2

Governance and Transformation

2.1 Governance at the university

2.1.1. Values and the “must be”

Georges Canguilhem, born in Castelnaudary in the Aude region of France, was a doctor and his philosophical thought was perpetually called upon from a practice, a vital experience, in terms of responsibility, requirements and tasks. His philosophy, as presented by Pierre Macherey, is that of a “must be”, of resistance, as opposed to the idea of being, of ontological necessity and of (a priori limiting) categories. He poses the central question of work and technology, of taking control of life, living conditions and the environment. To live is to risk, to risk yourself. Life is daring.

Between being and one’s must be, between necessities and demands, Canguilhem did not hesitate: he rejected identity (of self and of an environment), essence and necessity in order to be interested in axiological demands. He also did not hesitate to choose between technology as an applied science and technology as vital practical experience. Indeed, technology combines work, control and risk-taking against a backdrop of adventure and resistance, and turns the relationship between knowledge and action upside down. Negativity holds a structuring and decisive place: a position of otherness that makes negativity positive (since it is part of thinking and of the relationship with the environment), through the conflict of values. Life is a normative dynamic, an affirmation of polarities (and oppositions), and the scientific mind finds matter and stimulation in this, particularly in the questioning of what the environment is. The idea of otherness leads to the idea of alteration: to act, to think, to take part, is to be involved in processes of transformation and reconstruction of norms and frameworks of perception.

Canguilhem’s thought turns away from a positivist and scientist rationalism, and engages in a refocusing on an axiological subject according to the requirements of its own conatus. To live is to work, to know, to feel alive and to win “against”.

At the very heart of reality, values encourage it to become other; they are a forward-thinking, requiring it to be more or less what it is, guided by the possible. If values challenge the facts, it is not that they claim to be a substitute for them: they are not higher-level facts, but they regulate action. Values make people act, push us to act in reality, and are based on the gesture:

“Values, which are in conflict with each other more than they are with facts, are not possible ideals, rational forms awaiting their realization, which they would counterbalance.” (Macherey 2016)1

Thus, the philosopher sees in utopia a formidable spring, not in terms of a hovering and prophetic evocation of a future or of an alternative to reality, but as an internal dispute, a demand for surpassing, real in power, propulsivity:

“The facts under the appearances of which reality manifests itself are not, as we naively think, facts in a finished, static form, to be taken or left as such.

This is why true values, those that are able to set in motion a normative dynamic, are all without exception negative values; they represent the intrusion of the negative into the state of affairs that they call into question, and thus open up, in a climate of uncertainty and insecurity, the prospect of a future.”

As an advisor or project manager, this is how we proceed: monitoring on the lookout for deviations, routines, incessant vigilance with regard to the work of the experts, their appropriation of the principles, values, ethics and methods on which the evaluation approach is based, as well as with regard to what is opposed to it:

“The ‘I’ is not in the world in a seeing relationship, but in a surveillance relationship.”

Values polarize and regulate: they force us to identify a negative, to challenge it by affirming a positive, a sense of the possible. This negative leads to a position of otherness that should be interpreted in an affirmative manner rather than a defective manner:

“The call to values, far from being carried by a consensual spirit of reconciliation, fulfils above all a corrosive function of dispute. It was in this sense that Canguilhem interpreted the lesson of resistance that he had received from Cavaillès.”

Values are trends and styles, not imposed norms nor the preservation of an existing one. Immanent, they require imagination, creativity, normativity. They make the subject, a subject of action even more than of reason, persevering in its being. Identity can only be tendentious, tilting, exterritorializing. Mobility and displacement are a characteristic of the living subject, by its plasticity, the possibility of changing environment – internal environment, external environment – of inhabiting it as a space of possibilities, not according to the laws of an ontology, but according to the values of an axiology; an environment of problems:

“The relationship of the living being to its environment does not, therefore, have the character of an immutable fact, objectively given, but it is tendentious, in the process of being carried out, never completed; that is why its appearance is that of a must be whose fulfilment, subject to the conditions of precariousness, is not guaranteed.”

The ground for a practice is not given at the outset but is elaborated, constructed, emerges, happens, according to a watchful reflection on its possibilities. The subject aims to emerge. The practical relationship to life, while diving, as a body, is a matter of immanence: the subject is only one element among others in its environment. For all that, it judges, estimates, measures, negotiates, enters into conflict:

“To have to be, then, no longer means to impose by the force of one’s will alone new norms of existence in the direction of its enlargement, but to have to be, to continue to be, to persevere in one’s being, taking into account the multiple risks of disturbance caused by the errors of life and the uncertainties of the environment, both of which can neither be ignored nor countered head-on.”

It is the disease that is the truth of life, it is the pathological that is the truth of the normal, it is the failure that is the truth of success. We think of Foucault’s (2001) reflections on psychology, which is only saved by returning to hell. Indeed, we can consider that conflictuality supports action: by bringing to it and supporting it with a negativity, a shadow intrinsic to the human condition and to human action (in a way, irremediably doomed to fail), it offers the subject a position of otherness, the obligation to make choices, to polarize, to engage in a position that it conquers by this very movement of commitment. To live is to prefer and exclude.

So life is judgment and we would be wrong to believe that this judgment is intellectual, unless we consent to anthropocentrism – of which phallocentrism is one form, with an additional degree of reductionism. The philosopher drags us dynamically and reorients us on an axiological subject; they thus move away from the deterministic, objectivizing and neutralizing tendency, favored by a positivist and scientist rationalism. Life is plural manifestations: a plurality of human constructions and historical achievements.

More than substance, the human being is modality, style, polarity, they seek their own paces, their own requirements, between immanence and transcendence, relative and absolute, subjective and objective. Such is the scientific spirit:

“This effort, far from being the result of a break with the world of life which, once accomplished, would allow us to follow, from one achievement to the next, a progressive path that responds only to the needs of pure reasoning, moves forward only under the impulse of the conflict of values, through the confrontation with negative values, i.e. by constantly overcoming obstacles.”

This perspective, reflecting on the alternative between the substantial and the modal, is not only theoretical and cognitive, but above all pragmatic, experiential, dependent on unforeseen confrontations, “strange and uncertain things”, whose triggering or irruption in life is not decided, is not controlled by the subject. The latter does not, however, close itself in or shut itself in: it wants to get to know them, or even provokes them by acting in one way or another. In doing so, it chooses, discerns and asserts preferences. The philosopher’s vision embraces the situation of amoebas and plants that also “think”: they make choices in practice, without the need to theorize them from a distance:

“Thinking therefore comes first, before reflecting, judging, orienting oneself, even if it means suffering the consequences of choices that can be, and often are, unfortunate and inappropriate. The ideas that accompany these spontaneous, primordial manifestations of thought, by which it comes down to preferring and/or excluding, are likely to be, as Spinoza would say, highly inadequate, which does not prevent them, if they are not able to be displayed and recognized as true ideas, from being true ideas.”

The relationship to the environment that Canguilhem’s thought provokes leads us to soften and broaden our definitions, and to integrate into our visions and our feelings the vitality of the non-necessarily human entities that surround us, their perseverance to exist, to create their environment and ours.

