5 Natural heritage, mass tourism

Conservation networks and coastal land use conflicts

In the span of a few decades, Egypt’s coasts have been transformed. Strings of holiday villages, secondary luxury homes, and resorts—many left half-constructed by absentee investors—cover vast swaths of coastline, from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea. The coasts of the Red Sea and Sinai Peninsula host some of the most spectacular coral reef systems in the world, as well as stunning desert landscapes and rich historical–cultural attractions. These attributes, combined with extensive state incentives for land development, produced a boom in coastal tourism during the 1990s and 2000s. By 2002, the Red Sea and South Sinai governorates accounted for approximately half of all tourism receipts to Egypt, and half of all tourist arrivals in the country (Meade and Shaalan, 2002: 3–4). Most of these tourists came for sun, diving, and snorkeling, instead of the country’s traditional tourism brand of antiquities. Rather than traveling down the Nile Valley from Cairo to Aswan and Abu Simbel, tourists increasingly flew directly from Europe, Russia, or Cairo to small airports along the coasts, including those in the towns of Hurghada, Sharm el-Sheikh, Marsa ‘Alam, and Taba.

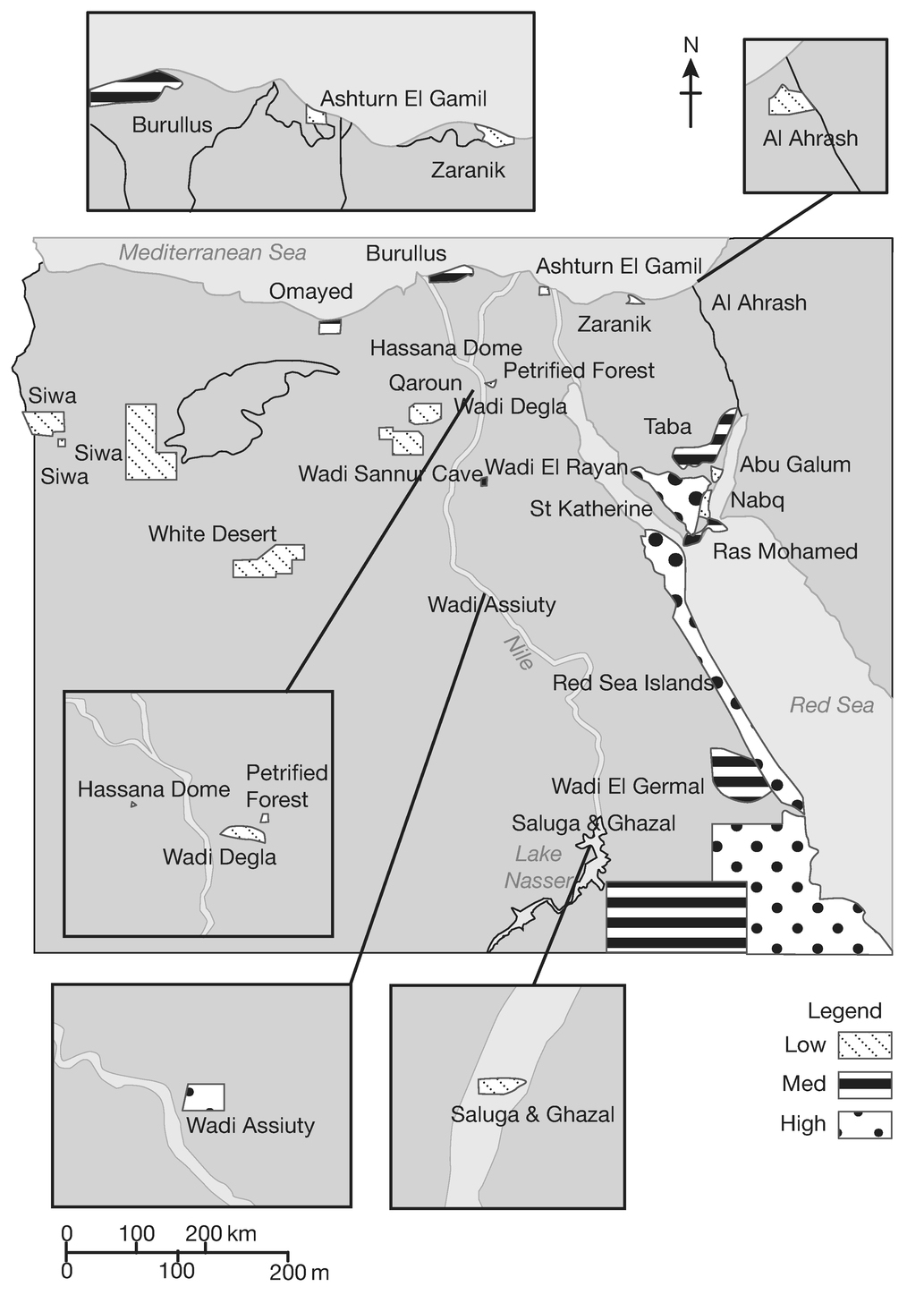

Not surprisingly, the building out of Egypt’s shorelines severely impacted coastal ecologies. As Egypt’s First National Report to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity noted in 1997, “The loss of coastal habitats should perhaps be Egypt’s primary conservation concern” (National Biodiversity Unit, 1997: 27). Beginning in the early 1980s, conservation experts had sought to build a network of protected areas in Egypt, particularly in coastal areas. These experts viewed protected areas as the most practical way to conserve biodiversity in the face of rapid real estate and tourism development. A small in-country network of local and resident expatriate experts provided continuity in personnel and institutional memory through a series of donor-funded projects to build a protected area network. They served as project managers, consultants, and field scientists for the Nature Conservation Sector of the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency. The continued engagement of network participants helped ensure that the many “outputs” of these projects—reports, studies, ecological surveys, business plans, integrated management plans, tourism assessments, maps, and databases—informed a consistent vision for the evolution of Egypt’s protected areas.

The results were, in many ways, impressive. Between 1982 and 2001, Egypt promulgated laws designating twenty-seven protected areas, covering 15 percent of the country. From 1991 to 2008, Egypt’s protected areas expanded by more than 2.3 million hectares (Global Environmental Facility Evaluation Office, 2009: 55). However, areas critical to preserving biodiversity—coastal zones, estuaries, mountain ranges, bays, and lagoons—were often the same places that generated significant profits from tourism, fisheries, land reclamation, and conversion to urban uses. With the expansion of acreage under protected area status, the conservation network encountered an increasing number of conflicting economic interests and land uses. These included influential investors closely tied to the Mubarak regime; the military sector, accustomed to free rein in remote frontier areas; centrally appointed governors with executive authority over land use; and local communities seeking access to resources. Even in seemingly remote desert interiors, protected area managers encountered actors involved in mining, quarrying, infrastructure development, military installations and exercises, and energy extraction.

This chapter analyzes how a managerial conservation network sought to engage these actors by building discursive, legal, and infrastructural forms of authority. Conservation experts framed habitat protection not only in terms of conserving biodiversity but also in terms of contributions to the national economy and national security. Protected area managers sought to build linkages to tourism investors by providing environmental assessments and recommendations. They further filed court cases to sanction violators. As importantly, protected area managers sought to build infrastructural authority directly within and around protected areas, seeking cooperative relations with local Bedouin tribes and channeling central resources to hiring rangers to monitor protected areas. At the national level, the relatively small managerial network repeatedly proposed creating a financially and legally autonomous protected area authority distinct from jurisdiction of the national environmental agency.

The politics of conservation in Egypt has involved more players over time as the tourism sector has expanded and conflict over the rents generated from land and marine resources has intensified. The last sections of this chapter analyze the advent of activist networks into conservation activities. These include diving and tourism operators with an interest in safeguarding their livelihoods through improved reef conservation, and advocacy organizations seeking to use the strong legal framework for protected areas to address land use conflicts in more populated rural and urban areas.

Establishing early protected areas in Sinai

Egypt’s first protected areas were established in the Sinai Peninsula in 1983 following Israel’s withdrawal, as stipulated by the Camp David Accords signed between Egypt and Israel.1 Wars between Israel and Egypt, and Israeli occupation after 1967, had kept Sinai in a state of political and economic uncertainty, preventing large-scale tourism investment. Under Israeli rule, resort development of the ‘Aqaba coast began in Na‘ma Bay, near Sharm el-Sheikh, and several other small towns, notably Nuweiba and Dahab. Between 1967 and 1981, Israel also zoned protected areas in parts of the ‘Aqaba and Suez coasts, the Straits of Tiran, the southern mountains around St. Catherine’s monastery, part of the northern Sinai coast, and parts of Lake Bardawil in the north.

