Components of the Professionalism Model

. . . Professions show a pronounced . . . movement toward the rise of marketable expertise as a more or less exclusively important status element . . . The movement can be described as a movement from “social-trustee professionalism” to “expert professionalism” . . .

—Steven Brint1

Keywords

Business education, higher education, professionalism, precursors of professionalism, academic capitalism, autonomy, expertise, self-concept, social agency

Introduction

Scholars recognize the need to educate business students as future professionals in society. Brint, Friedson, and Khurana all advocated a tier of professionals who can become an informed force that can thwart government bureaucracy, narrow the gap between capitalists and labor, and advance society as a whole. Professionals are supposed to be guardians of knowledge, while serving societal goals and interests.2 Friedson describes the ideal type of professional training by stating that:

Professional training . . . is not merely practical in substance. Above all, the ideology supporting professional training emphasizes theory and abstract concepts . . . . Whatever practitioners must do at work may require extensive exercise of discretionary judgment rather than . . . routine application . . . of mechanical techniques.3

The institutional focus on teaching professional expertise to students may have contributed to professionals becoming mechanical participants in their professional jobs. The aim of this book is to help develop professionals who are able to engage in business institutions by providing their knowledge, and yet be able to question authority, exercise autonomous judgment, understand broader societal goals, and perform their jobs as professionals without sacrificing their professional identity.

Prior Studies on Professionalism

In order to understand how to educate business students within a model of professionalism, we explore a number of prior studies. These studies, which include a number of professions, show that professional characteristics can be statistically measured in ways that signify strengths and weaknesses. Thus, we propose that colleges and universities, especially those with a business administration program, use the research and findings to target the weaknesses identified in preprofessional business students, and engage them in continuous professional development as part of the major.

Many of the scholarly works provide detailed definitions of the elements that have been used to define the professions. These include (a) belief in service to public; (b) belief in self-regulation; (c) sense of calling to the field; (d) feeling of autonomy; and (e) professional organizations as a source of authority (Figures. 2.1 and 2.2). Hall used a 50-item instrument known as Hall’s Professionalism Scale. He compared and ranked different professionals in accounting, advertising, law, engineering, medicine, business, and social work. Hall’s studies focused on the structural and attitudinal facets of professionalization that influenced the strength of professional values. He wanted to assess whether there was a link between the strength of professional attitudes and socialization that took place in the work environment. Hall indicated an inverse relationship between bureaucratization and professionalism. An increase in bureaucracy in the workplace resulted in employees achieving lower scores on the professionalism scale. Hall attributed these results to employees’ loss of autonomy due to the established hierarchy in the work environment that reduced employees’ decision-making ability. This was an important finding due to the presence of a formal organizational structure in most businesses.4

Figure 2.1 Professionalism Model (Hall Model)

Figure 2.2 Professionalism Model (Haywood-Farmer and Stuart Model)

Haywood-Farmer and Stuart’s study examined professional values.5 They developed an instrument to measure the degree of professionalism within medical services professionals (Figure 2.2). Haywood-Farmer and Stuart used an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) to test an instrument that measured the following scales of professionalism: (a) job autonomy; (b) societal role and impact; (c) expertise; (d) self-confidence; and (e) feeling of superiority. They found that the dimensions generated by the full model were more useful to assess the degree of professionalism than individual components, such as expertise or autonomy.

Several professionalism studies conducted in the nursing profession examined the dimensions of nurses’ general self-concept in connection with their profession.6 Cowin used factor analysis to identify the following dimensions of professional self-concept: (a) a nurse’s general self-esteem; (b) empathetic support given to another; (c) communications, defined as effectively sharing information and ideas; (d) knowledge using nursing skills and theories; (e) staff relations such as collegial relationships; and (f) leadership.7 Most of these dimensions of “self-concept” were used again in Nino’s study that is discussed below.

As mentioned above, several researchers studied professionalism in various fields. The prior studies highlighted the importance of studying the multi-faceted area of professionalism to better understand the dimensionality and factors that have influenced this latent attribute.8 Additionally, the prior studies indicated that the scale of professionalism varied as a function of the organizational environment.9 As Hall reported, the higher the bureaucracy in the organizational environment, the lower the professionalism factor-score.