2.1.2. Investigate, diagnose

“And now our timeline becomes even more complex:

- – the first debate gave us the principle of the movement;

- – the second delivered the progression on the past-future axis (possibly enriched with hermeneutic reversibility);

- – the third stage crossed Kairos and Chronos and suggested the diagonal of the story;

- – now the fourth step suggests the spiral figure, or progression on both axes at the same time, by collective training and elevation to the next level.” (Ost 1997, p. 39)

The methodological choices of our work have progressively moved towards abductive and transductive approaches:

- – abductive (Hallée 2013) by focusing on the understanding of the genesis of certain processes, by going back in time (a research-archaeology);

- – transductive, in being sensitive to the issue of the sharing and dissemination of the trials, which are becoming increasingly widespread. A gesture of research is inserted into an ecosystem, produces individuations and individuates itself in contact with neighboring entities (see section 3.1).

The vision of abductive and transductive research moves away from the classical deductive, overhanging approach, making the epistemological break an essential attribute of the scientific approach.

These considerations are inseparable from our vision of the teacher-researcher’s profession, built up through experience in a context of professional teacher training, where the dissemination of research was concretely operationalized in specific systems and through co-piloted work programs, associating trainers of various profiles and managed in a collaborative spirit (as opposed to a top-down dissemination towards targets to be instructed).

It is therefore a question of moving towards a research more anchored in common sense2, of taking a direct interest in the lived situations as they appear and as they are said. This does not prevent distancing, which is essential for the work of thinking, but it does want to avoid posture effects. It is a question of initiating a movement, going from living contact with situations to the representation that the researcher makes of them and from which they work, a movement that aims at returning to their field of practice, now nourished by reflexive work.

Exchange, dialogue and spiral progress are the best ways to imagine the work of an involved research, a research in action. The challenge is to continue to train, to explore paths, to use the knowledge and resources that they constitute, to reflect on the movement that constitutes daily work (individual or collective achievements, project approaches, team training, reference to context and frameworks, mediation and translation of professional texts, attention to weak signals and invisible trials).

Team and project management is similar to the management of groups of pupils or students, or even to knowledge management, when it is a question of creating a work ecosystem, by being involved in it oneself, by creating a digital workspace (design of an ecosystem of problems and constraints) or by leading teams (methods, time scales, deadlines).

The advantage of the approach lies in the questions of development and transmission articulated at the level of the supervision and management of the university; the anthropological vision of work and the institutional context is articulated to questions of innovation, evaluation, professionalism, skills, mobility, career and reflexivity. The themes of transformation, modernization and Europeanization of the university (of the public service, its institutions and operators) are crucial. They raise questions of scale, of human and organizational development issues, they presuppose confidence and a taste for risk, they call for a knowledge economy in movement, in tension, in complex ecosystems, they require care for the immaterial and the living. They call for a clarification and prioritization of values for those who work, study, cooperate and seek.

Once again, the reference to older work is useful. We think in particular of Mary Parker Follett3, bringing her closer to the current notion of care: Follett sees the manager as a gardener who is attentive to what is growing, who observes initiatives, helps their development and aims to integrate conflicts. Conflict integration allows for a socio-cognitive and relational well-being that benefits all parties (as opposed to compromise and power relations, other modalities for dealing with conflict) and characterizes constructive leadership.

Let us illustrate using an example: on the occasion of the devolution of extended competences and responsibilities (application over five years of the LRU law of 2007), the university is reforming its budget organization chart; this ultra-technical work is entrusted to the financial affairs department, as well as requiring political support within the institution, in particular by the board of governors, which decides on the appropriateness and implementation of the approach. It is therefore necessary to accompany, support, explain and obtain approval for the approach; to translate it and make it understood, if necessary, that the reform wants to insist on a very specific vision of the organization of the university, of its positioning as an operator of the State. Beyond the technical and instrumental aspects (technology is useful, assists, is sometimes constrained), it is also a question of seeing how it extends the human, as a work, a configuration of actions made possible or necessary. It is a question of recognizing the tool as indispensable equipment for human work and its understanding.

In this way, we are interested in collaborative work techniques, and design in particular, as a means of cohesion, inventiveness and development. The design of public policies is a widespread tool in Northern European countries for collectively designing public action, including with users, thinking together about its implementation, organization, evaluation and continuous evolution. Even if design puts shape, image and representation into form, its object is elsewhere; it is in the quality of public action and in its ability to adjust.

A cycle of studies in economic development4 allows a group of about 60 auditors from the public and private professional worlds to participate annually:

- – to learn about territorial, economic and political issues, grasped in situ through theoretical perspectives on the major issues inherent in development (economic, ecological, societal);

- – to conduct thematic research in small groups (health, transport, energy, education) and to produce a prospective report;

- – to observe specific methods and cultures (e.g. the modernization and design of public policies in Denmark);

- – to deal with cultural issues relating in particular to the relationship with the State (in France, Switzerland, Denmark);

- – to explore the challenges of modernizing public policy in France and Europe (Ministry of the Economy) and the fundamentals of res publica, as seen from the perspective of the senior civil service.

This type of situational training allows us to understand the issues in terms of territorial development from different aspects, to identify the stakes, to seek to equip ourselves to act appropriately (as far as we are concerned within the public service of higher education within a wider ecosystem).

Although, in the field, the players are not lacking in involvement in seeking to innovate and evaluate their achievements, initiatives nevertheless remain local, as underlined by the Agence nouvelle des solidarités actives (ANSA 2014; France stratégie 2016): not capitalized, they do not inform the more macro levels where decisions are taken. Public action proves to be vague, overly based on fragmented voluntarism and lacking in strength and rationality. This is a serious problem in terms of political legitimacy and the intelligence of work, at the societal level (dissemination, exchanges, changes) as well as at the intermediate level (analysis of human activity, capacity to formalize it, to stimulate it, to supervise it pertinently).

In the management of public affairs, there is a recurrent lack of discernment, confusion between what can be done and what is necessary, leading to overly optimistic projections of uncontrolled factors, and silence about the factors that can be influenced (this also concerns the functioning of an institution of higher education, its limited resources and its weak culture of internal control of its activities). In this sense, it is highly regrettable that acts of management, organization and supervision are devalued, trivialized, leveled and entrenched. We should try to shift the relationship to tools and technology, bearing in mind that tools take the form that we give them: through the use that is made of them, they inform themselves and us.

These questions are developed by work on organizational learning (Argyris and Schön 2001; Bouvier 2007; Mallet 2007) or within the Institute for Sustainable Work and Management (Itmd), particularly around the notion of learning work, which is part of the theoretical line of thinkers such as Clot (2006) – but which, it can be noted, has not focused its analyses or questions on the university.

2.1.2.1. The feminine, an added value

The question of women, their investment and added value in the dynamics of work, supervision and implementation of public policies, has not been explored much to date. However, for the sake of a world to be renewed, the rise of the feminine as an outsider and the injunction to “do better than her fathers”5 demonstrate offensive and reflexive qualities (combativeness, audacity, mètis) and original performances (volte-face, reversal of stigmas, clandestinity-advertising). Their irruption into fields (professional, political, civic) largely and historically dominated by men leads women to build a specific performance space, a robust capacity to act and a poetic speech that undoes certain modes of relationship to truth (Irigaray 1991), an embodiment to change them from within. They are building a normativity independent of community and media ambiences that have long been accustomed to going beyond their word.

