1

Social-emotional Competencies and Learning in Children

Ophélie COURBET and Thomas VILLEMONTEIX

LPN, Université Paris 8 Vincennes-Saint-Denis, France

This chapter focuses on the interactions between social-emotional competencies and learning in preschool and school-aged children. More specifically, it aims to present the concept of social-emotional competencies and to explain the influence of these competencies in the short-term on the child’s success in school learning, as well as in the long-term on his or her quality of life and socio-professional integration. The mechanisms that determine the reciprocal association between social-emotional competencies and learning are then explored. Finally, this chapter will look at programs that enable students to learn social-emotional competencies at school, through examples of international programs, and will detail the benefits associated with this type of learning.

1.1. Social-emotional competencies, a key predictor of child development

1.1.1. Definitions

Learning and succeeding at school does not depend on intellectual skills alone. Children learn and grow in a community, in situations and through human relationships that inevitably include an emotional dimension. Over the past two decades, multiple research studies have enabled us to better identify the skills that help children adapt to such an environment and, by extension, to acquire academic knowledge and skills. Social-emotional competencies (SECs) refer, as their name indicates, to a set of fundamental skills related to the emotional and relational spheres of life. They can be divided into five categories: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills and responsible decision-making (Durlak et al. 2011). Depending on the study, there are differences in the way they are defined, but the following box is a summary of the definitions found in the literature (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning and National Center for Mental Health 2008; O’Conner et al. 2017).

SECs are partly underpinned at the cognitive level by executive functions, a set of mechanisms that allow the individual to direct their behaviors in a way that achieves their goal, in line with the characteristics and demands of the environment (Jacob and Parkinson 2015; O’Conner et al. 2017). Three fundamental executive functions are distinguished (Diamond 2013):

- – Inhibition: this refers to the ability to control attention (resist distractors), behavior and emotions.

- – Updating working memory: this is the ability to retain information in memory and to manipulate it mentally. It enables, for example, remembering instructions, planning an action and considering alternatives, updating the information we have on a situation and, finally, reasoning and making decisions.

- – Cognitive flexibility: this reflects the ability to change perspective. This allows us, for example, to take the perspective of others, to adjust to the demands of a changing environment, or to change our strategy to solve a problem.

The sound development of these executive functions has an impact on SECs (O’Conner et al. 2017).

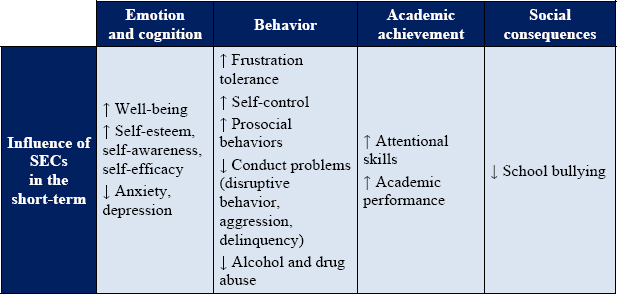

1.1.2. Influence of short-term SECs: emotion, behavior and academic achievement

Young children with behavioral problems also tend to have deficits in SECs (Bierman and Welch 1997). For example, good self-regulatory skills are associated with lower levels of child behavior problems, while lower levels of self-regulation are associated with the presence of externalized behaviors such as aggression (Baron et al. 2017; O’Conner et al. 2017). Self-regulation skills at the age 4 years (measured by a child’s ability to withstand a delay in obtaining a reward) predict attentional skills, self-control and frustration tolerance later in adolescence (Shoda et al. 1990), three constructs linked to problem behavior. Lack of these skills is also associated with peer rejection (Schultz et al. 2001; Marryat et al. 2014). Finally, low levels of self-regulation are associated with poorer attention span and diminished academic achievement (Baron et al. 2017).

However, SECs seem to be unevenly distributed among students, and particularly deficient in some of them. For example, in the results of a Canadian study seeking to identify different profiles of social-emotional functioning in kindergarten students (Thomson et al. 2019), a majority of children (approximately 60%) had above-average scores in all areas of social-emotional functioning, while the remaining 40% had below-average scores in at least one of the areas assessed. Of these 40% of students, 3% had scores one standard deviation below the mean in all of the areas of social-emotional functioning assessed, indicating the presence of a group with significant difficulty in this area. The same type of finding is observed from kindergarten onward by teachers: in a study in Scotland, teachers reported, through standardized questionnaires, that 13% of their pupils had a deficit in prosocial behaviors and 8% had difficulties in their relationships with peers (isolation, bullying) (Marryat et al. 2014), and in the United States, 20% of teachers responding to a national survey estimated that more than half of their pupils lacked certain social skills (Rimm-Kaufman et al. 2000).

