Introduction

No healthcare facility exists in isolation; all provide essential services to their communities, and all are, in turn, reliant upon access to staffing, services, and materials with which to provide those services. In some cases, supplies may be locally sourced, while in others, essential equipment may have to come from the other side of the country, or even halfway around the world. In such circumstances, while the Emergency Manager may never actually be responsible for the creation and the operation of a healthcare facility’s supply chains, it is essential to understand how they work, how and why they are vulnerable, and how those vulnerabilities can potentially affect the facility. It is unreasonable to expect to be able to generate even contingency plans for a critical system, if one does not have a least a reasonable understanding of precisely how the system works.

In this chapter, the development, operation, and failures of healthcare facility supply chains will be examined. The operation of such chains and their vulnerability will be examined from a risk management perspective, along with the impact of such systems on the practice of emergency management, including their failure during an emergency. While the Emergency Manager is not a supply chain or logistics manager, it is essential to understand how such systems work, and also, to be able to identify how such systems may be employed during an emergency, in order to support the facility’s emergency operations.

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the student will have an understanding of how the supply chains which operate in healthcare facilities work. The student will be able to describe both internal and external supply chains. The student will be able to define the major supply categories for a healthcare facility, and to identify the source(s) for each category. The student will be able to identify the vulnerabilities of such supply chains, including both excess inventory and “just-in-time” inventory control, and the restrictions under which they operate, both inside the facility and externally, and also how they affect the day-to-day operations of the facility. While the student is not expected to be able to manage such supply chains, a sound knowledge of their operations is essential to the effective practice of emergency management within any healthcare facility.

Defining Supply Chains

A supply chain is a process whereby raw materials are transformed into usable products, warehoused, transported to market, purchased and delivered to consumers. In the case of a hospital, for example, this could be food, medications, single-use medical supplies, bed linens, or any of an entire list of “ingredients” which are essential to the patient care delivery process. Such processes are not typically owned in their entirety, but are held jointly by a variety of stakeholders, linked by contracts and other forms of service delivery agreements.

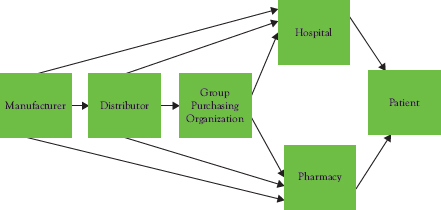

Such “chains” can lead from the local farm to the hospital, or they can reach around the entire world. Indeed, depending on the commodity in question, such chains can be tremendously long. To illustrate, in order to deliver a latex surgical glove to a hospital in Canada, the latex will need to be harvested by a farmer in Panama, sold to a wholesaler in the same country, who will arrange the shipment of the raw latex to a country in the Pacific Rim or to China, where it will be processed, fabricated into latex gloves, packaged, sterilized, and shipped once again, this time to a wholesaler, probably located in the United States. The wholesaler will arrange delivery to a regional distributor, probably in Canada, and that distributor will ship to order to individual hospitals and healthcare facilities. In contrast, a local farmer may have a contract to provide fresh agricultural produce to the local hospital’s dietary service. Both of these are somewhat simple descriptions of “supply chains,” (see Figure 3.1) but will suffice for the purposes of discussion.

Figure 3.1 Like most types of industries, healthcare facilities have their own supply chains

Every step in the process adds service provision costs, a level of profit margin, customs and excise charges, and perhaps sales tax to the cost of each commodity, and these can be increased further by transportation speeds, financing needs, and warehousing and storage costs. For the end user and most of the final distribution network for any given commodity, the only factors which can be controlled with any regularity are the cost of fast transportation, the need to warehouse the item in quantity, and the cost of having funds “tied up” by having paid for, received and stored merchandise which are not actually required yet. One of the key goals of supply chain management is to deliver such services using appropriate logistics, in a manner which eliminates stockpiling and keeps costs at the lowest levels possible, given the commodity. It has been said that “the supply chain is the network of organizations that are involved, through upstream and downstream linkages, in the different processes and activities that produce value in the form of products and services in the hands of the consumer.”1

Another concept which goes hand in hand with supply chain management is that of logistics. While not all of any given supply chain involves logistics, this concept does play a major role. It used to be commonly believed that logistics dealt largely with trucks and warehouses, but this is by no means accurate. Logistics is more about the absolute, consistent, and reliable control of the delivery process for a given commodity. It may be described as “getting, in the right way, the right product, in the right quantity and right quality, in the right place and the right time, for the right customer at the right cost.”2 Such concepts are essential to the understanding of supply chain management in a contemporary hospital or care facility. While they are essential to ensuring normal operations and ongoing service delivery in a responsible and cost-effective fashion, they will pose potential problems and challenges for the healthcare-based Emergency Manager during abnormal operations.

The Basics

In healthcare systems, the traditional mode of supply chain management has been “management by exception.” When applied to supply chains, this is essential a matter of maintaining large inventories and managing each shortfall as it occurs, using resources which are typically either on site or readily available. Such systems are old-fashioned, and, without doubt, expensive to maintain and operate. This was also true for industry, and for decades in the manufacturing sector, the role of managers was essentially one of fixing problems as they occurred and assigning blame for failure, where appropriate. Such processes are both expensive to maintain, and do not lend themselves to profitability. It is for this reason that the majority of large-scale manufacturing companies have moved away from such processes, primarily to reduce production costs and increase profitability. This movement was led by Toyota and eventually resulted in a process called “lean manufacturing” which has been immensely successful in the manufacturing sector.

Such systems embrace a process for continuous improvement, called PDSA (plan, do, study, analyze, or act)3, in which each operating system is examined in isolation, looking for methods of improvement, with a process broken down to its component parts, analyzed, an “improvement” tested, and if it works, formalized within the process. When a system or process does not work, the practitioner will employ Root Cause Analysis,4 a process which should already be a part of the Emergency Manager’s toolkit, in order to identify what is actually creating the problem, so that a solution can be implemented.

