Chapter 5

Recovery: 1988–1989

Ken Lay had made big bets in precarious markets. At HNG, he had richly bid to win Transwestern Pipeline and then Florida Gas Transmission, overpaying somewhere between $100 million and $200 million (10–20 percent of the purchase price). Lay then had InterNorth overpay for HNG by at least $5 per share, or about $150 million. Although pushing that imprudence was arguably his fiduciary duty as the seller in the transaction, it was also driven by his desire to remove a pending shareholder suit. In a further act of pain avoidance, he then bought out Irwin Jacobs and Leucadia at a shareholder cost of $200 million.

Roughly $500 million—or about one-eighth of Enron’s total debt of $4 billion entering into 1988—was attributable to Lay’s aggressiveness, even hubris. And then came Valhalla’s $142 million oil-trading loss ($85 million, after-tax), which could have been far worse. If not for some deft cleanup, Ken Lay’s career might have taken a new turn in 1987 and changed business history.

As 1988 dawned, capital spending was down to a maintenance level of $185 million, about two-thirds of 1985’s actual. ENE’s dividend was frozen, as were the salaries for Enron’s top 60 corporate officers. A hiring freeze was in effect for major parts of the corporation. But greater efficiency was the good news amid the bad. From the time of the merger, pipeline cost per unit of gas delivered was down one-fourth, which included a reduction in field personnel of 23 percent.

Half sales of Florida Gas Transmission (in 1986) and Enron Cogeneration (in 1987) redeemed Lay’s weak balance sheet but left Enron’s earnings engine smaller. A minority sale of Enron Oil & Gas Company, scheduled for late 1987, was postponed owing to negative market conditions. Wall Street was uncomfortable with Enron’s 70 percent debt-to-capital ratio, as evidenced in rating downgrades by Moody’s and Duff & Phelps in 1987. Prior to Valhalla, Lay had promised 60 percent by year’s end.

Still, the dividend had been maintained, and expectations were high. The pipelines were beating the parent’s reserve for their transition (take-or-pay) costs, and growth was ahead from innovative rate-case designs and expansions. Gas marketing was a whole new profit center, with Enron the national leader. Regulation-enabled cogeneration remained lucrative even with Enron’s domestic pullback. And new expert leadership at Enron Oil & Gas created a significant upside.

Restructuring complete, Enron had a synergistic natural gas core, along with the perennial hope “to believe that the worst is over for the energy industry.” Consumer choice and national energy policy were trending toward gas and away from oil and coal for economic and environmental reasons, Lay and Seidl also noted in their 1987 annual report.

Ken Lay exuded optimism. His down-home, caring style made him likeable and believable to the Enron nation. “You can imagine,” Lay lieutenant James E. “Jim” Rogers, told Forbes, “how excited young people four or five levels down in the organization get when the chairman of the board calls to tell them, ‘You’re doing great.’” Upbeat, witty, confident, visionary—Enron had a leader. Who was to question a PhD economist with a storybook past and a seemingly unblemished business track record? (Valhalla just snuck up on him, remember.) This was the industry’s mover and shaker, according to the local, industry, and national media.

Enron was a well-regarded, first-class place to work. Despite the pressures, opportunities abounded for many in Enron’s workforce of 7,000. The buzz was that the smartest guys worked for Ken Lay and that there was always room for brainy people and top performers.

Enron had strong interlocking assets and superior divisional management. What was needed was normalcy, no surprises, to let the units work down the parent’s debt load. It was time to dust off and get to work on the mission Ken Lay had set the previous year: to become the premier integrated natural gas company in North America.

![]()

The year began with Enron’s letter of intent selling 50 percent of Enron Cogeneration Company (ECC) to Dominion Resources for $90 million. This was the price that had to be paid for Valhalla. But the good news was that by the time John Wing completed the sale five months later, the price had reached $104 million, thanks to some promising new projects in negotiation. All proceeds went to reduce debt, and a $40 million profit was taken for 1988 earnings.1

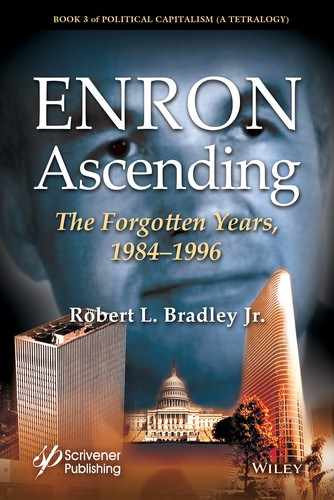

Figure 5.1 Financing with high-yield bonds (junk bonds) proved crucial for Ken Lay from the time of the HNG/InterNorth merger in 1985 through project financings in 1989, when Michael Milken was indicted for securities violations. Drexel Burnham Lambert filed for bankruptcy protection in 1990.

Wing would not run the renamed Enron/Dominion Cogeneration Corporation, however. Despite his new contract to run the independent power business for Enron, Dominion wanted one of its own in charge of the partnership. Lay really needed that deal, and so once again Wing was the odd man out, despite a redone contract that had four years to run. Wing negotiated yet another lucrative contract (each of the four better, with two coming and two going).

Some of this was about John Wing, a hot personality in a febrile business. Some of it was about working for a debt-laden, mistake-prone company and a chairman who had to please a whole lot of people.

Managerial Depth and Change

Through his personal dynamism and industry-leading compensation packages, Ken Lay had assembled a top management team heading into 1988. Each of Enron’s three major divisions (absent cogeneration) had strong, innovative leadership, starting with the Gas Pipeline Group (GPG) in its three dimensions: intrastate, interstate, and national marketing.2

Intrastate, Gerald Bennett was doing as well as could be expected in the overbuilt, low-margin Texas market. Houston Pipe Line was Enron’s weak sister, although the synergies provided by Bammel storage redounded to the benefit of the rest of GPG. In this respect, Ken Lay’s restructuring moves looked smart compared to Bill Matthews’s cocoon strategy for the old Houston Natural Gas.

Interstate, all three pipelines were evolving from gas merchants to transporters, while getting their take-or-pay costs under control. Jim Rogers and team were playing the FERC liberalization game expertly, offering new products with customer support and reaching rate-case settlements with upside profit potential. Transwestern was setting an industry standard by entrepreneurially working within regulatory constraints. Florida Gas was making natural gas the fuel of choice at Florida electrics for the first time since 1970. And Northern Natural Gas Pipeline was its usual solid self, just needing some winter cold snaps to keep its volumes high.

On GPG’s nonregulated side, Enron Gas Marketing was emerging as a bona fide profit center, pointing the industry into a new era of gas commoditization.3 Ron Burns was EGM’s leader, aided by Transco-exes Claude Mullendore (supply) and John Esslinger (sales). Armed with a blanket certificate from FERC, EGM was buying and selling gas nationally under short-term and long-term contracts. Enron was building up unique capabilities with a first-mover advantage.

Enron Liquid Fuels (ELF), under Valhalla hero Mike Muckleroy, had been reshaped amid tough industry conditions and was back to profitability. ELF’s asset base of $750 million was housed in five divisions: liquids processing, liquids retailing, liquids pipeline, oil transportation and trading, and international.4 And Forrest Hoglund was hard at work reconfiguring the valuable assets of Enron Oil & Gas Company.

Ken Lay’s talent was not lost on Enron’s rivals—and the energy industry more generally. At a time when companies were restructuring and looking for change agents, Enron executives were at the top of many headhunter lists. By first-quarter 1989, four Enron notables had left to take top jobs elsewhere. “While we will miss their ideas and leadership talents,” Ken Lay remarked, “their departure gave us the opportunity not only to promote equally aggressive and innovative mangers but also to streamline further our management organization and thus further reduce overhead costs.” Losing experience seemed not terribly important at the time, but some of Enron’s emergency brake for Lay’s hyper-speed would no longer be in place.

Enron’s competition was being upgraded. Clark Smith left Transwestern Pipeline to become CEO of Coastal Gas Marketing Company, a start-up within Oscar Wyatt’s Coastal Corporation, which would go head-to-head against EGM. Jim Rogers jumped industries, becoming CEO of Public Service Company of Indiana (PSI Holdings Inc.; later Cinergy Corp.; then Duke Energy). His blend of political capitalism and market entrepreneurship made him in demand at the troubled Midwest electric utility, one that needed a fresh start with state and federal regulators, as well as a new strategic direction.

