Consumer Decision Making and the Role of Email

Up to this point, we have discussed the “how” of email marketing by reviewing the fundamentals of email design and common techniques for measuring performance. Let us now move to the questions of “when” and “what” to send. To answer these questions, we must possess a deeper understanding of consumer behavior. Accordingly, in this chapter, we first present a general model of the process consumers go through en route to making decisions about product purchases. Subsequently, we adopt the perspective of marketers who wish to influence or facilitate this process. From this perspective, rather than focusing on the steps consumers go through, we describe a “hierarchy of effects” model that focuses on the stages of a consumer’s relationship with a particular product or service brand. Throughout, we provide examples of how email can be used to achieve desired marketing outcomes by knowing where consumers stand in their decision-making process as well as the status of their relationship with a particular email marketer’s offerings.

Consumer Behavior

Consumer behavior is the process and activities individuals undertake for searching, purchasing, using, and disposing of products and services to satisfy their needs and wants. Some purchase decisions, such as buying a car or camera, may involve lengthy search and evaluation before a purchase can be made. For other purchase decisions, the process may be habitual, such as buying the same brand of orange juice every month, or impulsive, such as adding a pack of mints to your purchase at a checkout counter. Successful marketers can influence consumer behavior if they understand their customers’ needs and wants and can reach out to them with the right information at the right time. To do this, we need to learn more about the consumer decision-making process.

Consumer Decision-Making Process

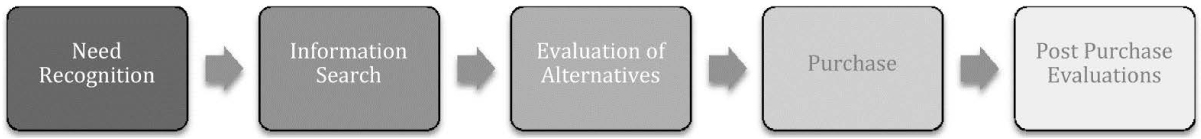

To understand the consumer decision-making process, we draw on the classic “grand models” (e.g., Engel, Kollat, and Blackwell 1968; Howard and Sheth 1969; Nicosia 1966; Olshavsky and Granbois 1979), and present a five-stage conceptualization (see Figure 5.1). The first stage of the consumer decision-making process is need recognition. Need recognition can be thought of as either a need to fill a gap or an opportunity to improve one’s situation. For example, if a household has used up its last box of Frosted Flakes, then there is a gap that needs to be filled, namely the replacement of a box of cereal. On the other hand, if a person owns an older model of a smartphone and learns of a newer version with improved features that would make the individual’s life more productive, then this would be a need based on an opportunity to improve one’s situation. Another way to think about need recognition is that it represents an individual’s motivation for wanting a particular product. For example, imagine you are planning a trip overseas and you want to focus on taking pictures. You realize that your current Canon digital camera is somewhat dated and you are aware that a newer camera would take better-quality pictures and have some additional features not currently on your camera. If photography is important to you and this trip is special, you might be highly motivated to look into available replacement options.

Figure 5.1 The consumer decision model

Once the consumer recognizes a “need,” they may engage in information search. Initially, this search might be “internal” and consist of examining memories of known or prior solutions (e.g., as represented by awareness of relevant existing products and services). As the individual exhausts what they already know, if needed, they may also conduct an “external” search for information from sources such as friends, coworkers (Onyemah, Swain, and Hanna 2010), magazines, social media (Cheong and Park 2015), and online reviews (Weathers, Swain, and Grover 2015). This stage is heavily influenced by which marketing elements capture attention and how the elements are perceived. Continuing our camera example, we may know that Canon has released several newer versions, but we may also know that there are other high-quality, innovative brands we have considered in the past such as Nikon and Sony. However, we may not know exactly what the latest options are, so we go to the Internet and search camera websites, retail stores, blogs, and other media to update our knowledge, thus conducting both internal (memory) and external (e.g., Internet) searches for information.