One manifestation of this process is known as “just-in-time” delivery, and has its basis in the manufacturing sector. In the automotive industry, for example, a given part which is required for the assembly of a new car may be manufactured a thousand miles or more from where the car is being assembled. Warehousing inventory costs money, and so the manufacturer attempts, wherever possible, to create each part only when it is needed, and deliver it just before it is required for installation in each new car which is being built. Given that this is a preplanned manufacturing process, it is entirely possible to accurately predict when each component will be required in the process, and to ensure that it arrives there on time. Any changes to the process occur far enough in advance that the system is rarely affected by any type of surge in demand, and can usually accommodate such surges.

“Lean for Healthcare” now commonly operates within healthcare settings, in North America and, increasingly, elsewhere. This version of the process uses most of the same tools as the industrial process, and particularly, those used for problem-solving.5 The challenge for the Emergency Manager is that, while the process creates many positive benefits for the day-to-day operations of any healthcare facility or patient care process, and is an invaluable long-term emergency planning tool, because of its relatively slow response times, it is particularly problematic and generates adverse effects, when its use in a currently occurring crisis response context is attempted.

For this reason, while such approaches to supply chain management by healthcare facilities can and do yield valuable cost savings and improvements to day-to-day services, they must also be understood and addressed by the Emergency Manager as a potential problems and vulnerabilities, requiring some levels of mitigation action, in order to ensure that they do not create problems when the facility is in “crisis mode.” This will involve understanding precisely how and why the existing supply chains work. As with most issues arising in a healthcare facility, there is generally someone, either on staff or under contract, who understands these issues intimately, and who can become a tremendous information resource and advisor to the Emergency Manager.

The Problem of Excess Inventories

Thirty or more years ago, most healthcare facilities possessed a large, internal inventory of mostly reusable equipment, and an internal service with which to manage its distribution, usually called the Central Supply Room or Supply Processing and Dispatch, or something similar. Here staff used and reused all manner of patient care equipment, including some items which would positively frighten and horrify the average reader who does not possess a clinical background. Few things were ever in short supply; however, vast amounts of operating budget were sometimes tied up in static inventory which “might be needed someday.” As technology changed, many items which were once reusable became single-use and disposable. In embracing best practice, and addressing considerations such as infection control, most facilities followed along with this trend. Unfortunately, the replacement of items which were used repeatedly with single-use technologies meant that the cost of most types of patient care supplies actually rose. While multiuse items cost more, single-use couldn’t be used repeatedly, and so the lower purchase price translated to a higher overall cost for hospitals.

Higher cost, often customized items, such as surgical instrumentation and medical electronics continued to be reusable, but the supplies of these items were limited to an amount which might be normally required. To illustrate, most hospitals do not generally have excess amounts of typically expensive surgical instruments. Hospitals have more or less the quantity of surgical instruments which they would normally use in a given day, and rely on these being cleaned, resterilized, and reprocessed, usually overnight, for use the next day! In the case of a mass casualty incident generating large numbers of patients requiring surgery, the biggest single challenge may be to reprocess surgical instrumentation quickly enough to keep up with the demands of the surgeons!

The other challenge with such supply arrangements was the amount of space typically required in which to securely store and reprocess large amounts of inventory for all manner of patient care items. One of the biggest challenges faced by most hospitals is the ability to provide sufficient operating space for competing specialty services to operate in. The competition for literally every inch of underused space is normally quite intense. In addition, many administrators looked at the costs of heating, lighting, and staffing such underused storage spaces, and the potential for freeing up both space and operating budget to provide improved services was evident. This pushed many healthcare facilities, of all types, to move toward some form of logistical process, such as “just-in-time” delivery of most items used on a consistent basis.

The Problem With “Just-In-Time”

Healthcare technology has changed, however, and now, almost everything used, with the exception of surgical instrumentation, is single-use, and is now created in distant countries at much lower cost.6 Even with the savings generated by these changes, such systems are not cheap. As a result, limited numbers of each item are kept on hand, attempts are made to accurately predict the usage of such items, and the facility is subject to the effects in any surge in the predicted demand. Such logistical arrangements have become so formalized that, at this point, the vast majority of inventory is not in cupboards or other fixed storage; it is literally on wheels!

In healthcare, virtually everything which is in use, with the exception of surgical instrumentation and medical electronics, are often subject to such a system. This includes all food, most medications, single-use medical supplies, intravenous solutions, bed linens, and even staff! Analysis of usage has occurred, and carts containing only what is actually required for normal use, with a small buffer for overages, is provided in each service delivery area. In most cases, just around the time that a given item is running out, the cart will be replaced with a fully stocked new cart, and the old one removed and resupplied, prior to being returned to the rotation cycle. Such logistics-based management works fine on a daily basis within a healthcare facility. However, such systems are subject to a number of issues which are only partially amenable to such planning, and some which cannot be predicted at all. These include the human factor; both patients and staff, and also the transportation networks which are used to deliver requirements.

There is a reason why healthcare facilities staff on a 24-hour basis; services are being provided to human beings who are, by their very nature, unpredictable. Anyone attempting to suggest to a major hospital, for example, that they don’t need to ensure that medical specialty services are available 24 hours per day would be laughed out of the meeting. The factors which create human needs for healthcare services are immensely complex, and only some of them are even amenable to predictive modeling. While the daily parade of walking wounded and worried well through an emergency department may be somewhat predictable and manageable, the airplane crash which throws the entire daily system into chaos is not. Nor is the snowstorm which blocks all deliveries to an isolated community hospital for a week, or a labor disruption. This is why hospitals and other healthcare facilities NEED Emergency Response Plans; because “business as usual” is not always feasible in such settings!

