3

What Information Do We Need to Pick the Right Product?

3.1. Choice of products

3.1.1. The problem with choice

The powers of disinformation, in other words, the ways currently used to attract consumers, often lead to them making the incorrect choice, product-wise. What the customer thinks they know prevents them from learning. When there are too many choices, there is no choice. The more important the choice, the more uncertain it is and the more it neutralizes the consumer.

Strictly from a usage point of view rather than one of marketing, the usage cycle, measured based on the standard lifespan of a “product”, starts with research and by choosing a method best suited to the use.

However, with usage reflecting, by definition, only part of the reality, we should not view consumers as a single entity against the competitive market. Both the consumers and the market are mutually influenced by a variety of socio-economic factors.

It is, however, necessary to focus on identifying and examining the practical relationships which exist between the different types of consumer-users, the various product models and types offered as well as the commercial and social environment that surrounds them (types of sale methods).

In a somewhat schematic way, the process of choice in terms of usage must go through three main phases. These correspond to the following questions which may go through the consumer-user’s head:

- – What am I using the product for and what are the essential requirements?

- – What is the specific type of material among those offered on the market that is best suited to my use?

- – Finally, which of the product models currently offered on the market can best satisfy my own usage requirements (choice criteria vary with each consumer)?

It is also worth noting that the pathway above does not single-handedly bring the consumer to the ultimate choice and a final purchase decision as a number of other key elements regarding the estimated value of the same product type are often at play.

The hierarchy between the choice criteria is dependent on the consumer-customer’s last resort. Customers are not all the same; their needs and desires are diverse and are frequently changing.

The image of “freedom” that the open market publicly portrays can actually hinder our ability to be aware of the purposes of consumer “activities”. So what information channels do we use to make the right choices?

Each of the questioning phases mentioned above require information which can help, support or lead to a choice that ensures habitual usability. In terms of the product’s ease of use alongside other choice criteria, we must look at the genuine usage performance of information channels on the products that are currently available.

Can we examine the efficiency and the practicality of vacuum cleaners by seeing them “tested” for a few minutes on 1 square meter of carpet for a few dust particles in the buzzing atmosphere of a department store or a living room?

The issue of choice stems from the information on products. Most of the time, the consumer comes up with a demand which more or less equates to: “I want to buy a vacuum cleaner, tell me which is the best?” and inevitably Satisfactory the process of choice and the information it uses will work hand in hand, along with marketing concerns.

Satisfactory information on products inevitably goes through a complicated and difficult process.

It is summarized schematically as follows:

- – In terms of dust removal, for example, what are the requirements in terms of my usage?

- – What are the various existing dust removal methods? What are their main advantages and disadvantages? And among these, which type of product (or service) will guide me towards my choice?

- – What are the different items of this type available on the market? What are their specific advantages and disadvantages?

- – Among them, which models are best suited to my usage?

- – Finally, among these models, if there are several, which item will I finally choose, given the relative importance that I give to such practical, financial, aesthetic or symbolic aspects?

Each of these phases in the choice process requires a level of suitable information. Each of these levels must have distinguishing elements to help make a decision. Choice criteria and information elements go hand in hand, from the most general to the most specific.

3.1.2. The process of choice

Depending on the disposition of the consumer, the latter can display:

- – healthy curiosity (learning about something);

- – fear (of not being on trend);

- – reluctance to consider another choice;

- – inertia and passive resistance to innovation;

- – refusal, by bias or fear of risk.

The consumer favors information which comforts and confirms their predispositions and beliefs. This reasoning, by overconfidence, can have serious consequences on the choice of products or devices made, for example, when based on the consumer’s disposition. This gives less importance to the other arguments. This means only considering information that confirms your own beliefs, listening only to sources likely to support them. It is staying true to your beliefs, even if your arguments are wrong. It is giving the most importance to the first piece of information received, which originates from your own beliefs. It is asking a question without waiting for the answer, only taking into account your personal predispositions!

Choice is often unwise. The consumer does not take the time to determine their true requirements for use. It is a type of intellectual laziness. We stick to our habits, for example, purchasing and re-purchasing the same brand. We no longer reason, and we robotically buy things.

Although choice involves both reason and emotion, it is mainly based on emotion. Too many choices hinder choice. Too much detailed information negatively affects decision-making due to the difficulty in prioritizing the factors.

The consumer must persuade themself that their purchases are suitable. After initial consideration, emotions are at play. This helps the consumer to decide.

Choosing a product on the market means solving a problem that must first be formulated according to its use. Then, from this correct formulation comes the types of information elements that can answer the questions of the consumer-user. Unfortunately, such a process seems too complicated to customers, who want a process that involves the least amount of effort. The first question concerns the service functions and, in particular, the essential services.

To reuse the above example, we do not often pick a toilet for its seat or its flushing mechanism. We may need to consider the potential consequences of the lid or the flushing mechanism we choose, but this may be of importance further down the line, especially for those who benefit the most from comfortable facilities.

It is the user who handles and operates the product, maintaining and changing it according to their requirements. Even if the lid and the flushing mechanism are far from being the only components of the product, it is still necessary that materially these subcomponents to be installed are compatible with the existing elements a priori (the bowl and tank, for example). This is a brief example of a problem of choice to be resolved. It is equally based on intellectual function and appropriate information, which can be taken advantage of.

We must refer to a “pedagogy of choice”. Without this pedagogy, the actions of information in all directions could be nothing but a waste of resources.

Schematically, the first question is therefore: “what are the requirements to be met that relate to my own usage?”

The second step involves looking at the various types of existing means, their main advantages and disadvantages in the same way as those previously identified (i.e. apart from strictly technical or commercial aspects): “which of the existing types should I orientate my choice towards?” It is worth noting that orienting one’s choice does not mean choosing definitively.

The third step becomes much more concrete as it finally brings tangible products and items into play. If they are not observable, they are represented by an image. The consumer therefore focuses their interest on the different models available or the different types of prospective products.

The advantages and disadvantages at stake become much more specific.

The question then is: “which models, among those offered, best meet all the requirements of my own use?” Note that the answer to this question could be: 40 models, 4 models, 1 model or 0.

The last step, where we make a definitive choice, therefore depends on the relative importance which is attached to such functional or extra-functional aspects (aesthetic or symbolic), to a particular aspect of user cost related to the likely usual longevity and the expected “service quantities” over time, to any aspect of after-sales service or the possibility of maintenance in the long term.

The pieces of information required at each step are becoming increasingly specific as the notion of “product” becomes more differentiated until it becomes an item to buy.

On the contrary, a definitive choice should not necessarily be confused with an immediate decision to buy. The consumer has the freedom to reconsider the elements at play during the different steps insofar as the latter or the penultimate step cannot lead to a possible or satisfactory choice.

The consumer may also delay their choice by hoping for a more satisfactory product offer (later, or at a competitor’s).

However, a choice must be made based on research, or even work. It should not be something that is imposed upon us.

3.1.3. The frustration of choice

Given the plethora of almost-useless information available when making a choice, shown by various powers (see Volume 1), the consumer often finds themselves frustrated. Without proof or a demonstration of the product, the consumer must try to believe the information. There will be discussions and negotiations, not on the product but on the information!

Making a choice really does require a certain amount of courage: electric, diesel, petrol or hybrid? Lawnmower or lawn tractor?

