I don’t give advice. I can’t tell anybody what to do. Instead I say this is what we know about this problem at this time. And here are the consequences of these actions.

People don’t buy what you do, they buy why you do it.

Ethics are highly conceptual and abstract, but the actions that you take to design and execute big-data innovations in business have very real consequences. Damage to your brand and customer relationships, privacy violations, running afoul of emerging legislation, and the possibility of unintentionally damaging reputations are all potential risks.

Big-data ethics stand in roughly the same relationship to organizational success as leadership and management: both are simultaneously abstract and highly influential in building and maintaining successful organizations. And both are deeply informed by values.

As detailed in previous chapters, ethical decision points can provide a framework and methodology for organizations to facilitate discussion about values and can help resolve conflicts about how to align actions with those values. In other words, they help align your tactical actions with your ethical considerations.

Learning how to recognize ethical decision points and developing an ability to generate explicit ethical discussions provide organizations with an operational capability that will be increasingly important in the future: the ability to demonstrate that business practices honor their values. This is, undoubtedly, not the only framework that can help, and it is also not a “magic bullet.” Other organizational capabilities are required to support those business practices.

Fortunately, organizations already have many of those capabilities. Combined with traditional organizational capabilities—leadership and management, communication, education and training, process design and development, and strategic initiative development and execution—a responsible organization can use this alignment methodology to identify their values and execute on them.

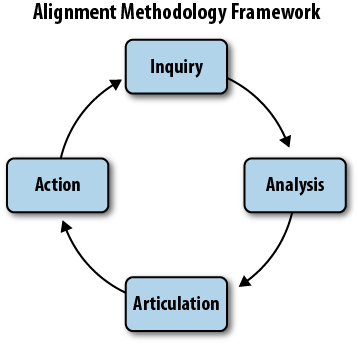

These activities are more organic than strictly linear; ethical inquiry will interact with the analysis work. It may turn up insights that lead to a re-articulation of an organization’s ethical position, while further analysis of those principles may uncover strengths or weaknesses in an organization’s existing data-handling practices.

A responsible organization’s goal is to identify, document, and then honor a common set of values by executing processes and business practices that are in alignment with those values. By combining existing skills and resources with this approach, organizations can grow their capacity to engage and manage any ethical challenges that big data generates.

But remember that it can be tempting to avoid the discussion entirely. And the politics of power in an organization can be complex to navigate. Roles including compliance or ethics might have the primary responsibility of making values and actions transparent, whereas other roles, such as legal or human resources, might be highly concerned with the implications of alignment failures. The tension there is not always easy to resolve. One purpose of the methods and tools described in this chapter is to introduce new ways to get the right people in the room to collaborate on resolving those tensions together.

Because ethics is an inherently personal topic, ethical discussions often expose conflicting values. To reduce the potential conflicts, it helps to focus on the common benefits that values-to-action alignment can bring—both to individuals and organizations. Operational efficiency, the reduction of risk, creating space for individual contributions, and stronger external relationships with partners and customers are all benefits that derive from clarity of the values that drive the execution of organizational action.

In framing up workshops or other meetings for these discussions, the strongest source of motivating participation, regardless of the role, is to help drive innovation. The rapid pace of changing market conditions, in nearly every sector of the economy, is making innovation one of the most powerful competitive tools available. Some even argue that innovation is the primary driver of economic value (http://blogs.valvesoftware.com/abrash/valve-how-i-got-here-what-its-like-and-what-im-doing-2/).

And, while focusing on innovation can be a risky business, the desire to help others reduce that risk and create new economic value is often a deeply held personal value. Finding the common ground for entering into ethical discussions is often half the battle. It is frequently a matter of asking the right question or framing the inquiry in the most accessible way. In most cases, if you ask people what they want, it turns out they will tell you. So when faced with resistance to participating in or using these methods and tools, seek out the needs and goals of the individuals who can contribute to the discussion. Understanding the common purpose will reduce a significant amount of resistance and dissolve a wide variety of tensions.

Even then, however, it’s not always easy to navigate the complexities of organizational politics. And although these methods and tools can be used by anyone, at any level of the organization, it is often helpful to have a neutral third-party facilitator or to engage an outside perspective or resource to help identify landmarks and pitfalls. In either case, the goal is to just start the discussion. The best practice is to consider it an ongoing process, not a singular event. There may be one or more discrete activities (workshops, meetings, discussions, etc.), but when taken together and viewed in the context of the framework, those activities form a new organizational capability that is becoming increasingly important.

The ecosystem of activities can be viewed as a “virtuous circle” of influence that can be entered at any point, is informed by the findings and insight of the previous set of activities, and subsequently informs the work in the next set. It is worth noting that this methodology is not strictly a checklist. Although there are discrete sets of activities, they influence and inform each other as they unfold.

This methodology is not intended to tell you what is ethical for you or your organization. Circumstances, culture, market, economic conditions, organization size and purpose, and a vast array of other factors make it very difficult to develop a common set of values that would work well in all contexts. Even current efforts to create a “digital bill of rights” or “data-handling manifesto” struggle to be relevant and directive enough to inform specific action. They are also open to wide interpretation. This methodology gives you some tools to get very specific about your values and how to align them with very tactical actions that are directly relevant to your highly specific context. It is a place to start.