With Israel’s withdrawal, Egyptian government ministries and international donors lost little time in preparing ambitious development and settlement plans for Sinai. With funding from USAID, the US consulting firm Dames and Moore prepared a seven-volume investment plan for Sinai. The plan emphasized mineral extraction, land reclamation, and industry for northern Sinai, while for the southern region, oil on the Gulf of Suez, fisheries, and tourism figured prominently. The Egyptian government’s 1987 five-year plan thus allocated 81 percent of planned expenditures in Sinai for loans for new settlements and for the building of basic infrastructure, including roads and utilities (Academy of Scientific Research and Technology, 1986: 1).

The Egyptian government viewed tourism development in Sinai through the prism of money and security. Tourism has long been a pillar of Egypt’s economy, generating foreign currency reserves and employment for large numbers of Egyptians. Tourism receipts remain the largest source of foreign exchange, helping the government balance its otherwise chronic imbalances in the current and trade accounts (Richter and Christian, 2007). Yet the tourism sector is also notably volatile, with tourist arrivals fluctuating in light of regional wars, terrorist attacks, and global economic downturns. Egyptian tourism receipts plummeted after the Gulf war in 1990–1 and attacks by Islamist militants in November 1992. Further militant attacks in 1997—in front of Cairo’s Egyptian Museum and near the Valley of the Kings at Luxor, where sixty-two people (mainly tourists) were massacred—only deepened the government’s commitment to reduce disruptions in foreign exchange receipts by diversifying tourism offerings out of the Nile Valley.

The Ministry of Tourism thus sought to promote “non-traditional” tourism (siyaha ghayr taqlidiyya) and “recreational” tourism (siyaha riyadiyya) on Egypt’s Sinai and Red Sea coasts, far from militant activities and urban conglomerations (Awad, 1998: 22). The government and international tourism operators increasingly marketed coastal tourism separately from the traditional antiquities-based Egyptian tourism. Promotional materials produced by the Ministry of Tourism emphasized not simply sun and sand, but safaris, windsurfing, and diving, reflecting worldwide trends toward adventure and recreational tourism.

In addition to diversifying tourism options, the government specifically wanted to increase the number of people living in Sinai, to settle the area as a buffer zone with Israel. Tourism was seen as a labor-intensive sector that could attract people from the Nile Valley. As a top official at the Tourist Development Authority observed to the author in 1999, “We were trying to find an activity to get people to move. We want to inhabit Sinai, for keeping it vacant makes it another arena for war.”2

Discursive authority: preserving biodiversity, attracting tourists

In light of these pressures for development, local conservation scientists and international organizations began to organize to protect the coral reefs of the Gulf of ‘Aqaba and the religious and archeological sites in the southern interior mountains. The monastery of St. Catherine and Gabal Musa (Mount Sinai), where Moses reportedly received the Ten Commandments, were a well-established basis on which to argue for historical preservation measures. Yet it was the ecological attributes of South Sinai that attracted a range of international advocacy groups working on migratory birds and wetlands preservation, coral reefs and marine habitats, and endangered wildlife and desert ecologies.

Conservation advocates were particularly concerned about safeguarding biodiversity in the Gulf of ‘Aqaba and Red Sea coral reefs. The first marine research center in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean was established on Egypt’s Red Sea coast at Hurghada in 1931, followed by the Heinz Steinitz Marine Laboratory in Eilat. In addition to producing numerous scientific studies detailing the marine life and ecosystems of the areas, internationally recognized marine scientists popularized the unique ecologies of the area through such venues as National Geographic (e.g. Arden, 1982). One such account was by the world-renowned shark expert Eugenie Clark. Clark worked with the US Fish and Wildlife Service in the Red Sea area and had studied as a graduate student in the Hurghada marine station. She later founded the Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota, Florida. For the readers of National Geographic, she depicted the Red Sea as “a world apart—geographically and ecologically,” as it had the highest salinity of any sea and harbored volcanic hotspots. This confluence of geologic and climatic factors produced the northernmost reef systems in the world, a rich “incubator” for a multitude of species, 15 percent of which were estimated to be found nowhere else (Clark, 1975: 341).

Much as Darwin’s account of the Galapagos Islands popularized the place itself as much as his understanding of it, these accounts created another mystique of place. This mystique no longer had its roots in Sinai’s religious or archeological heritage but in the newly emerging global understandings of biodiversity and ecological interrelationships. By 1982, an informal coalition of international environmental organizations interested in Sinai’s natural heritage included Friends of the Earth, the World Wildlife Fund, the Near East Division of the State Department, the Smithsonian Institution, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the Holy Land Conservation Fund, the Sierra Club, and the National Wildlife Refuge Association. In Great Britain, several voluntary associations—including Birds of Egypt, Friends of the Red Sea, and the Sinai Conservation Group—sponsored additional field surveys on migratory wildlife and reef ecology. Societies focusing on bird migration, such as the International Council for Bird Preservation and the Ornithological Society of the Middle East (both British groups), compiled lists of rare and endangered birds and their migration patterns (Holy Land Conservation Fund, 1989). Belatedly, the Egyptian government also announced the formation of the Association for the Protection of Sinai, a government-sponsored association headed by the then-Minister of Agriculture, Sayyid Mar‘i, which played little practical role in promoting conservation.

Prominent Egyptian conservation scientists, such as the botanist Mohamed Kassas, were acutely aware of the national security and economic imperatives driving the Egyptian government’s plans to develop Sinai. He and other Egyptian scientists focused their efforts on coordinating with international conservation networks to bring outside pressures on the political leadership. During his tenure as the head of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the IUCN Annual Congress adopted a general resolution that called on member commissions to provide financial and technical assistance to Egypt to conserve designated areas of Sinai. “This was ironic,” he later noted, “because at the time, in 1981, we had no protected areas. We had only laws under the Ministry of Agriculture protecting some specific species.”3

Discursively, Egypt’s conservation experts worked to make international concerns viable domestic policy choices by emphasizing the developmental benefits of protected areas. Reports by Egypt’s scientific and educational institutes argued that protected areas should “realize national goals…considering a core goal in the process [is] attracting settlements” (Academy of Scientific Research and Technology, 1986: 1). Conservation scientists thus proposed that different kinds of natural reserves, with different levels of protection, be established. Drawing upon a variety of park models employed throughout the world, the 1981 report called for establishing “natural parks” (mutanazzahat tabi‘iyya) open to tourism, as well as “natural protectorates” that would be closed to tourism but open for scientific study. Although the tourism park model was predominant in the United States and Africa, the authors noted that the scientific preserve was used extensively in Western Europe (National Committee to Preserve Nature and Natural Resources, 1981: 7). By shielding protected areas from development, conservation scientists hoped that protected areas would safeguard the country’s “natural inheritance” (ta’min al-wiratha, discussed in Chapter 2) at the same time that they served as tourist attractions. Protected areas would also sustain critical natural resources and food production, such as fisheries (Academy of Scientific Research and Technology, undated).

A National Committee to Preserve Nature and Natural Resources was convened in 1981 and charged with drafting a national action plan for a network of protected areas (National Committee to Preserve Nature and Natural Resources, 1981). The committee provided an extensive list of potential protectorates in addition to those proposed in Sinai, listing the Gabal ‘Elba region on the southeastern border with Sudan; the Red Sea mountains; Red Sea coastal areas with coral reefs; the northern Delta lakes; the arid Gilf Kabir plateau in the southwest; parts of the manmade Lake Nasser; parts of the Mediterranean coast; an oasis in the Western Desert; and a wadi in the Eastern Desert (ibid.: 9). This blueprint for establishing a formal network of protected areas changed remarkably little in the two decades following its circulation, except for the addition of small, compact sites near urban areas and Nile islands threatened by tourism development.