In some cases, the activity of choosing requires more effort than the benefits of using the product. The choices are entangled in a maze of rather confusing possibilities and these possibilities have numerous cloudy paths. Doubt, hesitation and indecisiveness become the only possible resolutions.

Consumers no longer want to waste time facing the infinite choices available. A brand renews their confidence!

Making a purchase is like voting. Not buying means you oppose such a product on the market. Choosing is the anxiety of being wrong or having too much confidence! The risk is either thinking too much, or badly, or not enough.

Is it possible to hope to choose the perfect product, the universal panacea, the one and only one that fully meets all the requirements, being the best for everyone?

The right choice of such a product only represents a short period of the relationship between the chosen product and its users. Therefore, each individual subconsciously knows that after choosing a product they are free to enjoy the product’s “happiness”, which is defined as “what is valued by the community” by the ideals of the time. With better choices, there would be less discontent, dissatisfaction and feedback, which lead to less waste and mismanagement. The decision to select one product from hundreds of others is a complex affair. The choice is often made, initially, on the supposed quality/price ratio of the products, on the simplistic image it portrays, without looking further at the “quality” (what quality?) or at the “price” (purchase price and not the “cost of use?”).

The consumer must take in a considerable amount of information, however useless or misleading. Unfortunately, this issue is not helped by computers and the Internet. When searching for a product, the buyer often does not know where to look, so any relevant information they come across appears to them as trustworthy. The consumer prefers to rely on their more or less immediate emotions, to leave it to chance, seek advice or align themselves with the choice of others. It is difficult to predict how much the product will satisfy its purpose. It takes some time for reflection depending on the type of products, the circumstances of purchase, the time available, the price, etc.

Without any information, the consumer must rely on their own intuition. There are different types of purchasing decisions:

- – authoritative decisions: one single person decides on the purchase;

- – majority decisions: the majority are in agreement, for example, when buying a boat;

- – minority decisions: a few family members make the decision, for a dishwasher, for example;

- – unanimous decisions: all the family, for example, when buying a house.

And here are some more or less risky methods when it comes to decision-making:

- – studying more seriously, researching better;

- – putting everyone’s ideas together;

- – trusting your first impressions;

- – taking advice from friends;

- – being guided in your thinking process;

- – asking another person to decide for you;

- – debating and negotiating;

- – looking for a consensus, making compromises;

- – relying on chance, tossing a coin;

- – not deciding straight away, and instead waiting to make a decision as to whether to buy the product or not.

Note that a group of people (often not necessarily competent) is often asked to decide instead of those that are more informed or responsible.

As decision-making requires a significant number of factors, information systems must be used (see SIP information system of the ICC in the Appendix). These systems must use usage analysis results for product selection.

Choosing is a poorly thought out activity due to products’ lack of relevant information regarding usage and the environment, whatever one may say and think about it.

The whole market is a huge system of bad decision-making risks, from the design to the decommissioning of products. The consumer has neither the intellectual means nor the time to properly think things through. Making a final decision is a matter of human responsibility and it is important that it remains so, whether regarding the choice of a product or, more dangerously, for military decisions.

3.2. What is usage?

3.2.1. The problem with usage

Qualities of usage are indispensable. The interactions between users, products and the surrounding environment are not very often considered. This lacks an intellectual movement to promote the field of use. This is also the case for industrial design. Neglecting basic use criteria does not come without consequences. For many consumers, as well as engineers, technicians, marketing managers, beauticians or vendors, the use poses a priori no “problems”: it is only a matter of common sense! It even happens that “providential” common sense is mistaken. It is enough to be confronted with control devices or visual control systems for a simple electric stove, a Hi-fi system, a car dashboard, a bath mixer, a subway tickets distributor or a website!

How many false maneuvers, disagreements or accidents (even aircraft problems) caused by negligence could be avoided?

For example, accidental slips in a bathtub, where more showers are taken than baths, cause injury. A significant proportion of accidental deaths are caused by domestic accidents, among both children and adults1.

Contrary to immediate economic profitability activities, those with high accidental risks or military combat, domestic, public or semi-public activities are not often the subject of thorough usage studies.

With the change in trends and the rapidness of production methods, new product types and models (such as connected devices, robots and, before long, driverless cars) suddenly appear without reliable usage studies or information for consumers to make a choice. Unfortunately, their commercial attraction rests more on the “novelty notion” than on the better usage qualities in comparison to the products they supersede.

Taking into account the differences which separate individuals, including both cultural and physical aspects, it seems impossible that one product can satisfy everyone. Admittedly, some products are introduced into the market with the intention of attracting the largest number of targets possible, but they can only be successful in a monopoly situation or if they work to constantly refresh their audience by using clever marketing and publicity strategies.

3.2.2. The field of use

3.2.2.1. The field of use: products/users/environment relationship

Figure 3.1. Products/users/environment relationship: definition

Figure 3.2. Products/users/environment relationship: interaction

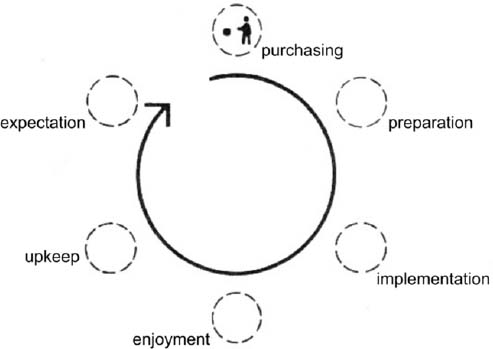

Figure 3.3. Usage cycle

Figure 3.4. Use cycle

3.2.2.2. Towards a usage science

The field of use is defined as the relationships and interactions that are established between consumer products, their users and their mutual environment (Figures 3.1 and 3.2).

Products, users and the environment make up a dynamic and complex system of which the objectives, resources, functions and characteristics are the subject of investigation in terms of usage.

Located at the crossroads between several scientific fields, although none of them completely cover it, the field of usage must call on an interdisciplinary approach.

Within the consumer product existence cycle, the following main functions appear (Figure 3.3):

- – the choice of means to implement in order to reach the targeted goal;

- – the acquisition of these means or their enjoyment, as well as the deferred commitment of the expenses incurred;

- – the introduction of these consumer products into the living environment

- – whether these products work or not;

- – the use and enjoyment of the service provided, according to a process described below;

- – the maintenance of these consumer products so that they provide the desired service;

- – the decline of these products by conventional means, accompanied by a non-utilitarian reassignment or a rejection of the product in the form of waste or recyclable material.

As for the use cycle (Figure 3.4), in space and time it is often a repetitive process which begins each time the user confronts a product in order to receive a desired service. The main functions performed are usually as follows:

- – access to the product: to go where it is, familiarize oneself with it, take it out of its storage medium, etc.;

- – the preparation of anything which needs implementing: installing a device, attaching accessories, supplying energy, preparing the necessary tools or the material to be used and meeting the requirements – documents, permits, payment, the user’s physical conditions, etc.;

- – implementation: operating, ordering, directing and controlling operations; handling tools, mechanical devices or material, processing information, waiting for the expected result, looking at accidental risks, etc.;

- – the enjoyment of the service provided and the resulting effects: enjoying a new state of things, the produced effects, using the resulting products, being exposed and exposing others to adverse effects (pollution), etc.;

- – maintenance for future use: throwing out waste, cleaning the products and the environmental surfaces, reassembling the dismantled parts, keeping them in good working order, repairing damage, putting a product on hold, tidying the products or leaving them in a given place, protecting them against external agents, etc.

