5

Broadcast Sales

This chapter considers

• the functions of the sales department and the responsibilities and attributes of its personnel

• the sale of time to local, regional, and national advertisers

• research methods and the uses of research in sales

A broadcast station serves two kinds of customers:

• Audiences, which tune to a station to hear or view its programs and which make no direct payment for the product (i.e., programs) they receive. As we have seen, obtaining audiences is the responsibility of the program department.

• Advertisers, who gain access to those audiences with information on their products and services by purchasing advertising time. Obtaining advertisers is the responsibility of the sales department.

Broadcast advertisers fall into three categories:

• Local: Those in the immediate geographical area of the station.

• Regional: Those whose products or services are available in the area covered by the station.

• National: Those whose products or services are available nationwide, including the area covered by the station.

Time is sold to local and regional advertisers by members of the station’s sales staff called account executives. Sales to national advertisers are carried out by the station’s national sales manager or by its national sales representative, known as the station representative (station rep) company.

The sales department is the principal generator of revenues for the station. However, its ability to sell time is determined to a large degree by the program department’s success in drawing audiences, especially those that advertisers want to reach. Good programming attracts audiences, which in turn attract advertisers and dollars. The greater the sales revenues, the better the programming the station can provide. Together, therefore, the program department and the sales department are important parts of a cycle that has a major impact on the station’s financial strength.

THE SALES DEPARTMENT

The number of sales department employees of a particular station is influenced largely by market size. Local competitive conditions also may be influential. However, departments in markets of all sizes have similar responsibilities.

Functions

The major functions of the sales department are to

• sell time to advertisers

• provide vehicles whereby advertisers can reach targeted audiences with their commercial messages at a competitive cost

• develop promotions for advertisers

• generate sufficient revenues to permit the station to operate competitively

• produce a profit for the station’s owners

• contribute to the worth of the station by developing and maintaining a strong base of advertiser support

Organization

The staff and activities of the department are directed by a general sales manager (GSM), who answers to the general manager and whose specific responsibilities are described later. The following are the principal department staff:

National Sales Manager

Coordinating the sale of time to national advertisers through the station rep company and maintaining contacts with local offices of national accounts are the chief responsibilities of the national sales manager, who reports to the general sales manager. In many stations, the duties are carried out by the general sales manager.

Local Sales Manager

The local sales manager reports to the general sales manager and is responsible for

• planning and administering local and regional sales

• directing and supervising account executives

• assigning actual or prospective clients to account executives

• establishing account executive sales quotas

• in some stations, carrying a list of clients

Account Executives

Account executives report to the local sales manager and

• seek out and develop new accounts

• service existing accounts

• prepare and make sales presentations

• in radio, often write and produce commercials

Co-op Coordinator

Many manufacturers reimburse retailers for part of the cost of advertising that promotes the manufacturer’s product. This arrangement is known as cooperative, or co-op, advertising, and stations often employ a coordinator to provide co-op data to account executives. However, the responsibilities may be more extensive and may consist of

• identifying co-op opportunities

• working with retailers in the development of co-op campaigns using advertising allowance credits, called accruals

• handling the various elements of the campaign, such as copy and production, and overseeing the campaign’s execution

• assisting retailers in filing for reimbursement of co-op expenditures

In many stations, the co-op coordinator’s job has evolved to include vendor support programs. They will be discussed later in the chapter.

Once sales orders have been received and checked by the sales manager, they are confirmed and processed. Those are among the responsibilities of the traffic department, which often is a unit of the sales department. It is headed by a traffic manager, who reports to the general sales manager. The traffic department also

• prepares the daily program log detailing all content to be aired, including commercials

• maintains and keeps current a list of availabilities, called avails—in other words, time available for purchase by advertisers

• advises the sales department and the station rep company of avails

• schedules commercials and enters appropriate details on the program log

• checks that commercials are aired as ordered and scheduled

• advises the general sales manager if commercials are not broadcast or are not broadcast as scheduled, and coordinates the scheduling of make-goods

Clients who do not use the services of an advertising agency often require the station’s assistance in writing and producing commercials. The writing usually is assigned to copywriters in the continuity or creative services department, which may be a unit of the sales or program department and which is headed by a director. Commercial production is carried out by the production staff.

THE GENERAL SALES MANAGER

Responsibilities

Like all managers, the general sales manager plans, organizes, influences, and controls. The proportion of time spent on those and other functions varies. In a large station, for example, the position may be chiefly administrative. In a smaller station, the general sales manager may be a combination national and local/regional sales manager and account executive. However, included in the major responsibilities of most general sales managers are the following:

• Developing overall sales objectives and strategies. They are drawn up in agreement with the station rep and national sales manager for national sales, and with the local sales manager for local and regional sales.

• Selecting the station representative company, in consultation with the general manager and the national sales manager.

• Preparing and controlling the department’s budget, and coordinating with the business department collections, the processing of delinquent accounts, and credit checks on prospective clients.

• Developing the rate card and controlling the advertising inventory.

• Selecting, or approving the selection of, all departmental personnel and arranging for their training, if necessary.

• Setting and enforcing sales policies, and reviewing all commercial copy, recorded commercials, and sales contracts.

General sales managers engage in a variety of other duties, including the conduct of sales meetings, approval of account executive client lists, and the handling of house accounts, or accounts that require no selling or servicing and on which no commissions are paid. However, one of their most significant activities is the establishment of sales quotas.

The importance of revenue and expense projections in the preparation of the station’s annual budget was noted in Chapter 2, “Financial Management.” As the major generator of revenues, the sales department plays a key role in the station’s success. If its projections are unrealistic and fall short of expectations, cost-cutting measures will have to be introduced to keep the budget in balance. Those measures might include the termination of personnel and the modification or elimination of plans for equipment purchases, programming, promotion, and other areas of station operation.

To try to avoid such an upheaval, most sales departments establish attainable annual dollar targets. In many stations, account executives are asked to submit their sales goals for each month of the next fiscal or calendar year, reflecting adjustments for the number of weeks per month compared to the current year and the proposed percentage increase. The GSM and the local sales manager review them, determine their appropriateness, and make changes they deem necessary. Finally, the sales managers meet with each account executive and, together, the three agree on a final quota. In the meantime, the GSM consults with the station rep to settle on targets for national sales.

When these steps have been completed, the GSM sends to the general manager the department’s budget proposal listing projected revenues from local, regional, and national sales and estimated expenses. It is analyzed with the submissions from other departments, and adjustments are made to develop a balanced budget. They may consist of a reduction in requested expenditures, an increase in revenues, or both. If more revenues are called for, the GSM considers the options with the local sales manager, account executives, and the station rep, and higher goals are established by mutual agreement.

Monthly goals provide continuing, short-term targets. They may not always be met. A delay in receipt of an order, a change in a client’s advertising schedule, or a temporary lull in the economy can play havoc with an account executive’s expectations in a single month. Accordingly, much more serious attention is paid to the attainment of quarterly goals.

If business remains sluggish over an extended period, the general sales manager will contemplate steps to revive it. Rates may be lowered temporarily, for example. Additional sales incentives may be introduced. One station offered a ski trip to account executives who made calls on ten potential new clients in two weeks and completed at least one sale. All met the challenge and won a trip, and the station wrote $10,000 in brand new business. Of course, if these and other actions fail to produce the projected revenues, the only alternative will be a reduction in expenditures.

Qualities

To be effective, a GSM must possess many attributes. Chief among them are knowledge, administrative and professional skills, and certain personal qualities.

Knowledge

The general sales manager should have knowledge of

• Station ownership and management: The objectives and plans of the station’s owners and the general manager, and the role of the sales department in accomplishing them.

• The station and staff: The station’s strengths and weaknesses as an advertising medium, and the ways in which the sales function relates to the activities and functions of other departments; awareness of the motivations, potential, and limitations of sales department employees, and of their working relationship with staff in other departments.

• The market and the competition: Population makeup, employment patterns, cultural and recreational activities, and business climate and trends; the sales activities and plans of competing stations and media, their successes and failures.