As briefly introduced in Chapter 2, the four core components are: Inquiry, Analysis, Articulation, and Action.

- Inquiry

Discovery and discussion of core organizational values

- Analysis

Review of current data-handling practices and an assessment of how well they align with core organizational values

- Articulation

Explicit, written expression of alignment and gaps between values and practices

- Action

Tactical plans to close alignment gaps that have been identified and to encourage and educate how to maintain that alignment as conditions change over time

The foundation of ethical inquiry stems from a basic understanding of whether actions and business practices are aligned with values by first exploring exactly what those values are. Because big data’s forcing function interacts with a broad spectrum of your customers’ lives, the subsequent range of values it can influence is equally broad, and it can be hard, messy work to uncover a foundational set of values more meaningful than mere platitudes.

While a mission or organizational values statement can serve as a guide for an organization’s purpose, ethical inquiry seeks to understand the set of fundamental values that drive subsequent organizational action. The outcome of which is an understanding and articulation of those values that is more detailed and nuanced than a traditional mission statement.

To help get to a place where those values are being discussed authentically, here are some opening questions:

Are people entitled to know how their data is used in the business?

Are people entitled to know which organization holds their data and what data in particular it holds?

Are people entitled to know how their data is analyzed and how the results of these analyses drive the business?

Are people entitled to know who within the organization has access to the data?

Are people entitled to know to what third parties the data is transferred (sold, given, released publicly, etc.)? If so, is it the organization’s responsibility to let those people know what these third parties will do with the data? (That is, is it the originating organization’s responsibility or a receiving organization’s further down the data trail?)

To the extent that people do have the previously listed entitlements, what constitutes sufficient notice to them of the relevant facts? May they be buried in long End-User License Agreements (EULA) that few people will read?[6] Must those entitlements or license agreements be explained clearly in everyday language, or is it the responsibility of the end users to distill the legal language into something they can understand?

In general, should data collection occur through an opt-in or an opt-out model? Should other things, such as long-term storage or transfer to third parties, be opt-in or opt-out?

What data raises the most organizational risk? What is required to determine the risk-benefit ratio of not collecting that data?

Do data-handling practices generate external influences that specific values demand not be created? (Examples could be social networks diminishing real-world relationships or music recommendation services reducing the ability to make discerning judgments.)

Do data storage practices—even if the data collection involves infringing on no particular ethical values—create a resource that would be of use to powerful negative forces in the world, such as malicious or misguided governmental organizations, organized crime, or nefarious hackers? Is a responsible organization acting unethically if it does not have a definitive perspective on this question?

At least a preliminary set of answers to these types of questions will help identify what values you hold and begin to uncover what data-handling actions you make in accordance with those values.

It is preferable to start with the general and move toward the specific—to the degree of precision and articulation your unique circumstances allow. And they may not allow for much. Given an expectation that data-handling practices and values may evolve over time in response to changes in market dynamics, technology innovations, or broad changes in strategic business direction, they do not need to be carved in stone. It is sufficient at this stage to express these values as a set of general guidelines.

Ethical decisions are complex by their very nature, and perspectives and opinions vary widely among individuals. They vary even more when organizational imperatives from management, investors, or the marketplace (e.g., demands to operate profitably) are included in the mix. And this is precisely why an explicit and focused exploration of a shared set of common values is useful.

That said, the motivation isn’t “we should explore values because it’s difficult.” The motivation is that you should explore them because big-data technologies are offering you an opportunity to operate in more beneficial ways and to generate more value in doing so: ways that apply to individuals, organizations, and society at large as the result of maintaining a healthy and coherent balance between risk and innovation—and between values and actions.

Those benefits were mentioned in Chapter 2, but are worth highlighting here. Specifically:

- Reduction of risk of unintended consequences

An explicit articulation of a shared set of common values isn’t going to answer every possible future question for working teams. But this articulation will significantly reduce the amount of overhead discussion required to develop an action plan in response to an event.

- Increase in team effectiveness

A shared set of common values reduces operational friction in precisely the same way a political initiative or social cause benefits from the shared beliefs of its members. When designing products and services using big data, even a general, preliminary agreement about what’s OK and what’s not among team members greatly improves a communal ability to focus on solving problems—rather than conducting an ethical debate about which problems to solve.

- Increased alignment with market and customer values

The business benefits of acknowledging and explicitly articulating organizational values and how they align with customers derive from the same increase in cohesion as shared values in internal teams. People who value the same things often work better together. Organizations who understand their customer or constituent’s values are better able to meet them—resulting in greater customer satisfaction and deeper, more meaningful brand engagement.

As we saw in Chapter 3, however, values and actions are deeply intertwined.

Consider your own actions in daily life. They are, in part, motivated by your values. Perhaps some not as deeply as others, and there are often trade-offs to be made and balances to be maintained. People who value sustainable lifestyles may nonetheless choose to drive to work in order to support their basic need to generate income. Seeking an acceptable balance, they may elect only to ride bicycles on the weekend. Eating a healthy diet or exercising aligns with personal health values.

