Friends of the 606: Building a Coalition to Build the Park

The 606 is currently the longest elevated greenway in the United States, a nearly three-mile long (12 acre), linear urban park. It is slightly more than 30 feet wide for most of its length, rising approximately 15 feet above the street level. The 606 includes the former Bloomingdale Line, an elevated railroad right-of-way on Chicago’s northwest side comprised of reinforced concrete retaining walls, soil, and 37 bridges where it crosses other roads. The greenway cuts across dense residential neighborhoods (home to almost 250,000 residents), a light manufacturing district, major commercial streets, a rapid transit line, an eight-lane interstate highway, and a river.

The 606 runs through four different Chicago wards: the First, the 26th, the 32nd, and the 35th (www.bloomingdale606.org). The First Ward contains parts of Wicker Park and Humboldt Park and is primarily Hispanic. The 26th Ward also runs through Humboldt Park and is also primarily Hispanic. The 32nd Ward contains the 606-adjacent neighborhoods of Bucktown and Wicker Park, and is generally whiter and more affluent than the other wards. The 35th Ward contains parts of Logan Square and Humboldt Park and is more socioeconomically and demographically mixed than the other wards. Figure 3.1 shows the 606 relative to the Greater Chicago area.

Figure 3.1 Bloomingdale trail or 606, Chicago

Source:606.org

The Friends of the 606, formerly known as the Friends of the Bloomingdale Trail (FBT), have been working on this project for over 15 years. They raised money from private donors and the federal government to complete the first phase of construction, which involved opening the entire 606 at a usable but low level of finish. With the dedicated help of the Trust for Public Land (TPL), the FBT is in the process of raising private money for the additional, decorative phase of construction. It has built a coalition of supporters, combining socially distinct neighboring communities, government agencies, private donors, nonprofits, other interested local organizational actors, and so on. Their neighborhood support comes primarily from the communities of Logan Square, Bucktown, and Wicker Park. There has been little involvement by Humboldt Park community members, neither actively supporting it nor organizing against it.

The FBT and its supporters can be considered successful because they were able to develop and support several key themes around the 606 and development efforts, over time and across audiences. First, the FBT focused on emphasizing how users would access the 606 and what they would do once on the 606. The FBT also developed and maintained themes around how the 606 would be operated once open, and how the 606 would fit in with the disparate neighborhoods it connected. The presence of key themes and the consistency with which they are treated can be seen as a measure of FBT’s ability to reconcile the competing logics they are drawing upon and frame their solution—the 606—as the correct one for the identified problem.

Brief History of Civic Action

In the early 2000s, as part of the City of Chicago’s Open Space plan (City of Chicago et al. 2004; Stephen 2012), the city identified potential pockets of green space that could be developed in different city neighborhoods. In 2002, the City of Chicago and the Chicago Park District, an independent local governmental entity, began developing the Logan Square Open Space Plan. The plan listed 11 locations in the Logan Square area that if developed, would address the current deficiency in Logan Square’s open park space acreage. That list included plans to convert the nearly three-mile long Bloomingdale Line into an elevated, multiuse, linear park and trail (Logan Square Open Space Plan Task Force 2004); the project eventually was named the 606, in honor of Chicago’s area code. FBT was initially a group of Logan Square-based bike enthusiasts who began discussing the 606 and the prospect of developing it, as a result of attending community meetings. This group realized they needed to organize formally, to show support for development, and to backup this support with community-based planning.

In October 2002, as part of their work on the Open Space Plan, six members of the task force formed the formal entity then known as the FBT and now called The Friends of the 606 (Stephen 2012). Ben Helphand, the current President of FBT, was among them. These six individuals had backgrounds ranging from community organizing to operating small restaurants to community garden preservation (www.606.org). This group of six soon became a group of 20, and FBT was enthusiastically advocating for the conversion of the 606 embankment into an elevated, multiuse, linear park. The initial group of 20 people has swelled to over 1,000. Through organizing community events, FBT has strived to be the community’s introduction to and voice for the vision of the 606. As Ben Helphand, FBT’s president comments, our initial goals were, you know, “Preserve the right-of-way.” What we found pretty quickly is pretty much everybody liked this idea, and nobody was actively against it. We visited all the community groups, made presentations, got official endorsements from all the local elected officials. So, very quickly [a] need to circle the wagons was irrelevant. And what we turned into is really more of a champion of this, keeping the wheels greased, keeping people excited about it, holding events, keeping the idea in the forefront of people’s minds and imagination. And that has been our main focus over the years (Helphand 2009).

