CHAPTER 9

Redo and Undo

This chapter describes two of the most important pieces of data in an Oracle database: redo and undo. Redo is the information Oracle records in online (and archived) redo log files in order to "replay" your transaction in the event of a failure. Undo is the information Oracle records in the undo segments in order to reverse, or roll back, your transaction.

In this chapter, we will discuss topics such as how redo and undo (rollback) are generated, and how they fit into transactions, recovery, and so on. We'll start off with a high-level overview of what undo and redo are and how they work together. We'll then drill down into each topic, covering each in more depth and discussing what you, the developer, need to know about them.

The chapter is slanted toward the developer perspective in that we will not cover issues that a DBA should be exclusively in charge of figuring out and tuning. For example, how to find the optimum setting for RECOVERY_PARALLELISM or the FAST_START_MTTR_TARGET parameters are not covered. Nevertheless, redo and undo are topics that bridge the DBA and developer roles. Both need a good, fundamental understanding of the purpose of redo and undo, how they work, and how to avoid potential issues with regard to their use. Knowledge of redo and undo will also help both DBAs and developers better understand how the database operates in general.

In this chapter, I will present the pseudo-code for these mechanisms in Oracle and a conceptual explanation of what actually takes place. Every internal detail of what files get updated with what bytes of data will not be covered. What actually takes place is a little more involved, but having a good understanding of the flow of how it works is valuable and will help you to understand the ramifications of your actions.

What Is Redo?

Redo log files are crucial to the Oracle database. These are the transaction logs for the database. Oracle maintains two types of redo log files: online and archived. They are used for recovery purposes; their purpose in life is to be used in the event of an instance or media failure.

If the power goes off on your database machine, causing an instance failure, Oracle will use the online redo logs to restore the system to exactly the point it was at immediately prior to the power outage. If your disk drive fails (a media failure), Oracle will use archived redo logs as well as online redo logs to recover a backup of the data that was on that drive to the correct point in time. Additionally, if you "accidentally" truncate a table or remove some critical information and commit the operation, you can restore a backup of the affected data and recover it to the point in time immediately prior to the "accident" using online and archived redo log files.

Archived redo log files are simply copies of old, full online redo log files. As the system fills up log files, the ARCH process will make a copy of the online redo log file in another location, and optionally make several other copies into local and remote locations as well. These archived redo log files are used to perform media recovery when a failure is caused by a disk drive going bad or some other physical fault. Oracle can take these archived redo log files and apply them to backups of the data files to catch them up to the rest of the database. They are the transaction history of the database.

Note With the advent of the Oracle 10g, we now have flashback technology. This allows us to perform flashback queries (i.e., query the data as of some point in time in the past), un-drop a database table, put a table back the way it was some time ago, and so on. As a result, the number of occasions where we need to perform a conventional recovery using backups and archived redo logs has decreased. However, performing a recovery is the DBA's most important job. Database recovery is the one thing a DBA is not allowed to get wrong.

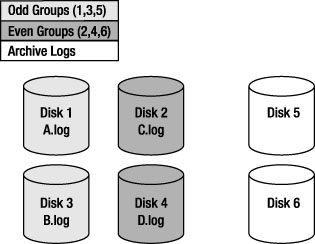

Every Oracle database has at least two online redo log groups with at least a single member (redo log file) in each group. These online redo log groups are used in a circular fashion. Oracle will write to the log files in group 1, and when it gets to the end of the files in group 1, it will switch to log file group 2 and begin writing to that one. When it has filled log file group 2, it will switch back to log file group 1 (assuming you have only two redo log file groups; if you have three, Oracle would, of course, proceed to the third group).

Redo logs, or transaction logs, are one of the major features that make a database a database. They are perhaps its most important recovery structure, although without the other pieces such as undo segments, distributed transaction recovery, and so on, nothing works. They are a major component of what sets a database apart from a conventional file system. The online redo logs allow us to effectively recover from a power outage—one that might happen while Oracle is in the middle of a write. The archived redo logs allow us to recover from media failures when, for instance, the hard disk goes bad or human error causes data loss. Without redo logs, the database would not offer any more protection than a file system.

What Is Undo?

Undo is conceptually the opposite of redo. Undo information is generated by the database as you make modifications to data to put it back the way it was before the modifications, in the event the transaction or statement you are executing fails for any reason or if you request it with a ROLLBACK statement. Whereas redo is used to replay a transaction in the event of failure—to recover the transaction—undo is used to reverse the effects of a statement or set of statements. Undo, unlike redo, is stored internally in the database in a special set of segments known as undo segments.

Note "Rollback segment" and "undo segment" are considered synonymous terms. Using manual undo management, the DBA will create "rollback segments." Using automatic undo management, the system will automatically create and destroy "undo segments" as necessary. These terms should be considered the same for all intents and purposes in this discussion.

It is a common misconception that undo is used to restore the database physically to the way it was before the statement or transaction executed, but this is not so. The database is logically restored to the way it was—any changes are logically undone—but the data structures, the database blocks themselves, may well be different after a rollback. The reason for this lies in the fact that, in any multiuser system, there will be tens or hundreds or thousands of concurrent transactions. One of the primary functions of a database is to mediate concurrent access to its data. The blocks that our transaction modifies are, in general, being modified by many other transactions as well. Therefore, we cannot just put a block back exactly the way it was at the start of our transaction—that could undo someone else's work!

For example, suppose our transaction executed an INSERT statement that caused the allocation of a new extent (i.e., it caused the table to grow). Our INSERT would cause us to get a new block, format it for use, and put some data on it. At that point, some other transaction might come along and insert data into this block. If we were to roll back our transaction, obviously we cannot unformat and unallocate this block. Therefore, when Oracle rolls back, it is really doing the logical equivalent of the opposite of what we did in the first place. For every INSERT, Oracle will do a DELETE. For every DELETE, Oracle will do an INSERT. For every UPDATE, Oracle will do an "anti-UPDATE," or an UPDATE that puts the row back the way it was prior to our modification.

Note This undo generation is not true for direct path operations, which have the ability to bypass undo generation on the table. We'll discuss these in more detail shortly.

How can we see this in action? Perhaps the easiest way is to follow these steps:

- Create an empty table.

- Full scan the table and observe the amount of I/O performed to read it.

- Fill the table with many rows (no commit).

- Roll back that work and undo it.

- Full scan the table a second time and observe the amount of I/O performed.

First, we'll create an empty table:

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> create table t

2 as

3 select *

4 from all_objects

5 where 1=0;

Table created.

And then we'll query it, with AUTOTRACE enabled in SQL*Plus to measure the I/O.

Note In this example, we will full scan the tables twice each time. The goal is to only measure the I/O performed the second time in each case. This avoids counting additional I/Os performed by the optimizer during any parsing and optimization that may occur.

