8

Managing the Cable Television System

This chapter considers cable TV management by examining

• franchising and refranchising procedures

• managerial functions and responsibilities, with special attention to programming, economics, marketing and promotion

• revenue enhancement, and the role of digital products and services

• the regulatory environment in which cable systems operate

While Guglielmo Marconi was working toward his dream of a telegraph system without wires, he would have laughed at the irony that, less than a century later, telecommunications with wires would again be all the rage. To Marconi and other electrical tinkerers of the early twentieth century, it was a great goal to one day be able to send messages over long distances without the need of wires. These electronic pioneers brought us radio and, later, television. All the while, the fact remained that many more messages could be sent—much more clearly—through cable than could be broadcast over the airwaves.

Marconi might have laughed. But broadcasters are not amused. Cable is a major competitor, siphoning off audiences, revenues, and programming from conventional terrestrial television services. Into the new century, the ultimate irony is that hard-wired cable is itself under attack from wireless-to-home satellite transmission.

More than 8,800 cable systems pass 97 percent of the nation’s 109 million television households. Cable penetration totals almost 67 percent of those homes, yielding more than 73 million subscribers. Of that number, 50 million also subscribe to pay-cable services.1

Cable viewing shares have surged since the mid-1980s. In the 2003–2004 television season (Septembe–May), more than 50 percent of all prime-time television viewers watched ad-supported cable networks. This was the first time that cable surpassed all seven terrestrial broadcast networks.2 Cable had won the total day shares viewing five years earlier.

Cable’s audience growth has been accompanied by vigorous subscriber services and advertising revenue growth. Annual revenue in 2004 was $57.6 billion.3 It included advertising, video, Internet, phone, pay-per-view (PPV), video-on-demand(VOD), and other services provided by the nation’s cable systems.

Systems generate significant ad revenue, both local and national. Local spot revenue is growing quickly and was expected to rise to $6 billion in 2005. National spot at the local level runs about 20 percent of the local spot. That would put it at about $1.2 billion in 2005. Percentage compounded annual growth of cable ad revenue is in the midteens.

National advertiser-supported cable networks also generate significant advertising revenue. It was projected at $14.5 billion for 2005.

As they look to the future, cable companies are contemplating ways of consolidating their profitability. As indicated above, many have already begun the process of transforming themselves from program purveyors to suppliers of a full range of communications services. Subscriber growth will be limited because cable passes almost all TV households and satellite TV has become a real subscriber competitor. So, cable television must increase its sales of current and new products to an existing base of subscribers.

THE FRANCHISING PROCESS

Anyone considering a career in cable television should be familiar with the basis of cable operation: franchising. The franchise agreement provides the cable system with authorization to utilize public rights-of-way in conducting business, and establishes the terms and conditions under which this can be done. The franchise is to cable what the license is to broadcast stations.

From the beginning, the process was an area of shared responsibility between local and federal governments. Local governments issued the franchise because of the uses cable systems made of city streets and other rights-of-way. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) set standards for the provisions franchise agreements should include.

This structure of dual responsibility was confusing and ripe for abuse. Revenue-starved cities placed many demands on potential cable operators as preconditions to franchise issuance. This was true, particularly, when an exclusive franchise was at stake. In their zeal to win, competing companies made promises that were neither practical nor affordable. Bribery of officials to obtain lucrative franchises was not unknown. No one was happy—neither the local governments nor the operators.

It was in this climate that Congress enacted the Cable Communications Policy Act of 1984. The act continued the requirement that operators obtain a franchise. Franchising authority remained with local governments, and they determined the franchise term.

However, limitations were imposed on what a government could demand before granting a franchise. Cities could require franchisees to offer broad categories of programming (e.g., for children), but were not permitted to specify carriage of particular networks or services to satisfy the requirement. They could also include in the franchise agreement a provision that channel space be allocated for public, educational, or governmental access, so-called “PEG” channels. Systems with 36 or more channels had to provide space for commercial leased access; in other words, channels available for lease by persons unrelated to the cable company.

The 1984 law provided that the franchise authority might grant one or more franchises within its jurisdiction. Companies that overpromised in their eagerness to obtain a franchise could receive relief upon adequate showing of an inability to comply. Cities were entitled to collect a franchise fee from cable operators. However, it could not exceed 5 percent of the cable system’s gross revenue for any 12-month period. The act also freed systems from franchise authority rate regulation.

The history of experience under the 1984 act was not one of success. Basic provisions of the law were challenged in court by the cable industry itself. One such provision was that which allowed franchise authorities to award exclusive franchises.4 Deregulated cable rates exploded. The twin pressures of litigation and consumer reaction forced Congress to reexamine cable regulation. It did so, and passed the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992. The major impact of the new law on franchise requirements was a prohibition on the granting of exclusive franchises. The law imposed many new obligations on franchisees and ended the “deregulation” of cable.

Four years later, Congress passed the Telecommunications Act of 1996. This was a major electronic media deregulatory law that also impacted cable television.

Basic requirements of the various laws are reviewed in the regulation section later in the chapter.

FRANCHISE RENEWAL

As noted earlier, cable franchises are issued by local governments, not the FCC. Unlike broadcast licenses, cable franchises have no universally fixed term. Each local authority sets the term of the franchise or franchises within its jurisdiction. Before 1984, there were no universal rules for the procedure or for criteria to be applied in franchise renewals. Cable operators wanted the security that the FCC license afforded broadcasters. Broadcast licensees had a “renewal expectancy.” In other words, if they had rendered “substantial past meritorious service to the public” during their license term, they expected that the license would be renewed. On the other hand, the absence of renewal standards in the cable industry had become an impediment to investment.

The Cable Communications Policy Act of 1984 addressed cable operator renewal concerns. The act set national renewal standards, but left the administration of those standards to local franchise authorities. It also established specific timetables and criteria for renewal. Cable operators may initiate the renewal procedure by submitting written notice to their franchise authority. Any operator seeking renewal is entitled to a public hearing at which its past performance can be evaluated and the future cable-related needs of the community considered. The hearing must be held within a 6-month period, beginning no later than 30 months before the expiration of the franchise. At the conclusion of this evaluation, an operator may submit a renewal proposal. The franchise authority has a fixed period within which to accept it, or indicate its preliminary determination that the franchise should not be renewed.5

Denial of a renewal proposal must be based on one or more of the four factors examined at such a proceeding, which considers whether

• the cable operator has substantially complied with the material terms of the existing franchise and with applicable law;

• the quality of the operator’s service, including signal quality, response to consumer complaints, and billing practices, but without regard to the mix or quality of cable services or other services provided over the system, has been reasonable in light of community needs;

• the operator has the financial, legal, and technical ability to provide the services, facilities, and equipment as set forth in the operator’s proposal; and

• the operator’s proposal is reasonable to meet the future cable-related community needs and interests, taking into account the cost of meeting such needs and interests.6

The relative security afforded a cable operator by the law should not lead to laxity about the renewal process, however. Even though most franchises are granted for 10 to 15 years, many operators recommend an early start on preparing the new proposal.