FBT has focused on building a coalition of partners to support 606’s development. The leadership at FBT reached out to the national advocacy group Rails-to-Trails Conservancy (RTC) for help in the initial stages of advocacy, including asking RTC to help spread the word about the 606 to its membership and encourage them to attend public meetings (Oberg 2011; Helphand 2011). The Trust for Public Land (TPL), a national land conservation organization,1 has taken a public leadership role in spearheading private fundraising, overall project development, and management of the 606.

TPL has worked on the 606 project since 2006, when the City of Chicago and the Friends of the 606 asked for assistance with land acquisition, community participation, and design competitions.2 TPL and FBT created the 606 Collaborative as a framework for public and private sector partnerships to do the project. The collaborative has engaged nearly 25 organizations and agency departments; those most heavily involved are the Chicago Department of Transportation (CDOT), responsible for applying for Federal funding, the Chicago Department of Zoning and Land Use Planning (CZLUP), responsible for permitting and land acquisition for access parks, and the Chicago Park District (CPD), with ultimate operational and maintenance responsibility.3

In 2007, the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning designated CDOT for federal transportation funding for design and engineering work. In November 2008, the City of Chicago released a request for proposals to address the engineering analyses required in the preliminary design of the 606 (TPL, Winter 2008–2009). In June 2010, CPD’s Board of Commissioners approved a challenge grant of up to 450,000 dollars to TPL, to coordinate the 606 Civic Engagement and Stewardship Project. Under the terms of the challenge grant, TPL expanded participation to additional community and civic organizations that expressed an interest in playing a role in the 606’s development.

Most of the project’s Phase One budget was covered by federal anti-congestion and air-quality funding federal funds (Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning 2011), and part of TPL’s challenge grant involved a commitment to raise the remaining 20 percent of needed funds. But, even as the project was moving forward and design for Phase One had been awarded, there was not a clear sense of when the 606 would actually open (Vance 2009), until Mayor Rahm Emanuel was elected in 2011, and announced that the 606 would open by the end of his first term (Helphand 2011; White 2011). The first phase, which involved opening the entire park or elevated trail at a minimal finish level, opened in June 2015. Phase Two is underway, and there is not yet a definitive completion estimate.

Discourse Themes as Mechanism for Reconciling Competing Logics

The discourse is divided almost equally among the three dimensions of institutional work the 606 entrepreneurs have undertaken in order to make their project a reality, consistent in tone, and mostly neutral or positive. The only exception is the gentrification subtheme within the neighborhood theme, which is neutral or negative in tone. Table 3.1 summarizes the dominant themes within every dimension along with a note on the tone and consistency within each theme.

Table 3.1 Summary of themes within institutional dimensions in the 606 discourse

|

Dimension of institutional work |

Theme |

Tone of theme in discourse |

Consistent use of theme in articles, interviews, discussions, and presentations |

|

Envisioning |

Access or usability |

Neutral or positive |

Yes |

|

Envisioning |

Aesthetic |

Positive |

Yes |

|

Creating |

Development |

Neutral |

Yes |

|

Creating |

FBT capacity |

Neutral |

Yes |

|

Legitimating |

Green |

Positive |

Yes |

|

Legitimating |

High Line |

Neutral or Positive |

Yes |

|

Legitimating |

History |

Positive |

Yes |

|

Legitimating |

Narrative |

Positive |

Yes |

|

Legitimating |

Neighborhood |

Subtheme gentrification: neutral or negative Subtheme of safety-neutral or positive |

Consistent within each subtheme, but split overall |

In addition to being tonally consistent, the discourse is relatively balanced over time, with each dimension accounting for approximately one-third of the discourse. Access or usability dominated the envisioning dimension. The development process dominated the creating dimension. The theme of neighborhood dominated the legitimating dimension. These three main themes together accounted for 73 percent of the coded discourse.

Envisioning Work

Access or usability comprised 27 percent of the overall discourse; most of the discourse around that theme is positive or neutral. The intersection of access and usability issues has come about because the 606 incorporates bicycles, requiring ramp-based access, and requiring complex kinds of development efforts to link the 606 and the ground. In addition, the entire 606 opened all at once, like the proposed Lowline, but unlike either the High Line Park in New York or the Rail Park in Philadelphia. Opening all at once affects both access and usability (Leopold 2011; Bornstein 2011; White 2011); all access points must be open (for ADA compliance reasons), as opposed to the High Line Park, which had initial access points designated for each section as it opened.

Figure 3.2 shows an image of a trail access point.

Figure 3.2 606, trail access point

Source:Victor Grigas/Wikimedia Commons/Bloomingdale Trail, the 606, Chicago 2015-35.jpg

Emphasizing how to access the space in the discourse around the 606 makes the project feel more tangible. If stakeholders are debating where to develop access parks, or how the access ramps should look, they have already bought in to the project happening. As with FHL in New York, this changes the entire discussion to one focused on “getting it done,” as opposed to “should we do it?”