Once an individual has satisfied their need for information (which will vary from person to person and depending on how involved or high-stakes the decision is), they generally winnow the set of all encountered alternatives down to a smaller set of alternatives that meet some criteria for further consideration. During this evaluation of alternatives stage of processing, individuals tend to form strong opinions and attitudes toward the considered set of products or services based on what they have learned and through various methods of comparison. In our camera example, after researching different websites and perhaps speaking to friends, we may narrow the choice set to a newer Canon camera and a new Nikon, eliminating Sony and other brands. At the same time, Canon and Nikon may offer a few different models each that seem acceptable. Evaluating alternatives now involves coming up with a process for comparing our options, such as prioritizing (weighting) attributes or setting minimum or maximum values for attributes, and implementing a procedure for scoring the options. In some cases, consumers may use decision aids such as product configurators or choice-boards (Berger, Hanna, and Swain 2007; Berger et al. 2010).

After evaluating alternatives, consumers are on the precipice of making a purchase. In some cases, there may be unexpected events that influence a final purchase such as availability or sales. Once a purchase is made, the individual begins the process of experiencing the product and developing post purchase attitudes. In the post purchase stage, consumers are not only influenced by their direct experience with the purchase but also other things that they hear or see. For example, in our camera scenario, let us say we purchased a Canon model and then came across an article indicating the model we chose was nominated for editor’s choice on our favorite camera website. In such a case, we are likely to feel even better about our purchase decision. In contrast, if we found out that a camera we did not choose was named editor’s choice, we might experience doubts about our decision-making process and our camera. Brand managers are well aware of these possibilities and devote considerable resources helping shape consumers’ post purchase attitudes. For example, the brand may reach out and reassure customers about the wisdom of their purchase or provide them with new information about how to get the most out their product or service.

Of course, not all needs require an extensive search or evaluation process. For example, replenishing cereal or buying shampoo may not require significant search and evaluation beyond finding an available source at the lowest price. Additionally, the better the prior experience with a product, the consumer may bypass different stages of this model and move toward purchase.

Marketing Communications Objective: Hierarchy of Effects

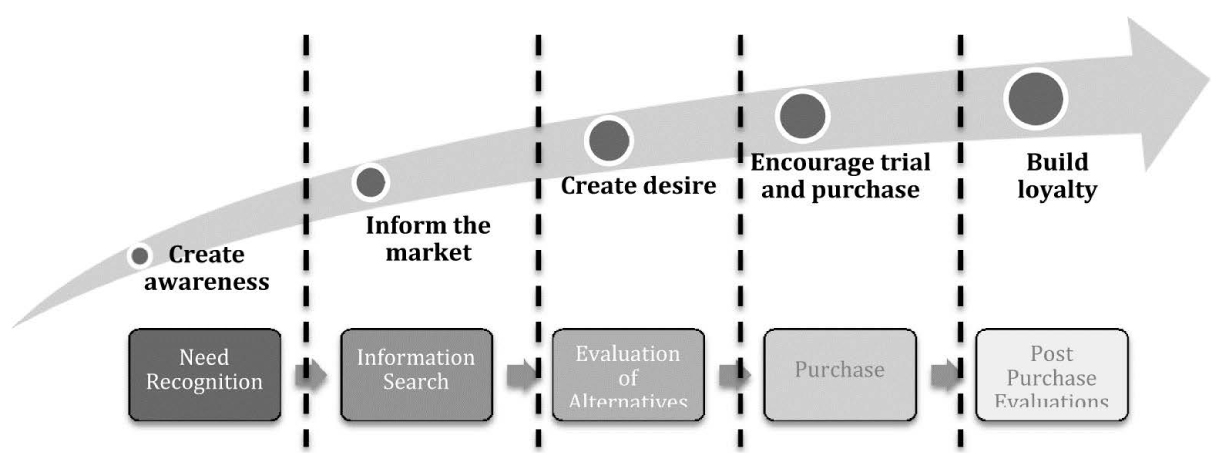

As you learn more about marketing and consumer behavior, you may encounter different models marketers use to understand and manage consumer behavior. Many of these models have similar formulations as the consumer decision-making process, except that they are conceptualized from the perspective of customers’ dispositions with regard to the marketer’s own product or service (McGuire 1978; Rogers 1962; Sheldon 1911). Perhaps the most well-known model of this type is the hierarchy of effects model (see Figure 5.2), which is a representation of how marketing communications may influence the consumer decision-making process over time (e.g., Lavidge and Steiner 1961; Ray et al. 1973). The term hierarchy refers to the notion that earlier “effects” (e.g., awareness) are thought to be generally necessary for achieving subsequent effects (e.g., inform the market). Whereas mass communication marketers can only roughly estimate where the average consumer may be in the hierarchy after a set of communications (e.g., based on ad-tracking results), email marketers may be able to precisely estimate where individual consumers sit in the hierarchy and thus customize subsequent communications.

