Introduction

The Emergency Plan is central to the process of Emergency Management; without one, the Emergency Manager is left to react to each crisis as it occurs, often with poor results. I would explain why it is important to have a plan (beyond stating “poor results”) and the value of the planning process. Historically, Emergency Plans have been generic in nature, using what has been described as an “all-hazards” approach, with a generic response process and a generic set of response tools, which were modified to meet the needs of whatever adverse event happened to occur. Generally, the “all-hazards” plan is a base plan, which is typically supplemented by hazard or incident-specific plans. In this respect, the healthcare setting has been somewhat more advanced with respect to Emergency Plans, with case-specific planning occurring for several decades now. This chapter will describe the process of writing an Emergency Plan, along with describing the most essential elements of a good plan.

This chapter will focus on the creation of the Emergency Plan for a healthcare setting, using the tools of Project Management,1 Lean,2 and Six Sigma3 wherever possible. The various approaches to plan creation will be discussed, along with specific procedures for creation of an effective Emergency Response Plan for use in a healthcare setting. The type of plan model being proposed is innovative and is intended to describe a “best practice” for the creation of Emergency Response Plans for a healthcare setting, one which is easy to follow and use and which satisfies all of the legal requirements, as well as the requirements of the accreditation process. It will incorporate the information already covered in Chapters 1 to 6, in order to help the student to create the most effective plan possible.

At the conclusion of this chapter, the student should be able to describe the various approaches to the creation of an Emergency Plan, describing the advantages and the disadvantages to each approach. The student should be able to describe the process of creating an Emergency Plan as a formal project and understand how to apply the Project Management process to the creation of the plan. The student should be able to describe the process for creating an Emergency Plan, including all the essential elements of a plan for a healthcare setting. The student should understand how mainstream business processes, such as Project Management, Lean, and Six Sigma, can be applied to the creation of an Emergency Plan, in order to make the document more effective. The how is the easy technical part—more important for students to understand the why and the purpose it serves.

What Is an Emergency Plan?

Emergency Plans will vary from organization to organization, and each is created, based upon the specific needs of the organization which created it and also upon the knowledge and skill of the author. The term “Emergency Plan” is somewhat generic. In the United States, such documents are often referred to as “Emergency Operations Plans,” while in still other jurisdictions, the term “Disaster Plan” is still in use. There are, however, some commonalities which should be explored. An Emergency Plan is not a step-by-step blueprint, intended to guide the reader through the entire emergency; this is a popular misconception. A well-written Emergency Plan is a roadmap of sorts, intended to guide the reader quickly and efficiently through the activation and the deactivation of the organization’s emergency response apparatus whenever adverse events preclude the use of normal, day-to-day plans. While some commonalities do exist, all emergencies, and their responses, are different; they deal, in large measure, with the initiation and the stand-down of the response mechanisms and resources; after the first hour, your will still have to “fly by the seat of your pants.” But staff will have established the response processes correctly, and now success or failure will be dependent upon the resources which are available and upon the judgment and decision-making skills of those responding to the emergency.

An Emergency Plan is a guide to the activation and deactivation of the emergency response process.4 An effective plan recognizes the fact that, in most healthcare facilities, key decision makers are not in the building 24 hours per day, and so, must provide approved and effective guidance to more junior staff, in order to function in those circumstances which cannot await the arrival of the more Senior Management Team. It is intended to provide clear instructions to staff who may have never encountered an (routine emergencies, minor, significant or major) emergency or had need to use the plan before, so that response is not delayed until senior decision makers can arrive.

An additional part of its function is to identify compliance with the legal and other official (e.g., accreditation) standards which have been placed upon the organization. The purpose of preparing the plan is not to meet accreditation, but rather to guide the organization through what the expected response is to an emergency. Having said that, the Joint Commission or like accreditation organizations will expect the healthcare facility to have an Emergency Plan and a program—and a plan is not an Emergency Management program. It identifies authority to act, procedures for activation and deactivation, spending authority, and accountability. Concept of operations—what is the plan? What is the strategy? What are the planning assumptions? What are we trying to achieve? What are the planning goals and objectives? How are we going to assemble as a team—in person or virtually—to make what strategic decisions? What strategic decisions should we be thinking about in advance of an emergency? What are our emergency procedures, and what kind of things do we need to have protocols/policies/procedures for? What are the expectations of the board? And the people we serve? It clearly explains the process that the organization intends to use in order to respond to the emergency, including the Command and Control system to be used, Key Roles and general emergency responsibilities, key emergency-specific facilities, and specific instructions for staff regarding specific issues (e.g., dealing with the media). As such, it is an essential method of demonstrating that the healthcare organization which created it has demonstrated “due diligence” in dealing with the response to emergencies. More importantly, executive leaders want to make sure that we have a plan in place should a disaster occur and want to be sure it is practical and that key staff are trained and know what to do.

Each organization has its own specific reasons for the creation of an Emergency Plan. While local, regional, and national laws generally operate in the case of communities, hospitals and other healthcare facilities are only sometimes specifically mentioned in legislation or regulations, and those regulations which apply to public hospitals may not necessarily apply to privately operated hospitals which receive no public funding. Indeed, many hospitals around the world are more likely to be compliant with the standards provided and monitored by one or more of the several international accreditation bodies which operate in healthcare. These bodies do understand the importance of effective emergency planning in healthcare facilities. It is regarded as an essential component of their periodic accreditation and is considered to constitute both good governance and due diligence! Plans were in place before they were mandated. Anybody that understands a bit about risks realizes you need a plan for your risks and hazards. Hospitals may or may not have a legal mandate for the creation of a plan; this is a matter for the pertinent legislation of the local jurisdiction. They do, however, generally regard the presence of an Emergency Plan as a best practice, and again, depending upon the organization, as an accreditation standard.