If the franchisee has performed well during the franchise term, the task of obtaining renewal may not be too difficult. Nonetheless, the need to plan is extremely important. It should include identifying and resolving potential problems, striving to respond to community needs and desires for programming, and determining whether or not the system should be upgraded or expanded. With an eye toward renewal, many systems operated by multiple system operators (MSOs) sample customer attitudes in their monthly program guide.

Sensitivity to subscribers’ needs is essential. An operator who is not prepared will run into difficulties during the refranchising procedures. It is important to let the public know what has been accomplished and what is planned.

Presentations before the local governmental authority must be professional. Information must be accurate and displayed in a form that can be read and understood easily. Keeping files on complaints, no matter how minute, as well as complimentary correspondence, also will be of value.

Once the franchise has been renewed, full attention returns to day-to-day operations.

ORGANIZATION

Like a broadcast station, a cable television system is organized according to the major functions that must be carried out to ensure successful operation. While differences exist in organizational structure, the functions are similar and are allocated to departments. As new products and services are added to the menu, such as digital subscriber line service (DSL), high-speed Internet, digital tiers, and telephone services, supervision of these functions is assigned to existing organizational units. In the instances cited above, responsibility for developing these add-on products and services most likely would be assigned to the marketing director, with the assistance of the technical operations director. The following departments are found in many systems:

Government Affairs and Community Relations

These activities are often performed by only one person, with the title of director. Government affairs revolves around contacts with federal, state, and local elected officials, especially those who make up the franchising authority. The planning and execution of public relations campaigns designed to create and maintain a favorable image in the franchise area are the focus of community relations.

Human Resources

A manager may be the only person charged with human resource responsibilities. They include recruiting and interviewing job applicants, orienting new employees, developing and implementing employee training and evaluation programs, and processing benefits.

Business Operations

A director supervises the work of personnel in this department, which has responsibility for recording revenues and expenditures, handling collections, and computer operations.

Advertising Sales

The sale of local availabilities in advertiser-supported networks is a major responsibility of this department, headed by a manager. Many systems also sell classified advertising and spots on local origination channels. Cable television systems used to outsource this function. However, spot sales have become such an important revenue stream that almost all systems execute this function in-house.

Technical Operations

A director is charged with responsibility for this department, which engages in a variety of tasks. They include maintenance and operation of the headend (i.e., the facility that receives, processes, and converts video signals for transmission on the cable) and trunk and feeder cables; maintenance of the standby power supply; testing and adjustment of signal strength; installation and repair of drop cables and hookups to cable boxes and videocassette recorders; planning and construction of extensions to the cable system in new subdivisions and apartment complexes; and the dispatch of technicians. As noted earlier, some responsibility for installation and maintaining new products and services may be assigned to the department as well. The director is assisted by supervisors with expertise in the different operational areas.

Marketing

A marketing director heads this department. Its major responsibilities are the sale of the system’s program services and products to subscribers, and the planning and execution of advertising and promotion campaigns in furtherance of those goals. The department engages in market analyses to assess customer preferences and potential, and determines the packaging of new and old services and their price structure. The department also conducts door-to-door, direct mail, and telemarketing sales campaigns. Services and products also are promoted on the system.

Customer Service

This department, headed by a director, deals with all customer service and repair calls, inquiries, and complaints. This is an important function. Inattention to customer service in cable’s “build-out” years gave cable an image problem and stimulated national regulatory initiatives. Failure to service the customer promptly and efficiently can lead to churn, or customer turnover. As the rapid growth of satellite TV has demonstrated, customers do have a place to go and an inclination to do so if they are dissatisfied.

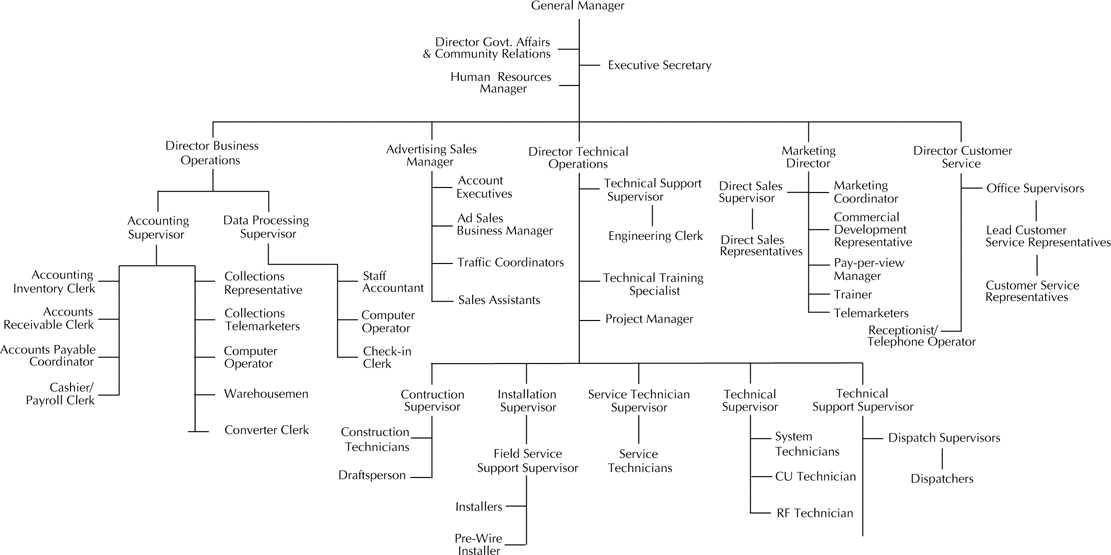

The number and organization of employees is influenced by the size of the system and by its status as a single entity or part of a multiple system operation. Management preferences also play a role, and scores of variations exist. Figure 8.1 shows how a system may be organized. It is headed by a general manager (GM).

Figure 8.1 Organization of a cable television system.

The GM directs and coordinates all system activities to ensure efficient and profitable operation within the framework established by federal law and the local franchise agreement. In particular, the general manager

• supervises and coordinates, directly or through subordinates, all personnel

• directs, through subordinates, employee compliance with established administrative policies and procedures, safety rules, and governmental regulations

• examines, analyzes, and establishes system directions and goals

• prepares and directs procedures designed to increase efficiency and revenues and to lower costs

• prepares, implements, and controls the budget

• approves requisitions for equipment, materials, and supplies, and all invoices

• represents the system to local government, business, the media, and other groups

• interfaces with the corporate office should the system be part of an MSO

As in a broadcast station, each department is unique. However, there are major differences. The cable company sends its signals through wires; the broadcast station through the airwaves. In broadcast, advertisers are the primary market. In cable, the audience is the market and the system’s financial success is tied closely to the number of subscribers it can attract and the number of services and products they purchase.