Existing Israeli-designated protected areas in Sinai made the Egyptian regime particularly sensitive to scientific and international criticism about the environmental costs of future development in Sinai. In citing legal and organizational precedents for establishing Egyptian protected areas, Egyptian scientists did not focus on existing Israeli protectorates but instead cited as precedents domestic initiatives regarding nature conservation. These included a 1980 directive issued by President Anwar al-Sadat on nature protection, Egypt’s signing of the International Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, and a number of research reports on conservation carried out by specialized national committees (ibid.: 8).

Conservation scientists also enlisted prominent international scientists and personalities to make direct personal appeals to the then-President Sadat. Eugenie Clark was asked to petition President Sadat to declare Ras Mohamed, at the southern tip of Sinai, Egypt’s first national park, which she did.4 Similarly, in 1984, Kassas enlisted Britain’s Prince Philip, in his capacity as president of the World Wildlife Fund, to ask President Sadat to declare Gabal ‘Elba on the Red Sea Coast a protected area. The Gabal ‘Elba petition itself was the culmination of earlier work done by a range of international, Egyptian, and Sudanese scientific teams under the sponsorship of the World Wildlife Fund. Consonant with conservation scientists’ efforts to market the tourism potential of protected areas, the Gabal ‘Elba petition noted that the area adjacent to the proposed protected area was “especially timely for tourist development in view of the completion of the new coastal highway by the Red Sea” (Kassas, 1984).

By the 1990s, conservation scientists began to frame the need for protected areas in terms of conserving natural “heritage” (turath). Egypt’s first National Report to the Convention on Biodiversity in 1997 explicitly sought to redefine the notion of “heritage” to include natural resources:

Egypt is endowed with a rich natural heritage as valuable as its cultural heritage; ranging from breathtaking desert landscapes, colorful coral reefs, spectacular untouched wilderness, pristine coasts, a rich and fascinating wildlife, unique geologic formations, and a high diversity of biological components and ecosystems. However, given the current rapid rate of development in Egypt, many unique ecosystems, landforms, biological components, and other natural heritage resources, are swiftly being lost and irreparably degraded… This waste of the country’s irreplaceable natural heritage is often unjustifiable, occurring mainly due to ignorance, severe undervaluing of these resources, and limited enforcement of measures to control and monitor development activities.

Egypt’s 1998 Biodiversity Action Plan and the 2001 National Environmental Action Plan further positioned protected areas as the principal mechanism for conserving natural heritage and biodiversity in the country (Ministry of State for Environmental Affairs, 2001b; National Biodiversity Unit and EEAA, 1998). Through field surveys and taxonomy studies, Egypt’s conservation experts refined their claims about where this natural heritage was most concentrated and how protected areas would contribute to maintaining species and ecosystems (Kassas, 1995; Baha El Din, 2006). As these scientists noted, many indigenous flora and fauna had largely disappeared or were threatened with extinction. Egypt’s remaining biodiversity was found in relatively few locations, making habitat conservation critical.

Building infrastructural authority in the South Sinai protected areas

By the early 1980s, the efforts of international environmental advocacy networks and local scientists resulted in the passage of Law 102 (1983), which demarcated several areas in South Sinai as Egypt’s first protected areas. As discussed in Chapter 2, the law was exceptional in that it vested executive authority for implementation and oversight of these areas to the Nature Conservation Sector within the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA), although the agency as a whole was only authorized to coordinate between existing government ministries. Law 102 also provided a long-term funding mechanism, through the creation of an Environmental Fund to collect park entrance fees and levy fines for violations, such as damaging coral reefs and oil spills. The executive regulations specified that the EEAA would have control over this fund, and that part of the proceeds would go towards improving the reserves and providing compensation for whistleblowers as necessary. Law 102 further gave the Nature Conservation Sector (NCS) authority not only over protected areas, but also over coastal setback areas, in practice considerably expanding its spatial jurisdiction.

Multilateral and bilateral donors played a significant role in helping to transform selected protected areas from legally designated “paper parks” without infrastructural authority into parks with an institutional presence on the ground. The EU supported institution-building at the first national parks in South Sinai, while the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) worked along Egypt’s Red Sea coast, and the Italian cooperation agency focused on protected areas in the Fayoum oasis near Cairo. By the 2000s, the World Bank’s Global Environmental Facility channeled funds through the UNDP to establish management plans for the wetland protectorates of the northern Mediterranean coast and to help establish a more autonomous, capable conservation sector at the national environmental agency.

EU-funded projects for the South Sinai protected areas began in 1989. Focused initially on Ras Mohamed National Marine Park, these projects soon expanded to cover the St. Catherine, Nabq, and Taba protected areas in southern and central Sinai. The EU recruited expatriate managers with significant experience managing protected areas in the Middle East and Africa. Several of these individuals became an integral part of Egyptian managerial conservation networks as they stayed in the country to work on a series of donor-funded conservation projects. For example, the program manager for the Gulf of ‘Aqaba protectorates, Michael Pearson, lived in Egypt for over a decade after a stint working on protected areas in Tanzania.5 The project manager for Ras Mohamed, Alaa D’Grissac, had previously worked in thirty-two countries on protected areas, and had prepared portions of the Mediterranean Action Program related to protected areas.6 John Grainger, the project manager for the St. Catherine protected area from 1996 to 2003, had previously worked in the development of protected areas in Saudi Arabia, Ghana, Sri Lanka, and Kuwait. After his work at St. Catherine, he worked as an adviser for the USAID-funded Wadi al-Gamal National Park on the southern Red Sea from 2003 to 2004, served as the IUCN team leader for the Nature Conservation Sector Capacity Building Project, and then worked as a freelance conservation consultant in Egypt from 2007 to 2010.7

These managers sought to create infrastructural authority for the Sinai parks by fostering cooperation with local stakeholders and building institutional capacities in the field. In contrast to the standard hiring practices within Egyptian government agencies, EU project managers directly controlled expenditures, allowing them to make their own decisions about staffing and operations. The Nature Conservation Sector and the EU projects in South Sinai obtained exemptions from public-sector hiring rules, which typically required government agencies to hire laid-off older public-sector workers, in order to hire young, well-trained, and committed graduates. In the late 1990s, EU-supported salaries for the protectorates division were competitive enough that several park rangers returned to employment in Egypt from the United States or Canada.8 These practices, however, persisted only as long as the external donor-funded projects lasted, creating significant challenges for retaining skilled employees once the projects ended.

The two most important governmental stakeholders for the emerging protected areas regime in South Sinai were the Egyptian military and the provincial governors appointed directly by the president. Although the Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt set limits on the numbers and kinds of military forces stationed in the peninsula, the military retained use rights to large tracts of land in Sinai, and internal security forces manned a number of checkpoints. Protected area managers also had to work closely with military appointees to the Nature Conservation Division at the environmental affairs agency. The Mubarak regime appointed a number of former military and internal security officials to top administrative positions at the Nature Conservation Sector as many protected areas were in strategically sensitive border zones near Sudan, Israel, and Libya. The first appointed CEO of the EEAA, Muhammad ‘Eid, was an ex-general from the army’s division of chemical warfare. He appointed another retired general, Ahmad Shahata, as the project liaison between the Nature Conservation Sector and the EEAA. He also appointed another former member of the division of chemical warfare as the Egyptian manager of Ras Mohamed National Park. This official was also the brother-in-law of the then-Minister of Defense, Muhammad Husayn Tantawi. Tantawi later served as the acting president of Egypt and head of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) in the wake of the January 2011 uprising.

Protected area managers referred to their interactions with military personnel and appointed governors as “educating the state.”9 Several military appointees became convinced of the importance of protected areas, and helped facilitate basic infrastructure and enforcement activities. In Ras Mohamed National Park, rangers and the coast guard conducted joint land and sea patrols in the early years after the park was founded. But this cooperation was contingent on recognizing the first claim of the military and security forces to land use and service provision. For instance, the military built the water supply lines in Ras Mohamed, under a service division charged with providing water and electric lines to rural areas.10

Working relationships between park managers, military appointees to the NCS and the EEAA, and the local military officials in South Sinai facilitated extensions in the boundaries of the South Sinai protected areas. Ras Mohamed National Park was expanded in 1989 and 1991 to include coastal zones up to the highest equinox tide line. In 1992, two “multiple-use” areas were designated on the Gulf of ‘Aqaba. With the creation of the St. Catherine’s Protected Area, which encompassed much of the interior southern mountains, over a third of the territory of the South Sinai governorate was under formal protected status. The entire system of offshore coastal reefs was declared protected when the 1994 Environmental Law required a review of any development less than 200 feet from the highest tide line.