Table 1.1. Influence of short-term SECs on different domains (emotion and cognition, behavior, school achievement and social consequences). The up arrow corresponds to an increase in the average scores for the variable mentioned and the down arrow to a decrease. (Sources: Data from Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning and National Center for Mental Health 2008; Durlak et al. 2011; Bonell et al. 2018)

Because of this disparity in students’ mastery of SECs, some research has examined whether they can be taught and the impact of such learning. The learning of these SECs is known as social and emotional learning (SEL).

In particular, a 2011 meta-analysis drew on 213 social and emotional learning programs, targeting at least one SEC and having at least part of the program integrated into compulsory school hours (other parts targeting, for example, parents to work on SECs with their child or the whole school to support SEC teaching in all school environments). These programs were aimed at students from kindergarten to high school, mostly in the United States, and were delivered by teachers or outside speakers (Durlak et al. 2011) (for a description of some of the programs, see section 1.3.3). This meta-analysis showed that this type of program significantly improved targeted SECs, students’ relationship with self (in terms of self-esteem, self-concept and feelings of self-efficacy), with others and with school, as well as their academic performance in terms of grades and test scores (Durlak et al. 2011). Students’ behavioral adjustment was also better after the intervention, with an increase in prosocial behaviors and a decrease in conduct problems (such as disruptive behavior in class, aggression or delinquent acts) and internalized problems (anxiety and depression). However, these effects tended to diminish over time but remained significant overall at least six months after the end of the intervention. It has also been shown that social and emotional learning programs, whether developed in school, outside of school or for families, significantly reduce the level of anxiety and depression, the level of disruptive behaviors such as rule breaking and aggression, and alcohol and drug abuse in children and adolescents (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning and National Center for Mental Health 2008).

Finally, the promotion of SECs has an impact on the issue of bullying. For example, an intervention program (Learning Together) recently focused on three aspects: the development of SECs, restorative practices aimed at improving communication between the aggressor and the victim of violence, and conflict resolution within the classroom. This intervention showed small but significant effects in decreasing reported bullying in middle and high school (Bonell et al. 2018). In addition, the intervention appears to have had the most effect on students who were experiencing higher level of bullying, and it had beneficial effects on other variables such as well-being, quality of life and substance use, the latter of which can be seen as a marker of academic disengagement. In contrast, it did not appear to have an effect on the level of aggression between students (Bonell et al. 2018).

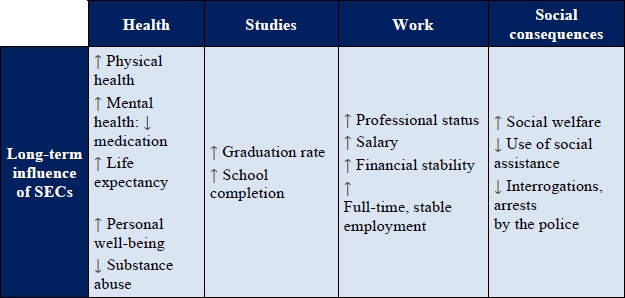

1.1.3. Long-term influence of SECs: quality of life and socioprofessional integration

In the long-term, SECs have a positive influence on health and life expectancy, occupational status and salary, and social and personal well-being (OECD, 2015). A longitudinal study of a population from a disadvantaged socio-economic background in the United States over a period of 19 years looked in particular at kindergarten teachers’ assessment of children’s prosocial and self-regulation skills and their association over time with various outcomes (Jones et al. 2015). It showed that these teacher-rated skills were significantly associated over time with educational, employment, criminal activity, substance use and mental health outcomes in adolescents and young adults. These associations over time remained significant even when controlling for variables such as the socio-economic characteristics of the child’s family, the child’s aggressive behaviors and primary academic skills, and other contextual factors (Jones et al. 2015). Specifically, the child’s social interaction and self-regulation skills were predictive of obtaining a high-school diploma on time, a college degree and stable, full-time employment. These were inversely predictive of use of social assistance such as public housing, involvement with law enforcement, having ever been arrested or taken into custody, substance abuse and being on medication for an emotional or behavioral problem during the high school years (Jones et al. 2015). Another longitudinal study found that good self-regulatory skills in childhood predict good health, financial stability and educational completion in adulthood (Moffitt et al. 2011). On the contrary, low self-regulatory abilities are also associated in the longer term with poorer health and greater financial difficulties (Durlak et al. 2011; Baron et al. 2017). In terms of health, SECs (and in particular self-regulatory capacity) are inherently linked to mental health (see Thomson et al. (2019) for more details on the specificity of the associations between certain SEC profiles in childhood and different mental disorders in adolescence), but they are also linked to physical health: indeed, these are associated with the development of “healthy” behaviors (Durlak et al. 2011; Baron et al. 2017; OECD 2015).