In every case, however, making those trade-offs and maintaining that balance is impossible without first understanding, explicitly and authentically, what values are in play. And the broad influence of big data’s forcing function is widening the scope of inquiry every day.

The goal of ethical inquiry is to develop an understanding of organizational values. The next step, analysis, is to determine how well actual data-handling practices are in alignment with them. This analysis can be more complex for an established organization than it is for a proposed startup (which typically do not, it is fair to assume, have mature plans for unintended consequences or employee failures to act in accordance with company policy).

Big-data startups can exploit an advantage here. By understanding core values in advance of building out their operational processes and technology stack, they can actually take action to build their values directly into their infrastructure. In some ways, an organization’s technology configuration, business processes, and data-handling practices can be viewed as a physical manifestation of their values.

General topic themes are a good start. As a reminder, many organizations already have mature business capabilities that can contribute much to inquiry and analysis. Compliance, human resources, legal, finance and accounting, data architecture, technology and product planning, and marketing all have unique and informed perspectives.

Consider the specific examples: discussed next: data-handling audits and data-handling practices.

A key task in the evaluation of your current practices is a thorough audit of data-handling practices. A wide variety of organizational or business units touch many aspects of data handling. A rigorous audit will include process owners from each business group involved in any aspect of how data is handled. Considerations include:

Who within your organization has access to customer data?

Are they trustworthy?

By what methods have you determined them to be trustworthy?

What processes are in place to ensure that breaches of trust will be noticed?

What technical security measures are taken with data?

Are they sufficient for the purposes?

Who outside of your organization might be interested in gaining access to the data you hold?

How strong is their interest, and what means might be at their disposal to breach your security?

A responsible organization will conduct a thorough audit aimed at answering such questions. Traditional workshop and audit tools and processes can be useful in this work.

- Process maps

A data ethics audit team will benefit from a process diagram and associated task lists for how data is acquired, processed, secured, managed, and used in products and services.

- Facilitated workshops

It is far more efficient and more likely to uncover gaps and overlaps in data-handling practices by gathering a core team together to work through a series of audit exercises. These exercises should be designed to discover and explore the ways in which organizational values are—or are not—being honored in data-handling practices.

- One-on-one focus interviews

This activity is best used to supplement facilitated workshops and to uncover more candid concerns about values-actions alignment. Focus interviews are aimed at discovering how people handle data, the extent to which they understand and share the organization’s values, and whether those practices contain any weaknesses.

- Security reviews

There is an entire field of expertise and discipline centered on information technology security. A responsible organization utilizes experts in this field to generate a deep understanding of their data security systems and practices.

- Attack scenarios

Facilitated exercises to explore and imagine various attack scenarios can generate massive insights into how well existing data handling practices would stand up to specific efforts to access customer data. These exercises are most successfully conducted in a cross-functional group where visual thinking and collaborative problem solving are key tools. Executed well, gaps and overlaps in data-handling practices can be uncovered quickly and efficiently.

- Aggregation audits

There is a growing realization that personal information can, in unfavorable circumstances, be the missing link needed by someone who intends to do harm by connecting people to information that may have an ethical impact.[7] A responsible organization will ask itself under what conditions their customer information would actually be useful to anyone seeking to correlate previously disaggregated data sets—whether with the intention of doing harm or not.

- Risk/harm scenarios

What sorts of harm can your organizational data do—either by itself, if exposed, or by correlating or aggregating with any other imaginable data set? This question might be more easily answered if you run an anonymous offshore social network for dissidents in an authoritarian country and more difficult to answer if you run a site for local music reviews.

Here is a clear example of where inquiry and analysis are deeply intertwined. If organizational values support a strict and 100% anonymous ability to connect and communicate with other people, it is natural to imagine that organization’s data-handling practices will support those values by implementing extremely rigorous security and other handling procedures.

- Internal conflicts

Individuals can certainly hold views that conflict with organizational values. While the broader purpose of the entire cycle of Inquiry, Analysis, Articulation, and Action is intended to align values and actions both internally and externally, understanding where individual and organization values conflict (or are out of alignment) is key to closing those gaps. Value Personas, discussed later in this chapter, are a useful tool to facilitate this understanding and alignment.

- Surveys

Online surveys of customers or internal teams are also useful at this phase, with the understanding of the natural strengths and limitations of surveys generally. Survey responses may be a result of misinformation or misunderstanding of what an organization actually does with customer data. It may be difficult to craft the right questions on such conceptual and nuanced topics. Surveys are, however, a well-established research mechanism to gather large amounts of information in a short period of time and are a valuable arrow in the data ethics audit quiver.

The promise of benefits from big-data innovation needs to be balanced by the potential risk of negative impact on identity, privacy, ownership, or reputation. In order to maintain that balance, organizations must understand their actual data-handling practices—not what they think they are or what an outdated process diagram says they are. This requires a thorough consideration of how those practices influence each aspect of big-data ethics: identity, privacy, ownership, and reputation.