What is meant by a “consumer product”?

3.2.2.3. A functional analysis of the consumer product

In contrast to an object from a museum or a sculpture, to a project in a plan or model, to the merchant product in a catalog or at its place of sale, an object in a use situation is never isolated or inert. It establishes between itself its users and the environment and has relationships of great complexity.

Due to its material nature and, in general, its technical functioning, the consumer product finds itself inserted in the physical environment where it becomes a component of a more complex material system: the refrigerator is usually installed in the kitchen, the garbage chute fits into the space of a vertical shaft of a building, etc.

This physical integration into the operating environment inevitably leads to an occupation of space, technical links, a circulation of material, energy or information, as well as “neighbourly” relationships with the components and environmental beings.

What do we mean by users? In a general manner, any individual, who, in their living environment, comes into contact with a commercial product must be considered as a user. Users are not only, as is customary to suggest, immediate and “normal” users. In certain cases, the common relationships which determine the existence of users are merely temporary, occasional or completely involuntary.

In any event, these relationships must be understood and appreciated, depending on the significance of the role they play in the users/products/environment system.

For example, a housewife grates celery in her kitchen. Her family or her neighbors “benefit” from this despite not directly being the product user. The guests who will taste the celery rémoulade all appear directly or indirectly as users of the machine that grates or has grated the celery. Users are all those who:

- – have a physical or sensory relationship with the physical object;

- – profit, deliberately or not, from services that result from the main purpose of the product;

- – pay the expenses incurred in the implementation of said product;

- – are subject to the nuisance caused by the product and the use made of it.

3.2.2.4. User-operators

User-operators perform certain active or receptive actions, which are caused or dictated by the instructions of the consumer product.

In more or less immediate contact with certain parts of products, they must perform complex operations and they are sometimes subject to certain undesirable effects. These operations are made up of tasks which require their share of bioenergetic, psychosensory and intellectual capabilities.

The user-operator provides the work; they carry out actions and adopt positions that they control due to the information they collect for themself, the product or the environment.

They exchange with the environment, by fulfilling its operational functions, built from two “essential substances”: energy and information. The user-operator must perceive, learn, estimate, decide and act in space and time.

Among these user-operators, we distinguish between:

- – users who use or are led to use all or part of the product, by working with regard to the essential function of its use. This is the case, for example, with the housewife who grates celery, with the person who makes a telephone call, or with the doctor or nurse in the hospital;

- – “para-users”, who use the product but do not have a relationship with the service it provides. They use it for other purposes and sometimes in an indirect, accidental way, or unwillingly. Examples are a child who plays with a juicer, the mother who tidies toys, the repairers of a service post-sale, maintenance workers, removal workers, or even a girl moving a lawnmower to get to her tricycle.

3.2.2.5. User-beneficiaries

They use, profit from or enjoy the services provided or the results obtained by the use of the product.

These services can be desired, accepted with resignation or even provided against their will. Beneficiaries are the people who eat the celery which has been grated or drink the pressed orange juice; the patient whose illness is regressing or worsening thanks to the hospital; the injured person transported by an ambulance or the prisoner transferred by a police van.

For user-beneficiaries, the result of the service provided seems to be like a form of response to a requirement, or at least to what they perceive, feel or judge as such. This biological, emotional or social need is expressed in terms of the actions to be performed in the context of a more general activity; the latter is itself recognized in all cases as a necessity of higher order.

These necessities are in fact dictated as a result of successive derivations, and it results in a considerable gap between the current needs, sometimes seen as practically essential, and the primary necessities of survival, security and physical and mental well-being.

In any event, the beneficiary will find themselves more or less satisfied by the result obtained to the extent that it meets or does not meet its own requirements. These requirements, which are conditions required by the user, have a tendency to make the characteristics of the desired result more specific. They express themselves in qualitative and quantitative terms, like, for example, the following beneficiaries:

- – to drink orange juice every morning, at breakfast, you need a glass of juice (about 20 cl) that is clear, without seeds or pulp;

- – to maintain the lawns surrounding the house, a mowed lawn, including border edges, and well-kept flowerbeds, trees and trunks, is required, without letting the grass become uneven or torn.

The nature and the thresholds of these requirements can vary considerably from one beneficiary to another, according to their cultural or ethnic origin, social sphere, physical conditions, age, gender and mental development. They can also vary in time for the same user. Some of these requirements are essential when they arise from physiological and psychological considerations for individuals, or from ecological considerations for the human community and the environment.

However, other more subjective and fluctuating requirements fall within the fields of affectivity, symbolism or aesthetics.

3.2.2.6. User-consumers

They cover all or part of the costs related to enabling the enjoyment of the product as well as its deferred costs.

The financial perspective is clearly insufficient to account for the reality of costs, particularly because of the distortions and fluctuations in current socio-economic values.

In addition to the financial budget of consumers, who are essentially economic, their budget-time, budget-space and energy budget are also established in relation to the limited resources available to them – their lifespan, living space and energy substances.

3.2.2.7. Counter-beneficiary users

Involuntarily, they are subject to the consequences of the use of the products made by others, without expecting any service. Counter-beneficiaries are thus exposed to the harmful effects, accidental risks or nuisances of any kind that are generated by commercial products.

This is particularly the case for people who can hear their neighbors’ lawnmowers, or their loud electroacoustic music.

This is also the case for pedestrians and residents immersed in urban traffic, non-smokers who must stay in the smoking atmosphere during some meeting or conversation, and living organisms in the rivers that are polluted by our sewers.

The requirements of the counter-beneficiaries inevitably intervene in a restrictive manner in the face of the requirements of the beneficiaries. In particular, they oppose the choice of the means used and, as a last resort, the needs recognized as such by the beneficiaries.

3.2.2.8. Real users

In reality, these different categories of users very rarely exist so clearly. The various aspects which characterize them are in fact made up of a multitude of user profiles which correspond to each usage situation. These various types of users intervene in the game of the relations of use, by attributing more or less relative importance to some of their requirements, to certain human, social, ecological or economic factors2.

3.3. The indispensable: usage and environmental factors

3.3.1. Usage qualities

Usage qualities have an objective existence which does not depend on simple personal judgments like perceived qualities. The complexity of products often leads to frustration with use, even stress. This is not only the case for technological and IT equipment, but also for tin cans which are difficult to open, corks which are difficult, even impossible to unscrew, remote controls which are too complex, and hard to read notices.

If the need for simplicity is valued when making a purchase, it is even more so when it comes to using the product: the user no longer wants an unreadable or incomprehensible instruction manual. They do want devices that work immediately, without resorting to any help or, worse, to a “hotline”. Many products have been created without any thought into the daily reality of users and the usage quality for them! Users do not want to waste their time on tasks which bring them no satisfaction, which force them to rack their brains and, in addition, reveal to them their limited knowledge and skills!