Dan Dienstbier, Rogers’s boss as head of GPG, left to lead a smaller gas company, escaping a corporate culture in which he was never really comfortable.5 With Dienstbier’s departure, the old InterNorth imprint was with a new generation: Ron Burns and, behind him, Ken Rice and Julie Gomez, both of whom would excel within EGM and its progeny.

Another Omaha talent who would eventually assume responsibility for all of EGM’s back-office operations (accounting, contracts, etc.) was Cindy Olson. She would later head community affairs for Enron, among other responsibilities, becoming a top lieutenant to Ken Lay as his outside ambitions got bigger and bigger.6

![]()

A change at the top of Enron occurred in early 1989. Mick Seidl had been Ken Lay’s fix-it man almost from inception, with mixed results. Valhalla, in particular, blew up on his watch. Richard Kinder, even before becoming chief of staff in August 1987, had been asserting himself as Lay’s fix-it man—with good results.

Over time, Seidl became redundant between nice-cop Lay and tough-cop Kinder, although there was always plenty for Mick to do. So it worked out well when Maxxam’s Charles Hurwitz offered Seidl the presidency of Kaisertech Ltd. (Kaiser Aluminum and Chemical Company). Upon Seidl’s departure, Lay retook the president’s title but left the COO position open. Rich Kinder had been promoted to vice-chairman and elected to Enron’s board of directors in December 1988, as well as becoming head of the Gas Pipeline Group, replacing the recently departed Jim Rogers.

As EVP and chief of staff, Kinder had been involved in practically every urgent matter. Just about every department reported to the hands-on Kinder: accounting, administration, corporate development, finance, human resources, information systems, law. With a photographic memory and an intuition for numbers, he knew what needed to be known about the myriad businesses beneath him. Ken Lay was also gifted but more interested in issues and events outside the window.

Kinder lived between Enron’s walls, and though he was tough, he was approachable. “He was with you and on you, every week,” remembered one pipeline head. For those who worked hard, stayed focused, and spoke straight, Rich Kinder was cordial; for everyone, this taskmaster was a good custodian of assets.

Kinder made his mark at a momentous meeting to resolve the conflict between the pipelines and marketers over the future of the gas merchant function. In Enron lore, it would become known as the Come to Jesus meeting.

The pipelines wanted to remain in their familiar role as buyers and sellers of gas. After all, they had gathering systems, contracts with producers, and time-honed procedures that ensured reliable supply. Only acts of God, such as well freeze-offs and hurricanes, could keep them from their appointed rounds. But marketing affiliates could make a margin on the purchase and sale of gas in interstate commerce under the new rules from Washington. The gas historically controlled by the interstates needed to be relinquished for Enron Gas Marketing to buy, sell, and arrange transportation.

The pipelines were uncomfortable with this shake-up. With the culture conflict between Houston and Omaha largely overcome, the future of the gas-merchant function was the major issue at Enron.7

Lay supported EGM as the future of the gas business. It was simple: Two profit centers were better than one, even with the transition costs (take-or-pay liability) of pipelines exiting the merchant function. A new generation of information technology, Lay and others believed, would ensure reliability in the new world where marketers, not the pipelines, coordinated gas supply.

Lay opened the meeting of Enron’s top corporate officers and division heads with polite reasoning to this effect. The merchant function should transition to EGM for the overall good of Enron. Kinder took over from there. His voice rising, he presented example after example of the warring factions’ politicking, back stabbing, and power plays. “There are alligators in the swamp,” Kinder yelled. “We’re going to get in that f—— swamp, and we’re going to kick out all the f—— alligators, one by one, and we’re going to kill them, one by one.”

The room got the point. Lay liked how Rich got things done. This was a defining moment for Enron and Kinder personally. It cleared the crossing, allowing EGM to speed ahead and become the largest and most profitable gas marketer in the United States.

The weekly corporate staff meetings changed too when Kinder took over from Seidl. No longer was the go-around a beauty pageant for each divisional head to describe good things happening in the unit. It was now bad-news-first and getting hard decisions made. It was about bottom lines and accountability.

Ron Burns remembered a “huge cultural change” at the Monday confabs, which began with lunch and could last into the evening. “Kinder took charge to really make sure that all the issues were on the table, that all the alligators were on the table, and we slayed as many as we possibly could.” And Kinder never forgot what was said or promised to him.

Monday afternoons were tough. But for the performers, airing the issues and getting consensus behind tough courses of action were prized. “As long as you had your act together and made your pitch, you could get a decision that day,” Burns remembers. “That is when we went from playing defense to playing offense.”

Rich Kinder was the clear number-two executive at Enron by late 1988. After a strong close to 1989 (discussed later in this chapter), Lay and the board would name him Enron’s new president and COO, with Lay remaining chairman and CEO. The Lay-Kinder era would continue through 1996.

Repositioning EOG

Forrest Hoglund and Ken Lay were courting potential investors in Europe about taking Enron Oil & Gas Company public. The two were on the plane when Lay got the phone call from Mick Seidl about Valhalla. Had the trading fiasco erupted a month earlier, Hoglund might not have been in Enron uniform. He already had a good job, and just about everyone wanted Forrest Hoglund for their exploration and production company.

Lay’s winning courtship was the talk of the industry. “Hiring Hoglund shows Enron is serious about putting more emphasis on this end of the company,” remarked one securities analyst in the Wall Street Journal. “It gives them instant credibility.” True to form, EOG’s new leader would create a thriving, valuable enterprise—and prove to be one of Ken Lay’s best moves.

Hoglund relished the idea of building up the company and making himself and his colleagues wealthy in the process. But EOG could not be like Enron. The company-within-a-company had to have its own rules and culture to be able to go public. And then there were expenses. When Ken Lay offered the use of an Enron plane to commute between Dallas and Houston (the Hoglunds maintained dual residences), Forrest demurred. “It costs $2,000 to take the plane off, and I can ride Southwest Airlines for $100,” he responded. “Why would we do that?”

Looking back, Hoglund contrasted his “much different outlook on costs” to Lay’s. Industry conditions precluded such luxuries, and the CEO set the example. As a minority shareholder of the company that was going public, Hoglund was thinking of himself too.

EOG needed reshaping to become, in Hoglund’s words, a “low-cost, basic, get-it-done kind of company.” Its properties needed to be grouped into core for development and noncore for disposal. Intellectual capital needed to be reshaped from an incumbency that seemed to have “cornered mediocrity.” In his introductory meetings, Hoglund told his managers that half of them would not get it and leave, and the other half would become millionaires. “I undershot on both cases,” he would later say. About 80 percent of the managers would be changed out, and most of the new team would become wealthy.

EOG needed to restructure its South Texas joint-venture (“farm-out”) contracts that were too skewed toward the partner, devise a plan to develop and market its large gas reserves at Big Piney in Wyoming, and enter into marketing arrangements to extract more margin. But rather than consolidate EOG in Houston, as had been done in the past year, decision making needed to be near the action. Separate offices and profit centers were set up in Corpus Christi, Denver, Midland, Oklahoma City, and Tyler—creating companies within Hoglund’s company.

Drilling required cash, but EOG’s cash flow was needed by Enron. That was why Lay and Hoglund were touring Europe in search of investors when Valhalla 2 hit. An initial public offering (IPO) was set for pricing on October 19, 1987. But that turned out to be “Black Tuesday,” the day that the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) fell 22 percent, almost double the percentage fall of the Great Depression’s “Black Monday” in October 1929. EOG would have to be a wholly owned subsidiary of Enron a while longer, which gave Hoglund an opportunity to strengthen and streamline the company and create a better story for analysts and would-be buyers.

In April 1988, with the stock market fully recovered, Enron decided to put Enron Oil & Gas up for sale. Enron and its bankers floated a value for EOG at as much as $2 billion, and both expressed some hope that EOG’s proved reserves of 1.4 trillion cubic feet of gas and 42.3 million barrels of oil would fetch a $1.50/MMBtu equivalent, valuing the company at $2.5 billion.

But oil and gas prices were in the doldrums, and Tenneco and other large companies were also selling large reserves. Analysts were valuing EOG between $1.25 and $1.75 billion, every dollar of which was needed by Enron to pay down its $3.6 billion debt in order to lower interest costs and raise net income.

Nearly a dozen formal bids came by the July deadline. Internally, Enron was looking for $1.8 billion, but the high bid was $1.3 billion, about 15 percent below EOG’s book value—and a straight discounted valuation for EOG’s proved reserves. There was no premium for undeveloped properties or management.

