13 Implementation of a cluster based local development strategy

Abstract

Processes of clustering and initiatives to promote the creation of clusters have become an important issue in regional business development policy in recent years. The concepts can be traced back to the classical notion of industrial districts, and the embedded mechanisms and features causing superior economic performance ascribed to firms within the districts. In the last decades the concept has become increasingly popular in regional and local business development policy. This chapter provides a comparative assessment of cluster initiatives in two medium sized city regions in very different economic settings, Sønderborg in the southern part of Denmark, located close to the German border, and Eau Claire in Western Wisconsin, USA, as well as identifying the impact of cluster promoting policies in these settings.

The aim of the analysis is to identify policy instruments and to compare the implementation and economic impacts of cluster promoting policies in a different economic and structural setting. Despite differences, both regions also have similarities, facing severe challenges from economic restructuring with loss of traditional blue colour employment and the transformation of the local economy toward service and IT-based activities. The central research question is to identify cluster related instruments, to compare the policy set-up in the two areas, and analyse how they interfere with the general economic development concepts of the country, state or region.

The findings show that, on account of different traditions and economic institutions, significant differences in the policies are identified. One of the major aspects appears to be the level of commitment to a cluster development policy in both regions (Southern Denmark and West Central Wisconsin). In Denmark this approach has brought together more entities resulting in a more comprehensive and better funded policy effort. In Wisconsin, the cluster policy to economic development is very recent, has been poorly structured and is highly sensitive to political changes. With regard to the used instruments and measures, similarities are present, i.e. the focus on knowledge and innovation, often conducted within a ‘triple helix’ framework. Macro level impacts have, due to the limited financial resources, only been visible in certain local areas.

Introduction

Concepts and approaches to regional development have undergone significant changes in the last decades from growth pole oriented concepts to policies based on endogenous potentials, entrepreneurship and innovation stimulating initiatives on the local and regional scene (Audretsch, 2006; McCann, 2008). Common for all of them is an attempt to copy environmental conditions which have been favourable to generate economic growth and competitiveness in other regions. Among the most popular strategies in recent years are initiatives to promote the development of clusters. The cluster concept can be traced back to the classical notion of industrial districts, and the embedded mechanisms and features causing superior economic performance ascribed to firms within the districts.2 Regardless of the fact that the archetypes of successful clusters or industrial districts are either historic, e.g. the Marshallian examples from England and the classical Italian districts, or are linked to specific framework conditions which can hardly be copied elsewhere, like Silicon Valley, clusters are a component in most current regional and local business development programmes. The typical successful cluster or agglomerated industry is characterized by a location in metropolitan regions or at least regions with larger urban centres like ‘Medicon Valley’ in the Èresund region, the ‘Cambridge corridor’ in England or the ‘machinery cluster’ in Baden Württemberg in Germany. Nevertheless, less urbanized regions with a less specialized industrial structure have launched cluster strategies to promote regional development.

The aim of this analysis is to clarify under which conditions a cluster-based development policy seems to be a realistic and fruitful policy option, and what type of instruments are needed. In continuation of this, the purpose is to identify and compare the implementation and economic impact of cluster promoting strategies in two non-metropolitan regions with lower endogenous potentials than available in central regions, and which supportive measures, public or private, are necessary for a successful implementation of the cluster strategies. The chapter is built on a comparative assessment of two medium sized regions in very different economic settings: Sønderborg, in the southern part of Denmark, located close to the Danish-German border, and the Eau Claire area in Western Wisconsin, USA. Analytically, the analysis is focused at the regional/state level and at the local municipality/county level.

The remainder is organized as follows. The next section provides a brief overview of the theoretical and empirical foundations of industrial districts and clusters with special attention drawn to the mechanisms facilitating economic growth and competitiveness. Then the following section aims at a comparative analysis of cluster strategies in two very different regions in order to identify and compare the implementation and economic impact of these cluster strategies. The analysis ends with a conclusion where implications for further research are stated.

Theoretical foundations

The aim of this section is to summarize the most important theoretical arguments behind the, presumably, positive forces at work in clustered industries, and how these conditions might be duplicated by a targeted business development policy. Aimed at strengthening the ability to improve economic performance and competitiveness, the creation of a ‘cluster or industrial district’ type of business environment has become a central means in the toolbox of regional economic development:

There is currently a strong belief in many countries and regions that clusters can be the major vehicle for economic development and growth. If this belief is correct, it is certainly important to contemplate which model to apply in practical policy work. The question relates to the implications of the different models and how they can and should be used to guide the formulation and implementation of cluster policies.

(Karlsson et al., 2005: 2)

In this context it is important to differentiate between types of clusters3 and industries (i.e. manufacturing, traditional service or knowledge-based activities) and the size of the agglomeration or region. Central in this application of the cluster concept in an economic growth and development context is to take the characteristics of particular clusters and traditional industrial districts into consideration. According to Gordon and McCann at least three different types can be distinguished (Gordon and McCann, 2000: 515–21): the classical agglomeration based model, an industrial-complex model, refers to, in particular, commercial relations between companies and social network models focusing on trust and social relations. The latter can become particularly important for the understanding and implementation of a network based economic development policy:

But, where the development of the social network is associated with the development of a place-specific industrial cluster, it is possible to view this model as exhibiting some of the characteristics of each of the two previous models of spatial industrial clustering. For example, the social network allows many of the external benefits to be internalised within the group, as in the case of the complex, although some of the benefits may be capitalised into local rental values, as in the case of a pure agglomeration.