• Sales management: The responsibilities of sales management and ways of discharging them. This includes familiarity with techniques, practices, and trends in broadcast sales and advertising; methods of estimating revenues and expenses, and of increasing revenues and controlling costs; methods, sources, and uses of marketing, sales, and audience research; marketing and sales techniques and practices, especially those used by retail stores and service companies; and the business, sales, and advertising objectives of clients and their past and present advertising practices.

• Content and audiences: Types of formats, programs, and other content, their demographic appeal, and audience listening or viewing habits.

Skills

Knowledge will be translated into success only if the general sales manager is able to combine it with both managerial and professional competence in

• planning the department’s objectives and strategies, explaining and justifying them to the general manager, and coordinating their accomplishment with staff and other departments

• organizing personnel and activities to attain stated objectives, and stimulating and directing employees toward their attainment

• managing the advertising inventory—that is, balancing the number of commercial units, availabilities, and cost-per-spot to maximize revenue

• controlling the department’s activities by careful attention to budget, personnel strengths and shortcomings, the achievements of competing stations and media, and research findings, and by taking appropriate actions

Personal Qualities

Selling often is referred to as a “people” business. For that reason, the GSM must be able to get along with people, both inside and outside the station. An outgoing personality, combined with a cooperative attitude and high ethical standards, are absolute necessities. But a friendly exterior will not spell success in the absence of other qualities.

General sales managers are charged with generating the bulk of the station’s revenues. Accordingly, they have to be

• ambitious in striving for the accomplishment of objectives

• competitive in approaching their responsibilities and meeting the challenges posed by other stations and media

• persuasive in their dealings with clients, advertising agencies, and the station rep

Finally, they must be adaptable to changing business conditions, and creative in developing sales techniques and promotions and in motivating their staff.

TIME SALES

Time is sold to advertisers by the second. The majority of sales in radio are 60-second spot announcements, called spots. In television, the 30-second spot is standard, and a limited number of 15- and 10-second spots are also available. Many broadcast stations also sell blocks of time for the airing of programs.

The Rate Card

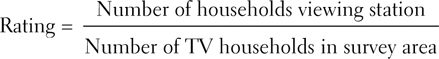

Traditionally, radio stations listed the cost of time on a published rate card. The major factors in determining cost were the time of day at which the spots were to run and the number of spots purchased, hence the name frequency card.

In time, most stations moved to a grid card in which the principal determinants are the supply of, and demand for, time. Grid cards are still used by many radio stations. Increasingly, however, computerization has permitted stations to introduce an electronic rate card. Using revenue goals and a variety of other variables, such as supply and demand, daypart, traditional sellout periods, and the flow of demand during the week, the station may select from a number of software programs to develop its rate structure.

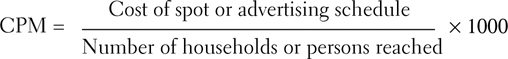

The electronic rate card in Figure 5.1 shows that the station sells time in four dayparts and that the cost of a 60-second spot varies by daypart and day of the week. Morning and afternoon drive times Monday through Friday are in greatest demand and command the highest prices. Costs increase as the week progresses. Although not included in the rate card, 30-second spots also may be purchased. In addition, the station offers a Total Audience Plan (TAP), whereby advertisers may obtain equal distribution of spots in the first three dayparts or in all four. The station also offers a discount when an advertiser buys an annual or long-term schedule. Stations are willing to give a price break in return for a guarantee of future revenue.

Figure 5.1 Radio station electronic rate card.

The electronic rate card offers several advantages. It compels the sales manager to pay continuing attention to inventory. As a result, inventory should be easier to manage and the station should be able to generate maximum revenues by pricing available time to reflect current supply and demand. At the same time, however, it reduces the account executive’s flexibility because special rates cannot be offered. Clients also may conclude that rates are negotiable because of their wide variation.

In addition to selling by daypart, most radio stations sell sponsorships in certain programs (e.g., news, sports) and in daily features (e.g., business report), with specific rates for each.

For the most part, television stations sell time in, and adjacent to, programs and not by daypart. They have used grid cards for many years to adjust rates in response to demand.

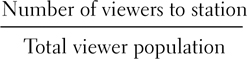

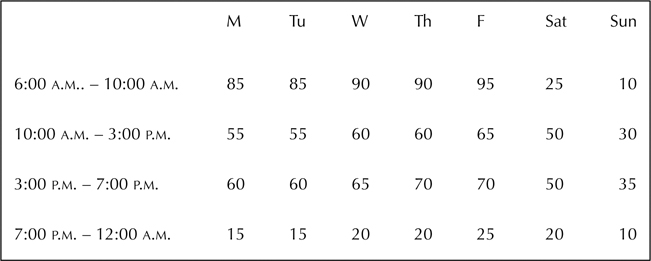

Figure 5.2 shows part of a grid rate card used by a television station that sells at five levels. As an example of how the selling level is determined, assume that demand for time in “Entertainment Tonight” is low. An advertiser may be able to buy 30-second spots at level 5, or $100 each. However, if demand is high, the advertiser may have to pay $450 at level 1.

Figure 5.2 Excerpt from television station grid rate card.

Note the following:

• Local news is in high demand and is priced accordingly.

• Prices of other programs rise and fall as audience size increases and decreases.

• The same rates are set for the one-hour game show block, the two-hour afternoon soap opera block, and the one-hour evening magazine block, without regard to the program in which the spot appears.

• Only the cost of 30-second spots is included on the card. However, other lengths are sold: 60-second spots at double the 30-second rate, and 15-and 10-second spots at 75 percent and 50 percent of the 30-second rate, respectively.

The station offers a discount to advertisers in its unsold inventory program. If time is not sold, the station is authorized to air participating advertisers’ spots up to a maximum monthly dollar amount.

The rate card in Figure 5.2 reflects costs in regularly scheduled, Monday through Friday programs on a network-affiliated station. Costs vary according to audience size for network prime-time programs. They vary, too, for weekend network sports programs, specials, and movies, and are influenced by the anticipated appeal of each to the station’s audience. Special rates are used for news updates, which usually include a 10-second spot and an open billboard announcing sponsorship.

Even though a rate card lists the costs of time, cash does not always change hands every time an advertiser obtains time on a broadcast station. Many stations exchange time for merchandise or services in a transaction known variously as a trade, tradeout, or barter. For example, advertisers may provide the station with travel, food, or furniture for its own use or as contest prizes, in return for advertising time with an equivalent cost. Some stations use trades to persuade hesitant businesses to advertise, and hope that they will be able to convert to a cash sale later. Merchandise or services instead of cash are accepted by many stations to settle delinquent accounts.

Barter programming also is used to acquire time. As noted in Chapter 4, “Broadcast Programming,” it permits a syndicator to obtain time, at no cost, for sale to national advertisers in return for supplying programs to the station without charge.

Cooperative, or co-op, advertising was mentioned earlier in this chapter. It allows a retailer to enjoy the benefits of advertising at less than rate card prices. In a co-op deal, the retailer receives from the manufacturer reimbursement for part or all of the cost of advertising that features the manufacturer’s product. The percentage of reimbursement usually is tied to the value of the retailer’s product purchase and carries a dollar limit. For instance, a hardware store may buy $20,000 worth of lawnmowers and qualify for 50 percent reimbursement to a maximum of $2,000.

Vendor support programs enable a retailer to obtain manufacturer (vendor) dollars to cover the advertising costs. In a direct vendor program, the retailer develops a proposal (often in cooperation with a station account executive) to promote the sale of a product, and presents it to the vendor or product distributor for financial support. For example, a grocery store may plan to highlight a product in an in-store promotion. It may propose a schedule of radio commercials that would advertise both the product and the store. In a reverse vendor program, the vendor approaches the retailer with funding to support a promotion. Monies provided under a vendor program are not subject to the kinds of product purchase requirements that apply to co-op, and represent another method whereby a retailer may acquire time without paying rate card prices.

Another method is through per-inquiry advertising, whereby an advertiser pays on the basis of the number of responses generated by the advertising. The practice is not widespread, but it is used by some stations, especially with mail-order companies that pay the station a percentage of money received on sales of the advertised product.