It now turns out that collective intelligence is not correlated with the individual intelligences of the group’s stakeholders, but is more specifically due to three factors: the level of social sensitivity of each group member, the balanced distribution of speakers and the proportion of women – the more women there are in the group, the better the group performs (Woolley et al. 2010).

The capacity of the feminine to integrate in complex sets the constraints emanating from inter-individual links (Gilligan 1982)6 produces a rationality qualified as care, ethical gesture, thought in action, situated cognition. Care is anchored in the contextual and relational constraints of situations and preserves the quality of links in a world of interdependence. It is the way in which problems are constructed that is indicative of this alternative voice, the antipodes of a hegemonic position of expertise or princely overhang. It can lead to a distancing from the effects of authority and power, when they are not in line with what women know to be true by experience and which they are capable of objectifying (Bouissou 2015):

“The heroes of fairy tales are called upon to face challenges from which they emerge as winners, if and only if they place themselves outside the system of power relations, they enter into another order of relationships.” (Muraro 2004, p. 134)

This is the challenge for women today, when they are able to engage socially and professionally, when they have a sufficient level of education to analyze and distance themselves from power relations and assert their position in the social field. Many women are developing a strong taste for accompanying the work of others, aware of their role in mediating and confronting the various receptions of the world; the watchword: to make viable new ways of collective existence and work. The function of sorority, reciprocal mothering, affidamento (relationship of trust, mutual aid, cocooning) in women’s groups is essential:

“It is mediation and distancing that women still need.” (Irigaray 1992, p. 17)

The challenge is therefore an effort to change the cultural atmosphere, to shift the questions, to transform oneself from within into knowledge and social skills, to pay attention to qualitative differences, to strengthen subjectivity, to recognize the importance of the symbolic, to emancipate oneself from logocracies (Prokhoris 2002; Steiner 2003).

Inheriting knowledge structured via the masculine form does not prevent us from using it by putting a new wisdom at the service of the common good, observing social organizations, studying their genesis, taking a singular critical look at them, and committing ourselves to them by redefining the normative frameworks (Woolley et al. 2010, 2015; Citizen Today 2013). Women also inherit a thought that has been formed through centuries of silence, meditation and mediation, thoughts dependent on life, confrontation with bodies, with others, with the bodies of others (Woolf 2012). They also inherit a few elders who have been able to speak out politically and civically, based on their own personal experiences. Welcoming otherness and making something of it for oneself and for the other is specific to psychic bisexuality and female genius, identified by Kristeva (2003) – and not only for women.

The feminine can interfere in everything: when it does, new ecologies are formed, irrigating the intimate and the political, asserting a civil responsibility as close as possible to the situations, problems and conditions of their expertise. Follett’s (1924) intuitions are inspiring sources: as a pioneer of “gardened” management7, she worked as a consultant and social worker to renew the organization of living together, making conflict an integrating factor rather than antagonisms and divisions, thinking power with rather than against.

The capacity of the feminine to take oneself in hand (alone or with others) leads to the formation of rationality tinged with moral imagination, inspired by the return to the primordial childhood of beings and things, as a return to meaning: the interior is exteriorized, the pre-individual is individuated, the reserve of potential is solicited for/by a new individuation. For this, tools are needed; design is one of them.

Bonhet (2016) provides interesting analyses of behavioral design as a tool for intervention in organizations, to transform them from the inside by focusing on the observation of current situations: simple gestures, which do not disturb the fundamentals of organizations, but nevertheless redirect flows by a better adjustment to values (e.g. that of equality between women and men). According to the economist, there is a third way (behavioral economics), between major programs and individual voluntarism.

2.1.3. Building in project mode, accountability and getting to know each other

In a university, management in project mode, integrating the central services (finance, budget, human resources, information system, quality unit), the elected councils and the components (research teams, department) ensures circulation, an understanding of the general circuit and the participation of everyone.

For example, the long-term work on the institution’s agreements with its partners (of which there are hundreds), their circuit, monitoring and implementation are aimed at making procedures more secure, lightening the burden on the various actors and services (legal, financial, IS, support functions) while enabling them to rethink their modes of action.

The implementation of cost accounting consists of describing the activity of the establishment (in an exhaustive manner and avoiding redundancies) according to major strategic axes. This type of project is traditionally carried out operationally by the financial controller. However, it is an interdisciplinary and multi-actor project, which cannot make sense if it is not integrated into a political vision (how do we define the institution’s activity?).

Starting from what exists, from the reality of the activity, which is highly abundant, complex, plural, lived and perceived by each person from their position, their problems, their needs, their preoccupations (and therefore at a level that is too local and specific to make sense at a general level), we seek to define the major sectors of activity that we wish to highlight, and according to what design and what organization.

This means translating in several directions: depending on what the policy wants (e.g. valuing and better recognition of teaching work, or valuing and publicizing the institution’s efforts in terms of student success, etc.) and on what it needs in concrete terms (e.g. to build a teacher timetable repository).

A distinction should be made between a budget organization chart based on the functional organization chart (departments, directorates) and an analytical organization chart:

- – the functional organization chart allows us to visualize the establishment from its components: it is quite intuitive and corresponds to the spontaneous way of considering an organization by its direct users (places and people);

- – the analytical organization chart supposes a shift or even a conversion of the gaze by extricating itself from “who and where” representations to thinking in terms of “what and how”, aimed at ordinary citizens, that is, everyone who sees the establishment as providing a public service which should be known, observed and followed.

Understanding the functions of the university (analytical organigram) therefore presupposes a different design according to another vision, by which the university makes known how it uses its resources.

The coherence of this operation is due to the fact that the framework, design and name of the activities are known, recognized and, to this end, validated by the board of directors in the light of the strategic axes that it has helped to define and approved.

The forward-looking management of jobs and skills (GPEC, under the responsibility of the Human Resources Department) is a sector of concern in its own right, whose interrelationships with cost accounting issues are important, because although GPEC makes it possible to project the evolution of jobs and positions, it also concerns training and mobility support needs and requires a global policy.

We understand that everything fits together: the support functions (financial, human resources, accounting, assets, logistics, information systems) make it possible to implement the university’s major missions (teaching, research, student life, international, development, partnerships, governance) and their support functions (documentation, orientation, continuing education, university press, etc.).

It is understood that this strategy requires the alliance of politics and administration, giving each other meaning and power to act, a transversal vision and operationality.

2.1.3.1. Modernizing and managing

In accordance with the French Law on the Freedoms and Responsibilities of Universities, the preparation of universities for the exercise of the responsibilities and competences devolved by the State involves modernizing the support functions (finance, human resources, information systems) in order to be able to take full responsibility for the management of its budget, a large part of which relates to the payroll. The conclusion of the reports of the Inspection générale de l’administration de l’Éducation nationale et de la recherche (IGAENR) that accompanied the institutions in their transformations (between 2007 and 2011) emphasized that the challenge for the coming years, once the transition to RCE8 had been completed, would concern the dissemination and appropriation of a culture of steering at the level of training and research activities and their support functions.

During a term as vice-chair of the Board of Directors9, the author integrated a collective dynamic (one directorate and one executive) focused on the modernization of the RCE. The aim was also to ensure the transition and continuity of the public service and to integrate the new challenges – in particular the construction of the PRES then the COMUE10 bringing together two universities and various institutional partnerships, around scientific and organizational projects (pooling of tools and organizational methods, consolidation of the steering culture).