Long-term care facilities and other types of healthcare organizations may or may not be subject to regulations generated by pertinent governing legislation, but almost all are also subject to accreditation of some type. It is interesting to note that the accreditation issue, along with the fact that most healthcare agencies deal with emergencies on some scale on an almost daily basis (routine emergencies), has resulted in a far greater level of interest in the subject in healthcare, than in municipalities, which sometimes, unfortunately, simply regard their requirement for an Emergency Plan as “yet another unfunded mandate.” Why not make the case that institutions should factor in the cost of emergency preparedness no different than how they budget for equipment and for supplies. CEOs want a resilient organization and having a solid Emergency Plan is one aspect of resiliency.

The Emergency Plan as a Project

Like many of the advance aspects of Emergency Management, the creation of the Emergency Response Plan is, in fact, a project consisting of a series of smaller projects. As such, it is amenable to the principles and techniques of Project Management and, as previously demonstrated, with the creation of the Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment (HIRA).5 One of the major objectives should be, wherever possible, to create a plan which standardizes the work of responding to each type of emergency—a key principle of Six Sigma.6 If work is standardized, potential errors in performance can be reduced or eliminated, and it becomes possible to monitor individual performance for compliance; staff are more likely to use the Emergency Plan in the manner originally intended.

This is the time to look at the proposed response measures and methods critically. If the Emergency Manager is about to develop standardized work models, using checklists, for example, the plan creation process is the correct time to actually analyze the proposed measures critically. Analysis should occur even to the point of using the Value Stream Mapping techniques.7 Doing so is likely to identify weaknesses in current procedures and to identify and eliminate wasted time and resources. As a result, the opportunity is provided to potentially make many emergency response processes simpler and more efficient. The resulting processes are likely to be easier for staff to understand and remember and, therefore, less subject to error—once again, an opportunity to put the principles of Six Sigma in operation.

This is also an appropriate time to utilize applied research skills. Before implementing a technique or a process, take the time to ensure that the technique or process is the best one available. To illustrate, if the Emergency Manager is about to incorporate a mass-casualty triage process into the Emergency Plan, it is prudent to conduct a literature search on the subject, in order to identify whether a new model of triage which might better meet the needs of the organization is available. Similarly, polling or surveying other facilities, in the local region or elsewhere, might also identify specific information, which is useful, but was previously unknown. This can be a somewhat complex project, and certainly time-consuming for the Emergency Manager; however, time spent now by the Emergency Manager and others has the potential to greatly reduce or even eliminate time wasted by others, during any future crisis. Once again, this is a key principle of Lean for Healthcare.8

Figure 1.1 Value Stream Mapping can be applied to any process, including emergency treatment and throughput, to improve both efficiency and overall performance

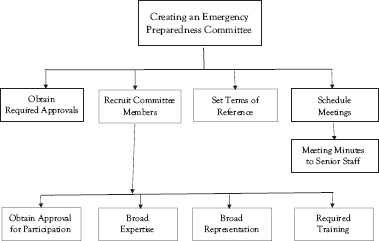

The creation of an Emergency Response Plan is also an opportunity for teamwork, collaboration, and consensus building, by the Emergency Manager. By creating an Emergency Preparedness Committee for the purpose of creating the plan, a number of critical objectives can be achieved. By selecting committee members from a broad range of the organization’s work areas, the Emergency Manager creates a pool of expertise about the organization, its strengths and weaknesses, and how it functions.9 By encouraging participation in the creation process by others, a sense of “ownership” and “buy-in” of processes and procedures, and even of the plan itself, begins to develop. The new plan begins to acquire a collection of “ambassadors” or even “champions” to the balance of the organization. Of course, in such a huge project, the significance of the old saying that “many hands make light work” should not be lost on the Emergency Manager! Even when some members of the group are not actually writing policies or procedures for the plan, they constitute a significant representative “sounding board” for those policies and procedures and will remain useful long after the Emergency Plan is completed. Build ownership among stakeholders.

The degree of complexity and of work required will be determined in large measure by the current state of the organization’s Emergency Response Plan. There are several variables which must be considered. If a plan exists, it may be possible to simply review and update the existing document, with appropriate updating of policies and procedures. This will largely be dependent on whether or not, in the opinion of the Emergency Manager, the existing plan could actually be operationalized during an emergency; an Emergency Plan which cannot be operationalized is essentially useless to the organization. Consider the potential usefulness of an “Emergency Plan” describing the use of resources or personnel which simply do not exist in the facility, and the impact of trying to rely on such a plan during an actual emergency event. Revision of the existing plan will also be determined to some extent on the plan format which was used by the previous author; is it in a format which is in current use, and will it lend itself to ease of usage for the staff? Risks are by no means static; issues such as facility operations, risks, and exposures to them are in a state of perpetual evolution, just like the facility itself. The facility probably bears only passing resemblance to what it looked and worked like 10 years ago; then why wouldn’t the development and pattern of both risks and risk exposure evolve continually, along with the facility itself? The process of conducting a formal HIRA process is annual and the plan needs to be updated and reviewed annually and following actual incidents, as you “build back better.”

Figure 1.2 The emergency prepared committee: Essential to the creation of an effective emergency preparedness program

The final factor which must be considered is the age of the existing plan. A plan which is more than two years old is considered to be out of date, in many jurisdictions. If an organization changes its structure and/or the responsibilities, the plan needs to change and adapt to what is new. Age is not the only factor. A plan can be out of date because legislation changed. Recent events and exposures, such as COVID-19, can also profoundly affect the currency of an emergency, with lessons learned from the event necessitating an immediate and complete revision of the plan. Any plan which is more than five years old is likely to be so far out of date in terms of both content and format that it is easier for the Emergency Manager to start again from the beginning.

For the purposes of this chapter, a project for the creation of a brand-new Emergency Response Plan for a healthcare institution will be described. The project is described in a linear manner, and the process of creation may be accelerated somewhat through the use of concurrent steps, if the Emergency Manager has the resources to do so. But building and maintaining a current Emergency Response Plan is an iterative process and the plan is a “living document.”