Even in the beginning stages of the project, it was clear that being able to experience the 606 and park at multiple levels was part of the appeal (Pietrusiak 2004; Dickhut 2011). Andrew Vesselinovitch, park’s Director, Chicago Office, TPL, explained that “because this is elevated, unlike many parks, you need to be very conscious of where the entrance and exit points are going to be……there was a discussion of where these access points were gonna be. Many of them are existing parks” (Helphand and Vesselinovitch 2009). This inclusion of the ground-level parks as access points was partly driven by the fact that the ground-level parks could open before the elevated portion of the 606 (Helphand 2011; White 2011). In 2007 to 2008, once it became clear that the park was moving forward, and the city was intent on developing it as a park, discussions began to focus on how to access the park, as it was nearly 15 feet off the ground. As David Leopold, Chicago DOT Project Manager described,

Our space is certainly similar [to the High Line] in terms of the idea of a lifted landscape. I think it’s similar in terms of we use the old infrastructure for a new purpose that it wasn’t originally intended for, but that these can have lives beyond the original intention. I think what’s different, of course, is that ours is a multi-use path as opposed to more of a strolling environment…. certainly intended to be welcoming to bikes…[and] is a raised embankment; has a little more earth to it, with bridges crossing over various streets through the neighborhood and things like that. So …. I think it allows us to do different things that maybe the High Line would not have (Leopold 2011).

The team had to determine how the access points would be designed, and how the 606 would balance competing, possibly conflicting park uses. “There is a tension between is this a multi-use path that connects a group of parks? Or is it a park in itself?” (Bornstein 2011). The design team reached out to bring community members into the design process. They wanted to understand what members wanted the park and 606 to look like (even if not everything on the wish list was achievable). Part of this process involved a Fall 2011 charrette, where community members actively participated in discussions around the aesthetics of the 606 (Galef 2009; Vance 2011). It became clear from those discussions that community members wanted a park and multiuse trail, but feared conflict between people walking and biking (Dries 2012; Hauser 2017). They also found that that community members wanted many access points (October 2011 charrette meetings, Vance 2011).

As a result of the 606’s narrow width, and based on community feedback, the design team decided to plan the elevated trail activities to serve individuals and small groups, instead of accommodating big gatherings. The ground-level parks are designed to accommodate neighborhood uses such as playgrounds, basketball courts, skate parks, and access parks; this set of uses can enhance the relationship between the ground level and the elevated park (October 2011 charrette meetings, Vance 2011; Vance 2012).

Traditional park amenities, like large open spaces for large groups, ball fields, and play areas, are all things that would be hard to accommodate on a narrow trail, but can be accommodated in adjacent facilities. Many of the surrounding neighborhoods are communities of color; these kinds of common recreations draw people of color in particular to parks (Bliss 2017). Note that this positioning is in contrast to that taken by the Friends of the High Line (FHL) and supporters, who focused on the High Line as a beautiful open space as opposed to a park.

As bicyclists and pedestrians would both use the 606, questions surfaced about how to separate the two uses safely, and how the park would work for different segments of the neighborhood—who is it designed for? (Helphand and Vesselinovitch 2009; Hauser 2017). Notably, there are still questions about whether the space really works for both cyclists and pedestrians, with regular reports of pedestrians being struck by cyclists, in some cases causing serious injury (Hauser 2017). There were and still are feelings by some members of the community that the 606 has been designed for the cyclist community, not the Hispanic or minority community. The Hispanic or minority community has members who might use the 606 as a safe walk to school, and so on—the cycling community, far less so (October 2011 charrette meetings, Vance 2011; Gomez-Feliciano 2011; Echevarria 2011).

I …. acknowledge ADA access, and …. there would be access at least every half mile with a ramp so that it’s accessible to everyone. … I have been suggesting that they put in place staircases in between every half mile….. And I think that is also going to help get more of the local people up—says Lucy Gomez-Feliciano, Health Issues Coordinator, Logan Square Neighborhood Association.

I think it has a potential to function as a park but that potential can only be realized to the degree that people see it as something that they own, something that’s part of their community, their neighborhood. If people don’t—you know if the residents don’t use it then it will be relegated to merely a bike trail, says Raul Echevarria, Puerto Rican Cultural Center.

The usability discussion and programming were largely driven by the sources of funding. The choice of discourse themes is always constrained to some degree by the physical object: its location, its visual characteristics. As the first phase of the project was funded largely through Federal Congestion Mitigation or Air Quality (CMAQ) transportation funds, the 606 must accommodate cyclists as well as pedestrians (Leopold 2011; Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning 2011). Frankly, the cycling part of the 606 does explain, at least in part, the focus on access and usability themes in the envisioning discourse. “It was very helpful explaining to the public that it would have to accommodate bikes as well as people walking to the bus stop,” Vesselinovitch said. “People understood that you can either allow bicycles or try to find [nearly] $40 million somewhere else” (Brake 2012). As a result of the programming requirements, there is a shared bike or pedestrian path running the length of the elevated part of the 606 as well as shorter, additional pedestrian-only segments along the wider portions. This programming requirement, plus the 606’s narrow width, limits the amount and kind of plantings that the space can handle.