Thus, developing SEL seems to be a promising approach to increasing children’s academic and socio-economic success. However, despite their importance in many areas of a child’s life, SECs are currently rarely taught explicitly in schools in France.

Table 1.2. Influence of long-term SECs on different domains (health, education, work, social consequences). (Sources: Data from Durlak et al. (2011), Moffitt et al. (2011), Jones et al. (2015), Baron et al. (2017) and OECD 2015)

1.2. Mechanisms underlying the association between SECs and learning

1.2.1. Influence of the child’s social-emotional characteristics on their learning abilities

Learning processes are not emotionally neutral processes: they involve motivational engagement and elicit emotional responses, positive or negative. They also take place in a social and relational context, which the child may or may not be able to rely on. For these reasons, learning processes are directly dependent on the individual’s SECs. For example, low self-regulatory skills interfere negatively with the ability to stay focused on the activity at hand, to participate in classroom activities and to concentrate on the task at hand (Barkley 2001); students who are self-aware and confident in their learning abilities will tend to persist and try longer when faced with a difficult task than those who lack self-awareness and confidence in their abilities, thus increasing their chances of success. Students who know how to set high goals, self-discipline, motivate themselves, manage stress and organize themselves will learn more and get better grades (Durlak et al. 2011). Also, having problem-solving skills is helpful in the learning context, as it allows for overcoming difficulties and making responsible decisions about doing homework, for example, allowing for greater academic success. Finally, better SECs may allow the child to better rely on cooperation with the teacher or peers to successfully complete proposed tasks (Baron et al. 2017).

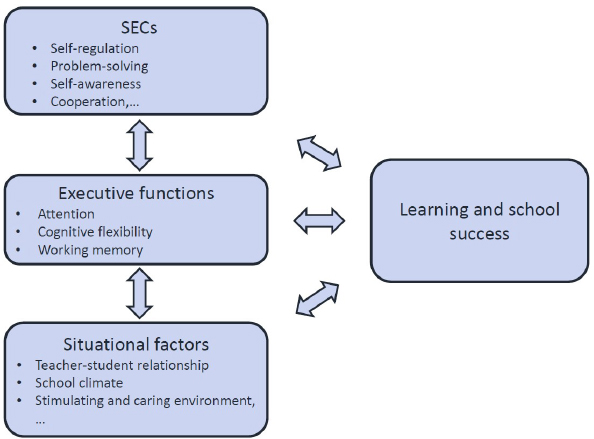

This is the same link mentioned earlier between SECs and executive functions. The ability to direct one’s behavior toward a goal, which is the role of executive functions, is a key component of success in many academic tasks, and some studies report that students with poor executive abilities tend to perform poorly at school (Jacob and Parkinson 2015). Conversely, good SECs thus promote optimal executive functioning. Indeed, evidence suggests that social and emotional learning programs have an impact on certain executive functions, such as inhibitory control, planning and flexibility (Durlak et al. 2011). Self-regulatory capacity seems particularly important: for example, an interventional study evaluating the impact of a kindergarten SECs development program, the Chicago School Readiness Project, showed that the effects of this program on improving academic skills (vocabulary, letter naming and early math skills) are mediated through improvements in children’s self-regulation (Jones et al. 2013).

While poor SECs directly and negatively influence learning processes, they make it more likely that the child will develop behavioral problems. Opposition to the teacher’s requests in class, failure to follow rules, inability to regulate behavior to meet the various expectations of class life, conflicts with the teacher or with classmates in the classroom, school yard or with parents at homework time, will interfere with the child’s learning.

From an attentional point of view, emotional problems (anger, frustration and anxiety) associated with these conflictual situations can divert the child’s attention from the content of school learning. Brain imaging research suggests that content with an emotional dimension is processed in a preferential way on the attentional level, and this in an automated way (Vuilleumier et al. 2005). If the child fails to regulate this processing, it will cause an emotional distraction that interferes with the cognitive functioning expected in class (Iordan et al. 2013). In particular, when negative or positive emotion is too strong, the individual’s attention becomes less flexible, their behaviors are more persistent, their higher order thinking skills are impaired and they respond to stimuli in a more reactive and less reflective manner, which can significantly impair ongoing learning (Arnsten 2000). From a motivational point of view, the repetition of failure situations or negative comments related to schooling due to behavioral problems can lead to the learning of an association between school tasks or environment and negative emotions. This learning will lead to avoidance behaviors in the child, who may then refuse to do school work at home or be reluctant to go to school. Thus, the occurrence of behavioral problems will also have an impact on the learning process, and therefore in the medium-term on the child’s academic performance.