(Gordon and McCann, 2000: 521)

Nevertheless the central factor is the nature of systems of production with regard to regional and/or functional characteristics, the institutional set-up of a system as a supportive measure for cluster policy. The latter is particularly important in the broader concept of clustering used in recent studies of the performance of clustered industries and regions focusing on the presence of clusters or geographic concentration of industries linked together. According to Porter (2003: 562), a cluster is defined:

as a geographically proximate group of interconnected companies, suppliers, service providers and associated institutions in a particular field, linked by externalities of various types…. Clusters are important because of the externalities that connect the constituent industries, such as common technologies, skills, knowledge and purchased inputs.

It is important to note that Porter explicitly stressed that an industry can become a part of several clusters, which can cause problems in the empirical assessment of cluster performance (i.e. with regard to employment). From a conceptual point of view the issue is solved by a distinction between narrow and broad cluster definition. The former is based on the strongest geographical and location ties of a particular industry. Broad clusters include all industries in the cluster (Porter, 2003: 563). In this sense, a cluster shares many features with the more general concepts of production systems or innovation systems. It can be questioned whether the geographical precondition is necessary, or whether it is possible to take advantage of the potentials of positive pecuniary externalities ascribed to clusters or industrial districts in a spaceless or virtual context, in particular when dealing with clusters of the third category (the social network type) mentioned above.4 Globalization and outsourcing have led to changes in the production system in original clustered industries with significant and often dominant production taking place outside the geographical cluster. However, firms in the clusters often remain at the core of the value chain and become engines of commercial growth and industrial renewal. From a knowledge and innovation point of view, the crucial issue remains: to what extent will companies be able to exploit the positive externalities ascribed to clustered production systems in a virtual world where the social and tacit knowledge becomes less accessible and maybe will disappear?

From a policy point of view the task is to create conditions facilitating the dynamic development of the industrial clusters, to support the transition of the value chain. This has to be done by taking the regional context into account, which means the locational dimension of clusters or industrial districts.

A core element in a cluster-based policy is to facilitate for the policy to take the nature of clusters into consideration, i.e. co-location of firms and other relevant actors. Furthermore, the dynamics of cluster development are crucial to take into consideration, i.e. the cumulative path-dependent evolution of the process and the possibilities to create location advantages by policy measures (Karlsson et al., 2005: 13). Finally it is important to take the lifecycle of clusters and the relationship between (competing) clusters into consideration. The former is closely related to technology and innovation which can make cluster advantages obsolete, the latter can cause competition for factor inputs in a particular region from other, faster developing, clustered industries or individual companies. These aspects are of significance in relation to a cluster development perspective, since cluster supporting policies are not usually green field investments but based on existing endogenous and relational potentials.

Figure 13.1 sketches principal actors and entities in a development set-up based on a cluster development strategy embedded in a ‘triple helix’ cooperation framework. With regard to the Danish case (presented in the next section) the role of a large anchor company within the cluster area is of particular importance. This leads to the central issue addressed: how, and to what extent, are the policy options in regional development agencies determined by the real economic environment, or the institutional and political framework in a given society? The remaining part of the chapter will shed some light on this based on two regions in very different settings.

Empirical evidence: two case studies

Policy applications of cluster concepts often highlight the intangible aspects of clusters and industrial districts rather than focusing on the more mixed empirical evidence of the better performance of business and industries located in or adjacent to a cluster (see Engelstoft et al., 2006). This view is often supported and reinforced by the fact that policy instruments in particular can affect these components, i.e. the triple helix related activities highlighted in the previous section.5

Clusters can be defined in many ways; for an overview, see Karlsson (2008) with different focal points. In an analysis with focus on economic development and the impact of clusters on economic performance, it is important to distinguish

Figure 13.1 Cluster entities and relations.

Source: Cornett and Ingstrup (2010: 58), based on Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff (2000).

between different types of clusters and the economic performance of the involved industries or sectors. This calls for a profound assessment of the potential of a cluster-based policy and its limitations. An attempt to develop a principal classification related to economic performance and location and the above mentioned issue of clustering is sketched in Figure 13.2. The main purpose of the classification is to stress that clusters are not always beneficial for a particular region’s development prospects, but that the positive potential depends on the sectoral or industrial affiliation.

Figure 13.2 distinguishes between four (eight) principal outcomes. With regard to the cluster perspective, the first and the second quadrants are of special importance. Regions with clusters characterized by positive change in the location quotient in a good performing sector have the best development perspective. Regions with industries in quadrant II are less well off in a cluster perspective, but at least they are not threatened by economic decline because of poor performance of industries belonging to mature or shrinking clusters. In this case, a low location quotient does not indicate a disadvantage; rather the contrary from a development point of view. These regions will probably benefit the most from a proactive cluster development policy.

Figure 13.2 Advantages and disadvantages of clustered industries.

Note: The location quotient is defined as share of local employment in industry divided by share of national employment of industry. As a proxy to change in production value, the change in employment is used in the empirical section due to data availability.

The situation in quadrants III and IV is more complex. The former indicates that a region has a lower density of the most promising industries, and that an active cluster promotion policy could make sense to stimulate existing firms as cores for new, emerging or potential clusters (see Cornett and Ingstrup, 2010: 52–4). Quadrant IV represents the classical case for economic restructuring in a region with a declining and outdated industrial base, in a cluster perspective. The sketched classification of clusters in a development potential perspective in Figure 13.2 gives a first hint for the prospects of a cluster-based regional development strategy, anchored in the existing industrial base. The following two case studies aim at providing empirical insight into regional development initiatives, at least partly based on tools directed at the creation of a business environment providing some of the conditions often attributed to clusters or industrial districts in the literature.

Eau Claire and West Central Wisconsin

The first area of interest is the Eau Claire Metropolitan Statistical Area (Eau Claire MSA) located in West Central Wisconsin. It is made up of two counties – Eau Claire and Chippewa – and consists of about 150,000 people. The city of Eau Claire, population 65,000 people, is the primary city.