The majority of daily products do not require hours, or even weeks, of learning and practice. Who can dedicate time to learn about using a product? These are design flaws, often unjustly blamed on users suspected of “not knowing” or “not understanding anything”. These errors are due to a lack of consideration regarding the very large variety of users who differ according to: age, gender, mental state, disabilities, physical abilities3, biomechanical abilities, gestural or operative fluency (right-handed/left-handed/ambidextrous), ways of life, cultural habits, religious dress, character, behavior, specific habits and circumstances. They can also differ according to a user who is: distracted, not meticulous, careless, manic, with playful or sensual inclinations, in a hurry or has free time, in a daily routine at home, in an occasional situation with a third party, depending on the type of enjoyment of the premises (property, long- or short-term rental, semi-private use), sensitivity to sources of embarrassment or nuisances (noise, smells, drafts, reflections, lack of light), aesthetic sensitivity (presence of houseplants, domestic animals), etc.

The use of a product is not unrelated to other complementary equipment or products, environmental conditions or constraints, or even the type of users or methods of use. Similarly, the user could be a regular or occasional user, or simply a beneficiary of the service provided. The place of use can extend to unique places, influencing the storage, installation, transport and security.

Use marks the end of the product’s journey. Progress must always be centered on the user and the environment. An innovation must always be an improvement of the quality of the product’s use or services, a source of progress which is not particularly technical.

3.3.1.1. Everyday life accidents

This information on accidents has been pulled directly from multiple sources4. It has been partially reproduced and mentioned as such. Everyday life accidents are numerous, but keeping an inventory is difficult. Research on accidents is certainly seen as intrusive and invasive on people’s privacy. Some information concerning the recalling of products by distributors and makers due to accidents are rather inefficient. Their virtual absence on the Internet testifies to this.

Nevertheless, this information remains relevant in the choice and use of products and amenities.

3.3.1.2. Elderly people5

France already has a population in which almost 6 million people are older than 75. This will have doubled by 2050. For elderly people, life becomes more demanding on a cognitive level. The “silver economy” only offers products that are too “technological”. It does not necessarily respond to the daily needs of an elderly person. They do not want to use a product which has the image, “for an elderly person”. Certain products and amenities are too medical, or too technically complex for use.

For the over 80 years, the expected innovations could be the detector of Parkinson's disease, the electro-simulator, perhaps even the robot-assistant, the dream of the engineers.

However, the industry must not only target this age group. The “silver economy”, the economy of the gray-haired, could interest all users, with varying disabilities, even those who are in good shape. Other users could profit from products which are easy to use and comfortable. “The economy of the gray or white-haired” is not just to attract a particular “audience”, but a whole domain for designers, relating to the ease of use of products, well-being and the quality of life in various establishments or at home. Unfortunately, we hear more talk about intelligent homes than retirement homes!

3.3.2. Environmental qualities

The weather is milder now than it was hundreds of thousands of years ago6,7. Many scientists only focus on the last 150 years! Therefore, let us keep a cool head on global warming. Ignore the brainwashing, the false proof, the exaggerations, the pseudo-scientific demonstrations, the extremism, the prejudices, the uncertain opinions and the catastrophism. It is easy to dramatize the rise of the oceans that strikes the imagination.

Do people not want to guarantee the business of the fight against global warming? An onslaught against nature often leads not only to the removal of these nuisances but also to the birth of an anti-pollution industry: GDP growth will also signify a deterioration of the environment rather than an improvement. For example, climate change, which stirs up the media and excites the international political scene, is subject to manipulation and misinformation on the part of some people.

The “right wing” media maintain their alarmist beliefs, excluding the arguments of more moderate camps. The information is partial, biased, even rigged. It is a concoction of unique and acclaimed thoughts and, more seriously, of several scientific errors. It is true that global warming will become a lucrative business. Industrial and commercial activity in developed or developing countries remains polluted, more or less. However, whether or not we believe in climate change, we must take advantage of it and pave the way for social and economic transformation, in order to lead us to a better, more just and equitable world.

We must, of course, change our behavior towards nature. Air pollution by dust and carbon particles, or by the emanation of toxic gases, must not be confused with the release of carbon dioxide. This is an inert gas which does not pose risks to the health of humans. If greenhouse gases have a significant impact on global warming, carbon dioxide is harmless on the respiratory system of living beings.

3.3.2.1. The environmental economy

The naive goal of the polluter pays principle is to determine who pays the cost of pollution. This principle is difficult to put in place and is therefore rarely applied. For water, for example, the consumer pays a tax on their water bill, which allows polluting industries to renew their installations. The market reduces nature to its commercial value.

3.3.2.2. Environmental efforts, a money-making business?

The dominance of the industrialized countries is obvious in world trade. The American government tries to prevent product imports from abroad, disguised as environmental protection. The environment is still elitist, more likely to interest the rich than the poor, whose preoccupation is primarily to feed themselves. Environmental efforts are therefore destined to improve the health of rich people rather than that of the environment. Would it not be better if it benefited both? Developed and developing countries do not yet have the same environmental considerations. Rich countries look for sustainable solutions to limit the effects of pollution, while developing countries first seek clean drinking water for the inhabitants and provide electricity. Developed countries must put in place more sustainable products and change their consumption patterns. Developing countries must not repeat the mistakes of industrial countries. They must start environmental measures now.

The main purpose of the economy should be ensuring the well-being and enjoyment of individuals.

We are saturated with eco-stuff and bio-stuff such as:

- – “ecological” tires (more kilometers traveled and less fuel consumption!);

- – “ecological” nuclear power plants that do not emit CO2!

Eat organic, drink organic, read organic, paint organic, organic make-up and make-up remover, pack in eco-expanded polystyrene and warm up with eco-fuel. Eat beef that releases tons of methane all day long! We are promised that all pollution problems will be solved! Green is a curiously trendy color! Environmental issues take precedence over issues related to use.

The good citizen who consumes and encourages the rise of the GDP has become the bad citizen of today, the one who damages their ecological footprint by consuming too much.

To change topic, exposure to asbestos continues to claim victims in France, with at least 2,200 new cases of cancer and 1,700 deaths each year. When will nanoparticles fall?

The air is becoming unbreathable – and not only in the corridors of the metro – but also near “air conditioners”. Consumerists are right. The stir caused by environmentalists and the courageous actions of some consumer organizations have raised the alarm. Now, doctors are concerned about the use of drugs, and governments about the use of energy.

Being close to the protection of nature does not mean protecting the environment, let alone knowing how to buy good products.

So, what types of pollution are directly or indirectly related to products (objects)?

- – Air pollution: in domestic environments, in the presence of substances, particles or gases such as oxides of carbon, sulfur and nitrogen, dust, radioactive particles, rejects of heating appliances, car engines, industrial installations, incinerators, etc.

- – Chemical pollution: includes chemical substances such as trichlorethylene, benzene, solvents, detergents, perfumes, dyes, some plastics, glyphosate and other even more dangerous molecules, etc.

- – Chronic pollution: residual pollutants, persistent after the disappearance of the source, radioactive waste, etc.

- – Diffused pollution: includes multiple pollutants in time and space, such as nitrates, pesticides, asbestos, etc.

- – Water pollution: toxic elements causing the destruction of fauna and flora, making the water unfit for consumption or bathing. These are waste, domestic, industrial, agricultural and viticultural waters with their phytosanitary products, intensive farming, fertilizers, nitrates and pesticides, hydrocarbons due to oil spills or ballast tank flushing.