At a March 2012 public meeting, the design team unveiled a framework plan that responded to the October 2011 charrette. An important objective of this framework plan was to balance park aspirations. As Joseph Bornstein, from CPD, described it,

some people think the 606 itself should be you know, like the High Line in New York. That the 606 itself will be decked out in the amazing every single inch of the way. Whereas others think, you know, there are parts where the 606 is a little wider where you can do some really cool things but for the most part it’s going to be a 606, an elevated 606. And the fun parts will be pretty much just the parks along the way (Bornstein 2011).

A concession made to the pedestrians was the decision to limit cycling to no greater than 20 MPH (Chicago-pipeline.com, Vance 2012). It is not clear if this concession helps pedestrians (Hauser 2017), given the narrow space, and multiple, competing uses. A second concession, made to both bikers and walkers, was to pull back from plans for a “wheel-friendly event plaza” (Greenfield 2017) for biking and skating at an access park at the east end of the 606, in the Bucktown neighborhood. The official reason for leaving the existing area un-programmed is that nearby residents find the area lovely (Greenfield 2017), and it is located near a playground and dog-friendly area on the 606’s north side. But, another motivation for leaving the area un-programmed appears to be the neighbors’ negative perceptions of the skateboarders (mostly teenagers) who would have used the facility. The residents have not been completely silent on this issue. “Skateboarders bring in a different element to [The] 606 than bicyclists, walkers and joggers” (Hauser 2017), not one residents necessarily want to see. Figure 3.3 shows an unprogrammed access park.

Figure 3.3 Un-programmed access park

Source: Google Street View.

Creating Dimension-Development or Cost

The discourse in this dimension has to explain why FBT, as the community voice for the 606, makes sense as a solution to the problem FBT has identified and reframed. The dominant theme in this dimension was the overall process of 606 development and associated costs. Most of the discourse is positive or neutral. Negative messages within this theme start off at about the same level as neutral themes, but quickly become less prevalent in the discourse, starting in 2005 to 2006. Negative themes became stronger again when the project was under development for several years without much momentum.

The discourse and dialog around development of the 606 fell into two broad subthemes, due to the extended nature of the 606’s development process. On the neutral or negative side, journalists and bloggers expressed skepticism over whether the project would actually happen, despite the city’s support. On the positive side, the process enabled the Friends of the 606 to define and refine their role, and allowed city government agencies, TPL, and FBT to explain, consistently, the roles of different network partners in the 606’s development coalition along with framing the cost as an investment in the area.

TPL began highlighting the role of the FBT while discussing the 606’s possibilities in its quarterly newsletters (TPL, Winter 2006; Summer 2007; Winter 2007–2008), with particular focus on the access parks needed to link the 606 to the ground. Ground-level access parks were a critical part of the 606, and because they were actually developable ahead of the 606 itself, those parks became the TPL’s main focus (TPL.org, White 2011; Helphand 2011; Oberg 2011; Ciabotti 2011) Both FBT and TPL felt that opening the parks would increase awareness of the project and provide much-needed green space for the four communities surrounding the 606. Using its own money sources as well as fundraising, TPL helped the City of Chicago to acquire four city lots needed to access the 606 (activelivingbydesign.org 2007), though the city has ownership and maintenance responsibility. Their efforts were reported in the local papers, along with their investment in the 606. “So far, the Trust has spent $2 million buying properties to be used for access to the elevated 606” (Dominick 2008, also see TPL Winter 2007–2008). TPL and FBT also highlighted private, corporate donors involved in supporting the new parks.

Foundations giving money to BT: Alcoa, Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC), New Communities Program, MetLife, Oberweiler Foundation, Dr. Scholl, Related Midwest, Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation, and Searle Funds at the Chicago Community Trust. (TPL, Winter-2007–2008)

The contract for Phase One development was awarded in 2009 to a multicompany construction and development group led by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates (Greenfield 2010; Vance 2011). While the design team began to develop detailed construction drawings, estimates for the park’s cost began to increase. Initial estimates put the 606 at 20 million dollars (Pietrusiak 2004). By 2011, estimates had quadrupled (tpl.org 2010; Greenfield 2011). Some of this increase can be attributed to better information about the kind of work required to convert the structure to a park, including completed engineering studies, and thus the condition (and any repair work required) of all 37 bridges along the 606 (White 2011; Bornstein 2011). Some of it can be attributed to increasing the scope of work, including plantings. Some of it can be attributed to developing the access parks.