These realities impose on cable managers an obligation to ensure that the technical quality of the signal is of the highest caliber. Viewers will continue to subscribe as long as they feel they are receiving value for their money. If they do not, the system will experience subscriber disconnects. Accordingly, the marketing and technical staffs must cooperate closely, since the retention and addition of subscribers depend heavily on a signal that is technically acceptable when delivered to the home. The system manager must pay close and constant attention to those two areas of activity. They are the very foundation upon which the company survives.

The general manager must know what is happening in every department. This can be accomplished through regular meetings with department heads. Such meetings also provide an effective method of solving problems before they become crises.

Cable managers must be sensitive to the needs of their employees. Getting to know the staff, being receptive to their problems and ideas, and keeping an open-door policy will be beneficial in the smooth and effective running of the operation. Apathy and discontent also may be avoided as a result.

PROGRAMMING

The programming challenge for cable system operators has never been greater. The explosion of available program services has continued unabated. New federal laws require operators to carry certain local broadcast stations.7 Old federal laws permit or require that channels be provided for mandatory access, like PEG, and for lease by third parties. Franchise agreements may require still other channel dedication for services such as local origination. And stiff competition has arrived in the form of satellite TV companies with digital capability and a large universe of program offerings.

In addition, technological advances, including video compression and fiber optics, are rapidly expanding program choices and channel capacity. Video-on-demand, pay-per-view, and digital channels and tiers are now part of the program mix.

So, there are marketplace demands for channels and franchise and regulatory demands for channels.

It is a misconception to think that every cable television system in the United States has the capacity to be part of the 500-channel universe. In fact, about 53 percent of systems have channel capacity of between 30 and 53 channels and about another 25 percent between 54 and 90 channels. Systems with fewer than 90 channels account for more than 90 percent of cable TV subscribers.8 Marketplace and other demands fill those limited channels quickly.

Management must make program selections that satisfy subscribers’ demands for choice and value while maximizing system revenue.

Essentially, system programming is of two types: voluntary and involuntary. Voluntary operator program choices include distant broadcast signals, advertiser-supported networks, premium services, and special programming, such as PPV and VOD. Involuntary programming may include local broadcast stations under the must-carry rules, PEG mandatory access, leased access, and local origination.

Once chosen, programming must be paid for. Most voluntary programming requires payment; most involuntary programming does not. System operators pay for programming in two ways. The first is a requirement of federal law. In 1976, Congress enacted a comprehensive copyright law that required cable systems to pay semiannual fees for the carriage of some television stations. Copyright fees are not owed for carriage of local stations under must-carry. However, a compulsory fee set by law is required to carry distant commercial stations, including superstations.

In addition to the copyright payment, most voluntary program selections involve a payment directly to the program supplier. Such payments normally are calculated on a per-subscriber basis and are influenced by system size, since volume discounts are offered. There may be surcharges for some networks, especially those that offer professional sports, such as ESPN and TNT. In those instances, the programmer passes along to the cable system part of the substantial rights fee for such programming. However, many advertisersupported cable networks allow systems to sell local advertising in network programming. This local revenue generation helps to offset the programming cost. As noted earlier, local ad sales are becoming significant.

Costs for noncommercial premium channels, like HBO, are far different. Payments are also set on a monthly, per-subscriber basis, but the amounts are much higher than for commercial, advertiser-supported networks. Again, volume discounts are offered. Obviously, no commercial offset for local system revenue generation is possible. Consequently, subscriber charges for premium channels are also much higher than those for basic sources.

Some program decisions result in payments to the cable system. Home shopping networks, for example, pay local systems a percentage of gross product sales generated in the system’s franchise area. New networks often provide systems with financial marketing support to assist their launch in the community. However, the sums are not large.

It has been emphasized that the audience is the major customer of cable television and provides its principal financial support. For that reason, an important economic consideration in all programming decisions is the anticipated impact on subscriptions. A major goal in program selection is the addition of subscribers and the minimizing of disconnects. Decisions to accomplish those goals will rely on the operator’s familiarity with the composition and program preferences of the community and of subscribers and nonsubscribers.

The operator’s expertise in program selection is very important. It was noted earlier that cable systems pass 97 percent of the nation’s television households, but that only about 67 percent of those homes subscribe. Attractive program choices must be available to convert some of the nonsubscribing homes to subscribers.

Recognizing the potential and limitations of the system’s technology, legal obligations contained in federal law and the franchise agreement, and the need to maximize audience appeal and ensure a profit, the operator proceeds to program the available channels. Typically, the services provided include the following:

Local Origination and Access Channels

Many systems are required by the franchise agreement to produce programs for carriage on local origination, or community, channels. Time, temperature, and newswire displays, round-table discussions, and local sports are examples. Some also use the channel for community bulletin boards and program previews. In all cases, operators control the content.

The agreement also may require that channels be reserved for public, educational, and governmental access. This programming is produced by persons outside the cable company and often includes discussions, credit and noncredit courses, and meetings of local government bodies.

As noted earlier, some systems are required to offer leased access to individuals or groups. The content varies widely, reflecting the interests and goals of the leasing parties.

Most systems add audio to the service mix. Local radio stations are an example. Many also carry digital audio programming with several dozen channels of specialized music.

Local, Over-the-Air Broadcast Stations

The 1992 Cable Consumer Protection and Competition Act reimposed must-carry rules on the cable industry.9 Simply put, “must-carry” requires a cable system to carry the commercial and noncommercial stations in its area. Under the law, broadcasters were required to choose between mustcarry or retransmission consent before October 6, 1993. Retransmission consent is a legal alternative to must-carry. If a station elected retransmission consent, that amounted to a must-carry waiver. Under retransmission consent, broadcast stations could not be carried on a cable system without their consent. If a station and system could not reach a retransmission agreement, the system was free to drop the station in question.

The 1992 law considerably reduces programming discretion by a cable operator with respect to local television stations. More details on the specifics of must-carry may be found in the regulation section later in the chapter.

Distant Broadcast Stations

So-called “superstations,” such as WGN (Chicago) and WTBS (Atlanta), offer entertainment and sports programming that may not be available from other sources. The system pays to the stations a small, monthly subscriber fee.