Essential Elements

In the past, most Emergency Plan documents were binders written in a narrative format and often very difficult in which to find appropriate information quickly. In many cases, within the healthcare setting, the tendency was to introduce the document to new staff during new employee orientation, but with little or no follow-on training. The difficulty of use of the document meant that the staff very rarely read any portion of the document on their own, unless an emergency occurred. During an emergency, the binder would often be pulled out to consult, but after difficulties were encountered in finding appropriate information, it would frequently be tossed to one side, and the staff would begin doing what they thought was best (freelancing). This was hardly surprising, since, in many cases, most members of the management team had never read the document either! There was a standing joke that the Emergency Plan provided valuable service as a doorstop in the CEO’s office, to be pulled out and dusted off a few months before accreditation was due. The value is in the process, so no one has to pull out the plan because they have learned it and should now have a one-page Job Action Sheet for all essential positions.

Figure 1.3 A logical project plan for determining whether to revise or replace an existing Emergency Plan

Figure 1.4 Formal hazard identification and risk assessment conducted during the planning process ensures that the plan remains relevant

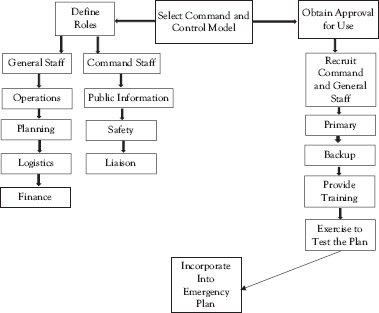

Figure 1.5 Choosing an effective and consistent Command and Control model increases plan effectiveness

All good contemporary Emergency Plans will contain certain key elements, each of which has its own purpose to serve. The staff should not have to waste large amounts of time searching for information, instead of doing productive work; this is an essential principle of Lean for Healthcare. Staff time is too valuable and important to be wasted! Each additional minute that a staff member has to spend searching for information is a minute that they are not spending on bringing the emergency event to a resolution, and the impact can “balloon”! To illustrate, if the incident is currently escalating, it will continue to escalate further every minute that remedies are not being applied. If the staff member is busy hunting for difficult-to-access instructions and deciding whether they have the authority to act or whether these instructions apply in this specific circumstance, the event will continue to escalate, and its results will continue to worsen, until the actual attempt to resolve the event begins.

The result is not only a waste of staff time, but also a potentially unnecessary amount of damage, disruption of service, economic loss, and, in healthcare, even the loss of lives. An Emergency Plan is supposed to assist and provide guidance to staff responding to an emergency, not to disrupt and delay that response! An appropriately written plan is divided into clear and distinct elements, in order to provide ease of access to specific types of information. These include the main body of the plan, annexes, appendixes, and Job Action Sheets. The plan is only a guideline and is only good until the ball gets hiked. That is why practice is important, because what you planned for may not be the real-life scenario, but many of the impacts you may face are the same across so many different types of emergencies. Patients may have to be evacuated for a number of reasons, but you have to have a strategy for multiple situations—slow onset (move most critical first) versus sudden with no warning (ambulatory first) horizontal, vertical, out of the building, and so on.

Main Body

The main body of any Emergency Plan is the part which, to the reader, looks most like a traditionally written plan. It deals with those issues which are universally applicable. These include authority to activate, incident command system, and spending authority. The style is primarily narrative and covers all of the legal elements required in such a document. Key elements include a title page, record of amendments,10 and a table of contents. It also includes a statement of authority, which identifies who specifically authorized the creation of this plan and may also make reference to specific legislation11 or industry standards, such as accreditation standards,12 which mandated the creation of the document.13 A statement of scope should also be included.14 This element identifies precisely, for the reader, what the plan document is intended to address and achieve and also what it is not intended to address and achieve.

The main part of the plan is the concept of operations: what is our strategy? How are we going to handle this crisis? What measures are we going to put into place, who is going to do what, what are the authoritative instructions that we need to issue? and so on. How do we communication internally, externally, and by what means—emergency mass notification system? In addition to identifying a Command and Control model such as the Healthcare Incident Command System (HICS)15 or

the Healthcare Emergency Command and Control System (HECCS),16 this section of the plan will also outline communications procedures.

This section of the plan will also identify the location, structure, and function of certain emergency-specific resources, such as the Hospital Command Center, family information center, media information center, and staff staging area, which will be determined by the nature of the emergency and the requirements of the facility to manage it. This section of the plan will also specify reporting requirements, including reporting to senior staff of the organization, the community itself, and senior levels of government. Finally, it will provide a clear statement of the authority to stand down and instructions on how this is to be accomplished, once the emergency event has concluded.

Which clinical specialties exist in what other hospitals, if there are even any nearby? If the facility must evacuate, who goes where? Which staff will accompany patients during evacuation transport? What is the procedure for various types of evacuations? Who has the authority to order any of these measures and under what circumstances? How will the healthcare facility interact with the municipal Emergency Operations Center? Does our plan rely realistically on local Emergency Medical Service for evacuation, or do alternate arrangements need to be in place in advance?

When composed according to the ease of access principles of Lean for Healthcare, the document should have not only a table of contents, but also numbered pages. Wherever possible, the format of the document should be “one issue per page” with any overflow being placed on the back surface of each page. A glossary of terms should also be included, in order to ensure that the reader has a precise understanding of the intended meaning of each key word or phrase, to eliminate any potential misunderstanding arising from misinterpretation.17

In addition to making information much easier for the reader to find, the manual may be designed so that staff using it may be able to literally pull out the relative page, using it as an instruction sheet, which greatly increases compliance with the content of the plan. Moreover, this type of formatting makes the maintenance of the Emergency Plan document much less labor-intensive for the Emergency Manager, since a needed change in a single policy or procedure requires the rewriting and replacement of only a single sheet (or at most, a couple of sheets) of paper in each manual. Give staff a badge buddy that goes on their lanyard. Put emergency info on the badge buddy—emergency call number of the healthcare institutions or a specific procedure for reporting an ongoing emergency and requesting assistance.