The strategic line of the new university grouping aimed at its modernization while wishing to develop its core business (research, training, internationalization, outreach) and its territorial registration. Particular attention was paid to the issues of innovation, professionalization of studies and autonomy of actors. The national and institutional context strongly encouraged this. The political and social concern for training, preparation and support for working life is a constant that has become even more evident in recent years, together with an ethical and civic questioning of the relationship between the State and civil society, clearly expressed in the requests of the supervisory authority for the improvement of training activities. The reform of accreditation11 goes in this direction: it is a matter of affirming the principle of subsidiarity by entrusting institutions with the responsibility for quality and sustainability – financial, human, real estate, logistical, etc. – in order to ensure that they are able to meet the needs of their clients – their strategy and training offerings. The conclusion of the IGAENR12 audit, preparatory to the devolution by the State of increased competences and responsibilities to the university, stipulated that the challenge of the coming years would concern the diffusion of steering at the level of the intermediate components (35 research teams, 4 doctoral schools, 17 training units: heterogeneous entities accommodating between 300 and 4,000 students, between 30 and 200 staff, and offering a total of about 100 degrees).

It should also be stressed that the new regulations give a central place to the university boards of governors, which are the bodies that deliberate on institutional strategy in the light of the constraints and projects that are now more directly assumed. Composed of about 30 members, half of whom are professors, the board of directors approves the establishment contract. Political commitment is crucial to guarantee a dynamic of change both through the slow mutation of symbolic frameworks (representations, values) and through the construction of working methods and tools for all the institution’s support functions and functions.

Conducting such a project implies acting in the short, medium and long term to:

- – organize action at various levels;

- – be able to adjust projects continuously and according to the hazards that arise along the way;

- – use tools and build on them if needed;

- – identify material from which to act and resources to be associated with the overall movement.

The support of teaching colleagues and external partners was sought on certain strategic points: days of reflection were organized according to the expectations of the territory with regard to the university, the enhancement and recognition of student commitment and forms of innovation in training practices.

Other subjects have been the subject of teacher-led studies and reports, such as the mapping of training and research fields in the light of territorial partnerships and foreshadowing the structuring of training and/or research fields, in line with the State-led accreditation reform.

The university in which we practiced, with a strong experimental tradition in the human and social sciences and the arts, focuses on issues of the contemporary world. It is committed to and recognized in the construction of new areas of knowledge, particularly the digital humanities.

It is on this potential, objectified and analyzed, that the modernization movement should be based. In terms of governance, the aim was not only to share the project within the political sphere and to drive the administrative side of the project, but also to establish and consolidate the achievements sufficiently to ensure continuity and duration. The entire project was also to be part of the general policy of the grouping of establishments (COMUE): by becoming part of it, the establishment was taking its part in the emergence and dynamics of the whole. Needs in terms of new skills and new missions (lifelong learning, digital, language training, schooling, qualityevaluation) have emerged, as well as the need to lead teams of collaborators, administrative managers and teacher-researchers.

The period of preparation for contractualization with the State is a key period, and begins with the institution’s self-evaluation – in particular on issues of success, professionalization, innovation, dissemination – and the formalization of strategic axes for the coming period. We have set up and supported a series of workshops bringing together some 40 volunteer faculty members and a few administrative or technical staff on selected themes (networks and territories, democratization and student success, digital deployment, jobs and working conditions). At the same time, the shuttles with the guardianship and AERES13 directed the institution’s vigilance on the points of fragility (success, social integration), inviting them to conceive a clear strategic line, structuring all the activities perceived as too heterogeneous and dispersed.

Strengthened by our research and monitoring activities on the issues of mobilization of actors in education, we observe that the stagnation of reflection on the recurrent failure of students and the overall inefficiency of aid mechanisms encourages us to address the issue more strategically14: act at the meta-transversal level of the institution, in project dynamics, so that the strength of scientific activity (production of knowledge), a force for innovation, leads not only to academic and scientific recognition, but also to increased professionalism among all the protagonists (teachers, partners, students); put at their service the expertise of the research teams in social innovation and the institution’s capacity to cooperate with a young and resilient socio-economical territory, and with actors in the professional world who are sensitive to innovations.

While these synergies are already at work within the institution’s transformative programs, new efforts are focusing on training activity in its broadest sense, to upgrade and restructure the sector and to spread the culture of subsidiarity in the spirit of the accreditation reform. At the managerial level and through an HR perspective, it is also a matter of reconnecting and rebalancing two functions that are too often distant (research and training), encouraging a more fluid circulation between the two spheres and a more direct anchoring in social reality through an understanding of the changes and challenges of today’s world. This evolution has led to a diversity of actions:

- – reorganization of services (schooling, steering), monitoring of training provision, development of a culture of lifelong learning (FTLV) and bringing the initial and continuing training sectors closer together; formalization (organization charts, mission statements) and simplification of procedures and making schooling channels more fluid; choice of gradual restructuring through support work in consultation with the technical committee;

- – budgetary and pedagogical dialogues: analysis of practices with regard to the objectives of the contract and the institution’s strategic projects; monitoring of territorial cooperation and the emergence of business sectors; economies of scale and room for maneuver: transformation of employment support (experimentation of assignments for two years);

- – demonstration of the appropriateness of choices and reconfigurations before elected councils (board of directors, academic council, technical committee, board of faculty directors); construction and dissemination of tools (shared sustainability and self-assessment indicators);

- – installation of intermediate management layers: proposal to create a position of program manager and design of a support plan for the new teaching responsibilities, overhaul of the policy around teaching work, implementation of transversal management platforms, pooling of budgetary, HR and engineering resources.

2.1.3.2. Outcome and introduction

This modernization drive was partially successful because there was a lot of resistance. The failures or simple difficulties kept the team on alert, to enable them to understand and move forward. The idea is to preserve a dynamic, to seek to share it, to maintain it in the long term, while thinking about the subsequent challenges facing the institution and the academic world. The challenge is also to find ways of ensuring continuity despite changes in teams, staff mobility and the renewal of elected board members’ terms of office.

Supervision and support for socio-institutional change require other forms of rationality (particularly in relation to time and space) than that which is usually useful to teacher-researchers: a rationality conducive to action and decision-making in the short and long terms, integrating, in order to master them, the constraints and risks inherent in any choice, an ability to work according to a project-based approach and in cooperation with colleagues or partners with diverse know-how. It allows the action and the management function to be anchored in a solid ground and offers as many opportunities to develop the practice of the profession.

It raises awareness of the mediation work needed on the part of those who accompany, coach and stimulate: mediation skills such as the ability to anchor oneself in tangible realities are essential. They are generally not improvised, but are worked out and acquired through a reflective effort focusing on the issues at stake in the situation and relationship, the stakeholders, the communication contract, ethics and the mediator’s room for maneuver.

Knowledge about psychological development within an educational or training relationship can support reflection. In the field of educational or formative accompaniment, mediation is defined as the capacity to produce a symbolization for oneself, for others and for collectives. It is also a power over the other (the psychoanalyst Piera Aulagnier evoked in 1975 the “violence of interpretation”).