Any hospital can quickly go from a predictable workflow with a weekly delivery of essential equipment required for care, to a massive surge in demand for services, in which two weeks’ worth of a given item (e.g., I.V. tubing or oxygen masks) are required in a single afternoon! To make matters even more complicated, most of those businesses which supply healthcare facilities with their needs also operate on some form of “just-in-time” and, as a result, there is rarely sufficient surplus in the system with which to buffer surges in demand. In summary, while “justin-time” can be an effective method for the daily management of both equipment and resources, it is not particularly effective at the management of “just-in-case”!

The entire process of “just-in-time” delivery has been exported wholesale from the manufacturing industry, where demand is continuous and wholly predictable, and where it matters far less if supply chains are briefly interrupted and services must be curtailed. In manufacturing, the cost of such an event is in dollars, whereas in healthcare, the disruption of services can literally cost lives. In order to be able to create an adequate and effective Emergency Response Plan, there are fundamental questions to which the Emergency Manager MUST have answers!

What Is the Item/Service?

No two healthcare facilities are exactly alike. There is a vast list of items that are required in order for a healthcare facility to operate effectively. Not all facilities use the same items and services, and these variations will be driven, to some extent, by the core business of the facility. They will also be driven by the regional availability of products and services, the organizational culture, and the outcomes of bidding/purchasing processes. Some variations will also be the result of geographical differences and even isolation (see Figure 3.2). These may include, but is by no means limited to:

Figure 3.2 Common healthcare facility logistical requirements

This list is generic, and by no means, exhaustive. Every healthcare facility is unique, and the Emergency Manager MUST possess a comprehensive understanding of precisely what is needed, and how the requirements of their facility may differ from those of other facilities. Create a list, talk to department heads, talk to individual staff members. The information required already exists, the Emergency Manager simply needs to be able to find it! It may be useful for the Emergency Manager to generate a profile for each individual resource on a single sheet of paper. Ultimately, such information should find itself in the hands of whoever is responsible for the Logistics function in the Command Center. It may start out as individual profiles, and then progress from there to a binder (a backup function) and also to a proper, searchable database on Command Center computers.

Where Does This Resource Come From?

In order to ensure a viable Logistics function, the Emergency Manager must understand all supply chains, at least in the latter stages. No vital resource is of any use to a facility if it cannot be accessed. The nature of the supply chain will be determined, to some extent, by the physical location of the facility. Large, urban facilities tend to have short supply chains, as local distributors tend to congregate closer to their largest customers. Isolated and rural facilities tend to have supply chains which are longer and more vulnerable.

To illustrate, a large snowstorm, or localized flooding, may delay normal deliveries in a large urban center, but 24-hour access to suppliers can be negotiated, and expedited delivery services are available, if required. With rural and isolated hospitals, if the same event closes the single road in and out of the community, it can take days to access required supplies, and 24-hour access is probably irrelevant. Interestingly, rural and isolated hospitals tend to be more aware of their situations, and, after a few risk exposures following the adoption of “just-in-time,” many began to quietly develop their own backup inventory stockpiles, and many can last a week or more beyond the anticipated regular deliveries, in many respects.

Such vulnerabilities can be driven by local, regional, or even international events. A wildland fire, severe weather, or a transportation incident may close the single local road or rail line upon which essential deliveries travel. A severe ice storm, such as that which occurred in the Eastern United States and Canada in 1998, can result in regional transportation paralysis for days or even weeks,7 This type of event can also provide for severe utility disruptions, particularly for services which are conducted above ground, such as electricity and telecommunications. On an international level, following the events of 9/11, the United States closed its borders, and literally ALL Canadian healthcare facilities were forced to conserve or re-source a great many of their essential supplies, since these are normally provided through the United States. The new, post-9/11 realities are that borders are becoming increasingly difficult to cross, both for people and for goods,8 and the reality of what occurred immediately post-9/11 could become an occasionally recurring event for Canadian hospitals and other healthcare providers. There has also been considerable speculation regarding access to personal protective equipment (PPE) and isolation supplies with respect to the planning for any pandemic involving influenza or a similar disease outbreak, as this would result in a massive surge in demand worldwide, and current supply chain arrangements are not configured to cope with such surges.

As another example, the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 produced a worldwide shortage of PPE for healthcare workers and even mechanical patient ventilators, and made finding decent quality surgical masks difficult for hospitals in various countries. Eventually, companies around the world began manufacturing PPE and ventilators, having never done so before, and airlifting them across continents to the highest bidders.

How Does This Resource Get Here?

It is essential to understand how goods and services reach the facility, if the Emergency Manager is to identify and understand the vulnerability exposures which may be present in the supply chain. The lengths of supply chains, the methods of delivery, and environmental concerns all have the potential to be affected by adverse events. If by road, are there alternate routes which are readily available? If by rail, can the goods or services be moved alternatively by road? Is the facility so isolated that supplies must be flown in, and how often do adverse weather conditions occur? Through understanding the modes of transportation for each resource, the ability of the Emergency Manager to identify and to understand potential vulnerabilities which may be inherent in the supply chain are enhanced. While it may not be possible to mitigate against all such vulnerabilities, they will, at least, not come as a complete surprise if they occur.

How Important Is This Resource?

For the development of an effective Logistics section for the facility’s Emergency Response Plan, the Emergency Manager must have a more detailed understanding of each resource, and how it is used. How many units of a given resource or service are normally kept on hand in the facility? How long does it normally take to obtain a re-supply of this resource? What are the impacts of the lack of availability for a given resource or service? How long can the facility manage to continue to operate normally and provide normal services without the resource? How frequently is the resource in question used/needed? Does its absence result in an inconvenience, a postponement of service delivery, or a loss of life? The answers to these questions will help to set planning priorities, and they may help to develop mitigation strategies for alternative supplies and “work-arounds,” for incorporation into the Emergency Response Plan. At a minimum, the answering of the above questions will help to both identify and quantify potential risk exposures by the Emergency Manager.

