Introduction

One of the greatest challenges in any type of Emergency Management is the consistent and effective communication of current status, information, and instructions to all participants in response to whatever crisis is occurring. Communications both into and out of the Command Center throughout the crisis must be effective; it is, by sheer necessity, a twoway process. In any crisis, human nature is such that if information and instructions are not received consistently by those on the front-lines and elsewhere in the organization, they will almost certainly be manufactured. Failure to adequately communicate with staff is almost invariably found to be the “root cause” of all “freelancing” by staff and all “rumor mills.” The only way to ensure that neither of these issues occurs is by ensuring reliable, ongoing, and robust communications with staff, from the very beginning of the incident.

Emergency communications will require the design of specific communications processes and strategies by the Emergency Manager for use by staff during the crisis event. These communications processes and strategies will differ from the day-to-day lines of communications, because while in crisis mode, the organization will be operating differently and will have different needs and expectations. The Emergency Manager will need to create specific methods and lines of communication in order to ensure the flow of critical information through the Command Center, thereby ensuring its function as a communications nexus and creating a “paper trail,” which documents every problem, request, event, and decision, in order to permit the organization the vital ability to demonstrate “due diligence” during any review, which occurs once the crisis has concluded. This chapter will focus on the creation of processes and strategies. Both communications technologies and documentation will be separately addressed in more detail elsewhere in this work.

Learning Objectives

At the conclusion of this chapter, the student should be able to describe both the normal and emergency communications processes within an organization and the characteristics of each. The student should be familiar with the potential problems and challenges posed by various types of emergency communications and the potential strategies to avoid or to overcome these. The student should also be able to describe and define the concept of “due diligence” and explain how this expectation can be satisfied through the documentation processes in use in the organization during any crisis.

Internal Communications

Effective communications are central to any type of healthcare organization, whether it is a large teaching hospital or a small, extended care facility. All services provided in healthcare rely upon effective communications. The manner in which communications occur in healthcare will be largely driven by the investments in communications technologies, which have been made by the organization. These can vary tremendously. At the low end of the technology spectrum is the simple bulletin board, while the balance can run through the gamut of telephones, overhead paging systems, computer-driven models, even handheld “smart” phones, and beyond this to RFID tracking of disaster patients within healthcare facilities. The more complex the communications technology employed, the more likely it is to be vulnerable to technological failures. It is essential for the organization to have a communications strategy for internal staff which is not only effective, but also robust. As in all Emergency Management activities, when addressing internal staff communications, two underlying principles should apply.

(Access webpage: www.bethesdahospitalsemergencypartnership.org/research_patinfo_rfid.html. Access Screenshot #2, and obtain permission for its use as an illustration. Caption: “In healthcare, the need for advanced communications technologies during a disaster can fill critical functions.”)

The first of these principles is multiple layers of redundancy. Every “critical” system, and internal communications must be among these, should have a primary system or method which is supported, in case of failure, by at least one other method of achieving the same function. Those situations in which Emergency Management operates are likely to represent a complex and challenging environment in most respects, and communications is no exception. Given the criticality of information to the healthcare process and, particularly, to the emergency healthcare process, it is absolutely essential to have “backup” systems wherever possible and to ensure that staff also know and understand these systems and how to use them effectively.

The second of these principles is technological independence. Each emergency “backup” system, including communications, should ideally operate on a completely different technology from the primary system which it is intended to replace. It is essential for the Emergency Manager in healthcare to understand the technologies which are operating, both as primaries and as backups. Otherwise, it is relatively easy to inadvertently establish a “backup” system which will fail at the same time as the primary system, primarily because both use the same technology, infrastructure, and operating systems. To illustrate, in a study conducted among Canadian hospitals some years ago, when asked how they would recall staff in an emergency if the telephones weren’t working, almost all immediately stated that they would use pagers!

Such results sound almost laughable in one respect, but, in truth, they simply reflect a lack of understanding of technologies among those tasked with creating and maintaining the Emergency Response Plan. The Emergency Manager who is operating in a healthcare setting does not need to be an expert in communications technology. They do, however, need to have at least a rudimentary understanding of the technologies of the systems operating in their facilities. It is also useful to know and consult those who are the resident “experts” in such technologies. They will be employees of either the organization or its contractors and are most likely, in the case of communications technologies, to be found in either the Information Technology or the Engineering Departments. Replacement systems which use the same technology are subject to the same vulnerabilities and should therefore be avoided.

It is important to remember here that, while we must at least understand the technologies involved and how their function, or failure, will affect our ability to communicate, what we are considering here is communications in the other sense. We are looking at the essential ability of the Command Center to provide both information and instructions to front-line staff and also our ability to gather important information from both staff and external sources, with which to drive the analysis and resolution of problems and the development and implementation of strategies. It is true that each type of communications struggles in the absence of the other, but the actual process of information flow is too often overlooked, or simply assumed, and communications technologies will be addressed adequately, elsewhere in this book.

Normal Communications

Every healthcare facility has its normal lines and methods of communication with staff, which are used successfully on a daily basis. There are also normal reporting structures and “chains of command” which keep the facility running smoothly during normal operations. Such tools are important, in that all staff have a clear understanding of precisely where information is coming from, who to turn to when a resource is required, and where to go when there is a problem that staff can’t fix.

While staff may contact some other departments directly, in most cases, staff will report to a front-line Supervisor of some sort. In the clinical setting, this is likely to be a charge nurse (in the United Kingdom, “sister”), or in some smaller facilities, the “most responsible” nurse. This person will, in turn, report to an actual manager, who may have a title such as nurse manager, nursing unit administrator, or even the classic “head nurse” (in the United Kingdom, “matron”). After hours, there may be a Nursing Supervisor in the facility, although with budget challenges, this “Nursing Office” role is becoming increasingly rare. The actual manager will, in turn, report to a director of nursing (in the United Kingdom, “chief nursing officer”), possibly through an assistant director, and in truly large organizations, this position may, in turn, report to a vice-president of nursing. Although the administrative structures of healthcare facilities are becoming increasingly de-centralized, this remains arguably the most commonly found administrative structure. Actual titles may vary, and the culture of the organization may modify the titles somewhat, but the structure itself is fairly consistently used. Through this portal, staff have appropriate levels of access to the administration and the normal management structure of the facility.