Per-inquiry advertising is frowned on by most stations. So, too, is rate cutting, often called “selling below the card” or “selling off the card.” Most stations express verbal opposition to cutting rates but many engage in it, especially when business is bad or when an advertiser threatens to make the buy on a competing station unless the rate is reduced.

Some stations disguise rate cutting by awarding advertisers bonus spots, also called spins. No charge is made for them since they are given as a consideration for buying other spots. The effect is that the advertiser receives time for less than the price quoted on the rate card.

Even though rate cutting may lead to a short-term spurt in sales for the station, it can result in a price war and create instability in the market. It conditions advertisers to believe that prices are negotiable and brings into question the value of commercial time on all stations. Ultimately, of course, it may be self-defeating, since stations have a limited amount of time to sell, and an increase in sales at less than the rate card price may not produce an increase in revenues.

Sales Policies

Time is a perishable commodity. Once it has passed, it cannot be sold to an advertiser. This fact imposes on the sales department an obligation to manage its commercial inventory in such a way that it produces the maximum possible financial return.

As a first step, the department must ensure that the rate card is realistic, based on considerations such as the size or characteristics of the audience, market size, and competitive conditions. But inventory management also requires the development of sales policies that will make time available and attractive to advertisers, and that will not result in audience tune-out.

Most stations have policies on the following:

As noted earlier, radio stations sell mostly commercial units of 60 seconds. Thirty-second units are the norm in television. Longer periods of time usually may be bought in both media for the broadcast of entire programs.

Most stations limit the number of breaks (called stop sets in radio) for commercials and other nonprogram material to reduce the possibility of alienating the audience with frequent interruptions in programming.

Stations that have only a few breaks per hour may have to air several minutes of commercials in each to meet revenue needs. Infrequent breaks may please the audience but upset the advertiser, whose commercial may become lost in a succession of announcements, a situation known as clutter.

Again, the goal is to schedule enough commercials to satisfy revenue demands, but not so many as to drive away audiences, especially to competing stations. Many stations continue to adhere to the standards of the now-discontinued radio and television codes of the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB). Under the Radio Code, stations agreed not to broadcast more than 18 minutes of commercials per hour. The Television Code limited network-affiliated stations to not more than 9 minutes and 30 seconds of commercials and other nonprogram material (e.g., promotional announcements) in prime time, and 16 minutes at other times. For independent stations, the limits were 14 and 16 minutes, respectively.

Most stations guarantee advertisers that the price in effect at the time a sales contract is signed will not change for a specific length of time, even if rates are increased in the meantime.

Advertisers prefer that commercials for competing products or services not be aired adjacent to, or in the same breaks, as theirs. A product protection policy guarantees that a certain time will elapse before such spots are broadcast. In practice, this has become a difficult policy for successful stations to implement. The demand for categories such as automotive, furniture, and fast food often exceeds the TV station’s available spot inventory, especially in news and prime-time programs. As a result, many stations no longer guarantee protection. Radio stations often establish protection priorities: (1) one-hour separation, if possible; (2) top and bottom of the hour separation; (3) stop set separation; (4) first and last spot in a stop set. Stations that do guarantee protection may allow advertisers a choice of a rebate, credit, or make-good if spots for competitors run back-to-back for some reason.

A policy that states the categories of products or services for which the station will not accept advertising.

The wording and/or visuals of commercials must meet standards determined by the station.

When a spot does not run or is aired improperly, the station offers the advertiser a make-good, or another time for the commercial.

A policy on costs the advertiser will incur beyond the purchase of time. Many radio stations include production and talent costs in the rate card price. However, such costs may be added to the purchase price if the commercials are sent for broadcast on other stations.

With two exceptions, a station creates sales policies that are consistent with its revenue objectives and its perception of responsible operation. The first exception grows out of the Children’s Television Act of 1990, which directed the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to adopt rules limiting the amount of commercial matter that television stations may air during children’s programming. As a result, the commission approved a restriction on commercial time in programs directed toward viewers 12 and under to 10.5 minutes per hour on weekends and 12 minutes per hour on weekdays. At the same time, it reaffirmed its long-standing prohibition on “program-length commercials” (i.e., programs associated with a product and within which a commercial for the product is broadcast), and on “host selling,” or the use of program talent to advertise products.

The second exception applies to both radio and television stations and deals with the sale of time to candidates for public office. The following policies apply.

Access Section 312 of the Communications Act of 1934

As amended, Section 312 gives the FCC the right to revoke a broadcast station’s license “for willful or repeated failure to allow reasonable access to or to permit purchase of reasonable amounts of time for the use of a broadcasting station by a legally qualified candidate for Federal elective office on behalf of his candidacy.”

Federal candidates are the only ones to whom a station must grant access or sell time. However, if time is sold to a candidate for any elective office, Section 315(a) of the Communications Act applies:

If any licensee shall permit any person who is a legally qualified candidate for any public office to use a broadcasting station, he shall afford equal opportunities to all other such candidates for that office in the use of such broadcasting station: Provided, that such licensee shall have no power of censorship over the material broadcast under the provision of this section.

Charges Section 73.1942(a) of the FCC’s Rules and Regulations

This section stipulates the prices that the station may charge political candidates:

The charges, if any, made for the use of any broadcasting station by any person who is a legally qualified candidate for any public office in connection with his or her campaign for nomination for election, or election, to such office shall not exceed: (1) During the 45 days preceding the date of a primary or primary runoff election and during the 60 days preceding the date of a general or special election in which such person is a candidate, the lowest unit charge of the station for the same class and amount of time for the same period. (i) A candidate shall be charged no more per unit than the station charges its most favored commercial advertisers for the same classes and amounts of time for the same periods. Any station practices offered to commercial advertisers that enhance the value of advertising spots must be disclosed and made available to candidates on equal terms. Such practices include but are not limited to any discount privileges that affect the value of advertising, such as bonus spots, time-sensitive make goods, preemption priorities, or any other factors that enhance the value of the announcement.… (2) At any time other than the respective periods set forth in paragraph (a) (1) of this section, stations may charge legally qualified candidates for public office no more than the charges made for comparable use of the station by commercial advertisers. The rates, if any, charged all such candidates for the same office shall be uniform and shall not be rebated by any means, direct or indirect. A candidate shall be charged no more than the rate the station would charge for comparable commercial advertising. All discount privileges otherwise offered by a station to commercial advertisers must be disclosed and made available upon equal terms to all candidates for public office.

Discrimination Section 73.1941(e)

This section provides that

In making time available to candidates for public office, no licensee shall make any discrimination between candidates in practices, regulations, facilities, or services for or in connection with the service rendered pursuant to this part, or make or give any preference to any candidate for public office or subject any such candidate to any prejudice or disadvantage; nor shall any licensee make any contract or other agreement which shall have the effect of permitting any legally qualified candidate for any public office to broadcast to the exclusion of other legally qualified candidates for the same public office.

Records Section 73.1943

This section requires stations to maintain and make available for public inspection certain political records:

(a) Every licensee shall keep and permit public inspection of a complete and orderly record (political file) of all requests for broadcast time made by or on behalf of a candidate for public office, together with an appropriate notation showing the disposition made by the licensee of such requests, and the charges made, if any, if the request is granted. The “disposition” includes the schedule of time purchased, when spots actually aired, the rates charged, and the classes of time purchased. (b) When free time is provided for use by or on behalf of candidates, a record of the free time provided shall be placed in the political file. All records required by this paragraph shall be placed in the political file as soon as possible and shall be retained for a period of two years. As soon as possible means immediately absent unusual circumstances.

Time Requests

The candidate is responsible for requesting equal opportunities:

A request for equal opportunities must be submitted to the licensee within 1 week of the day on which the first prior use giving rise to the right of equal opportunities occurred: Provided, however, That where the person was not a candidate at the time of such first prior use, he or she shall submit his or her request within 1 week of the first subsequent use after he or she has become a legally qualified candidate for the office in question.1

Proof

Additionally, proving that the equal opportunities provision applies rests with the candidate:

A candidate requesting equal opportunities of the licensee or complaining of noncompliance to the Commission shall have the burden of proving that he or she and his or her opponent are legally qualified candidates for the same public office.2

Local And Regional Sales: the Account Executive

As indicated earlier, local and regional sales are the responsibility of staff members known as account executives.