Are There Vulnerabilities in the Supply Chain?

The good news is that, if the Emergency Manager has completed the Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment process for the facility,9 it is highly likely that most of the information required in order to answer this question has already been generated. Recall that the risk exposures for a typical healthcare facility will fall into one of three categories; internal hazards which disrupt business operations, internal hazards which can affect building or facility operations, and external hazards which can generate or disrupt business. This latter category deals with external risks, and it will provide a clear indicator of what is physically possible within the region in which the healthcare facility is situated. These same events will also occur for those operating the supply chains and the associated logistics.

While some logistical services may experience little or no impact, or differing impacts that the healthcare facility, the Emergency Manager will at least understand which impacts they are subject to, and what the results of occurrence are likely to be. To illustrate, the ability to repair a portable defibrillator which has to be transported 50 miles (80 km) by road to be repaired is much more likely to be vulnerable to a severe winter storm than food delivery, when the delivery occurs weekly, and the last occurrence was two days ago. In the former case, the potential outcome is the longer-term loss of an essential device which could result in loss of life, while in the latter case, there is a sufficient reserve to cover the entire period in which transportation is likely to be affected.

The use of the data generated by the HIRA is essential; it identifies not only potential problems, but also the relative probability of their occur-rence. The information is research based, and it can be used to support arguments in favor of mitigation efforts. Most importantly, the process involved is based upon fact, and upon real experiences, not guesswork. The ranking system used in this process also provides a realistic and objective evaluation of which types of scenarios actually NEED to be planning and mitigation priorities, and which do not.

In What Types of Scenarios Are Your Supply

Chains Vulnerable?

For the average Emergency Manager, the answer to this question will be based largely upon two separate and distinct sets of information. The first of these involves the nature of the supply chain in question. In this case, the Emergency Manager should probably focus on the nature of each type of supply chain. Remember, all healthcare facilities are supplied by multiple sources, each with its own specific logistics arrangements. For the purposes of emergency planning, the point of focus within the supply chain should probably be from the lowest tier supplier to the doors of the facility. Beyond this, vulnerabilities are still possible, but are largely beyond the scope of practice of the Emergency Manager, and beyond any ability to mitigate, in any case.

It has been said that risk and vulnerability are not universal, nor are they equitably distributed. In order to understand inherent vulnerabilities, research must be conducted, and risk exposures must be studied. There are inherent vulnerabilities in most types of transportation and logistics networks. The technology used may generate some levels of risk exposure. To illustrate, aircraft do crash occasionally, ships sink, trains derail, and heavy trucks have accidents. Most operate within specific corridors of infrastructure, and that infrastructure can, in and of itself, generate some types of vulnerability. This is particularly true when the capacity infrastructure is severely limited and/or becomes damaged. In this case, consider the impacts of severe weather on heavy trucks and their delivery schedules. Similarly, there are regions in the world which continue to be served by single track train services. When any type of accident occurs, or when the railroad elements require replacement, this too can slow the flow of logistics to the point at which alternative delivery arrangements, if these are available, must be made.

The second question involves the facility’s physical location, including distance from the supplier. Is either end of the delivery route, including the supplier, the route itself, and the receiving facility, located in any area which contains specific risk factors? These include physical terrain, including mountains, plains, floodplains, and rivers. Also requiring consideration are the characteristics of the environment between the supplier and the facility. What weather conditions occur regularly within that environment, and what problems have occurred in the past?

It is equally important to examine the security of the infrastructure of both the supplier and the receiver. In an earthquake zone, for example, the supplier, the facility, or critical infrastructure such as roads and bridges, may be affected by the primary effects of the earthquake, or by the liquefaction of the ground upon which they are located. Some problems are inherent in certain environments, while others are simply impossible. Once again, the research conducted as a part of the HIRA process will contribute greatly to the understanding of these issues. Students are recommended to review the HIRA of the American city of Seattle, whose HIRA document is one of the best that the author has ever seen.10

How Do Vulnerabilities Occur?

No system supplying healthcare facilities is ever completely foolproof, regardless of efforts to the contrary. Virtually all supply chains are vulnerable, including those which serve healthcare facilities. It can be said that contemporary supply chains tend to focus on efficiency, rather than effectiveness.11 No human endeavor is perfect, and there are a number of common areas of vulnerability, including:

Natural Hazards—Severe weather of all types, geological hazards, such as earthquake, landslide, and subsidence, and any type of flooding which directly affect the transportation infrastructure, including roads, bridges, tunnels, and rail networks.

Accidents—The operators of delivery vehicles may be careless, or they may be affected by the carelessness of other users of the road. This is particularly problematic in circumstances where there is only a single route to the destination available. Essential shipments may be delayed, or even destroyed.

Terrorism—Deliberate acts which damage or destroy road and rail infrastructure, or which greatly delay shipments, particularly those of an international nature.

Strikes and Protests—A prolonged strike by unionized truckers, long-shoremen, or a (see Figure 3.3) railway’s employees may render supply chains useless,12 as may a scenario in which a strike occurs at a healthcare facility, and unionized truckers refuse to cross picket lines to make deliveries. While strikers are not as likely to disrupt ambulances (and therefore, patients) entering hospitals because it erodes public support for their cause, the same concern is not typically extended to the trucks carrying the items required to feed or care for those patients.

Figure 3.3 During the London Underground bombings, area hospitals had to deal with a mass-casualty incident while transport and re-supply routes were closed

The System Itself—This may sound strange to the reader, but its true. While the manufacturing and retail sectors have developed impressive supply chain systems, the situation in healthcare continues to be different. In many hospitals, front-line staff continue to struggle and spend far too much time hunting for a single piece of equipment, often in the midst of rows of equipment carts; the item is there … but actually finding it at the point of use is often problematic. Moreover, many healthcare facilities currently form regional purchasing consortiums, aimed at obtaining the best prices possible for everything that they use.13 This practice achieves savings, but often leads directly to very limited “buffering” to support the “just-in-time” system (see Figure 3.4) in emergencies.