Figure 5.2 The hierarchy of effects model

From a hierarchy of effects perspective, marketing communications must first create awareness (or reactivate awareness) in consumers regarding the product or service in question. This same communication might lead to a consumer recognizing an unanticipated need. In our camera example, imagine that we were not thinking about purchasing a new camera for our trip until we came across an advertisement for new features in a Nikon model that allows for easier, higher-quality photos in outdoor settings. In this scenario, Nikon has successfully created awareness for its new model while also helping us recognize a need. Marketers also seek to create marketing communications that inform the market of how their products and services work. This may be in the form of digital marketing (e.g., YouTube videos, websites, etc.) or a longer-form advertisement with demonstrations. For example, Nikon may post a video on its website or on YouTube in which the features of its new model are introduced and explained. Once the market is aware of a product or service and has an understanding of what the product or service does or represents, marketers’ objectives shift to create desire. In general, this means persuading consumers that the product or service is superior in some fashion to its alternatives (e.g., highest quality or best value or best fit). For example, Nikon could air a commercial in which it claims that its new model takes demonstrably better pictures outdoors or that it makes taking good pictures outdoors easier than other brands do. When consumers reach the point of desiring the product or service in question, marketers must design communications, promotions, or events in an effort to encourage trial and purchase. That is, the objective is to get the consumer to act on their desire. In the Nikon example, consumers may be offered rebates or a free camera case or they may simply be urged to “act now!” In the final stage of the hierarchy of effects, marketers seek to build loyalty among consumers who have tried or purchased the brand. For example, Nikon may engage in brand image advertising to nurture consumers’ perception of the brand as unique and favorable and thus self-enhancing. Similarly, consumers can be encouraged to explore idiosyncratic ways to use the product, thereby creating a greater sense of control, personal investment, and intimate knowledge of the product or technology (Kirk, Swain, and Gaskin 2015). Nikon may also take more direct measures, such as offering special amenities or access or discounts to existing customers. In doing so, Nikon is managing consumers’ post purchase evaluations and improving its chances of earning future business and avoiding the high costs and significant risks of trying to find new customers and move them through the entire hierarchy of effects (Swain, Berger, and Weinberg 2014).

Figure 5.3 The overlap of the consumer decision process and the hierarchy of effects model

Using Email Strategically

Marketers typically send emails to consumers in one of two ways: they either push emails directly in a one-to-many format or they automate emails to send to a consumer in response to a triggered action or event. Using a push approach is very similar to sending emails based on the hierarchy of effects. Marketers design an email to achieve a specific objective and send it to their list. However, by using automation, marketers allow emergent consumer behaviors to determine which emails are sent and how they are constructed, thus more directly informing the consumer decision-making model process. Savvy marketers should use both approaches. However, caution is required.

Marketers use push emails, or one-to-many bulk emails, to achieve specific marketing communications objectives. For example, a company launching a new product or updating an existing product may want to generate awareness and thus sends a bulk email to their existing customers (and/or rents a list of email addresses). Despite the bulk nature of the sender, the emails can still be personalized with consumers’ names or other information that the company has access to in its customer database or as provided by an email list vendor.