Communications may be verbal or it may be written, in either paper or electronic formats. For general information, healthcare facilities still rely on bulletin boards and, increasingly, on e-mail. Specific instructions may be delivered in person, by the Supervisor, or indirectly, particularly outside of “normal business hours,” using a tool which has various titles in different facilities, but which is most commonly referred to as the “communications book.” It is here that information and instructions can be left for staff working during periods in which the immediate Supervisor is not present and can also be used as a reference point for the balance of staff.

The communication becomes bidirectional when staff respond to information requests and new directives, using the same tools upon which they received the information. Staff tend to be comfortable with this system, and on a daily basis, it works well in most facilities. Other, non-nursing departments in most healthcare facilities use similar methods for staff communications, although the specific terminology used may vary somewhat. These communications systems and chains of command form the basis for daily information flow and work direction in most healthcare facilities. They tend, for the most part, to work well, and staff are accustomed to them and comfortable with their use. The problem with such processes is that, in healthcare, as in many large organizations, while the normal chains of command and lines of communications ultimately work, they tend to be very slow to operate, particularly when a decision, or the provision of specific work direction, is required. This is often because, while healthcare facilities tend to operate around the clock, key decision makers are rarely at the facility outside of normal business hours. An approach such as this is necessary in daily operations; it tends to eliminate the occurrence of costly or dangerous errors. While less than ideal from an Emergency Management perspective, this day-to-day reality is an important part of the culture of the organization; this model is what staff are accustomed to, and have become comfortable with.

Emergency Communications

In a crisis, time is typically of essence. Either patients require critical interventions and treatments to occur immediately, or the activation of the facility’s emergency response apparatus is required. This response apparatus, despite all of the emphasis on alerting procedures, takes time to actually activate, particularly outside of normal business hours, and it may be urgently required. Its activation cannot, and should not, have to wait until an administrator-on-call can get up, travel back to work, and assess the situation which is occurring, prior to actual activation.

While this approach may work fine for minor problems, it has the potential to delay the emergency response apparatus so significantly that it will become largely useless. A useful analogy here can be drawn from the Fire Service, which has an adage that “every thirty seconds without intervention, a fire will double in size.” Consider the example of finding a patient unconscious in the middle of the night and having to wait for that patient’s physician to arrive prior to beginning treatment, and the nature of the problem becomes evident. For these reasons, the first stage of the activation of any emergency response procedure must remain in the hands of front-line staff, and that staff must clearly understand that they have this authority and that they are expected to do this. For this to occur effectively, staff must be “pre-primed,” if not from experience, then with instructions. Such instructions must be provided, in advance, in clear, unequivocal, directive language, in the form of widely distributed policy documents and in the elements of the Emergency Response Plan itself.

This first stage activation will alert staff who are physically present at the facility to respond to the situation, notify senior decision makers, and begin to marshal the resources which are required in order to address the problem. While the appropriate person is responding to the situation, the assembly of the response apparatus has begun concurrently. An appropriate authority can always assess the actual situation once they are actually physically present, and then make a determination as to whether or not to continue with the activation. In the meantime, the actual activation of the emergency response is not unduly delayed and will be ready to begin operation that much sooner. This permits the organization to transition more quickly and effectively from a reactive stance to the proactive management of whatever emergency incident has occurred.

The next challenge for the Emergency Manager in staff communications will be the need for lines of communications and chains of command during emergency operations, which will differ significantly from those used on a daily basis. Human beings are “creatures of habit,” and the denizens of the average healthcare facility are no exception. Healthcare staff like the familiar; they know what they are accustomed to, and when this seems to disappear, particularly in the middle of a crisis, confusion and fear can be the result. The staff nurse who is accustomed to calling the Nursing Supervisor at 3 a.m. with a problem has no idea what the Command Center or the Operations Chief are; they are likely to be completely alien concepts.

Yet another challenge in staff communications will be the orientation of staff to lines of communications and chains of command which are significantly different from those employed on a daily basis. For the majority of front-line staff, this may not occur, as they will report to the person who is always in charge of their work area, but for front-line Supervisors, things will be significantly different. They will be providing information to and potentially receiving work direction from individuals who, particularly in a larger facility, they may have never met before. Given the nature of the operation, it is essential that such issues do not need to be addressed in the middle of the crisis.

For this reason, training on the Emergency Response Plan is required. While this may not be economically feasible for every staff member in an organization (although it should be!), such training is essential for any staff member who is likely to be left in charge of any nursing unit or other service delivery area of any healthcare facility, particularly after hours. By employing this strategy, the person in charge is the only one who understands, or needs to, that the chain of command and lines of communication have changed. For all subordinate staff, they will continue to take their problems and their concerns to the same person who is always in charge, and the changes which have occurred are largely invisible. Similarly, a downward line of communication has been established, and the Command Center staff possess a clear understanding of precisely who is in charge on every unit. They also know who to ask for resources and who to provide staff information updates to. While certain changes are absolutely required to facilitate the emergency response, the normal chain of command and lines of communication appear to be intact.

Staff Alerting Processes

When any healthcare facility experiences a major incident, particularly one which is likely to result in a significant demand for services, one of the first responses is invariably to marshal staff resources in order to meet the increased need. In many cases, the emergency may be adequately addressed by those resources which are immediately available in the facility. In the earliest stages of the emergency, this is invariably the case. As a result, any healthcare facility is likely to require two separate and distinct staff alerting processes, one for staff who are already inside the facility and, as the situation evolves and the surge in demand for services increases, a second method for use in attempting to recall the appropriate off-duty staff to the facility, in order to assist with the response. Each provides its own problems and challenges, and each will be discussed separately.