Each copy of the plan should be dated in order to ensure that the reader has access to the most recent version of the instructions, and each should be numbered, so that the Emergency Manager can track each copy and ensure that each copy is maintained with the most current information and instructions. Each page should include a date of creation, and the document tracking page, located in the front of the plan, should describe the date of creation for each page, and also the date of any amendments for that page, along with the reasons for the amendment.

Such measures, although time-consuming, will potentially provide great assistance in any public inquiry, inquest, or other legal action which arises from any emergency event. They provide tremendously valuable transparency as to the precise etiology of any instruction or policy statement, by describing the entire history of the issue, and providing the document with tremendous credibility in the eyes of those conducting the inquiry. It is also wise for the Emergency Manager to create a history file for each page, of the plan, storing copies of each new iteration of each policy or instruction, against a time when the reasons for the creation and use of that policy or instruction may require defense. A sample of the main body of a healthcare-based Emergency Response Plan has been included in Microsoft Word format, on the web page which accompanies this book.

The Annexes

The annexes are secondary plans in their own right, covering a potentially vast variety of subjects and/or situations. The base plan (all hazard) and the annexes (annexes for hazard or incident-specific plans based on your risks as well as functional plans (transportation, etc.)) instructions for particular events which are case specific, such as a specific set of operating instructions and procedures to be used for the evacuation of the hospital, or a response to a mass-casualty event. They may be narrative but are much more likely to be immediately useful if formatted as step-by-step checklists for each type of event.18 This approach embraces the Six Sigma concept of standardized work as a method of error reduction and provides tremendous consistency, in that every staff member will successfully respond to a given situation, if only they follow the items on the checklist in the correct sequence.

Additionally, the opportunity exists to have staff members literally remove the appropriate annex pages from the binder, placing them on a clipboard and writing on them directly, as each step in the process is completed. By initialing each step and noting the time of completion, the document will probably be admissible in any type of public inquiry, depending, of course, on the rules for each respective jurisdiction. Moreover, by simply having each checklist from each work area forwarded for review once completed, the Emergency Manager has the opportunity to collate these and to document chronologically virtually every step taken within the facility to prepare for response to the emergency in question. The Emergency Manager is also provided with the opportunity to monitor each location for compliance with the specific instructions for the emergency event, and to follow up when noncompliance has been identified. The annexes are relatively inexpensive, usually being produced by photocopying, and can be quickly and easily replaced with new unused copies, following each use.

Increasingly, many healthcare facilities use color coding to describe various types of emergencies. It is even likely, in most facilities, that the subject of a particular annex already possesses a particular color code. This color coding can be taken a step further, in order to make such documents easier for staff to find and access in the Emergency Plan, as per Lean for Healthcare. This might consist of color-coded tabs within the plan binder, and even color-coded pages containing the instructions. While this approach will work well within a facility, one significant drawback is that such codes have only rarely been standardized from one hospital to the next, and only then on a regional basis.19

The so-called “clinical” codes, including both adult and pediatric cardiac arrest, are not normally included in the annexes of the Emergency Plan for a healthcare facility. There are generally more than sufficiently experienced and knowledgeable professionals present to deal with such situations appropriately, and step-by-step instructions would probably be of limited value to those present. Several sample copies of Emergency Plan annexes have been included in Microsoft Word format, on the web page which accompanies this book. The situations in Figure 1.7 are those for which the creation of case-specific annexes may be appropriate for a healthcare-based Emergency Plan. The list is by no means exhaustive; every institution and agency has its own needs and experiences and may need to create an annex to deal with that specific event.

Figure 1.7 Case-specific annex scenarios

Job Action Sheets

These documents, as with the annexes, are generally checklists, although typically highly specific to a particular job or position, such as the Key Role positions in whichever Command and Control model the facility chooses to use. They may also be used to address any seldom used but necessary emergency response task, such as the assembly and activation of the Hospital Command Center from a kit.20 In each case, the instructions are sequential, specific, and easy to understand. They are intended for short-term use by inexperienced staff who are filling a Key Role on an ad hoc basis for the first time, until relieved by predesignated and trained staff. Talk about the benefits of a Job Action Sheet—disasters are stressful, and people are making decisions and taking actions without full information but based on what they know at the time. It is a reference, and then they know all of the key actions are being done and people can fill in for each other easily if they have their JAS and they have been cross-trained to it. They are of great value for a charge nurse, especially outside of normal business hours.

Job Action Sheets21 permit a tremendous strength to the organization, in that ad hoc untrained staff may be successfully used successfully (use same word) over the short term, in order to accelerate the activation of the response mechanism outside of normal business hours, an essential ingredient to successful response to an emergency by a hospital. One ordinary staff nurse might fill the role of Incident Manager temporarily, supported by a comprehensive set of instructions, until relieved by the designated Incident Manager, who at 2 a.m. is likely to be responding to the hospital from home. When they arrive, they are greeted by an ad hoc Incident Manager who has begun the steps outlined on the Job Action Sheet, all of which are already documented, and the process of ramping up for response is greatly accelerated.

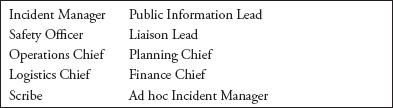

Job Action Sheets may also be used for guidance through highly necessary but seldom-performed tasks, such as the activation of the Hospital Command Center. By making a correct set of instructions readily available in the Emergency Plan annexes, in the scenario immediately preceding, the designated Incident Manager might very well arrive to find that the Hospital Command Center has already been assembled by support staff with no prior training and is already available for use. Such tools have the potential to greatly accelerate and enhance the response process 24 hours a day. It is possible to create such Job Action Sheets for as many roles as the Emergency Manager has the time (and the energy!) to create; however, what follows in Figures 1.8 and 1.9 are lists of Job Action Sheets which should be considered essential. Several sample copies of Emergency Plan Job Action Sheets in Microsoft Word format have been included on the web page which accompanies this book.