Eau Claire, in the confluence of two rivers (Eau Claire and Chippewa), started as a lumber town in the nineteenth century. The advent of the automobile provided the impulse for other activities such as tyre production. Chippewa Falls was the site of one of the very first tyre making plants and in 1917 Eau Claire became the home of a tyre plant, which quickly became the largest employer and the backbone of the local and regional economy. The plant, under different ownerships – Gillette Safety Tire Co., United States Rubber Co., and Uniroyal Goodrich Co. – closed in 1992 and left Eau Claire scrambling for solutions. The large labour pool combined with transportation advantages – the easy access to the Interstate Highway System, the presence of a regional airport and railway – as well as an aggressive campaign by local economic development officials successfully attracted new businesses such as Hutchinson Technology Inc., a computer parts manufacturer that created 1,400 jobs, marking a new era for Eau Claire. It helped that Chippewa Falls was the hometown of Seymour Cray and the site for Cray Research, the first supercomputer company, later acquired by Silicon Graphics (SGI). In addition, this area has also developed into a major retail trading centre and a regional medical and educational centre. Eau Claire is home to the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire and the Chippewa Valley Technical College.

Economic and institutional structure

The Eau Claire MSA is now home to a vibrant high-tech community, while still holding on to remnants of its rich economic past creating an interesting and unique mix of businesses and industries as shown in Table 13.1. Over the last ten years the industries that have grown fastest include natural resources and mining as well as services like financial activities, professional and business services, education and health services, and leisure and hospitality.

Figure 13.3 illustrates the relationship between the location quotient (LQ) and the rate of growth in employment in these industries. Deller (2010), in Porter’s tradition, suggests that industries in quadrant I (strong) and quadrant II (weak), which are growing in terms of employment, are potential clusters for economic growth and should be the focus for economic targeting efforts.

Industries that have experienced negative changes in employment, such as manufacturing, trade, transportation and utilities, construction, and information might have been hit harder by the Great Recession. Employment is the variable of choice to measure economic activity because of data availability. The US Economic Development Administration has adopted Porter’s cluster approach and has provided many tools based on employment. This data is also available at the county level and for metropolitan statistical areas, allowing for easy and convenient comparisons.

It may be of interest to disaggregate these sectors for a better picture, particularly in manufacturing, which still accounts for about 16 per cent of employment in the Eau Claire MSA. Data is available for super-sectors (highest aggregation level) as shown in Table 13.1 and Figure 13.3, as well as for sectors (two-digit level) and

Source: Based on data from US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Note: Bubble size represents relative importance of the industry in terms of employment (2009).

Table 13.1 Employment in the Eau Claire MSA for the period 2001–09

Source: US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Labor Statistics (2010).

sub-sectors (three-digit level). The industry coding used is the 2002 version of the North American Industrial Classification System. Sectors with relatively high LQs for 2009 are: retail trade (NAICS 44–45) with 1.18; health care (NAICS 62) with 1.26; management for companies and enterprises (NAICS 55) with 1.73; and finance and insurance (NAICS 52) has an LQ of 1.13.

The geographical distribution of industry concentrations in West Central Wisconsin is outlined in Figure 13.4. This map, published by the West Central Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission, one of several federal level commissions in the state, is based on industries with more than 100 employees in the region. It excludes concentrations for government, public schools, retail, financial and business service.

An analysis of changes in both LQs and employment data suggests that food, paper and plastics, three well established clusters in the area as well as in the region and state (Wisconsin Paper Council, 2003), appear to be declining in terms of employment. However, given the relatively small changes in employment and the 2008 recession, it may be premature to draw any far-reaching conclusions. On the other hand, fabricated metal, printing and beverages appear to be growing stronger. Furthermore, in the area of services there appears to be an emerging

Figure 13.4 Industry concentrations in West Central Wisconsin in 2007.

Source: West Central Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission (2009).

cluster in professional and business services, namely in the area of management of companies and enterprises.

The Organizational Set-up of regional development policy in the state of Wisconsin (see Figure 13.5) was originally headed by the Wisconsin Department of Commerce (DOC), now transformed into the Wisconsin Economic Development Corporation. At the national level we have the US Economic Development Administration (EDA), an agency within the US Department of Commerce (USDOC) created 45 years ago, which has six regional offices. Wisconsin falls under the umbrella of the Chicago Regional Office, along with several other Midwestern states. In Wisconsin alone, the EDA has seven Regional Planning Commissions which coordinate the federal and local planning efforts.

The Eau Claire and Chippewa counties fall under the West Central Regional Planning Commission, along with Barron, Clark, Dunn, Polk and St Croix counties. Another regional economic development organization serving West Central Wisconsin is Momentum West, which promotes economic development in a region composed of ten counties including Eau Claire and Chippewa.

At the county level, the Eau Claire MSA is home to two non-profit economic development organizations funded by public and private sources – the Chippewa County Economic Development Corporation (CCEDC) and the Eau Claire Area Economic Development Corporation (EDC). At the city level, and serving the city of Eau Claire, there is an Economic Development Division, which is credited with much of the local economic development success over the last two decades. There is cooperation between the Eau Claire Area Development Corporation and the city of Eau Claire Economic Development Division as to avoid duplication of efforts.

Cluster strategies and programmes

The US Council on Competitiveness published a report in October 2001 promoting clusters as a competitiveness and innovation enhancing strategy. In 2002, the National Governors’ Association, in turn published A Governor’s Guide to Cluster Based Economic Development in which they outlined their policy recommendations to support competitive clusters under the following categories: 1) organize and deliver government-supported services to clusters; 2) target investments to clusters; 3) strengthen networking and associative behaviour; and 4) develop human resources for clusters (National Governors Association, 2002).