For a responsible organization, this is not a matter of an arbitrary “what if?” session. It is a matter of gathering real, accurate information about any methods or resources that might expose information about which there are ethical implications—and the likelihood of this happening.

The goal is to take a clear look at what is done with data within the organization and to describe the actual practices (not merely the intended or perceived ones) accurately so as to facilitate rigorous analysis. An open, inclusive approach including all relevant personnel will provide greater insight into the sensitivity of the data one’s organization holds. Consider the extent to which any single individual may ordinarily be unaware of the details of the data process that drive the implementation of their business model. Including dross-functional roles in this discussion helps to expose and close any gaps in any one individual’s understanding and generates a more robust and complete picture of the operational reality.

The complexity of targeted advertising is a prime example, not to mention a likely familiar use case to many businesses. It is a complex business activity typically involving multiple individuals and technologies within an organization, close data-sharing partnerships with other organizations, multiple web properties, and dozens (or possibly hundreds) of content producers and consumers. This complexity raises familiar issues of third-party usage of personal data, privacy, ownership, and a growing realization that major big-data players often are not entirely transparent about how their applications are interacting with your data.

For example, in February 2012, the New York Times reported on news that the mobile social networking application “Path” was capturing and storing ostensibly private information (contact information on mobile devices, such as names, phone numbers, etc.) without notifying people (http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/02/12/disruptions-so-many-apologies-so-much-data-mining/).

The resulting responses ranged from ethical comments (from the Guardian: “It’s not wrong to store someone’s phone contacts on a server. It’s wrong to do it without telling them”[8]) to the realization mentioned in the article that the mere location of data influenced how much protection the First Amendment could actually provide.

Banner ads are a common targeted advertisement technique, and many people strongly dislike seeing banner ads for products based on their browsing history—especially when those advertisements seem irrelevant. Some might argue that since people are going to see some ad, it might as well be a targeted one because even poorly targeted advertising based on browsing history is bound to be of more interest to consumers than ads published merely at random. Yet the practice, even when entirely automated, still raises the suspicion that third parties know where they have been browsing specific content and then passing that information to others for a fee.

Targeted advertising today is maturing and improving accuracy at a rapid pace. But there are still potentially negative consequences based on the perception that there is something wrong with it. In February 2012, the Wall Street Journal reported that Google was embedding software on some websites to circumvent a default setting on Safari web browsers in order to target advertising (http://online.wsj.com/article_email/SB10001424052970204880404577225380456599176-lMyQjAxMTAyMDEwNjExNDYyWj.html#articleTabs%3Darticle). Google responded with a statement that said their intention was benign and they did not collect any personal information. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) responded with an investigation. In July of 2012, Bloomberg reported that the fine is expected to be a record $22.5 million (http://www.bloomberg.com/article/2012-07-10/a4ZIufbs2jko.html).

The message is clear: a responsible organization must decide for itself how far it must extend its data-handling practices in order to honor its values. The complete data exhaust trail of big data can reach dozens, even hundreds, of other organizations. A thorough understanding of which third parties have access to your organization’s data (through sales, storage, sharing, or any other means) must be developed and documented up to and including the point your values dictate.

Considerations include:

With whom do you share your data?

Is it sold to third parties? If so, what do they do with it, and to whom do they in turn sell it?

Do you release it publicly at times? If so, how strong are your anonymization procedures?

Who might be motivated to de-anonymize?

Who might partially de-anonymize by correlating your data with other data?

How likely would any aggregation lead to harm?

Answering these questions requires a thorough understanding of the sorts of correlation, aggregation, and de-anonymization that are possible with your customers’ data, and likelihood and the possible motives others may have to do so. (http://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2010/03/de-anonymizing.html). Data sharing, whether intentional or inadvertent, requires a thorough knowledge of the data landscape and technical issues of a wide variety of aggregation possibilities, paired with the sociological, psychological, and economic factors relevant to understanding their potential actions.

For example, third parties with access to customer data may be hesitant to share information about their own practices, citing a variety of constraints such as competitive intelligence, intellectual property, or their own value system. While this hesitation itself is not sufficient cause for concern, a responsible organization may honor its values by inquiring whether third-party data-handling practices align with their own.

Analysis at this stage should also include consideration for any long-term external effects data-handling practices might have—especially those with ethical implications. How would widespread adoption of your product or service affect the quality of people’s lives? In order to discover the extent of those implications, it helps to get informed opinions from a broad array of existing functional areas in the business, especially those familiar with your particular business model.

There may also be external implications from either the long-term effects or the large-scale use of available data. Exploring these implications requires consideration of relevant principles in a wide variety of areas: finance, marketing, data security, law, market conditions and economics, and social psychology. As data sharing extends beyond organizational boundaries and control, a broad range of factors may affect operational processes in actual practice. A responsible organization may find that the data exhaust trail of their data practices has surprisingly far-reaching consequences.

The outcome of inquiry and analysis activities is dependent on many factors.