It is as much a risk as it is an opportunity for alteration and transformation. Its vitality presupposes its renewal and elasticity: the capacity to “remake” itself, to cultivate a form of resilience, to imagine and bring about other forms and other representations, other types of mediation and sharing of meanings (Bouissou 2017b). It is therefore an active role assumed by a mediator, who is an interpreter who handles language and representations in a potentially creative way, capable of marking the spirit of the other and accompanying him or her in a universe, or even in a “multiverse” of meaning (Kristeva 2013):

“The absence of living mediation has the effect of considerably impoverishing the representation of reality, because it ends up denying it the richness of being able to be perceived in a thousand ways. The real separated from the possible is a stone: what is a real without the burning core of its inexhaustible possibility of being? Living mediation is the work of those who know that reality is not entirely given over to the logic of power and domination. To know it, one must be it, that is to say, one must be oneself of this world which is not entirely given over to the logic of power. Living mediation brings together in the same gaze what is and what can be, and brings one into another order of relationships.” (Muraro 2004, p. 137)

2.1.3.3. Development and mediation

This question of mediation and protection, allowing the subject (child or adult) to “grow up” by progressively integrating the tools necessary for his or her life in the world, is therefore essential. The goal is to ensure that the subject (or group) is comfortable enough, but not so comfortable that they are not frustrated by the reality of the situation, as Donald Woods Winnicott says about the “good enough” parent. In the relationship of care with the child or in the social relationship between adults, mediation has the same capacity to contain, symbolize, protect and guide. Bion (1962) sees it as a mechanism by which the adult “lends their psyche” and takes charge of the transformation of the anguishing perceptive elements into constructed, formalized, distanced, less anxiety-provoking and ultimately integrable and nourishing psychic contents for the child. Anzieu (1974) evokes the “skin-self”, a psychological membrane built in the relation which is then gradually integrated by the subject, protecting the psyche, filtering the external or internal aggressions, while at the same time guaranteeing a good grip on external reality and a fluid relation to intimacy. Balint (1961), who is interested in the group psyche, helps professionals develop emotional intelligence and protect themselves (individually and collectively) from defensive projections and anxiety.

In the managerial and organizational field, mediation is the art of contributing to collective life and conflict resolution by seeking the best outcomes for all stakeholders. The challenge is to go beyond wars or the clash of positions, to focus on content (a common good, not a monopoly) and on processes (what circulates and connects), to move from frontal and binary opposition to the search for a third element that shifts the stakes and reconciles positions. According to Follett (1924), the integration of conflict allows for a socio-cognitive and relational well-being that benefits all parties, as opposed to compromise and power relations, and characterizes constructive leadership.

Participating in the undertaking of mediation therefore means bringing together the conditions for a creative work of elaboration that is both distanced and anchored, which guarantees sufficient space for the life of the spirit and makes room for the encounter with otherness; this arrangement must also be contained by an explicit rationality, preserving it from arbitrariness and violence. From this point of view, mediation concerns at the same time the educational relationship, the reading of traditions (inheritance and transmission), the interpretation of human and psychic facts and the life of groups. In this way, we wish to consider from the same angle situations which, although always singular, call for a reflection on symbolic, social and psychic dynamics and the way in which they intertwine.

These reflections show the interest of understanding the psychic functioning and its genesis in the relationship (from the parent–child relationship to the adult–adult, individual–group relationship), in order to grasp in an open, flexible, inventive way, the question of accompanying adults in training and change. The aim is to help relational (inter-psychic) practices to bring about psychological vitality and to instill orientation, acquisition and modification at an individual (intrapsychic) level.

2.2. Supervision and care

Returning to the fundamental knowledge and humanistic principles concerning childhood (as the childhood of the human being) can be an opportunity to deepen and rediscover resources at work in every developing being. Pampering and continuing to educate the child that each adult carries within themself, returning to it at different stages of life, making it grow and maintain an attentive relationship with it guarantees the coherence of experiences and the meaning of their branches, through the vitality, energy and imagination attached to the figures of childhood and its motives. The process leads to a genealogical trace back to the sources. It also gives any thought enterprise an untimely and modern impetus, in the sense that Macherey (2005) gives to these terms: the capacity to problematize in a renewed way the elements of the present reality.

We will distinguish the child from the infans (i.e. a child who cannot yet speak). The period of childhood is that of the first meanings, that of the first education, where the world perceived and spoken is “the” world. It seems that in case of subsequent trauma, tearing, mourning, de-symbolization or just an ordinary transition into adulthood, contact with that child (primordial, vulnerable and powerful) regenerates, revives and moves forward.

2.2.1. Childhood as a narrative

Returning to childhood is a meta-method for action, both in a creative relationship and in a search for anchoring and renewal (Bouissou 2015). During a seminar in Port-au-Prince, as part of a master’s degree in philosophy and literature, the author reflected on the question of childhood. The problem resonated particularly with the anniversary of the earthquake that had destroyed a large part of the country and the intense activity of rebuilding walls and rebuilding institutions in which the university was involved. The reflection took place in four stages: What is growing up? What is remembering? What is leaving, coming back and deferring? What is talking? These questions marked out an open research on philosophy and literature. The idea was to carry out in 18 hours, spread over six days, an approach to questions of time, childhood and narrative, drawing on political philosophy through Arendt (1972), Agamben (1978) and Fleury (2005), literature through Sarraute (1983) and Pachet (2004), aesthetics through Benjamin (2000), theater through Novarina (1999) or Elkabeth (2011), and psychoanalysis through Kristeva (1996).

The idea was to diversify inputs, points of view and contexts, to show that a certain use of childhood propels and opens up the future, provided that it is developed and understood not as a fixed, unique and closed-in time, but as the result of an actualization and access to speech, lasting, changing, evolving, bringing childhood before us. The aim was to show how the work of thought and creation (including at the most intimate level of the inner life described by Pachet or Sarraute) rejuvenates and singularizes problems, while at the same time reflecting on the notion of untimely modernity, based on Macherey (2005). The bet was to work on the world’s intellection as much by the rigor of the method as by the aesthetic inspiration.

The students in Port-au-Prince were destined to become teachers and were beginning to work as teachers, alternating with their training. As enthusiasts of French and European culture, concerned about their national history and embedded in turbulent daily realities, they had to be able to acquire the advantage, it was the postulate of an intellectual but nevertheless practical game, rooted in life stories and concrete cases. Interdisciplinarity was welcomed in this master’s program. More generally, the aim was to arouse and transmit a taste for research, a sense of experimental approach controlled by rigor, understood as a personal call to be surprised, while at the same time being anchored in the fundamentals of humanism and the Aufklärung; this must be able to be deployed wherever thought is exercised: the university as a third space and training as a background. This journey in four stages (change, memory, exile and speech) allows us to think about the way in which change can occur, in continuity (notions of difference, untimeliness, performance, metamorphosis), and allows us to develop, at the heart of educational issues, an interest in artistic forms. It is about the search for a passage, a divestment, beyond the balance of power, a passagium:

“The Latin expression actually refers to leaving home and moving beyond, without suggesting the idea of violating a limit. In the Middle Ages, everything that concerned travel (time, space, movement) was called passagium and took the traveller out of the usual places to go somewhere else, an unknown elsewhere, to which the traveller’s mind was turned.” (Muraro 2004, p. 136)

“There is no passagium without a body that lives it and recognizes it from within when it takes place, because here there is no boundary, in the conventional sense, to identify it. The geography of this surpassing, never reversible, is internal as much as external; the two are intertwined.” (p. 137)

2.2.2. Storytelling, reconstruction, the humanities of education

The humanities (philosophy, literature, the arts) offer similar inputs and guidance to the fields of science or educational technology. They deepen our knowledge of the subjectivities at work in transformation, creation, renewal and innovation, without abandoning an attraction to the dark, unexplained and difficult to grasp aspect.