1.2.2. Influence of the social-emotional environment on the child’s learning processes

In addition to these explanations focused on the student’s personal characteristics, there are explanations focused on the student’s environment, relationships and instructional characteristics. Self-regulation, for example, is the product of the integration of biological and behavioral processes that are shaped by the child’s background (Blair and Raver 2015). Some studies show that academic performance can be enhanced by having academic achievement valued and supported by the child’s adults and peers. Academic achievement can also benefit from practicing more child-engaging instruction, including cooperative learning, a safe and orderly classroom environment that encourages and reinforces the child’s positive classroom behaviors, and having good student-teacher relationships that foster the child’s engagement and attachment to school (Durlak et al. 2011). For example, a poor school climate can negatively influence a child’s ability to learn, which in turn influences the child’s engagement in school, effort – and therefore performance.

Regarding the teacher-child relationship, the previously cited study on the effects of the Chicago School Readiness Project found that the effect of this intervention program on children’s academic performance and behavior was due to a better quality of the teacher-child relationship, that is a closer, warmer, emotionally positive and less conflictual relationship, which in turn impacted the child’s self-regulation. Better regulation would then in turn impact on their academic performance, behavior and emotional adjustment (Jones et al. 2013; Blair and Raver 2015). The development of a good quality teacher-child relationship at school is particularly important for children from low-income families, who may experience greater instability in their other living environments (Silver et al. 2005). In addition, it is noted that children who are engaged in a conflictual relationship with their teachers develop more negative attributions about the teacher’s ability to be a trustworthy source of support, as well as about their own learning abilities (Hamre and Pianta 2005, cited by Jones et al. 2013). Finally, longitudinal analyses have shown that a teacher’s perception of the quality of their relationship with a student (close versus conflicted) accounts for a small but significant portion of the variance in the child’s academic skills later on, even after the child’s baseline academic skills have been controlled for (Blair and Raver 2015). These effects on learning can be explained by the fact that a poor quality of the teacher-child relationship causes detectable stress via endogenous cortisol levels, which affects the child’s emotional regulation capacity and executive functioning of the child (Blair and Raver 2015). With regard to executive functioning, in particular, a conflictual relationship between child and teacher in kindergarten results in poorer development of the child’s working (visuospatial) memory over time, whether assessed toward the end of the school year or the following year with a change in teacher (De Wilde et al. 2016).

1.2.3. SECs and the learning context: a reciprocal influence

The last 20 years of research has highlighted that not only are the child’s SECs shaped by their experiences of classroom life, but also that the students’ SECs themselves shape those experiences. Thus, there is a reciprocal influence between SECs and school learning contexts (Blair and Raver 2015).

Figure 1.1. Reciprocal influences between social-emotional competencies (SECs), executive functions, situational factors, as well as learning capacity and academic achievement (Sources: Durlak et al. 2011; Jones et al. 2013; Blair and Raver 2015; De Wilde et al. 2016; Baron et al. 2017; O’Conner et al. 2017)

Thus, the creation of a physically and psychologically safe and stimulating learning environment, with calm and loving teacher-student relationships, will enable children to develop their SECs, especially if these are explicitly learned. In turn, children with better SECs will show better self-regulation, be more attentive to others, be more responsible and consequently have better relationships with each other and with the teacher. They will be less likely to disrupt the learning of others and will be more likely to adopt the prosocial and achievement-oriented norms promoted by the school. All of this, in turn, will contribute to a calm, supportive and learning-focused learning climate. There are thus positive reinforcement processes between positive school contexts and individual children’s SECs, in a dynamic of reciprocal reinforcement over time. This positive dynamic leads to greater attachment to the school and a reduction in emotional difficulties and behavioral problems, which in the long-term promotes the child’s motivation to study and academic performance (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning and National Center for Mental Health 2008).

1.3. Working with SECs in learning

1.3.1. The school as a place to promote SECs

SECs have an influence on many areas of a child’s life, as well as on the child’s future: developing them is therefore a major challenge. Importantly, the acquisition and command of SECs are dependent on situational factors and their level of command can be modulated through formal and/or informal learning throughout the child’s life (OECD 2015). The school, as a favorable context for learning in a social context, can therefore be a favorable context for learning these skills. Interventions aimed at developing SECs are best carried out from the child’s first years at school.