Hiring

Success in attaining sales objectives is tied closely to the station’s ability to attract and select persons with the appropriate background and personal attributes. If they are selected wisely, the station will reap significant financial returns; if not, the station will face constant turnover, resulting in lost sales, disruptions in relationships with clients, and the time, effort, and expense of finding and training replacements.

Sources

Many people are attracted to careers in broadcasting because of the glamour that accompanies work as a disc jockey or television news anchor, or the opportunity for creative expression through writing or production. Relatively few show an initial interest in sales, despite the fact that it offers better financial prospects and an avenue for advancement to top management.

In their search for account executives, stations turn to various sources:

• Other stations: Persons working as account executives in other stations in the market bring with them familiarity with broadcast sales, local clients, and the community. Those hired from outside the market are familiar with the first, but have to develop relationships with clients and an awareness of the community.

• Other media: Newspapers, outdoor, transit, and other advertising media provide a source of employees with knowledge of sales and advertising and an understanding of the methods, strengths, and shortcomings of the medium in which they have been employed.

• Advertising agencies: Awareness of agency practices, clients, and the relative advantages and disadvantages of different media are among the qualities offered by advertising agency account executives and media buyers.

• College or university graduates: Broadcasting or communication graduates bring to the position some knowledge of media theory and practices. Business graduates may be equipped similarly in sales and marketing. The best prospects are those who have included in their academic program an internship, or who have gained practical experience through part-time work.

• Other: Other sources include persons currently working in the station, especially in sales, traffic, continuity or creative services, or production. They are familiar with the station and its personnel, and should understand the role and responsibilities of the account executive. Persons with a successful background in selling, especially in the sale of intangibles, also may have the experience and potential to succeed.

Qualifications

Probably the best predictor of success as an account executive is a record of accomplishment in broadcast sales. However, in selecting among all candidates, the station should consider knowledge, skills, and personal qualities.

Knowledge

Applicants for account executive positions should have, or show the ability to develop, knowledge of

• Broadcast and other media: their operations, personnel, and relative strengths and weaknesses as advertising vehicles.

• The station and its competitors: programming, personalities, coverage, and the characteristics of audiences for different formats or programs.

• The market: employment, work hours, households, retail sales, consumer spendable income, buying habits, and the listening or viewing population.

• Sales and marketing: techniques and practices, and the categories, sales cycles, and special sales periods of retailers.

• Research: terminology, and the uses of research in sales.

Skills

The account executive should have the ability or potential to set and attain objectives, plan and manage time, communicate effectively, keep accurate records, and relate to people and their problems. On a daily basis, skills in preparing and delivering sales presentations, selling and servicing accounts, and interpreting and using research are required.

Personal Qualities

Ambition, initiative, and energy are prerequisites for anyone seeking success in sales. Persistence, persuasiveness, imagination, integrity, and professionalism in behavior and dress are equally necessary for the broadcast account executive.

Training

Stations recognize that new employees with little or no experience will be productive only if they understand what is expected of them and are equipped with the knowledge and skills to function effectively. To accomplish those goals, the Television Bureau of Advertising (TVB) partners with The Center for Online Learning in a self-administered and self-paced sales training course over the Internet. The Radio Advertising Bureau (RAB) provides a variety of training opportunities for radio sales personnel. Many stations prefer to organize customized training programs to introduce new account executives to their responsibilities and to the information and techniques they will be required to master to achieve success in the market.

Typically, a program includes details of the station’s expectations on the number of contacts and sales presentations, and the amount of business that should be accomplished within a certain period of time. It introduces the employee to the medium, and to the station and its personnel, particularly those departments and people whose work affects, or is affected by, the sales department.

For example, the new account executive should become familiar as soon as possible with the station’s format or programming, and with traffic, continuity or creative services, and production personnel and practices. Methods of prospecting or finding new business, preparing and presenting sales proposals, processing orders, maintaining records, and compiling activity reports should also be covered.

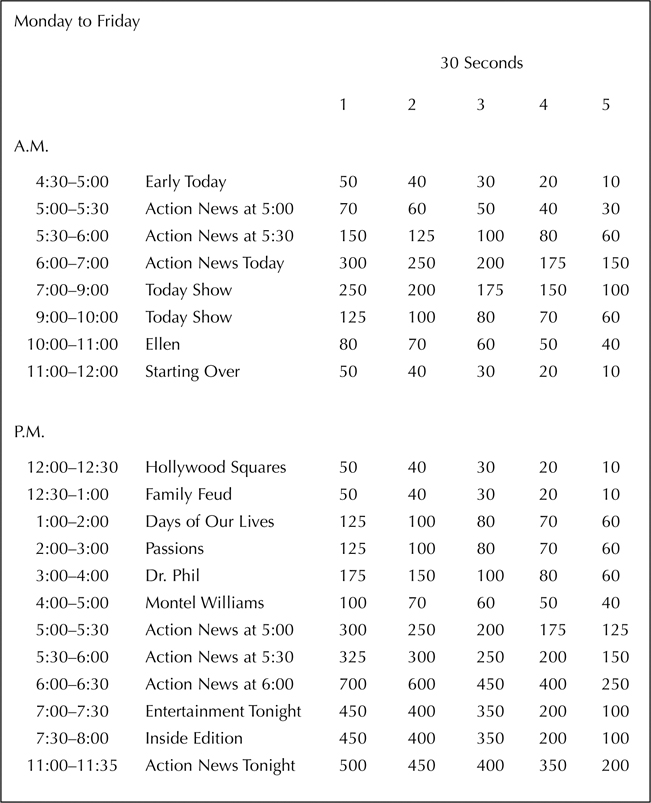

Figure 5.3 contains an example of a two-week training program for radio station account executives. In addition to the activities listed, trainees are required to complete daily readings, listen to audio tapes, view videotapes and slide-tape presentations, and spend part of each day observing the work of the sales department.

Figure 5.3 Training program for radio station account executives.

New employees with previous broadcast sales experience may not be required to participate in all training activities. However, they should attend those that permit them to become familiar with the station and its personnel and with the department’s sales policies and practices.

Training does not end with an initial program of the kind outlined in Figure 5.3. It should be a continuing requirement for new and existing account executives so that they may enhance their knowledge, stay abreast of new sales techniques and strategies, and seek additional means of revenue enhancement.

One method employed by many stations is the generation of revenue beyond the sale of airtime. It is termed non-traditional revenue (NTR). RAB reported in 2004 that more than 60 percent of station survey respondents said they include the topic in their training. Topping the list of NTR activities in which stations engaged were event marketing, cause-related marketing, and the Internet.3 One station organizes a sports and leisure show in a mall and derives revenue from the sale of booth space to event exhibitors. A station might identify financial support of the public schools as its cause and promote the sale of books containing discount coupons for use at restaurants, stores, and entertainment and cultural venues. To generate revenue, the station might sell mentions of participating companies in its on-air promotions. The sale of classified advertising on the station’s Web site is an example of a way in which an increasing number of stations are using the Internet as a source of non-traditional revenue.

Sales Tools

The most important tool of the account executive is knowledge that will permit the creation of a sales proposal geared to the interests and needs of each client or prospect. Knowledge of the market, the station, and the client are of particular importance.

Market Data

The account executive should be familiar with the people and business activity of the market, including the size and composition of the population, median income and purchasing power, and retail sales and buying patterns. Knowledge of the workforce and working hours, and of cultural and recreational pursuits, also should be part of the account executive’s database.

Station Data

To show how the station can assist the client or prospect in attaining objectives, the account executive should have knowledge of the station’s

• audience, especially those characteristics that are important to the advertiser and how they compare to the characteristics of audiences for competing stations or programs

• format or programs, and their appeal to the advertiser’s actual or potential customers

• commercial policies, particularly those that will afford the advertiser distinctive, uncluttered access to the audience

• availabilities, to show how the prospect can gain access to targeted customers

• rate card, to present a package that meets the advertiser’s objectives at an acceptable cost

Other data that may be helpful in making a sale include the success achieved by advertisers currently using the station, awards won by the station and its employees, and the quality of staff and the facilities available to produce commercial messages.