Drawing on Haitian trauma and expanding on the metaphor, the author has delved into issues of development, temporalities, failure, grief and reconstruction (at an individual and collective level). We also dealt with questions of exile, identity, trajectory, corporality to be cared for and cultivated for an identity in the making.

Developmental psycho-sociology and the humanities of education and philosophy have proven to be powerful intellectual and ethical drivers. The preparation and conduct of this seminar was synchronous with our commitment to the university’s management, nourished reflection on the institution and its transformations, and made it possible to rethink the stakes by placing them in a different relationship to time and space. The questions raised by the seminar were as relevant at an individual level, for any student or professional who may wonder about the surrounding world and its place in it, as at an organizational level, for a university with its culture, its past, its pathway and its potential.

The master’s seminar was part of a global mission of the university to reconstruct the University of Haiti and implement a project to build a Caribbean doctoral school. Beyond the social and institutional dimensions that it may seem decisive to address at the university in the context of student training or research in the human and social sciences, it is important to consider the personal, normative dimension of each individual in his or her relationship to work and study. From this point of view, there is no important difference between students and professionals, all of whom should be able to find meaning, frameworks and minimum security in a space that is “good enough” – to paraphrase Winnicott (2008) again – that is, sufficiently involving and conducive to taking risks and responsibilities, to the individuation of a professional ethos and to the care to be taken with adult issues.

As already mentioned, the mediation function is essential in the transmission professions. It is important to delve into the question of the primordial and access (vs. hindrance) to symbolization, in their relationship to human language and communication.

The more we advance in the experience of supervision, the more necessary it becomes to understand how a human relationship can be established despite the accidents of this symbolization, how a human action can be realized despite the many obstacles to this realization. In this sense, Deligny’s work (2007) is a fascinating resource, showing that what we find in an autistic child – and deep down, within oneself – is precisely the primordial, that is to say, this anterior, primary state of being, which concerns all beings, the common ground that we all share, before the social, linguistic and normalized facilities come into play, blocking the natural access to the primordial. This work is all the more valuable in that Macherey has recently taken it up in the context of his general reflection on norms, ideology and subjectivation.

The challenge of reflection is not to attest to differences between individuals, but rather to differences within oneself, between two states, two relationships to oneself, which can be played out, worked on, actualized. Thus, the a-conscious subject and the self-conscious subject represent the two edges of each person’s existence and relationship to oneself (Macherey 2014).

This idea of human indeterminacy is reminiscent of Simondon’s notion of the pre-individual or phase-shifting, indicating the possibility of return, reserve, revitalization. It also evokes the Canguilhemian spirit, which seeks to break down norms when they distort common sense and make people sick. The return to the birthplace must be understood as a passage, revision or stay, of course momentary. It also makes it possible to remove certain prohibitions or constraints imposed on thought: ideology, doxa, normalization, atomizations, compartmentalization and divides, and to seek to find something more fundamentally anthropological and cultural, to seek to draw on it or even to anchor oneself in it:

“As the sessions progressed, they expressed better what made them want to come back. It was the word, a certain way of speaking which they had never practised before and which did them good… We understood that we spoke to each other only with the tacitly accepted presupposition that we were going to believe each other… As soon as they were ready to speak together, the pact of the word was made between them, and the promise silently inscribed in every word was renewed. At first they trusted each other, they were willing to believe each other from the start.” (Leclerc 2003, pp. 117–118)

“The interview can be considered as a form of spiritual exercise, aiming at obtaining, through self-forgetfulness, a true conversion of the way we look at others in the ordinary circumstances of life. The welcoming disposition, which inclines to make the problems of the respondent one’s own, the ability to take him and understand him as he is, in his singular necessity, is a kind of intellectual love: a gaze that consents to necessity, in the manner of the intellectual love of God, that is to say, of the natural order, which Spinoza held to be the supreme form of knowledge.” (Bourdieu 1993, pp. 913–914)

The evocation of the primordial also makes it possible to rediscover the questioning of the effort of reflective writing as a mode of professionalization and development. It is the effort to go back to the first motives for an action or the beginnings of a project, and to proceed to the anamnesis and formalization of the actual achievements (their failures, their successes). This effort is more or less successful: it is not easy to get around the resistance that formalism puts up against analysis, to find a mode of creativity and a search for truth that requires genuine involvement.

We relied on Buber (1959), Arendt (1983) and Foucault (2009b), who have led reflections on ethical conduct and self-government. Clarification is needed when we want to listen to the spoken word – in support, training, research, or more broadly as individuals exposed to a very large quantity and variety of words, speeches and languages – about the criteria of truthfulness to which we give credence, which is fundamental to the professions and practices of human relations. The same question arises with regard to political thought in a democracy: the relationship and argument of force versus the force of argument, interlocution and confrontation with otherness (which we will return to in section 3.2).

The importance given to the primordial also lies in the attachment to an integrated vision of conflict as Follett (1924) maintains in relation to supervision and management, or as Meddeb (2006, 2011) has constantly stated about the Mediterranean and Middle Eastern destiny: both of them (although living through very different space–times and issues) are driven by the search for a way out integrating the alternative point of view to gain intelligence, civility and civilization.

2.2.3. What use is care?

From the concern for the primordial, such as the Deligny door, comes quite naturally a rapprochement with the notion of care. This is a very recent development in view of the intellectual movement in which Deligny found himself in the second half of the 20th Century – the time of the socio-institutional analyses that guided care and education practices in Europe and left a lasting impression on people’s minds. However, we see a possible and relevant extension of this critical socio-institutional approach to the notion of care, which places the question of work, collective frameworks and vulnerability at the heart of the analysis.

This idea is studied more deeply by students in education or teaching training (Bouchareu 2012; Schirmer 2014): through the analysis of professional practices (pedagogical advice, animation, supervision or teaching), they conduct a psycho-social questioning of their work universe and thus gain a broader understanding of the educational relationship itself. Supervision, adult support, professional mobility, individual development, creativity and evaluation become theoretical and practical issues that can be articulated through the notion of care as attention to human vulnerability.

These are preliminary studies prior to enrollment in doctoral research and initiation to professional or scientific writing; they also lead in some cases to a professional change (evolution towards training and support for educational staff in difficulty, for example). Sometimes the collaborative work between former student and teacher continues beyond graduation, in a more informal way, and gives rise to perspectives on the respective experiences; this is a good example of “lifelong learning”.

Rather than annexing the question of care to the sole division of labor between the sexes – and confining the notion to the private sphere – we propose to use it to question work, or any human activity in its subjective and vulnerable, that is, stressful and formative, dimension, which is constitutive of the professional ethos. Vulnerability is to be considered as a quality and a primary condition of human action, obliging the subject to signify and symbolize his or her life and to find/enable him or herself to do so. The concern for the primordial is to question oneself about one’s first motives, the family messages heard in childhood that forge self-representations orienting one’s trajectory; becoming aware of them is a means of maintaining a relationship with these first markings and allows one to not adhere to them in their entirety. In other words, to not be entirely governed by them.