Hoglund, Lay, and Enron’s board were of one mind: It would be disadvantageous for Enron stockholders to sell. All the bids were rejected; EOG would again stay wholly within Enron for the time being.

Still, Lay expressed his hope that wintertime would bring increased demand for long-term, higher-priced gas contracts, thus increasing the value of reserves in the ground. “Reducing our debt is still a real high priority for us,” Diane Bazelides of Enron’s media relations added, “and we’ll continue looking to all avenues until we’ve reduced that debt.” Wall Street, however, reacted sternly to the news, sending ENE down 7 percent to 38⅞.

With debt of $3.9 billion at the end of third-quarter 1988 and a loss that quarter of $14 million from continuing operations, Enron still needed to monetize its value in EOG. Plan B was for EOG to sell between $200 million and $300 million in nonstrategic properties. In fact, $253 million would be sold in the fourth quarter, representing most of EOG sales that year of $282 million. Better yet, reserves were reduced by only 13 percent. EOG was left with the assets it wanted to take public.

Meanwhile, things were getting cleaned up at the core. Hoglund’s first full year produced income before interest and taxes (IBIT) of $13 million, a rebound from a loss of $41 million in 1987. In retrospect, this was EOG’s turnaround year.

Enron’s 1988 Annual Report described a good year for EOG’s “decentralized, profit-conscious management team.” EOG’s 84 percent drilling-success rate was a company best. A major gas find near Matagorda Island in the Gulf of Mexico added to proved reserves. Overall reserve additions costing $0.60 per Mcf joined sales made at $1.56 per Mcf. EOG’s aforementioned property sales reduced Enron’s debt, contributing to a credit-rating upgrade for the parent. EOG was unlocking value that was only partially reflected in ENE.

But something else kicked in that would be a real moneymaker. Thanks to regulatory opportunity exploited by John Wing, a 48 MMcf/d contract between EOG and Enron/Dominion’s cogeneration plant in Texas City was executed “at prices substantially above spot market levels.” In fact, it was almost double the going price for gas, a premium that alone increased EOG’s revenue by $44 million in 1988, the first full year of the contract.

More than purely free-market forces were at work with this sweetheart deal. Specifically, the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act of 1978 (PURPA) set forth a methodology that tied the power-sales agreement to the purchasing utility’s avoided cost, or the cost of power that it would otherwise generate or buy.

For Texas Utilities Electric Company, the ultimate buyer (via a wheeling arrangement with Houston Lighting & Power, which did not need the power), the avoided cost was based on constructing a new coal plant. Coal plants, which now had to be outfitted with scrubbers and other pollution-control equipment, were more capital intensive than gas plants, particularly a state-of-the-art high-efficiency cogen plant.

So, in this case, the avoided cost was determined in state regulatory hearings to be $1,100 per kilowatt of installed capacity—versus Enron/Dominion’s $300 per kilowatt cost. The power-sales contract was so high that natural gas could be profitably purchased (from EOG, providing a windfall) at $3.25/MMBtu (with a 6 percent escalation factor) at a time when spot gas was averaging under $2.00/MMBtu.

This was a home run compared to what regulators could have required: basing the power contract on an avoided cost tied to the cost of constructing an efficient cogen plant. The gas-purchase price would then have had to be done closer to spot. But Texas Utilities did not care, because its profit under public-utility regulation was based on rate base, with gas costs a ratepayer passthrough. Unlike a free-market company, this franchised monopolist had no incentive to maximize the spread between costs and revenue.

Federal power law was very kind to Enron at a time of great need for Ken Lay.8 State regulators were very generous too, blessing high avoided costs and thus, indirectly, premium pricing for long-term contracts. It was good eating at the trough of public-utility-regulated companies, at least during the 1984–89 heyday of PURPA.

![]()

In October 1989, Enron floated an IPO for 16 percent of EOG, priced at $18.75 per share. The offering’s 11.5 million units were placed, trading on the Big Board under the symbol EOG. Enron netted $202 million, and its remaining interest, coupled with debt owed by EOG to the parent, gave Enron an asset on its balance sheet worth $1.6 billion.

Forrest Hoglund, with help from the extraordinary Texas City contract, had created a lot of enterprise value to help Ken Lay and Enron turn the corner. And it would get better. The offering price appreciated by one-third by year end, giving Enron a $2 billion asset. This equated to about $40 per share of ENE, leaving $17 for the rest of Enron: the pipelines, the gas-liquid assets, the cogen interests, and the emerging marketing division. But far from irrational, the drag was the debt burden associated with these valuable assets. Still, optimism abounded. “It is obvious,” stated Ken Lay and Rich Kinder, “that potential remains for continued growth in shareholder value.”

Figure 5.2 Enron Oil & Gas, advertised as “America’s Pure Natural Gas Play,” launched an October 1989 public offering that valued the company at $1.6 billion. Forrest Hoglund, chairman and chief executive officer, was off to a very fast start in a low-price environment.

EOG’s public offering was accomplished despite uncooperative natural gas prices—at least in the spot market. Long-term deals that could be priced at a premium to spot were sought, and Ken Lay would become a spokesman against “irrationally low” gas prices in the years ahead.9

Recommitting to Cogeneration

Cogeneration was an exciting new business driven by technological advance, low natural gas prices, and a federal law requiring electric utilities to favorably contract with qualifying independent developers. Ken Lay had pushed cogeneration back at Transco; as CEO of Houston Natural Gas, he got into the game by hiring John Wing and Robert Kelly away from Jack Welch at GE.

Enron was well situated near the industrial belt of the Texas Gulf Coast, a top market for cogenerated steam and power. As a gas-transmission company, Enron was pursuing another prime market for cogen: steamflood-enhanced oil recovery in central California. This was the planned destination of the upstart Mojave Pipeline Company, a joint project of Enron and El Paso Natural Gas Company.10

Enron had done well with its investment in the Bayou Cogeneration Plant. Ken Lay wanted a stable of such projects, but Lay crossed Wing in the wake of the InterNorth merger by giving the combined companies’ cogen responsibilities to Howard Hawks’s Northern Natural Resources Company (NNR).

After a brief heyday, during which the Texas City project (“Northern Cogeneration One”) was agreed to and entered construction, things changed radically at NNR. The Omaha division found itself going from growth to retrenchment, then Hawks departed. Lay got Wing back to refinance Texas City off–balance sheet, with Enron taking full ownership (up from 50 percent), to complete the 377 MW Clear Lake Project, and to wind up a cogen project in New Jersey.

John Wing may have been a bucking bronco, but he was immensely talented and someone Enron needed in-house, or at least under a contractual collar. Not just anyone could execute a fast-track moneymaking cogen project, particularly when a multitude of contracts had to be buttoned down to allow the project to be self-financed (the type of project that Enron had to have, given its weak balance sheet).

Building and operating steam and power plants utilizing the very latest in technology required technical expertise and precise, urgent management. Cogeneration could be the highest return-on-equity (ROE) opportunity for an energy company, offering estimated pretax returns of 18–20 percent, but only if the projects were done right. And the competition was getting intense, as utilities and regulators tightened up the rules.

It was far better to have John Wing on your side. InterNorth found that out the hard way in the 1985 merger negotiations with HNG. Enron found it out a year later by leaving big money on the table regarding its 42 percent investment in a $120 million, 165 MW plant in Bayonne, New Jersey. Wing, negotiating for the developer and receiving a 1 percent override for his trouble, cut the deal of all deals. It wasn’t that the investment for Enron was not good—it was very good. But it could and should have been better.

Newly formed Enron Cogeneration Company (ECC) signed the deal with Cogen Technologies Inc. (CTI), an upstart private company majority owned by Robert McNair. The agreement began with 85 percent of profits going to Enron, the major equity investor. But then profit sharing flipped: a 50/50 split if and when the project’s ROE reached 23 percent and then another readjustment, to a 15/85 split (in favor of CTI), should the project reach a 30 percent return.

Figure 5.3 Bayonne Cogeneration Plant in New Jersey was the inaugural project of Robert McNair’s Cogen Technologies. A decade later, Bayonne and two neighboring CTI plants would be sold to Enron for $1.1 billion and debt assumption, enabling McNair to found an NFL franchise, the Houston Texans.