The query initially takes three I/Os to full scan the table:

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> select * from t;

no rows selected

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> set autotrace traceonly statistics

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> select * from t;

no rows selected

Statistics

----------------------------------------------------------

0 recursive calls

0 db block gets

3 consistent gets

...

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> set autotrace off

Next, we'll add lots of data to the table. We'll make it "grow" but then roll it all back:

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> insert into t select * from all_objects;

48350 rows created.

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> rollback;

Rollback complete.

Now, if we query the table again, we'll discover that it takes considerably more I/Os to read the table this time:

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> select * from t;

no rows selected

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> set autotrace traceonly statistics

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> select * from t;

no rows selected

Statistics

----------------------------------------------------------

0 recursive calls

0 db block gets

689 consistent gets

...

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> set autotrace off

The blocks that our INSERT caused to be added under the table's high-water mark (HWM) are still there—formatted, but empty. Our full scan had to read them to see if they contained any rows. That shows that a rollback is a logical "put the database back the way it was" operation. The database will not be exactly the way it was, just logically the same.

How Redo and Undo Work Together

In this section, we'll take a look at how redo and undo work together in various scenarios. We will discuss, for example, what happens during the processing of an INSERT with regard to redo and undo generation and how Oracle uses this information in the event of failures at various points in time.

An interesting point to note is that undo information, stored in undo tablespaces or undo segments, is protected by redo as well. In other words, undo data is treated just like table data or index data—changes to undo generate some redo, which is logged. Why this is so will become clear in a moment when we discuss what happens when a system crashes. Undo data is added to the undo segment and is cached in the buffer cache just like any other piece of data would be.

Example INSERT-UPDATE-DELETE Scenario

As an example, we will investigate what might happen with a set of statements like this:

insert into t (x,y) values (1,1);

update t set x = x+1 where x = 1;

delete from t where x = 2;

We will follow this transaction down different paths and discover the answers to the following questions:

- What happens if the system fails at various points in the processing of these statements?

- What happens if we

ROLLBACKat any point? - What happens if we succeed and

COMMIT?

The INSERT

The initial INSERT INTO T statement will generate both redo and undo. The undo generated will be enough information to make the INSERT"go away." The redo generated by the INSERT INTO T will be enough information to make the insert "happen again."

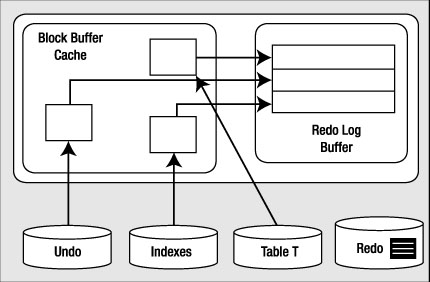

After the insert has occurred, we have the scenario illustrated in Figure 9-1.

Figure 9-1. State of the system after an INSERT

There are some cached, modified undo blocks, index blocks, and table data blocks. Each of these blocks is protected by entries in the redo log buffer.

Hypothetical Scenario: The System Crashes Right Now

Everything is OK. The SGA is wiped out, but we don't need anything that was in the SGA. It will be as if this transaction never happened when we restart. None of the blocks with changes got flushed to disk, and none of the redo got flushed to disk. We have no need of any of this undo or redo to recover from an instance failure.

Hypothetical Scenario: The Buffer Cache Fills Up Right Now

The situation is such that DBWR must make room and our modified blocks are to be flushed from the cache. In this case, DBWR will start by asking LGWR to flush the redo entries that protect these database blocks. Before DBWR can write any of the blocks that are changed to disk, LGWR must flush the redo information related to these blocks. This makes sense: if we were to flush the modified blocks for table T without flushing the redo entries associated with the undo blocks, and the system failed, we would have a modified table T block with no undo information associated with it. We need to flush the redo log buffers before writing these blocks out so that we can redo all of the changes necessary to get the SGA back into the state it is in right now, so that a rollback can take place.

This second scenario shows some of the foresight that has gone into all of this. The set of conditions described by "If we flushed table T blocks and did not flush the redo for the undo blocks and the system failed" is starting to get complex. It only gets more complex as we add users, and more objects, and concurrent processing, and so on.

At this point, we have the situation depicted in Figure 9-1. We have generated some modified table and index blocks. These have associated undo segment blocks, and all three types of blocks have generated redo to protect them. If you recall from our discussion of the redo log buffer in Chapter 4, it is flushed every three seconds, when it is one-third full or contains 1MB of buffered data, or whenever a commit takes place. It is very possible that at some point during our processing, the redo log buffer will be flushed. In that case, the picture looks like Figure 9-2.

Figure 9-2. State of the system after a redo log buffer flush

The UPDATE

The UPDATE will cause much of the same work as the INSERT to take place. This time, the amount of undo will be larger; we have some "before" images to save as a result of the update. Now, we have the picture shown in Figure 9-3.

Figure 9-3. State of the system after the UPDATE

We have more new undo segment blocks in the block buffer cache. To undo the update, if necessary, we have modified database table and index blocks in the cache. We have also generated more redo log buffer entries. Let's assume that some of our generated redo log from the insert is on disk and some is in cache.

Hypothetical Scenario: The System Crashes Right Now

Upon startup, Oracle would read the redo logs and find some redo log entries for our transaction. Given the state in which we left the system, with the redo entries for the insert in the redo log files and the redo for the update still in the buffer, Oracle would "roll forward" the insert. We would end up with a picture much like Figure 9-1, with some undo blocks (to undo the insert), modified table blocks (right after the insert), and modified index blocks (right after the insert). Oracle will discover that our transaction never committed and will roll it back since the system is doing crash recovery and, of course, our session is no longer connected. It will take the undo it just rolled forward in the buffer cache and apply it to the data and index blocks, making them look as they did before the insert took place. Now everything is back the way it was. The blocks that are on disk may or may not reflect the INSERT (it depends on whether or not our blocks got flushed before the crash). If they do, then the insert has been, in effect, undone, and when the blocks are flushed from the buffer cache, the data file will reflect that. If they do not reflect the insert, so be it—they will be overwritten later anyway.

This scenario covers the rudimentary details of a crash recovery. The system performs this as a two-step process. First it rolls forward, bringing the system right to the point of failure, and then it proceeds to roll back everything that had not yet committed. This action will resynchronize the data files. It replays the work that was in progress and undoes anything that has not yet completed.

Hypothetical Scenario: The Application Rolls Back the Transaction

At this point, Oracle will find the undo information for this transaction either in the cached undo segment blocks (most likely) or on disk if they have been flushed (more likely for very large transactions). It will apply the undo information to the data and index blocks in the buffer cache, or if they are no longer in the cache request, they are read from disk into the cache to have the undo applied to them. These blocks will later be flushed to the data files with their original row values restored.