Overhead Paging

Historically, most hospitals have been equipped with one of various types of overhead paging systems. These systems, used to make announcements, including emergencies such as cardiac arrests, and to direct staff and physicians to specific locations, were often pressed into use as a method of alerting staff to the presence of emergency situations. There have always been two challenges presented by such systems. The first of these was the fact that, despite the best efforts of designers and installers, such systems rarely provided 100 percent coverage of the facility, so there were always “dead spots” where people could miss emergency announcements. The second challenge was the issue of limiting access to sensitive information, which could potentially frighten both patients and visitors and could cause panic.

While the coverage issue has rarely been successfully overcome, the approach to solving the issue of sensitive information was simpler. Most hospitals implemented a system of specific “codes,” which were used when paging staff to sensitive events on the overhead system. In hindsight, some of the earlier attempts were almost laughable in their simplicity—“paging Doctor Red, please report to the Maternity Ward,” which patients quickly figured out meant that there was a fire. Over time, situations evolved in which different hospitals used completely different codes for the same type of event. This had the potential to create potential confusion for staff who worked in more than one hospital. The author is aware of one jurisdiction in which the hospitals in one city used Code Purple to alert an incoming trauma patient, while in another city the same code meant an escaped inmate (there was a prison nearby) on the premises, and in a third city the hospitals used the code to alert staff to the presence of a VIP on the premises!

While there have been attempts to standardize these systems of coding events, there are still considerable discrepancies across jurisdictions, and hospitals continue to develop new codes in isolation, based upon their own identified needs. In Canada, the system standardization is better than in most locations, with a system developed by the Ontario Hospital Association being ratified by the Canadian Healthcare Association in 1993 and revisited by the Ontario Hospital Association in 2005. Concerns among hospitals continue to evolve locally, generating departures from the standardized model. To illustrate, many hospitals, located primarily in western Canada, have followed the lead of their American counterparts, introducing a Code Silver for an armed individual or active shooter on the premises; however, at this writing, this lead has not been followed universally.

In comparison, in hospitals in the United States, there is little standardization of emergency codes, and so the emergency codes used at, for example, Temple University Health System in Philadelphia are completely different from those used in the Florida Hospital Association standard. There has also been little standardization of emergency codes internationally, with U.S. hospitals having no standardization, but Canadian and Australian hospitals having completely different standards! To further confuse matters, in many communities the first responders (Police, Fire, EMS) and other agencies may use their own coding systems, in which the same code means something completely different from the code used at the hospital in the same community. To illustrate, in Ontario, Canada, a Code Red is a fire event in a hospital, but also a security lockdown in a public school!

One of the biggest single challenges with this type of system is that if the Emergency Manager is not careful, such a system has the potential to actually create more confusion than it was intended to solve! To illustrate, the world is an increasingly smaller space, and both medical and paramedical personnel have become increasingly mobile. It is not unusual for a physician or a nurse to train in one local jurisdiction and a few facilities within that jurisdiction, but then move to another city, state, province, or country. There are also, increasingly, economic challenges which result in staff who are, instead of achieving full-time employment in a single facility, working part-time in two or more facilities, in order to achieve the equivalent of full-time work hours. Each time that any of these individuals move, whether between two hospitals in the same community or from one large jurisdiction to another, they must relearn a completely different system!

While it will probably never be possible to achieve an international consensus on the use of a single set of emergency color codes, the Emergency Manager working in a healthcare setting should be, at a minimum, encouraging the development of a single, consistent set of codes, for use among all facilities within a given community or the larger jurisdiction. This is absolutely essential to the ability to deliver standardized emergency alerts which are clear, concise, and unequivocal within a given community, at a minimum.

Figure 4.1 Ontario (Canada) Hospital Association standardized emergency code

This technology is aging, but, surprisingly, is still in relatively common use. Some organizations employ these systems to alert all staff to emergency events, using either an emergency code system or plain language messaging. The advantages to such a system are that they are relatively inexpensive and that they work outside of the facility. Emergency alerting announcements can be sent as group pages, using readily available software from any appropriately equipped desktop computer in the hospital’s system. The challenges with such systems are that every staff member needs to have a pager for the system to work properly, and pagers are misplaced, lost, damaged, or, in some cases, simply ignored by staff members. Such systems provide no method of verifying that all pages to all staff have been received. As a further complication, while relatively inexpensive, this technology is continuing to age and is becoming increasingly difficult to provide technical support for.

Fan-Out Lists and Their Problems

The telephone fan-out list remains the bedrock of out-of-hours staff notification in almost all hospitals. Staff are required to report any changes in address and telephone numbers to administration, and each unit Supervisor is provided with a list of all of their own staff, which they are expected to use to recall off-duty staff during any emergency. When an emergency occurs and a staff call-back is authorized, either a group of people sits down in an improvised call center somewhere in the facility and attempts to contact all involved or the facility contacts all unit Supervisors, who, in turn, use their lists to attempt to contact all of their own staff, with varying degrees of success. Some facilities have simply fed all of this information into an automated “auto-dialer” device, in which a computer contacts every telephone number and provides an automated message to whoever answers.

There are several problems with such systems. In the first case, in this age of “Caller ID,” the sad truth is that many staff use this feature to screen calls from their employers, particularly when they are not interested in being called in for overtime work, as soon as they seen the hospital’s telephone number on the display. Such systems are also typically poorly maintained and has been said that in any system in an urban area which is not scrupulously maintained (updated at least every six months), the system will go out of date by about 20 percent per year, due to employees moving, leaving the organization, changing roles, and marital and health status. As a result, when fan-out lists are tested, it is not uncommon to achieve only about a 20 to 30 percent response rate. Sadly, the same result is often achieved in real-life events. The same problem is often true of unit leaders and physicians, as well. If the system contains only a home telephone number, and the unit leader happens to be out to dinner or shopping, the phone continues to ring, and no one on that person’s contact list will be reached! The third problem with such systems is that they tend to be remarkably nondiscriminating, often calling in every staff member who can be reached, whether or not they are actually required!