Entering service in September 1988, Bayonne quickly reached and exceeded these thresholds, making tens of millions of dollars for McNair and CTI. But how did something so extraordinary happen?

Working closely with GE—the prime contractor and the turbine supplier—McNair and Wing brought the plant into service ahead of schedule and below budget. But this was just the start of something extraordinary. A federal investment tax credit was enacted just as the project was being completed, adding 10 percent to the rate of return. Accelerated depreciation in the same law further sheltered profits from income taxes. Thank you, political capitalism.

A fourth factor concerning risk versus reward came out all roses for McNair and his other private investors (including Wing). Anticipating rising gas prices, the major electricity purchaser, Jersey Central Power & Light, required CTI to enter into a power-sales contract based on a spread reflecting fixed gas prices as of 1985.

Without forward markets for natural gas to lock in prices, McNair could not effectively hedge his exposure under his sales contract. Jersey Central, meanwhile, was impervious to (falling) price risk because its power-purchase contract was approved by its state regulators. A floating power price, alternatively, which McNair’s CTI preferred, would have locked in a spread with a market-price purchase contract. As it was, a big bet on the future price of gas was made at the power buyer’s insistence.

Jersey Central guessed wrong—badly. Instead of escalating, gas prices plunged in 1986 and stayed low. Bayonne’s profit margins increased by one-third after the project came on stream, with spot gas purchased at well below 1985 levels.11 Continuing low prices well into the 1990s would add to the win for McNair—and the loss for customers of a monopolist utility that, as the customers’ agent, bet wrong.

All said, Bayonne achieved its 23 percent rate of return in two years and 30 percent return in three, leaving CTI with 85 percent of the profit for the life of the plant. So, with McNair putting up the sweat equity and several million dollars in development costs versus Enron’s $14 million, McNair found himself making more money from the project each month than Ken Lay made in a year as Enron’s CEO.

“You’re making so much money!” Ken complained to Bob. But Enron had received a handsome return from the project, and a deal was a deal, even if Wing and McNair bested Lay and Seidl—and the man caught in the middle, Robert Kelly, who was now heading Enron Cogeneration Company.

Cogen Technologies would go on to become one of the very top independent power developers in the nation. The sale of CTI’s major asset to Enron in 1999 (McNair took cash, not stock) would make McNair one of Houston’s wealthiest men and provided the means to buy an NFL football team for his hometown, a deal that was also made possible by a new taxpayer-supported stadium, in no small part the result of an intense lobbying effort by Ken Lay and Enron several years before.12

![]()

Robert Kelly had followed Wing out the door in early 1988 when the top job of Enron/Dominion Cogeneration Company went to David Heavenridge from Dominion. (The half sale was necessitated by Valhalla’s oil-trading loss.) Kelly and Wing formed Wing Group in The Woodlands north of Houston and advised Enron and other clients.

Heavenridge’s Houston-run operation was not getting deals done. There were no ground breakings, just managing Enron’s 1,000 MW interest in four plants.13 Other companies were more active and announcing projects—CTI, Mission Energy (Southern California Edison Company), even Enron-ex Howard Hawks’s Tenaska, based in Omaha.

With Heavenridge’s heavy-handed management causing dissent, Ken Lay summoned Wing, necessitating a fifth long-term (five-year) contract (all occurring within four years of each other). Wing would agree to the contract but would remain a consultant, not an employee.

In early 1989, Enron Power Corporation (EPC) was formed as a second cogeneration division, separate from Enron’s half-stake in Enron Dominion Cogeneration Company, now a passive investment. Wholly owned EPC was about the future; EDCC was the past. With John Wing as chairman and Robert Kelly as president, EPC was run out of The Woodlands. (Wing’s new contract required that his office be within 25 miles of his primary—Woodlands—residence, and the Enron Building was 30 miles away.) The Wing Group, meanwhile, continued in non-Enron spheres.

But cogeneration activity had slowed down considerably in the United States. The domestic projects that were on the drawing board of ECC/EDCC were stuck in negotiations. The new opportunity was international. England, in particular, was ripe for a new technology that could underprice the coal-fired power that the country had grown up on.

![]()

Margaret Thatcher was privatizing and otherwise liberalizing the electricity sector in the United Kingdom, and new gas finds were coming from the North Sea. The prospects looked very interesting for an interloper such as Enron to shake things up. But compared to the status quo, this required back-to-back contracts allowing everyone—gas sellers, steam and power buyers, and project developers—to win.

Enron Power Corporation was reorganized to do just that. Wing was chairman, and under him as president and CEO was Rebecca Mark, now with a Harvard MBA. Robert Kelly was named chairman, Enron Power UK.

In late 1988, what would become the world’s largest gas-fired, combined-cycle electric-generation plant was born when Wing and Kelly met at London’s Heathrow Airport with two executives of Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI), a major consumer of steam and power. EPC’s spreadsheets showed a substantial cost savings for ICI from a new state-of-the-art combined-cycle plant under a variety of price scenarios with gas from the North Sea. But Enron could not buy that gas. ICI had the legal means to break into British Gas’s stranglehold—and the incentive to do so, given the prospect of buying cheaper steam and power.

The proposed project was big—larger than any such project built in the United States. Financing a new North Sea platform was very expensive, and the cost of gas had to be driven down to offer the savings that the purchase contracts required. Customers other than ICI were needed to make the project viable. Within the United Kingdom’s restructured power market, the old regime of several generators selling to a dozen distributors was giving way to new independent contracting.

The new project that Wing and Kelly had in mind played right into the public policy changes that allowed self-interested buyers and sellers to intersect. A five-utility consortium signed on to more than double the purchases that ICI alone committed to.

Gas supply was now the trigger point. Kelly initiated simultaneous discussions with Amoco (Everest-Lomond Field), Statoil (Sleipner Field), Marathon-BP (Bray Field), and Phillips (J-Block Field). With discussions advancing, Enron signed a letter of intent in February 1989 to build a 1,750 MW gas-fired cogeneration plant near the town of Teesside in England. The project, the world’s largest, priced north of $1 billion, compared to the net worth of Enron itself ($1.6 billion). Ken Lay’s temerity again prompted him to throw the dice, betting on the smarts and fortitude of the mercurial John Wing.

![]()

At decade’s end, PURPA-driven independent power market was responsible for 30 percent of new US electrical generation capacity versus 5 percent in 1984. Enron was right there. The 1989 Annual Report described EPC as “one of the nation’s largest independent producers of electric power via natural gas-fired combined cycle and cogeneration technology.”

Now, “Enron’s total package concept offering a wide range of coordinated services” was going abroad. The future, Lay proselytized, belonged to natural gas—a cheaper, cleaner alternative to coal and fuel oil and certainly a cheaper alternative to nuclear power.

Pipeline Entrepreneurship

Enron was spreading its wings, but natural gas transmission still represented two-thirds of the company’s assets and income. Generating several hundred million dollars a year in cash flow was no small feat. Interstate pipelines as a whole saw their return on equity fall in half during the 1980s—from around 15 percent to 7 percent. Not Enron, whose collection, including its interest in Northern Border, remained consistently in the double digits.

Jim Rogers declared in 1986 that interstate transmission “is no longer a rate base business.” How true. To make its FERC-authorized rate of return, an interstate needed to do more than just keep its compressors running and shiny. This was not the 1950s and 1960s, when such investment was akin to holding a bond, or the gas-short 1970s, when financial undercollection in one period could be recouped in the next.

Now, pipeline earnings were at risk. The minimum-bill contracts guaranteeing income whether or not the customers took the gas were gone. Rate-design changes allowed the customer to avoid some fixed charges if the gas was not physically taken. Pipeline payments to reform its take-or-pay contracts with producer contracts were not automatically passed through to customers in rates, legally or even economically. The pipeline itself would have to absorb some of its take-or-pay costs—a compelling reason to minimize those expenses.

All said, the pipeline had to earn every dollar it could, whether by increasing revenue or decreasing expenses. Customers had to be courted with a menu of sale and transportation options to maximize a pipeline’s throughput. Pipelines needed to be competitive to deliver gas below the cost of fuel oil to dual-fuel-capable customers—and in some cases to keep a customer in business.

![]()

Enron was well positioned. Its four-pipeline hub-and-spoke system offered logistical opportunities that smaller or less congruent systems could not. Gas could be purchased from more regions, and Bammel storage ensured flexibility at the center. Geographical overlaps between Enron’s pipelines (HPL and FGT to the east; HPL and Transwestern to the west; Transwestern and Northern Natural to the north) allowed consolidation of field operations.