The EDA has funded research on clusters during the last two decades and has compiled a series of best practices and tools available to state and local economic development agencies. They also administer a series of economic development assistance programs, including Revolving Loan Funds (RLF). Presently, the EDA is promoting the so-called Regional Innovation Clusters (RICs) initiative. RICs are defined as ‘geographic concentrations of firms and industries that do business with each other and have common needs for talent, technology, and infrastructure’ (US Department of Commerce, 2011).

Clusters, from EDA’s perspective, typically cross political boundaries (representing the ‘economic’ region), and include related or complementary businesses, with active channels for business interactions and that share specialized infrastructure, labor markets, and services. Moreover, such regional clusters draw on the expertise of local universities and related institutions to serve as centers of innovation and drivers of regional growth, building upon the region’s unique competitive advantages through the promotion innovation and entrepreneurial activity.

(US Department of Commerce, 2011)

The Federal Government’s role is to help self-organizing, bottom-up RIC participants by identifying (but not creating) existing RICs, convening stakeholders, providing a framework to support networks of clusters, disseminating information, and targeting capital investments. Some of the recommendations include: a bottom-up approach, involvement of private and public partnerships at all levels (i.e. local, regional, state and federal), building unique clusters on the basis of local strengths, and linking with relevant external efforts (including regional economic development partnerships and cluster initiatives in other locations).

The fiscal year 2010 budget allocated $50 million to the EDA to support clusters: first by developing a national research and information centre to begin mapping clusters to assist economic development practitioners, and, second, by developing a comprehensive competitive grant programme to promote cluster efforts across the country. Implementation support for cluster programmes could be conducted through the agency’s existing economic development assistance programmes, but it would be more effective if it could be linked to targeted clusters identified through research.6 At the state level, the state of Arizona is generally seen as the leader in cluster economic development, but other states, including Minnesota, Iowa and Wisconsin, have also targeted clusters in their recent economic development efforts.7

In Wisconsin, two major economic development initiatives were formulated in the last decade: Governor Doyle's ‘Grow Wisconsin’and the Wisconsin Technology Council's Vision 2020: A Model Wisconsin Economy.8 Vision 2020 is based on three core ideas: building Wisconsin's technology clusters, establishing research centres of excellence, and creating an institute for interdisciplinary research. These technology clusters were conceived as community based, private sector driven, with a core of 10–15 independent public and private businesses, surrounded by 10–12 small emerging companies, led by 1–3 anchor companies, and supported by local angel networks and local legal, financial and consulting services. The defining feature of these clusters is their connection to a research centre of excellence. These research centres, in turn, would link the clusters to the institute for interdisciplinary research, which would develop plans and strategies for Wisconsin. Vision 2020 identified the following four potential state-wide clusters in knowledge-based industries: healthcare, workforce education, media and design, and information and data management.

The Wisconsin DOC (2003), on the other hand, identified seven established clusters state-wide (dairy, food products and processing, paper, plastics, printing, small engine manufacturing and tourism) and three emerging clusters (biotechnology, information technology and medical devices). It pledged to support those eleven clusters by funding cluster-specific programmes, promoting the creation of cluster councils, such as the Wisconsin Paper Council, and identifying industry leaders that would act as ‘champions’. Commerce staff members were appointed as ‘cluster coordinators’to work together with the industry champion and other relevant stakeholders.

Later, small engine manufacturing was dropped from the list of established clusters and replaced with wind energy, and biotechnology moved into the established category according to Forward Wisconsin (2011), a non-profit corporation founded in 1984 on the recommendation of the Governor's Strategic Development Commission, whose mission is to market Wisconsin as a location for out-of-state businesses.

At the regional level, Momentum West hired a consulting group in 2008 (GSP Consulting Corp.) to conduct a technology, talent and target industry assessment study for West Central Wisconsin. This study identified the following regional clusters: emerging sectors (bio-agriculture, bio-energy and sensors), existing sectors (computers and electronics), supporting sectors (medical devices, plastics and packaging healthcare and education) and enabling sectors (chemicals and nanotechnology).

At the local level there are no cluster-specific initiatives, but in the Eau Claire MSA there are initiatives that promote collaboration and clustering, such as industrial parks and various public and private partnerships between businesses, local government and educational institutions. Public and private partnerships are at the core of the city's development, as illustrated by loan consortiums of local lending institutions and industrial parks. The city of Eau Claire has four industrial parks, two of which are partnerships between the city and Xcel Energy, the local and regional energy provider9 (Gateway West and Gateway Northwest), one is wholly public owned (Sky Park) and one is totally private (Chippewa Valley Industrial Park). These industrial parks cater to different types of businesses, clusters in a broader sense. The Eau Claire Area EDC was instrumental in forming the Gateway Industrial Park Corporation with the City of Eau Claire and Xcel Energy. It served as the original manager of Gateway Industrial Corporation and coordinated large acquisitions of parcels. This was a very important example of successful collaboration that helped this area at a difficult time. In addition, the Eau Claire MSA's educational institutions have long collaborated with the business community (and the community at large) in many different ways. Important initiatives include the NanoRite Innovation Center at the Chippewa Valley Technical College and the Materials Science Center at UW-Eau Claire. The NanoRite Center is an incubation centre that caters to businesses, both startups and well established, in the areas of micro-fabrication and nanotechnology. Local business partners include MN Wire and OEM Micro. The Materials Science Centre offers state-of-the-art instrumentation and researchers’expertise in the fields of materials characterization, microscopy and elemental analysis to promote industrial research and development in this region.

Sønderborg, ‘the border triangle’and the region of Southern Denmark

The Sønderborg area, is here defined as the recently founded new municipality of Sønderborg based on the city and six previously independent municipalities in the vicinity. The municipality and town are located on the island of Als and Southeast Jutland around the Als sound. The area has a long industrial history, with a particular stronghold in machinery and electronic equipment, etc. (see Figure 13.6) also forming the base of the recent cluster development strategies.