As the protected area network expanded, provincial governors played an increasingly prominent role in facilitating or constraining the infrastructural authority of the South Sinai protectorates. Appointed directly by the regime in Cairo, provincial governors controlled the issuing of all sorts of permits and licenses. Cooperative relationships with the governor simplified implementation of protected area management schemes, while conflicted relations could stall everything from housing construction for rangers to obtaining land for solid waste sites. Protected area managers thus sought to educate successive governors about the economic value of protected areas through field visits, formal and informal presentations, and providing public services, such as supplying a health clinic for local residents.

Governors, however, were often more interested in the direct financial benefits of resource exploitation from quarries, mines, and real estate development than in conservation. As regime appointees, they wanted to demonstrate meeting central plans and targets. For instance, the South Sinai governor wrote directly to the Minister of State for the Environment in 1998 to argue that attempts by the protected area managers to control quarrying in the St. Catherine protectorate were hindering mineral exploitation, blocking development, limiting employment, and leading to the depopulation of Sinai in the name of nature conservation (Pearson, 1990: 3).

As the network of protected areas consolidated itself across the landscape of southern and central Sinai, park managers also began to establish initiatives with Bedouin tribes in and around the parks. This was in stark contrast to the customary treatment of locals by the central government. The regime in Cairo had excluded Bedouin tribes from any significant participation in both central and provincial administrations; development plans focused on attracting elite investors and migrants from the Nile Delta rather than promoting tribal interests (International Crisis Group, 2007). The central government also appointed tribal sheikhs as intermediaries, restricting the mantle of tribal leadership to those approved by the regime.11 Not surprisingly, therefore, field surveys conducted by the Nature Conservation Sector in 1996 found that “the relationship between Sinai Bedouin and Egyptian authorities is poor now, and communication is almost nonexistent” (Hobbs, 1996).

In contrast, the Nature Conservation Sector sought to build cooperative relationships with Bedouin tribes by providing employment and services, and by explicitly recognizing Bedouin land uses in protected areas. The two multiple-use areas of Nabq and Abu Ghalum recognized seasonal Bedouin settlements and traditional fishing areas, in contrast to the land use maps drawn up by the central ministries in Cairo. These multiple-use areas were also zoned to allowed limited tourism, while seeking to insulate the most sensitive ecosystems, such as mangroves, dune systems, and coral reefs, from development. In the Abu Ghalum protected area, for instance, about 20 percent of the area was zoned for tourism development, and traditional fishing was allowed along most of the offshore reef (Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency and the European Union, 1993).

In the St. Catherine protected area, an estimated 7,000 Bedouin lived in and around the park in 2006 (Nature Conservation Sector, 2006). The St. Catherine protectorate employed forty-eight Bedouin out of its sixty-six employees by 2002, including thirty community guards. The protected area project helped establish a handicraft collective, FanSina, owned by its 300 Bedouin women employees, and also supported a veterinary clinic, a mobile health clinic, and an eco-lodge owned by twenty-seven Bedouin families (ibid.: 41).

Rangers also received training on community-based management of protected areas. One ranger recalled that spending three months in South Africa’s Kruger National Park “changed my way of thinking about local communities. I learned how to talk with them and consult them.”12 While serving as the manager at the Taba protected area for seven years, he convened an informal steering committee of tribal leaders from local Bedouin tribes to provide input on park management decisions. Their input was influential in altering some park plans, such as the decision not to build a paved road to bring in more tourists by outside operators, but rather upgrade the existing camel path by which Bedouin transported tourists by jeep and camel. “We saved a lot of money on the road and we also helped the local community keep an important source of income,” observed the ranger.13

Liberalizing tourism and limiting conservation on Egypt's coastlines

Success in conserving portions of South Sinai through a network of protected areas was soon challenged by state promotion of coastal tourism development. State and donor interventions focused on liberalizing the tourism sector to encourage private investment in tourism services, infrastructure, and land development (Sakr et al., 2009: 29).

Following an institutional blueprint supplied by USAID and the World Bank, Presidential Decree No. 274 for 1991 established the Tourism Development Agency (TDA) as a legally autonomous “economic authority” authorized to distribute vast tracts of coastal land (Ministry of Tourism, undated). Using property maps drawn up by the Ministry of Defense and Military Production, the TDA was allocated most desert land outside of municipal boundaries, protected areas, and military zones for tourism investment.14 Under Egyptian law, all land not located within municipal boundaries or registered as private agricultural land is claimed as state property (malakiyya khassa lil-hukuma), and thus no legal provisions were made for customary and seasonal land uses.15

To encourage investment, land prices were set extremely low, ranging from US$1 per square meter along the Sinai coastline, whose offshore reefs are some of the most spectacular in the world, to US$10 per square meter near St. Catherine’s monastery and Mount Sinai (Sowers, 2003: 225). Land was similarly priced along the Red Sea coast. The TDA allocated land on the basis of a nominal application, to be followed within three years by unspecified substantive improvements to the site. Investors enjoyed payment schedules of ten years, and 10–25-year tax holidays.16

This system of land allocation promoted speculation in land and a shift in landholdings to large conglomerates. Cheap land costs combined with large minimum plot sizes encouraged large investors to buy extensively. Investors reported it was easier to pursue real estate development in Egypt than in the surrounding countries of Greece, Italy, and Turkey, because large land parcels were available and environmental restrictions were not enforced. In addition, the three-year deadline for making tangible investments in their parcel provided ample time for investors to make small changes while the price of land increased. An Egyptian consultant for the Ministry of Tourism told the author, “Investors who have money may just wait to develop the land they purchase, so that the price increases in the meantime. The smaller ones do the same, but use bank loans to tide them over.”17 As the IMF noted in a critical review of these policies, delayed investment requirements and tax holidays merely restricted general state revenues and increased the tax burden on medium and small-sized firms unable to join the land acquisition rush (Goldrup, 1998; International Monetary Fund, 1998).

Reportedly, the TDA' transferred a number of land parcels to ex-military and security officials as well as private investors, many of whom resold the land as prices escalated. In interviews, some businessmen were candid about their decision to diversify into tourism and land development. One, a well-known importer of Ford automobiles, observed, “We diversify to follow the profitable sectors. A few years ago this was land, bought from developers in Sharm el-Sheikh and the Red Sea. I own some, bought from a developer who owned huge tracts.”18

Large investors typically combined tourism resort construction with investments in luxury secondary housing. The demand for coastal vacation villas and secondary apartments on the coast stemmed from several factors, including the paucity of secure investment vehicles for Egyptians other than land as well as increasing demand from the upper classes for holiday locations far from the crowded beaches of traditional holiday destinations, such as Alexandria, ‘Agami, and Ma‘moura. Most resort complexes built on the Red Sea and Sinai coasts therefore mixed hotels and holiday villages with villas, apartments, and/or timeshare sales. Many of the investors working on the coastlines also developed dedicated luxury gated communities around Cairo, such as Muhammad Farid Khamis in al-Shorouq, the Tal‘at Mustafa Group in al-Rihab, and Ahmad Bahgat in Dreamland.

State policies and economic incentives thus combined to produce spectacular growth in Egyptian coastal tourism development during the 1990s and 2000s. Between 1993 and 2007, according to Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism, the number of tourist arrivals increased from 1.5 million to 11.1 million, tourism receipts rose in value from US$1.9 billion to US$9.5 billion, and lodging capacity grew from 27,300 rooms to 190,200 (Sakr et al., 2009: 4). Egypt’s coastlines along the Red Sea and the Sinai Peninsula accounted for the bulk of this investment.

The list of developers involved in coastal real estate included the wealthiest business conglomerates and investors in Egypt. One scientist who had worked extensively in coastal zone management for the Red Sea told the author in 1999 that:

Before, we used to say that the coastal tourism sector was the hajj [an older man] with the lukanda [small, non-luxury hotel] near the railway station, who then went to Hurghada (on the Red Sea) and built anything. But now it is only the tycoons.19

The “Charming Sharm Company,” for instance, was a consortium of twenty-eight investors including Muhammad Farid Khamis, owner of Oriental Weavers and former head of the Egyptian Businessmen’s Association. The consortium bought land in the Nabq protectorate development zone, ten kilometers north of Sharm el-Sheikh, for US$1 a square meter to be paid in ten-year installments with a three-year grace period on payments (Atraqchi, 1998).