At headquarters, the traditional gas-transmission functions—accounting, administration, finance, marketing, rates, regulatory affairs, and supply—did not need to be done by each pipeline. Some functions (buying gas, dispatching) went corporate-wide beginning in 1987. Even before then, Transwestern and Florida Gas shared managerial talent. (“We found out that we could manage two pipelines at about the same cost that you could manage one,” Stan Horton remembered.) Northern Natural, however, located in Omaha to be near its customers, operated more autonomously.

In March 1988, Enron’s interstate pipelines under Jim Rogers dispensed with its presidents and centralized administration, finance, marketing and supply, and rates and regulatory affairs. Horton, previously president of Florida Gas, was named vice president of marketing and production for Enron Interstate Pipelines. William “Bill” Cordes, previously vice president of regulatory affairs for Northern Natural, was now director of rates for Florida Gas, Northern Natural, and Transwestern.

This centralization involved 90 layoffs and relocating 140 employees from Omaha’s Northern Natural to Houston. Each pipeline, though without a president, had an executive vice president: Don Parsons, Florida Gas; Clark Smith, Transwestern; and at Northern Natural, the former FERC boy wonder Rick Richard, who had pushed through open-access restructuring, jumped to industry, and soon landed a job at Enron.

Still, this integration had its limits. FERC regulation was based on a separate rate base and cost allocation for every interstate. Each pipeline had its own customer base. Within a year, the president titles were back with the pipelines. Nevertheless, functional integration occurred with costs savings.

![]()

Enron did not wait around for gas prices to rise before renegotiating its uneconomic producer contracts. Ken Lay rejected that strategy as more heart than head. The interstates were instructed to settle their take deficiencies quickly in the belief that protracted negotiation and litigation would backfire and that money could be saved by offering cash-strapped producers instant liquidity. Wall Street did not like uncertainty and did like resolution.

The strategy exceeded expectations. Enron’s take-or-pay liabilities, which peaked near $1.2 billion in mid-1987, ended 1988 at $570 million and fell to $160 million a year later.14 Compared to its 14 percent share of the national gas market, Enron’s total exposure was never over 5 percent of the interstate industry’s bill. Transco Energy, meanwhile, was stymied by take-or-pay. Payouts of $688 million through 1987 would surpass $1.1 billion by the time an embattled George Slocum resigned in 1991, and hundreds of millions in claims still lingered.15

Whereas Transco’s Ken Lay had sought a legislative fix to a big take-or-pay problem, Enron’s Ken Lay favored self-help to resolve a smaller problem. It was all about competitive position, not free-market philosophy.

![]()

The man in charge of Enron’s interstate pipelines was described by Natural Gas Week as “the visionary missionary of natural gas marketing and Wunderkind executive of Enron Corp.” Jim Rogers—who declared back in 1986 that “we’re all getting comfortable with chaos”—had to run fast in a chancy environment. It was tough to maintain earnings, let alone increase them, given a depreciating rate base upon which regulated returns were calculated—even assuming that a pipeline could make its authorized rate of return. Many did not.

Rogers knew the regulatory game from the other side, having previously worked at FERC as deputy general counsel for litigation and enforcement. His entrepreneurial side was devising strategies to probe, even stretch, the regulatory boundaries for efficiency and financial gain.

The Kentucky native also had a gift for oratory, giving more than 30 speeches between 1985 and 1988 on the political economy of the midstream gas sector. In one, Rogers asked why the mighty dinosaur went extinct and the lowly cockroach thrived. Enron-the-roach was practicing “resilience and ability to change direction”—and surviving in the natural gas industry. No wonder he was a Lay favorite, a protégé. And little wonder that when Rogers spoke, the gas industry and its regulators listened.

Back in mid-1986, with Transwestern fighting the California natural gas wars, Rogers proposed a new rate design to reward producers who stood ready to supply gas whether or not the customer took it. Californians and their regulators were having their cake and eating it too by buying cheaper interruptible 30-day supply yet expecting long-term, guaranteed gas to still be there. “Spot gas is very seductive,” Rogers analogized, producing “a narcotic effect on those who start taking it.”16 Supply security, he argued, required the customer to pay a demand charge, a fixed monthly fee separate from the variable costs of taken gas, for producers standing ready to provide firm gas. Such revenue for producers would alleviate take-or-pay payments that pipelines would otherwise have to make.

The next year, FERC Order No. 500 included a provision authorizing a gas-inventory charge (GIC), more or less what Rogers had in mind. Transwestern Pipeline would be the first to implement a GIC, an idea-to-action plan that characterized Rogers’s pipelines, although customers avoided it by electing not to buy pipeline gas in favor of (cheaper) spot supply.

Enron’s interstates were market and regulatory leaders, not unlike Transco Energy under Ken Lay. Transwestern in 1989 became the first transportation-only interstate in FERC’s open-access world. The multidecade service obligation was removed, with marketers selling gas and pipelines transporting it. The GIC and the flexible purchased-gas adjustment (PGA) clause, described in chapter 3, were Enron ideas. Northern Natural was the first interstate to get blanket authority to sell its gas off-system and, like Transwestern, had been one of the early pipelines to go open access back in 1986.

Other innovative proposals teed up at FERC were less successful. Rick Richard and Jim Rogers proposed that Northern Natural set rate maximums with seasonal (monthly) pricing within the (averaged) cost-of-service constraint, replacing one set maximum price. “Pipeliner Rick Richard is building a better mousetrap,” opined John Jennrich in Natural Gas Week. “What he hopes to catch is more certainty in gas supply planning and pricing.”

Mick Seidl, at the time Enron’s number two behind Lay, joined Jim Rogers’s push for less FERC and more market forces. Market and regulatory change was remaking the industry, but “cradle-to-grave” Natural Gas Act regulation was inhibiting and unfair to pipelines.

“We at Enron support the move toward deregulation and simplification of the natural gas industry,” Seidl remarked at the annual Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA) conference in Houston.17 “We are firmly convinced that over time the invisible hand of Adam Smith can more effectively and efficiently protect the interests of natural gas consumers than can the most thoughtful and well-meaning efforts of federal regulators.”

As it was, the industry was immersed in regulatory-related matters from routine filings to formal rate cases. “The btu value of the paperwork now exceeds the btu value of the gas,” one wag complained about FERC Order No. 500. Pipeline expansions were in slow motion, part of FERC’s backlog of pending certification requests totaling $14 billion in costs and 18 billion cubic feet per day of capacity, a multiple of that of Enron.

Still, Enron was not pushing for a true deregulated market. “Regulation is in the public interest because it tends to protect gas pipelines from risks to which they would be exposed in a competitive environment, and hence promotes stability and thereby reduces costs of capital and benefits consumers,” reported the Council on Economic Regulation, an ad hoc group that included Enron’s Richard, previously a FERC commissioner who had helped author Order No. 436. “If deregulated, economies of scale in transportation would result in competitive entries into the market, exercise of market power, and probable predatory pricing and eventual consolidation.”

This was the case for regulating a so-called natural monopoly, little changed from that espoused by Chicago Edison’s Samuel Insull to the electric industry a century before. But several years later, Ken Lay would reject this case for public-utility regulation in a speech before the Cato Institute in Washington, DC.18

For now, however, regulatory balance was sought. Peter Wilt, head of Enron Interstate’s regulatory and competitive analysis, complained at industry conferences about FERC’s “dual approach to supply availability”—regulation here and free-market forces there. Wilt and Enron favored deregulation so long as pipelines received fair value for its public-utility service. The policy chief of the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America (INGAA), the pipeline trade group, similarly urged “a market-responsive commission.” As it was, FERC was taking a guilty-until-proven-innocent approach to proposals from a market-responsive industry.

In a stubborn buyers’ market, pipelines were stuck with take-or-pay liabilities and public-service obligations just as their customers were unilaterally freed by administrative fiat to buy cheaper nontraditional supplies. The “uneven mix” of edict and markets needed more of the latter, Seidl complained. The escape from a regulatory balkanized past, including wellhead decontrol for the first time in several decades, deserved a bilateral, lightened approach.