Figure 1.8 Job Action Sheet: roles

Figure 1.9 Job Action Sheets: essential tasks

The Appendixes

The appendixes are composed of information which, while highly necessary for the Incident Manager and those in the Hospital Command Center or the Senior Management Team, may not be appropriate for sharing with potentially everyone in the facility or with outside agencies with which copies of the organization’s Emergency Plan might be shared. These would include all staff off-duty contact information, including all relevant telephone numbers for each staff member and their work schedule. While such information is essential to have during a crisis, it is also understandable that most staff, particularly those with potential security concerns, would not want this information in general circulation. Similarly, having a detailed contact list for all members of the senior team, the management group, and the incident management team is essential, but should not be generally available to staff. Other numbers which would not be for general distribution would include the “back channel” telephone numbers for other healthcare partners, emergency services, the municipal Emergency Operations Center, or other government agencies. Finally, a contact list for all of the organization’s suppliers and contractors, specifying exactly what they provide, purchase order numbers, and 24-hour contact information, is an essential tool for the command center, but not wise to have in general circulation. Under normal circumstances, it is anticipated that the modern facility would store all of this information on computer databases in the Hospital Command Center; however, paper copies of each type of document are still required, against the possibility that the computer system becomes unusable, for any reason.

All of the aforementioned information should be included in the master copy of the Emergency Plan and in all copies of the plan located in the Hospital Command Center. Beyond that, whether or not a particular element of information is appropriate for inclusion in a particular copy of the plan will need to be decided on a case-by-case basis, by the Emergency Manager. Protocols are an important component of an Emergency Plan. Think about COVID-19. Lots of protocols support the COVID-19 base plan, for example, donning and doffing procedures and waste management.

Making Information Accessible

Information, however well intended, is completely useless, unless it is readily accessible by those attempting to find and use it. It is frequently for this reason alone that many Emergency Plans fail, when required. In a healthcare setting, in the middle of a crisis, the person who picks up the Emergency Plan binder to find an element of critical information will frequently discard the binder and improvise, if they cannot find the required information in under about 10 seconds. The information is, in all probability, actually present in the binder, but the combination of old-fashioned narrative writing, difficulty in finding anything, and poor maintenance of the binder often make that information almost impossible to locate quickly.

If the Emergency Manager is to make the Emergency Plan into a document which is perceived by staff to be useful and worthwhile, substantial changes in accessing information will need to take place. It is necessary for the Emergency Manager to put into place and to achieve a goal of permitting any untrained user to access any key element of information within the Emergency Plan in 10 seconds or less. There are many number of traditional approaches to making information accessible which may help to achieve this goal, and also several relatively new ideas. The traditional approaches include numbering pages and tables of contents, as well as the provision of tabs for individual elements of important information. More recent innovations include the writing philosophy of “one page, one issue,” the color-coding of both tabs and, in some cases, pages, and the provision of all associated documents immediately adjacent to the task being described, thereby avoiding any need to search for them.

The division of the Emergency Plan into specific sections, separating the tedious but necessary legal requirements from key information, makes searches both faster and more productive. In some cases, it involves making the associated documents become the actual instructions for action. Finally, since many adults react best during a crisis to visual information, making information accessible may involve the incorporation of flow charts where appropriate. Each of these opportunities will be discussed in detail.

The traditional approach involves making the Emergency Plan less like a binder and more like a book. It provides reference information which the reader has seen before, and already knows how to use, requiring no further training or instruction. This involves the numbering of each page in the plan and the creation of a table of contents, at the front of the binder. This can be further enhanced by the adoption of a writing practice of “one issue, one page,” with all of the information for a single issue being presented on a single sheet of paper, with any overflow from the front face being added to the back face of the page. If all the reader wants to know about is who has the authority to activate the Emergency Plan provisions, they can turn directly to that page and access the information, much as they would do in a conventional book. This approach has several advantages; not only can information be accessed quickly and easily by the reader, but when a change in policy or procedure occurs, the Emergency Manager has only to rewrite and replace a single page in each binder, greatly reducing the amount of maintenance required and promoting the currency of information.

The Emergency Plan document may be further enhanced by the division of the Emergency Plan into the main body, containing purely legal and policy information; the annexes, which include case-specific response directions for various issues, such as a missing patient or a bomb threat; role-specific instructions, such as the Job Action Sheets; and task-specific instructions, such as the assembly and activation instructions for a key emergency resource. Finally, it includes the appendixes, which include key elements of information which may be urgently required by some during an emergency response, but which, for reasons of privacy, are not made immediately accessible to all. To illustrate, it is essential, even at 2 a.m., for the Incident Manager to be able to contact the hospital’s CEO at home, and this call is welcome, while a call at a similar hour from a disgruntled nurse who hasn’t had a meal break would be somewhat less welcome.

The information included in an appendix is always placed in the master copy of the Emergency Plan, and in each copy used in the Hospital Command Center, but its presence in other copies of the plan is determined on a case-by-case basis. This design divides all information into clear categories of “need to know,” “nice to know,” and “may require.” The provision of a glossary of terms and acronyms is intended to clearly express the intended meaning of terms used in the Emergency Plan, thereby eliminating any confusion caused by interdisciplinary jargon disconnects. These design features permit the reader, once the configuration is understood, to narrow their searches and to quickly access only the type of information that they actually require.