Historically, the industrial and commercial development of the area in the last 50 years was influenced to a large extent by the Danfoss company, located approximately 30 km northeast of Sønderborg, and spin offs from the firm. The company (one of the largest manufacturing firms in Denmark) has notably served as an industrial and commercial anchor of development in the region, (compare with Figure 13.1), and has also actively taken part in the overall development of the industrial and general knowledge infrastructure of the area.

Economic and institutional structure

The set-up for the local and regional business development systems in Sønderborg follows the general pattern in Denmark. The local activities are organized in a separate unit with close ties to the municipality, and in particular the committee for culture and economic development. Currently, the operational entity is named Centre for Business and Tourism Development, a merger of two former independent agencies.

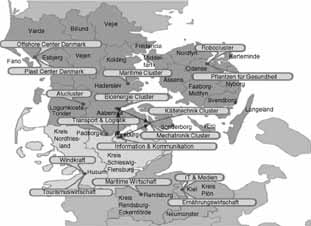

Figure 13.6 The regional business development environment growth forum and its partners of cooperation.

Source: Adapted from Danske Regioner and Kommunernes Landsforening (2007).

The units are partly responsible for local initiatives and partly they act as coordinating and counterpart units for the regional initiatives organized by the so-called ‘growth forum’, the regional cornerstone for economic development policy. See Figure 13.6 for a summary of the main features of the business development set-up in Denmark.

The dependence on the general and regional Danish setting is supplemented by local cross-border initiatives partly supported by, and integrated in, the Danish-German EU cross-border ‘Interreg programmes’. Locally, the so-called ‘border triangle’cooperation (see Figure 13.7) founded by the municipalities of Flensburg in Germany and Aabenraa and Sønderborg in Denmark is of importance in the current context. In a cluster and regional development perspective, the cooperation between knowledge institutions and business development agencies across the border constitutes an important building block in a local triple helix set-up, facilitating the existing and emerging clusters, (see also the next section).

Overall, the development of the local labour market has been stable from the late 1990s until the financial crisis, but significant structural shifts have occurred, weakening the traditional manufacturing strongholds in the area, a tendency reinforced by the financial crisis (see Table 13.2). Recently also, public sector employment has been affected by the tighter budgets.

The main challenge for the future to cope with is that most, if not all, lost low-skill blue collar employment will not return even after an economic recovery,

Figure 13.7 Clusters in the border region South Denmark Schleswig-Holstein and ‘border triangle cooperation’.

Source: Region Sønderjylland-Schleswig, Syddanmark Pendlerinfo (2011).

and that the knowledge-based strategy will not solve the short and medium term unemployment problem in the local area as well as the country as a whole.

The strongest asset for the Sønderborg region, from a development perspective, is that much of the employment reduction took place within companies with a broader skill and competence base, and with good potential to recover, as recent economic accounts have shown.

Traditionally, regional business development policy was the responsibility of the counties in Denmark, who were also in charge of cross-border cooperation. Now the responsibilities are shared between the region and the municipalities leading to a more dispersed configuration of interests, which can cause potential policy conflicts since business development initiatives cannot usually be limited to a certain administrative defined area. This is of particular importance in the field of cluster development since many initiatives can be dated back to the former counties. Furthermore the relevant business environment is larger than the newly formed municipalities, with important linkages to the surrounding economy.

The two illustrations in Figure 13.8 summarize the situation in cluster relevant sectors and industries before the current initiatives took place, i.e. high employment service sectors and sectors in emerging and new technologies. Compared to

Table 13.2 Employment in New Sønderborg municipality since 1997 (workplaces)

Source: Danmarks Statistik, Statistikbanken (2011).

Figure 13.8 Strong and weak industries in Southern Jutland (1992–2001).

Source: Monitor Group analysis, here quoted from Martens (2008).

Figure 13.8 Continued.

the region of Sønderjylland, the situation in these sectors overall is better in the Sønderborg area.10

As indicated in Figure 13.9, the Sønderborg area has in particular a national stronghold in electronics and electric equipment, both central in the two most prominent local cluster initiatives, mechatronic and cooling.

Cluster strategies and programmes

In order to support the strongholds and cluster activities described above, a range of cluster policies at national, regional and local levels have been implemented in Denmark. For the most part, the cluster policies have been implemented at the regional level but within the boundaries of a larger national policy framework. The conjunctions of this national policy framework go back to the early 1980s when a number of studies regarding industrial complexes and knowledge distribution in innovation systems were made (Drejer et al., 1999). The objective of these studies was, in particular, to identify and describe the competitive stand and

Source: Danmarks Statistik, Statistikbanken (2011).

Note: the large change from 2008 to 2009 in electronics and electric equipment is probably on account of an organizational split up in a large company.

structures of the Danish economy. In the wake of this, Michael Porter conducted a study in the mid-1980s, in ten nations, including Denmark, in order to explore the competitive advantages of these nations and the circumstances causing their competitiveness. The study showed, among other things, that Denmark had five clusters: a shipping cluster, a technical cluster, a pharmacy and biotech cluster, an agro-food cluster and a mink cluster (Porter, 1990). These findings stressed the importance of clusters for the Danish economy, and started a general debate about the competitiveness of Danish firms and how to strengthen their competitiveness for the benefit of the economy in general (Drejer et al., 1999). One of the outcomes of this debate was the definition of eight, later lowered to six, resource areas or meta-clusters on which Denmark should focus its industrial policy. The six resource areas are: food, consumer goods and leisure, construction/housing, communication, transport and supplying industries, and medico/health.