In the fourth quarter of 1988, Rogers (just 41) was hired away from Enron by a struggling Midwest electric utility, Public Service Company of Indiana (PSI), whose coal-dominated generation assets needed modernization. PSI had suspended its dividend because of a failed nuclear project and was stuck in neutral. The folksy Rogers was just the leader to bring new thinking and urgency to state and federal regulators, customers, and investors. Tumult in the gas industry was good training to this end, PSI’s board determined.

Rogers would turn things around at his new job in the next years, although a financial home run was precluded, given the strict rate-base regulation governing his assets. In the process, Rogers would actualize the political capitalism model that Ken Lay was employing at Enron by embracing—ahead of his electric utility peers—the global-warming issue and mandatory open access for electricity.19

Ron Burns, 36, took Rogers’s place running the interstate pipeline group. There was only one Jim Rogers, but Burns had cut his teeth in rates and regulatory affairs and sported hands-on experience in transportation and marketing. Burns’s contagious can-do spirit made him a superior leader, helped by his all-American build and looks. With Seidl, Dienstbier, and now Rogers gone, Burns reported to Rich Kinder, who was both president of the gas pipeline group and vice-chairman of the parent.

Reporting to Burns from the nonregulated gas side was Gerald Bennett, by now an Enron veteran, who oversaw both Houston Pipe Line and Enron Gas Marketing. The pipeline presidents under Burns were Stan Horton (Florida Gas), Rick Richard (Northern Natural), and Terry Thorn (Transwestern).20

Horton, in particular, was a rising star who was on his way to becoming Enron’s top pipeline executive. He had been on the regulatory side of Florida Gas when Ken Lay and HNG called in late 1984, had helped Transwestern on the fly, and now had his own pipeline to run, something he could have scarcely imagined just four short years before.

Oliver “Rick” Richard was a talented, colorful character who had gone from being the youngest commissioner in the history of FERC (1982–85), where he led the regulatory restructuring of the interstate gas industry, to general counsel for Tenneco’s gas-marketing arm, Tenngasco. He joined Enron in early 1987 as vice president of regulatory and competitive analysis. A Rogers hire, Richard would run Northern Natural until 1991 before becoming CEO of New Jersey Resources and then Columbia Gas System (later Columbia Gas Group).

An HNG lobbyist in Washington, Terry Thorn’s business acumen allowed him to take over Enron Mojave from Ross Workman in 1987. Thorn’s plans for a PhD and academic career had stopped at the dissertation stage. An intellectual, partisan Democrat and an effective and likable boss, Thorn offered Enron a versatility that Ken Lay would utilize expertly in the years ahead.

In August 1988, Thorn became president of Transwestern Pipeline Company. About a year later, Transwestern became the nation’s first transportation-only interstate when SoCalGas nominated zero under its long-standing gas-purchase contract, choosing to buy cheaper gas than that offered by the pipeline. Gas sold by marketing companies to SoCalGas and other California customers on a monthly basis, aided by as-needed transportation-rate discounts, kept Transwestern full. The days of Transwestern as gas buyer and seller were over, but revenue was just fine, given favorably designed rate cases and growing gas demand in the Golden State.21

![]()

All of Enron’s interstates were in an expansion mode. Florida Gas’s Phase I expansion (its first in a quarter century) came on stream in 1987, and a second 100 MMcf/d expansion was planned (it would come on stream in 1991).22 After a depressed 1986, Transwestern’s throughput to California rebounded, and discounts off the maximum transportation rate lessened. In November 1989, Transwestern announced a $153 million, 320 MMcf/d mainline expansion to California, the pipeline’s first capacity increase in more than 20 years. Northern Natural, meanwhile, judiciously expanded; the Midwest was not like Florida or California, a reason why InterNorth bought HNG back in 1985.

Mojave Pipeline, a proposed interstate intended to move gas from Transwestern and El Paso to central California’s enhanced oil-recovery plants, was navigating its way through two regulatory jurisdictions: the friendly FERC and the obstinate CPUC. Southern California Gas Company, the nation’s largest gas distributor, facing bypass in its service territory for the first time in its history, was also vehemently opposed to new entry. When it came to open access, SoCalGas wanted to receive but not to give.

“SoCalGas Turns Environmentalist to Fight Rival Pipeline Companies” stated an Energy Daily headline. The article reported: “In a somewhat novel twist, [SoCalGas] has now taken up the cudgels in favor of the endangered desert tortoise and the San Joaquin kit fox,” joining such groups as Sierra Club and Friends of the Earth. Such environmental opportunism by profit-seekers would go from novel to commonplace in the years ahead, with California utilities rent-seeking via state and federal green energy programs.23

As it turned out, Mojave would merge with another expansion project and be completed in 1992, after seven years of effort and much regulatory delay, to serve central California. Enron would sell its half-interest to El Paso Natural Gas the next year.24

![]()

Together, Enron’s pipelines delivered almost three trillion cubic feet of natural gas in 1989, 17.5 percent of the national total. This compared to just above two Tcf in the industry’s depression year of 1986, a 14 percent market share. A lot of innovation and hustle went into this improvement. Among other things, GPG’s operating expenses fell by one-third (from $0.36/MMBtu in 1986 to $0.24/MMBtu in 1989), helping Enron win gas markets against oil-generated electricity and from purchased power.

Enron’s pipelines were negotiating their way out of their producer contracts, but that did not mean that they did not need sourced supply. Even if bought and sold by others, gas needed to be physically connected to the pipeline via gathering lines from the wellhead—or throughput would be short no matter how high end-user demand.

In 1987, Enron Gas Supply Company (EGS) was formed within the interstate group for company-wide gas procurement—an industry first. EGS’s 1988 goal to connect 400 MMcf/d to Enron pipes ended the year with that and 50 percent more. Claude Mullendore was president of the unit, reporting to Gerald Bennett, head of the newly created Enron Gas Services, a holding company that was also over Enron Gas Marketing.25

Thanks to advancing technology, low prices were not impeding gas supply. Better finding rates, improved drilling and completion techniques, and management efficiencies were allowing consumers to pay less and get more. “America has a large natural gas resource base that is recoverable at reasonable prices that are competitive with alternate fuels in generating electricity,” Enron’s 1989 Annual Report concluded. In fact, as documented in its periodic Outlooks, bullish Enron was right on the mark with its resource optimism—and for the right reasons.26

Capturing Gas Marketing

Federal open-access rules were transforming a key part of the wholesale natural gas business. Before, interstate pipelines could not make a margin on their wellhead gas purchases. Now, with the merchant function removed from the (regulated) pipelines, independent marketers could buy and sell gas for profit. Thus, a whole new entrepreneurial element emerged, as described in chapters 2 and 3.

It had been an eventful, productive several years since John Esslinger joined Enron Gas Marketing from Transco in August 1986. “It was starting basically from scratch,” Esslinger remembered. “I thought there was a great deal of opportunity to do marketing in a different way than it had been done traditionally,” including moving the market away from the “foolish” idea of pure spot (30-day) reliance.

EGM’s core activity was making buy-and-sell margins from its advantages of “logistics, scale, scope” and “[having] as much market knowledge as anybody,” Esslinger stated. The huge Bammel storage field (part of Houston Pipe Line) gave EGM flexibility. Strategic transportation buys by EGM provided leverage for higher margins. ECT’s reputation of fair dealing—being truly arm’s length from Enron’s pipelines even before FERC regulation required it—was important to all parties: producers, end users, and regulators.27

Bid Week was the big event each month. For three-to-five business days near the end of each month, it was all hands on the phone, buying gas here and selling it there for net margin. It began in each person’s office, but it was soon decided to create a trading pit of about 16 desks in a large conference room, making communication much easier. For the rest of the month, that space stood empty.

What were profits per MMBtu? At the time, no one knew except for a very chosen few inside the walls of Enron. Volumes, not margins, were broken out for analysts and investors having a need to know. But now it can be told. In comparison to eventual “grocery store type margins” (around 2–3 percent), earlier EGM margins could be 20 or 30 percent ($0.50–0.75 per MMBtu on $2.00–$3.00 gas).

Strict trading guidelines limited position-taking (versus back-to-back arbitrage transactions). The in-house rules were an outgrowth of the oil-trading debacle at Valhalla (chapter 4). But there was also humility. “There is just no way you can figure out the market,” Esslinger knew. With limited hedging, particularly with larger deals, going short (selling gas not yet possessed or contracted for) or long (buying gas not yet sold) was scary for the trader. Trading limits, skill, and some humility (Valhalla was still a fresh event), and maybe some good fortune too, prevented a major trading loss during EGM’s era of physical trading.