Considerations include:

Type of organization

Roles and responsibilities of the participants

Duration and complexity of the process

Complexity of the data ecosystem and technology stack

Industry or market of operation

These considerations, and many others specific to your particular circumstances, will all influence the format and content of the results. And this variety of outcomes is to be expected. No two businesses are exactly alike, and no two organizations’ values systems and subsequent actions are likely to be identical either. Generalities and comparisons can often be made, but the circumstances under which ethical values inform your organizational actions are unique.

Generally, however, inquiry and analysis activities result in a set of findings and insights captured in document or visual form, such as:

Provisional statement of organizational principles

Security audit findings

Data-handling processes and polices (in written and visual form)

Documents describing the sensitivity, use, and sharing of held data

Insights into practices of similar organizations (industry norms)

External implications and current insights and perceptions on their degree of risk

Gaps and overlaps in values-actions alignment

The goal of Articulation is to answer this (admittedly difficult) question: are your organization’s practices (actions) in alignment with its stated principles (values) or not?

On the one hand, inquiry and analysis may demonstrate that the set of identified values needs revision. On the other hand, the organization’s values may be found to be basically acceptable to the organization as they stand, and current data handling practices found wanting and requiring adjustment.

The tools that are available to articulate values-to-action alignment are:

Ethical principles in the form of value statements (the results of Inquiry)

Explicit analysis and documentation of existing practices (the results of Analysis)

Based on previous inquiry and analysis, a wide variety of possible scenarios might be uncovered. Security may be insufficient given the sensitivity of held data. A specific data collection process may be out of alignment with certain values. Refusal of third parties with access (either paid or not) to data sets to describe their own practices may warrant discontinuation of business with those third parties.

The goal of these activities is to generate and express an agreement about what an organization is going to do—that is, what actions it will take in alignment with which values.

Your organization can move from the highly conceptual, abstract nature of values and ethics to a useful and tactical action plan by identifying gaps (misalignment between values and actions) and articulating how you intend to gain and maintain alignment.

Inquiry and analysis will inform this articulation, and discussions across the organization, including as many viewpoints and perspectives as possible, can provide additional insight on existing and evolving practices. The intention is to generate explicit discussion. Books, articles, emerging legislation, news reports, and blog entries on existing norms and practices for your industry or of similar organizations are a rich source of generating a comprehensive, comparative view of data-handling practices.

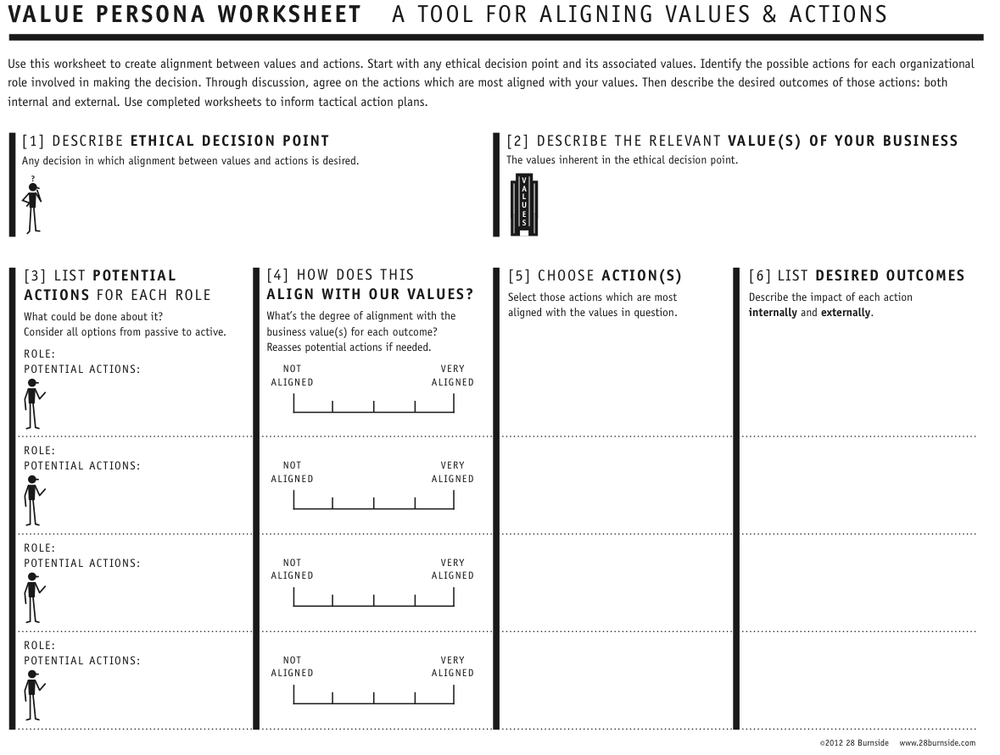

To implement those actions, a Value Persona (explained in the next section) can be a helpful planning tool. And you’re now in familiar territory: running programs and projects, setting and tracking milestones, and measuring performance against defined benchmarks. Value Persona worksheets can help you discover a wealth of information about how your organization intends to navigate ethical waters and can be used in parallel with more familiar tools, including project and action plans, communication plans, improved business processes, education programs, or revised hiring strategies.