The incorporation of annexes which are case specific, role specific, or task specific, provides clear and precise step-by-step instructions to staff in a variety of circumstances. In the case-specific approach, the instructions for action in any specific situation are provided. Most healthcare facilities use this approach for the division of events, but actual approaches vary. To illustrate, if it is 2 a.m. and the fire alarms begin to sound, the new staff nurse or the agency replacement nurse, neither of whom has ever participated in a fire drill in the facility, can quickly access specific instructions for what to do by pulling out the Emergency Plan binder, flipping it open to the tab for “fire,” and following the step-by-step instructions from start to finish. Access to the critical information took mere seconds and was almost intuitive in its provision. There is the elimination of waste principle of Lean for Healthcare at its finest; the staff member wasted absolutely no time finding the information, thereby increasing the speed of response to the crisis.

The documentation process can be further enhanced by the use of that particular annex as a worksheet: physically removing the annex from the binder, if necessary, ticking off each item on the list as completed, noting the time of completion, and initialing beside each entry. In this manner, the instruction sheet has become the documentation required, thereby eliminating further searching and waste of time and resources. Upon completion of the emergency, the used copy of the appropriate annex is forwarded to the Emergency Manager for review and archiving, and a new, blank copy replaces it in the binder. The collection and collation of the used annex pages from all affected sites permits the Emergency Manager to develop a comprehensive, step-by-step, chronological narration of the entire organization’s response to the emergency, one which is very likely to be admissible in any public inquiry and which is certainly valuable for any internal review. The use of such annex “checklists” for emergency procedures is also an example of “standardized work” in order to eliminate error potential, a key feature of Six Sigma in practice. Record who made what decision when, based on what information at the time.

The role-specific Job Action Sheets can also provide a tremendous advantage in a healthcare setting. Emergencies often occur outside of normal business hours, when the majority of management staff, and presumably most of the predesignated members of the incident management team, are not on site. The site is staffed during these hours largely by staff who, while they may have large amounts of clinical experience, are untrained and inexperienced at managing most types of crises. It is a management responsibility to train staff on what to do and keep annual training records. New staff need to know if their responsibility is matched with authority. This is generally a huge problem. They don’t know what they are authorized to do and fear repercussion. Under normal circumstances, such individuals would be forced to simply do what they thought appropriate (called “freelancing”) until trained staff arrive and commence the organized response.

By placing role-specific Job Action Sheets in an annex of the Emergency Plan, it becomes possible for untrained staff to simply take those sheets, assign specific acting roles to individuals, and commence the response, well before the arrival of the predesignated staff. Armed with clear, written, step-by-step instructions, the response to the emergency should be well underway, and well documented, when the incident management team members arrive and relieve those who have filled their roles on an ad hoc basis.22 Such annexes can also serve as a useful memory aid for the predesignated members of the incident management team, particularly if they have not performed their role recently. These documents, when completed, can also be forwarded to the Emergency Manager for archiving and for collation as a part of the documentation of the incident response.

The task-specific Job Action Sheets can also provide a useful tool, particularly during the early stages of any emergency. Tasks which are important, but are only performed occasionally, may be somewhat difficult to perform accurately, particularly under the stressors associated with an emergency response. Such tasks may include, but are not limited to, the assembly of the Hospital Command Center (which may be virtual or a small team only, like an inner circle of the larger command center team) and other emergency-specific work areas, the creation of specific patientflow patterns in order to manage the emergency more effectively (e.g., suspending outpatient services, suspending elective surgery, and discharging of noncritical in-patients to provide space), placing the facility on external air exclusion to protect against an external event, locking down the facility, creating specific traffic flow and parking patterns on the property in response to an emergency, and establishing a decontamination unit, internal or external to the emergency department, so that you don’t contaminate the emergency department.

Armed with appropriate, step-by-step instructions, facility staff, including the incident management team, may perform such tasks with a reasonable degree of safety, since they are referring to a standardized, “no-deviation,” set of instructions, developed in advance, and vetted for both safety and clinical appropriateness by other members of staff or outside agencies with real expertise. To illustrate, inexperienced hospital security guards could be quite successful in modifying normal traffic flow to accommodate large numbers of ambulances, particularly if the pattern which they were implementing had been designed in advance, in consultation with local police and Emergency Medical Service (EMS).

As with other types of Job Action Sheets, all steps are documented and signed off, and the annex is simply replaced at the conclusion of the event. Once again, the use of Job Action Sheets represents a good example of the Six Sigma concept of “standardized work” as a method of reduction or outright elimination of errors and creates a level of documented response to an emergency which has never before existed in a healthcare setting. Example templates for various types of Job Action Sheets, in Microsoft Word format, are included on the web page which accompanies this book.

There is a substantial list of documents which will be required, in order to document the organization’s response to any crisis, both correctly and comprehensively. These include the various Job Action Sheets, the role and use of which has already been explained in this chapter. The list also includes a paper mechanism for the tracking of information and resource requests, normally called the information/resource request tracking form. The necessity to create a chronological log of events is addressed through the use of predesigned and printed log sheets, incorporated into their own binder. The completion of these is the responsibility of the Emergency Manager, usually assisted by a Scribe. The Scribe will also require a method for the “minute-ing” of command center meetings, and this will vary from facility to facility, based upon local policies and preferences.

The system will also require a method for reporting current status, normally called a situation report. This document, created by the Incident Manager regularly throughout the response, will be used to share current information and both progress and problems, with response partners both inside and outside of the facility. A method for capturing the information gathered through the debriefing of staff and identification of lessons learned following the event will be required, and the format of this will also be determined locally, according to both policies and preferences. Finally, the Incident Manager collates and summarizes all activities related to the event response in a final report, normally called an afteraction report and improvement plan (AAR/IP). While it is expected that such documents will normally be designed by the Emergency Manager in order to satisfy local requirements, example templates for most of these aforementioned documents, in Microsoft Word format, are included on the web page which accompany this book.