Telecommunications Failures—This is generally a short-term problem, but it can affect the urgent requirements of some healthcare facilities. To illustrate, a critical patient urgently requires a particular blood type, none of which is on hand, and the telephone network is down. Not all supply chains are long, but all can be vulnerable in the right circumstances. To illustrate, following the London Underground bombings, emergency service workers, who had become dependent upon the public mobile telephone network, found that communications networks were overloaded, and that critical contacts could not be made.14

Figure 3.4 The adoption of “just-in-time” along the entire supply chain reduces resiliency

Limited Inventories at Point of Use—The more of a given resource that is kept on hand, the less the effects of any type of delivery disruption. The “just-in-time” philosophy of supply chain management essentially saves money by minimizing on-site inventory and hoping that no disruption of the supply chain will occur. This approach can save money and space within a healthcare facility over the short term, but it is always a gamble. This planned lack of resiliency can also significantly increase a facility’s vulnerability to any problem which may occur, anywhere along a given supply chain.

What makes it even more complicated, is the fact that most of the “middlemen” (wholesalers and distributors) along any given supply chain are also practising “just-in-time” to reduce warehousing costs. While a facility may have been told by a wholesaler that a reserve supply of inventory is maintained in case of emergencies, it is essential to ask further questions, and discover exactly what that means. In many cases, the wholesaler will have warehoused enough of a given resource to re-supply a given hospital in an emergency situation, but, in fact, supplies fifty or more hospitals! As a result, there is rarely as much of a “buffer” in the system for use in addressing emergencies, as many administrators and those who advocate these practices would like to believe. The first region-wide emergency is likely to make the realities of this practice painfully apparent.

Globalization—The world has become an increasingly competitive global marketplace which strives to maximize the wealth generated by a production capability. To illustrate, the majority the production of single-use medical supplies now resides in both China and elsewhere in the Pacific Rim,15 and serves medical community of the entire world. This measure has occurred over the past 20 years, in order to reduce production costs and increase profitability (see Figure 3.5).

In periods of shortage, it may be that limited availability will drive up prices, with a result of either increasing a healthcare facility’s operating costs, or of decreasing availability of the item. In such cases, those willing to pay premium prices for a commodity will receive priority of supply, while those who cannot afford to do so may receive none at all. It may also be that a single facility which has been more forward thinking and has predicted a need and simply purchased all of a given resource that is available within a region. This has the potential to become a particularly serious in a pandemic scenario.

Figure 3.5 Increasingly both medical devices and drugs actually come from distant locations

Transport Resource Availability—Essential deliveries may be affected by extreme fuel shortages, the lack of availability of transport vehicles or repair parts due to mechanical failure, or a shortage of vehicle operators. It must be borne in mind that such deliveries or resources within healthcare utilize a transportation system which is primarily designed and operated to address the needs of the much larger manufacturing and retail sectors, in which delays in delivery can be anticipated and worked around, because they are generally less time sensitive than those of hospitals. Moreover, in the logistics sector, a truck is a truck and a load is a load, and in times of availability shortages, hospitals will have to compete for access with manufacturing and retail firms with extremely deep pockets.

The Benchmarks

It is insufficient for the Emergency Manager to understand how the supply chains and their associated vulnerabilities operate. In order to be able to create a truly effective emergency Logistics function, the Emergency Manager must also possess a detailed understanding of the internal supply arrangement of the facility itself. This will include understanding the normal quantities of essential resources which are normally kept on hand, the threshold for re-supply, and how those re-supply arrangements normally operate. Logically, one must understand what is normal with a given situation, before one can begin to effectively perform contingency planning in order to address the abnormal.

Identify the Resources Needed—A typical healthcare facility uses literally a mountain of different materials, products, and services. Some of these are essential, and some are not. In order to develop an effective emergency Logistics section for the Emergency Response Plan, it is necessary to understand precisely what items are on that comprehensive list, as well as which of these are actually essential, and why. This will involve a dialogue of some sort with those who actually responsible for each resource on a daily basis, since they will understand the resource, and its use, far better than anyone else in the organization.

Develop Resource Profiles—In order to create a standardized process, it may be possible for the Emergency Manager to develop a relatively simple but comprehensive “profile” for every item which falls into the essential category. There is little point to the Emergency Manager planning contingencies for resources which are “nice to have,” but not “need to have.” Such a profile can be used to develop a reference source for the Logistics Lead in the Command Center during a crisis. Such profiles can be placed within an alphabetized binder, for use as a reference resource within the Command Center.

In a more elaborate form, they may also be used by the Emergency Manager to create a formal database, using software such as Microsoft Access,16 for use in the Command Center. Virtually every healthcare facility uses databases, and it is best to employ the same software that is in everyday use, as this will ensure that support is readily available. If the Emergency Manager lacks the skillset to create the database, virtually every healthcare facility has at least one “expert” user, and this individual could easily become the Emergency Manager’s ally, and perhaps, an expertise resource to support the Command Center during a crisis. Even when the database approach is employed, it is prudent to also develop and maintain the alphabetized binder, as a “backup” strategy for use during computer and network failures.

What Is the Resource?—Describe the resource, using language that anyone will understand. Be specific in your description. Specify what the resource used for, both normally and during emergencies, if the uses are different. If the facility uses an inventory number for the product, specify this for the purpose of clarity. If it is available in different sizes, specify these. Is this a frequently used item (e.g., I.V. tubing sets), or an infrequently used item (e.g., triage tags)?