Enter Ken Lay and the art of the big deal. When new gas capacity for power generation hung in the balance (competing with coal), Enron went short on gas with its corporate credit on the line. Enron had some flexibility that competitors did not (Bammel storage for short-term deliveries and Forrest Hoglund’s EOG for longer-term supply), but the risk was buying expensive gas for its fixed-price sales commitments. Helped by wellhead prices that stayed low, Enron profitably met its long-term sales contracts.28

![]()

“Natural gas now is an industry more of marketers than it is of lawyers,” noted John Jennrich in 1988. “That’s not to say that a battalion of legal beagles isn’t needed to track down the nuances of rules from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the National Energy Board [Canada], and key state and provincial agencies,” he wrote in Natural Gas Week. “But natural gas is now a commodity—it has a price that fluctuates according to rumor, whim, cold weather, real or perceived shortages, and competing fuels.”

In 1988, EGM’s sales rose 10 percent, the slowest annual increase since inception. Yet this was almost double the volume averaged just three years before, and the bigger news was a shift toward higher-priced/higher-margin agreements with contracts running from 4 to 15 years, totaling 164 MMcf/d. “We were creating a forward market in 1988,” Jeff Skilling would remark many years later about the subsidiary he masterminded as a consultant and then ran as an Enron executive.

The year’s jewel was a 100 MMcf/d, 10-year deal with Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E), California’s largest gas and electric utility. The gas would be transported on the El Paso Natural Gas Pipeline (Transwestern did not connect to PG&E). That was the beauty of open access for Ken Lay. The government mandated that pipelines not owned by Enron were on call to EGM at nondiscriminatory rates and other terms of service.29 The new FERC-driven regime negated part of Ken Lay’s coast-to-coast, border-to-border strategy, but unregulated (intrastate) HPL and Bammel storage (now within EGM) were at the core. Government-driven open access was the enabler of EGM.

In July 1988, a regulatory change consolidated Enron’s spot-gas marketing programs into EGM. FERC’s Marketing Affiliate Rule (Order No. 497) required that interstate pipelines divest themselves of their released-gas (spot-gas) programs. Functional divorcement between transmission and commodity sales was intended to get pipelines out of the merchant function, where conflicts of interest or just preferential treatment disadvantaged independent marketers. FERC Order No. 497, in other words, was a regulatory progression from Order No. 436 and Order No. 500, illustrating the cumulative process of interventionism whereby new regulation addresses the shortcomings, the gaps, created by earlier regulation.30

With this order, PAMI (Transwestern), Northern Gas Marketing (Northern Natural), and Panhandle Gas (HPL) merged into EGM. No employee could work for both the regulated (“jurisdictional”) pipeline and the unregulated (“nonjurisdictional”) marketer. No preferential information could be communicated between the two, under penalty of law. Open access for interstates was not a free-market program but one mandated by FERC to transform the former application of public-utility regulation. It was not deregulation despite Ken Lay’s shorthand. It was half-slave, half-free: transportation regulated, gas sales unregulated, and interaction between the two once-merged functions also regulated.31

![]()

By the late 1980s EGM was a bona fide profit center, offsetting take-or-pay costs absorbed by Enron’s three interstate pipelines as they moved out of the merchant (buy and sell) function. The future looked bright with new FERC initiatives to increase the competitive arena of independent marketers, including a 1988 proposal to allow purchases of excess transportation capacity from interstate pipelines, called capacity brokering.

While EGM’s business swelled with FERC Order No. 436 declarations by interstate pipelines, as well as end users executing long-term, price-guaranteed contracts, a major constraint surfaced. Producers were not stepping up with long-term supply. A market disconnect was forcing EGM to assume nonhedged risk (really Knightian uncertainty, as defined in chapter 4 of Bradley, Capitalism at Work), by buying short-term spot gas to meet its long-term, fixed-price deals. Prices had cooperated so far by staying flat, even falling. EOG provided a backstop that other marketers scarcely enjoyed. Still, EGM could not keep playing this game. Given what happened at Valhalla, investors would sooner or later notice and penalize Enron for its growing unhedged positions.

How might EGM create a hedged long-term forward market? Gas producers were not eager to commit their future production in the wake of the take-or-pay debacle with pipelines—especially with a price keyed off (historically low) current prices. These risk-taking optimists always thought that a price rebound would be just a year or two or three away. Consequently, EGM could not simply buy long-term, fixed-price gas to mirror its sales.

Somehow, Enron had to restructure the supply side to create a vibrant, profitable market between producers and end users. This innovation would be part of Enron’s remaking the national gas market, described in chapter 8.

![]()

EGM broke out in 1989. The open-access world was maturing, gas sales by interstate pipelines were shrinking, and a national transportation grid was mostly open for business. Total EGM volumes doubled from a year earlier to 1.14 Bcf/d, reaching a peak day of 1.9 Bcf.

Spot sales increased more than 20 percent from the year before as more markets opened up and new ways of doing things, including a gas swap, were discovered.32 But the real story was “significant margin improvements … through innovative programs and other long-term sales contracts.” Long-term sales tripled to nearly 300 MMcf/d in 1989 from the prior year. Fifteen customers executed deals totaling more than 114 Bcf of annual gas sales, the largest being a 200 MMcf/d contract with SoCalGas. What Transwestern and other interstates lost in commodity purchases (on which they could not make a margin, only incur take-or-pay liabilities), EGM won with real profits.

Ken Lay’s Enron was actually profiting amid a painful transition for interstate pipelines. And once take-or-pay settlements were done, there was no reason not to make more, much more, from two profit centers in place of the previous one.

The last two months of 1989 were EGM’s best, enabled by a new program, Gas Bank. Its genesis was gas-supply dedications in the unregulated Texas market by Texas Oil & Gas (the parent of Delhi Gas Pipeline Company, where Forrest Hoglund had once presided). Its supply was partitioned into discrete what-when-where units to meet the terms of heterogeneous end-use contracts. Because these contracts were long term, calculating the related gas reserves and future deliverability was crucial. Gerald Bennett had been involved in this prior to coming to Houston Natural Gas in 1984, and it was the progenitor of a whole new concept that would later be credited to Jeff Skilling and Enron Gas Services.

McKinsey’s Skilling was tasked with creating a supply portfolio that would reduce the risk of EGM’s long-term deals to something more scalable and tailored than previously. Size and differentiation would allow EGM to cut both its price and its supply risk, locking in margins and consummating more sales.

Skilling’s innovation, with input from Bennett,33 was “nothing less than the first serious effort to diminish the level of risk for everybody involved in natural-gas transactions.” Large gas packages had to be procured and divvied into sales packages in order to meet a variety of end-user time profiles. Somewhat akin to bank deposits that could be lent for investment, these supply buckets were validated by Enron’s own reservoir engineers and then sold to end users. That was the theory of the Gas Bank, something that Skilling described much later as “pure intellectually” and as “ma[king] all the sense in the world.”

As logical and successful as the program turned out to be, the idea behind the Gas Bank was not initially embraced by Enron’s old guard. About a year before the Gas Bank hit the market, Rich Kinder called a meeting to hear out Skilling’s concept. A contingent from the interstate pipelines, led by Jim Rogers, came to the McKinsey presentation. Kinder’s Come to Jesus meeting just months before had been a victory for EGM. But questions lingered about how far and fast EGM could assume these pipelines’ well-oiled interface between the wellhead and the city gate or burner tip.

Skilling’s presentation was unexpectedly brief—one slide and less than a half-hour. The room went silent. Then Rogers spoke: “I’ve got to say, that’s the dumbest idea I’ve ever heard in my life.” Other critics chimed in, pointing out how EGM could not and should not be responsible for ensuring reliable supply. Some alligators were crawling back into the swamp that Kinder thought was drained.

After the vetting, a humbled Skilling headed back to Kinder’s office. But the boss was hardly disappointed. “As soon as I heard Rogers say it was the dumbest idea he’s ever heard, I knew it’s exactly what we need to do,” Kinder told Skilling. But really, Kinder had grasped the concept both from this meeting and from prior discussions with Skilling. McKinsey’s new marching order was to pony up EGM’s resources and make it work.