The mapping and definition of these six resource areas back in the 1990s have been one of the few attempts to set up national meta-clusters and formulate related cluster policies. But it was first with the establishment of the five regions in Denmark and their growth forums in 2007 that clusters and cluster policies were truly and intensely dealt with in Denmark. The regional cluster policies depart, among other things, from the national policy framework mentioned above but they are also inspired by a number of national and regional cluster policies around Europe. In the case of the region of Southern Denmark, which includes the cluster activities in Sønderborg and the border triangle region, the cluster policy draws to a great extent on the experiences and learning from the Norwegian NCE cluster programme (Ingstrup et al., 2009). Besides that, a number of cluster studies and cluster mappings have added to this base of experience, and all together it constitutes the policy platform from which the cluster efforts and activities in the region of Southern Denmark are embedded.

Based on these experiences, the cluster policy in the region of Southern Denmark, which is integrated in the regional business development strategy, stands on three pillars: a dominating bottom-up approach to cluster development, a life cycle perspective on clusters, and a triple helix platform. These pillars form a base for all of the cluster policy initiatives launched and they are believed by the regional policy makers to promote strong and competitive clusters. Indeed, the goal of the regional cluster policy is to create 15 per cent value added growth within existing clusters and to create 15 per cent more jobs in new potential clusters (Syddansk Vækstforum, 2009). To meet these goals, the region of Southern Denmark has invested around 220 million DKK, from 2007–10, in cluster development and it has put forward several support programmes, including financial support programmes and those for improving cluster facilitation and cluster cooperation. So far, most of these efforts have been directed towards supporting the growth of potential and emerging clusters in the region, but top-down initiatives to launch a food cluster, a transportation cluster, an energy cluster, and a welfare-tech cluster have also been taken, combined with a range of other projects, such as the establishment of REG X, which is a national centre for cluster development, and the Southern Jutland based initiatives, including the border triangle initiative.

Similarities and differences

For the Eau Claire case we can conclude that despite the efforts that went into formalizing a cluster centred development strategy, the state failed to follow through on key recommendations and it is now apparent that the cluster strategy has not been successfully implemented (Hefty and Torinus, 2009). This failure is acknowledged in the Strategic Plan released in March 2011 to convert the Wisconsin DOC into the Wisconsin Economic Development Corporation (WEDC). It states under Strategy 4, ‘Implement a focused target industry advancement capability’:

Too often, target industry or cluster initiatives are top-down, too broadly defined, with vague objectives, insufficient resources, and limited industry leadership. The results are predictably disappointing and typical of what has happened in Wisconsin. Our strategy is to focus state resources on industry-led efforts that have the opportunity to create 25,000 jobs or more and where the injection of WEDC-led efforts will make a difference. Rather than a generic ‘industry cluster’strategy, we will mobilize resources and provide custom solutions to advance select business consortia opportunities. The result will be significant job growth and advancement of key Wisconsin industries.

(Wisconsin Department of Commerce, 2011)

Clearly the lack of a comprehensive economic development plan and the fragmentation of economic development efforts are major issues.

Similar tendencies have been visible in the Danish case, regardless the fact that the cluster strategies tried to take advantage of existing bottom-up processes by focusing on potential and emerging clusters (Cornett and Ingstrup, 2010). The regional cluster policy in Southern Denmark, integrated in a broader regional development programme, is rather young and large amounts of funding and political prestige have been invested. However, to a certain extent it has been local or sectoral initiatives, such as the Sønderborg examples, that have transformed the strategy into practice. At least, compared to most other Danish regions, the programme is relatively explicit with regard to purpose and targets (Cornett, 2008: 229–32).

Conversely, economic development efforts at the local level, however, have been highly successful. At the city level, the most effective tools in economic development in the last twenty years have been TIFs (Tax Incremental Funds) and SPEC (speculative) buildings. TIFs have been used to build industrial parks and to develop blighted blocks in the downtown area. In the case of TIFs, the city issues bonds that are used to pay for infrastructure improvements to attract businesses, whose taxes are in turn used to pay back those bonds. As for SPEC buildings, which are built in the expectation of being occupied by businesses looking for immediate occupation, four of the five buildings built by the city were eventually bought by their temporary tenant businesses and one is currently leased.

Also the Danish local (municipality based) initiatives have positive results, in particular with regard to fostering ‘triple helix’type relations between knowledge institutions, the public authorities and companies. In both cases, the impact has to be found in individual partnerships rather than in statistically significant creation of employment or additional economic growth on the regional macro level. Furthermore, both the Eau Claire and Sønderborg based cluster initiatives are anchored in ‘triple helix’types of relations, and policies aiming at creating regional innovation systems in particular fields and initiating the dissemination of knowledge. In Denmark as well as in Wisconsin, the regional development policies have tried to identify existing and emerging clusters as points of departure for cluster-based development initiatives. In both areas existing industries or branches are important anchors for development initiatives within or outside the formal cluster initiatives.

One significant difference appears to be the level of commitment to a cluster development policy in both regions (Southern Denmark and West Central Wisconsin). In Denmark, this approach has brought together more entities, resulting in a more comprehensive and better funded policy effort. In Wisconsin, the cluster policy to economic development is very recent and has been poorly structured, being highly sensitive to political changes. Moreover, there is little coordination among regions within the state and no cooperation among the states of the type of border triangle cooperation effort, even though the local economies are well integrated with neighbouring states, such as Minnesota and Illinois.

Recently, public sector employment has been affected by tighter budgets. In this regard, the two invested regions in Denmark and the US have been similarly affected by the recent developments.

Concluding remarks and perspectives

The aim of this chapter was to shed some light on the regional and local application of cluster oriented local development initiatives, and under which conditions a cluster-based development policy seems to be a realistic and fruitful policy option. Based on a case study of two medium sized city regions and their cluster initiatives, the local implementation and instruments have been discussed. In both cases the results are rather mixed. Both areas have taken their point of departure in existing relative industrial strongholds and set up a triple helix type of cluster facilitating policy, where the local university and knowledge institutions are important assets. In particular, instruments targeted at the improvement of innovation capabilities are important.