How Many of This Resource Do We Normally Keep on Hand?—Whoever is responsible for inventory control within the facility should be able to provide approximate counts of any item which is normally kept on site. This individual is also a logical choice to help with the completion of at least some of the profile development.

How Many of This Resource Do We Normally Use in a Week?—This information, when compared with the information regarding amounts kept on hand, will provide insight into the amount of “buffer” that is normally available within the system for increased usage during emergencies. With the Planning function monitoring usage of the resource, the time to loss of the resource and the need for emergency re-supply should become apparent. This information regarding the difference between “normal” consumption and current consumption may prove invaluable, and the longer the facility’s supply chains, the more invaluable that information becomes.

Is There Competing Demand for Existing Supplies?—Attempt to determine whether sufficient quantities of the resource are available, both on hand and through the primary and secondary distributors. Would competition for resources occur during a purely local emergency? Would a regional emergency result in a shortage, and, if so, how long would it take to fill the need? Would a truly large event, such as a pandemic, result in a shortage of the resource, or even complete loss of access? This is essential information to have for planning purposes. In 2003, the Sudden Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Toronto, Canada resulted in shortfalls in availability of PPE for nursing personnel, an absence of adequate existing isolation care spaces with the hospital network, and even a shortage of personnel to test and monitor the nurses for exposure. In the Toronto outbreak, 45 percent of all cases of SARS were among healthcare workers, while in Taiwan, 160 physicians and nurses refused to work because the available PPE was inadequate.

Indeed, it is appropriate to view staff as a resource or commodity and a planning priority, as well. During the same incident, care personnel, including physicians, nurses, and paramedics, were in such short supply that staff who were exposed, and who should have been in quarantine, were ordered to continue to work in PPE. In most cases, existing PPE was inadequate, and better equipment was in extremely short supply, and staff suffered as a direct result.

Who Is Responsible for This Resource?—In all cases, it is useful to identify the individual who is responsible for every resource being profiled. This is likely to be the person who knows the most about the resource in question. Information should include the original source of this resource, along with its normal use and consumption patterns. They are also likely to be the most aware of any problems associated with its use, including such key information as safety restrictions and potential for dangerous interactions. This individual is also likely to be able to describe the types of quantities normally kept on hand, alternate replacement sources, and replacement timespans.

In some cases, there may be issues related to the security of a given facility operation and the disclosure of this information, even to the Emergency Manager. Obvious locations which might fall into this category would include the pharmacy, hospital laboratories, or nuclear medicine services. In these cases, the person primarily responsible for the operation in question should be directed to complete their own binder and/or database, using precisely the same model as the mainstream tool, and advised that the information contained must be made readily available to the Command Center during any type of crisis operation. This approach keeps sensitive information secure on a daily basis, while ensuring its availability, if required during any emergency.

Where Do We Keep This Resource?—In each case, determine where the resource in question normally physically located. If it is normally in multiple locations, list all of them. Is the storage location secure? If so, it is prudent to create instructions for afterhours access, including the names of contact persons, the location of keys, and so on. Any resource which cannot be readily accessed is not readily available. Access arrangements must be formalized and documented in advance. The individual setting up and running the emergency response at 2 a.m. has even less knowledge about how things work and where to find things than the Emergency Manager, and the middle of a crisis is not the time to begin a new learning process.

Contingencies

Once the Emergency Manager has fully documented the resources available on-site and how to appropriately access these, it is time to consider how to address those resources which are not readily available. Those abnormal use issues which are generated by a facility’s “just-in-time” approach to logistics management may be addressed by using a variety of potential strategies. The practicality and application of each of these strategies will vary according to the institution and its corporate “culture,” budget, location, and resource availability.

Rotating Inventories—One of the easiest contingency solutions to arrange is the concept of rotating inventories. Using this model, all of those items which might experience urgent surges in usage during an emergency are identified in advance. A “rotating” inventory pool is then created, in which there exists a one-time purchase of sufficient inventory with which to manage a large emergency (size must be predefined), outside of the normal “just-in-time” purchasing arrangements. This stock is then placed within the appropriate storage locations in Supply Processing and Dispatch. As items are required for daily use, they are drawn from this stock, which is continually resupplied, using the existing “just-in-time” purchasing and delivery arrangements.

As a variation on this contingency model, those facilities which use a system of prestocked supply carts have the potential to create a “buffer” of one or two times the normal number and types of supply carts on-site. The carts receive their regular replacement in the various service units by rotation, with the logistics company adding carts to the back end of the queue, and collecting those carts which have been used for inventorying and restocking. In this manner, the facility can readily accommodate a surge in service demand of two to three times its normal volume, while maintaining the economic benefits of “just-in-time”!

There are, of course, negatives to this approach, and the first of these is the cost of the additional supplies and carts, but these are one-time costs, and probably justifiable, in terms of emergency preparedness. The second challenge is space usage. While a standard rotating inventory would normally occupy a single large room, the space required to store so many supply carts might be more difficult to find. This is particularly true, given that either model is going to require secure storage, since “shrinkage” will undoubtedly occur, otherwise.

Twenty-Four Hour Access to Suppliers—This type of access should be stipulated in absolutely every Emergency Response Plan for a healthcare facility. Surprisingly, it remains somewhat uncommon in many jurisdictions. In talking to those who make their living supplying healthcare facilities with goods and services, they too are quite surprised that this request comes up as infrequently as it does, given that most manufacturers and services providers have mandated this in their supply contracts for at least a decade, and frequently two decades.

Every Emergency Manager working in healthcare should be lobbying for 24-hour emergency access to be mandated in every new service, supply, or equipment contract entered into by their facility. This requirement should include the provision of emergency access numbers which are answered by suppliers around the clock, and should specify the amount of the resource which is available in an emergency order, and how long such an order will require to be filled and delivered. In the Purchasing and Finance departments of healthcare facilities around the world, a great deal of time has been spent on the inclusion of “just-in-time” arrangements in healthcare supply chains and logistics arrangements. Who better than the Emergency Manager to champion the cause of equal attention being paid to contract clauses which appropriately address “just-in-case”!