Of the total amount needed for construction, 46 million dollars was dedicated to Phase One and the remainder to Phase Two (Kamin 2011). Phase One, or Basic (Dries 2012), opened the complete 606 system and access points to the public. Phase Two focuses on building and sprucing up existing parks next to the 606, including walkways, architectural flourishes, and public art, as well as providing for long-term maintenance (Donovan 2012). These estimates do not include at least two million dollars in land acquisition costs (activelivingbydesign.org 2007).

City agencies, FBT, and TPL all had to explain the project’s increasing price tag and delays in building despite the apparent support. There were concerns that Chicago, as cash-strapped as it was, would have to shoulder most of the construction cost (Kamin 2011). In response, the team had to explain that Phase One was funded largely through Federal CMAQ transportation funds, so the Federal government provided much of the funds, and that money just takes longer to get (Pietrusiak 2004; Fagel 2009; Bornstein 2011; Leopold 2011; Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning 2011). Part of the delay in construction was also due to the fallout from the 2008 economic slowdown, projects just taking longer to be approved, and new administrations in both Washington, DC and the City of Chicago. As Joseph Bornstein of the Chicago Park District explained:

To get to why can’t you just start building it now and why does it need to take that long? I’ve always found—and please do not let this come across as condescending but—people who don’t work in industries where you build things never understand how difficult it is to get all your approvals and do all your steering and as well to line up all the necessary funding for something. (Bornstein 2011)

City officials consistently said not everything people want aesthetically in the 606 will be there, due to funding limitations and the pressure to open the 606 all at once. Chris Gent, the Park Liaison from the Cultural Affairs Department said, “It’s a very different and unique space but not everything can be accommodated” (Gent 2011). Kathy Dickhut, from the Department of Zoning and Land Use Planning, concurred, saying that

I’m sure we can get something open from end to end that’s safe, that’s usable, that’s interesting…. Will it include everything everybody’s thought about and everybody wants? Probably not, but that doesn’t mean that over time things can’t be sort of embellished. (Dickhut 2011)

Some of the demands for certain items or activities that could not be accommodated came about as a result of the community-visioning sessions FBT organized throughout the long development process. There are many members of the communities affected by the 606 who faithfully came to and participated in community-visioning sessions, over a period of years, and kept the faith, so to speak. As a result, they developed a belief that expressing a particular vision over years and years, even without funding and clear plans for the park, somehow made that vision more likely to be implemented. FBT wanted community members to buy in all along, but sometimes individuals get bought-in to what they have expressed, and for budgetary or other reasons, it is not possible to accommodate those demands. That can leave community members feeling cheated or affect their motivation. There is also an aesthetic challenge, given the high level of finishes of the High Line, a sister project of the 606, which notably opened in complete phases two to three years apart.

Focusing on the development process, and particularly FBT’s role in keeping the community believing the 606 would happen, reassures community members and potential donors that the advocacy group involved, and advocacy, in general, can actually make the project happen. FBT also developed and touted the consistent theme that minimal City of Chicago taxpayer money was involved. Making sure community members know that most of the money required for Phase One came (theoretically) from Federal coffers worked to dampen project opposition.

Legitimating Dimension: Neighborhood

The final part of the discourse around the 606 involved connecting the supporting rationales of the project to the neighborhood. Notably, there was not very much discussion about the High Line, even though that was the only similar project in the United States open during planning. From talking with the individuals involved, the FBT coalition was afraid that explicitly using the High Line’s words and phrases would have made their project appear elitist. Within the overall theme of the neighborhood, two different subthemes emerged. The first, by far the most dominant, involves issues of safety and security for neighborhood residents. The second involves the effects the 606 will have on gentrification, especially in the Western communities, and affecting long-time residents. This concern about gentrification appears in all four cases profiled.

Legitimating or Neighborhood Safety and Security

There are no bathrooms on the 606 or any of the access parks (3-8-12 Public meeting, 606.org), although there are plans to add public bathrooms to the McCormick YMCA, which provides an access point to the 606 (Bloom and Hauser 2017). A lack of bathrooms in the design limits opportunities for homeless people to linger on the 606, limits opportunities for general sexual predation or whatever,4 and limits use of the 606 by nonresidents. So, FBT and its supporters sent a clear message that they were encouraging neighborhood 606 use. This is a clear contrast to the High Line project in New York, where “the High Line is one of a kind, but it wasn’t designed to have accommodating neighborhood residents as one of its guiding principles” (Stone 2012). It remains to be seen what happens once the bathrooms actually open, sometime in 2018.