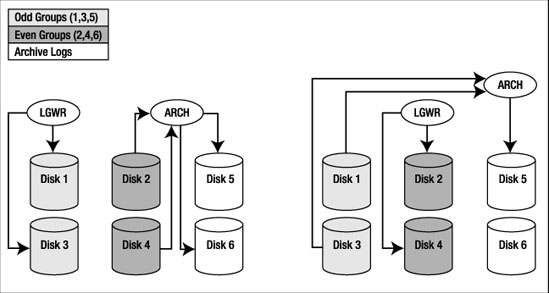

This scenario is much more common than the system crash. It is useful to note that during the rollback process, the redo logs are never involved. The only time redo logs are read is during recovery and archival. This is a key tuning concept: redo logs are written to. Oracle does not read them during normal processing. As long as you have sufficient devices so that when ARCH is reading a file, LGWR is writing to a different device, then there is no contention for redo logs. Many other databases treat the log files as "transaction logs." They do not have this separation of redo and undo. For those systems, the act of rolling back can be disastrous—the rollback process must read the logs their log writer is trying to write to. They introduce contention into the part of the system that can least stand it. Oracle's goal is to make it so that logs are written sequentially, and no one ever reads them while they are being written.

The DELETE

Again, undo is generated as a result of the DELETE, blocks are modified, and redo is sent over to the redo log buffer. This is not very different from before. In fact, it is so similar to the UPDATE that we are going to move right on to the COMMIT.

The COMMIT

We've looked at various failure scenarios and different paths, and now we've finally made it to the COMMIT. Here, Oracle will flush the redo log buffer to disk, and the picture will look like Figure 9-4.

Figure 9-4. State of the system after a COMMIT

The modified blocks are in the buffer cache; maybe some of them have been flushed to disk. All of the redo necessary to replay this transaction is safely on disk and the changes are now permanent. If we were to read the data directly from the data files, we probably would see the blocks as they existed before the transaction took place, as DBWR most likely has not written them yet. That is OK—the redo log files can be used to bring up to date those blocks in the event of a failure. The undo information will hang around until the undo segment wraps around and reuses those blocks. Oracle will use that undo to provide for consistent reads of the affected objects for any session that needs them.

Commit and Rollback Processing

It is important for us to understand how redo log files might impact us as developers. We will look at how the different ways we can write our code affect redo log utilization. We've already seen the mechanics of redo earlier in the chapter, and now we'll look at some specific issues. Many of these scenarios might be detected by you, but would be fixed by the DBA as they affect the database instance as a whole. We'll start with what happens during a COMMIT, and then get into commonly asked questions and issues surrounding the online redo logs.

What Does a COMMIT Do?

As a developer, you should have a good understanding of exactly what goes on during a COMMIT. In this section, we'll investigate what happens during the processing of the COMMIT statement in Oracle. A COMMIT is generally a very fast operation, regardless of the transaction size. You might think that the bigger a transaction (in other words, the more data it affects), the longer a COMMIT will take. This is not true. The response time of a COMMIT is generally "flat," regardless of the transaction size. This is because a COMMIT does not really have too much work to do, but what it does do is vital.

One of the reasons this is an important fact to understand and embrace is that it will lead you down the path of letting your transactions be as big as they should be. As we discussed in the previous chapter, many developers artificially constrain the size of their transactions, committing every so many rows, instead of committing when a logical unit of work has been performed. They do this in the mistaken belief that they are preserving scarce system resources, when in fact they are increasing them. If a COMMIT of one row takes X units of time, and the COMMIT of 1,000 rows takes the same X units of time, then performing work in a manner that does 1,000 one-row COMMITs will take an additional 1,000*X units of time to perform. By committing only when you have to (when the logical unit of work is complete), you will not only increase performance, but also reduce contention for shared resources (log files, various internal latches, and the like). A simple example demonstrates that it necessarily takes longer. We'll use a Java application, although you should expect similar results from most any client—except, in this case, PL/SQL (we'll discuss why that is after the example). To start, here is the sample table we'll be inserting into:

scott@ORA10G> desc test

Name Null? Type

----------------- -------- ------------

ID NUMBER

CODE VARCHAR2(20)

DESCR VARCHAR2(20)

INSERT_USER VARCHAR2(30)

INSERT_DATE DATE

Our Java program will accept two inputs: the number of rows to INSERT (iters) and how many rows between commits (commitCnt). It starts by connecting to the database, setting autocommit off (which should be done in all Java code), and then calling a doInserts() method a total of three times:

- Once just to warm up the routine (make sure all of the classes are loaded)

- A second time, specifying the number of rows to

INSERTalong with how many rows to commit at a time (i.e., commit every N rows) - A final time with the number of rows and number of rows to commit set to the same value (i.e., commit after all rows have been inserted)

It then closes the connection and exits. The main method is as follows:

import java.sql.*;

import oracle.jdbc.OracleDriver;

import java.util.Date;

public class perftest

{

public static void main (String arr[]) throws Exception

{

DriverManager.registerDriver(new oracle.jdbc.OracleDriver());

Connection con = DriverManager.getConnection

("jdbc:oracle:thin:@localhost.localdomain:1521:ora10g",

"scott", "tiger");

Integer iters = new Integer(arr[0]);

Integer commitCnt = new Integer(arr[1]);

con.setAutoCommit(false);

doInserts( con, 1, 1 );

doInserts( con, iters.intValue(), commitCnt.intValue() );

doInserts( con, iters.intValue(), iters.intValue() );

con.commit();

con.close();

}

Now, the method doInserts() is fairly straightforward. It starts by preparing (parsing) an INSERT statement so we can repeatedly bind/execute it over and over:

static void doInserts(Connection con, int count, int commitCount )

throws Exception

{

PreparedStatement ps =

con.prepareStatement

("insert into test " +

"(id, code, descr, insert_user, insert_date)"

+ " values (?,?,?, user, sysdate)");

It then loops over the number of rows to insert, binding and executing the INSERT over and over. Additionally, it is checking a row counter to see if it needs to COMMIT or not inside the loop. Note also that before and after the loop we are retrieving the time, so we can monitor elapsed times and report them:

int rowcnt = 0;

int committed = 0;

long start = new Date().getTime();

for (int i = 0; i < count; i++ )

{

ps.setInt(1,i);

ps.setString(2,"PS - code" + i);

ps.setString(3,"PS - desc" + i);

ps.executeUpdate();

rowcnt++;

if ( rowcnt == commitCount )

{

con.commit();

rowcnt = 0;

committed++;

}

}

con.commit();

long end = new Date().getTime();

System.out.println

("pstatement " + count + " times in " +

(end - start) + " milli seconds committed = "+committed);

}

}

Now we'll run this code repeatedly with different inputs:

$ java perftest 10000 1

pstatement 1 times in 4 milli seconds committed = 1

pstatement 10000 times in 11510 milli seconds committed = 10000

pstatement 10000 times in 2708 milli seconds committed = 1

$ java perftest 10000 10

pstatement 1 times in 4 milli seconds committed = 1

pstatement 10000 times in 3876 milli seconds committed = 1000

pstatement 10000 times in 2703 milli seconds committed = 1

$ java perftest 10000 100

pstatement 1 times in 4 milli seconds committed = 1

pstatement 10000 times in 3105 milli seconds committed = 100

pstatement 10000 times in 2694 milli seconds committed = 1

As you can see, the more often you commit, the longer it takes (your mileage will vary on this). This is just a single-user scenario—with multiple users doing the same work, all committing too frequently, the numbers will go up rapidly.