How Long Does It Take to Get More?—This is an extremely valid question for planning purposes. Even when a resource is available for emergency re-supply, it will often take time for that re-supply to occur. This is particularly true as the supply chain lengthens, and as the distance between supplier and end-user increases. Small, isolated, and rural hospitals have long been aware of this reality, and many have a history of quietly “caching” emergency supplies, and practising rotating inventory arrangements, even when they were not encouraged to do so. A small hospital, often 200 miles (320 km) from a major center, knows exactly how long, and how vulnerable, the final link in their supply chain is. It can be affected by weather, and by all of those things which make reliance on a single road or transportation system a gamble. Moreover, they may not have the resources to pay for more expedited delivery (e.g., air) or it may simply be unavailable. Given that a typical major medical emergency can take six to eight hours to resolve, at least, at the front end, if it takes two hours to recall staff outside of business hours, another two hours to process the emergency order, and then a four-hour truck trip to make the delivery, the time required to achieve an actual emergency delivery from a supplier can be absolutely critical information, and may help to drive decisions on precisely what advance contingency arrangements are needed. This problem only increases with physical distance and geographical isolation. If the small hospitals of the isolated hinterlands of North America are this vulnerable, what does this say about those located in small island nations, or in communities in the developing world?

What Is the Threshold for Emergency Re-supply?—Given the circumstances and the realities just described, advance decisions regarding local inventory levels and re-supply arrangements are absolutely essential in healthcare, wherever it is conducted. Thus the “threshold” for re-supply should be driven by three questions:

1. How many individual units of a given resource are we likely to need to in order to effectively manage this particular incident?

2. How many individual units of this particular resource do we currently have on hand?

3. In the current conditions, how long will it normally take for an emergency service or resource delivery to reach us?

The answers to these three questions can and should drive the development of a threshold for decision on when to place an emergency re-supply order. The questions and the methodology remain the same, whether the hospital is large or small, and whether it is located in a large urban center, or on a small isolated island. The pursuit of such thresholds should be a part of the Emergency Manager’s agenda, and it should be pursued through inclusion in briefings to the senior management of the facility, emergency exercises, and in the reporting of results of those exercises.

Are There Alternative Sources/Workarounds?—There will undoubtedly be occasions in which current supply and resource levels are inadequate, and in which those levels cannot be readily or easily enhanced, despite the best efforts of the Emergency Manager and all concerned. In such cases, creativity will clearly be required by all concerned, if the response to the emergency is to be successful. This may involve the accessing of alternative sources for the resources which are required to run the facility, whether these be competitors of primary suppliers and unsuccessful bidders, or it may be local businesses which do not normally interact with the hospital in a business sense, but who might be called upon to assist in an emergency situation. Each of these will have to be considered, along with their potential contributions, during the advance planning process.

To illustrate, if an isolated hospital in a small community experiences a severe winter storm on the day that its scheduled weekly delivery of food is to occur, that delivery might not be possible for two or three days, depending upon the location and the amount of road clearance that is required. The hospital may have a small buffer of some food items, but is more likely to experience problems, particularly if the “house” is full! That being said, most public sector Emergency Managers operate with a planning assumption that most communities, regardless of size or location, usually have a sufficient quantity of both food and fuel within them to last for at least seven days. This is true whether the sources are a massive food warehouse and distribution center and a fuel tank “farm,” or a small, local supermarket, and a single service station. In such cases, it would be entirely reasonable and prudent to negotiate an advance agreement with the owner of the grocery store to provide the hospital with food until deliveries for both can be achieved. A similar arrangement might also be possible for some, but not all, items, with a local retail pharmacy, remembering, of course, that hospital pharmacies and retail pharmacies often have somewhat different inventories. Similarly, if the primary supplier of oxygen masks cannot deliver an emergency supply of replacement equipment, it is perfectly reasonable to call up the primary supplier’s competitor, often an unsuccessful bidder themselves, and ask them if they can help. The same can be true for most other single-use medical equipment, as well as bed linens.

Another option is the potential use of “work-arounds,” or improvisations in service delivery from normal practices. Consider, once again, a severe winter storm occurring in a small town. This storm has made roads impassable, and the hospital is experiencing problems with staff who are unable to get to work for their scheduled shifts. It may be possible to develop an emergency support agreement with the local snowmobile club to transport staff members to and from work, until the roads can be reopened. There are precedents for such arrangements within healthcare. Many hospitals in several parts of the world have developed emergency relationships with amateur radio operators and their clubs, to provide a communication “work-around” in the event of telephone failure.17 In the Canadian cities of Ottawa and Toronto, local healthcare providers have developed separate private twoway radio networks, in the case of Ottawa called the Hospital Emergency Radio Network of Ottawa, to permit communication among themselves in the event of any telephone network failure.

All such arrangements are best negotiated and agreed upon in advance by all of the parties concerned, if they are to be of assistance to local healthcare during a crisis. There are two old adages among Emergency Managers which come to mind here. The first is that “just because something exists in your community doesn’t guarantee that you can simply have it during a crisis.” The second is that “the best time for the hospital to meet the Fire Chief is NOT when the hospital is actually on fire!” There is a wisdom in these two sayings that is drawn from years of experience.

Conclusion

No healthcare facility, anywhere in the world, exists in a vacuum. All are an integral part of some type of community, and, it can be argued that healthcare facilities are, for all practical purposes, simply small but specialized communities. In addition, these “communities” tend to house and support what can probably be argued to be the largest population of truly vulnerable persons within the entire community in which they are located. Communities are all dependent on various supply chain arrangements for most of the goods and services which are required in order to sustain them, and, as communities, healthcare facilities are really no different. The goods and services may differ somewhat from those used in the larger community, but the concept is precisely the same. And just as the communities which they serve, healthcare facilities are equally both dependent upon supply chains and vulnerable to their failures.