Virtually every healthcare facility employs someone with expertise in the development and use of computer databases and has one of the major products of database software, such as Microsoft’s Access, somewhere on their computer network. It is not a difficult matter, although somewhat time-consuming to set up, for a facility to move from old-fashioned telephone fan-out lists to a more comprehensive and useful emergency recall database. Using such a system, an information file is created for each staff member, including name, credentials, role within the facility, special clinical skills (e.g., Critical Care), other special skills (e.g., languages), all contact telephone numbers (often as many as four!), and the ZIP/postal code of the employee’s residence. This permits the system to be queried for contact information lists for employees who are actually required (e.g., registered nurse, Critical Care, within 20 minutes of the hospital by ZIP/ postal code), instead of summoning all members of staff. Such innovations can be extremely useful, although access to the database must obviously be controlled, due to potential staff privacy issues.

Newer Notification Technologies

Such recall systems may be improved with the ever-increasing improvements to technology in the field of “smart” phones. Such devices are portable and can be carried (at least in theory) by staff members at all times. A single text message can be sent out instantly to a great number of staff members. The technology is not foolproof, however. When such a device is not personal property, there is often a temptation to resist carrying it when off duty. As a result, such phones are often left at home, not turned on, or not charged when the staff member is not on duty. This can dramatically reduce the yield of staff during an emergency call out.

With “smart” phones, security of communications can also be an issue, particularly for a facility that is transmitting potentially sensitive information during any type of major incident. It must be remembered that, using either voice or data, a mobile phone is simply a two-way radio which connects to the telephone network. Without suitable encryption of data, it is potentially possible for “eavesdropping” to occur, most often by the media. As a result, such telephones should contain the best security that is currently available. At this writing, the only manufacturer which claims absolute security on its telephones and network is Black-Berry. This being said, the technology of this industry is in a constant state of flux, and the Emergency Manager will need to make a careful and impartial evaluation of all options prior to any recommendations for large-scale purchase.

Yet another challenge to overcome is that of cost. With the technology costing literally hundreds of dollars per unit to purchase, plus the operating costs, moving the facility’s entire emergency communications system to this mode of communications can be a costly undertaking. Even a medium-sized general hospital will have literally a thousand or more employees. The cost of purchasing one device for each employee, even with volume discounts, is not inconsiderable. It is possible that such a purchase could be justifiable in the context if the system were intended to become the institution’s primary internal communications device, with Emergency Management communications being a secondary consideration. It may well be that, at least initially, only members of the management team would be provided with such devices by the hospital, with physicians and others being able to access the network if they purchase their own devices.

Potential Barriers to Staff Response

Even when staff can be accessed using fan-out lists, there is a very real possibility that they may not be available, due to issues in their personal lives. Such issues may include the fairly common issue of staff working in more than one facility and either already scheduled to work elsewhere or called back by another facility prior to your call. Childcare is also a major issue, as is elder care. Even pet care can pose a problem with callback. Hospitals tend to assume that a spouse will step in and that the needs of the hospital should take priority, but what happens when the spouse is a physician or another nurse? Who takes priority in a disaster, when the spouse is a police officer, a firefighter, or a paramedic? Other potential barriers include weather and road conditions or the simple fact that, like many employees, the staff member does not live nearby? All of these factors will affect at least some staff members and their ability to respond to an emergency call-back. Each must be identified in advance by the Emergency Manager and, where possible, provided for.

Keeping Staff Situationally Aware

The most effective Emergency Response Plans tend to ensure that all staff, at all levels, are kept constantly aware of the events which are evolving surrounding the incident. This includes not only up to the minute instructions, but also regular incident status reports. Professional crisis communicators speak of a “golden hour” in crisis response. If effective communications begin, both internally and externally, within that hour, rumors and speculation are less likely to gain a foothold or to confuse or otherwise damage the organization’s response to the crisis. Staff who are continually aware of events and status on an ongoing basis are much more likely to meet the objectives of the Emergency Response Plan, and the presence of reliable information will greatly reduce the operation of the “rumor mill.” The challenge then is to determine how much information is enough, how frequently it should be provided, and by what means.

Staff are typically interested in general information and in information which has the potential to affect them directly. In most respects, an edited version of the Situation Report which is shared with outside agencies will probably fill this need. This staff update should also be used to quell any rumors which may have developed, bearing in mind that the development of rumors is generally a symptom of a lack of credible information. The development and distribution of staff updates should generally occur in tandem with the provision of Situation Reports to senior staff and to outside agencies. In an incident management system or similar Command and Control model, the responsibility for this staff communications role will typically be given to whoever is assigned to the public information role.

It must be remembered that information provided to staff will be by no means confidential. The occasional staff member may provide such information to the media inadvertently or may even contact the media directly. Some will simply provide information to their own family members, in order to reassure them. In any case, information provided to staff will typically find its way into the public domain fairly rapidly. As a result, this must always be remembered when creating a process for updating staff. The information provided should be reliable and accurate, but should be assessed by those in charge for confidentiality, prior to release. Information can be provided through regular briefings of supervisory staff, through a “Situation Report” circulated to all units or through a mass e-mail procedure.

Emergency Instructions

Whenever a specific contingency can be foreseen by the Emergency Manager, it is generally useful to plan in advance for its response. Once the desired response is determined, it can be made available as a set of clear, concise, unequivocal instructions to staff. The provision of such instructions can greatly reduce the level of “guesswork” and “freelancing” involved in the response to the situation. Such instructions are also extremely useful when a situation occurs outside of normal business hours, where typically, particularly in a healthcare setting, senior decision makers are not on hand, and may take an hour or more to respond, once they are notified.

The use of step-by-step checklists for staff can be highly useful for such procedures; not only do they provide concise, easy-to-understand instructions for staff to follow, they can also provide an appropriate level of documentation for exactly what has occurred. The written format, once completed, will also help to demonstrate an appropriate level of due diligence for the organization. This technique is drawn directly from the “standardized work” doctrine of Six Sigma, used to eliminate deviation and error, even when direct supervision is not readily available. For such tools to work, they must be readily available, and it is suggested that they be incorporated directly into the Emergency Response Plan, ideally as annexes at the back of the document. Staff are much more likely to follow instructions that they do not have to search for, and this is a reflection of the Lean approach to healthcare, in which time spent searching for information is considered to be “waste” and requiring reduction or even elimination. Information should “flow” to staff with minimal effort and without having to search. Even without such recommendations, on a simple, practical level, most experienced Emergency Managers know from experience that if a staff member cannot access instructions within about 10 seconds, they will toss the plan to one side and do whatever they think best—in other words, “freelance.”