The neighborhood safety theme is where there was the most disagreement in the discourse. City officials and supporters of the project all felt strongly that residents would be much safer once the 606 was converted for park use. One of the ways to manage community members’ insecurity is to encourage as much use as possible and have many people up there (Gent 2011; Hauser 2017). Members of FBT have also emphasized that the 606 is close to 12 elementary schools; so the immediate community can use the 606 as a Safe Walk to School. FBT and its supporters see increasing the diversity of users as increasing safety overall. This sentiment is very much in line with Jane Jacobs’ concept of eyes on the street (Jacobs 1961); the 606, like a street, is safer when more people are on it. TPL estimates over 1.8 million people will use the 606 in 2017 (Hauser 2017).

At a 2012 public meeting, Glenn Brettner from the United Block Club of West Humboldt Park and a member of the Humboldt Park Advisory Council, also argued that, “I do not see … that this will be less safe. There will be more people and more lighting which tends to lessen not increase crime” (Coorens 2012, 3-8-12 Public meeting). And, FBT President, Ben Helphand, insists that “the only long-term solution to crime is the 606 itself; anything we can do to hasten its creation will bring permanent safety to that corridor” (Helphand 2011). This position has been supported by the police, who describe crime on the 606 as really modest, (Hauser 2017), and urge continued use. “The safest thing we can do as a community is use it, stay on it. The more people on it, the better” (Hauser 2017).

Residents expressed concerns that people would be able to look right in their windows and be using the 606 until late at night,5 acknowledging the tension between addressing the desire for privacy and also having eyes on the 606. While making the 606 into a park patrolled by police would make it safer overall, it also brings more people up onto the 606. In theory, this would mean more people who could look right into their homes, including the police.

Overall, crime has gone down since the 606 opened. In 2017, three researchers published a study comparing city crime statistics in neighborhoods closest to the 606 with similar socioeconomic neighborhoods elsewhere in Chicago. They compared crime statistics from 2011 to 2015, and found that all kinds of crimes fell faster in 606-adjacent neighborhoods than elsewhere (Bloom 2017). But, over the 16 months, including all of 2016 and the first seven months of 2017, there were 26 crimes reported on the trail, itself (Hauser 2017; Hauser 2017; Hauser 2017); at least a quarter of the crimes happened after 10:30 p.m., near or after the park’s 11 p.m. closing time. Another quarter occurred between midnight and noon. The remaining half were between noon and 10:30 p.m. Those crimes feel like a lot, even though:

When asked by a resident if he thinks the crime level is high or low, Sgt. Adam Henkels (CPD) responded: “really modest.” Capt. Thomas Shouse (CPD) added that while “even one [crime is too many],” given the fact the [elevated part of the 606] is “basically the size of a beat but stretched out and up in the air, it’s fairly low.” (Hauser 2017)

Legitimating or Neighborhood Gentrification

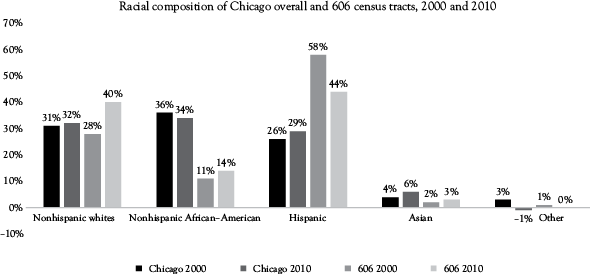

Both the Humboldt Park and Logan Square areas have already seen demographic shifts, bringing more affluent whites into their communities and displacing long-time, primarily Hispanic, residents. In the past 10 years, the area around the 606 has become more White and less Hispanic, while the group of census tracts as a whole has seen almost no change in overall population. As Figure 3.4 shows, in 2000, the overwhelming majority of people living in census tracts near the 606 were Hispanic, but this number dropped substantially over the following decade.6

Figure 3.4 606-adjacent census tracts and Chicago total population, 2010 and 2000, by race

Source:American Community Survey, City of Chicago GIS.

Median household annual income for these 20 census tracts is approximately 52,350 dollars, compared with 46,781 dollars for Chicago overall. This income premium is approximately 12 percent, and household income has increased an average of 3.6 percent annually since 2000, when it was slightly over 36,000 dollars for the 606-adjacent census tracts (www.census.gov). In addition, housing prices in the Humboldt Park, Logan Square, and Wicker Park or Bucktown neighborhoods increased by 21.5, 13.5, and 9.2 percent, respectively, in the first year since the 606 opened (Institute for Housing Studies 2017), compared with 8 percent for the City of Chicago overall. More specifically, there has been a 50 percent surge in home prices since 2013, when construction on the project began. The most dramatic increases have hit the trail’s less affluent west end, in the Humboldt Park and Logan Square neighborhoods (Jacobs 2017).