The previous review of studies on professionalism guided Nino’s study of senior-level business students and the precursors of professionalism they manifested. This study focuses on the precursors of professionalism for senior-level undergraduate students. The attitudes and values that students hold at the beginning of their work-life is likely to influence the type of professionals they become later in their careers.10 The model in Figure 2.3 provides a lens to examine the promise of education—as scholars in education and ethics intended it—by exploring the professional attitudes of senior-level undergraduate students, immediately before they join the workforce.11

Figure 2.3 Professionalism Model (Nino Model)

The conceptual basis for this study included the components of professionalism identified in prior research.12 The graphic models for these studies, were presented before (see Figures. 2.1 to 2.3). The following are definitions of each element of the professional framework used in this study.

Autonomy of Judgment

Professional autonomy was defined as the practice of independent judgment guided by special knowledge.13 The professional autonomy of the subjects was measured by their ability to make independent decisions given their expertise, with the guidance of professional associations.14 This association provided the professionals with an authoritative source of reference for the rules and regulations of the profession.15 Several scholars referred to the concept of professional autonomy in reference to many professions such as law, medicine, and accounting.16

Expertise

Expertise was determined to be a vital component of professionalism since it represents the foundational knowledge that justifies the reason for the profession.17 Professional expertise was also found to be the core of professionals’ economic assets that distinguishes them from other social classes.18

Self-concept

Arthur and Cowin suggested that “self-concept” was a key measure for professionalism since it is an attribute that professionals developed with their expertise in the profession.19 It measured professionals’ self-confidence in verbal, written expression, and leadership ability. The special knowledge that professionals attained provided them with a feeling of superiority over others.20 Self-concept was also associated with higher intellectual and social self-concept ratings. 21

A foundational component of professionalism has been the strong ideological and ethical component that professionals developed.22 Friedson defined this component as “claim a devotion to a transcendent value which infuses its specialization with a larger and putatively higher goal which may reach beyond that of those they are supposed to serve.”23 This definition which encompassed “a belief in service to the public” dictated that the work performed by the professional will benefit both the public and the practitioner.24 This component was later renamed in Nino’s study as “Social Agency” which is a term used by the Higher Education Research Institute at UCLA for essentially the same meaning of this category.