While supply chain management is not normally considered to be a part of emergency management, as has been stated repeatedly, the good Emergency Manager is not a specialist, but rather, a sophisticated generalist. While the Emergency Manager will never really be expected to operate supply chains, their functions, vagaries, and failures can clearly either support or disrupt the emergency management process, whether occurring in a community, or in a healthcare facility. As such, being subject to supply chains and logistics, the Emergency Manager operating in a healthcare setting must, at a minimum, understand them and how they both impact on the facility and affect the practice of emergency management. They represent too great a potential impact on the emergency management process to be ignored. One cannot plan effectively for any issue which one does not understand.

Student Projects

Student Project No. 1

Select a local hospital. Consult with the hospital Pharmacist and identify and map the normal supply arrangements and supply chain for pharmaceuticals for that facility. Now conduct the appropriate research and identify three scenarios involving external hazards, in which the pharmaceutical supply chain of the hospital might be compromised. Create a report outlining your findings, explaining the rationale for each, and recommending mitigation strategies. Ensure that the report is appropriately referenced and cited, in order to demonstrate that the appropriate level of research has occurred.

Student Project No. 2

Select a local healthcare facility. Consult with your local Office of Emergency Management (or equivalent) and identify known infrastructure vulnerabilities within the community. Now identify an incident from among those in the local HIRA and conduct the appropriate research. Create a report explaining how the occurrence of this event might disrupt the facility’s ability to maintain normal staffing patterns and provide care to increased populations. Ensure that the report is appropriately referenced and cited, in order to demonstrate that the appropriate level of research has occurred.

Test Your Knowledge

Take your time. Read each question carefully, and select the MOST CORRECT answer for each. The correct answers appear at the end of the section. If you score less than 80 percent (8 correct answers) you should reread this chapter.

1. In a contemporary hospital, items which are subject to the use of supply chains in order to ensure delivery include:

(a) Food

(b) Medications

(c) Bed linens

(d) All of the above

2. A supply chain deals with the process of acquiring and moving a given commodity from its point of creation to the:

(a) Manufacturing process

(b) Warehouse

(c) End-user

(d) Distributor

3. In a healthcare setting, logistics deals with the delivery of:

(a) Products

(b) Services

(c) Knowledge and information

(d) Both A and B

4. While “just-in-time” delivery provides a valuable benefit to healthcare facilities by reducing the costs and problems associated with normal use, it can present:

(a) Significant problems during an emergency

(b) Problems of excess inventory

(c) Increased staffing requirements

(d) All of the above

5. When assessing the vulnerability of a healthcare facility’s supply chains, it is essential for the Emergency Manager to specifically study both infrastructure elements of the supply chain and:

(a) The Environment

(b) Levels of Emergency Preparedness

(c) The Supplier’s Business Continuity Plan

(d) All of the above

6. When a healthcare facility requires an emergency re-supply shipment, the biggest factors which can adversely affect a rapid delivery of resources are the distance from the supplier, and:

(a) Purchasing Procedures

(b) Travel Conditions

(c) Shipping Costs

(d) Approval Processes

7. The most effective method of expediting emergency re-supply decisions during any crisis is to:

(a) Maintain a Direct Line to Purchasing

(b) Contact Suppliers Before the Emergency Begins

(c) Create “Thresholds” for the Re-supply of Resources

(d) Both A and B

8. Once the Emergency Manager has identified a potential “work-around” for an essential resource or service, for use during any crisis, the most important measure is to:

(a) Negotiate an Agreement for its Use

(b) Secure it’s Use Through a Purchase Order

(c) Conduct Police Background Checks

(d) Both B and C

9. One of the simplest and most practical methods for the Emergency Manager to create increased capacity to address surges in demand for service with a “just-in-time” inventory management system is through:

(a) Persuading the Abandonment of “Just-In-Time” Inventory Control

(b) Creating a “Rotating Buffer” of Essential Resources

(c) Increasing Weekly “Just-In-Time” orders by Ten Percent

(d) Scheduling Surges to Coincide with Deliveries

10. In circumstances in which some Department Heads might be reluctant to provide supply information to the Emergency Manager’s Emergency Logistics Database for reasons of security, an appropriate response is to:

(a) Direct the Creation of a Parallel Confidential Database for that Service

(b) Ensure That the Information Will Be Accessible During a Crisis

(c) Ask the CEO to Order the Release of the Information

(d) Both A and B

Answers

1. (d) 2. (c) 3. (d) 4. (a) 5. (a)

6. (b) 7. (c) 8. (a) 9. (b) 10. (d)

Additional Reading

The author recommends the following exceptionally good titles as supplemental readings, which will help to enhance the student’s knowledge of those topics covered in this chapter:

Mangan, J., C. Lalwali, and T. Butcher. 2008. Global Logistics and Supply Chain Management. Chichester, UK: Wiley & Sons.

Wolper, L. 2003. Healthcare Administration: Planning, Implementing, and Managing Organized Delivery Systems. Lanham, MD: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Seattle OEM. 2014. “SHIVA—The Seattle Hazard Identification and Vulnerability Analysis.” City of Seattle, Office of Emergency Management.pdf document, www.seattle.gov/emergency (accessed December 28, 2015).

Balter, A. 2013. Access 2013—A Beginner’s Guide. New York, NY: Pearson Education.

Wu, T., and J. Blackhurst, eds. 2009. Managing Supply Chain Risk and Vulnerability, 1. Netherlands, Springer.

Koenig, K.L., and C.H. Schultz. 2009. Koenig and Schultz’s Disaster Medicine: Comprehensive Principles and Practices. Cambridge University Press.