Client Data

One of the most frequent objections by advertisers is that account executives do not know the advertiser’s business. Some stations try to alleviate that problem by inviting current advertisers to station sales meetings to educate the sales staff. However, in compiling a tailor-made proposal, the account executive must understand the particular needs of each client or prospect.

To do that effectively calls for detailed knowledge of the company, its products or services, its customers, and its competitors. Familiarity with the company’s objectives, current advertising practices, and advertising budget also is required.

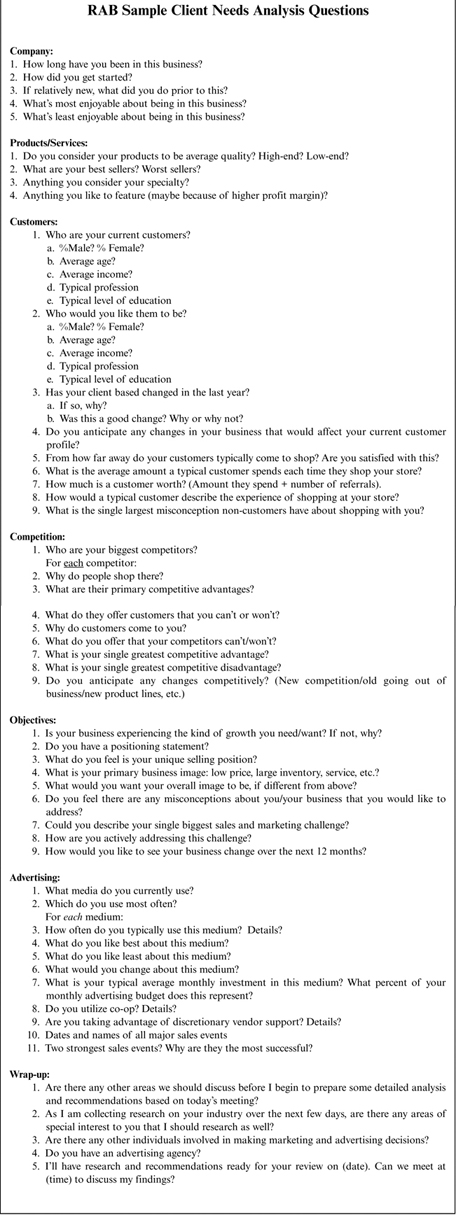

The process whereby an account executive obtains such information is known as a client needs analysis. RAB has developed a series of questions to complete the analysis and they are reproduced in Figure 5.4. Answers to the questions should permit the account executive to develop a profile of the business and to prepare a sales proposal that will be responsive to the prospect’s needs.

Figure 5.4 RAB sample client needs analysis questions. (© Radio Advertising Bureau. Used with permission.)

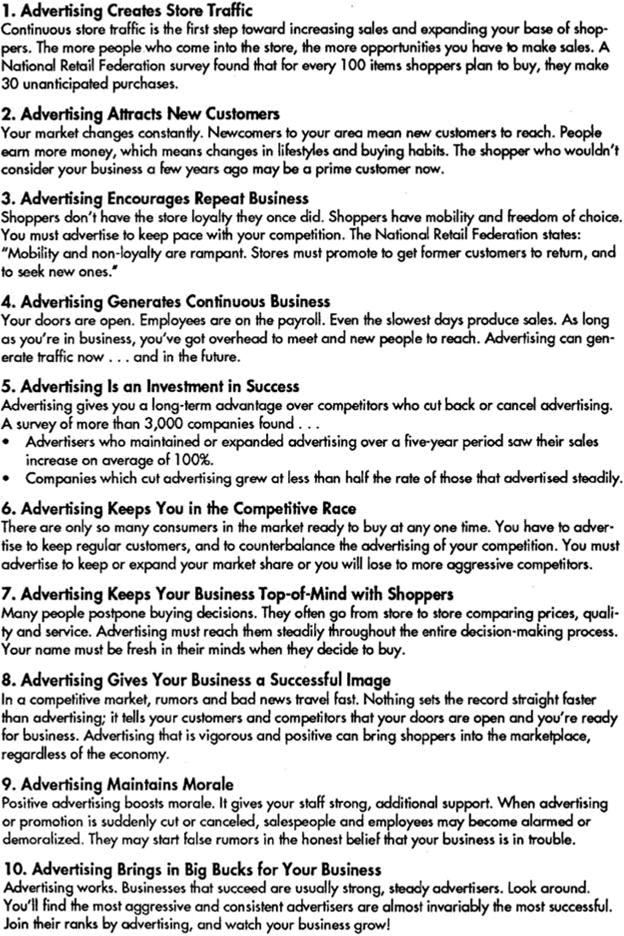

Knowledge of the market, station, and prospective client may not be sufficient for prospects who have not engaged in paid advertising in the past. They may have to be convinced of the value of advertising and, for that reason, the account executive should be familiar with the benefits that advertising brings. RAB’s list of ten reasons to advertise (Figure 5.5) provides useful information to meet such a challenge.

Figure 5.5 RAB’s ten reasons to advertise. (© Radio Advertising Bureau. Used with permission.)

Prospects who have not used radio or television previously may have to be persuaded of the medium’s advantages as an advertising vehicle. The radio account executive may cite some of that medium’s strengths:

• it reaches virtually every U.S. consumer

• it accompanies customers and prospective customers wherever they go and whatever they are doing

• it offers desired targetability through a wide range of format and programming options

• it reaches the big spenders

• it allows advertisers to achieve the message frequency necessary to stand out from the competition

• it is the only truly portable, mobile medium

• it reaches customers and prospective customers right up to the time of purchase

• it mixes well with other media, and takes up where those media fall short

The television account executive may point to that medium’s

• persuasiveness, growing out of its combination of sight, sound, motion, and color

• reputation as the most memorable, credible, exciting, and influential advertising medium

• capacity to involve viewers emotionally

• ability to demonstrate products and plant in viewers’ minds images of product packaging, uses, and benefits

• broad demographic appeal and ability to reach all demographics · large daily audiences

• wide geographic coverage

• record of bestowing prestige on advertisers and products

Many stations include relevant market and station data in a sales kit, a variety of materials usually contained in an attractive folder and designed to demonstrate the station’s ability to generate traffic for the prospect. The kit might consist of details of the market’s population, the size and characteristics of the audience, personality profiles, a coverage map, cost and effectiveness comparisons with other media, and reprints of newspaper or magazine articles about the station and of the station’s trade and consumer advertising.

The Sales Proposal

In the past, account executives relied heavily on the sales kit to obtain an order. They expected that an impressive array of information about the station would be sufficiently persuasive. What they failed to realize is that advertisers are interested in the station only when they understand how it can help further their business.

Today, sales managers demand written, custom sales proposals. Instead of an all-purpose collection of materials, account executives are required to develop a personalized proposal that addresses the special needs of each potential client. The proposal includes frequent references to the prospect, and the material is organized for easy understanding. It is brief and to the point.

For example, a radio station’s proposal to an above-ground pool retailer that does not advertise on radio might begin with a list of campaign objectives: for example, position the store as the best in the market and pool ownership as simple, economical, and fun; and identify the targets as families with children, living in outlying areas. That might be followed by a description of campaign strategy: a heavy schedule of commercials to make the message inescapable; a repetition of the themes of speed and ease of installation, simplicity of maintenance, and low monthly payments. A statement about radio’s ability to reach families throughout the day and to do so at a lower cost than competing media might be followed by details of the target audience (adults aged 25 to 54) that listen to the station in outlying and rural areas where above-ground pools are very popular. Finally, the campaign objectives are repeated and a specific advertising schedule is presented, showing the number of spots proposed, when they would air, and the weekly cost.

Note that the proposal includes a recommended advertising schedule. Merely to sell time would bring the account executive a commission, but might not produce increased business for the advertiser and could make it difficult or impossible to obtain a subsequent order.

The most widely accepted measures of a schedule’s effectiveness are reach and frequency. Reach refers to the number of different homes or persons targeted by the advertiser who see or hear the commercial. Frequency is the number of times the targeted homes or persons are exposed to it.