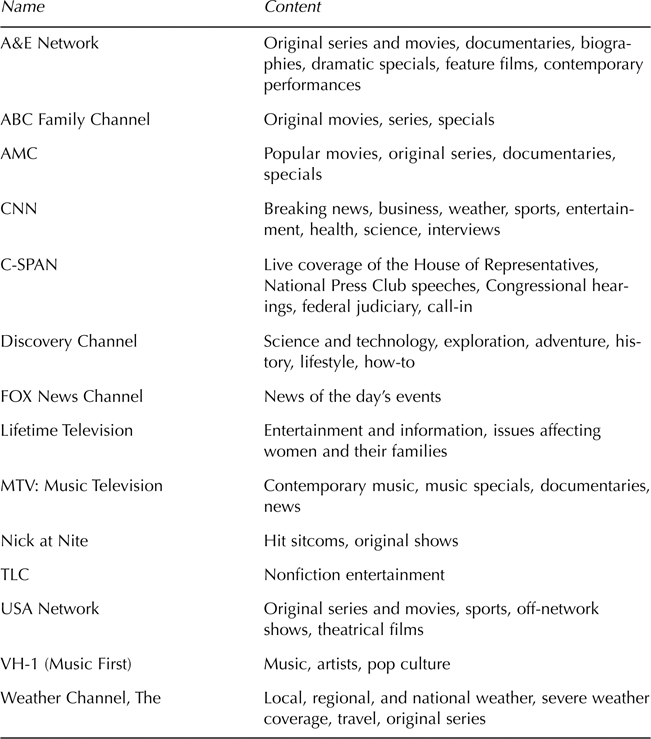

Basic Cable Networks

Operators have a large universe of basic networks from which to choose. Some target a narrow audience with specialized content, while others seek a broader audience with more diverse programming (Figure 8.2). Together, the networks provide a range of programming, and their selection will reflect the operator’s perceptions of the interests and needs of the community and its subgroups. Compensation arrangements for system carriage of these mostly advertiser-supported networks were reviewed earlier in the chapter.

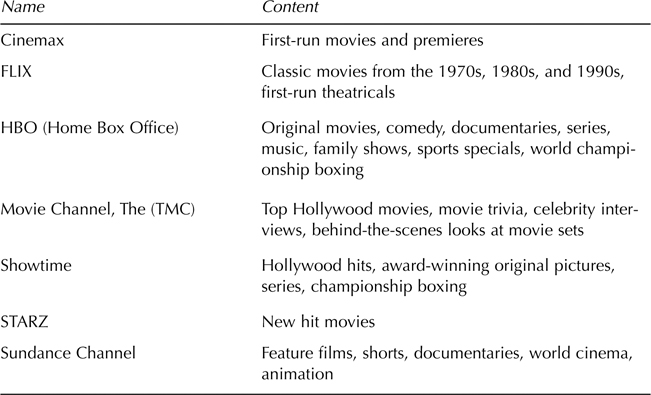

Pay-Cable Networks

These networks (Figure 8.3) offer commercial-free entertainment for a monthly subscriber fee, part of which is retained by the cable company. As a result, these so-called “premium” channels are a high economic priority for operators.

Figure 8.2 Selected basic cable networks and their content.

Figure 8.3 Selected pay-cable networks and their content.

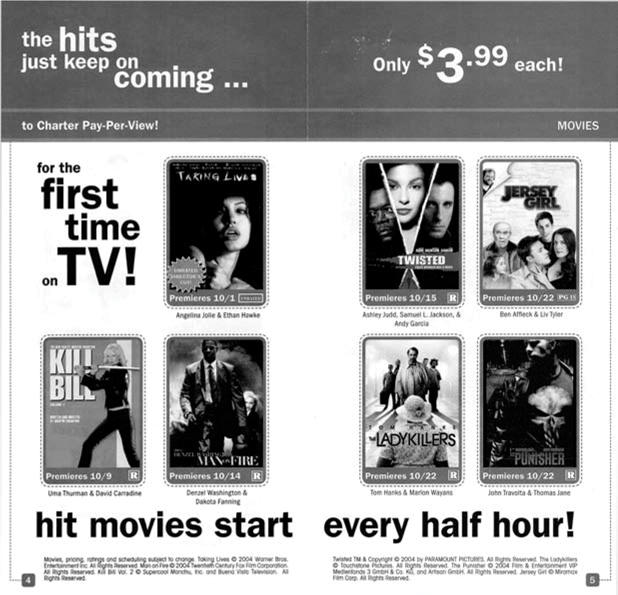

Some systems are using channel space for their own newscasts and for system-purchased syndicated programming, previously the exclusive domain of network affiliates and independents. Those with the necessary technology are reserving channels for PPV programming, which permits subscribers to select special programs, such as sports or entertainment specials, for which they are billed separately. Individual systems may contract for the rights to carry a PPV event or to acquire programs from one of several national PPV services. For an example of a PPV marketing piece, see Figure 8.4.

Figure 8.4 Excerpt from a PPV marketing piece.

(Source: Charter Communications. Used with permission.)

Still other channels are being dedicated to the emerging VOD market, which has become a significant revenue source. Video-on-Demand provider iN DEMAND reported that, starting around June 2004, Movie-on-Demand orders exceeded those for PPV by more than two-to-one.10

Programming is a key contributor to successful operation. Without appealing programs, there would be no subscribers. Without subscribers, there would be no system. Providing a balanced program service at an acceptable cost is a continuing challenge.

TIERING

Once the operator has made all the programming choices, attention will turn to marketing the selected products. Historically, cable systems have bundled certain categories of programming together for sale to potential subscribers. That practice is known as tiering. Typically, the subscribers’ fee structure is tied to the tiers, and the total monthly charge depends on the options chosen.

There has always been a relationship between tier structure and government regulation, both federal and local. The best current example of the relationship is the massive change in tiering that resulted from the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992. The law required cable systems to establish a separate basic tier and specified what must be included in it.11 The minimum requirements include all must-carry stations, distant television stations carried by the system, excluding superstations, home shopping stations,12 and mandatory access channels. Most systems call this “basic” or “limited basic.” Rates for this government-mandated tier are regulated by the local franchise authority. Details of rate regulation appear later in the chapter.

The basic tier requirement, and the rate control that went with it, caused a significant realignment of the structures that existed before the 1992 law. Operators had to create a new home for those program sources that were subject to price increases or surcharges. Because of government-imposed basic rate control, operators could no longer easily pass along to subscribers program costs for existing sources or for new sources.

As a consequence, most of the nation’s almost 9,000 systems have established some form of expanded basic tier. Expanded basic or expanded service, as some call it, usually includes the non-must-carry, non-premium services that existed previously in the old basic tier. Here are found primarily the advertiser-supported networks. Typical expanded basic offerings would include CNN, USA, MTV, and A&E, for example.