El Gouna, a 9.93 million cubic meter parcel on the Red Sea developed and majority-owned by Orascom Development Holdings, contained fourteen hotels, two tourist villages, a golf course, several marinas, shopping malls, a vineyard, a bottling company, a brewery, and a hospital, in addition to 1,350 villas and 1,940 apartments (International Finance Corporation, 1997). For the Financial Times, El Gouna’s “pastel-painted domes and turrets beside a manmade lagoon” were “the brashest symbol of the Egyptian private sector’s relentless investment drive” (Huband, 1998). The International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private investment arm of the World Bank, invested not only in El Gouna, where it held a 5 percent stake, but also with the Farid Saad Group, developing the Red Sea resort of Abu Soma (Fiana and Partners, 1998: 224). Farid Saad was the former managing director of the Egyptian American Bank, as well as the import licensee for Nestle and Xerox in Egypt.

Not surprisingly, charges of corruption dogged investors and tourism officials long before the 2011 uprising brought formal charges against some of the most well-known figures in coastal real estate. Since the TDA wielded considerable discretionary powers to approve investment applications and collect revenues from land sales, top officials were frequently accused of wrongdoing. The first tourism minister to preside over the rapid allocation of coastal land, Fu’ad Sultan, resigned in 1994 over parliamentary allegations of corruption and favoritism. He later joined the board of directors of Orascom Development, one of the largest firms in Egypt and owned by the Suweiris family.

While elite business groups bought up land, local Bedouin communities were systematically excluded from the boom in coastal tourism. Beginning under the Israeli occupation of the Sinai Peninsula, Bedouin established small camps to service tourists, typically consisting of small huts, an open-air restaurant, a bathing area, and arrangements for diving trips and desert safaris. These operations, with low tourist densities and use of local materials, were local forms of ecotourism. As the real estate and tourism market saw an influx of Gulf and Egyptian investment along the Gulf of ‘Aqaba during the 1990s, however, bulldozers and truckloads of soldiers forcibly displaced a number of existing small Bedouin camps established to service tourists (Bortot, 1999).

Government agencies at all levels proved hostile to Bedouin land claims and few Bedouin successfully entered the expanding tourism sector. The only Bedouin to own a hotel and dive operation in Sharm el-Sheikh recalled the many difficulties he faced in an interview in 2011:

I acquired a fishing boat and a local fishing license near Sharm el Sheikh in 1981. The Egyptian navy soon caught me near Tiran Island with an American photographer and his Israeli assistant, and told me that I was not allowed to take tourists without a permit for tourism, even though we Bedouin had done this when the Israelis were in control of the area, and we know the Red Sea very well. I went to prison in al-Tor, paid a fine, and then was released. A court eventually found in my favor, but still I had stopped work for three months.

So then I tried to get a legal tourist boat—I called her Freedom I. I built the boat here myself. The Egyptian officials told me I could only get the boat license to be skipper in Suez. So I traveled to Suez, and then to Alexandria, but each time the authorities refused. I have a friend who works in Cairo for the Nile Water Police, so I also tried through the Water Police. Still no luck— the water police said I needed a LE6,000 radio before they would consider my application.

Eventually I built a jetty, working illegally, here on the coast. I eventually was able to buy this land and legalize my jetty by finding a person from the government side to go in with me. I paid for the whole parcel but he got to take half of the land. The cost was LE5 per meter.

My story is like thousands of other Bedouin. The Bedouin feel like rubbish; we are treated like garbage. The government always uses the excuse of “the bad Bedouin” to deny us access to land and work. What has been left for us?20

The Tourism Development Authority was no different than other Egyptian government authorities in their approach towards Bedouin land ownership in the tourism sector. In an ill-concealed attempt to justify displacement of local Bedouin from areas zoned for tourism, a glossy investor brochure produced by the TDA for the ‘Aqaba coastline noted that:

The Om Mreikha Center [for Bedouin] was established in order to overcome the growing trend of Bedouin squatting in beach areas close to the borders of the Nuweiba city. This trend is quite dangerous and the establishment of the center would halt it and provide for a safer and more environmentally healthy region.

(Tourism Development Authority, undated)

Social and environmental impacts of coastal tourism development

Rapid tourism development of Egypt’s coastlines produced a number of social and environmental impacts. In South Sinai, the pace of land development from private investors and corrupt state officials soon overwhelmed government planning functions. By the EEAA’s accounting, between 1982 and 1993 the general population increased by 66 percent in southern Sinai settlements (Gulf of ‘Aqaba Protectorates Development Programme, 1997). While the total population increased from 28,929 people to 54,495 inhabitants between 1986 and 1996, far short of the Ministry of Planning targets for permanent residents, the numbers of tourism rooms far exceeded those set by the same ministry (Cole and Al-Turki, 1998: 11). In 1993–4, the numbers of tourist rooms set for the Ministry of Planning until the year 2017 were already exceeded in Sharm el-Sheikh by 60 percent (European Union and EEAA, 1998). The response of the Ministry of Planning was simply to repeatedly revise the targets for numbers of tourist beds upwards. The governorate followed suit: in the tenure of one governor of South Sinai, tourist bed ceilings for municipal land were repeatedly increased with no assessments of the consequences for municipal infrastructure.21

The TDA primarily sold linear coastal parcels with little development in clusters or townships to use land behind the direct coast. These parcels neglected to preserve such critical features as wadi flood zones, coastal access for investors behind the shoreline, or access for the public. This pattern of land allocation also discouraged economies of scale in infrastructure and public services that could have been achieved by grouping smaller parcels together in clusters. The TDA’s marketing brochures for the northern ‘Aqaba coastline, which it depicted as a new “Egyptian Riviera,” exemplified the extensive, linear designs proposed for tourism resorts (Figure 5.1).

This “Egyptian Riviera” marketing campaign captured the dreams of tourism officials and the fears of conservation experts. Long denounced in planning circles as a model of overdevelopment, the French Riviera was hardly a model for conservation. The lack of awareness about the tourism potential of Egypt’s reefs, in particular, among the top officials at the Tourism Development Authority in the late 1990s was striking. In an interview with the author in 1999, the head of the TDA lamented, “Here in Egypt, the marine attractions are not polished, they are not prepared. We have no Sea World, no aquariums, no sea restaurants.”22 This vision of tourism minimized Sinai’s greatest tourism assets, namely ecosystems that in terms of diversity and beauty could not be matched by aquariums or constructed attractions. Most of the European tourists who made up over half of Red Sea and Sinai tourism in 1997 were attracted precisely to the rugged wilderness and stunning undersea vistas that neither the French Riviera nor Sea World provide. The TDA, however, continued to use the Riviera-themed marketing campaign to attract investors to the Red Sea coastline (Chemonics International, 2008: 5).

Figure 5.1 Tourism Development Authority plan for “the Egyptian Riviera,” northern Gulf of ‘Aqaba

Source: Tourism Development Authority, 1999, promotional brochure

The TDA thus made little attempt to diversify tourism offerings to include ecotourism or low-impact forms of nature-based tourism. The tycoons and international hotel management chains alike generally strove to replicate the aesthetic and level of amenities found in luxury beach tourism elsewhere. In contrast to ideals put forth under the rubric of “eco-tourism” or vernacular architecture movements, which celebrate the unique aesthetics and materials of a particular location and culture, luxury secondary homes and hotels promoted the homogeneity of their products regardless of the singular attributes of place. Sinai had its own models of ecotourism, in local Bedouin camps and in such innovative small resorts as Basata (simplicity in Arabic), that conserved water, separated and recycled wastes, and used local materials and vernacular designs in resort construction. The TDA showed no interest in replicating or scaling up these kinds of tourism facilities. According to the head of the TDA, the government considered ecotourism a market niche that would not bring in the desired mass numbers of tourists.23

The impact of rampant tourist development quickly became clear. A 1998 field survey of thirty-one hotels compiled by the Sinai protectorate staff to monitor resort development in Sharm el-Sheikh found that almost every resort engaged in construction and operating practices that damaged offshore reefs (South Sinai Sector Staff, 1998). In addition, increasing numbers of desalination plants providing water for towns and resorts pumped concentrated brine effluent over the reefs.