Both goals may be accomplished through a saturation schedule, a heavy load of commercials aired in time periods when the targeted homes or persons are tuned in. In contrast, a spectrum plan exposes different people to the commercial, but only occasionally. It involves the purchase of a moderate number of spots distributed throughout the day.

A spot schedule is a series of commercials aired in only one or two periods of the day, and is aimed at reaching the target audience that is most available during those periods. It is used to reach a large number of people in a particular demographic category.

A rotation plan gives an advertiser exposure to a similar or different audience over a period of time. With horizontal rotation, the commercials are broadcast at or about the same time daily. Vertical rotation places the commercials throughout the day.

Advertisers who want to stretch their campaign may buy time on an “onand-off” basis. In other words, they may run a succession of two-week schedules with a one-week interruption between them. Some account executives refer to this practice as a blinking schedule.

The Sales Call

Account executives handle two kinds of accounts:

• Direct: The account executive deals directly with the advertiser, obtaining the order and receiving the copy and/or spot or arranging for the commercial to be written and/or produced by the station. The station bills the advertiser.

• Agency: An advertising agency writes and/or produces (or arranges for the production of) the client’s commercial and buys time from the account executive on the client’s behalf. The station bills the agency, which receives a commission of 15 percent on the dollar amount of time purchased.

Many new account executives have to prove they can develop new business and have a clear understanding of the sales process and client service before they are assigned to an active account. Once they have provided proof, they join other account executives in working on an exclusive list of accounts.

The most equitable method of compiling the list is to assign a variety of product or service categories to each salesperson. Assigning on a geographical basis so that all areas of the market are covered can lead to imbalances in sales opportunities and create morale problems. Assigning by category (e.g., furniture stores, automobile dealerships) enables the account executive to develop a good knowledge of the product and of category sales and marketing practices, but many advertisers object to dealing with someone who does business with competing companies.

In addition to equity, a major consideration in assigning accounts is compatibility. Usually, attempts are made to match an account executive with a prospect or client on the basis of their respective personalities and temperaments.

The purpose of sales calls is to obtain an order. However, few sales are made the first time an account executive calls on a prospect. Often, the first meeting is used to learn as much as possible about the prospect’s business and needs so that a proposal may be prepared for presentation during a second visit.

To successfully generate initial and repeat sales to a direct account, the account executive should take certain actions before, during, and after the call:

Before

Identify the person who handles the prospect’s advertising and is authorized to buy time and sign a sales contract.

Make an appointment to meet with individuals at their convenience. Develop knowledge of the prospect’s

• business or service

• customer characteristics

• past and present advertising activity

• advertising budget (or an approximation) and how and when it is allocated

• objectives and problems

• previous dealings with the station, if any

Be aware of the interests and personalities of the persons to whom the proposal will be presented, and of their buying habits (e.g., whether they buy in small or large quantities).

Prepare a proposal that addresses the prospect’s needs and includes an advertising schedule and its costs.

Ensure that printed or other materials for the presentation are ready and taken on the call. Increasingly, account executives are turning to PowerPoint to present the proposal. It offers the opportunity for greater effect than the printed page through the inclusion of colorful graphics, audio, and still and moving pictures. If it is to be used, make sure that it is complete and free of errors.

During

Describe and explain the proposal, with frequent reference to the prospect’s needs and the ways in which the proposal will help meet them. Remember to

• keep the presentation brief

• invite questions, and design the answers so that they reinforce major points contained in the proposal

• ask for the order

• have the client sign and date the sales contract

• obtain a production order if the client wants the station to write and/or produce the commercial

After

Process the order. The routing of the order varies, but generally it is checked by the local sales manager and then cleared against availabilities. If requested times are available, details are sent to traffic for entry on the program log. If copy and/or production are required, relevant information is provided to the persons responsible. In some stations, bookkeeping receives a copy of the order for billing purposes; in others, clients are billed from the log.

Prepare a report on the call, noting the name of the client and the person seen, the date, the content of the presentation, its results, and comments.

Service the account. Diligent servicing paves the way for subsequent sales. It begins with monitoring the progress of the order from its delivery at the station to the time the commercial begins to air.

Problems can occur, and it is the responsibility of the account executive to ensure that they are resolved. Additionally, the account executive should check with the client regularly during the advertising’s schedule to assess its results. Adjustments may be necessary if the commercial appears to be having limited or no effect. Maintaining contact with the client is a continuing responsibility, and should be accompanied by acts of appreciation, such as invitations to lunch or dinner, offers of tickets to cultural, sports, and other events, or similar gestures.

If a sale did not result from the call, the account executive should analyze the reasons why and develop another proposal that addresses the prospect’s reservations or concerns. Sometimes, the failure may be explained by the account executive’s inability to position the station in such a way that a buy makes sense. Often, it may result from the way in which objections raised by the prospect are handled. Most are predictable, and the account executive should anticipate them and be ready to respond.

The following are among the objections mentioned most frequently, and the actions that may be taken to counter them:

Probe to discover what the prospect is using for comparison. Another station? Another medium? Point to the prospect’s selection of a superior (and more expensive) location for doing business or to something about the business (e.g., a large and impressive sign) that is expensive but, presumably, successful. Stress that the prospect will be buying much more than a schedule of commercials, such as the number of people who will be reached, their characteristics (underlining the fact that they are potential customers), the station’s expertise in commercial production, and so on. Rather than speaking of the cost of the schedule, emphasize the cost of reaching individuals and how it compares to other stations or media. Use the experience of other advertisers on your station to show that you can help the prospect increase business and profits.

If you don’t know the prospect’s current advertising budget and its disposition, try to find out. Use that information, or your estimate, to demonstrate the affordability of your station and its ability to reach more potential customers. If appropriate, raise the possibility of co-op or vendor support programs to exemplify how the prospect can enjoy the benefits of additional advertising at little or no added cost, and detail the assistance the station will give in carrying out such programs.

Ask for more information. You will probably learn that the prospect bought a short and inexpensive schedule on a radio station or in a TV daypart with the wrong demographics, or that the commercial was poorly written or produced. Point out those likely causes of disappointment and explain how you will do things differently. Again, use facts and examples to illustrate the effectiveness of radio or television advertising and the ability of your station to reach the prospect’s customers.

Refer to data on who buys what and show how many of them are reached by your station. This response also can be used to meet a price objection if the prospect is advertising on a radio station that does not attract large numbers of the prospect’s potential customers, or in TV dayparts or programs that skew to less-than-desirable demographics.

Tell the prospect what happened to John Smith. If he has been fired, so much the better. You can use that information to emphasize your station’s commitment to giving clients the best service. If he is still employed by the station, make the point that the station considers the prospect important enough to assign another account executive. Give an assurance that similar bad experiences will not occur in the future.

This objection reflects a fear of change. Find out when the prospect first advertised with WAAA. Speculate aloud about the concerns that accompanied that decision and reinforce the success that resulted from it. How will the prospect’s business grow from this point? Your station provides that opportunity by offering the means of reaching new or larger audiences of potential customers or by adding to the mix of customers. Again, it may be advantageous to compare your station’s cost and production quality with those of WAAA.

The account executive should listen closely to every objection and seek clarification or additional details. For example, a blanket statement like, “I tried radio and it doesn’t work” is not specific enough to understand what gave rise to it or to frame a satisfactory response. Further questioning may reveal that the prospect spent $250 on a schedule with a station whose listeners were not potential customers. Now, the objection has moved from radio in general to a specific radio station, and that is easier to handle. The account executive can use the new information to speak about radio’s ability to target particular demographics and to describe the represented station’s proven record of attracting listeners in the demographic group that buys the prospect’s products.

The account executive’s principal contact in agency accounts is with media buyers. Generally, they are much more knowledgeable than retailers about broadcast advertising, and their concerns are different. While a retailer is interested in results (i.e., generating more customers), a media buyer focuses on rating points and costs.

Assume that a decision has been made to buy a schedule on a television station. A request is made for a list of avails for the quarter. The buyer will identify the required demographic (e.g., men and women aged 25 to 54), restrictions (e.g., no time before 4:00 P.M. or after midnight), the amount budgeted (e.g., $25,000), and the cost-per-point sought (e.g., $20). The account executive uses an appropriate computer program to arrive at the most efficient schedule based on the buyer’s stipulations. Negotiations continue until agreement is reached on schedule and cost. If the schedule fails to deliver the promised ratings, the media buyer usually requests additional spots at no cost to make up for the difference.