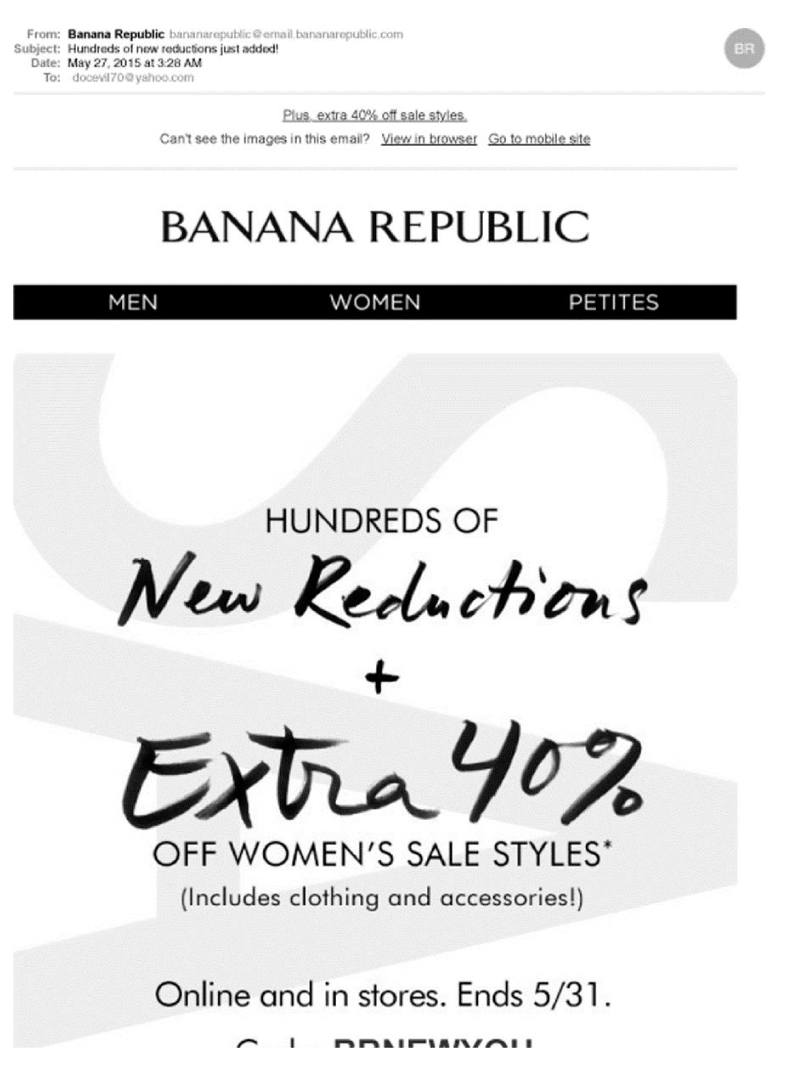

The most common push emails are for sales, lead generation, search engine promotion, and online media. Product or service emails that are consumer-oriented typically announce new products or offer sales promotions (e.g., see Figure 5.4 for a recent Banana Republic push email).

Figure 5.4 Example of a sales promotion email

Acquisition emails are focused on either creating new customers by offering a promotion (e.g., retail offer) or free service (e.g., access to white papers) or retaining existing customers (e.g., new product or service announcements, sales, conferences, etc.). These emails will vary in their look and feel depending on the type of business.