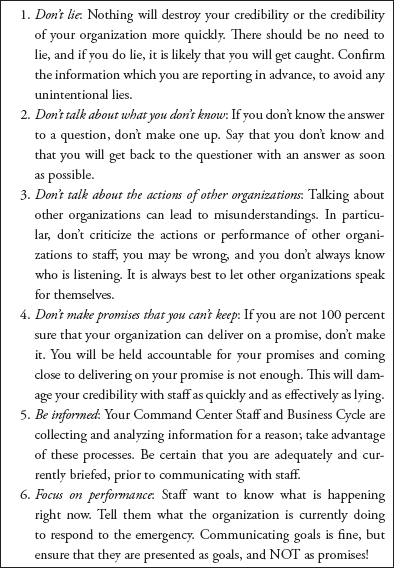

Figure 4.2 Tips for communication with healthcare staff in emergencies

Example: This evacuation checklist ensures that essential instructions are identified and created in advance and delivered to staff in a clear and concise manner, in order to eliminate confusion.

Two-Way Communications

As in all emergency situations, it is essential that the flow of information remain bidirectional, and this is particularly true with internal crisis communications. While the efficient and effective downward flow of work direction from the Command Center to front-line staff is crucial, so is the flow of information regarding current status, performance, problems encountered, and resource requirements from the ground up. Without such information, all Command Center decisions would be based upon a combination of external information and guesswork. In any healthcare setting, the Emergency Manager must analyze the available day-to-day lines of communications and communications technologies and will determine whether these are likely to work within a crisis situation. Will they work during a crisis? Will they be the same, or are changes required? What types of changes and how will these be accomplished?

It is important to remember that while all crises are problems, not all problems are crises. If a problem is identified, addressed, and remediated quickly, it is far less likely to become a problem during any future crisis. The time to discover problems and implement changes in crisis communications is most definitely not while the crisis is ongoing, if this can be avoided. In identifying potential internal communications problems, there will be three major potential shortfalls to be considered. The first of these is that normal internal communications technologies may be unreliable or may not be functioning at all. The next problem is that the lines of communication and “chains of command” may differ significantly from day-to-day operations, meaning that staff are unsure who they are reporting to or exactly who and where to take a resource issue or other problem to. Finally, in the absence of clear advance direction, front-line staff will be unsure what information the Command Center requires, when the information is required, or how to get it there. All of these potential issues should be amenable to resolution in advance.

By identifying potential communications shortfalls well in advance of the occurrence of any emergency, the advance mitigation of such problems becomes feasible. The actual physical study of the problem identified in the process, including such tools as root cause analysis and Ishikawa diagrams, can isolate what needs to be fixed and can help to develop the required changes in daily processes and procedures, in order to meet the needs of effective emergency communications. Since these changes are likely to be significant departures from the procedures that staff are accustomed to, they will need to be formalized, either through training or through the incorporation of clear, concise, step-by-step instructions, ideally included in the case-specific instruction checklists which are part of a good Emergency Response Plan. Careful planning and advance preparations for internal communications should be an essential component of any healthcare facility’s Emergency Response Plan.

Internal Situation Reporting/Updating

The Command Center needs to have the best possible understanding of the incident and of how it is being responded to at all times. The Incident Manager and Command Team also need to know about problems which have been encountered quickly, so that they can be resolved and so that their occurrence elsewhere in the facility can be prevented. This has to be weighed against the need to ensure that the Command Center is not inundated with a constant barrage of telephone calls from people who want to feel that they are contributing and want to learn what is happening. This process is already formalized with the members of the facility’s Senior Management Team, through the periodic distribution of the Situation Report from the Incident Manager. A similar, parallel process is required for the facility’s front-line staff and first-line Supervisors, and it is best developed in advance by the Emergency Manager and practiced in advance by those on the Command Center Team.

This process begins with the decision to activate a response to whatever the emergency happens to be and the announcement of the response. This normally occurs with the type of “code” announcement previously discussed, occurring on the overhead paging system, pagers, the telephones, or the computer network. This alerts staff to the fact that something abnormal is happening and should ideally refer them to a specific source (the Emergency Response Plan) in order to access specific instructions as to what to do in response to this information. If this process is developed well in advance by the Emergency Manager, ideally a set of specific instructions for each type of “code” in a clear, concise, and easy-to-understand checklist format should have been developed in advance by the Emergency Manager, and appended to the back of each unit’s Emergency Response Plan as an easy to find annex. When the announcement is heard, staff go to their copy of the plan and access the appropriate checklist. As each instruction is completed, the time is noted, and it is initialed by the person in charge. When the checklist is fully completed, it is physically taken to the Command Center, thereby ensuring that the Incident Manager can verify that, throughout the facility, each required measure has been implemented and is in place. This initiates the formal line of communication between the Command Center and every workplace in the facility and reflects Lean for Healthcare at its very best.

Effective communications must remain bidirectional throughout the response to the emergency, and this can be a challenge for the Incident Manager. While it is true that specific information and updates are likely to flow in parallel processes to other members of the Command Team, periodic generic situation reporting is also required. While such reporting to staff probably should not contain the degree of information or candor which is provided to senior management, a “scaled-down” version of the Situation Report, with content determined by the Incident Manager, should be sent to every unit which has completed and forwarded their checklist (these can be assumed to be functional).

This secondary Situation Report can occur either as a physical document or in electronic format, with the Scribe building an e-mail “group” and simply sending one report to multiple locations simultaneously. As with the primary Situation Report, this should be issued once each Business Cycle, ideally following the conclusion of each Business Cycle meeting. Similarly, the Emergency Manager may wish to give some thought in advance to the development of a situation reporting form or mechanism for use by the front-line Supervisors of each unit or work area and what that should include. Along with the development of the actual document should be an expectation that this report would be completed and sent to the Command Center once each Business Cycle.