- – Electromagnetic pollution: exposure to electromagnetic fields according to their power, their transmitted frequencies and the duration of exposure, etc.

- – Industrial pollution: significantly affects the ecosystem with its gaseous discharges, chemical or organic products, or its radioactivity, etc.

- – Light pollution: urban public lighting, with its excess light production, likely to affect biological rhythms, nocturnal activities and migrations of animals, sleep disorders, etc.

- – Organic pollution: caused by pollutants such as sewage, manure and sludge, for example toxic or even carcinogenic organochlorines (DDT), endocrine disruptors, insoluble, toxic or carcinogenic PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) which are now banned but still present in the environment.

- – Radioactive pollution: damaging biological resources, ecosystems or material goods, preventing the legitimate use of the environment. This is caused by the explosion of thermonuclear bombs (military tests), wrecks of nuclear submarines, serious accidents in nuclear power plants (Chernobyl, Fukushima, etc.), accidental releases of radioactive waste by the nuclear industry, etc.

- – Soil pollution: the infiltration of polluted water, of industrial or agricultural origin, linked to the use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides or animal droppings, etc.

- – Noise pollution: caused by human activities, such as transport (aircrafts, trains, automobiles), work and industrial activities.

- – Spatial pollution: caused by debris from satellites, spacecraft, launchers, etc.

- – Thermal pollution: resulting in an increase in temperature caused by cooling water discharges from thermal and nuclear power plants with damage to stream fauna, etc.

- – Global warming: caused by greenhouse gases and is the concern of the whole planet.

- – Visual pollution: plastic bags, signs and billboards, power lines, wind farms, etc. The overall cost of wind energy is more expensive than it seems because of the cost of equalization and storage reserves.

We consume more resources than the land can produce. We are plundering the natural resources of emerging countries for our own needs. It is a form of neo-slavery or at least neo-imperialism!

3.4. Evaluating the usage requirements and performances for choice

3.4.1. The analysis of usage/the criteria of evaluation

It is not a question of evaluating the products through points of view or from opinions, but to first move towards defining the factors of use evaluation criteria.

The functional analysis of use applies to the existing one, and more particularly to the favorable or undesirable consequences of the use of the different products in a multiplicity of real cases.

As the first link in the process of evaluation or product design, analysis is, strictly speaking, not a method we apply, such as a recipe. Its domain is that of use and use only; that is, it excludes the technical and instrumental functionality of the studied systems, the commercial potentialities of the goods and the desired image of the product.

In very simple terms, it is already about examining and dissecting the existing, the observable reality, the favorable or unfavorable concrete consequences of the relationships and interactions between: commercial products of the type of targeted products, users of different categories and surrounding environments. This first phase of general analysis is associated with a search for factual information on use: the general analysis, for a more or less specific type of product, relates to:

- – functional services: essential services, complementary services, any additional services;

- – operational functions of use, installation and maintenance: diversity factors of use cases that come from users (beneficiaries, user-operators, counter-recipients, consumers-payers), their activities, the environment use, environment and system states to use over time.

This preliminary phase of work continues with a more concrete identification in the field, in tune with the reality of the use of the products.

A study of use begins with an exhaustive inventory of the factors which come from the great diversity of the situations of use. The diversity of the cases of product use results from the multiple combinations which can exist between, on the one hand, the possibilities of functional services offered, and on the other hand, the factors coming from the various types of users, from the various types of conditions of product use and external environments, and also from the states of the system available for use.

Interview surveys are conducted on the qualitative aspects of real cases of use, on dissatisfaction and on the particular expectations of users, as well to actual pre-tests of use.

3.4.1.1. The reason for the study into dust collection methods: an example

The questionnaire survey is conducted for a triple purpose:

- – to gather clues about the importance of dust removal work and the commercial methods actually used – for the practical purposes of sampling the use cases and the products to be tested, then for weighing the analysis factors;

- – to recognize the sensitivity and the attitude of the users towards the problems of choice, use and qualitative evaluation of the products – in order to orient the informative messages to their current receptivity;

- – to identify the general or specific questions they wish for explicitly or not, to determine the information content to be extracted from the analysis and the comparative test.

It is not really a survey of satisfaction or motivation, but rather, a descriptive survey of cases of use and dissatisfaction. It is thus oriented towards the following aspects:

- – appliances and utensils owned and actually used, their advantages and disadvantages (as perceived or experienced);

- – previously owned devices and upcoming choices;

- – the individual problem of dust removal;

- – area, dust, time spent; who does the housework, what is dusted and with what, etc.;

- – reasons and sources of dissatisfaction, discomfort, inadequacy or even non-use.

It should be noted that it is equally significant to recognize what is not used and possibly why, than what is actually used.

3.4.2. How to evaluate usage qualities

In order to respond to the user-customer’s well-founded questions, it is necessary to have previously followed a similar path, and to have conscientiously sought out the required information. Because the latter do not disengage themselves and no one has really invested in it, the infused science is not appropriate and the source of information requires a methodical as well as considerable work (noticeable and important).

Faced with the diversity of usage cases (plurality of user-customers) and the multiplicity of product types and models of each type (richness of the offer), a double practice is required, that of the functional use analysis followed by the assessment of the actual qualities of use of the products.

The actual evaluation of the real qualities of use of the products does not require “negotiation” any more than the measurement of a physical quantity or a statistical value: know-how, intellectual integrity and professional responsibility should be, as in any field of a scientific nature, the guarantors of respect for valid recognized methodology, experimental conditions, instrumental tests, the relevance and reliability of criteria and scales of judgment.

Such work cannot suffer from the various pitfalls mentioned, while it is the responsibility of the study teams to consult, “exploit” or wisely involve, according to the resources of each individual, the various parties involved. In particular, it will be up to decision-makers concerned with product information to incorporate the “delicate” game of weightings, priorities and even “gray areas”, but under their own responsibility and in agreement (or not) with the point of view of other stakeholders.

Only then, at this level, short-term trade-offs between producers, distributors, repairers, standard-setters, informants and consumer organizations can become useful.

In fact, the requirements of use are difficult to evaluate all together or with shortcuts. The use is complex. While the merchant value is noble and cajoled, the use values, which are barbaric, only interest a few people. Affecting daily privacy, their evaluation is indiscreet, personal.

Indeed, the use of an object is not without relationships with that of other equipment or complementary objects, environmental conditions and constraints, or even types of users or modes of use. Similarly, the user can be either a habitual or occasional user, or they might simply benefit from the expected service. As previously noted in section 3.3.1, the place of use may extend to exceptional places that may affect storage, installation, transportation and security.

The evaluation of the qualities of use is based on criteria, evidence, facts, actions, realities, observations and demonstrations allowing incontestable certainties.

The extremely wide spectrum of these requirements of use covers in particular factors of:

- – psycho-physiological comfort;

- – psychological cost;

- – safety and hygiene;

- – nuisance, pollution, waste of natural resources;

- – economy of use (acquisition, installation, operation, maintenance);

- – affectivity (aesthetic and symbolic mediations);

- – etc.

The requirements of use are expressed in qualitative terms. They must be translated as quantitative performance requirements in order to be exploitable in the design and evaluation of products for choice.