We've heard the same story, time and time again, with other similar situations. For example, we've seen how not using bind variables and performing hard parses frequently severely reduces concurrency due to library cache contention and excessive CPU utilization. Even when we switch to using bind variables, soft parsing too frequently, caused by closing cursors even though we are going to reuse them shortly, incurs massive overhead. We must perform operations only when we need to—a COMMIT is just another such operation. It is best to size our transactions based on business need, not based on misguided attempts to lessen resource usage on the database.

There are two contributing factors to the expense of the COMMIT in this example:

- We've obviously increased the round-trips to and from the database. If we commit every record, we are generating that much more traffic back and forth.

- Every time we commit, we must wait for our redo to be written to disk. This will result in a "wait." In this case, the wait is named "log file sync."

We can actually observe the latter easily by slightly modifying the Java application. We'll do two things:

- Add a call to

DBMS_MONITORto enable SQL tracing with wait events. In Oracle9i, we would usealter session set events'10046 trace name context forever, level 12'instead, asDBMS_MONITORis new in Oracle 10g. - Change the

con.commit()call to be a call to a SQL statement to perform the commit. If you use the built-in JDBCcommit()call, this does not emit a SQLCOMMITstatement to the trace file, andTKPROF, the tool used to format a trace file, will not report the time spent doing theCOMMIT.

So, we modify the doInserts() method as follows:

doInserts( con, 1, 1 );

Statement stmt = con.createStatement ();

stmt.execute

( "begin dbms_monitor.session_trace_enable(waits=>TRUE); end;" );

doInserts( con, iters.intValue(), iters.intValue() );

To the main method, we add the following:

PreparedStatement commit =

con.prepareStatement

("begin /* commit size = " + commitCount + " */ commit; end;" );

int rowcnt = 0;

int committed = 0;

...

if ( rowcnt == commitCount )

{

commit.executeUpdate();

rowcnt = 0;

committed++;

Upon running that application with 10,000 rows to insert, committing every row, the TKPROF report would show results similar to the following:

begin /* commit size = 1 */ commit; end;

....

Elapsed times include waiting on following events:

Event waited on Times Max. Wait Total Waited

---------------------------------------- Waited ---------- ------------

SQL*Net message to client 10000 0.00 0.01

SQL*Net message from client 10000 0.00 0.04

log file sync 8288 0.06 2.00

If we insert 10,000 rows and only commit when all 10,000 are inserted, we get results similar to the following:

begin /* commit size = 10000 */ commit; end;

....

Elapsed times include waiting on following events:

Event waited on Times Max. Wait Total Waited

----------------------------------------- Waited ---------- ------------

log file sync 1 0.00 0.00

SQL*Net message to client 1 0.00 0.00

SQL*Net message from client 1 0.00 0.00

When we committed after every INSERT, we waited almost every time—and if you wait a little bit of time but you wait often, then it all adds up. Fully two seconds of our runtime was spent waiting for a COMMIT to complete—in other words, waiting for LGWR to write the redo to disk. In stark contrast, when we committed once, we didn't wait very long (not a measurable amount of time actually). This proves that a COMMIT is a fast operation; we expect the response time to be more or less flat, not a function of the amount of work we've done.

So, why is a COMMIT's response time fairly flat, regardless of the transaction size? Before we even go to COMMIT in the database, we've already done the really hard work. We've already modified the data in the database, so we've already done 99.9 percent of the work. For example, operations such as the following have already taken place:

- Undo blocks have been generated in the SGA.

- Modified data blocks have been generated in the SGA.

- Buffered redo for the preceding two items has been generated in the SGA.

- Depending on the size of the preceding three items, and the amount of time spent, some combination of the previous data may be flushed onto disk already.

- All locks have been acquired.

When we COMMIT, all that is left to happen is the following:

- An SCN is generated for our transaction. In case you are not familiar with it, the SCN is a simple timing mechanism Oracle uses to guarantee the ordering of transactions and to enable recovery from failure. It is also used to guarantee read-consistency and checkpointing in the database. Think of the SCN as a ticker; every time someone

COMMITs, the SCN is incremented by one. LGWRwrites all of our remaining buffered redo log entries to disk and records the SCN in the online redo log files as well. This step is actually theCOMMIT. If this step occurs, we have committed. Our transaction entry is "removed" fromV$TRANSACTION—this shows that we have committed.- All locks recorded in

V$LOCKheld by our session are released, and everyone who was enqueued waiting on locks we held will be woken up and allowed to proceed with their work. - Some of the blocks our transaction modified will be visited and "cleaned out" in a fast mode if they are still in the buffer cache. Block cleanout refers to the lock-related information we store in the database block header. Basically, we are cleaning out our transaction information on the block, so the next person who visits the block won't have to. We are doing this in a way that need not generate redo log information, saving considerable work later (this is discussed more fully in the upcoming "Block Cleanout" section).

As you can see, there is very little to do to process a COMMIT. The lengthiest operation is, and always will be, the activity performed by LGWR, as this is physical disk I/O. The amount of time spent by LGWR here will be greatly reduced by the fact that it has already been flushing the contents of the redo log buffer on a recurring basis. LGWR will not buffer all of the work you do for as long as you do it; rather, it will incrementally flush the contents of the redo log buffer in the background as you are going along. This is to avoid having a COMMIT wait for a very long time in order to flush all of your redo at once.

So, even if we have a long-running transaction, much of the buffered redo log it generates would have been flushed to disk, prior to committing. On the flip side of this is the fact that when we COMMIT, we must wait until all buffered redo that has not been written yet is safely on disk. That is, our call to LGWR is a synchronous one. While LGWR may use asynchronous I/O to write in parallel to our log files, our transaction will wait for LGWR to complete all writes and receive confirmation that the data exists on disk before returning.