![]()

Supply in hand, Kinder and Skilling visited major gas customers interested in diversifying with some known supply-and-price quantity in addition to their shorter-term commitments. Many customers jumped at the idea of supply and price security backed by an Enron corporate guaranty. In the last two months of 1989, EGM placed 366 Bcf of 10-year, fixed-priced gas—generating income for Enron of as much as $200 million in net present value. Such profit required gas streams backed by good reservoir engineering and the requisite long-term transportation to the delivery point, something that mandatory open access enabled.

But the success came with concerns. First, the long-term gas was not hedged. Only if prices stayed down (they would) would the margins be large. The other problem was a depleted Gas Bank. Low wellhead prices and scarce bank financing in the wake of the energy-price collapse of several years were limiting the product that end users wanted. A new generation of supply-side product was needed. And that required an innovative leader to engineer new approaches to the business—and to construct the institutional architecture that would turn ideas into action.

As 1989 drew to a close, Rich Kinder and Ken Lay asked Jeff Skilling to join Enron. But the 36-year-old had just been elected partner at McKinsey with a salary that Enron could not match. Enron was a bird in the bush, not the hand. Skilling was not quite ready to stop being a schemer, the outside set-up man for the most innovative gas company anywhere. Moreover, consulting fees paid to McKinsey by a continually reorganizing, reanalyzing Enron were huge.

Liquid Fuels: Profitable Incrementalism

Enron Liquid Fuels (ELF) had the lowest profile of Enron’s major divisions. It was not sexy like exploration and production, where each new prospect brought suspense and potential riches. Unlike the interstate pipelines, ELF did not operate in a regulatory maze where industry news was made with FERC filings and Rogers speeches.

ELF wasn’t an upstart like EGM, blazing new territory and making history along the way. No, it was relatively quiet business to turn natural gas into ethane, propane, butane, and gasoline; pipe these liquids around the Midwest and Southwest; and trade liquids or petroleum. For Ken Lay, this midstream was not too exciting but integral to Enron’s natural gas model.

ELF’s Mike Muckleroy had gotten rid of most of the top managers he inherited from InterNorth, including all five division presidents. Their replacements all had been found internally. InterNorth was like that; middle managers could often be as good as or better than their tenured superiors.34

Best of all, ELF went from net losses in 1986 and in 1987 to income before interest and taxes (IBIT) of $58 million in 1988 and $89 million in 1989, the last figures being between 10 and 15 percent of Enron’s total. Reorganizations and a major reduction-in-force in late 1988 were part of the turnaround.

Strong margins in liquids had formerly depended on high selling prices. But in a low-price environment, profitability was about controlling cost, value-adding services, and marketing. That is where the affable Muckleroy earned his keep. He liked to find out where the problems were and get out in front of them. He led by example, regularly walking the floors to talk to people and inspire them to do a little more—and be rewarded for it. He was considered close to ideal by his thousands of employees.

![]()

When Ken Lay reset Enron’s sights as a global natural gas company, ELF provided a platform as the world’s sixth-largest nongovernmental marketer of liquid products. With major offices in the United Kingdom, France, and the Netherlands, international opportunities were expanding, in part from the growing US position as a net importer of petroleum and gas liquids. “Demand for natural gas liquids continues to grow worldwide while supply is abating domestically,” Enron’s 1989 annual report stated.

With a growing linkage between foreign and domestic markets and a forecast that ELF’s foreign side would be a net product provider to the United States, Muckleroy merged Enron Liquid Fuels International into Enron Gas Liquids in 1989. Five divisions were now four—Enron Gas Liquids; Enron Oil Trading & Transportation Company; Enron Gas Processing Company; and Enron Liquids Pipeline Company.35

Muckleroy found out how hard it was to operate in noncapitalistic parts of the world or where a joint venture was lacking parental attention or where the operation was distant and obscure. For example, Enron and GE jointly owned a Venezuelan manufacturer of GE appliances—Madosa—which turned into a money drain, in part from a bad economy and also from government controls. Small investments in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic were or would be problematic as well.

Some success came from just being able to say no. A case in point was when Muckleroy inaugurated a meeting between Ken Lay and the Russian Minister of Energy, which resulted in a highly publicized letter of intent in December 1989 for Enron to develop a full range of natural gas projects there. But Muckleroy knew better than to make investments in unstable, unpredictable jurisdictions. What ELF did do was enter into a marketing agreement for refined products whereby Russian deliveries were paid for only when they reached Baltic ports. It was profitable, and Ken Lay had gotten his photo op.

Muckleroy also stopped short of making capital-intensive investments in LNG infrastructure. Prior to its merger with Houston Natural Gas, InterNorth had taken a big hit when it had to cancel an LNG tanker order. ELF left the big infrastructure projects to those companies with time-honed expertise. Muckleroy was sufficiently risk averse to stick to his knitting, and there was plenty to do, given ELF’s economies of scale and scope. Such prudence would be missed at Enron a decade later when Muckleroy and other experienced executives like him were gone.

In 1989, ELF acquired CSX, Louisiana’s largest gas-liquids processor. In the same year, contracts were executed to build a 100-mile, 30,000 bbl/day ethane pipeline from Mont Belvieu, Texas, to Lake Charles, Louisiana. Although its $55 million capital budget for 1990 was down from 1988’s $89 million, ELF was one of Enron’s Big Five divisions heading into the new decade.

![]()

With ELF and EGM, Enron offered customers an entire portfolio of energies at a variety of prices for periods from one month to multiple years. No other company could do this, Ken Lay proudly pointed out. Even on the petroleum side—which Lay would not emphasize—ELF described itself as “a fully integrated crude oil entity in North America.”

Trading was part of ELF, but it was not speculative like at the old Enron Oil Corporation. Betting on future price movements was quite secondary to trading around the company’s hard assets. Traders who violated ELF’s strict limits “fired themselves,” as Muckleroy put it. One who did, ironically, had come down from Valhalla where, unlike some of his colleagues there, he had played by the rules.

Mike Muckleroy, Valhalla hero and company builder, was rewarded in 1989 with total compensation near $1 million. He was Enron’s third-highest-paid executive after the chairman and the vice chairman. In December 1989, Muckleroy entered into a new five-year contract with an increase in minimum base pay. To the board and Lay and Kinder, he was a man to keep.

Getting Political

Enron’s profit centers in the 1980s were particularly, even uniquely, tied to federal energy policies. FERC regulated the interstate pipelines with complicated rate cases affecting the difference between authorized and actual rates of return. PURPA drove independent cogeneration to create a competitive arena for nonutility providers. Mandatory open access enabled gas marketing on interstate pipelines. And Forest Hoglund’s EOG was lobbying to get a tax break that would contribute to a roaring 1990s.

But there was another political card to play for natural gas–oriented Enron. Coal gained the upper hand on natural gas as an unintended consequence of federal policy in the 1970s. Price controls on natural gas, specifically, created shortages that turned electric utilities to abundant, non-price-controlled coal. On the belief that natural gas was geologically constrained rather than governmentally discouraged (“we had a surplus of regulation, not a shortage of gas,” Lay would say), federal law instructed industries and utilities to substitute coal for gas in new facilities.36

Even in the face of gas surpluses, coal interests continued to disparage natural gas as unreliable—something that caught in Ken Lay’s craw. There was public relations work to do—such as rebutting the anti-gas rhetoric of Richard Lawson, president of the National Coal Association. More important, there was Enron’s marketplace rejoinder with the Gas Bank and other innovations that reduced price and supply risk to clinch the economics of gas plants relative to coal plants.

Natural gas had another card to play against coal: less pollution per kilowatt hour of electricity produced. A table in Enron’s 1988 annual report showed these reductions for a gas-fired power plant relative to a coal facility: 99 percent for sulfur dioxide (SO2); 43 percent for nitrogen oxide (NOx); 53 percent for hydrocarbons; and 96 percent for particulates (PM10). These were traditional, criteria pollutants as defined by the Clean Air Act of 1970 and subsequent legislation. In addition, the table identified a 48 percent reduction for natural gas relative to coal in electric generation for the major manmade greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide (CO2). CO2 was not a pollutant in the classic sense but a heat-trapping gas that contributed to global warming (aka climate change), other things being equal. This became a national issue in the hot, dry summer of 1988 when NASA scientist James Hansen testified before a Senate subcommittee chaired by Al Gore (D-TN). “Global warming is now sufficiently large that we can ascribe with a high degree of confidence a cause and effect relationship to the greenhouse effect,” Hansen testified.