Providing Authority

An often-reported issue regarding the failure of Emergency Plans is that staff, while being able to identify which steps were supposed to take place in the response, were unsure whether or not they, as individual staff members, had the authority to implement those steps. This is hardly surprising, since many of the steps outlined in any Emergency Plan are normally beyond the scope of authority for a mid-level manager, much less a front-line staff nurse. Healthcare tends to be a cautious work environment, a necessary feature which has “spilled over” from the clinical arena. In many situations, a staff member who is unsure of what to do may do nothing other than summon help and attempt to deal with the local situation until help arrives. This response has not traditionally been discouraged in the healthcare setting, since some measures, particularly those outlined in an Emergency Plan, may actually have implications involving either finance or liability.

In writing the Emergency Plan, it is essential to ensure that the instructions are crafted in such a manner as to clarify what is to occur and to specifically empower ordinary staff to implement these measures, when it is appropriate to do so. Sometimes, the empowerment is implicit, but often it is not. To illustrate, while no one would dispute a staff member pulling a fire alarm when a fire is discovered, and common sense (it is hoped) would dictate that those patients in the immediate vicinity would be moved to immediate safety, very few would be comfortable to unilaterally decide to evacuate beyond their own floor or to evacuate to a high-risk location, such as an intensive care unit, without specific authorization. At 3 a.m., such specific authorization may not even be in the building! For this reason, it is essential for the Emergency Manager to provide preauthorized specific instructions, including the specification of who has the authority to implement each measure and a specific “trigger point” for its implementation, thereby eliminating the need for inexperienced staff members to decide whether or not the time has come for each measure. The direction must be specific; it must specifically provide authority, and it must be unequivocal in its language. To illustrate,

Upon becoming aware of a potential Mass Casualty Incident in progress, any staff member is authorized to implement the first stage of a Mass Casualty Incident response; that implementation will continue but will be reviewed and validated by the first Supervisor to arrive on site.

It is good practice to create a regular and ongoing process of review, during the creation phase of the Emergency Plan and all of its associated documents. Such review may be peer based, with the addition of “new” eyes often identifying minor errors in the text, potential areas of confusion requiring clarity, or in some cases, even outright errors. Such reviews may be conducted by one workgroup of the Emergency Preparedness Committee exchanging their work with another, or in an innovative approach, by conducting a review using “focus groups” of actual staff. An added benefit of this latter approach is the potential to foster “ownership,” and therefore, compliance, with the staff that will have to ultimately use the Emergency Plan.

In some cases, a review by subject-matter “experts” will be required. Hospitals and other healthcare organizations are complex entities, in which knowledge tends to exist in “silos,” and where no one, including the Emergency Manager, can possess a comprehensive and detailed knowledge of every operating system, whether clinical, physical, or logistical. This is particularly true in those cases in which clinical issues, building operating systems, telecommunications, or supply chains are involved. Some of these requirements are obvious. To illustrate, it is difficult to imagine creating a set of instructions for the cancellation of elective surgery, without any consultation with the chief of surgery (at minimum) and the operating room charge nurse. Similarly, one could not conceivably provide instructions to staff for the decanting of noncritical in-patients from the hospital without a specific process, approved in advance by the chief of staff and the physician community.

With respect to the physical plant of the hospital, no one understands the operating systems better than the chief engineer; he or she knows specifically what hospital systems can and cannot do, and what the result of any changes to these systems is likely to be. It is essential to access that knowledge through the review process, in order to avoid providing instructions to staff which simply may not work and, in some cases, might even fail catastrophically, if mismanaged. Similar situations also exist for both telecommunications and even supply chain issues. There is little point in providing even the incident management team staff with instructions to contact a particular supplier for a service, if 24-hour contact arrangements with that supplier are not already in place.

Obtaining Approvals

Almost all elements of any Emergency Plan possess the potential for serious implications for the organization which they protect, if used incorrectly or if the information contained is incorrect. The Emergency Plan is intended to provide instructions that are aimed at protecting patients, staff, and the organization against any type of error, which could occur during any emergency. In order to do so, those instructions must be compliant with best practices, policy, and the law and must be performed correctly and must be fully validated, prior to its introduction or use.

From the perspective of potential liability, it is essential that all elements of the Emergency Plan be reviewed by, and approved by, the Senior Management Team of the organization, prior to implementation. In some organizations, this may simply involve providing the opportunity to read over the completed document in “draft” form and to offer both factual corrections and suggestions for improvement. In other organizations, it may actually involve a process of presentations to the senior team by the Emergency Manager. Finally, it may involve the need for a review by corporate legal counsel, in order to ensure compliance with both laws and regulations. Get stakeholder feedback; ask people if it works? Does it make sense? Is this how we operate? Integrate the feedback. Do a structured walk-through of your plan’s concepts. List the strategic decisions that management has to make and build into the plan (outline the impacts).

In all cases, the entire approval process must be meticulously documented by the Emergency Manager. The dates of delivery and return of the entire document, or sections of the document, who they were delivered to, and what specific feedback was provided must be included in the documentation. Any discussions, including telephone conversations, should be documented, and any meetings should be minuted. The contents of any presentations to senior staff should also be archived. By doing so, the process for the review and approval of the Emergency Plan remains completely transparent and very difficult to criticize in any future public inquiry or other legal action.

In all cases, the review and consultation process should be meticulously documented. Records must be maintained of every review process, every discussion, and every meeting. All correspondence regarding this review process should also be archived by the Emergency Manager. These measures provide a necessary and complete transparency in the plan creation process. It is also not uncommon for the etiology of a particular element of instructions or work direction to become the subject of discussion at any future public inquiry or other legal action. When such documentation is absent and cannot be introduced, the process of creation of the instruction or work direction can potentially become the subject of speculation—an entirely undesirable outcome which good documentation prevents. Give people electronic copies. Put EM manuals in strategic locations for easy access during an emergency. Create an Emergencies Cart—with the plan and emergency supplies—and locate these manuals throughout the facility. Develop and have in place a system with which staff will easily know which rooms have already been evacuated.