Sales presentations to agencies are prepared in much the same way as those for retailers and must be scheduled to meet the buyer’s quarterly purchasing cycles. They pay special attention to client needs, but they also recognize the buyer’s interest in rating points and costs, and are designed to address it.

Compensation

As noted in Chapter 3, “Human Resource Management,” financial compensation for sales personnel differs from that of other staff. The seven principal methods are

• Salary only: Sales managers who do not service clients, co-op coordinators, and trainees are most likely to be compensated on a straight salary basis.

• Salary and bonus: Salary combined with a bonus based on net sales revenues; used mostly for sales managers. Some managers also receive an override, a percentage of total billings.

• Straight commission: The most common method for account executives. It permits the more successful to earn comparatively large salaries.

• Draw against commission: Account executives establish their own minimum compensation, or draw, and receive that amount as long as their sales commissions meet the goal during the specified period, usually a week or month. Commission is paid on all sales that exceed it. Some stations provide a guaranteed draw. In other words, the compensation is paid even if the sales goal is not met. However, the guarantee generally remains in force for a limited period.

• Salary and commission: Used for managers with a client list, account executives, and co-op coordinators.

• Salary, bonus, and commission: Managers who continue to service clients are most likely to fall into this category.

• Straight commission with bonus: Account executives and managers servicing clients may be compensated in this way.

The account executive must receive enough money to enjoy a reasonable standard of living and a sense of security during the initial period of employment. Some stations attempt to provide both by using straight salary for several months, moving to commission and a smaller salary, and, ultimately, to straight commission.

Commissions may be paid on billings or on billings collected. If billings are used, commissions are adjusted later if payment is not received from the advertiser. The billings collected method usually leads the account executive to check the credit rating of prospective clients before attempting a sale, and to take extra effort to ensure that bills are paid and delinquent accounts settled.

With the exception of salary only, all compensation methods use commissions and quotas to stimulate effort and productivity. Most stations employ additional incentives, with monetary or other prizes as inducements.

Individual or team sales contests are common in many stations, with points determined on the level of accomplishment. For example, new accounts may be worth 25 points, new business from clients who have used competing stations, 20, and increasing sales to current accounts, 15. Other accomplishments meriting points might include generation of the greatest dollar amount of new business or the greatest percentage increase in business.

Other incentives include extra commissions, such as paying a higher percentage commission on new than on repeat business or on production beyond quota. One radio station rewards account executives who reach their established revenue goal with a four-day weekend by giving them a day off on the Friday preceding a Monday national holiday.

Prizes should take into account the motivations of employees. A small monetary reward may not be very appealing to an account executive earning more than $100,000 a year. Similarly, a trip to a nearby resort may not be viewed as valuable by someone who does a lot of traveling.

Contests that are won regularly by the same few people may injure rather than assist the sales effort. For that reason, many stations prefer group incentives. A television station awards a collective bonus when quarterly budgeted sales revenues are exceeded. Everybody has a reason to lend their best efforts to the endeavor since all benefit if the goal is achieved.

One way of reaching for any sales goal is through additional sales to existing clients. Another is through the attraction of new clients, a responsibility of all account executives. It is particularly important for the new employee, who may have only a short client list, or no list at all.

Monitoring other media can provide useful leads in identifying new accounts. Thumbing through the local newspaper and tuning to other stations will reveal who is advertising, what they are advertising, and the targets and appeals being used. Analyzing the ads permits the account executive to develop a sales proposal for the advertiser, using the products, audiences, and appeals of the current campaign.

Many newspapers carry stories announcing the opening of new businesses. Government offices maintain records of business licenses granted and building permits issued. These and other sources provide valuable clues for the account executive in search of clients.

National Sales: The Station Rep

Most national advertising is bought by advertising agencies with offices in large cities such as New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Atlanta, and Dallas. Since it would be impossible for the majority of broadcast stations to maintain a sales staff in those cities where major agencies buy time, they engage a station representative company, or rep, to sell time on their behalf.

The rep is, in effect, an extension of the local sales force. Rep sales are billed by the station to the agency, which deducts its 15 percent commission. From the balance, the station pays the rep a commission, as set forth in the contract between the two. It may run from about 5 to 15 percent of the gross business ordered (i.e., the amount billed to the agency). One reason for the range in rates is the ability of multiple-station owners to negotiate a reduction based on the number of stations to be represented.

Selecting the Rep

National sales may account for as much as 50 percent of a station’s sales revenues. Selection of a rep, therefore, is an important decision. Among the considerations to be weighed before contracting for the services of a rep firm are these:

• Ownership and management: Who owns and who manages? Who provides direction and leadership, and how are they provided?

• Services: In addition to national sales, what services will the company provide? Will advice be available on programming, promotion, research, and local sales? What about assistance in collecting past-due accounts?

• Offices: Does the firm have enough offices, and are they located in appropriate cities to give effective national sales coverage?

• Staff: How many employees are assigned to sales and to other services in the company’s offices? What kind of educational and professional background do they have? How are they trained and compensated? Is the staff stable?

• Stations represented: Does the company specialize in representing particular kinds of stations or stations in particular kinds of markets? How many stations does the company represent, and how long has it represented them? Which stations? Do they include similar properties?

• Sales teams: How many sales teams does the rep have? How many stations are on each team? Are TV affiliates and independents mixed?

• Reputation: What is the company’s reputation with national advertising agencies and with stations already represented? How is it perceived by other station rep companies?

• Sales philosophy and practices: Are they compatible with those of the station?

• Cost: Is the commission realistic? How does it compare to that paid by similar stations in similar markets for the same services?

Rep Services

The basic service offered by a rep company is the sale of national spot advertising on stations it represents. Sales are accomplished through rep account executives, who make regular calls on media buyers in advertising agencies.

Much of the information used by the account executives is developed by rep employees engaged in research on, among other items, programming, products, advertisers, and broadcast markets and audiences. Their work enables the rep company to offer a second service: consulting on a range of station activities, all of which have an impact on the sales effort.

Most rep firms offer advice to stations on the following:

• Sales and sales strategy: Sales includes rate card development, sales training, and presentation materials; sales strategy includes the basic posture of the station as it enters a given quarter and changes in that posture as time passes.

• Budget development: The rep’s projections of market and station billings for a future year.

• Programming: Local programming and the purchase of syndicated programs and features.

• Research: Research methods, interpretation of research, application of findings; information and analysis on business considerations (e.g., switching network affiliation, expanding local news, financial impact of airing a syndicated program instead of clearing the network lineup).

• Promotion: Audience and sales promotion methods, preparation of trade and consumer advertisements, public relations.

To represent the station effectively and to maximize the advertising dollars flowing to the station, the rep must be supplied with data on the station, competition, and market. Information on the station would include

• availabilities and rate card

• audience coverage, ratings, and other research reports (e.g., local marketing research)

• format or program schedule, features, specials, and sporting events

• news releases on the station, its personnel, and achievements and awards

• promotions, and examples of trade and consumer advertising

• local, regional, and national clients, and advertising effectiveness as documented in communications from advertisers and agencies

The rep also would find it helpful to receive details of station facilities, especially those that distinguish it from the competition, the station’s role and image in the community, and, for radio, an air check and personality profiles.

To the degree possible, the station should provide the rep with similar information on competing stations in the market, drawing particular attention to those characteristics that suggest, or demonstrate, the represented station’s superiority.

The rep may have to sell agencies on the worth of the market as well as the station. Accordingly, the station should supply details of the community’s media and their circulation, population makeup and trends, employment categories, major employers, and pay days. Details of the market’s educational institutions and cultural and recreational activities also would give the rep a profile of the market.

Station-Rep Relations

The principal contact between the station and the rep company is the person responsible for national sales, usually the general sales manager or the national sales manager. If the relationship is to be productive, it must be characterized by trust and confidence.