It is a question of eventually being able to formulate the requirements and the expected performances of use. This consists of decomposing the range of requirements to a greater or lesser degree until there are less and less complex criteria for assessing the actual performance of the product candidates. The way is then opened towards the development of methods of usage tests and towards the formulation of the elements of information relevant to the use.

3.4.2.1. The methods of usage tests and test results

The main steps to follow are as follows:

- – sampling representative articles of the most specific types of products to be tested (with the most possible differences, where they are essential). At first, it is useless to test a half-dozen very similar products when just two or three are enough. On the contrary, the diversity of a priori different types can only be favorable when answering questions of the first levels and of the process of choice mentioned previously;

- – pre-testing and debugging of test methods for each of the elementary aspects identified in the analysis schema;

- – sampling of use cases;

- – detailed material conditions of tests, methods of measurement or qualitative assessment, record of observations to be kept;

- – comparative tests and systematic evaluation of the qualities of use of the product candidates for selection that are for sale, according to a rating scale (in general and in particular for the convenience of use);

A clear distinction must be made between:

- – possibilities and qualities of results for the services provided;

- – convenience and operational safety to use, install or maintain: analysis and evaluation of ergonomic expenditure and simplicity of use is generally the poor relation of technical tests and those of consumer magazines. However, in some cases, an “ergonomic cost”, which is too great an inconvenience for the user, who in general prefers to give up the purchased product rather than make the necessary manipulations for use. In other words, the customer leaves the invested capital unused, thus forsaking the paid and expected service of the product, rather than making the necessary expenses of manipulation. This explains the typical “bottom cabinet” products – appliances or kitchen utensils, for example (and with this, we only lose money and the dream of comfort…);

- – safety towards neighboring users and the surrounding environment;

- – factors of overall cost of use in the long term.

Figure 3.5. Camif rating scales (Camif 1980)

Table 3.1. Comparative table of the efficiency on bare floors of some vacuum cleaners (for rating scheme see Figure 3.5)

3.4.2.1.1. Efficiency on bare floors

When it comes to the actual quality of dust removal for various dust and particles (mineral dust, sand, bread crumbs, dog hair, sewing thread, fluff, etc.) by type of flooring:

- – it is impossible to characterize efficiency with a single figure or a note which applies to everyone;

- – dust removal efficiency should not be confused with the technical characteristics of the vacuum or air flow;

- – there must be a methodical recording of all the specific observations that can be exploited (for the choice of products);

- – there must be a translation of the raw results in terms of useful and appropriate information for each level of interrogation, the final source to draw on to contribute to the content of the various concrete means of expected information (selection guide, installation guide, user guide, sales pitch, product-article sheets, comparative table, catalog description, packaging and labeling of articles, etc.).

3.4.2.1.2. Calculation of usage values according to usage cases

A systematic division by degree of complexity leads to a grid of criteria in the form of a tree. This grid is systematically applied during usage tests as a whole, that is, between 30 and 40 characteristics per item, but with a more varied estimation scale for the advantages and disadvantages that are not really characterized. The same grid can be used by only taking out the salient or unfavorable highlights of each item in relation to the general advantages or disadvantages of the types of corresponding products.

This process is repeated from level to level so that groups of properties of lesser complexity emerge from properties of greater complexity.

The complex meanings of “input” (cost) and “output” (services) that contribute to the use value of a product therefore make it possible to make an objective judgment.

3.4.2.1.3. Value of criteria

According to the structure of the functions analysis, we will introduce limited criteria coefficients of a criteria group in each column.

These factors will indicate participation as a percentage of the criteria considered in relation to the criterion ranked above.

The criteria for allocating the coefficients of importance are made up of:

- – the purpose of use of the product, for example:

1) frequency of the function (average frequency of the service per phase of use);

2) duration of the function;

3) dependence on this product, that is, on the general function when the device refuses to work;

4) influence of this product on directly superior products;

5) number of sub-properties branching off from these complex properties.

- – specific user preferences, for example:

1) financial possibilities;

2) number of persons per household;

3) possession of other equipment;

4) local conditions;

5) habits, desires and social requirements.

It is not possible to establish one general system of coefficients for all.

According to the criteria relating to usage cases, one will value more or less each of the criteria.

It is here especially that we come across the issue of purchasing advice based on comparative tests. The “best product” does not exist. Different coefficient programs can reflect a target group in the market or the own usage case of such a consumer. The importance of limited criteria should only be assessed in relation to the criteria listed in the upper column.

3.4.2.2. Use value

Depending on the distance of the subject from the “average market level” (represented by a median drawn from the statistic parameters of the distribution), it is possible to define the relative use value that such a purchaser can expect from the considered product. This is a true assessment of value.

Each “cost” or “service” branch is calculated on a computer from the final assessment criteria, taking into account the coefficients of importance of each criterion; for costs and services, we obtain an overall evaluation linked to a certain typology of uses.

Different coefficient programs are therefore necessary to take into account the different requirements of each user. Each program corresponds to a certain evaluation of the use value of each product, which is represented in the form of a cost/service diagram.

Figure 3.6. Dust removal study of floors along with their borders, corners, skirting boards, under furniture, on stairs, as well as radiators, vertical slots and shelves (see Figure 3.7 scales of values)

Figure 3.7. Interpretation of value scales

Figure 3.8. Dust removal study for large bare surfaces with different floor coatings and different types of dust and particles

3.4.2.3. Usage value of 15 devices

Figure 3.6 corresponds to the dust removal study of floors along with their borders, corners, skirting boards, under furniture, on stairs, as well as radiators, vertical slots and shelves.

In Figure 3.6, the ergonomic cost is represented in relation to the service. Product no. 6 came in first. It needed the minimum amount of effort and handling for the best service.

Figure 3.8 corresponds to the dust removal study for large bare surfaces with different floor coatings and different types of dust and particles.

In Figure 3.8, product no. 35 came in first. It needed the minimum amount of effort and handling for the best service.

Other diagrams can be drawn from these basic evaluations.

3.4.3. The price and cost of usage

We must not confuse the purchasing price with the overall cost of use. For example, with a car, it is worth thinking in cost of use terms, that is, by kilometers traveled, rather than in terms of the car’s purchasing price. The notion of purchasing price, paid in cash or in monthly installments, can certainly attract the client-customer very easily. It lives under the influence of the laws of commerce and the customer–seller relationship. Admittedly, the price remains a barrier to cross (how much do you want to put down?) before one gains the enjoyment of the product or the service. However, it will be necessary for someone to cover all expenses incurred by the use of the product.

Besides the cost of the initial acquisition, the notion of the overall cost of use over time joins together: the cost of the delivery, the installation and implementation, the functioning, care and maintenance costs, indirect fees incurred due to malfunctions, incidents or accidents that could be caused by the product, as well as its expiry and eventual resale or market value, or even the cost of its decommissioning.

These costs must inevitably be related to the quantity of competent services (conditions of use and period of time). For a given product, a unique and determined cost of use cannot exist. In fact, the real cost of use, on an individual level, is situated within a range defined by the variation in cases and conditions of use: to give an example, the real acquisition and maintenance cost of a car that has traveled 230,000 km in 10 years has more than doubled from the initial price, in constant euros. We then add to this the costs of insurance, taxes, petrol, highway tolls, fines, parking and garages. We come to the conclusion that the social cost is probably higher than using a taxi or public transport.