Conclusion

The information included in this chapter, including both the proposed sections and the approach to the structuring and provision of access to information, is innovative. While the sections include some of the best features of older-style Emergency Plans, some elements are completely new to emergency preparedness in healthcare settings. The incorporation of essential principles of mainstream management practices such as Lean, Six Sigma, and Project Management is intended to create a document which is better understood and, therefore, more valued by the management team than has traditionally been the case. The ease-of-use features, including making information easy to find and providing instructions which are immediately clear and straightforward, will also ensure that front-line staff value and use the plan, rather than “freelancing” because they cannot easily find the information that they need. The practices outlined in this chapter should also provide the healthcare-based Emergency Manager with increased credibility among the management team of the hospital or other healthcare organization, and among front-line healthcare staff in general.

Student Project #1

Select a single adverse event with a potential to occur within a healthcare setting. Research the nature of the event appropriately and identify any critical systems which would be affected by the event. Consult with those responsible for the critical systems in question, in order to fully understand the impacts and the response requirements. Now create a checklist tool to respond to this event, for use by a new manager with minimal familiarity with the building or the systems in question. Create a report to accompany the checklist, describing the process of creation and the process of consultation and citing the appropriate references, in order to demonstrate that the appropriate research and consultation have occurred.

Student Project #2

Select a single, emergency-specific resource, such as the Hospital Command Center, the media information center, the family information center, and staff staging area, which is not normally in operation within the facility. Review in detail the process for the creation of that resource, including primary and backup locations, physical layout, resource requirements, staffing, and activation procedures. Now create a step-by-step checklist for the activation of that resource for use by a new manager with minimal familiarity with the building and its operating systems. Ensure that you include specific detail on the location of all required resources, and how to obtain their use, including access outside of normal business hours. Create a report to accompany the checklist, describing the process of creation and the process of consultation and citing the appropriate references, in order to demonstrate that the appropriate research and consultation have occurred.

Test Your Knowledge

Take your time. Read each question carefully and select the most correct answer for each. The correct answers appear at the end of the section. If you score less than 80 percent (8 correct answers) you should reread this chapter.

1. A segment of the Emergency Plan which contains case-specific instructions for dealing with a specific type of emergency is called:

(a) The main body

(b) An appendix

(c) A Job Action Sheet

(d) An annex

2. A segment of the Emergency Plan which contains information which is not for general distribution, such as home telephone numbers for senior staff, is called:

(a) The main body

(b) An appendix

(c) A Job Action Sheet

(d) An annex

3. A segment of the Emergency Plan which contains specific instructions for the activation of a Key Role position or for the assembly of an emergency-specific resource, such as the command center, is called:

(a) The main body

(b) An appendix

(c) A Job Action Sheet

(d) An annex

4. A formal statement outlining the scope of the Emergency Plan, describing the legal authority for the plan, or outlining authority to activate the Emergency Plan, would be contained in:

(a) The main body

(b) An appendix

(c) A Job Action Sheet

(d) An annex

5. A critical principle of Emergency Plan design which reflects the philosophy of the Lean for Healthcare system is:

(a) Ease of access to information for the user

(b) Keeping language simple for the user

(c) Standardizing work for the user

(d) Both (b) and (c)

6. Six Sigma is a management system which is primarily designed to:

(a) Define responsibilities

(b) Eliminate errors wherever possible

(c) Define legal responsibilities

(d) Reduce the number of plan copies in circulation

7. The widespread use of comprehensive checklists in the Emergency Plan is an application of the Six Sigma principle of:

(a) Providing clear instructions

(b) Comprehensive simplicity

(c) Standardized work

(d) High-quality documentation

8. One of the strengths of the Job Action Sheet in an Emergency Plan for a healthcare setting is the ability for staff with minimal training to begin to activate the Emergency Plan:

(a) Outside of normal business hours

(b) When specially trained staff are not immediately available

(c) During the business day when leaders are busy

(d) Both (a) and (b)

9. The segment of the Emergency Plan which clearly defines what the plan is intended to be used for and what it is not intended to be used for is called the:

(a) Statement of scope

(b) Statement of authority

(c) Authority to activate statement

(d) Spending authority statement

10. In order to be considered current in most jurisdictions, an Emergency Plan document should be reviewed following each emergency event or exercise, and revised at least:

(a) Every six months

(b) Annually

(c) Every two years

(d) Every five years

Answers

1. (d)

2. (b)

3. (c)

4. (a)

5. (a)

6. (b)

7. (c)

8. (d)

9. (a)

10. (c)

Additional Reading

The author recommends the following exceptionally good titles as supplemental readings, which will help to enhance the student’s knowledge of those topics covered in this chapter:

Hospital Emergency Operations Plan. 2013. New York, NY: University Hospital of Brooklyn, .pdf document. http://training.fema.gov/EMIWeb/edu/docs/nimsc2/NIMS%20-%20Lab%2010%20-%20Handout%2010-13-Hospital%20EOP.pdf (accessed January 31, 2014).

Rittman, S.J., K.I. Shoaf, and A. Dorian. 2005. Writing A Disaster Plan: A Guide For Health Departments. UCLA Centre for Public Health and Disasters, .pdf document. ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/phlpprep/Legal%20Preparedness%20for% 20Pandemic%20Flu/8.0%20-%20Non-Governmental%20Materials/8.6%20Writing%20a%20Disaster%20Plan%20-%20UCLA.pdf (accessed January 31, 2014).

Shirley, D. 2011. Project Management for Healthcare. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Sorensen, B.S., R.D. Zane, B.E. Wante, M.B. Rao, M. Bortolin, and G. Rockenschaub. 2011. Hospital Emergency Response Checklist: An All-Hazards Tool for Hospital Administrators and Emergency Managers. World Health Organization, .pdf document. www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/148214/e95978.pdf (accessed January 31, 2014).