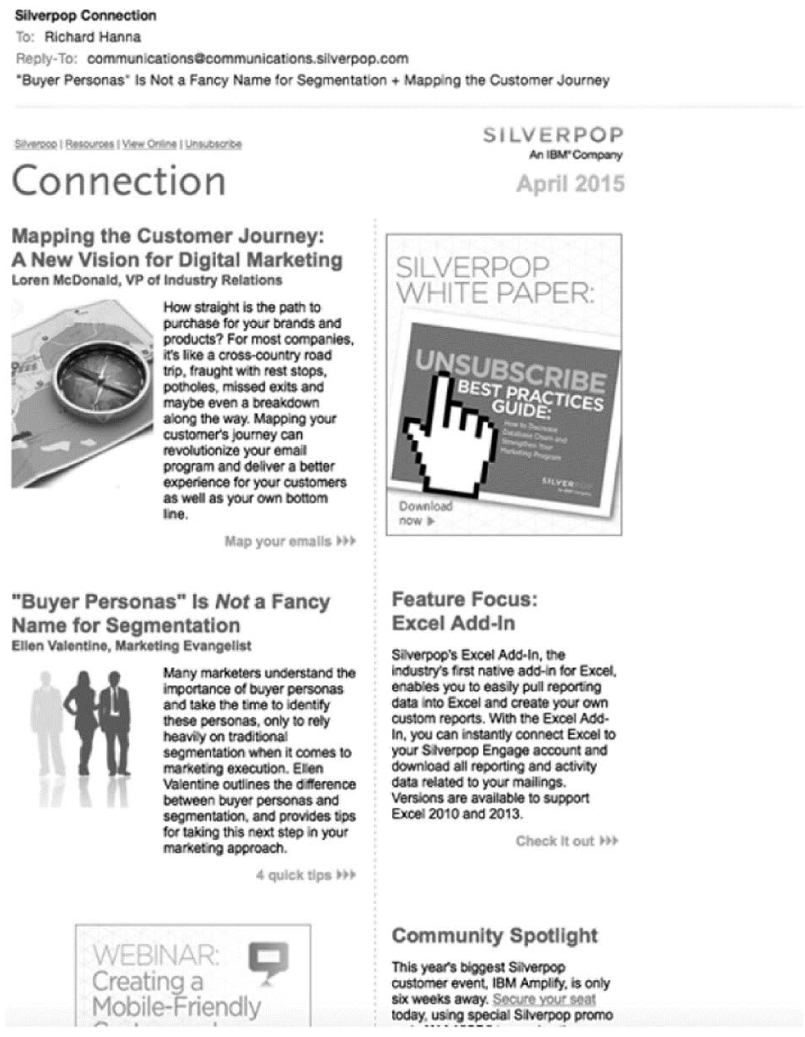

Some emails are focused on lead generation and less on immediate conversion. For example, MINI USA (the auto manufacturer) sends out monthly emails to their existing customers announcing updates and changes to MINI as well providing information about events and other activities (see Figure 5.5). Financial planners, lawyers, or consulting firms and other agencies often send out informational emails providing helpful content to try to generate traffic and engagement. For example, financial planners from Ameriprise may send investment tips (see Figure 5.6), while research firms may announce their latest white paper on a relevant topic such as B2B lead generation (see Figure 5.7). While the primary targets are their existing customers, companies sending these types of emails are also counting on their customers to share these emails with friends or other associates.

Figure 5.5 Example of lead generation and newsletter email

Figure 5.6 Example of services thought leadership email

Figure 5.7 Example of B2B lead generation using a white paper

Online travel agents and other search-engine-oriented companies may send an email announcing their latest deals to encourage their customers to use their search engine or stay top of mind for future searches. For example, Expedia recently sent an email promoting their low-fare alert (see Figure 5.8). Customers who are interested in this opportunity may use Expedia to search for more information. Or, just the idea of taking a trip might spark the use of their search engine to look into other opportunities.

Figure 5.8 Example of search engine email

Online media also send regular emails to their lists with content such as stories of the day. By bringing their readers to their website, online media companies generate advertising revenues from the banners that appear and other on-site marketing. For example, WEEI, a popular Boston sports radio station that also maintains their own sports news website, sends out “daily mashup” emails regarding the hot topics of the day (see Figure 5.9).

Figure 5.9 Example of online media emails

Automated Emails

Automated emails, or triggered emails, are emails that are set up to automatically send to the recipient as a result of a specific event. In other words, the marketer creates a custom email template with fill in fields for user data and other customer information. When a condition or a set of conditions is satisfied, the custom email is triggered and automatically sent to the receiver. The key difference between automated and push emails is that there are typically two types of triggers: action triggers and event triggers.

Action triggers are automated emails that are sent as a result of an action that a consumer completed. For example, shopping at a website and abandoning the shopping cart without completing purchase might trigger a reminder email. A customer who has not signed into their account for a long time may receive a welcome-back email. If a person has forgotten their login information, then the automated email that is sent with reset information is also considered a triggered email. However, perhaps the most important triggered email would be a “thank you” email. We take for granted the value of being acknowledged for a task or deed. Providing a personal email thanking an individual for completing a task, filling out a survey, or some other activity can mean the difference between a casual customer and loyal customer. Other, more functional types of triggered emails include purchase receipts and confirmation emails.

Event triggers are automated emails triggered by an event, such as an upcoming anniversary or scheduled event. For example, if a company wanted to provide a product discount that expires on a recipient’s birthday, the automated email could be programmed to trigger a set number of days in advance of the birthday date. A sequence of emails could then be programmed as reminders until the key event passes.