In the case, for example, of large outdoor toys for communities, the purchase price comparisons are quite insignificant compared to the overall cost of use in the long term; their usual longevity is very irregular from one toy to another, and the number of children playing with each toy varies considerably. To allow a valid comparison between toy types or between different models, the overall cost of use must be related to the “child’s play time”, over the period of actual availability of the toys. Most toys are used alternately by 1 to n children at a time, for a certain time, according to a multitude of use factors (accessibility of toys, availability of other toys, environmental conditions, habits, mood of the moment, individual preferences for group games or not). The allocation of a number of play spaces, for each toy, cannot be specified a priori (according to a technical logic), but it is possible to determine from a long period of observation, the average of the numbers of children playing, weighted by the respective playing times and the duration of availability of the toys.

3.4.4. Habitual suitability

“Habitual suitability” and the specific usage qualities of a product can only be defined with respect to the game of “products/users/environment” relationships.

Standard employability does not guarantee habitual “suitability”. When the usage requirements and performances are satisfied, they participate in a feeling of well-being, pleasure and joy, accompanied by a desire to maintain this joy.

The habitual suitability of a product/contender for selection, in the majority of cases, can only be highlighted if a problem of choice is correctly posed (implicitly or better, explicitly formulated). A badly posed problem increases the risk of making the wrong choice.

Usage is complex: “iron” study (see in the following)

- – essential usage function;

- – factors linked to users;

- – factors linked to the elements of the used system;

- – factors linked to the use environment;

- – factors linked to the devices (steam iron).

3.4.4.1. Diversity analysis of usage cases

The diversity analysis of steam iron usage cases comes directly from multiple ironing activity combinations with the factors originating from complex real or highly probable “users/use environments/products”.

It is of the upmost importance to first understand, then to be able to refer at any time to the various elementary aspects which condition the use cases to be taken into account when designing the product.

3.4.4.2. Essential usage function

The technical function of such an object is to produce heat and to transfer it onto the fabric during ironing (by application and/or transitional pressing). The transfer of heat is then carried out either by conduction or combined steam projection.

On the contrary, in terms of use, ironing consists of making garments or upholstery fabrics de-wrinkled and primed.

A steam iron is a means only deemed suitable for an ironing board (a flat and horizontal surface) in the same way as a dry iron, a press or an ironing roller are for laundry pressing treatment.

Ironing, or rather, “uncreasing and finishing”, items of laundry is not a simple operational activity, but rather a relatively complex activity due to the multiplicity and sequence of operations to be performed. In other words, there is an art to it. In this respect, it can be emphasized that ironing is often experienced as a task or a duty, a constraint rather than a pleasant activity! Ironing is often performed within a family, by the same person, on a regular basis or at least several times a month or even several times a week.

What interests the user is obviously not the action of ironing, but rather the resulting effects, the result obtained compared to the expected result.

The quality of the ironing is characterized by the physical condition of the laundry and the absence of wrinkles (subject to sufficient know-how and the correct choice of temperatures).

Functional services are then conditioned by the types of laundry items, the characteristics of the fabrics to be ironed and the desired degree of finish. The implementation of certain ironing devices must not cause undesirable or irremediable effects to the garments (singeing, water staining, etc.). Thus, the absence of these negative aspects is added to the services expected by the user.

Finally, it should be noted that the iron is part of a system of indissociable elements necessary for the ironing activity (iron + support for ironing + accessories).

3.4.4.3. Factors linked to users

- – Gender and ironing experience: whether one is a housewife, single person, teenager, father, housekeeper, etc.;

- – ironing tasks: time spent, duration and number of items to be ironed (by an individual, family, third-party laundry services, regular or occasional ironer), ironing necessary to do when away from home (on holidays, while traveling, while staying at a friend’s house, etc.);

- – height and physical ability: anthropometric measurements, physical ease, bio-mechanical abilities to maneuver, lift, carry, the user’s dominant hand (right-handed, left-handed, ambidextrous), whether they are a teenager of small stature, physically disabled, elderly, mentally handicapped, visually impaired, etc.;

- – specific habits and circumstances: user who is busy or has lots of free time, whether or not ironing is a habitual or occasional affair, whether one is a nervous or confident ironer, ironing interspersed with other activities (such as listening to music, radio, television or conversation with other people), simultaneous monitoring, dress code according to the circumstances; snacking, drinking or smoking while ironing;

- – ironing requirements and the user’s individual ironing style: unconcerned or “manic” ironing, distracted, careless or meticulous ironing, whether or not the task is considered a “nightmare” or carried out with pleasure;

- – ironing positions: standing, sitting or semi-seated (resting on a high seat), or alternatively, both sitting and standing;

- – specific uses: moistening of the clothes before ironing, use of a press cloth or a spray while ironing;

- – sensitivity to the aesthetic qualities of products: perception of shapes, colors, textures, surface finishes, visuals, nature of the materials and state of cleanliness.

3.4.4.4. Factors linked to the elements of the system used

- – The type of ironing board: folding model, standard board with blanket and sheet, kitchen or dining room table, ironing board resting on the floor or on a table, table with a fine cotton, aluminum, metal or fleece cover, foam mattress screen “vapor barrier”, elastomeric mat, wobbly table, iron’s ground adhesion, negative effects of the iron (noise, vibration), stability and straightness of board cover, dimensional abilities for ironing and laying down material, presence of a retractable iron rest, a built-in electrical socket;

- – materials: sleeve board accessories independent of or included with the ironing board, refillable water funnels, bowl for press cloth, mineral remover, guide for the iron’s electrical cord, cleaner for the sole, descaling agent, etc.;

- – the mains connection proximity and accessibility of the socket, the use of an extension cord, presence of a switch and whether it is luminous or not, connection to a detection device or alarm in case of overheating and smoke, etc.

3.4.4.5. Factors linked to the use environment

- – Types of textiles: linen and delicate cloth, complicated shapes, flat linen or closed garments, large-sized clothing which could be heavy to handle when ironing, wet cloth or press cloth used to stiffen clothing;

- – place of ironing and laundry space/room: office, kitchen, bathroom, bedroom, hallway, living room, basement, attic, spacious or cramped areas, etc.;

- – conditions: ambient conditions with natural or artificial lighting, glare hazards, hygrothermal and aeration conditions, risk of electrostatic discharge, risk of leaving dust or staining, etc.;

- – related issues: risk of inconvenience by the smells or the impact of the iron’s noises or released steam, risk of falling or tilting which could damage the surface that the iron is placed on as well as the electric cord, whether or not the iron is laid on the ground due to surrounding activities, etc.;

- – storage and space available on the ground, in a room, in a shed, a toilet, in a closet, on a shelf, on a wall bracket on the ironing board, near a water tank, refilling and emptying the iron, cleaning the sole, aesthetic coherence with the surrounding environment, etc.