The Emergency Manager should seriously consider employing the facility’s e-mail system for this bidirectional process. It provides a measure for easily updating information in both directions, without the telephone system constantly disrupting the Command Center’s business environment. In addition, everything which is placed on the e-mail system creates a permanent record, and it will be much easier, with the assistance of the IT staff, to identify precisely what information was provided to whom, by whom, when this occurred, and also any response. “Instruction ‘X’ was sent to every work area in the facility at 0600 hours, had been opened (and presumably read) by every work area in the facility by 0610 hours, and had generated acknowledgement responses from every unit (and was presumably understood) by 0630 hours.” It should also be stated, however, that while such a system is wonderful when it works, the Emergency Manager should also develop a “backup” paper system, which accomplishes the same objectives, for use if the computer system is not working.

Information Requests

One of the biggest challenges of the Command Center is likely to be a central component of its success. The Command Center should be designed to become a nexus of information for those responding to the crisis. As such, all information, and all information requests, should flow through the Command Center. This is essential, since information is the currency of Emergency Management. As such, those in charge must have access to the best possible information upon which to base their decisions. Understanding this, others in the organization will turn to the Command Center in order to access the information which they require. While there is some need to “edit” what information is disclosed and when (the role of the Incident Manager), the information flow process should be, for the most part, transparent. In any crisis response, if the Command Center is being bombarded with constant requests for information, it is an important indicator that the outward information flow is inadequate and requires adjustment.

The challenge with this is twofold; first, useful information tends to be carried along in a sea of well-intentioned minutia, and those receiving the information can be easily overwhelmed. The information received must be filtered, then validated, sorted, filed, and made available to those who require it. To illustrate, the Incident Manager does not need to know where an urgently required supply truck is coming from, its route, road obstructions, and so on, but does need to know that the supply truck is en route and what its expected time of arrival is.

The second challenge is the tracking of information requests, in order to ensure that none of these are lost or overlooked in the confusion of a busy Command Center. For this reason, the Emergency Manager will need to design a tracking system for information requests, which ensures that nothing is overlooked and that there is accountability throughout the process. As an example, a request for information on the availability of other hospital beds in the region is recorded on a request form, along with the name of the person requesting it, the time requested, and their contact information. From there, the request is assigned to a specific individual to be filled, in this case, the Planning Chief. This information is then recorded, along with an expected time of completion, on a whiteboard in the Command Center, where it will remain until the information has been obtained and returned to the requesting party. The whiteboard becomes a tool with which the Incident Manager can monitor progress, and, if requests are not filled in a timely manner, remind the person assigned. Once the information has been provided, the time of completion is recorded on the form, which is then passed to the Scribe, who will record the information in the Event Log, file the request, and remove it from the whiteboard. In this manner, the “loop” on information requests is always closed, and nothing is overlooked.

Resource Requests

Requests for resources will also typically flow through the Command Center and will require monitoring and tracking similar to that used in the management of information requests. Such requests can be urgent, and, as such, dynamic tracking is required, along with active monitoring by the Incident Manager in order to ensure completion. The Emergency Manager may wish to create a separate, parallel system for performing this function or may also opt to develop a joint information/resource request tracking and monitoring system. In either case, it is essential that the process be developed and the staff trained in its use in advance, so that they are not attempting to learn a system which is outside of normal logistical and communications channels in the middle of a crisis.

Upward and External Communications

Reporting to Senior Leadership: While the Incident Manager and the Command Team will be, for the most part, running the facility’s actual operations for the duration of the emergency, this fact does not exempt them from an obligation to ensure that the regular Senior Management Team, and particularly the Chief Executive Officer, are continually aware of events. Such events include not only what has been occurring, but also what decisions have been made and why they were necessary. The Senior Management Team are ultimately accountable for the facility’s success/failure in the response to the emergency, and so, they must be kept advised at all times.

Of particular importance is the ongoing reporting of expenditures which have been required in order to respond effectively to the emergency. The Incident Manager is, by no means, provided with a “blank cheque” to cover the costs of decisions made. Most good Emergency Response Plans contain a specific provision for spending authority for either the Incident Manager specifically or for the Command Team collectively, and one of the major duties of the finance role is to document expenditures as they occur and to provide periodic reports on expenditures to date and a final report on response costs, to both the Incident Manager and the Senior Management Team. Any expenditures which go beyond such pre-established arrangements will require the approval of either the CEO or the entire Senior Management Team.

Of equal importance is the fact that the members of the Senior Management Team, when kept “in the loop,” are often capable of performance functions and services in support of the Command Center, which are often beyond the capabilities of both the Incident Manager and the Command Team members. To illustrate, there is an excellent chance that the Head of the State or Provincial Health Department is at least acquainted with (if not on a first-name basis) the CEO of the facility, but probably has no idea who the Incident Manager is. Such individuals are also much more likely to be on the “through list” of various elected officials, the CEOs of major suppliers, and association heads than is the Incident Manager.

In any crisis, there is a great deal of communication, information exchange, and resource sharing that occurs through “back channels,” and, if properly informed, such individuals can help the Incident Manager to exploit these. Similarly, these individuals are typically managers of vast experience and, when properly informed, may be able to anticipate problems and devise solutions to situations which have not yet occurred to the Incident Manager, helping to drive the “proactiveness” of the response. This is not to say that they should be wandering into the Command Center and potentially disrupting the Business Cycle, or constantly calling the Incident Manager for information, but by keeping such individuals appropriately informed, a great many problems can potentially be avoided. This group is accustomed to working together, and for the purposes of communications, it is probably best to allow them to have their own parallel process, with the Incident Manager providing periodic Situation Reports to the CEO, who will, in turn, share these with the balance of the Senior Management Team.