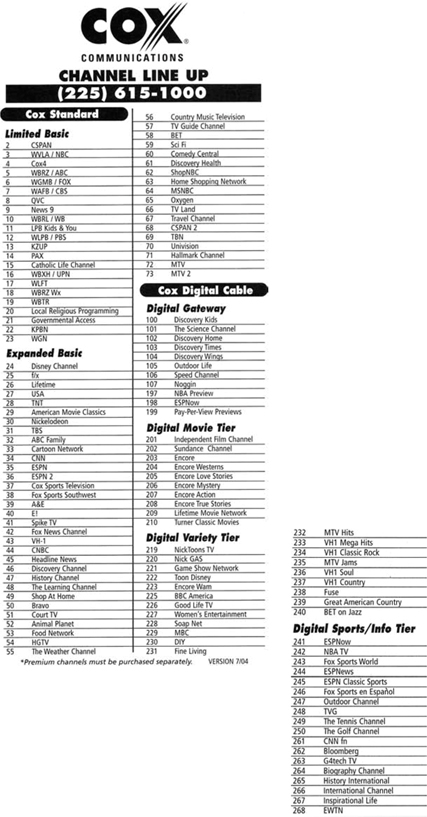

The new tiering plans also have premium levels beyond the expanded basic service. This is where digital has had a big impact. Digital cable is in more than 30 percent of cable homes and increasing rapidly, from 6 million to 25 million since 2000.13 MSOs create program tiers by genre, such as sports, music, movies, family, and Spanish programming. For an example, see Figure 8.5.

Figure 8.5 Cable tiers.

(Source: Cox Communications. Used with permission.)

Whether the system is analog or digital, beyond expanded basic are positioned the standard, premium noncommercial program services. Such offerings might include HBO, Showtime, Cinemax, The Movie Channel, and The Disney Channel. These premium channels may be subscribed to on an individual or package basis.

ECONOMICS

The new century has seen an end to cable’s build-out phase. With virtually all TV households passed by cable and satellite gaining new subscribers every day, cable’s revenue growth no longer will come principally from adding new subscribers. Emphasis now is on digital conversion and the addition of new services.

Cable enters this stage with more than 73 million basic subscribers and 50 million premium subscribers. In addition to subscriber revenue, cable adds income from digital music channels, DSL, high-speed Internet, telephone, and the sale of advertising time.

Revenues

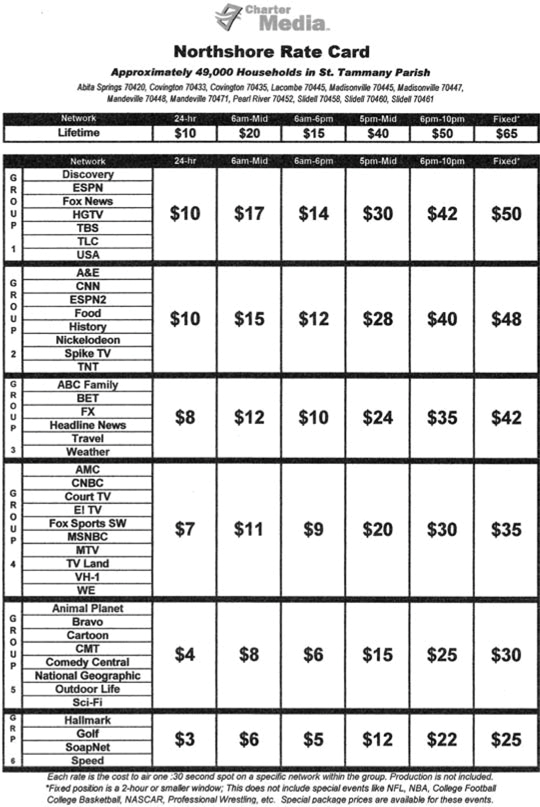

It is the responsibility of the system’s marketing department to recruit subscribers. Figure 8.6 illustrates how the marketing process works for the program services listed in Figure 8.5.

Figure 8.6 Tier pricing.

(Source: Cox Communications. Used with permission.)

Note that the limited basic tier listed on the top of the channel lineup in Figure 8.5 is not listed on the price sheet in Figure 8.6. It is included in Cox Standard, which is really expanded basic. After that, the marketing effort focuses on the program genre tiers noted above. The “Supersize” is “Digital Deluxe,” where customers get it all for a discount, $53.01.

One technique formerly employed by cable system marketers is no longer available. Before the 1992 cable law, subscribers were required to buy through one tier to get to the next. For example, they had to purchase expanded basic to obtain premium services. The law prohibits buy-through requirements, except for the government-mandated basic channels.

A cable system’s revenues are not limited to regular video program services. Pay-per-view and digital audio also contribute to an operator’s gross revenue. Installation, reconnect, and change of service charges, together with equipment rental (e.g., remote controls, addressable converters), add incremental income.

If revenues are to be enhanced, cable managers must continue to pay close attention to subscriber needs and provide prompt, efficient, and courteous service. One study of almost 1,800 subscribers and nonsubscribers concluded that good service equates with good value and poor service with poor value, regardless of the rates charged.14

Many systems have installed telephone automatic response units (ARUs) so that questions may be channeled directly to the appropriate information source. Allied with computers, the units permit subscribers to check their account balance and the date and amount of their last payment, order special movies or events, report a service problem, confirm or reschedule a service or installation appointment, and receive general information.

Important as technology is, its contribution may be limited by the personnel assigned to it. Accordingly, customer service representatives (CSRs) must be trained in its use and must understand the importance of customer satisfaction. A dissatisfied customer may mean one fewer subscriber and a lost revenue source. Telemarketing assistants must be informed, but not aggressive and dictatorial.

Similarly, company employees who come face-to-face with customers and prospective customers must be knowledgeable and skilled in human relations. Installers and service technicians must be aware of the subscriber’s needs, take appropriate steps to avoid damage to property, and be tolerant in explaining and responding to questions about the operation of cable in the home. Door-to-door sales representatives must be suitably dressed and act in a professional manner.

The importance of cable to subscribers is exemplified when a storm or other event interferes with service. Typically, the system’s telephone lines are jammed with calls and the temperament of the CSRs is put to the test. Patience and a sympathetic attitude can do much to disarm customers’ annoyance and to reassure them that the problems are being resolved. On such occasions, however, frankness is mandatory. Only realistic estimates of service resumption time should be given. If wild and unsubstantiated guesses are made and not fulfilled, annoyance will grow into anger and, possibly, more lost customers and revenue.

Advertising is becoming an increasingly significant revenue source. As noted earlier, local spot was expected to reach $6 billion in 2005. Multiple system operators have been especially aggressive in developing this source. Often, they interconnect individual systems in contiguous geographic areas to deliver more homes to advertisers. Some large metropolitan systems owned by different operators may interconnect for the purpose of marketing local and spot announcements.

Cable has several advantages for advertisers. It attracts audiences that are characterized as better-educated and more affluent than the average TV viewer. The special-appeal programming of many basic networks permits the targeting of specific demographics, much like radio. In addition, time is less costly than on a broadcast television station. However, the quality of ads produced only for cable often is inferior, and the automated hardware to run them is expensive and often unreliable.

Time is sold on local origination channels and on many expanded basic networks. The majority of networks make available time for local sale. Figure 8.7 shows the rate card for a system operated by Charter Communications.

Figure 8.7 Local spot rate card.

(Source: Charter Communications. Used with permission.)

The knowledge, skills, and personal qualities of the advertising sales manager and the account executives, and the sales tools necessary for success, are similar to those required of their broadcast counterparts, described in Chapter 5, “Broadcast Sales.”