Care directs our attention to the ordinary, to what we are not always able to see, but which is before our eyes (Laugier 2009) or within earshot (as the writer Sarraute shows, through the notion of tropisms, see section 3.4.2.2). It induces a marked sensitivity for details, a choice of perception for the individual, and restores dignity to what is usually neglected, rehabilitating tasks that are discredited and disqualified:

“The care ethic is emerging as a concrete, contingent and contextual ethic. It privileges attention to the uniqueness of others, to the specificity of situations, to the relationships in which the subject is inserted on a case-by-case basis; relationships that cannot be ignored in view of their importance for his or her fulfilment and for his or her very life project. At the same time, it emphasizes the universality of the need for care. This is the source of moral choices and social cohabitation between responsible subjects.” (Pulcini 2012, p. 61)

Basic human needs, and how an environment or organization addresses them, are also at the heart of new, environmentally sustainable approaches to human development. In this perspective, as deployed by Nussbaum (2012), it becomes possible to assess the level of development of a society with regard to a dozen criteria, complementing and being assessed against the level of national economic wealth: life, health of the body, its integrity, senses – imagination – thought, emotions, practical reason, affiliation, attention to living things (animals, plants and nature), play and control over one’s environment. The reference to this work can be used to think in an integrated way about the support of people, especially adults, for whom it is necessary to think about development in a plural (not univocal) way and to take into consideration the variety of areas of existence, experience and training that adults can invest and articulate.

In the context of training and research, the ethics of care leads to the development of an open conception of work (research, training, innovation and experimentation), with already experienced professionals, with contrasting backgrounds, even if they are novices in research (Bouissou 2017b). The work of the feminine makes it possible to re-examine the primordial needs (one’s own, those of others) and to do so one must find solid support. This is why the approach of Nussbaum (2008, 2012) – itself based on the work of the economist Sen (2003) – seems very relevant. Her work concerns a whole area of ecology: it is not just a simple interest in women – a minority, reduced to the extreme by all situations of violence, poverty and abandonment – but it is necessary to think again about the ecosystems in which they live, which they help to modify through their initiatives, giving thought to the interdependent exchanges and movements between goods, elements, natural or civilizational phenomena.

The deconstructive analysis of male domination has thus been enriched in recent years by an eco-feminist perspective that seeks to consider and articulate different vulnerabilities (social, ecological, economic, psychological) to socio-political concerns and the search for new models of development. Transversal to disciplines, sectors of social life and the variety of human frailties, it carries an ideal of empowering vulnerable individuals, seeking to objectify and strengthen the support available to them to enable them to cope with living conditions that hamper them. At the theoretical level, this paradigm allows for the intersection of socio-eco-cultural, subjective and gendered issues where the feminine becomes a global issue and where questions of ecology, primordial needs, developmental tasks, material-immaterial wealth, immersion in the environment and the organization of social life can be addressed together and enriched.

2.2.4. A material-immaterial treatment of the public thing

The following words illustrate a concrete operationalization of the concerns of care, in the field of work at the university, more particularly around the conception of a reference frame of tasks and missions of teachers and teacher-researchers15. The challenge is to know and promote the different areas of intervention and activity of teachers (research, training, orientation, supervision, evaluation, orientation, prospective, management, dissemination, administration, etc.) and related tasks.

The approach requires structural agility (in terms of organization and metacognitive actors) to reconcile core business and resource management, but also an ability to think in terms of the primary, primordial meaning of a public action and the means that have been or will be allocated to it. The relationship with time takes on a different character when a prospective reflection is undertaken on the evolution of resources with regard to a development strategy. The relationship to work can also be transformed, deepened and renewed through the analysis of activities which, outside of banality and routines, reconsiders and re-evaluates their primary meaning, their raison d’être and their scope. Striving to understand budgetary policy issues, which are intrinsically linked to human resources, enables any organization to take a step back and regain a sense of work and common purpose.

We initiated and shared a reflection between a panel of teachers, the human resources department, management control and the steering committee. The first step was to draw on texts defining the status of teacher-researchers, and then to make an inventory of the different categories of teachers and all the possible roles. From a political and strategic point of view, one cannot avoid a study which problematizes the question: what is at stake and what problem do we want to answer? The main answer to this question is the non-recognition of many tasks. What are the supports and constraints that we need to know to move forward? A SWOT16 analysis can stabilize the diagnosis of the benefits and risks associated with the definition of a reference framework for teaching and research activities, which it is anticipated will be resisted.

Very quickly, we gave up focusing on the translation of assignments in terms of hourly equivalents, due to the very great diversity of practices within the institution itself, and the unpreparedness of the actors to accept a more standardized operation. It was necessary to move forward in small steps, finding constructive support and concrete tools. The establishment contract is one of them, because it provides a framework (temporal, methodological and legitimated by institutional dialogue). The project-approach included stages and deliverables (to be presented to the statutory boards and discussed) and aimed to enhance the value of the work carried out with the community and the guardianship (as part of the contractualization of the establishment).

The approach was also in line with internal and external developments: development of analytical accounting, the need to know training costs, reorganization of certain support functions within the school, implementation of the accreditation reform, redefinition of a compensation policy for teachers, etc.

All levels of the university are concerned with the question of the visibility and enhancement of teaching work: from a technical point of view, tools and skills are needed to build, make viable in the medium term and implement the approach; from a political point of view, it is a question of challenging elected officials on the issue and eliciting their support; from a professional point of view, it is all teachers and employed teacher-researchers who are involved and must understand the approach. The places of operation of this draft reference system are: the internal management of teaching teams, the HR career management services, the elected bodies (board of directors, academic council, technical committee, board of directors), the steering sector and the information system.

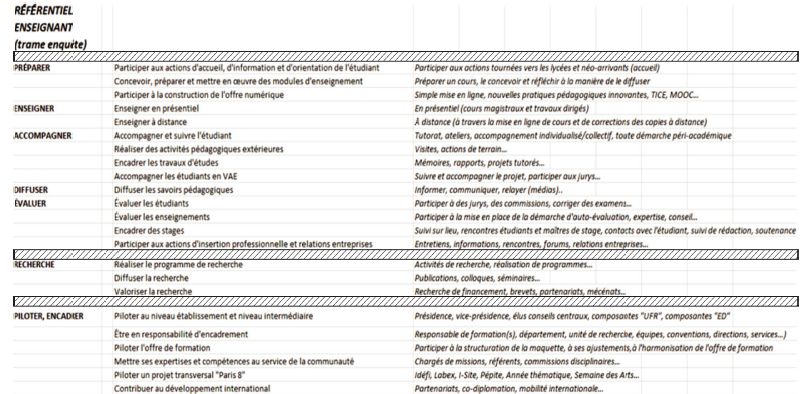

A survey of teachers made it possible to draw up a map of actual activities, to identify their plurality as well as their coherence, to formalize them as adequately as possible, and to provide stabilized points of reference for teachers and team and project managers (see Table 2.1). It is a question of approaching teaching and research work in the most exhaustive way, as a mission of public action. We therefore considered the public service obligations in terms of working time statutorily defined in a contract of 1,607 hours per year for a teacher-researcher, 803 hours for research and 803 hours for training (including 192 hours of teaching equivalent tutorials for teacher-researchers and 384 hours of teaching equivalent tutorials for associate professors, and the remaining time corresponding to the various tasks of preparation, monitoring, organization and evaluation).