Now, earlier I mentioned that we were using a Java program and not PL/SQL for a reason—and that reason is a PL/SQL commit-time optimization. I said that our call to LGWR is a synchronous one, and that we wait for it to complete its write. That is true in Oracle 10g Release 1 and before for every programmatic language except PL/SQL. The PL/SQL engine, realizing that the client does not know whether or not a COMMIT has happened in the PL/SQL routine until the PL/SQL routine is completed, does an asynchronous commit. It does not wait for LGWR to complete; rather, it returns from the COMMIT call immediately. However, when the PL/SQL routine is completed, when we return from the database to the client, the PL/SQL routine will wait for LGWR to complete any of the outstanding COMMITs. So, if you commit 100 times in PL/SQL and then return to the client, you will likely find you waited for LGWR once—not 100 times—due to this optimization. Does this imply that committing frequently in PL/SQL is a good or OK idea? No, not at all—just that it is not as bad an idea as it is in other languages. The guiding rule is to commit when your logical unit of work is complete—not before.

Note This commit-time optimization in PL/SQL may be suspended when you are performing distributed transactions or Data Guard in maximum availability mode. Since there are two participants, PL/SQL must wait for the commit to actually be complete before continuing on.

To demonstrate that a COMMIT is a "flat response time" operation, we'll generate varying amounts of redo and time the INSERTs and COMMITs. To do this, we'll again use AUTOTRACE in SQL*Plus. We'll start with a big table of test data we'll insert into another table and an empty table:

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> @big_table 100000

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> create table t as select * from big_table where 1=0;

Table created.

And then in SQL*Plus we'll run the following:

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> set timing on

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> set autotrace on statistics;

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> insert into t select * from big_table where rownum <= 10;

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> commit;

We monitor the redo size statistic presented by AUTOTRACE and the timing information presented by set timing on. I performed this test and varied the number of rows inserted from 10 to 100,000 in multiples of 10. Table 9-1 shows my observations.

Table 9-1. Time to COMMIT by Transaction Size*

| Rows Inserted | Time to Insert (Seconds) | Redo Size (Bytes) | Commit Time (Seconds) |

| * This test was performed on a single-user machine with an 8MB log buffer and two 512MB online redo log files. | |||

| 10 | 0.05 | 116 | 0.06 |

| 100 | 0.08 | 3,594 | 0.04 |

| 1,000 | 0.07 | 372,924 | 0.06 |

| 10,000 | 0.25 | 3,744,620 | 0.06 |

| 100,000 | 1.94 | 37,843,108 | 0.07 |

As you can see, as we generate varying amount of redo, from 116 bytes to 37MB, the difference in time to COMMIT is not measurable using a timer with a one hundredth of a second resolution. As we were processing and generating the redo log, LGWR was constantly flushing our buffered redo information to disk in the background. So, when we generated 37MB of redo log information, LGWR was busy flushing every 1MB or so. When it came to the COMMIT, there wasn't much left to do—not much more than when we created ten rows of data. You should expect to see similar (but not exactly the same) results, regardless of the amount of redo generated.

What Does a ROLLBACK Do?

By changing the COMMIT to ROLLBACK, we can expect a totally different result. The time to roll back will definitely be a function of the amount of data modified. I changed the script developed in the previous section to perform a ROLLBACK instead (simply change the COMMIT to ROLLBACK) and the timings are very different (see Table 9-2).

Table 9-2. Time to ROLLBACK by Transaction Size

| Rows Inserted | Rollback Time (Seconds) | Commit Time (Seconds) |

| 10 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| 100 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| 1,000 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| 10,000 | 0.22 | 0.06 |

| 100,000 | 1.46 | 0.07 |

This is to be expected, as a ROLLBACK has to physically undo the work we've done. Similar to a COMMIT, a series of operations must be performed. Before we even get to the ROLLBACK, the database has already done a lot of work. To recap, the following would have happened:

- Undo segment records have been generated in the SGA.

- Modified data blocks have been generated in the SGA.

- A buffered redo log for the preceding two items has been generated in the SGA.

- Depending on the size of the preceding three items, and the amount of time spent, some combination of the previous data may be flushed onto disk already.

- All locks have been acquired.

When we ROLLBACK,

- We undo all of the changes made. This is accomplished by reading the data back from the undo segment, and in effect, reversing our operation and then marking the undo entry as applied. If we inserted a row, a

ROLLBACKwill delete it. If we updated a row, a rollback will reverse the update. If we deleted a row, a rollback will re-insert it again. - All locks held by our session are released, and everyone who was enqueued waiting on locks we held will be released.

A COMMIT, on the other hand, just flushes any remaining data in the redo log buffers. It does very little work compared to a ROLLBACK. The point here is that you don't want to roll back unless you have to. It is expensive since you spend a lot of time doing the work, and you'll also spend a lot of time undoing the work. Don't do work unless you're sure you are going to want to COMMIT it. This sounds like common sense—of course I wouldn't do all of the work unless I wanted to COMMIT it. Many times, however, I've seen a situation where a developer will use a "real" table as a temporary table, fill it up with data, report on it, and then roll back to get rid of the temporary data. In the next section, we'll talk about true temporary tables and how to avoid this issue.

Investigating Redo

As a developer, it's often important to be able to measure how much redo your operations generate. The more redo you generate, the longer your operations will take, and the slower the entire system will be. You are not just affecting your session, but every session. Redo manage-ment is a point of serialization within the database. There is just one LGWR in any Oracle instance, and eventually all transactions end up at LGWR, asking it to manage their redo and COMMIT their transaction. The more it has to do, the slower the system will be. By seeing how much redo an operation tends to generate, and testing more than one approach to a problem, you can find the best way to do things.

Measuring Redo

It is pretty straightforward to see how much redo is being generated, as shown earlier in the chapter. I used the AUTOTRACE built-in feature of SQL*Plus. But AUTOTRACE works only with simple DML—it cannot, for example, be used to view what a stored procedure call did. For that, we'll need access to two dynamic performance views:

V$MYSTAT, which has just our session's statistics in itV$STATNAME, which tells us what each row inV$MYSTATrepresents (the name of the statistic we are looking at)

I do these sorts of measurements so often that I use two scripts I call mystat and mystat2. The mystat.sql script saves the beginning value of the statistic I'm interested in, such as redo size, in a SQL*Plus variable:

set verify off

column value new_val V

define S="&1"

set autotrace off

select a.name, b.value

from v$statname a, v$mystat b

where a.statistic# = b.statistic#

and lower(a.name) like '%' || lower('&S')||'%'

/

The mystat2.sql script simply prints out the difference between the beginning value and the end value of that statistic:

set verify off

select a.name, b.value V, to_char(b.value-&V,'999,999,999,999') diff

from v$statname a, v$mystat b

where a.statistic# = b.statistic#

and lower(a.name) like '%' || lower('&S')||'%'

/

Now we're ready to measure how much redo a given transaction would generate. All we need to do is this:

@mystat "redo size"

...process...