Historically, cable systems have not been preoccupied with ratings. What was important was that subscribers signed up and enjoyed their viewing experiences enough to continue their subscription. Now that advertising is becoming a more important revenue source, systems are more ratings-conscious. To assist them, Nielsen has developed the Nielsen Homevideo Index (NHI), which measures audiences for basic and pay services. The company also undertakes specially commissioned studies for operators.

Reliable audience information is a necessity if local ad sales are to continue their growth and operators are to make informed decisions in selecting programs with appeal to audiences and to the advertisers that seek them.

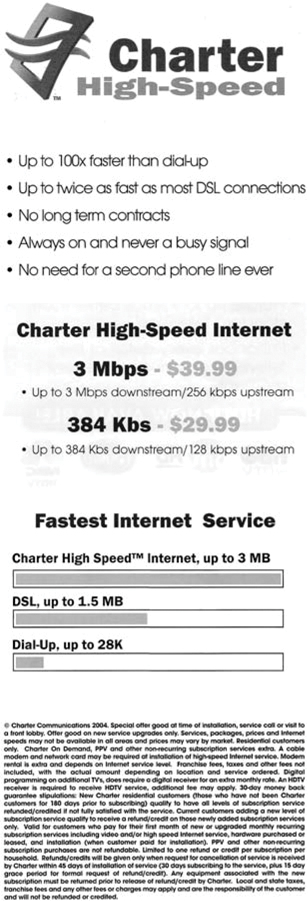

High-speed Internet Access

Many cable systems provide high-speed Internet service to compete with the DSL provided by some telephone companies, such as BellSouth, Qwest, and Verizon. Cable enjoys the competitive advantage: its service is faster than DSL.

Cable has about twice the number of high-speed Internet access customers than DSL providers. Since cable high-speed Internet service penetration is only about 27 percent of cable homes, it has a lot of room to grow. See Figure 8.8 for an example of how a high-speed Internet provider markets the service.

Figure 8.8 Excerpt from a high-speed Internet marketing piece.

(Source: Charter Communications. Used with permission.)

Telephone Service

Cable is offering circuit-switched telephony services to both residential and business subscribers. This business is in its infancy for cable companies and has significant growth potential. Further, cable is experimenting with voice-over Internet protocol (VOIP). This service has unlimited local and long-distance service, caller ID, call waiting, call return, three-way calling, call forwarding, and emergency 911 service. The service is priced modestly on a trial basis, $34.95 in the New York City area, and also has development potential.

Music Services

Access to licensed music, such as ASCAP, BMI, and SESAC, has become another revenue source for cable TV systems. An example is Real Networks’ Rhapsody Jukebox subscription service. It provides access to over 30,000 albums produced by the 5 largest music companies and 200 smaller labels.

Digital Video Recorders

Cable also markets products. One example is the successful launch of digital video recorders (DVRs). This product empowers the subscriber to record programming onto a hard drive. The technology enables the viewer to pause live programs and fast-forward recorded content. Customer appetite appears to be strong, and Time-Warner has deployed DVR service nationwide.

Expenses

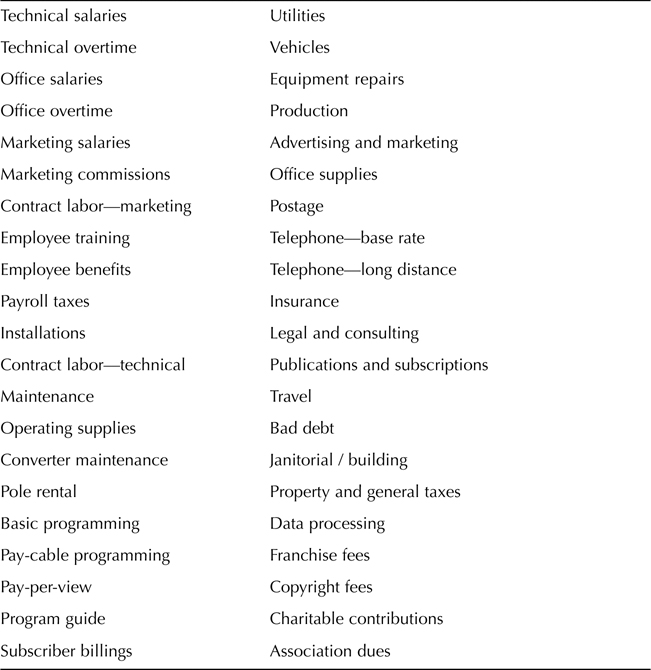

In addition to paying regular taxes, cable television systems are required to hand over to the franchising authority up to 5 percent of their revenues and, in some cases, channel capacity for public, educational, and governmental use.

The cost of laying cable, converting to digital, and adding new services is a substantial investment for a business that must share its revenues with the community. The investment becomes even larger if the cable company has agreed in its franchise to originate local programming and has to equip a production facility.

Many of the system’s operating expenses are similar to those of a broadcast station: salaries, commissions, employee benefits, payroll taxes, utilities, supplies, programming, travel, and communication. Major differences are the franchise fees described above, maintenance and repair of miles of cable and associated equipment, and pole rental. Principal expense items are listed in Figure 8.9.

Figure 8.9 Cable TV system expense items.

Like the broadcast manager, the cable manager faces a difficult task in trying to increase revenues and control costs in a very competitive marketplace. With the advent of direct broadcast satellite (DBS) competition and the conversion to digital cable, operators’ programming expenses have exploded. Annual increases are far ahead of the inflation rate. Since 1992, they have increased almost four-fold. Consumers have many options in spending their entertainment and information dollars. Likewise, advertisers have a choice of vehicles for marketing their products and services. Careful attention to the needs of both groups, and appealing and economically attractive responses, are imperative.

PROMOTION

Cable promotion has begun to reflect the maturity of the business itself. The original elements are still there, to be sure. Systems continue to use direct mail, door-to-door, and on-the-air solicitations. Most systems have a dedicated program-listing channel. Other techniques are being employed as well. Principal among them is over-the-air television. Local TV stations once were reluctant to accept cable advertising, since the two were seen to be in direct competition for audiences. For the most part, that reluctance is gone and systems, individually or as part of an area marketing group, use broadcast television extensively. The results are impressive. People who watch television are, after all, a logical market for cable systems.

Radio is attractive, too. It is cost-effective, and advertising can be targeted to the unique formats and demographics of stations.

Newspaper is used successfully, particularly to feature coupons for a premium service at an introductory rate and with no installation cost. Program listings in the newspaper’s television program supplement, in cable guides, and in TV Guide also are forms of valuable promotion.

Many systems use a monthly program guide to carry listings and interest subscribers in upgrading their service. Some employ a basic channel, called a barker channel, to promote premium services and pay-per-view.

Promotion costs can sometimes be offset by co-op money from the national cable networks, and system managers need to know how to access such funds.