Tourist development brought influxes of employees, tourists, and laborers to the region, with consequent increased demand for natural resources and municipal services, but with no mechanism for extracting taxes from private investors. Local governments and the NCS had little leverage to compel investors and central government ministries, particularly the Ministry of Tourism, to address the environmental and social “externalities” produced by the proliferation of enclave luxury resorts. Like other municipal authorities in Egypt, the South Sinai governorate and city budgets were centrally allocated, with no local accounting mechanisms for costs of services and needs assessment.

Water supply provided a striking example. Scarce water resources had long been decried by the government as the limiting factor to population expansion in Sinai, yet the boom in tourism development was decoupled from considerations of freshwater supply. A pipeline under construction to carry Nile water to southern Sinai was projected to use only half of its capacity due to limited supplies of Nile water. Generally hotels and resorts erected their own electricity generators and desalination plants, precluding economies of scale in utilities. Existing water, sewer, and power supplies did not perform to original capacity or specifications. The municipal water distribution in Sharm el-Sheikh, for instance, had estimated losses of 40 percent, while a nearby desalination plant built during the Israeli occupation had a desalination capacity of 1,750 cubic meters per day but by 1998 was only producing 400 cubic meters per day (European Union and EEAA, 1998: Annex 7: 11). Municipal sewage oxidation ponds were badly damaged and barely functioned, releasing untreated effluent into the water table. Since existing water systems did not meet municipal demand, water was increasingly trucked into towns and cities.

As water was trucked in or desalinated for ordinary household use, luxury hotel development, including golf courses and multiple outdoor swimming pools, consumed far more water than municipal usages. The average freshwater pool in South Sinai, given evaporation rates, required 25,000 liters daily, which was equivalent to the daily consumption of fifty guests in a five-star hotel, or the daily requirements of 300–400 urban residents in Sinai (ibid.: 5).

Creating legal and infrastructural authority for protected areas in South Sinai

Drawing on their legal authority to review developments that impacted coastal setbacks, park managers asked tourism investors to submit environmental impact assessments (EIAs) and project designs in order to identify problems and recommend mitigation measures. Recalled one military appointee to the NCS, “Some of the EIAs submitted for the Red Sea projects were just one page, containing no useful information. So we went directly to investors or the TDA to discuss project plans.”24 During the late 1990s and 2000s, rangers thus found much of their time dedicated to monitoring development sites, trying to rectify or minimize mistakes already made by investors and construction companies.

The South Sinai protectorates operated under a political constraint to accept virtually all projects in some form; observed the program manager in 1998:

We never apply the law in its strict sense, because if we did, the government would call us anti-development and shoot us down. So we don’t reject a development, but we try to propose ways to mediate or prevent damage, and explain to investors why this is in their own best interest.25

Protected area managers offered investors input into the design of lagoons, marinas, construction works, setback use, and disposal methods and, in return, obtained information about investment projects otherwise unavailable to them.

This informal, personalized form of coordination was possible, however, only when the number of investors was small. The rapid growth in tourism investment overwhelmed the emerging institutional capacities of the protectorates to monitor coastal development. The TDA approved investment applications regardless of the status of environmental impact assessments, while the pace of construction soon strained the small numbers of protectorate staff qualified to monitor investor compliance. The TDA did not supply the protectorates with information on allocated properties nor did it inform developers of existing regulations (South Sinai Sector Staff, 1998). In addition, the authority allocated land deemed unsuitable for construction, located in flood areas, security zones, or within the coastal setback area, without seeking the required EEAA approval.26

As investment accelerated during the mid-1990s, protectorate managers shifted from personal negotiation with investors to litigation. Their aim was to call attention to indiscriminate land allocations and the increasing number of coastal violations. The EEAA prosecutor reported to the author in 1998 that he had filed over two hundred cases against investors on the Red Sea and ‘Aqaba coasts, but that without a system of civil liability in place prosecutions were difficult.27 The Egyptian legal system was perfectly capable of devising laws for environmental civil liability, as fines for reef damage had long been quantified and monetized.28 No such system of civil penalties, however, existed for violations by tourism investors, meaning that the prosecutor could only file criminal charges, a much higher threshold for legal action, and the charges could be dismissed through the personal intervention of the president, any minister, or the centrally appointed governors. The prosecutor further reported that he was under pressure from his superiors not to file cases involving elite investors.

Nevertheless, the environmental agency’s prosecutor was able to obtain convictions in several court cases against leading investors. In the case of the five-star Hilton Residence built in 1990 in Sharm el-Sheikh, the EEAA sued for illegal fill of the shoreline. The owner was eventually convicted, but assessed a mere LE1 fine and a one-year prison term, from which he was excused. Hussein Salem, one of the first business tycoons to be charged with corruption in the post-Mubarak era, claimed land inside a protected area in order to construct a presidential villa; the prosecutor’s cases went to the highest court to stop construction.29

Tourism and protected areas on the Red Sea

Along the Red Sea coast, developing legal and infrastructural authority for protected areas proved even more challenging than it had in the Sinai Peninsula. Whereas the protected areas regime began in Sinai prior to tourism development, along the Red Sea coast tourism development outpaced the development of protected areas management. The TDA was given jurisdiction to develop most of the Red Sea coastline, including a five-kilometer strip from the shoreline inland. In contrast to the Gulf of ‘Aqaba, where a significant proportion of the coastline was eventually designated as protected and the coastal protectorates were territorially compact, terrestrial protected areas in the Red Sea consisted of two huge remote and rugged southern areas, Wadi al-Gamal and Gabal ‘Elba, near the border with Sudan, as well as a number of offshore islands with fringing reefs. In these remote areas it proved much more difficult for the Nature Conservation Sector to establish an institutional presence on the ground, in part because the military viewed these areas through the prism of border security.

International donors, particularly USAID, funded several projects for environmental management on the Red Sea coast, beginning in 1998 and continuing throughout the 2000s. As in the EU South Sinai areas, Egyptian conservation experts staffed key positions in these projects, working with such well-known US firms as Chemonics International and Winrock International. USAID support was channeled in large part through the Egyptian Environmental Policy Project (1998–2004), in which a significant component was directed toward land use planning for the Red Sea, followed by the US$17 million LIFE Red Sea project (2005–8). In addition to direct budgetary support of the Red Sea protectorates, USAID projects sought to introduce what the agency termed “sustainable tourism development.” The USAID-funded “Red Sea Sustainable Tourism Initiative” published best practices guidelines for coastal resort development, supported the creation of investor associations, and sought to create an environmental unit within the TDA itself. These initiatives reflected USAID’s ongoing attempt to work with the “private sector” in the belief that, as one USAID project document noted, “the design and program of an individual property is a personal and private decision” (Tourism Development Authority and United States Agency for International Development, 1998: 7). This project orientation ran counter to attempts by protected area managers to more directly influence investor decision-making, as had been done in South Sinai.

Instead, USAID supported creating environmental tourism investor associations. Members of these associations, however, consisted almost exclusively of large investors. For example, the attendees at the 1998 founding meeting of the “Tourism Investors’ Association to Protect the Environment” (Jam‘iyyat Mustathmari al-Siyaha lil-Hifaz ‘ala al-Bi’a) included Orascom Development’s Samih Suweiris, the Minister of Tourism, the Minister of Environment, and the head of the Tourism Development Authority. The men convened under the banner that read, “Tourism is a friend of the environment” (al-siyaha sadiq al-Bi’a) (“The Ministers of Tourism and Environment…,” 1998). The meeting highlighted the use of best practices and environmentally friendly tourism. Yet none of the investors present had invested in an ecotourism development, at least by the standards laid out in USAID’s manual on ecolodges: low-density, unobtrusive designs, local aesthetics and materials, and limited impact on the surrounding environment.

Egyptian conservation experts knew that “the private sector,” as an entity, would not take the lead on developing environmentally sensitive coastal developments, any more than “the state” had done so. These undifferentiated categories were of little value, in any case, for untangling the skein of land acquisition deals that unfurled during the 2000s as the TDA rapidly allocated coastal property.