To establish and maintain such an atmosphere requires open and constant communication. The station must satisfy the rep’s information needs promptly and accurately. In particular, the rep must be aware of all availabilities and of modifications in the rate card, and must be provided with details and explanations if spots are not aired as ordered. The rep must also be advised of changes in the programming of the station and of competing stations. The station should be informed of the status of ongoing negotiations with agency buyers, and has a right to an explanation if potential sales are not closed by the rep.

Communication can be enhanced through regular visits to the rep’s offices by the station’s general manager as well as the general and national sales managers. Such visits provide opportunities to sell the market and the station and to exchange ideas and information. Similarly, appropriate members of the rep’s management team should visit the station periodically.

The station should reply promptly to rep requests for availabilities, and clear and confirm sales orders as quickly as possible. Timely payment of commissions also contributes to good relations.

Since the rep company is a partner in the sales effort, it should be involved in the development of sales objectives and plans, and in the review of their progress. And the rep should be recognized for significant accomplishments through congratulatory letters and awards.

RESEARCH AND SALES

The sales department relies heavily on market and audience measurement research. For the most part, market research is qualitative. It includes, for example, information on new businesses and on demographic and employment changes, much of which the department may obtain from the chamber of commerce, business news announcements and stories in local newspapers, and census reports. More comprehensive data on factors such as the occupation, education, income, and buying habits of station audiences and the population in general may be purchased from market research companies.

Typically, audience research is quantitative and consists of a count of listeners or viewers categorized by age and gender. It is usually bought from independent companies. Account executives use it to provide clients with details of audiences that will be reached through a commercial schedule and to demonstrate the schedule’s efficiency. It is also a useful tool for reviewing the rate card.

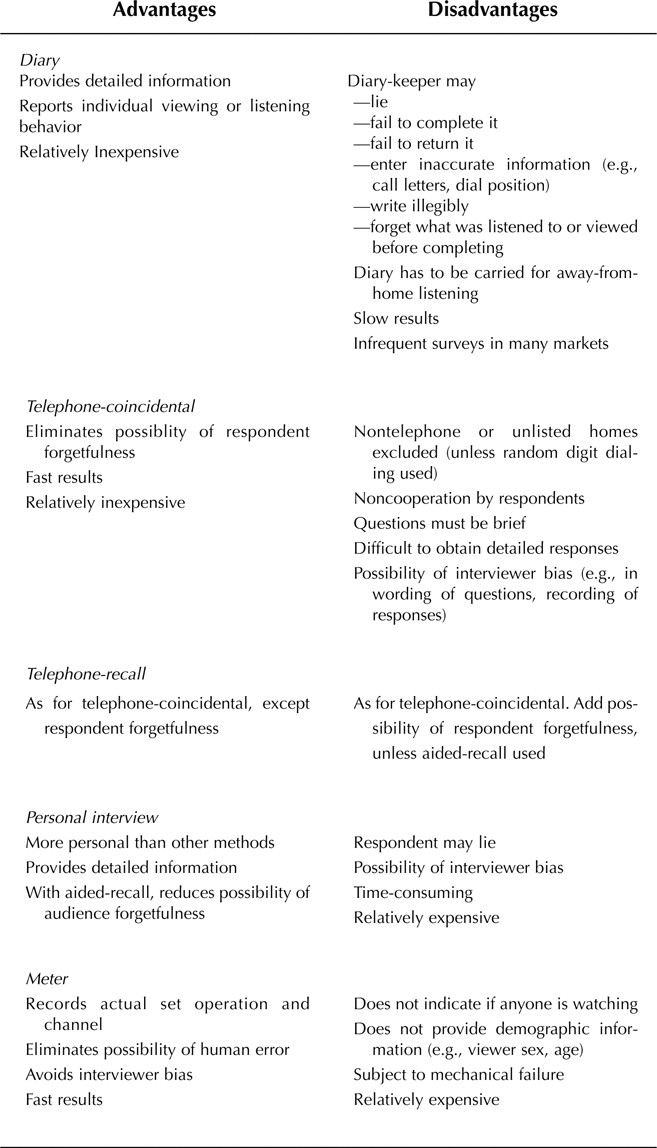

Three principal methods are used to estimate audiences for radio and television stations. A fourth is used only for television. Each employs a process known as random sampling, which means that each household or person in the population being surveyed has an equal chance of being selected. Accordingly, the viewing or listening behavior of persons or households in the sample group can be projected to that population. The measurements are estimates, and are subject to a sampling error. In other words, the actual audience may be a little larger or smaller than reported. The survey methods are as follows:

• Diary: Daily viewing or listening activity is recorded in a small booklet or log for one week.

• Telephone: Interviewers ask what station or program is being listened to or watched at the time of the call. This is known as the telephone-coincidental method. In the telephone-recall method, participants are asked which stations or programs were listened to or viewed during an earlier period of time (e.g., the previous day or evening).

• Personal interview: Interviewers visit people in their homes and question them about their listening or viewing.

• Meter: A monitoring device records the channel to which the television set is tuned and is connected by telephone to a central computer.

Each method has advantages and disadvantages, and some of them are listed in Figure 5.6.

Figure 5.6 Advantages and disadvantages of broadcast audience measurement methods.

The sales department, station rep, and advertising agencies use audience estimates compiled chiefly by Nielsen Media Research (television) and The Arbitron Company (radio).

Nielsen surveys all 210 television markets for four-week periods in November, February, May, and July. Some of the larger markets are surveyed seven times a year, through the addition of October, January, and March. These simultaneous surveys are known as “sweeps.”

Arbitron conducts continuous measurements in most of the top-100 radio markets and a handful of lower-ranked markets for 48 weeks a year, in four, 12-week cycles. Other markets are measured for 12 weeks twice a year (spring and fall).

In more than 50 large markets, Nielsen uses a household meter to collect TV set usage data (i.e., set on/off, channel tuned) in the preparation of overnight reports. In the top ten markets, it is introducing a different kind of meter, the local people meter (LPM). However, the basic measurement method for television stations in all markets is a diary, which sample households complete for each television set for one week. Each day is broken down into 15-minute periods. Respondents are asked to note the station or channel name, the channel number, and the name of the program or movie to which the set was tuned in each period, together with the age and gender of all family members and visitors viewing and the number of hours each person works per week. VCR recording activity also must be included.

For radio, Arbitron supplies a one-week diary to each member of selected households 12 years of age and older. Respondents enter in the diary (1) the start and stop times of each listening period; (2) station identifiers (e.g., call letters, dial setting, station name, or program name); (3) whether the station was AM or FM; and (4) whether they heard it at home, in a car, at work, or in some other place.

At the end of the week, the completed television or radio diaries are mailed to the respective companies. The information they contain is processed and some of the results published in a local market report, more commonly called a ratings book or, simply, the book. In metered television markets, the set tuning information is augmented at least four months a year with demographic viewing data from a separate sample of diary households.

The television report estimates, by age and gender and for different time periods and programs, the audience for stations in the market. The radio report lists audience trends and current estimates by age and gender for different time periods. It also contains details of listening locations, time spent listening, and the ethnic composition of station audiences.

Market report information prepared by Nielsen and Arbitron is organized according to the geographic area in which viewing or listening took place. The following areas are used in the Nielsen Station Index (NSI) report:

• Metro area, which generally corresponds to the metropolitan statistical area (MSA), as defined by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget.

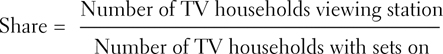

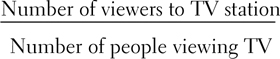

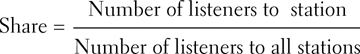

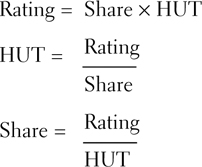

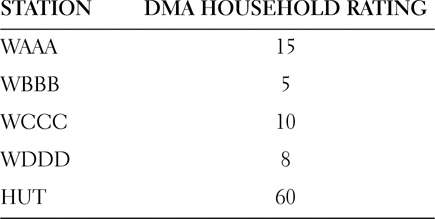

• Designated market area (DMA), those counties in which commercial stations in the market being surveyed achieve the largest share of the 7:00 A.M. to 1:00 A.M. average quarter-hour household audience.