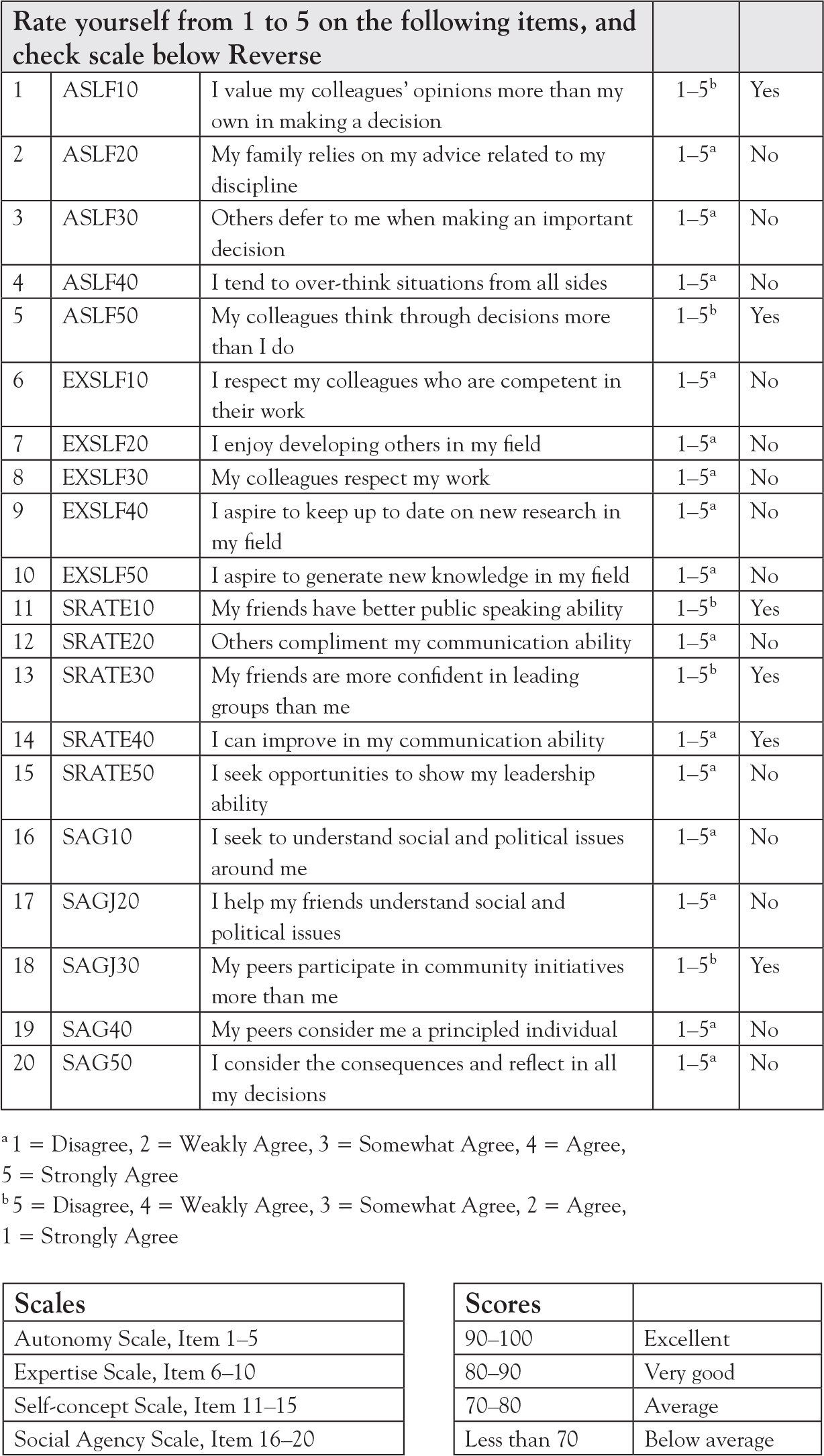

Another study on professionalism was done by the co-author of this book. In this recent study, Nino tested the “precursors of professionalism” of business students as specified in the prior literature. Nino employed the term “precursors of professionalism” since business students have not joined the profession, so the attributes only measured the “precursors” of these preprofessionals. To learn more about business students, this study used prior theoretical frameworks to model the precursors of professionalism—autonomy of judgment, desire for expertise, self-concept, and social agency. The study used data from the College Senior Survey (CSS) collected by the Higher Education Research Institute (HERI) at UCLA for two academic years from 2006 to 2008. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the four factors—autonomy of judgment, desire for expertise, self-concept, and social agency—indeed fit a cohesive model for the latent construct “precursors of professionalism.” The items that made up the four factors in this study are detailed in Table 2.1 below. The results of subsequent analysis of variance of the factor scores indicated that there are significant differences for most of the pairwise comparisons between business students and students from other majors. Below is a more detailed explanation of the results of the study.

Autonomy of Judgment Results

The results of the study show that business students, who comprise 17 percent of the sample, have higher factor scores than 43 percent of their peers in college, but lower than 40 percent of their other peers, after adjusting for gender and institutional differences. These scores of business students as a group are not significantly different from those who are nonbusiness majors and a more sensitive test may need to be developed in this category in the future. Yet, based on the numerical ranking, this finding suggests that business education may need more emphasis on students’ critical thinking skills, which may strengthen students’ autonomy.

Table 2.1 Measured Variables Used in This Study

The results of the study show that business students are the highest-ranking group—based on mean “desire for expertise” factor scores—among all majors after adjusting the marginal means for the covariates in the study. Additionally, scores of business students, as a group, are significantly different from nonbusiness majors. This finding suggests that business students are highly motivated to develop the business expertise necessary to enter their profession, especially since the profession offers high financial rewards for managers and executives working for corporations that are highly profitable .25 Other scholars have discussed the hidden language in business education, emphasizing the corporate bottom-line and the success of managers in businesses.26 This emphasis resulted in higher salaries for students, since this applied knowledge was responsive to corporate needs. These higher financial rewards may have caused business students to place high emphasis on attaining expertise in the profession.

Self-concept Results

The results show that business students who comprise 17 percent of the sample have higher factor scores than 74 percent of their peers in college, but lower than 9 percent of their other peers, after adjusting for gender and institutional covariates. Additionally, scores of business students, as a group, are significantly different from nonbusiness majors. This finding suggests that business education may have more emphasis on students’ leadership abilities, which correlates to students’ self-concept, as compared to most other majors. This was confirmed again by a study performed by the Graduate Management Admission Council (GMAC) of employers regarding their hiring practices that consisted of 1,509 participants representing 905 companies in 51 countries. Most employers reported that business students have higher abilities in motivation, and learning, when compared with other employees at the same job.27