Some examples of ethical decision points where a Value Persona might be useful:

Adding a single new feature

Policy development

Security breaches

Designing an entirely new product

Designing an entirely new set of product features

Opportunity to benefit from combining two distinct data sets

As a tool to help aid in the articulation of those values and the subsequent organizational actions, Value Personas offer a means for facilitating discussion about organizational alignment in actions, business practices, and individual behaviors based on a common set of values. They contain a description of key roles, any ethical decision points, alignment actions, and anticipated outcomes. They help to identify shared values and create a vocabulary for explicit dialog, thereby reducing risk from misalignment and encouraging collaboration and innovation across working teams.

The use of audience (or user) personas is a common methodology in advertising, user experience design, and product and market research. In traditional practice, attributes are associated with a hypothetical individual for the purpose of segmenting audiences into predictable behaviors and needs.

Value Personas are an evolution of traditional user personas that express how a specific value shows up and influences action within an organization. Value Personas shed light on moments when the use of big-data technologies raises an ethical (or value-focused) decision point. A Value Persona can suggest options for how to align shared values with proposed action from various organizational role perspectives.

Value Personas are developed using persona worksheets. The worksheets provide a working space for notes, drawings, sketches, illustrations, and remarks as teams work through the details of building an effective action plan to achieve alignment.

Value Personas provide a means for framing up explicit ethical inquiry and are highly flexible and amendable to many given contexts.

They assume several things:

First, values do not take action; people do. It is only through action that values show up. And, as discussed earlier, your values are inherent in your actions all the time. The benefit of the Value Persona is to identify and document which values are showing up in your actions—and how.

Second, values can be intentionally aligned with actions. Although it is true that an individual or an organization can hold conflicting values—which can result in conflicting actions—the Value Persona can help make those conflicts transparent.

Finally, values are not ethics. Ethics are derived from values. Ethics are expressions of which actions are valued and which are not. Values are a measurement of whether those actions are ethical. The Value Persona is the stick by which ethical alignment can be measured.

If an organization values transparency, changing their data-handling policy without notifying anyone means it is not acting in alignment with its values. A slightly more difficult example is how to honor the value of transparency in the event of an unexpected security breach. Should a responsible organization be completely transparent and notify everyone, should it be transparent just to the individuals whose data was breached, or should it extend that transparency to those organizations who would be affected down the data exhaust trail? How far does the value of transparency extend?

Imagine an opportunity to add a new product feature based on the correlation of two distinct data sets that allows more finely grained customer segmentation. But it comes at the cost of combing data sets from two different companies with two different policies about how their customer data can be used. It can be difficult to see how to maintain alignment across a range of multiorganizational values while simultaneously benefiting from that innovation. In some cases, those values will not conflict. In other cases, they may. Even identifying when they will and when they won’t can be a full-time job—let alone determining an appropriate course of action.

Value Personas can help parse out the conflicts between what you value and how you should act based on those values. They provide a mechanism for developing a common vocabulary, based on and informed by your own personal moral codes and aimed toward developing a set of common, shared values, which help reduce organizational barriers to productivity and encourage collaboration and innovation.

Some Value Personas may live essentially intact and unchanged for long periods. Others may evolve regularly based on changes in market conditions, new technologies, legislation, prevailing common practices, or evolutions in your business model. The dynamics of the conditions around which business decisions are made are highly variable and subject to influences that are often difficult to anticipate. Value Personas reduce the need to anticipate every possible outcome by treating them as worksheets capable of being used, revised, updated, and discarded as needed in response to those changes.

Technologists work constantly to evolve the abilities of big data. Social norms and legislation are slower to evolve. Competitive market forces, depending on your industry, can change at many different rates, from instantly to quarterly or yearly. There is no reason to expect that your ability to maintain alignment between your values and your actions can be wholly articulated fully in advance of all business conditions. Indeed, one of the benefits of the innovation opportunities big data provides is that it allows organizations to rapidly adjust to these market and competitive forces.

The ability to align values with actions allows organizations to create a common and shared sense of purpose and action around any given business initiative. As previously mentioned, turning the question of “should we do this” into “how can we do this” unleashes more collaborative thinking and work.

Value Personas, as a tool for developing this capability, are inherently scalable. Full, multiday workshops can provide ample time for organizations to develop a mature realization of their values and articulate suggested actions at various ethical decision points. However, these methods and tools works equally well in ad hoc hallway or working meeting conversations where ethical questions suddenly arise and ethical discussions begin.

Ideally, your organization has a core set of values to provide a starting point for these less formal use cases, but even in the face of disagreement about foundational values, Value Personas can give people a tool to start productive conversations.

Those conversations become productive when they’re made transparent and explicit. Value Personas can help as a tool, but the goal is not a nicely filled out worksheet. The goal is a clear and distinct plan of action, taking into account each individual role involved, and articulating exactly what each person is going to do, in what order, and what the intended outcomes or goals are for each action.