On the basis of the work carried out to set up analytical accounting, we have tried to describe as exhaustively as possible the teaching activity in all its forms (and which may concern any status) as well as research activity (less in-depth, because of the difficulties in stabilizing sufficiently generic categories of activity) and have constructed a numerical application to the destination of each teacher and teacher-researcher, making it possible to assess the time devoted to each of these activities. This stage is a first step in the definition of a reference system for teaching and research work, which requires a longer period of time to be approved by the entire community, continuous political support and consistency between the reference system and the compensation policy.

Table 2.1. Teaching and research activities framework detailing elements involving preparation, teaching, support, dissemination, evaluation, research, management and supervision

Each act of work must therefore be translated into the terms of the reference system (in one of the four areas), which means that all positions and functions must first be “rated”. It is a question of working time (financial mass equivalent) and not of persons or categories. It is the nature of the assignment that determines the allocation of its wage costs to the activity (costing structure), not the positioning of positions within the establishment (reporting structure) or its categorical status (hierarchical structure). The question of depersonalization is all the more crucial since the budget of a university – and all the more so in the human and social sciences – concerns to a very large extent its payroll, for an activity oriented towards symbolic goods and an immaterial economy.

The problem of full costs leads to a change in the way an entity (small, like a training team, or larger, like a university) is organized and operates, and raises awareness of the culture of university management autonomy and subsidiarity. When this culture is sufficiently shared by the actors, an institution’s management can establish “objective-means contracts” with its various components (as is commonly done between a university management and an university institute of technology), which gives them greater management autonomy and room for maneuver in research and the management of their own resources, while associating them with the achievement of the institution’s objectives; the contract commits both sides to ensuring that the material and human resources ensure the sustainability of the ambitions. It is a negotiation from which each party must be able to gain benefits, recognition and room for maneuver.

2.2.5. Care of the feminine: gardening and foresight

“Train with a few others, small groups of friends in which serious and fraternal conversations can take place. Those who carry heavy responsibilities need to break away from their loneliness and talk to peers about what is beyond their job. For them, it is about something completely different from associating their interests or looking for a pleasant relaxation: no club, no party, no association, just a real meeting.” (Berger 1964, p. 268)

In collaboration with female colleagues, we have focused on the issue of “women’s work”, in which the libido creandi plays an essential role (Fouque 1995; Bouissou 2017b). What is characteristic of this collective is that women continue to learn and educate themselves. For to begin is still to learn, with confidence and humility, to develop an ethos to welcome the new – “I know deeply that I will use what I learn”. It is a question of placing oneself in a problematic environment, creating it, inventing it, desiring it. The attitude is a duty to be inclusive, a “we”, capable of creating the right professional context that respects and promotes the vital needs of its actors: a “we” more interested in circumstances and processes (method, strategy, resources) than in idiosyncratic positions; a primordial, choral “we” that gathers and overcomes infertile divisions (reconnecting the idea and the reality, the near and the far, the self and the other, the endogenous and the exogenous); a “we” of diverse professions, experiences and competences; a “we” of culture, a “we cultivate”.

It is a question of moving from the self of experience to the political and strategic us. In order to do this, an openness to philosophy and the humanities is essential:

“The question of education and training was not only to transform, to integrate technological innovations, to give birth to new teaching methods, to conquer scientific legitimacy, but also to question the meaning and orientations of education, to study its discourse, to observe, to examine its practices, to question its logic, the links, the future, the will of powers, the stakes, the wanderings, the discoveries.” (Cornu 2016, p. 20)

Women’s work also means the possibility of proceeding in terms of hypotheses, succession and performance. It questions the possible meanings of the genitive (feminine) in its objective-subjective (active-passive) form. How can this work be supported, both in terms of the content to be transmitted, the types of relationships to be established, the organizational tools and the economy of environments? In order to avoid the risk of a rupture or fracture between seemingly difficult to reconcile or traditionally separate issues, our concerns will be addressed in terms of “transindividualization” (in Simondon’s sense, see section 3.1), in the spirit of a philosophy of matter and fluidity, directing our attention to the potentials residing in all forms of life (psycho-social, technical, physical) and to the flows of energies that cross them: the progress of individuation of a body, an object, a subject, making possible (and made possible by) the progress of its associated environments. The work of the feminine thus consists of jointly tackling the problems posed by everyday reality, its own individuation and its epistemological consequences: I am accomplished by the intellection that I accomplish.

The feminine – beyond or beneath sex or gender – is a style, a gesture, a paradigm, a modus operandi, capable of going beyond binarities or essentialist or categorical visions in favor of the search for an acting principle:

“It suggests that living in relation to an environment, for man as for all living things, does not consist of submitting to rules fixed once and for all by the nature of the surrounding environment; but it is to sketch out, by taking risks, and with incompleteness in mind, an inventive approach that configures its goals within the movement by which, without guarantees, it moves towards them according to a certain style of existence.” (Macherey 2016)

It is an attitude, a relationship to the world and to oneself, unstable, in movement, which one can, and even must, seek to develop, a potential that exists in each person:

“Every individual is applied to this stylistic task. It transforms everyone’s relationship to their condition. But it also circulates outside a diversity of gestures which, insofar as they are individualized, stabilize appropriable forms. By exposing oneself, by offering oneself to perception, any way of giving an aspect to one’s presence, of occupying positions, of shaping one’s most manifest movements, as well as one’s most intimate ones, of following models or of instituting them, one is, well and truly, making a shareable resource of a possible human being.” (Bidet and Macé 2011, pp. 408–409)

These are research techniques that consist of altering stereotypical representations – in everyday life (e.g. identity tensions, role adhesions) and in scientific life in terms of descriptive concepts that perform or essentialize – and of attempting an articulation between idiosyncratic, interpersonal and conceptual dimensions.

The issue at stake is to try to dissolve the distinction between mental action and social action. It is a scientific, educational, strategic or axiological preoccupation: affirmation of values, of a must be, integrating questions of governance, supervision and management.

It is a matter of developing qualities, including the so-called “feminine” ones. To develop them, in the sense of refining, is to go through conflict and to individuate a style.

It is a resurgence of the imaginary in thought, for example through poetic writing, as a mode of alteration, revitalization or combativeness (see section 3.1).

It is an invitation to give care – individual and collective – an essential and driving role in health and development; the feminine helps us to look for the tools to embrace these issues, not to be satisfied with divisions and binarities, watertight categories, but to deal with contradictions and annoyances:

“Being a feminist means staying as close as possible to realities – and therefore analysing them as they emerge, and not from a pre-established ideological or political schema. We must listen and be attentive to suffering for what it is, and not only from our personal and situated way of living and defining it. It is essential to start by situating yourself. Situating one’s word, situating where one is speaking from, rather than universalizing one’s statements, is a first step. Everybody is situated socially, economically, politically, etc., in the world. And constructs a discourse from a position – and for certain reasons.” (Ali 2016)