The Situation Report (Sitrep): Within the larger field of Emergency Management, the formal Situation Report or “Sitrep” is considered to be a necessary component for the good management of incidents, and there is no reason why the experience of the healthcare field should be any different. It is considered to be an essential part of both “upward” and “outward” reporting of incident status by the Incident Manager. The Situation Report, or some local variant of this document, can be found around the world, and at all levels of government, as well as in emergency response agencies and the military.

While some elements of such a document are standard, including elements such as date, time, person reporting, weather, issues identified, issues resolved, and goals and objectives, other elements for inclusion will vary according to the type of agency or organization which is creating the report itself. Local variants of information for healthcare settings might include total patients onsite, total who have received treatment at this report, total of remaining patients awaiting treatment, staffing and resource shortfalls, and other supports required.

Such reports are typically created and issued once during each Business Cycle, usually at the conclusion of the Business Cycle meeting, when the information gathered is at its most current state. Neither of these lists is exhaustive, and the Emergency Manager will need to develop a template for the Situation Report in advance of any emergency, determining more precisely what information actually needs to be shared by the healthcare facility in question.

Outside agencies/governments: One of the first issues related to emergency communications with outside agencies and other levels of government that the Emergency Manager working in a healthcare setting must understand is that such organizations typically know little or nothing about the healthcare organization’s business operations. Their knowledge of the business of the healthcare facility is based largely upon assumptions, along with a healthy dose of the depictions of healthcare facility’s emergency operations by primetime television, neither of which is usually particularly accurate.

As a result, their expectations of the healthcare facility’s capabilities and capacities are often a matter of both misinformation and “blind faith,” and in no way reflect either your operating realities or any significant amount of advance dialog. They will simply assume that, just as on television, your facility can cope with any type of challenge that is sent to it. For this reason, many municipal and outside agency Emergency Plans (EMS/Ambulance Services are a significant exception) are likely to address the issue of all injured victims by simply stating that they will be transported to the local healthcare facility, with little or no understanding of whether the healthcare facility has the resources to provide the needed care. The situation becomes even more pronounced when there is only one healthcare facility in the community that is writing the plan.

What is required is advance dialog between all of the healthcare providers within a given network, in order to clearly identify who can do what, and who cannot, as well as exactly what services each facility is prepared to provide during a community emergency. Such arrangements need to be formalized in advance, in terms of mutual assistance agreements which are specific to healthcare. An amazing standard of mutual aid is feasible, but the time to attempt to negotiate it is not in the middle of a crisis. The Emergency Manager from the healthcare setting also benefits from becoming more collaborative with colleagues working in the municipal environment and in other levels of government. Once the agreements between healthcare providers have been formalized, it is important that this information be communicated effectively to the larger community and other levels of government, and the Emergency Manager from the healthcare setting can effectively play the role of both teacher and ambassador.

Exchanging information: An essential component of effective emergency communications is the use of “plain language,” particularly in communications between the various agencies. It must be remembered that every one of these organizations has its own native jargon. Jargon can best be described as a form of verbal “shorthand” which can be highly effective when everyone understands the same words and terms in the same manner. Most specialist jargon sets do not come with a glossary of terms. Where two types of jargon collide, it can actually become a highly effective barrier to useful communication. As but one illustration, the term “M.I.” in healthcare has become a standardized abbreviation for the medical term “myocardial infarction” or a heart attack. In many police forces, however, the same “M.I.” term is often shorthand for “mentally ill” among police officers. It is not difficult to see the potential for a catastrophic miscommunication to occur. This is a relatively common problem between clinicians and the general public, and emergency interagency communications pose similar issues.

The same problem can occur when the healthcare facility’s front-line staff, or Command Center Staff, for that matter, are attempting to communicate essential information to outside agencies in the middle of a crisis. In all outside agency communications, including meetings, telephone calls, e-mails, and Situation Reports, it is absolutely essential that all jargon be set aside for the duration of the emergency, and communications conducted in plain language.

“Back channel” telephone numbers: In any crisis response, one of the first problems which occurs is an overloaded telephone system. In North America, the telephone system is designed to cope with the use of about 20 percent of all individual telephones simultaneously. In many parts of the world, the capacity is considerably lower than this. In many telephone networks, the sound of an accelerated “busy” signal indicates that the network itself has reached capacity. This is increasingly important, as one of the most common responses to any emergency is for everyone who is remotely near the emergency site to begin using their mobile telephones simultaneously, leading to frequently overloaded networks. The internal telephone networks in healthcare facilities, and, indeed, in those of most public agencies, typically have similar load capacities and are frequently overwhelmed in a similar fashion. Have you ever tried to call your local electricity utility when the lights go out?

Given that good channels of communications are a major part of the effective response to any emergency, the prudent Emergency Manager will ensure that “back channel” telephone numbers, which are unpublished and do not run through the main switchboard, are available. A good choice for such numbers is any older technology analog telephone lines, which remain in the facility. Since analog telephones draw their operating power directly from the telephone line itself, while modern, digital telephones require a separate power source, these analog “back channel” lines should continue to work, even during a power failure.

By exchanging such numbers, in the strictest confidence, with emergency services, the municipal Emergency Manager, and senior government agencies, it becomes possible for the municipal Emergency Operations Center to access the healthcare facility’s Command Center directly and reliably, probably bypassing two overloaded switchboards in the process. Such information must be maintained in absolute confidence, or its use will be lost, and it must be exchanged on a “like for like” basis, if such a communications strategy is to be an effective tool.

Conclusion

Effective communications processes are critical to the successful response to any emergency situation by a healthcare organization. Such processes fulfill several key functions and satisfy a number of essential requirements. Such processes provide both broad and selective alerting of an ongoing emergency to patients, families, staff, managers, and outside agencies. They provide essential emergency instructions to both patients and staff. They provide staff with clear and unequivocal instructions for the use of procedures and processes which may not be a part of day-today operations. The use of these processes, and their associated documentation, can assist staff with the comprehensive, real-time documentation of events, problems encountered, discussions, decisions made, response strategies, failures, and successes. Such documentation will assist any healthcare facility in the critical need to be able to demonstrate “due diligence” in any type of review which may follow the conclusion of the emergency event.