The chapter is not assessing the general potential of cluster stimulating policies, but at least we can conclude that the macro level impact of the implementation of cluster promoting strategies in two non-metropolitan regions, with limited general endogenous potentials compared to centre regions, is hard to identify. Interviews indicate that in specific cases the picture may differ, and that initiatives can be fruitful. Further analysis is needed, in particular on the impact of clusters on economic growth.

However, the crucial issue in both regions is the limited potential of a policy primarily addressing the long term change of the local economic base to cope with the short term employment and income decline caused by the economic cycles (i.e. the financial crisis). Furthermore, the overall alteration of the international production system away from low-skill physical production in the mature western economies reinforces the structural problems.

Nevertheless, the comparative assessment of local business development in two medium sized regions in different economic systems – Sønderborg in the southern part of Denmark and the Eau Claire area in Western Wisconsin – shows interesting similarities. First, cluster initiatives have been very popular on the policy level, but the practical and financial support has been more limited in both cases. Second, both examples prove that in practice the policy instruments have to be used with the point of departure in the existing economic base, which makes the instruments less feasible to cope with fundamental changes in the local economy in short and medium term perspectives. It is also common to use a ‘triple helix’set-up to include the local knowledge institutions to improve the knowledge base in business and industry. A problem in that regard is that the local universities and other knowledge institutions in both regions do not provide overall academic and technological coverage of the relevant fields.

Overall, the differences in the institutional framework in the United States may pose additional challenges because of greater fragmentation and the need to reconcile policies and programmes set by multilevel organizations (federal, state, regional, county and city) compared to Denmark, even if the EU level is included in the framework.

In general, case study-based investigations can only shed some light on the merits of a cluster-based regional development policy in a specific institutional context and local economy. Systematic studies of the optimal institutional set-up in specific national or regional economic systems, as well as empirical data-based assessment of the economic impacts on growth and employment, are needed.

Notes

1 Acknowledgement for the special session ‘Cluster Development and Regional Transformation in an Economic Perspective’at the 14th Uddevalla Symposium, 16–18 June 2011 in Bergamo, Italy.

2 For an overview of cluster formation in a ‘bottom-up’perspective see Atherton and Johnston (2008).

3 Based on a survey of cluster and network literature, Pickernell et al. (2007) identified eight types of cluster frameworks. The eight types include: industrial complex, hub and spoke, Italianate district, Marshallian, urban hierarchy, social network, virtual organization and satellite industrial platform. In particular, the last two seem to be relevant in policies aimed at linking regional clusters to global systems of production. For a brief summary of the eight types, see Table 1 on page 343 in Pickernell et al. (2007).

4 See also Pickernell et al., 2007.

5 In a policy context, these types of measures are supply-side oriented, which implies that the focus is mainly on the input side rather than on the outcome, i.e. economic growth and employment.

6 On 8 February 2010, the first-ever White House-led inter-agency taskforce on RICs published their Multiagency Funding Opportunity Announcement (FOA) of up to $129.7 million over five years, to support a regional innovation cluster that will develop and commercialize new building efficiency technologies for national and international distribution.

7 See Humphrey School of Public Affairs (2009) for a list of cluster studies in the United States.

8 The Wisconsin Technology Council is the science and technology advisor to the governor and the legislature. Four University of Wisconsin sponsored ‘economic summits’from 2000 to 2003 produced two reports that mapped where the state's economy should go and how to get there. A cluster-based approach to economic development was part of that vision, and a series of key recommendations were offered to that effect; http://www.wisconsin.edu/summit/archive/2000/papers/.

9 Xcel Energy has regulated operations in eight Western and Midwestern states, and revenue of more than $9 billion annually. They own more than 35,000 miles of natural gas pipelines. It is also the number one wind power provider in the nation and is ranked number five for solar power capacity. They engage in significant economic development efforts and community activities through the Xcel Energy Foundation.

10 Because of the regional and municipality reform in Denmark, fully comparable data are not available. However, for the period until 2006, the figures for the County of Sønderjylland and Sønderborg are: Total: 97/100 agriculture, fishing, mining, etc.; 76/72 manufacturing; 85/94 electricity, gas and water supply; 76/64 construction; 108/104 trade, hotels, etc. 95/103. Transport: 84/88, Mail, Financial services etc.: 96/92, Business activities: 185/158, Public service: 103/100 Associations, culture and refuse disposal activity not stated elsewhere: 98 /100 (Source: Danmarks Statistik Statistikbanken 2011).

References

Atherton, A. and Johnston, A. (2008), ‘Cluster Formation From The “Bottom-Up”: A Process Perspective’, in C. Karlsson (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Cluster Theory, Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar: 93–113.

Audretsch, D. B. (2006), ‘The Knowledge Spillover Theory of Entrepreneurship and Spatial Cluster’, in I. Johansson (Ed.), Innovations and Entrepreneurship in Functional Regions, Trollhättan, Sweden: University West: 177–88.

Cornett, A. P. (2008), ‘Cluster Development Policy as a Tool in Regional Development and Competitiveness Policy: Theoretical Concepts and Empirical Evidence’, in I. Bernhard (Ed.), Spatial Dispersed Production and Network Governance, Trollhättan, Sweden: University West: 221–36.

Cornett, A. P. and Ingstrup, M. B. (2010), ‘Cluster Development as an Instrument of Regional Business Development Policy: Concepts and Danish Reality’, in K. Brown, J. Burgess, M. Festing and S. Royer (Eds), Value Adding Webs and Clusters: Concepts and Cases, München, Mering, Germany: Rainer Hampp Verlag: 43–61.

Danmarks Statistik (2011), ‘Statistikbanken’. Available at: http://www.statistikbanken.dk (accessed 12 April 2012).