The concerns of long-time area residents would seem to accurately reflect the changes in their neighborhoods and the people around them. In early 2017, two local Aldermen introduced legislation designed to slow down the pace of gentrification near the 606 through zoning changes or developer incentives or fines (Bloom and Hauser 2017). It may be too little too late—the 606 had been in the works for several years before it was completed and arguably the Aldermen should have anticipated the problems (Schulte 2017).

FBT has had mixed success in understanding the Humboldt Park and Logan Square communities, and in encouraging real participation. This has become more problematic as Logan Square has gentrified. Yes, a lot of planning has happened, yet the plan of outreach to said communities and the surrounding residents (houses, homeowners, organizations, block clubs, churches) right next to the 606 never really turned into resident support. As a result, project support has come primarily from the East and North sections of the 606, and there has been scattered support from other segments of the community. Former FBT Board Member and community activist Raul Echevarria said he thinks it is partly to do with how FBT members have been used to organizing the whiter, more affluent parts of the 606 community.

This is very much a Logan Square driven project and … they sort of have a way of working that is not—that was not really in line, in alignment with Humboldt Park….And so they struggled with it. [I had] some frustration just in maintaining that this is not working, using the same organizing [approach from Logan Square is] not gonna work in Humboldt Park. It’s not gonna be just—it can’t just be white male driven…. I mean they tried to make adjustments but it was just too much…it was just too much work you know to build beyond … their… way of working. (Echevarria 2011)

Further, Echevarria, and another Latinx former FBT Board Member (and community activist), Lucy Gomez-Feliciano, argued that FBT’s bilingual fliers were not enough to address the cultural differences between the communities. “They have to ask themselves why don’t people come to meetings?” (Echevarria 2011; Gomez-Feliciano 2011). Other examples of minority outreach include organized events underneath the 606’s viaducts, and active recruitment for the community visioning sessions and charrettes. Gomez-Feliciano pointed out that, if FBT members just sent “it [the notice of the charrette] out to their friends it would not include a lot of the brown population in that community. …So, you know, I reached out to people to make sure that the people attending those charrettes are diverse” (Gomez-Feliciano 2011). But, Echevarria challenged her efficacy in getting participation, arguing that:

I think the only way that it would just really work [with] the local park is just with me or someone like me were driving those components in Humboldt Park. And other folks on the board, ….there was a Latina on the board [Lucy Gomez-Feliciano] but she was from Logan Square, [and I] think that she was also for buying a Logan Square way of doing things. She would not—she was not that successful. (Echevarria 2011)

Echevarria and Gomez-Feliciano gave the impression that the Humboldt Park and Logan Square residents are not against the 606 in concept, but may be against how it has materialized. There is not an organic grouping of Humboldt Park and Logan Square residents who want to put their time and energy into the 606 (Echevarria 2011); tellingly, there is also not an interest in organizing opposition to the 606. It is possible that many members of this less-affluent community really do not have the time to invest on either side of the project. Interestingly, both Echevarria and Gomez-Feliciano left the FBT Board due to changing job responsibilities. Gomez-Feliciano has continued to do outreach for the project through local community group Logan Square Neighborhood Association (LSNA). Echevarria does not do 606 outreach in his role, as his responsibilities as the Executive Director of the Puerto Rican Cultural Center take up most of his time.

Promoting the idea that the 606 is for the neighborhood does not completely resonate with some communities nor does it alleviate their concerns. Frankly, it cannot do that, given that the neighborhoods on the 606’s Western side are changing. It is not entirely clear, here, which is the chicken and which is the egg. Is the park exacerbating existing demographic changes already going in Humboldt Park or Logan Square or would those changes happen anyway? Similar questions are being asked in New York, where gentrification has occurred around the High Line, and Lowline, as well as in Philadelphia. And, like in New York’s High Line (and the proposed Lowline), there are times when part or all of the park is closed for a private event. While little private money was used to fund Phase One, which opened the whole trail, private fundraising is needed for Phase Two, which is more aesthetic. The Park District’s involvement has also enabled them to close off parts of the 606 for fundraising dinners and special events (Hauser 2017). The event fees collected “help fund neighborhood park improvements and programs” (Tostado, via Hauser 2017). The closure of part (or all) of these parks for events again raises questions about who these parks are for, and the role of private money in public spaces.

Summary and Conclusions: What They Did Well and Less Well

FBT and its coalition of supporters raised enough to open the entire 606 Trail in Basic mode in June 2015. The choices they made along the way have resulted in a lovely, local, urban amenity very different in feel from New York’s High Line. Unlike the High Line, there are few places to sit and linger along the 606’s 2.7 miles. “The main focus is on movement… [since the ] structure is typically only 32 feet wide.” (White, quoted in Keegan 2015). That narrow width was a major design obstacle, and may become 606’s biggest challenge. It might be a great place to bike and run and a terrible place to stroll—or it might be the opposite. It will only be a success if people can figure out how to interact based on different modes, and speeds, of transport along the way (Keegan 2015). Some argue that the 606 falls short of the High Line, in that it is “not a project of citywide significance, nor a bona fide tourist attraction for the masses. It’s a neighborhood-serving rail-trail that is elevated above the streets with some nice features, like lighting, that you don’t see often.” (Greenfield 2015).