@mystat2

for example:

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> @mystat "redo size"

NAME VALUE

------------------------------ ----------

redo size 496

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> insert into t select * from big_table;

100000 rows created.

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> @mystat2

NAME V DIFF

------------------------------ ---------- ----------------

redo size 37678732 37,678,236

As just shown, we generated about 37MB of redo for that INSERT. Perhaps you would like to compare that to the redo generated by a direct path INSERT, as follows:

Note The example in this section was performed on a NOARCHIVELOG mode database. If you are in ARCHIVELOG mode, the table would have to be NOLOGGING to observe this dramatic change. We will investigate the NOLOGGING attribute in more detail shortly in the section "Setting NOLOGGING in SQL." But please make sure to coordinate all nonlogged operations with your DBA on a "real" system.

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> @mystat "redo size"

NAME VALUE

------------------------------ ----------

redo size 37678732

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> insert /*+ APPEND */ into t select * from big_table;

100000 rows created.

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> @mystat2

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> set echo off

NAME V DIFF

------------------------------ ---------- ----------------

redo size 37714328 35,596

The method I outline using the V$MYSTAT view is useful in general for seeing the side effects of various options. The mystat.sql script is useful for small tests, with one or two operations, but what if we want to perform a big series of tests? This is where a little test harness can come in handy, and in the next section we'll set up and use this test harness alongside a table to log our results, to investigate the redo generated by BEFORE triggers.

Redo Generation and BEFORE/AFTER Triggers

I'm often asked the following question: "Other than the fact that you can modify the values of a row in a BEFORE trigger, are there any other differences between BEFORE and AFTER triggers?" Well, as it turns out, yes there are. A BEFORE trigger tends to add additional redo information, even if it does not modify any of the values in the row. In fact, this is an interesting case study, and using the techniques described in the previous section, we'll discover that

- A

BEFOREorAFTERtrigger does not affect the redo generated byDELETEs. - In Oracle9i Release 2 and before, an

INSERTgenerates extra redo in the same amount for either aBEFOREor anAFTERtrigger. In Oracle 10g, it generates no additional redo. - In all releases up to (and including) Oracle9i Release 2, the redo generated by an

UPDATEis affected only by the existence of aBEFOREtrigger. AnAFTERtrigger adds no additional redo. However, in Oracle 10g, the behavior is once again different. Specifically,- Overall, the amount of redo generated during an update on a table without a trigger is less than in Oracle9i and before. This seems to be the crux of what Oracle wanted to achieve: to decrease the amount of redo generated by an update on a table without any triggers.

- The amount of redo generated during an update on a table with a

BEFOREtrigger is higher in Oracle 10g than in 9i. - The amount of redo generated with the

AFTERtrigger is the same as in 9i.

To perform this test, we'll use a table T defined as follows:

create table t ( x int, y char(N), z date );

but we'll create it with varying sizes for N. In this example, we'll use N = 30, 100, 500, 1,000, and 2,000 to achieve rows of varying widths. After we run our test for various sizes of the Y column, we'll analyze the results. I used a simple log table to capture the results of my many runs:

create table log ( what varchar2(15), -- will be no trigger, after or before

op varchar2(10), -- will be insert/update or delete

rowsize int, -- will be the size of Y

redo_size int, -- will be the redo generated

rowcnt int ) -- will be the count of rows affected

I used the following DO_WORK stored procedure to generate my transactions and record the redo generated. The subprocedure REPORT is a local procedure (only visible in the DO_WORK procedure), and it simply reports what happened on the screen and captures the findings into our LOG table:

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> create or replace procedure do_work( p_what in varchar2 )

2 as

3 l_redo_size number;

4 l_cnt number := 200;

5

6 procedure report( l_op in varchar2 )

7 is

8 begin

9 select v$mystat.value-l_redo_size

10 into l_redo_size

11 from v$mystat, v$statname

12 where v$mystat.statistic# = v$statname.statistic#

13 and v$statname.name = 'redo size';

14

15 dbms_output.put_line(l_op || ' redo size = ' || l_redo_size ||

16 ' rows = ' || l_cnt || ' ' ||

17 to_char(l_redo_size/l_cnt,'99,999.9') ||

18 ' bytes/row' );

19 insert into log

20 select p_what, l_op, data_length, l_redo_size, l_cnt

21 from user_tab_columns

22 where table_name = 'T'

23 and column_name = 'Y';

24 end;

The local procedure SET_REDO_SIZE queries V$MYSTAT and V$STATNAME to retrieve the current amount of redo our session has generated thus far. It sets the variable L_REDO_SIZE in the procedure to that value:

25 procedure set_redo_size

26 as

27 begin

28 select v$mystat.value

29 into l_redo_size

30 from v$mystat, v$statname

31 where v$mystat.statistic# = v$statname.statistic#

32 and v$statname.name = 'redo size';

33 end;

And then there is the main routine. It collects the current redo size, runs an INSERT/UPDATE/DELETE, and then saves the redo generated by that operation to the LOG table:

34 begin

35 set_redo_size;

36 insert into t

37 select object_id, object_name, created

38 from all_objects

39 where rownum <= l_cnt;

40 l_cnt := sql%rowcount;

41 commit;

42 report('insert'),

43

44 set_redo_size;

45 update t set y=lower(y);

46 l_cnt := sql%rowcount;

47 commit;

48 report('update'),

49

50 set_redo_size;

51 delete from t;

52 l_cnt := sql%rowcount;

53 commit;

54 report('delete'),

55 end;

56 /

Now, once we have this in place, we set the width of column Y to 2,000. We then run the following script to test the three scenarios, namely no trigger, BEFORE trigger, and AFTER trigger:

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> exec do_work('no trigger'),

insert redo size = 505960 rows = 200 2,529.8 bytes/row

update redo size = 837744 rows = 200 4,188.7 bytes/row

delete redo size = 474164 rows = 200 2,370.8 bytes/row

PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> create or replace trigger before_insert_update_delete

2 before insert or update or delete on T for each row

3 begin

4 null;

5 end;

6 /

Trigger created.

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> truncate table t;

Table truncated.

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> exec do_work('before trigger'),

insert redo size = 506096 rows = 200 2,530.5 bytes/row

update redo size = 897768 rows = 200 4,488.8 bytes/row

delete redo size = 474216 rows = 200 2,371.1 bytes/row

PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> drop trigger before_insert_update_delete;

Trigger dropped.

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> create or replace trigger after_insert_update_delete

2 after insert or update or delete on T

3 for each row

4 begin

5 null;

6 end;

7 /

Trigger created.

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> truncate table t;

Table truncated.