Social Agency Results

The results of the study show that business students who comprise 17 percent of the sample score lower in their factor scores than 71 percent of their peers in college but higher than 12 percent of other peers in “social agency” scores, after adjusting for gender and institutional type. Additionally, scores of business students, as a group, are significantly different from nonbusiness majors. This finding suggests that business education has a lower emphasis on ethical and social issues in their education, as discussed by prior scholars.28 Business students rank in the same grouping as technical majors—such as engineering, math, and physical sciences—in mean factor scores of social agency. This is another piece of evidence that students are being educated in a manner similar to those in technical fields, such as physicists, engineers, and others. The business curriculum’s emphasis on accounting, finance, marketing, economics, and statistics does not leave much room for meaningful integration of other disciplines.29 Although it continues to be necessary to provide technical training to business students, in order to meet corporate needs, it is highly urgent to recognize that business students become managers of organizations, where their decisions have societal consequences. Therefore, their future roles in business should influence the direction of their education.30

Institutional and Environmental Factors

It is likely that students who majored in business arrived at their college or university predisposed to a focus on developing expertise and had little interest in contributing to their community and society. Additionally, students’ choice of major and the norms within the business departments where students enroll might, in turn, support and nurture their natural tendencies, thereby increasing the likelihood that business students will achieve the above results in their precursors of professionalism. Higher Education scholars argue that academic environments can differentially reward and reinforce students’ varying interests and abilities.31

Some evidence suggests that academic majors differentially shape students’ attitudes, interests, and abilities. Smart and his colleagues provide the most convincing evidence that academic environments differentially reward and reinforce different interests and abilities, accentuating initial differences. The changes in students’ abilities and interests are greatest when students enter an academic environment congruent with their initial interests. (p. 326)

Business students may select the major based on their initial interest and abilities in the subject matter, but the major’s academic environment can accentuate these initial differences in students. The results in the precursors of professionalism may have been due to students’ initial interests in business expertise as well as their natural abilities in leadership; yet the academic environment that was congruent with students’ interest may have accentuated the students’ results.

In summary, the results of the study on precursors of professionalism show great promise in the development of business students’ professional acumen or expertise, but also some deficiency in other areas of the professionalism scale such as autonomy and social agency. This result may influence decisions and actions of future business managers and their promise to develop fully as professionals. The implications of this study call for a more in-depth use of the professional framework in the education of business students.

Implications of the Study

The implications of the results in this study are important to business education and the business profession. Compared to their peers—especially those who are in other social science fields—business students score higher than most in the areas of their “desire for expertise” and “self-concept” and lower in “social agency.” Students’ results in “desire for expertise” and “self-concept” show great promise in the development of their skills toward professionalism. These students are excited about their fields of discipline as shown by their high scores in the “desire for expertise” factor. They also have confidence and strong self-concept to succeed in their field as shown by their scores in the “self-concept” factor. Yet, their lower scores in “social agency” reveal that business students may be deficient in their promise to develop as full professionals. As previously noted, this study did not examine the predictors that influence their scores, such as precollegiate individual characteristics, experiences, and programs students joined in college, internships, parental attitudes, economic status of students, academic ability, and a myriad of other factors that may influence these precursors.

Importantly, this study shows that students’ major of study is a significant factor for students’ scores, and that business students have low scores as compared to their peers in some areas related to professionalism. Moreover, Khurana, Swanson and Frederick, Trank and Rynes all point to the deficiencies in business education when it comes to integration of ethics and awareness of social issues within the business curriculum.32 The theoretical framework on hidden curriculum, used in this study, may also explain business students’ lower scores in “social agency.” The overemphasis of the business curriculum on duties to shareholders rather than stakeholders may have influenced students’ social agency. Colby et al. called for the overhaul of business education.33 These scholars proposed strategies for curriculum, teaching methods, and program arrangements that can transform undergraduate business education into a discipline that graduates socially-conscious professionals. Additionally, Colby et al. explain that the goal of education is to develop and graduate students who have capabilities in the area of analytical reasoning, the ability and disposition to take multiple perspectives when confronting a complex decision or judgment, and the capacity to make connections of personal meaning between what one does and who one intends to become.34 All of these characteristics allow students to develop a professional identity. This is likely where business education fails, namely, in the formation of a complete professional identity where students are able to integrate their expertise with autonomy and social responsibility.

New Directions for Business Education

Along the lines of Colby et al. in “Rethinking Undergraduate Business Education,” this book calls for integrative learning for students, which requires institutional intentionality.35 This integrative learning suggests weaving liberal arts subjects with business subjects. The result does not occur by merely adding a humanities or science requirement to business.