Promotion sophistication for the system will increase as the battle for subscribers and advertisers continues to intensify. As a result, it will become a critical skill for cable management.

There are professional organizations that can assist. One is the Cable & Telecommunications Association for Marketing (CTAM).

REGULATION

Since its inception, cable has been an irritant to the FCC. To begin with, it was not an area of federal prerogative. Regulatory responsibility has always been shared with local authorities, whose streets and rights-of-way are essential for a cable system’s operation.

The giant cable industry of today was not even contemplated when the 1934 Communications Act was written. Consequently, federal regulation of cable was done on an as-needed basis by the FCC. Courts and the FCC, alike, wrestled with rationales for tying regulation into the framework of the act. The commission’s jurisdiction was confined to system operational matters; franchising was left to local authorities.

Historically, the principal motivation for regulation of cable was its status as an unregulated monopoly with no effective competition. With today’s strong competition from DBS and other multichannel video providers, that rationale has largely faded. Cable now seeks protection from competition. For example, the industry is striving for relief from an FCC rule that requires operators to offer uniform pricing throughout a franchise area. Cable asserts that, since DBS has significant household penetration, effective competition now exists. Accordingly, it should be freed from pricing regulation that was justified on the grounds that it was a monopoly.15 Regulators’ attitudes toward cable today are quite different from the initial reaction.

The initial FCC cable regulatory motivation was to protect licensed television broadcasters from the perceived threat of cable. The threat took two forms: first, cable’s ability to reduce locally licensed stations’ audiences and revenues by importing out-of-market signals; and second, its retransmission of expensive local broadcasters’ programming without compensation.

As noted previously, the FCC first attempted to deal with its cable concerns under imputed authority derived from the 1934 act. By 1984, cable had grown to the point that it was able to demand, and receive, explicit regulatory status from Congress. That law was the Cable Communications Policy Act of 1984, which deregulated cable. However, industry stewardship of its deregulated status was not successful in the eyes of many consumers and Congress. In response, Congress passed the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992.

To combat the first threat, the importation of out-of-market signals, the FCC enacted signal carriage rules. They took three forms: must carry, network nonduplication, and syndicated exclusivity. The second problem, noncompensation to local broadcasters, was addressed to some degree by Congress in the Copyright Act of 1976 and in the 1992 Cable Consumer Protection and Competition Act.

All the signal carriage rules of the FCC have had many reincarnations, but none more than the must-carry rules. As noted earlier, must-carry requires a cable system to carry the commercial and noncommercial television stations in its area. These long-standing rules were struck down on First Amendment grounds in two court decisions in the mid-1980s. Broadcasters’ attempts to restore them were finally achieved in the 1992 Act, but they were challenged in the courts. In 1997, however, the Supreme Court upheld their constitutionality in a 5-4 decision.

The 1992 must-carry rules apply to carriage of both commercial and non-commercial television stations. The principal requirements are as follows:

• Systems with more than 12 channels must set aside up to one-third of their channel capacity for local signals.

• Home shopping stations are entitled to must-carry, as are qualified low-power television (LPTV) stations.

• Systems with 12 or fewer channels must carry 1 local noncommercial station; systems with 13 to 36 channels may be required to carry up to 3 local noncommercial stations; and systems with more than 36 channels may be required to carry more than 3 local noncommercial stations, if the programming of the additional stations does not substantially duplicate the content of the other stations.

It was noted earlier that the 1992 law allows stations to select a retransmission consent option in lieu of must-carry. Stations that opt for retransmission consent must negotiate with local cable systems for channel position and compensation. If the negotiations are unsuccessful, a local station might end up with no system carriage at all for three years.

A second FCC signal carriage rule is network nonduplication, or network exclusivity. It prohibits a cable system from carrying an imported network affiliate’s offering of a network program at the same time it is being aired by a local affiliate.

The third significant carriage rule involves syndicated program exclusivity, known as syndex. Prior to 1980, the FCC protected a local station’s syndicated programs against duplication in the market from distant signals imported by cable systems. In 1988, the FCC reinstituted the rule, but delayed its implementation until January 1, 1990. The rule allows a local station with an exclusivity provision in its syndicated program contract to notify local cable systems of its program ownership. Once notified, the system is required to protect the station against duplication from imported signals, including those of pay and nonpay cable networks.

The other principal FCC concern about the emerging cable industry was the question of compensation of broadcasters for retransmission of their signals by cable. The controversy finally was resolved in 1976, when a new copyright law was passed. Under the law, cable TV was to pay royalties for transmission of copyrighted works. These revenues were in the form of a compulsory license paid to the Registrar of Copyrights for distribution to copyright owners.

According to the provisions of the law, cable operators must pay a copyright royalty fee, for which they receive a compulsory license to retransmit radio and television signals. The fee for each cable system is based on the system’s gross revenues from the carriage of broadcast signals and the number of distant signal equivalents, a term identifying non-network programming from distant television stations carried by the system.

The law requires a cable operator to file semiannually a statement of accounts. Information in this report includes the system’s revenue and signal carriage, as well as the royalty fee payment.

The law also established a now-abolished Copyright Royalty Tribunal (CRT), composed of five commissioners, to distribute the royalty fees and resolve disputes among copyright owners and to review the fee schedule in 1980 and every five years thereafter. The CRT administered three funds: (1) the basic royalty fund; (2) the 3.75 percent fund established to compensate copyright owners for distant signals added after June 24, 1981; and (3) the syndex fund. Changes in the funds administered and the amounts collected have occurred as the FCC and Congress have altered the signal carriage rules. The abolition of the CRT had no effect on copyright fees owed, or on cable system reporting requirements.

The 1992 cable law did much more than restore must-carry. Essentially, it reregulated cable. Of special significance was the act’s reintroduction of rate regulation, which had been abolished in 1986. The period of deregulation saw an explosion of system rates, with resulting pressure on Congress by angry subscribers. Rate regulation ended with the Telecommunications Act of 1996. It contained a sunset provision for rate regulation in 1999.

WHAT’S AHEAD?

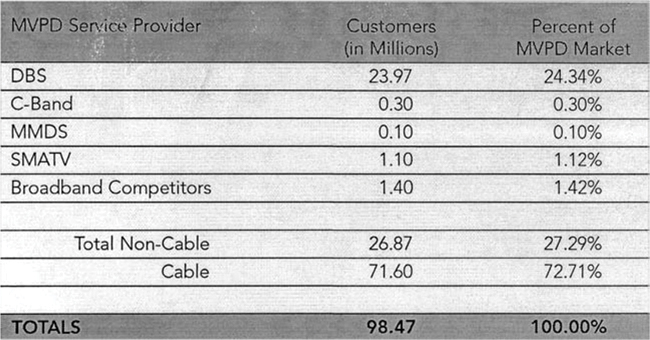

The future of cable can be summed up in one word: competition. It has arrived—DBS, wireless cable, telephone and utility companies, and others. Indeed, any business with a fiber network in place may emerge to challenge cable systems that formerly enjoyed a virtual monopoly (Figure 8.10).