I disagree. The 606 may never be the tourist attraction the High Line is, and that is fine. The 606 draws people from many different parts of Chicago, and differs in three major ways from New York’s amenity. First, it’s nearly twice as long as the 1.45-mile Manhattan path. Second, unlike the High Line, you can bike on the Bloomingdale, and it provides direct access to 12 public and private schools, so it functions as a very useful transportation link and connector.

Finally, the 606 is more demographically democratic. The High Line runs through some of New York’s most expensive real estate, and at least during the times I have visited, the crowd seemed to be homogenous. The 606 does exactly what it is designed to do; it connects economically and ethnically diverse neighborhoods; in nice weather, you can see whole working-class families, including grandparents and little kids, out on the 606. That is a sight you probably would not come across in Chelsea. About 1.6 million people used the 606 in its first full year of operation, a number projected to increase 15 percent in 2017 (Hauser 2017).

Some Chicagoans have argued that the city spent too much money to make the 606 a world-class amenity, while a simple paved path might have had similar benefits, with less impact on gentrification (Greenfield 2015). Others argue that the trail had “a budget that was too low, and the unfinished metal for railings and security fences along The 606 gives the trail a prison yard vibe; a design choice due to funding limitations” (Renn 2015). But, the trail itself is still largely a work in progress.

During the buildup to opening, Friends of the 606 and its coalition of supporters gave nearly equal time to each dimension of institutional work through active investment in the discourse. Each of the three dimensions plays a necessary role in seeing the venture through. Success or failure of the 606 depends on the ability of the advocacy group and its coalition to focus and bring to life the imagination of its potential users (and donors).

FBT and its supporters chose to focus on the practical aspects of the park’s development. Ben Helphand argues that was purposeful, as “we want the Park to reflect that ‘Chicago is the City’ that Works” (Helphand 2011). That may be due to programming requirements and budget limitations, it may be post-hoc justification, or it may be an accurate reflection of the underlying attitude. That said, there is not a lot of discussion about the beauty or magic of the 606, as opposed to the discourse seen both in the High Line (discussed in Chapter 2) and the Rail Park (discussed in Chapter 4). Those elements are just less important in the discourse around the 606. The plan was always to get the 606 in functional shape as early as possible, and then raise money for more plantings and public art, plus recreational equipment for the access parks, as well as maintenance and programming. Of the 40 million dollars needed from private donations, 24 million dollars have been raised so far (Greenfield 2015).

In effect, FBT has treated the 606 and access parks as symbolic and physical opportunities to connect four neighborhoods: Humboldt Park, Logan Square, Bucktown, and Wicker Park. This strategy appears mostly to have worked in smoothing over racial or neighborhood-based tensions. That, itself, is an important achievement, given the different socioeconomic statuses of the four communities surrounding the park. Beth White of TPL has described the 606 and park combination as being a charm bracelet, with the parks dangling off the chain of the 606 (White 2011; Kamin 2011; Donovan 2012). Another way to think of it is that FBT has been able to use the 606 as the charm bracelet, and the communities as the charms, in its reconciliation of different, yet critical institutional logics.

1 TPL is the nation’s leader in creating parks and conserving land for people from the inner city to the wilderness. They are a national organization that is focused on urban public spaces in the form of city parks and playgrounds, urban gardens, and other green projects in and around cities, large and small.

2 TPL, in its capacity as owner’s representative for the Chicago Park District, is working with the Chicago Park District and two City departments: the Department of Transportation and the Department of Housing and Economic Development. Once the trail is complete, the Chicago Park District will assume ownership of the trail (tpl.org).

3 In a unique arrangement with the city of Chicago, TPL is actually corralling all the local nonprofits, city agencies, donors, and railroad companies involved. The organization, which usually functions simply as a land trust, is also becoming the agent that manages the park over the long term.

4 A popular anti-homeless prejudice.

5 Chicago parks close at 11 pm.

6For purposes of situating the park, I used 20 census tracts, all in Cook County that are adjacent to the 606. They are census tracts 2301, 2302, 2303, 2308, 2309, 2401, 2402, 2403, 2404, 2405, 2406, 2407, 2408, 2409, 2410, 2411, 2412, 2413, 2414, 2415, and 2416 (ACS 2005-2009, American Fact Finder (www.census.gov).