Indeed, over time, the gap between students in terms of SECs widens: small differences between students in terms of self-regulatory abilities in the early years of school, for example, will tend to increase over time, leading to large differences between students who did not have the same abilities at the start (Baron et al. 2017). This is particularly significant when one considers that not all children start out with the same foundation: those from disadvantaged backgrounds have, on average, more problems with self-regulation (Blair and Raver 2015).

In schools, learning devices for these skills can be implemented from kindergarten through high school. Their goal is to teach SECs by modeling desired behaviors, coaching students to practice them and helping them apply their learning in different everyday situations until students integrate them as part of their behavioral repertoire (Durlak et al. 2011).

Some programs also use SECs to help students prevent problems such as violence, bullying, substance abuse or academic failure (Durlak et al. 2011). These programs are geared toward both reducing problem behaviors and improving child development.

Box 1.2. Examples of the type of content of social and emotional learning sessions

1.3.2. Important elements for the implementation of programs in schools

It is important to note that these programs must be properly implemented to be effective: for example, they become less effective if teachers do not complete the intervention, or if it is conducted by someone who is not adequately trained (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning and National Center for Mental Health 2008). Indeed, trained teachers are more likely to complete all of the lessons in the program and to conduct them in a manner that is true to the intent of its developers (O’Conner et al. 2017). Similarly, interventions appear to have effectiveness across all desired domains only if they are offered by teachers within the school, as opposed to outside speakers.

Furthermore, these interventions generally have a greater impact when they share certain characteristics:

- – Sequenced and coordinated tasks that allow for step-by-step development of SECs. For example, the child may first learn to identify and name different emotions, then learn to identify their effects within himself or herself, and finally practice putting themselves in another’s shoes by understanding their feelings.

- – Active and dynamic forms of learning, through role-playing or rehearsals that allow students to practice these skills directly. Thus, the regulation of one’s emotions can be learned through relaxation exercises practiced in class, or conflict resolution through workshops in which children are encouraged to express their personal feelings about the situation, to verbalize their emotions and to listen to each other, by repeating, for example, what the other has just expressed as a feeling.

- – A focus on social and emotional learning. The goal of each session is to participate in the development of at least one of the SECs.

- – Activities based on a theoretical model of social and emotional learning that explicitly target SECs through the development of learning objectives and direct instruction. The objectives of the sessions are always made explicit to the child in an age-appropriate way – “It will help us show our friends that we care about them1”. The benefits of each session are made explicit and the learning from previous sessions is worth repeating – “Last week we talked a lot about being mindful of our emotions/feelings. Emotions can feel good or not so good. Emotions change all the time, and we can take care of our emotions by being kind to them”.

A classroom climate that fosters care and safety for students also helps to stimulate this learning (O’Conner et al. 2017).

To maximize fidelity to the program during implementation in schools, it is best to provide standardized manuals with lesson plans and necessary materials for teachers, a standardized teacher training program implemented by qualified coaches, initial training that presents the theoretical models on which the program is based, the activities and expected effects, adaptation to the cultural and social context of the children, and ongoing support with follow-up and training for teachers as well as feedback on the activities they conduct (O’Conner et al. 2017).

However, further research is needed to determine which elements of an intervention program can be adapted to the context without altering its content and which should be implemented as is.

Finally, longer, multi-year programs are more effective than shorter ones: the skills acquired in the early years provide a foundation for skill development in later years. They are also more effective when practiced in multiple settings, such as the classroom, the playground and the home (O’Conner et al. 2017): for this reason, it is recommended that SEC development programs be fully integrated into school practices and involve teachers, school administrators and parents who can reinforce social and emotional learning at home as much as possible (O’Conner et al. 2017). Moreover, the overall effects of SEC development programs potentially take time to develop and thus become visible, and the implementation itself within the school takes time to be fully in place (Bonell et al. 2018): thus, interventions would benefit from being continued over several years of the child’s schooling to be reinforced.

1.3.3. Some international social and emotional learning programs

Numerous programs aimed at developing SECs in students from kindergarten through high school have been implemented and evaluated, particularly in the United States. The meta-analysis by Durlak et al. (2011) is based on 213 evaluation studies of this type of program. These studies were found to result in an improvement in the SECs in question, and also in academic performance, as well as a reduction in behavioral problems. All of these effects are statistically significant six months after the intervention (Durlak et al. 2011). However, this meta-analysis does not find any additional benefit of programs offered in multiple contexts compared to those implemented only in the classroom, contrary to recommendations presented in other literature reviews (see in particular Greenberg et al. 2001).

However, this may be due to the fact that implementing such a program in multiple contexts, with the involvement of families or the whole school for example, is more likely to lead to implementation problems (Durlak et al. 2011).

The Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (PATHS) program is one that has undergone multiple evaluations. In particular, it focuses on attention to one’s own and others’ emotions and seeks to encourage children’s self-regulatory skills rather than modifying their behaviors (Domitrovich et al. 2007). It is based on the ABCD (Affective Behavioral Cognitive Dynamics) developmental model, which promotes understanding of emotions, thoughts and behaviors in relation to SECs. For kindergarteners, it includes lessons on communicating positive emotions, different emotions, self-regulation and problem solving, with the aim of developing (1) recognition of one’s own and others’ emotions, (2) control of one’s emotions and behavior, (3) promotion of positive self-awareness and peer relationships, (4) problem solving and (5) creation of a positive classroom climate (Domitrovich et al. 2007).

The Tools of the Mind program, on the other hand, relies on the implementation of role-playing (preparing the script, choosing actors and performing the chosen scene) and collaborative school activities (e.g. reading a book aloud in pairs by alternating roles) (Baron et al. 2017) (see also Chapter 6).

Chicago School Readiness is a program that aims to improve preschoolers’ self-regulation skills through the development of positive teacher-student relationships and improved teacher classroom management to prepare them for entry into elementary school socially-emotionally and academically (Jones et al. 2013; Jacob and Parkinson 2015).

Finally, the Kindness Curriculum incorporates mindfulness meditation. The objective is to develop the child’s self-regulation and prosocial skills (Flook et al. 2015). Indeed, mindfulness meditation improves emotional regulation as well as attention and executive functioning, by exercising the ability to pay attention to a particular object, be it breathing, external stimuli, one’s thoughts or emotions, to detect one’s attentional disconnections (self-monitoring) and to refocus one’s attention on the chosen object (cognitive flexibility) (Flook et al. 2015). Alongside the mindfulness exercises, activities focusing on empathy, gratitude, sharing and caring are proposed and adapted to the child’s age.

1.3.4. Effects of learning SECs at school

The PATHS social and emotional learning program seems to be particularly interesting for supporting children’s academic learning in elementary school. Indeed, students who have benefited from this program have a higher level of reading, writing and mathematics than students who have benefited from a program based on no more than a few SECs, at a given grade level, and more particularly among students from a low socio-economic background (Schonfeld et al. 2015). A randomized trial of low-income preschool children showed that children who received the program had more knowledge of emotion vocabulary, were better ability to identify emotions and less bias in identifying ambiguous emotions as anger than children who did not receive the program (i.e. who were on a waiting list). They were also more able to self-regulate, less socially withdrawn and more socially competent, according to their parents and teachers (they initiated more social interactions, had better emotional regulation and better social skills with peers) (Domitrovich et al. 2007). These effects were visible after 1 year of teaching.

However, this program does not seem to have an impact on social problem solving and externalizing behaviors assessed by parents and teachers in this age group, and students with poorer language skills do not see an increase in their level of cooperation with peers compared to those in the control group: thus, it might be useful to develop language skills in parallel with SECs to obtain better results on the development of SECs (Domitrovich et al. 2007). In elementary school, the effects on prosocial behaviors are also found. However, contrary to the previous results, a reduction in the level of aggression was observed, which was more pronounced among students who had the highest levels of aggression at the beginning (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group 2010). However, the effects of the program on the level of acceptance of teacher authority, pupil concentration and social skills were found to be lower in the most socio-economically disadvantaged schools, which the authors explain as a result of higher pupil and teacher turnover, making implementation difficult (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group 2010).

The effectiveness of the Tools of the Mind program, on the other hand, taking into account the results of various studies and randomized controlled trials, seems limited on cognitive functions, and only an improvement in students’ math skills could be noted. Literature and self-regulation skills were also not significantly improved (Baron et al. 2017). According to another randomized controlled trial, however, this program does reduce school behavior problems (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning 2012).

The Chicago School Readiness Program has been shown to be effective in improving classroom climate, teacher responsiveness, management of classroom behavior problems, as well as the child’s executive functioning (including inhibition skills and attention) and self-regulation, level of externalized and internalized problems and the child’s emerging academic skills (such as letter naming ability and early math skills) (Raver et al. (2009, 2011) as cited in Jones et al. (2013) and Jacob and Parkinson (2015)). The latter effect was mediated by improvements in response inhibition and attention skills (Jacob and Parkinson 2015). Effects on executive functioning and academic achievement were sustained over the long-term (up to 10–11 years after the end of the program), whereas outcomes on behavioral problems did not appear to be sustained over time (Watts et al. 2018). Children who participated in the program also reportedly had increased sensitivity and reactivity to emotional stimuli (faces) evoking sadness and anger, but this did not translate to behavioral outcomes: they did not show more emotional and behavioral dysregulation in response to this overactivity (Watts et al. 2018).