One of the primary goals of USAID’s Egyptian Environmental Policy project was thus the development of a comprehensive, binding land use plan for the Red Sea coast, to be officially agreed upon by the Ministry of Tourism, the Ministry of State for Environmental Affairs, and the Red Sea governorate. The land use plan was to secure designated protected areas and promote a diverse array of tourism offerings, including ecotourism. To encourage governmental authorities to participate, USAID offered lump-sum cash transfers (tranches) once the land use master plan was officially signed. The fate of this Red Sea master plan aptly illustrates the difficulties that managerial conservation networks faced in seeking to strengthen legal regimes for land use planning and conservation. Reflecting back on the master plan he had helped to devise, a leading Egyptian environmental consultant observed:

The ministers finally signed the agreement, but then the map simply disappeared. A new minister at the EEAA, a new Red Sea governor, and a new tourism minister were appointed, and they never even knew about the map. Everyone just pretended it didn’t exist. The biggest mistake was that USAID transferred the lump-sum funds without any conditions for implementation. If USAID had tried to make the project more transparent from the beginning, however, the Egyptian governmental authorities would simply have said they didn’t want it.30

The TDA thus continued to distribute land throughout the southern Red Sea as if there had been no laboriously agreed-upon master plan. When project managers complained that the plan was clearly overlooked in the rapid tourism development on the coast, newly appointed officials claimed ignorance of their predecessors’ decisions.31

Managerial networks were somewhat more successful in leveraging donor assistance to build institutional capacities within the Nature Conservation Sector itself for the Red Sea zone. Between 1999 and 2003, the number of employees working in the Red Sea marine zone increased from twelve to fifty-four, most of whom were park rangers (Colby, 2002: 11). In 2003, USAID reported that it financed 95 percent of the Red Sea protected area unit’s operating costs for the year, including employing three Egyptian conservation experts to staff the program management unit (Abdel Razek, 2003: 14). USAID’s LIFE project also supported upgrading of tribal settlements in and around the southern Red Sea protectorates, providing training and marketing in local handicrafts, and the provision of basic services, such as generators and solid waste collection.

By creating a staffing and management presence in the Red Sea protectorates, donor funds helped the NCS attract centrally allocated budgetary resources. The EEAA expenditures on the Red Sea protectorates kept pace with USAID spending; between 1999 and 2003, USAID spent US$1.1 million on the Red Sea protectorates, while the EEAA spent US$1.2 million (Abdel Razek, 2003).

These investments, however, were not sufficient to meet the expanding needs of protectorates in trying to safeguard coastal habitats. As the only institutional presence responsible for enforcing Egypt’s major environmental laws (Law 102/1983 and Law 4/1994), rangers were charged with a diverse and expanding set of tasks that included monitoring protected areas, reefs, and islands, enforcing no-fishing zones in cooperation with the Coast Guard, responding to visitor needs, liaising with local communities, and other tasks (Colby, 2002: 3). In 2002, the then-director of the Nature Conservation Sector, Mustafa Fouda, and a working group of Red Sea rangers estimated that, for the Red Sea protectorates to be managed adequately, total expenditures needed to increase from approximately US$1 million per year (shared between USAID and the EEAA) to US$4 million (ibid.).

Within the Red Sea protected areas, environmental experts working with the NCS and donor projects found the protectorates’ legal authority over the land increasingly challenged by the military, security forces, and the TDA. For example, USAID’s LIFE project enlisted well-known Egyptian conservation experts, such as the ornithologist Sharif Baha El-Din, to devise a coastal sensitivity mapping protocol for the Gabal ‘Elba Protected Area, which borders Sudan on the southern Red Sea coast. Conservation experts wanted to devise a protocol that rangers could use to rank areas of critical biodiversity and ecosystem importance. As USAID contractor Chemonics International noted, “The activity was given high priority because coastal areas in the Elba PA [protected area] had been purportedly sold to developers by the TDA” (Chemonics International, 2007a). After an initial mission to the area, the joint team of Egyptian experts and park rangers were denied permission to return by the security services. Thwarted in their attempt to map the ‘Elba coastline, the team instead conducted a pilot mapping in a section of the Wadi al-Gamal Protected Area that the TDA had sold to developers (Chemonics International, 2007b).

One of the greatest challenges to attempts to build management capacities in the Red Sea protected areas was thus the property claims of the TDA itself. For instance, USAID attempts to build a visitor center and ranger operation center in Wadi al-Gamal National Park provoked long negotiations with the TDA, which claimed it owned the land. The resolution of this inter-agency conflict confirmed the TDA property claim, as a report by a USAID contracting firm noted: “The TDA agreed to give the EEAA a ninety-nine-year concession to use the land, without charge, so the structures could be built” (Chemonics International, 2008: 10). The TDA further allowed resort development within the boundaries of the Wadi al-Gamal Protected Area itself. By 2011, the Gorgonia Beach Resort offered guests 350 rooms, three restaurants, six bars, a theater, a disco, four swimming pools, excellent sports facilities, and 700 meters of white sandy beach, all inside the protected area.32

As in Sinai, the social and environmental impacts of tourism development were not adequately addressed. Resort construction, intensive diving, and oil contamination contributed to a reduction in coral cover of up to 30 percent in some portions of the Red Sea reefs (Pilcher and Abou Zaid, 2000). In one of the first areas to be developed, the town of Hurghada (al-Ghardaqa) on the Red Sea coast, investors built forty-two major recreational resorts and seventy private or individual projects (Frihy et al., 1996: 324). Egyptian marine scientists found extensive ill effects upon the coastal reef ecosystems, stemming from dredging, the construction of artificial beaches, lagoons, marinas, jetties that altered the coastline, and inadequate handling of solid and liquid wastes (El-Gamily et al., 1997; Frihy et al., 1996). The researchers concluded, “Irrational projects implemented with improper designs have progressively created deterioration of the coastal ecosystem” (Frihy et al., 1996).

Also as in Sinai, local tribal land use claims were overlooked, tourism employment excluded local residents, and public services for expanding municipalities were entirely inadequate. In 2008, a USAID-funded report observed that “local residents made up only 3 percent of the tourism workforce industry in the Red Sea governorate” (Chemonics International, 2008: 21). Tourist establishments linked to the municipal network did not pay sewage costs, and resorts were not required to create or subsidize the construction of landfills. Municipalities faced serious budget constraints in establishing public services for trash collection and disposal, and resorts paid for private collection trucks that then dumped trash anywhere. Piles of trash, particularly plastics of all sorts, dumped in streets, wadis, and vacant lots in the backs of houses, was thus the most visible sign of failed public service provision. As one reporter wrote in 1997, “Lack of clean water, adequate housing, managed waste collection, and reasonable wages have locals bearing the brunt of tourism growth” (Marsh, 1997).

Activist conservation networks in the Red Sea

Environmental degradation in and around Hurghada eventually sparked the creation of an activist conservation network based largely on the concern of dive operators to protect the reef systems on which their livelihood depended. A handful of resident foreigners and Egyptians that owned and operated dive centers and live-aboard diving boats thus founded the Hurghada Environmental Protection and Conservation Association (HEPCA) in 1990. Unlike most environmental organizations in Egypt, HEPCA drew upon fee-paying members to support its advocacy and activities. The organization accepts only institutional members that pay annual dues of LE1,200. As of 2011, members included dive centers and live-aboard diving boats, a few resorts, restaurants, international tourism operators, and the Suweiris’ construction firm Orascom.33 In addition, USAID and several Egyptian companies found funding the organization attractive as part of their broader efforts to promote environmental awareness in “the private sector.”

HEPCA’s first initiative was to install a mooring system for boats to safely anchor near coastal and island fringing reefs. Increasing numbers of dive boats had extensively damaged the reefs; without moorings in place, boats simply dropped anchor on the reefs. Supported by USAID and member dues, HEPCA had installed 1,064 moorings along the Red Sea coastline by 2011. It currently produces the moorings locally and has exported the product to other Red Sea states, notably Jordan and Saudi Arabia.

By 2004, the organization began experimenting with direct environmental advocacy. The TDA had awarded Italian investors an entire island, Giftoun, off the Hurghada coast, for tourism development. HEPCA coordinated the Hurghada diving community to go on strike, and launched several public street protests that received significant media attention. As in the popular campaigns against the fertilizer plant in Damietta, media coverage proved an effective means to capture the attention of the highest levels of the Egyptian regime. Shortly thereafter, Mubarak issued a presidential decree banning the sale of entire islands.