This book calls for a set of courses and teaching methods that require students to make thoughtful, well-informed choices about their future in business and recognize how their business roles will affect the meaning of their lives and the kinds of people they become. The process we suggest conforms to Kohlberg’s theoretical framework that is based on moral development through stages of maturation.36 Doing so will support business students in their development of critical thinking and ethical evaluation modeling during the 4 years of college. Business programs should aim for students to develop a conceptual vocabulary for thinking and talking about ethical issues and choices. Having a series of business program courses that offer theoretical and integrated experiences certainly requires more than just distribution requirements within a program. The courses should build on one another and add up to a powerfully integrated student experience. Its design has an intentional structure to provide a sound and responsible business education.

This study on the “Precursors of Professionalism” confirms the need for all business programs to adopt an approach to business education that incorporates the professional view and highlights the influence of this profession on society. We argue that this book will help students develop a full professional identity that is embedded with responsibilities, as well as expertise. This study confirms that our business graduates echo the weaknesses identified by prior scholars. This confirmation points to the need to revamp our educational methods to weave professional approaches into our current curriculum and methods of education. We recommend that educators start by helping students assess their facets of professionalism. A simple questionnaire is included in Table 2.2. The questionnaire can be used in a simplified numerical scale allowing the students to compare their score of one section to the others, thus identifying their strengths and weaknesses.

Table 2.2 Classroom Instrument

In the next chapter, we review other professions that have taken the journey from occupation to a profession, including medical and nursing professions. Both Chitty and Black in the nursing field, and Wear and Bickell in medical education, have made significant contributions to their fields in terms of professionalism.37 We argue that all methods suggested in their writing and those we suggest should be implemented with an eye on the traditional characteristics of professionals: autonomy of judgment, expertise, self-concept, and social agency. Importantly, in Chapter 3, we outline the curricular approaches that allow colleges and universities to develop business students in these professional dimensions. These curricular approaches include:

- A foundation of ethics with repeating themes

- Theory development orientation

- Multi-framing, critical thinking, and leadership

- Research and continuous knowledge building

- Community service orientation

- Adherence to a code of ethics and standards

- Professional organization participation

- Self-regulation and autonomy

We adopted most of these elements from the prior literature about weaving professionalism into preprofessional education. We explain them in a practical, implementable context allowing individual business faculty or business departments or schools to adopt them. We see this implementation as a continuing journey, rather than one action plan. We also view that any improvement faculty members make toward the development of better professionals is an important improvement for the future of our society.

Notes

1. Brint (1996), p. 203.

2. Brint (1996); Freidson (2001); Khurana (2007).

3. Freidson (2001).

4. Hall (1968).

5. Haywood-Farmer and Stuart (1990).

6. Cowin (2001); Hensel (2009).

7. Cowin (2001).

8. Cowin (2001); Haywood-Farmer and Stuart (1990).

9. Hall (1968).

11. Damon (2009); Kohlberg (1976); Pascarella and Terenzini (1991).

12. Cowin (2001); Hall (1968); Haywood-Farmer and Stuart (1990); Imse (1962).

13. Goode (1957); Moore and Rosenblum (1970).

14. Moore and Rosenblum (1970).

15. Freidson (1994).

16. Freidson (1984); Hall (1968).

17. Brint (1996); Freidson (1984).

18. MacDonald and Ritzer (1988).

19. Arthur (1995); Cowin (2001)

20. Haywood-Farmer and Stuart (1990).

21. Freidson (1984); MacDonald and Ritzer (1988).

22. Brint (1996).

23. Freidson (2001).

24. Goode (1957).

25. Crainer and Dearlove (1999); Khurana (2007).

26. Bowles and Gintis (1976).

27. General Management Aptitude Test (2011).

28. Khurana (2007); Swanson and Fisher (2009); Trank and Rynes (2003).

29. Bennis and O’Toole (2005); Khurana (2007).

30. Colby, Ehrlich, Sullivan, and Dolle (2011); Khurana (2007).

31. Terenzini and Pascarella (2005).

32. Swanson and Fredrick (2001); Khurana (2007); Trank and Rynes (2003).

33. Colby, Ehrlich, Sullivan, and Dolle (2011).

34. Colby, Ehrlich, Sullivan, and Dolle (2011).

35. Colby, Ehrlich, Sullivan, and Dolle (2011).

36. Kohlberg (1976).

37. Chitty and Black (2011); Wear and Bickel (2009).