Figure 8.10 Analysis of multichannel video program distributors(MVPDs).

(Source: 2004 Year-End Industry Overview, p. 21. http://www.ncta.com. Used with permission.)

DBS has become an especially strong foe. Attracted by low-cost dishes and local station carriage, DBS households increased ten-fold between 1993 and 2003, to 19.5 million and a market penetration of 23.51 percent. The number of subscribers continues to rise and, by mid-2005, had reached more than 25 million. In the face of this intense competition, cable percentage penetration of the video provider market is no longer growing.

Cable television operators have not thrown up their hands, however. In fact, media investment analysts correctly anticipated continuing cable prosperity into the early years of the twenty-first century, sparked by some of the same technologies that have resulted in the intensified competitive environment in which the industry finds itself. Cable has found and is developing new services and products. The industry has just scratched the surface of high-speed Internet, telephone, digital tiering, DVRs, and music channels.

With all this has come a quantum increase in cable’s program performance with audiences and acceptability by advertisers. Statistical analysis suggests that these trends are likely to continue. And with all that will come continuing revenue and profitability growth.

The cable industry is largely consolidated now. Eight multiple system operators have 75 percent of subscribers. The build-out and consolidation phase is largely over.

Cable has demonstrated its ability to thrive in a world of intense competition. It emphasizes the market advantages it possesses. Digital conversion and the development of new products and services indicate that the industry’s best years are ahead. With its energies spent on business development and not on responses to angry regulation, cable is on the high-speed digital path to increased success.

SUMMARY

Cable is hardwired and requires rights-of-way over and under city streets to gain access to viewers’ homes. Because of this unique requirement, cable systems are licensed by local governments. The licenses are called franchises, and they have to be renewed at intervals set forth in the franchise agreement.

Cable television systems are run by general managers, who answer to ownership. Reporting to the general manager are the heads of departments with clearly identified responsibilities. Usually, they include government affairs and community relations, human resources, business operations, advertising sales, technical operations, marketing, and customer service.

Programming decisions take into account technological, legal, and audience-appeal and associated economic factors. Program sources include local origination and access channels, local and distant over-the-air television stations, and basic and pay-cable networks. Many systems also offer special programs on a PPV and VOD basis. Typically, program services are bundled into tiers and are priced accordingly.

Initially, cable revenues consisted almost entirely of monthly subscriber fees. As the industry has matured, it has developed other revenue sources, including the sale of local advertising, and digital and other devices, such as high-speed Internet, telephone, music channels and DVRs. Pay-per-view and VOD also contribute to revenue enhancement. Operating expenses are similar to those of broadcast stations, but with some notable differences. Systems must pay to the local franchise authority a franchise fee of up to 5 percent of their gross revenues. They are also required to meet the cost of maintaining and repairing miles of cable and allied equipment, and of renting poles on which to string the cable.

Promoting the varied program services available is a high priority in attracting and retaining subscribers. Among the most effective promotional tools are door-to-door and direct-mail marketing, local television and radio stations, newspapers (especially the television program supplement), and the system’s own channels. Successful managers should be involved in professional promotion and marketing organizations like CTAM.

Cable systems are required to carry, or obtain retransmission consent from, local commercial and noncommercial television stations. Many systems also have to provide PEG mandatory access and/or local origination channels. New competitors are entering the video distribution marketplace, and they pose major challenges to the cable industry. In turn, cable operators have attracted subscribers to a range of new communication services.

CASE STUDY

James Dean has inherited a 90-channel analog cable TV system from a favorite uncle. Uncle Dean had begun the system in 1968 after graduation in electronics from Bayou University in Thibodaux, Louisiana. The old man was interested mostly in electronics and technology. As a consequence, he was on top of industry trends but not adept at marketing his system. At the time of his death, Dean the elder had signed a contract to convert to a digital system and had funds in the bank to begin construction.

James wanted to be a movie star but gave up the idea and was looking for a career. He had received a degree in telecommunications before his acting misadventure in Los Angeles. He would like to develop his inherited cable business but is nervous about its spotty revenue and profit history. As he gazes out of his late uncle’s office window after the funeral, he notices that a DBS sales office has opened in part of the telephone building next to its new DSL service directly across the street.

He faces a dilemma: should he retain the system or would he be better off if he were to sell it and take the money to the bank?

EXERCISES

1. What pro-active actions could James take to develop the business and enhance revenue and profits?

2. What personal activities could James undertake to enhance his ability to succeed if he retains the business?

3. Is continued operation of the business just too risky given the new competition across the street in the form of a new DSL business by the phone company and the new multichannel video company in the form of DBS?

4. Should James go back to attempting to make movies and distribute them on the cable system to attract subscribers?

NOTES

1 Industry Statistics, http://www.ncta.com.

2 2004 Year-End Industry Overview, p. 13, http://www.ncta.com.

3 Industry Statistics, http://www.ncta.com.

4 City of Los Angeles v. Preferred Communications, 106 S.Ct. 2034, 1986.

5 47 USC 546.

6 47 USC 546(c)(1)(A–D).

7 47 USC 534, 535.

8 Television and Cable Factbook 2003, p. F-2.

9 47 USC 534, 535.

10 2004 Year-End Industry Overview, p. 7, http://www.ncta.com.

11 47 USC 543.

12 Kim McAvoy, “Home Shopping Gets Must Carry,” Broadcasting & Cable, July 5, 1993, p. 8.

13 Industry Statistics, http://www.ncta.com.

14 “Service Showing,” Broadcasting, February 5, 1990, p. 86.

15 “Capital Watch,” Broadcasting & Cable, September 20, 2004, p. 26.

ADDITIONAL READINGS

Bartlett, Eugene. Cable Communications: Building the Information Infrastructure. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1995.

Covington, William G., Jr. Creativity in TV & Cable Managing and Producing. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1999.

Crandall, Robert W., and Harold Furchgott-Roth. Cable TV: Regulation or Competition? Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1996.

Creech, Kenneth C. Electronic Media Law and Regulation, 4th ed. Boston: Focal Press, 2003.

Eastman, Susan Tyler, and Douglas A. Ferguson. Media Programming: Strategies and Practices, 7th ed. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2006.

Eastman, Susan Tyler, Douglas A. Ferguson, and Robert Klein (eds.). Promotion and Marketing for Broadcasting, Cable and the Web, 4th ed. Boston, MA: Focal Press, 2001.

Parsons, Patrick R., and Robert M. Frieden. The Cable and Satellite Television Industries. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1998.

Understanding Broadcast and Cable Finance: A Handbook for the Non-Financial Manager. Northfield, IL: BCFM Press, 1994.

Warner, Charles, and Joseph Buchman. Media Selling: Broadcast, Cable, Print and Interactive, 3rd ed. Ames: Blackwell, 2003.