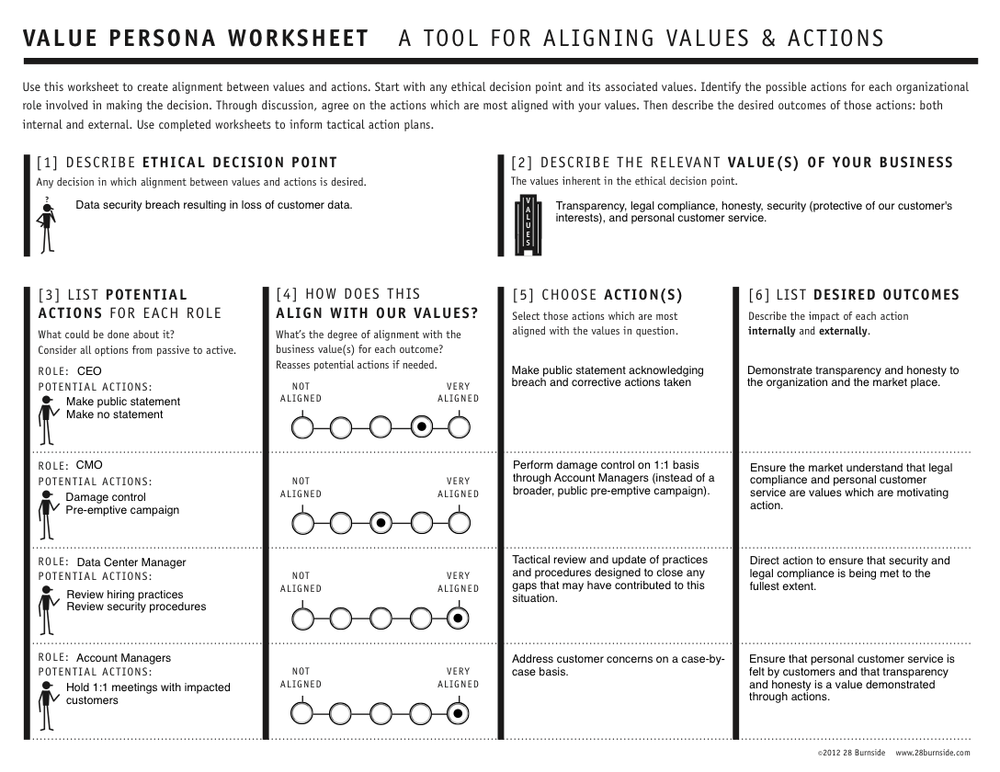

Consider the fictional company Global Data Management, a B2B data-handling and transaction processing company that explicitly values transparency in their data-handling practices. They publicly publish that position, actively share detailed information about their business operations, and frequently update their business strategy based on direct feedback from their customers. They share this information via many different communication channels, including: Twitter, their online customer community, blog posts, regular press releases, and their annual report. They have become very good at communicating with their customers. They have solid, long-term relationships with a large percentage of their customer base, and that base is growing in low double-digit percentages each quarter.

Global Data Management uses big-data technology to provide the majority of the products and services it offers. They run a Hadoop cluster of nearly 100 machines, process near real-time analytics reporting with Pentaho, and are experimenting with ways to enhance their customers’ ability to analyze their own datasets using R for statistical analysis and graphics. Their combined customer data sets exceed 100 terabytes and are growing daily.

Further, they are especially excited about a powerful new opportunity their data scientists have uncovered that would integrate some of the data in their customers’ databases with other customer data to enhance and expand the value of the services they offer for everyone.

They are aware, however, that performing such correlations must be done in a highly secure environment, and a rigorous test plan is designed and implemented. During the process of testing this new cross-correlated customer data set innovation, a security breach occurs. Global Data Management is devastated. A disgruntled employee, who had legitimate access to the data, walked out of the data center with a hard drive onto which he had copied tens of thousands of records of Global Data Management’s customers’ personal banking and financial transaction histories of their customers.

Now Global Data Management is faced with not just legal but also ethical questions. Their legal obligation may be to their customers only, but do their ethical obligations extend beyond those legal requirements? This scenario of unintended consequences generates a specific values-actions alignment question about the extent of notification required.

That is, does their value of transparency extend to their customers’ customers?

The ethical decision point can be framed in several different ways:

Do they tell just their customers, or do they have an obligation to tell their customers’ customers, too?

How far do they extend their value of transparency?

Does transparency mean “anyone who might be affected,” or does it just mean “those who are directly affected by our actions?”

There are likely to be several organizational roles involved in this ethical inquiry. Examples may include the CEO or COO, a representative from human resources, the data center manager, the manager of the disgruntled employee in question, and perhaps a representative from legal. These individuals bring both their own personal moral codes and their professional expertise to the inquiry.

This fictional example of a Value Persona shows the results of a productive discussion about how to align various proposed actions with Global Data Management’s value of transparency.

Used in this way, a Value Persona creates a common vision for guiding organizational practice that aligns with organizational principle.

Value Personas are a tool for implementing strategic decisions in a business practice. They express a clear statement of how a set of shared values is to be realized in the execution of business operations. They are most useful when shared throughout the organization and when everyone understands how, when, and where to apply them.