The key benefit of automated emails is that they are in response to consumer behavior. In other words, companies can potentially predict or determine the stage of the consumer decision-making process an individual is in and send a highly relevant email to help influence the process. For example, when an individual fills a shopping basket on a website, they are typically asked to provide an email address early in the process. Thus, when consumers fill a basket but never finish the actual purchase, an automated email is often triggered after a few days to remind the individual about the shopping cart and to perhaps offer an incentive or provide a rationale to complete the purchase. In this case, it is relatively clear the individual was in the purchase stage of their decision process and perhaps only needs a nudge to complete that process.

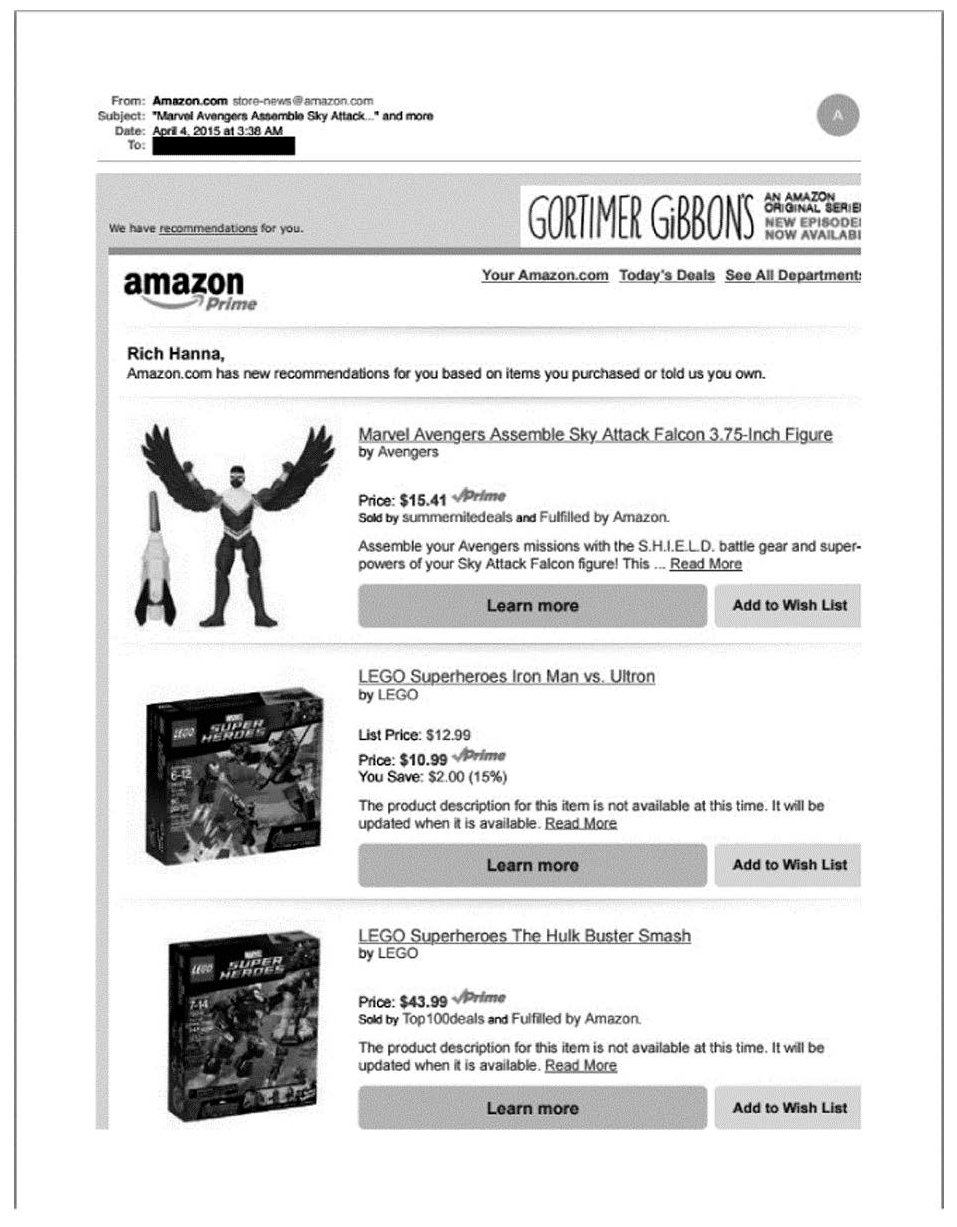

Tier 1 type commerce companies can apply their behavioral data with outgoing marketing by making recommendations based on past purchases or recent visits. For example, Amazon.com often will send emails making recommendations based on a prior purchase or even make a price change to a product that was browsed (see Figure 5.10). B2B firms also send product-/service-oriented emails.