Such processes do not generally involve the same procedures which are used on a day-to-day basis, and, as a result, may not be immediately familiar to all staff. For this reason, they cannot be simply created in the middle of a crisis; such processes require careful design and testing in advance. Staff will need to be trained in their use, and clear, step by step, easy-to-access and understand instructions will need to be created in advance and incorporated appropriately into the Emergency Response Plan of the organization.

This is an essential role for the Emergency Manager in a healthcare setting. The creation of procedures and processes which meet the specific needs of the organization and reflect its “culture,” from the use of telecommunications equipment and technologies to specific written communications and documentation/reporting processes, is an essential advance preparedness procedure. With careful thought, experimentation, testing, and training, such procedures can become an essential part of the healthcare organization’s planned response to any emergency.

Student Projects

Student Project #1

Conduct a detailed review of the potential technologies, processes, and approaches used for the recall of off-duty staff from various types of organizations during any emergency. Identify the strengths and weaknesses inherent in each. Now select one healthcare organization and review its procedures for the recall of off-duty staff in an emergency, again identifying the strengths and weaknesses of the system. Create a new emergency staff recall procedure, using what you have identified as the best of the technologies and procedures revealed by your research, and justify the use of each. Now create a proposal for the adoption of the selected process by the organization, explaining and justifying your choices and decisions. Ensure that the report is fully cited and referenced, in order to demonstrate that the appropriate research has occurred.

Student Project #2

Conduct a detailed review of emergency color code systems which are in use in hospitals and healthcare facilities in your own community, your country, and around the world. Conduct a search in order to determine whether there is any legislative, regulatory, or standard mandated for use by your facility. Now, select an emergency color code system (it does not have to be original) which would best meet the needs of your own facility. Create a proposal for the adoption of this emergency color code system, identifying its source, your rationale for the choice, and measures and timelines required for its successful implementation within your facility. Ensure that the proposal is fully cited and referenced, in order to demonstrate that the appropriate research has occurred.

Test Your Knowledge

Take your time. Read each question carefully and select the most correct answer for each. The correct answers appear at the end of the section. If you score less than 80 percent (8 correct answers), you should reread this chapter.

1. In selecting an emergency communications system for a healthcare setting, the Emergency Manager should be guided by two primary principles, those being the use of multiple layers of redundancy and that:

(a) Backup systems must be technologically independent of primary systems

(b) The infrastructure of the primary system should always be used

(c) For the Emergency Manager expertise in both systems is essential

(d) All of the above

2. When selecting an emergency code system for use in the alerting of staff using overhead paging systems, one of the greatest single challenges is:

(a) Getting staff to remember the codes

(b) A lack of consistency in codes among facilities

(c) Regulatory restrictions

(d) Accreditation standards

3. In order for emergency instructions to staff to be effective, they must be:

(a) Detailed and preauthorized

(b) Indexed for ease of access

(c) Clear, concise, and unequivocal

(d) All of the above

4. In all cases where information is provided to staff, it must be assumed that it will:

(a) Remain confidential

(b) By no means remain confidential

(c) Be documented by staff members

(d) Be shared with news media

5. When communicating with staff during an emergency, it is important that the Emergency Manager should:

(a) Maintain a “positive spin” on any news

(b) Be informed and don’t lie

(c) Identify the failures of other organizations

(d) Promise to resolve each issue

6. When the need for measures or procedures can be identified in advance, the Emergency Manager should:

(a) Preassign these to specific individuals

(b) Preassign these to specific departments

(c) Develop checklist tools for their completion

(d) All of the above

7. In order to discourage the use of the “rumor mill” among staff and beyond, the efforts directed at effective internal communications with staff should begin:

(a) As soon as everyone has their story straight

(b) Within the “golden hour”

(c) Within the first eight hours of the start of the incident

(d) When the circulation of rumors becomes evident

8. In healthcare facilities, the normal lines of communication and work direction appear to move more slowly, in order to:

(a) Eliminate costly and dangerous errors

(b) Prevent runaway change

(c) Comply with Accreditation standards

(d) All of the above

9. The more quickly and accurately a healthcare facility can activate its mechanisms and procedures to an emergency situation, the more quickly the response will change:

(a) From proactive to reactive

(b) From reactive to proactive

(c) From abnormal to normal

(d) From normal to abnormal

10. In the interest of effective interfacility and interagency communications, the Emergency Managers should work in advance to provide for all emergency communications to be conducted:

(a) Using the jargon of the sending agency

(b) Using the jargon of the receiving agency

(c) Using standardized Emergency Management jargon

(d) In plain language

Answers

1. (a)

2. (b)

3. (c)

4. (b)

5. (b)

6. (c)

7. (b)

8. (a)

9. (b)

10. (d)

Additional Reading

The author recommends the following exceptionally good titles as supplemental readings, which will help to enhance the student’s knowledge of those topics covered in this chapter:

Ahene, J. and J. Whelton. 2010. Applying Lean in Healthcare: A Collection of International Case Studies (Google eBook). Boca Raton FL: CRC Press. ISBN: 1439827400, 9781439827406.

Haddow, G. J. Bullock, and D. Coppola. 2013. Introduction to Emergency Management. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN: 978-01241 04051.

Lukaszewski, J.E. 2013. Lukaszewski on Crisis Communication: What Your CEO Needs to Know About Reputation Risk and Crisis Management. Brookfield, CT: Rothstein and Associates. ISBN: 978-1931332668.

Manley, D. 2012. Emergency Management in Healthcare: An All-Hazards Approach. Oakbrook Terrace IL: Joint Commission Resources. ISBN: 978-15 99407012.

OHA. 2005. OHA Emergency Management Toolkit: Developing a Sustainable Emergency Management Program for Hospitals. Toronto: Ontario (Canada) Hospital Association. ISBN: 978-0886213282.

Stamatis, D.H. 2002. Six Sigma and Beyond: The Implementation Process, Volume 7 (Google eBook). Boca Raton FL: CRC Press. ISBN: 1420000306, 978 1420000306.