One of the best mechanisms for communicating those statements is derived from visual thinking exercises, which can result in many different formats and outcomes. One popular artifact is a detailed “usage map,” which is a visual representation of value-action gaps and the tactical steps that will be taken to close them. Usage maps can be highly engaging and visually depict a course of action that is easily shared across an organization to help facilitate common understanding.

When organizational practices and processes (actions) are aligned to support a comprehensive and explicit statement of principles (values), the benefits are many.

Employees, partners, owners, and so forth can collect their wages and profits in good conscience. Organizations can expect to enjoy better press coverage, better relations with customers and other generators of personal data, and quite likely increased revenues as individuals and organizations that previously avoided doing business together due to concerns with its handling of data come to view it as an organization that handles personal data in a responsible manner.

This doesn’t mean that all problems will disappear: disagreements over values can be heated and difficult to resolve. Individual moral codes are hard-won through life experience and they can be a challenge to evolve. But significant benefit can be realized from widely communicating Value Personas and the action plans they inform across an organization to help align operations and values in a consistent and coherent way.

Big data is one of, if not the, most influential technological advancement in our lifetime. The forcing function big data exerts on our individual and collective lives extends, and will continue to expand, into ever more personal and broadly influential aspects of society, politics, business, education, healthcare, and undoubtedly new areas we haven’t even thought of yet.

Businesses using big data now have to make strategic choices about how to share their innovations and balance them against the risk of exposing too much of their unique value proposition, thereby opening them up to competitive forces in their markets. The judicial system, from the Supreme Court on down, is now actively making legal judgments about everything from consumer protection and how big data is influencing personal privacy, to Constitutional issues ranging from First Amendment protections of free speech to Fourth Amendment rights against unreasonable search and seizure.

Politicians and governmental leaders from US Presidential candidates to the entire long-standing government of Hosni Mubarak in Egypt have experienced the power and influence of the ability of great masses of people, with a set of shared and common values and purpose, to change the course of history using simple tools such as social networks and Twitter.

Today, examples of social change and communication are available everywhere. Greenpeace has dozens of Twitter accounts organized by country and almost a half-million followers on one global account. Actor Ashton Kutcher can reach over 10 million people instantly. The American Red Cross has over 700 thousand followers. One has to wonder what Martin Luther King, Jr. would have done with a Twitter account. Or how the Civil War would have been changed in a world with blogs and real-time search. The telegraph was instrumental enough in how wartime communication took place; what if Lincoln or Churchill and Roosevelt had instant messaging? The Occupy movement has benefited enormously from being able to coordinate action and communicate its message on the backs of big-data systems. And, at both ends of the spectrum, imagine a data breach at Facebook: what would Hitler have done with that information? How would Mahatma Gandhi have utilized that kind of information about so many people?

And because of the sheer velocity, volume, and variety of big data, as it evolves, it is introducing ethical challenges in places and ways we’ve never encountered before. To meet those challenges in those new and unexpected ways, we simply must learn to engage in explicit ethical discussion in new and unexpected environments—not only to protect ourselves from the risk of unintended consequences, but because there are legitimate and immediate benefits.

The evolution of what it means to have an identity, both on and offline, raises deeply important questions for the future. If identity is prismatic, as Chris Poole suggests, do each of the aspects of our identity have equal rights? Are we to be allowed to change different aspects equally? Similar ethical questions exist around privacy. For an in-depth look at these questions, see Privacy and Big Data by Terence Craig and Mary E. Ludloff (O’Reilly).

Similarly, what it means to actually own something is changing. Do we own our personal data? If so, how do property rights extend (or not) to the use of personal data in exchange for products and services? What will be considered a fair and accurate judgment of an individual’s reputation in the future? Is an individual’s complete history of actions and behaviors on the Internet useful in making hiring decisions? There are certainly some companies who think so and will provide you with that information in exchange for a fee.

But even in the face of all these questions, the opportunity to extract value while reducing the risks is too tempting to ignore. Longitudinal studies in education hold the promise of helping us learn how to teach more effectively. Healthcare is running at mach speed to understand diseases and the human genome, and to improve doctor and hospital performance. Explicit ethical inquiry makes it easier to honor emerging and evolving legislation. As the law changes, understanding individual and organizational values (and how they relate to each other) and the actions they motivate will decrease the amount of time it takes to figure out how to be in compliance.

The alignment of common values and actions serves to increase the pace of innovation and make working teams incredibly more productive and efficient. Internal and external alignment deepens brand engagement with customers and generates loyalty and higher rates of satisfaction.

And so this book advocates not only learning how to engage in explicit ethical inquiry, but also suggests several tools and approaches for doing so. A practice of engaging in ethical dialog contributes to a much stronger ability to maintain a balance between the risk of unintended consequences and the benefits of innovation. We hope that those tools and approaches are helpful in your efforts to develop, engage in, and benefit from explicit ethical inquiry.

[6] As mentioned, it has recently been noted to that reading all the EULA you encounter would take an entire month every year (http://www.techdirt.com/articles/20120420/10560418585/to-read-all-privacy-policies-you-encounter-youd-need-to-take-month-off-work-each-year.shtml). The full study is here: http://lorrie.cranor.org/pubs/readingPolicyCost-authorDraft.pdf.