Figure 5.10 Example of recommendation-based email (triggered)

Onboarding emails are another type of functional email that is critical to maintaining business. When someone joins your email list or signs up for a service or membership, they typically get an onboarding email that welcomes them and provides additional information. These are helpful emails that recipients can file (or not), which also confirm that the sign-up procedure was a success. Opt-in emails are considered onboarding as are initial offers for new membership.

It should be noted that most triggered emails, especially transactional emails, are exempt from the CAN-SPAM Act because they are typically in response to a customers’ request or action, and thus are solicited as opposed to unsolicited.

References

Berger, P.D., R.C. Hanna, and S.D. Swain. (2007). “Collaborative Filtering: Advertising Efficiency.” In Media and Advertising Management—New Trends, ed. Sabyasachi Chatterjeem, Hyderabad: ICFAI University Press, pp. 105–111.

Berger, P.D., R.C. Hanna, S.D. Swain, and B.D. Weinberg. (2010). “Configurators/Choiceboards: Uses, Benefits, and Analysis of Data.” In Encyclopedia of E-Business Development and Management in the Global Economy, ed. Lee, IGI Publishing, pp. 428–435.

Cheong, H. and Park, J.S. (2015). “How do consumers in the Web 2.0 era get information? Social media users’ use of and reliance on traditional media,” Journal of Marketing Analytics, published online, September 7, 2015. doi:10.1057/jma.2015.9

Engel, J.F., D.T. Kollat, and R.D. Blackwell. (1968). Consumer Behavior,New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Howard, J.A. and J.N. Sheth. (1969). The Theory of Buyer Behavior. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Kirk, C., S.D. Swain, and J.E. Gaskin. (2015). “I’m Proud of It: Consumer Technology Appropriation and Psychological Ownership.” Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 23, no. 2, 166–184.

Lavidge, R.C. and G.A. Steiner. (1961). “A model for predictive measurements of advertising effectiveness.” Journal of Marketing 25, pp. 59–62.

McGuire, W.J. (1978). “An information-processing model of advertising effectiveness.” In Behavioral and Management Sciences in Marketing, eds. H.J. Davis and Al J. Silk. New York: Wiley, pp. 156–180.

Nicosia, F.M. (1966). Consumer Decision Processes: Marketing and Advertising Implications. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Olshavsky, R.W. and D.B. Granbois. (1979). “Consumer decision making—Fact or fiction?” Journal of Consumer Research 6, pp. 93–100.

Onyemah, V., S.D. Swain, and R.C. Hanna. (2010). “A Social Learning Perspective on Sales Technology Adoption and Sales Performance: Preliminary Evidence from an Emerging Economy.” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 30, no. 2, pp.131–142.

Ray, M.L., A.G. Sawyer, M.L. Rothschild, R.M. Heeler, E.C. Strong, and J.B. Reed. (1973). “Marketing communications and the hierarchy of effects.” In New Models for Mass Communication Research, ed. P. Clarke. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publishing.

Rogers, E.M. (1962). Diffusion of Innovation, New York: Free Press.

Sheldon, A.F. (1911).The Art of Selling, Chicago: The Sheldon School.

Swain, S.D., P.D. Berger, and B.D. Weinberg. (2014). “The Customer Equity Implications of Using Incentives in Acquisition Channels: A Nonprofit Application.” Journal of Marketing Analytics 2,no. 1, pp. 1–17.

Weathers, D., S.D. Swain, and V. Grover. (2015). “Can Online Product Reviews be More Helpful? Examining Characteristics of Information Content by Product Type,” Decision Support Systems 79 (November), pp. 12–23.