Danske Regioner and Kommunernes Landsforening (2007), ‘Regional vækst og udvikling – et fælles ansvar: Samarbejde om vækstfora, væksthuse og regionale udviklingsplaner’. Available at: http://www.regioner.dk/Publikationer/Regional+udvikling/~/media/ migration%20folder/upload/publikationer/regional%20udvikling/vaekstforaregudvikl-ing2007.pdf.ashx (accessed 27 August 2012).

Deller, S. (2010), ‘Location-Quotients and TRED’. Available at: http://nercrd/psu.edu/ TRED/index.html (accessed 20 April 2010).

Drejer, I., Kristensen, F. S., and Laursen, K. (1999), ‘Cluster Studies as a Basis for Industrial Policy: The Case of Denmark’, Industry and Innovation, 6 (2): 171–90.

Engelstoft, S., Jensen-Butler, C., Smith, I., and Winther, L. (2006), ‘Industrial Clusters in Denmark: Theory and Empirical Evidence’, Papers in Regional Science, 85 (1): 73–97.

Etzkowitz, H. and Leydesdorff, L. (2000), ‘The Dynamics of Innovation: From National Systems and “Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of University-Industry-Government Relations’, Research Policy, 29 (2): 109–23.

Forward Wisconsin (2011), ‘Pewaukee, Wisconsin. Industry Clusters’, Available at: http://www.forwardwi.com/category44/Industry-Clusters (accessed 20 April 2011).

Gordon I. R. and McCann, P. (2000), ‘Industrial Clusters: Complexes, Agglomeration and/or Social Networks?’, Urban Studies, 37 (3): 513–32.

Hefty, T. and Torinus, Jr., J. (2009), ‘Wisconsin Flunks its Economic Test’, Wisconsin Interest, 18 (2). Available at: http://www.wpri.org/WIInterest/Vol18No2/Hefty-Torinus18.2.html (accessed 24 April 2011).

Humphrey School of Public Affairs (2009), ‘Industry Cluster Studies’. Available at: http://www.hhh.umn.edu/centers/slp/economic_development/industry_cluster_studies.html (accessed 24 April 2011).

Ingstrup, M. B., Sørensen, J., Sønderskov, O. and Thybo, M. (2009), ‘Klyngestrategier i Region Midtjylland og Region Syddanmark’, in P. V. Freytag, K. B. Munksgaard and K. W. Jensen (Eds), CESFO Årsrapport 2009, Kolding, Denmark: Syddansk Universitet: 7–10.

Karlsson, C. (2008), ‘Introduction’, in C. Karlsson (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Cluster Theory, Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar: 1–19.

Karlsson, C., Johansson, B. and Stough, R. R. (2005), ‘Industrial Clusters and Inter-Firm Networks: An Introduction’, in C. Karlsson, B. Johansson and R. R. Stough (Eds), Industrial Clusters and Inter-Firm Networks, Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar: 1–25.

McCann, P. (2008), ‘Agglomeration Economics’, in C. Karlsson (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Cluster Theory, Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar: 23–38.

Martens, H. (2008), ‘Lokal Erhvervsudvikling i Ny Sønderborg kommune’. Available at: http://static.sdu.dk/mediafiles//Files/Om_SDU/Institutter/Ier/CESFO/NS%20RSA/Konference%20april%2008/H%20Martens%20DK%20NSRSA%202008.pdf (accessed 27 August 2012).

National Governors Association (2002), ‘A Governor's Guide to Cluster-Based Economic Development’. Available at: http://www.nga.org/files/live/sites/NGA/files/pdf/AM02CLUSTER.pdf (first accessed 24 April 2011).

Pickernell, D., Rowe, P. A., Christie, M. J., and Brooksbank, D. (2007), ‘Developing a Framework for Network and Cluster Identification for Use in Economic Development Policy-Making’, Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 19 (4): 339–58.

Porter, M. E. (1990), The Competitive Advantage of Nations, New York: Free Press.

Porter, M. E. (2003), ‘The Economic Performance of Regions’, Regional Studies, 37(6 and 7): 549–78.

Region Sønderjylland-Schleswig (2011), ‘Syddanmark Pendlerinfo’. Available at: http://www.pendlerinfo.org/wm301579 (accessed 29 April 2012).

Syddansk Vækstforum (2009), Sammenhæng og fokusering, Vejle, Denmark: Syddansk Vækstforums Årsrapport.

US Bureau of Labor Statistics (2010), ‘Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) Location Quotient Calculator’. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/data/ (accessed 20 April 2011).

US Department of Commerce, Economic Development Administration (2011), ‘Annual Report to Congress’. Available at: http://www.eda.gov/pdf/FY2011_EDA_Annual_Report.pdf (accessed 24 April 2011).

West Central Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission (2009), ‘West Central Wisconsin State of the Region Working Paper: Economic Development’, April 2009. Available at: http://wcwrpc.org/Regional_Comp_Plan/6_Working_Paper_Econ_Dev.pdf (accessed 24 April 2011).

Wisconsin Department of Commerce (2003), ‘Fostering Cluster Development in Wisconsin’. Available at: http://www.cityoflacrosse.org/DocumentView.aspx?DID=2126 (accessed 24 April 2011).

Wisconsin Department of Commerce (2011), ‘WEDC Strategic Plan Draft’, 23 March 2011. Wisconsin Paper Council (2003), ‘The State of Wisconsin's Paper Industry’. Available at: http://www.wipapercouncil.org/documents/StateReport.pdf (accessed 24 April 2011).

Wisconsin Technology Council (2002), ‘Vision 2020: A Model Wisconsin Economy’. Available at: http://wisconsintechnologycouncil.com/uploads/documents/Vision_2020_web2.pdf (accessed 24 April 2011).