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> exec do_work( 'after trigger' );

insert redo size = 505972 rows = 200 2,529.9 bytes/row

update redo size = 856636 rows = 200 4,283.2 bytes/row

delete redo size = 474176 rows = 200 2,370.9 bytes/row

PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

The preceding output was from a run where the size of Y was 2,000 bytes. After all of the runs were complete, we are able to query the LOG table and see the following:

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> break on op skip 1

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> set numformat 999,999

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> select op, rowsize, no_trig,

before_trig-no_trig, after_trig-no_trig

2 from

3 ( select op, rowsize,

4 sum(decode( what, 'no trigger', redo_size/rowcnt,0 ) ) no_trig,

5 sum(decode( what, 'before trigger', redo_size/rowcnt, 0 ) ) before_trig,

6 sum(decode( what, 'after trigger', redo_size/rowcnt, 0 ) ) after_trig

7 from log

8 group by op, rowsize

9 )

10 order by op, rowsize

11 /

OP ROWSIZE NO_TRIG BEFORE_TRIG-NO_TRIG AFTER_TRIG-NO_TRIG

---------- -------- -------- ------------------- ------------------------

delete 30 291 0 0

100 364 −1 −0

500 785 −0 0

1,000 1,307 −0 −0

2,000 2,371 0 −0

insert 30 296 0 −0

100 367 0 0

500 822 1 1

1,000 1,381 −0 −0

2,000 2,530 0 0

update 30 147 358 152

100 288 363 157

500 1,103 355 150

1,000 2,125 342 137

2,000 4,188 300 94

15 rows selected.

Now, I was curious if the log mode (ARCHIVELOG versus NOARCHIVELOG mode) would affect these results. I discovered that the answer is no, the numbers were identical in both modes. I was curious about why the results were very different from the first edition of Expert One-on-One Oracle, upon which this book you are reading is loosely based. That book was released when Oracle8i version 8.1.7 was current. The Oracle 10g results just shown differed greatly from Oracle8i, but the Oracle9i results shown in this table resembled the Oracle8i results closely:

OP ROWSIZE NO_TRIG BEFORE_TRIG-NO_TRIG AFTER_TRIG-NO_TRIG

---------- -------- -------- ------------------- -----------------

delete 30 279 −0 −0

100 351 −0 −0

500 768 1 0

1,000 1,288 0 0

2,000 2,356 0 −11

insert 30 61 221 221

100 136 217 217

500 599 199 198

1,000 1,160 181 181

2,000 2,311 147 147

update 30 302 197 0

100 438 197 0

500 1,246 195 0

1,000 2,262 185 0

2,000 4,325 195 −1

15 rows selected.

I discovered that the way triggers affect the redo generated by a transaction materially changed between Oracle9i Release 2 and Oracle 10g. The changes are easy to see here:

- A

DELETEwas not and is still not affected by the presence of a trigger at all. - An

INSERTwas affected in Oracle9i Release 2 and before, and at first glance you might say Oracle 10g optimized theINSERTso it would not be affected, but if you look at the total redo generated without a trigger in Oracle 10g, you'll see it is the same amount that was generated in Oracle9i Release 2 and before with a trigger. So, it is not that Oracle 10g reduced the amount of redo generated by anINSERTin the presence of a trigger, but rather that the amount of redo generated is constant—and anINSERTin Oracle 10g will generate more redo than in Oracle9i without a trigger. - An

UPDATEwas affected by aBEFOREtrigger in 9i but not anAFTERtrigger. At first glance it would appear that Oracle 10g changed that so as both triggers affect it. But upon closer inspection, we can see that what actually happened was that the redo generated by anUPDATEwithout a trigger was decreased in Oracle 10g by the amount that theUPDATEgenerates with the trigger. So the opposite of what happened withINSERTs between 9i and 10g happened withUPDATEs—the amount of redo generated without a trigger decreased.

Table 9-3 summarizes the effects of a trigger on the amount of redo generated by a DML operation in both Oracle9i and before and Oracle 10g.

Table 9-3. Effect of Triggers on Redo Generation

| DML Operation | AFTER Trigger Pre-10g |

BEFORE Trigger, Pre-10g |

AFTER Trigger, 10g |

BEFORE Trigger, 10g |

DELETE |

No affect | No affect | No affect | No affect |

INSERT |

Increased redo | Increased redo | Constant redo | Constant redo |

UPDATE |

Increased redo | No affect | Increased redo | Increased redo |

So, now you know how to estimate the amount of redo, which every developer should be able to do. You can

- Estimate your "transaction" size (how much data you modify).

- Add 10 to 20 percent overhead of the amount of data you modify, depending on the number of rows you will be modifying. The more rows, the less overhead.

- Double this value for

UPDATEs.

In most cases, this will be a good estimate. The doubling on the UPDATEs is a guess—it really depends on how you modify the data. The doubling assumes you take a row of X bytes, and UPDATE it to be a row of X bytes. If you take a small row and make it big, you will not double the value (it will behave more like an INSERT). If you take a big row and make it small, you will not double the value (it will behave like a DELETE). The doubling is a "worst-case" number, as there are various options and features that will impact this—for example, the existence of indexes (or lack thereof, as in my case) will contribute to the bottom line. The amount of work that must be done to maintain the index structure may vary from UPDATE to UPDATE, and so on. Side effects from triggers have to be taken into consideration (in addition to the fixed overhead described previously). Implicit operations performed on your behalf, such as an ON DELETE CASCADE setting on a foreign key, must be considered as well. This will allow you to estimate the amount of redo for sizing/performance purposes. Only real-world testing will tell you for sure. Given the preceding script, you can see how to measure this for yourself, for any of your objects and transactions.

Can I Turn Off Redo Log Generation?

This question is often asked. The simple short answer is no, since redo logging is crucial for the database; it is not overhead and it is not a waste. You do need it, regardless of whether you believe you do or not. It is a fact of life, and it is the way the database works. If in fact you "turned off redo," then any temporary failure of disk drives, power, or some software crash would render the entire database unusable and unrecoverable. However, that said, there are some operations that can be done without generating redo log in some cases.

Note As of Oracle9i Release 2, a DBA may place the database into FORCE LOGGING mode. In that case, all operations are logged. The query SELECT FORCE_LOGGING FROM V$DATABASE may be used to see if logging is going to be forced or not. This feature is in support of Data Guard, a disaster recovery feature of Oracle that relies on redo to maintain a standby database copy.

Setting NOLOGGING in SQL

Some SQL statements and operations support the use of a NOLOGGING clause. This does not mean that all operations against the object will be performed without generating a redo log, just that some very specific operations will generate significantly less redo than normal. Note that I said "significantly less redo," not "no redo." All operations will generate some redo—all data dictionary operations will be logged regardless of the logging mode. The amount of redo generated can be significantly less. For this example of the NOLOGGING clause, I ran the following in a database running in ARCHIVELOG mode:

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> select log_mode from v$database;

LOG_MODE

------------

ARCHIVELOG

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> @mystat "redo size"

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> set echo off

NAME VALUE

---------- ----------

redo size 5846068

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> create table t

2 as

3 select * from all_objects;

Table created.