3.4.4.6. Factors linked to the devices (steam iron)

- – Types of steam iron, depending on the water used: demineralized water, tap water, a mixture according to the hardness of the water;

- – retractable, fixed or independent water tank;

- – vapor flow as a function of temperature, adjustable steam degree;

- – pressing option: steam jet control;

- – water spraying option: spot wetting control;

- – power supply, iron with electrical cord, iron with electrical cord with retractor and/or with storage;

- – rechargeable or not;

- – forgetting how hot the iron is, iron left or permanently unplugged with the minimum temperature selected, wear and tear of the electrical cord;

- – performance and instrumental characteristics: condition of the sole, risk of clogging (sticking together of fabrics, synthetic melting), scratching, degradation due to cleaning;

- – state of the device: new, repaired or old, apparatus with a missing or broken accessory, worn, deteriorated or has a damaged surface condition, cleanliness of the device;

- – there are limited ironing options for certain types of fabrics and clothing, malfunction of scaling of the vaporization system, deposition of limestone on the baseplate, lack of contact of the electrical cord, malfunction of the control devices, water leakage indicator lights working or out;

- – type of mains plugs;

- – blockage of the device;

- – device usage performance:

- - convenience and safety for operation,

- - convenience and safety for ironing a wide range of garments and clothes without any annoyances for the user,

- - convenience and safety to leave on hold or put away until the next use,

- - convenience and safety for cleaning and maintenance,

- - no nuisances or accidental risks to the surrounding environment,

- – overall cost of use in the future (for the records);

- – longevity of the steam iron under actual conditions of use: technical durability of all components, availability of accessories to be replaced, maintainability in case of accidental deterioration, estimated value, cost of acquisition, long-term use and maintenance.

3.5. Proposals for product information

3.5.1. Conditions and information requirements on products

At each stage or level of the choice process, the effectiveness and credibility of information to carefully choose requires the following conditions:

- – Requirement of availability and accessibility: the information elements required must remain available and within the user’s range, whenever and wherever they are needed. Deadlines or the methods of obtaining information must not slow down this process of issuing information at the expense of the choice of the decision-makers.

- – Requirement of relevance: each of the information elements made available must allow the customer to make a choice in direct relation to a key usage requirement. This excludes any global considerations oriented towards motivations or any pseudo-informative characteristics.

- – Requirement of comprehensibility: to be usable, the information elements must be formulated using clear and comprehensible language for all. This excludes coded designations, little-known acronyms, technical jargon, foreign terms or ambiguous vocabulary. The presentation of these elements must ensure the information is legible and must respect the limited abilities of the human brain to take in information under the conditions where this information is consulted.

- – Requirement of uniformity: to allow comparisons with equal opportunities. The information offered must be done so in the same way for each product with similar usage functions. Terminology, value scales or units of measurements, for example, must be shared by the same family of products and for those that require functional records/accounting to be guaranteed.

- – Requirement of comprehensiveness: to respond to the diversity and complexity of usage cases, the information made available must cover the highest number of usage cases possible and, in particular, all of the main statistically recognized criteria. 100% comprehension being unrealistic, it may be scalable beyond a minimum acceptable threshold (a negotiable all-party agreement, for example).

- – Requirement of accuracy and validity: to be trustworthy and to avoid making errors, each piece of data (characteristics, evaluations, information) must be correct, consistent with the genuine reality, verifiable and up to date. Obviously, this information must be exempt from bias, partiality, estimations subject to misinterpretation, elements which are expired or subject to “frequent” variations in space or time. In addition, the information provided must definitely be dated; and since perfection does not exist, the possibility of recourse in the case of errors or fraud is an indispensable counterpart to the credibility. Access to archived information for specific needs must also be made possible.

- – Requirement of generalization: to respect the conditions of healthy competition and equal opportunities, all products or services linked to a usage function, available on the market, old-established or about to be launched must benefit from the same information.

- – Requirement of economic acceptability: the global cost of the acquisition of enjoyment of such information must not detract from its accessibility for certain categories of consumers.

Nevertheless, that which is “free” outside of a commercial context is most often perceived as suspicious. Thus, the eventual cost of this information for the consumer must be linked to the potential reduction of the risks of bad choices, which are always too expensive.

Given such a set of requirements, it is not surprising that the current means of information are unsatisfactory and that a considerable number of choices are made by the decision-makers without having the relevant elements required.

Unfortunately, this also remains the case for product and design policies as well as during collective or individual product selection.

3.5.2. Proposal of product information systems8: dust removal method study

3.5.2.1. Information level 1: for uniquely descriptive information

- 1) General analysis of the usage factors and requirements for a family of products

This first step consists of:

- – an inventory of usage cases, in terms of user/commercial product/use environment relationships:

- – nature of floor coverings and furniture to be dusted,

- – size and particularities of the house: stairs, cupboards, ground floor, etc.,

- – type of dust and particles to remove: dog hair, bread crumbs, etc.,

- – aptitudes of some users: children, elderly people, etc.,

- – possible neighboring noise issues,

- – a long-term budget: “purchase price and actual costs of use”.

- – an inventory of the different types of competing products and collection of all the information concerning them (specific models, technical-commercial characteristics, standards, test specifications, comparative test results, etc.);

- – a qualitative study on the user’s requirements, the reasons for their dissatisfaction and the specific characteristics of their usage case.

NOTE.– A family of products is defined from a general-purpose function, for example: a domestic dust collection device, excluding technical functions.

Figure 3.9(a). Some competing products (more than 500 models)

Figure 3.9(b). More competing products (more than 500 models)

- 2) Creating a characteristic scale linked to usage for each specific type of product. This will include:

- – filtering the information available so that we only take in the characteristics relevant to usage. First, a work grid comprises the “union” of all future specific grids as well as all desirable characteristics, including those that are partially available (not all products are homogeneously described). Such a grid allows us to establish an “identity card” for any item of the family of products concerned;

- – choosing a category complete with an index (if necessary) to guarantee for all products comprehensibility and accuracy of the characteristics, the possible scalability to new headings and the homogeneity of the different grids of specific types of products that will result if necessary. In addition, it sets the vocabulary to be used in all of the following steps. To regulate the vocabulary, we must be able to fall back on a terminological reference (or thesaurus);

- – determining measurements or identifications concerning useful characteristics which are missing (conditions and measurement methods). For example, the action range of a device from a power outlet is relevant to the use, while the length of just the power cord is, without doubt, insufficient information;

- – using actual tests in order to outline any points of issue or to confirm certain “claims”. However, it is not a question of evaluating, even roughly, the general performances of the types of products.

- 3) Creating an information dossier on the descriptive characteristics of different types of products, as well as on all instructions related to usage. This information level does not cover any assessment of the performance of the products. Although the temptation is strong, the general assessments on the types of products from use surveys and/or pseudo-tests are to be avoided (see Volume 1 for information on the pitfalls of surveys and panels). However, this first approach constitutes an essential phase for the research of deeper and more systematic information.

3.5.2.2. Information level 2: for information on functional ability and safety

1) Critical analysis of the standards of functional ability and safety, in light of the remaining information and issues at level 1, and participation in standardized testing in accredited laboratories.

2) Adoption and/or suggestion of changes to standardized tests, or in the process of being, according to their relevance for use, and development of proper tests where they are lacking, with the help of standardization bodies, if possible.

3) Essential quality control tests, effective limits and the safety of the functional services provided by the products.

4) Technical safety tests exceeding, where necessary, the strict framework of the standards in force.

5) Possible extension of the information dossier with certain evaluations on the type of products, where a large number of items of each type have actually been tested.

6) Addition of qualitative sections and specific observations to the grids of the types of products as well as to the tested products’ files.

3.5.2.3. Information level 3: for more thorough information on the usage of items