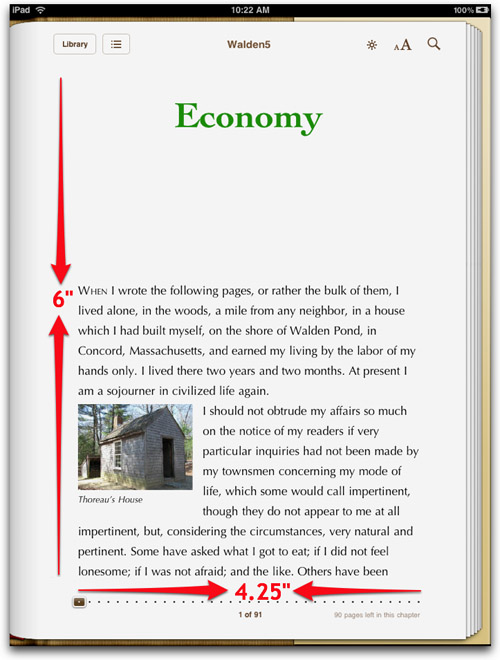

The iPad displays ebooks in two sizes: a single large page if you hold the iPad vertically and a spread of two smaller pages if you rotate the display to a horizontal orientation.

The size of the single vertical page is about 5.5 × 7.5″ (about 15 × 19 cm), although a fair bit of that space is taken up with navigation tools and margins, leaving a content frame of about 4.25 × 6″ (11 × 15 cm).

When rotated vertically, iBooks displays a single page of the ebook.

If you rotate the iPad to a horizontal orientation, you get two vertically oriented pages, each of which measures about 3.75 × 5.5″ (10 × 14 cm), which, when you take away the navigation buttons and margins, leaves you with a content area about 3 × 4″ (7.5 × 10 cm).

When rotated vertically, iBooks on the iPad shows two smaller vertically oriented pages.

The resolution of the iPad is 132 dpi, which is considerably higher than the average 98 dpi of a desktop monitor. This means that text and images will be physically smaller on the iPad, although they may seem about the same size since everything will be in proportion. If you call for text at 16 pixels, the iPad will display it at 16/132 pixels, which is about .12″ or about 9 points. Curiously, if you specify a size of 12 points, it will also be displayed at 16 pixels or 9 actual points. So much for absolute measurements.

The iPad displays text in Palatino, by default, but the reader can also choose Baskerville, Cochin, Times New Roman, Verdana, and Georgia. All but Verdana are serif fonts. The reader can also choose from 10 different font sizes, with size 4 being the default.

The iBooks application does not yet support embedded fonts, even though the iPad itself does (for example, in Safari), as long as these are in SVG format. One might presume that iBooks will support embedded SVG formats as well at some point.

The iPad does have a number of system fonts that can be used in ebooks viewed both on Safari and in the iBooks application. I will show you what fonts are available and how to call them in “Fonts in your ebook” in Chapter 4.

Who is this book for?

This book is for anyone who wants to publish an ebook in EPUB format, particularly on the iPad, but for any ereader that supports EPUB, including the Sony Reader, Barnes & Noble Nook, Ibis Reader, and Stanza. It explains how to use Word and InDesign—software you may already own and which might already contain your formatted books—to generate the files necessary that make up the EPUB, as well as how to manually create or improve the files in order to take advantage of the capabilities of the most advanced ereaders, without leaving underperforming ereaders too far behind. I believe strongly in following standards so that a book that works today will continue to work tomorrow in the next new ereader that comes along.

You don’t need to have either Word or InDesign to create an EPUB document; it is very possible to write the files by hand. Nevertheless, these tools facilitate the creation of an EPUB, and take advantage of the formatted documents you may already have created with those programs.

It is essential to have a good text editor so that you can adjust and adapt the files once they are created. I provide details and recommendations in the corresponding sections.

Finally, it’s very helpful if you have some knowledge of XHTML and CSS, since that’s what EPUB is based on and I don’t discuss XHTML or CSS basics much at all. If you are not familiar with HTML, XHTML, or CSS, I recommend taking a look at my bestselling HTML, XHTML, and CSS: Visual QuickStart Guide, 6th edition, also published by Peachpit Press. Many of the same techniques for designing websites are also valid for designing ebooks.

I will be posting updates, errata, extras, and more information on my website: http://www.elizabethcastro.com/epub as well as on my blog, Pigs, Gourds, and Wikis (http://www.pigsgourdsandwikis.com).