Emboldened, the organization began to take the TDA to court over its land use allocations, as the EEAA legal department had tried to do as well. As a member of HEPCA observed in 2011:

there are 806 kilometers of fringing reef along the Red Sea coast and therefore there are 860 kilometers that the TDA is trying to develop. Just in the 200 kilometers between the cities of Quseir and Marsa Allam on the southern Red Sea coast, there are 3,200 rooms in TDA projects.34

The organization filed seventy-six cases against the TDA between its founding in 1990 and 2011. In its legal filings, HEPCA tried to establish that coral reefs constituted “productive public property” in order to extend protections present in Egyptian law for agricultural land.

In order to build infrastructural authority for conservation along the Red Sea coast, HEPCA initially sought cooperative relationships with the NCS. As noted by most environmental experts, however, during the 2000s the NCS, like the environmental agency as a whole, saw top staff positions increasingly drawn from the ranks of ex-military and internal security men. “The minister kicked out many of the scientists and brought in ‘trustworthy’ generals,” argued a HEPCA representative. “We’ve seen the national park authority falling apart, so we have tried to step in where we can.”35

To compensate, the dive operators’ organization worked more closely with the existing managerial conservation network to undertake specific conservation initiatives along the Red Sea. HEPCA’s 2011 advisory board reflected this mix of activists and experts. It included the former director of the NCS; the primary Egyptian consultant to USAID’s Egyptian Environmental Policy Project; one of the leading businessmen advocating for ecotourism through newspaper and media work; two resident foreigners that founded early dive centers in the Red Sea; and an outspoken local entrepreneur who has developed two environmentally friendly dive resorts in the Red Sea.

As protected area managers had sought to do in Sinai, HEPCA’s board tried to inform and educate governors on the economic value of marine conservation. In doing so, they were able to get official support for initiatives like an official decree banning the use of plastic bags in the Red Sea governorate. HEPCA also sought to build infrastructural capacities on the ground. The association purchased a few fast, small boats to conduct patrols of the coastline to supplement the woefully inadequate patrols conducted by the Egyptian Coast Guard and Navy. They hired ex-generals as consultants, to help navigate the rocky shoals of competing personal and bureaucratic interests of the Red Sea governorate, the Navy (responsible for Red Sea offshore islands), and the Coast Guard, with jurisdiction over the coastline to three miles out. They used the international and local press to publicize cases of environmental damage and violations. HEPCA also tried to provide direct support to rangers working in the Red Sea protectorate, bypassing the central environmental agency, just as the former head of the NCS had also tried to do. When rangers received more lucrative offers to work in the Gulf, for example, HEPCA found some of them alternative employment with the organization to keep them in Egypt. Lastly, HEPCA eventually also moved into providing solid waste collection and recycling to address the pressing solid waste problem in Hurghada. By 2011, HEPCA was the sole contractor with the Hurghada municipality for trash collection, separation, and disposal, employing 896 people in total.

For most of HEPCA’s activities, governmental entities remained necessary counterparts even as they were often obstacles to implementing initiatives. As a HEPCA member observed:

You cannot simply get into a conflict with the government. You need to find someone in the government—one side of a triangle—to help neutralize objections from other parts of the government. You need to have at least one part of the government in the boat with you. So that when the conflict goes to the top, it is not a conflict between an NGO like ours, and the government, but between government agencies.36

HEPCA was thus a new kind of conservation interest group in Egypt, prompted by the interests of the diving business community in trying to slow degradation of Red Sea reefs. HEPCA’s work highlighted how activist campaigns need not be restricted to the kinds of popular movements in urban areas analyzed in the previous chapter. The institutional members shared a clear economic stake in reef protection. Through coastal patrols, solid waste operations, autonomous financial resources, and an ongoing (if conflicted) relationship with governorate officials and generals, the association wielded some infrastructural authority to influence outcomes along the Red Sea.

Activist campaigns for protected areas

HEPCA was not the first voluntary association to campaign on behalf of protected areas. Efforts by the EEAA legal department to litigate against violations in and around protected efforts were widely publicized and set a precedent for environmental associations to follow suit by the late 1990s. As the existence of protected areas (mahmiyat) became more widely known, the legal framework governing protected areas became increasingly recognized as an avenue to contest unpopular land uses in general. A letter in the government-owned daily newspaper Al-Ahram in 1998 provided a humorous example: the correspondent noted that since the ex-Minister of Tourism had allowed several villas to be built on the grounds of Alexandria’s Muntaza Palace, supposedly a public park, the palace grounds should be declared as a protected area if they were to be salvaged (The “Green Man,” 1998).

Several NGOs employed Law 102 to sue the environmental agency and provincial governors for mismanaging formally designated protected areas. In the case of Wadi Sannur in Bani Suwayf, the Land Center for Human Rights sued the environmental agency in 1997, claiming that the agency had not enforced restrictions on illicit quarrying in the protectorate’s marble caves (Saber and Abu Zeid, 1998). The Land Center’s network of lawyers and activists hailed from an array of leftist opposition perspectives; most had worked on human rights campaigns or in union and labor activism in the 1980s and 1990s.37 The Land Center filed several cases on behalf of whistleblower rangers, injured workers, and the Bani Suwayf Local Council, citing the governor and the EEAA as defendants and seeking compensatory damages.

Another network of activists coalesced around threats to Wadi Digla, a canyon located on the outskirts of Ma‘adi, the tiny suburb at Cairo’s southeastern edge. After a campaign by the Tree Lovers’ Association, a local group based in Ma‘adi, whose residents used the geologically rich area for hiking and school trips, the wadi was declared a protected area in 1999. The head of the association reportedly enjoyed cordial relations with the regime, helping to usher the case through the EEAA to the Cabinet (Stanford, 1999). The EEAA hired several conservation experts to survey biodiversity in the area and propose boundaries for the new protectorate. Yet the maps and field studies produced were not used; instead, the protectorate was designated as a long and narrow area difficult to protect from encroaching land uses and illegal waste dumping.38

The Wadi Digla protected area directly abuts Shaqq al-Thu‘ban, a complex of approximately 400 small-scale factories that represent 60–70 percent of all marble working in Egypt, employing up to half a million workers (Elmusa, 2009: 191). Existing workshops were grandfathered into the buffer zone of the protected area but, in 2006, new marble factories were licensed under a protocol between the EEAA and the Ministry of Industry (ibid.: 191). The protocol did not include provisions to contain or dispose of slurry and dust generated from quarrying, cutting, and transport, or the solid waste produced by the factories. Plastic bags and other trash from the factories, a nearby recycling center, and inadequate solid waste disposal blew into the wadi (ibid.: 192). As on the Red Sea coast, plastic waste proved a significant threat to local fauna and increasingly destroyed the aesthetics of desert landscapes. Despite ongoing activism on the part of the Tree Lovers’ Association and other concerned citizens, Wadi Digla remained encroached upon and increasingly polluted.

In these local campaigns to protect specific protected areas, Egypt’s managerial conservation experts did not play a significant role. Some members of Egypt’s conservation network eventually created their own association, Nature Conservation Egypt, which they formally registered with the government in the late 2000s. The group did not engage in significant activism until 2011, however, when risks from tourism investment in and around protected areas in the Fayoum oasis intensified and Egypt’s January 25 uprising offered new possibilities for mobilization, as discussed in the concluding chapter.

An autonomous authority for protected areas?

The erosion in top leadership and institutional capacity that characterized the EEAA during the 2000s, analyzed in Chapter 2, also impacted the EEAA’s Nature Conservation Sector. President Mubarak’s political appointees from the police, military, and security forces were widely regarded as ineffective advocates for conservation, and unable to counteract the political appeal and economic benefits associated with tourism development. The NCS found itself chronically underfunded, understaffed, and hampered by the standardized, cumbersome, and centralized procedures governing Egypt’s governmental institutions.

At the same time, visitation rates to Egypt’s protected areas had skyrocketed. Between 2003 and 2008, 1.6 million tourists visited Egypt’s protected areas, with an annual average increase of 9.5 percent (Global Environmental Facility, 2010: 14). Of these visitors, 47.1 percent went to the Red Sea, 22.1 percent visited the reefs at Ras Mohamed, and 20.1 percent headed to the South Sinai interior of St. Catherine (ibid.). During the same period, the protected areas generated LE17.3 million in entrance fees, even though entrance rates were kept at a mere US$3–5 for foreigners and LE2–5 for Egyptians (ibid.: 15).