Finally, according to a randomized controlled trial, kindergarten children who received the Kindness Curriculum made more progress in social skills (assessed by the teacher and a behavioral sharing task) and scored higher on teacher assessments of learning, health and emotional development, while the control group (wait-listed to receive the intervention) showed increased selfish behavior (less sharing) over time (Flook et al. 2015). In addition, there was a small to moderate effect of the program on students’ cognitive flexibility and tolerance for waiting for a reward (indicative of their ability to self-regulate), but no specific effect on inhibitory control (Flook et al. 2015). Importantly, it can be emphasized that children’s baseline level mediates the impact of the program: children with worse social skills and executive functioning at baseline gain more skills over the course of the intervention compared to the control group (Flook et al. 2015).

1.3.5. Current limitations in the field of SEC development in schools

Among the main limitations of the study of SECs is the lack of rigorous definition of certain constructs: for example, concepts of self-regulation are not always defined in the same way, and the same is true for SECs. These are not always defined or classified in the same way. The assessment of SECs also lacks standardized measures at the moment (Durlak et al. 2011).

In addition, there are few studies evaluating programs that specifically target students with pre-existing behavioral or emotional problems or academic difficulties. Also, while it is certainly more useful for child development to combine the five SECs in intervention programs, it would be interesting to examine the relative contributions of the different SECs on the developmental parameters assessed, and to determine which specific skill or combination of skills specifically affects which parameter at different levels of child development (Durlak et al. 2011). It would also be interesting to further assess the moderators of the effects of these SEC development programs.

Finally, in order to ensure continuity of social and emotional learning in the child’s various living environments, it would be interesting to develop more programs that include intervention modules for parents in addition to intervention in the school setting.

1.4. References

Arnsten AF. (2000). Stress impairs prefrontal cortical function in rats and monkeys: Role of dopamine D1 and norepinephrine alpha-1 receptor mechanisms. Prog. Brain Res., 126, 183–192.

Barkley, R.A. (2001). The executive functions and self-regulation: An evolutionary neuropsychological perspective. Neuropsychology Review, 11, 1–29.

Baron, A., Evangelou, M., Malmberg, L.-E., Melendez-Torres, G.J. (2017). The tools of the mind curriculum for improving selfregulation in early childhood: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Review, 13(1), 1–77.

Bierman, K.L. and Welsh, J.A. (1997). Social relationship deficits. In Assessment of Childhood Disorders, Mash, E.J., Terdal, L.G. (eds). Guilford Press, New York.

Blair, C.B. and Raver, C.C. (2015). School readiness and self-regulation: A developmental psychobiological approach. Annu. Rev. Psychol., 66, 711–731.

Bonell, C., Allen, E., Warren, E., Fletcher, A., Sadique, Z., Elbourne, D., Christie, D., Bond, L., Scott, S., Viner, R.M. (2018). Effects of the learning together intervention on bullying and aggression in English secondary schools (inclusive): A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 392(10163), 2452–2464.

Centre national d’étude des systèmes scolaires (Cnesco) (n.d.). Zoom sur le développement de compétences sociales et émotionnelles des élèves [Online]. Available at: www.cnesco.fr/fr/qualite-vie-ecole/competences-sociales-et-emotionnelles-des-eleves.

Chernyshenko, O.S., Kankaraš, M., Drasgow, F. (2018). Social and emotional skills for student success and well-being: Conceptual framework for the OECD study on social and emotional skills. OECD Education Working Papers No. 173, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (2012). Effective Social and Emotional Learning Programs: Preschool and Elementary School Edition. Guide, Chicago.

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning and National Center for Mental Health (2008). Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) and Student Benefits: Implications for the Safe Schools/Healthy Students Core Elements. Report, Education Development Center, Chicago.

Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group (2010). The effects of a multiyear universal social–emotional learning program: The role of student and school characteristics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 156–168.

De Wilde, A., Koot, H.M., Van Lier, P.A.C. (2016). Developmental links between children’s working memory and their social relations with teachers and peers in the early school years. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol., 44, 19–30.

Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annu. Rev. Psychol., 64, 135–168.

Domitrovich, C.E., Cortes, R.C., Greenberg, M.T. (2007). Improving young children’s social and emotional competence: A randomized trial of the preschool “PATHS” curriculum. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 28(2), 67–91.

Durlak, J.A., Weissberg, R.P., Dymnicki, A.B., Taylor, R.D., Schellinger, K.B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432.

Flook, L., Goldberg, S.B., Pinger, L., Davidson, R.J. (2015). Promoting prosocial behavior and self-regulatory skills in preschool children through a mindfulness-based kindness curriculum. Developmental Psychology, 51(1), 44–51.

Greenberg, M.T., Domitrovich, C.E., Bumbarger, B. (2001). The prevention of mental disorders in school-aged children: Current state of the field. Prevention & Treatment, 4(1), 1–62.

Huaqing Qi, C. and Kaiser, A.P. (2003). Behavior problems of preschool children from low-income families: Review of the literature. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 23(4), 188–216.

Iordan, A.D., Dolcos, S., Dolcos, F. (2013). Neural signatures of the response to emotional distraction: A review of evidence from brain imaging investigations. Front. Human. Neurosci., 7, Article 200.

Jacob, R. and Parkinson, J. (2015). The potential for school-based interventions that target executive function to improve academic achievement: A review. Review of Educational Research, 85(4), 1–41.

Jones, S.M., Bub, K.L., Raver, C.C. (2013). Unpacking the black box of the CSRP intervention: The mediating roles of teacher-child relationship quality and self-regulation. Early Educ. Dev., 24(7), 1043–1064.

Jones, D.E., Greenberg, M.T., Crowley, M. (2015). Early social-emotional functioning and public health: The relationship between kindergarten social competence and future wellness. American Journal of Public Health, 105(11), 2283–2290.

Marryat, L., Thompson, L., Minnis, H., Wilson, P. (2014). Associations between social isolation, pro-social behaviour and emotional development in preschool aged children: A population based survey of kindergarten staff. BMC Psychology, 2(44), 1–11.

McLoyd, V. (1998). Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist, 53, 185–204.

Moffitt, T.E., Arseneault, L., Belsky, D., Dickson, N., Hancox, R.J., Harrington, H.L., Thomson, W.M., Caspi, A. (2011). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(7), 2693–2968.

O’Conner, R., De Feyter, J., Carr, A., Luo, J.L., Romm, H. (2017). A Review of the Literature on Social and Emotional Learning for Students Ages 3–8: Characteristics of Effective Social and Emotional Learning Programs [What’s known]. Institute of Education Sciences, Washington DC.

OECD (2015). Skills for Social Progress: The Power of Social and Emotional Skills. OECD Publishing, Paris.

Rimm-Kaufman, S.E., Pianta, R.C., Cox, M.J. (2000). Teachers’ judgments of problems in the transition to kindergarten. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15(2), 147–166.

Schonfeld, D.J., Adams, R.E., Fredstrom, B.K., Weissberg, R.P., Gilman, R., Voyce, C., Tomlin, R., Speese-Linehan, D. (2015). Cluster-randomized trial demonstrating impact on academic achievement of elementary social-emotional learning. School Psychology Quarterly, 30(3), 406–420.

Schultz, B.L., Richardson, R.C., Barber, C.R., Wilcox, D. (2011). A preschool pilot study of connecting with others: Lessons for teaching social and emotional competence. Early Childhood Educ. J., 39, 143–148.

Shoda, Y., Mischel, W., Peake, P.K. (1990). Predicting adolescent cognitive and self-regulatory competencies from preschool delay of gratification: Identifying diagnostic conditions. Developmental Psychology, 26(6), 978–986.

Silver, R.B., Measelle, J.R., Armstrong, J.M., Essex, M.J. (2005). Trajectories of classroom externalizing behavior: Contributions of child characteristics, family characteristics, and the teacher–child relationship during the school transition. Journal of School Psychology, 43, 39–60.

Thomson, K.C., Richardson, C.G., Gaderman, A.M., Emerson, S.D., Shoveller, J., Guin, M. (2019). Association of childhood social-emotional functioning profiles at school entry with early-onset mental health conditions. JAMA Netw. Open, 2(1), 1–33.

Vuilleumier, P. (2005). How brains beware: Neural mechanisms of emotional attention. Trends Cogn. Sci., 9(12), 585–594.

Watts, T.W., Gandhi, J., Ibrahim, D.A., Masucci, M.D., Raver, C.C. (2018). The Chicago School Readiness Project: Examining the long-term impacts of an early childhood intervention. PLoS One, 13(7), 1–25.

WHO (1997). Life skills education for children and adolescents in schools. Introduction and guidelines to facilitate the development and implementation of life skills programmes. Document, World Health Organization (WHO) Division of Mental Health.

WHO (2003). Skills for health: Skills-based health education including life skills: An important component of a child-friendly/health-promoting school. Document no. 9, WHO Information Series on School Health, World Health Organization.

- 1 Excerpts from the Kindness Curriculum (see section 1.3.3).