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> @mystat2

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> set echo off

NAME V DIFF

---------- ---------- ----------------

redo size 11454472 5,608,404

That CREATE TABLE generated about 5.5MB of redo information. We'll drop and re-create the table, in NOLOGGING mode this time:

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> drop table t;

Table dropped.

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> @mystat "redo size"

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> set echo off

NAME VALUE

---------- ----------

redo size 11459508

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> create table t

2 NOLOGGING

3 as

4 select * from all_objects;

Table created.

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> @mystat2

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> set echo off

NAME V DIFF

---------- ---------- ----------------

redo size 11540676 81,168

This time, there is only 80KB of redo generated.

As you can see, this makes a tremendous difference—5.5MB of redo versus 80KB. The 5.5MB is the actual table data itself; it was written directly to disk, with no redo log generated for it.

If you test this on a NOARCHIVELOG mode database, you will not see any differences. The CREATE TABLE will not be logged, with the exception of the data dictionary modifications, in a NOARCHIVELOG mode database. If you would like to see the difference on a NOARCHIVELOG mode database, you can replace the DROP TABLE and CREATE TABLE with DROP INDEX and CREATE INDEX on table T. These operations are logged by default, regardless of the mode in which the database is running. This example also points out a valuable tip: test your system in the mode it will be run in production, as the behavior may be different. Your production system will be running in ARCHIVELOG mode; if you perform lots of operations that generate redo in this mode, but not in NOARCHIVELOG mode, you'll want to discover this during testing, not during rollout to the users!

Of course, it is now obvious that you will do everything you can with NOLOGGING, right? In fact, the answer is a resounding no. You must use this mode very carefully, and only after discussing the issues with the person in charge of backup and recovery. Let's say you create this table and it is now part of your application (e.g., you used a CREATE TABLE AS SELECT NOLOGGING as part of an upgrade script). Your users modify this table over the course of the day. That night, the disk that the table is on fails. "No problem," the DBA says. "We are running in ARCHIVELOG mode, and we can perform media recovery." The problem is, however, that the initially created table, since it was not logged, is not recoverable from the archived redo log. This table is unrecoverable and this brings out the most important point about NOLOGGING operations: they must be coordinated with your DBA and the system as a whole. If you use them and others are not aware of that fact, you may compromise the ability of your DBA to recover your database fully after a media failure. They must be used judiciously and carefully.

The important things to note about NOLOGGING operations are as follows:

- Some amount of redo will be generated, as a matter of fact. This redo is to protect the data dictionary. There is no avoiding this at all. It could be of a significantly lesser amount than before, but there will be some.

NOLOGGINGdoes not prevent redo from being generated by all subsequent operations. In the preceding example, I did not create a table that is never logged. Only the single, individual operation of creating the table was not logged. All subsequent "normal" operations such asINSERTs,UPDATEs, andDELETEs will be logged. Other special operations, such as a direct path load using SQL*Loader, or a direct path insert using theINSERT /*+ APPEND */syntax, will not be logged (unless and until youALTERthe table and enable full logging again). In general, however, the operations your application performs against this table will be logged.- After performing

NOLOGGINGoperations in anARCHIVELOGmode database, you must take a new baseline backup of the affected data files as soon as possible, in order to avoid losing subsequent changes to these objects due to media failure. We wouldn't actually lose the subsequent changes, as these are in the redo log; we would lose the data to apply the changes to.

Setting NOLOGGING on an Index

There are two ways to use the NOLOGGING option. You have already seen one method—that of embedding the NOLOGGING keyword in the SQL command. The other method, which involves setting the NOLOGGING attribute on the segment (index or table), allows operations to be performed implicitly in a NOLOGGING mode. For example, I can alter an index or table to be NOLOGGING by default. This means for the index that subsequent rebuilds of this index will not be logged (the index will not generate redo; other indexes and the table itself might, but this index will not):

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> create index t_idx on t(object_name);

Index created.

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> @mystat "redo size"

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> set echo off

NAME VALUE

---------- ----------

redo size 13567908

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> alter index t_idx rebuild;

Index altered.

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> @mystat2

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> set echo off

NAME V DIFF

---------- ---------- ----------------

redo size 15603436 2,035,528

When the index is in LOGGING mode (the default), a rebuild of it generated 2MB of redo log. However, we can alter the index:

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> alter index t_idx nologging;

Index altered.

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> @mystat "redo size"

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> set echo off

NAME VALUE

---------- ----------

redo size 15605792

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> alter index t_idx rebuild;

Index altered.

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> @mystat2

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> set echo off

NAME V DIFF

---------- ---------- ----------------

redo size 15668084 62,292

and now it generates a mere 61KB of redo. But that index is "unprotected" now, if the data files it was located in failed and had to be restored from a backup, we would lose that index data. Understanding that fact is crucial. The index is not recoverable right now—we need a backup to take place. Alternatively, the DBA could just re-create the index as we can re-create the index directly from the table data as well.

NOLOGGING Wrap-Up

The operations that may be performed in a NOLOGGING mode are as follows:

- Index creations and

ALTERs (rebuilds). - Bulk

INSERTs into a table using a "direct path insert" such as that available via the/*+ APPEND */hint or SQL*Loader direct path loads. The table data will not generate redo, but all index modifications will (the indexes on this nonlogged table will generate redo!). LOBoperations (updates to large objects do not have to be logged).- Table creations via

CREATE TABLE AS SELECT. - Various

ALTER TABLEoperations such asMOVEandSPLIT.

Used appropriately on an ARCHIVELOG mode database, NOLOGGING can speed up many operations by dramatically reducing the amount of redo log generated. Suppose you have a table you need to move from one tablespace to another. You can schedule this operation to take place immediately before a backup occurs—you would ALTER the table to be NOLOGGING, move it, rebuild the indexes (without logging as well), and then ALTER the table back to logging mode. Now, an operation that might have taken X hours can happen in X/2 hours perhaps (I'm not promising a 50 percent reduction in runtime!). The appropriate use of this feature includes involvement of the DBA, or whoever is responsible for database backup and recovery or any standby databases. If that person is not aware of the use of this feature, and a media failure occurs, you may lose data, or the integrity of the standby database might be compromised. This is something to seriously consider.

Why Can't I Allocate a New Log?

I get this question all of the time. You are getting warning messages to this effect (this will be found in alert.log on your server):

Thread 1 cannot allocate new log, sequence 1466

Checkpoint not complete

Current log# 3 seq# 1465 mem# 0: /home/ora10g/oradata/ora10g/redo03.log

It might say Archival required instead of Checkpoint not complete, but the effect is pretty much the same. This is really something the DBA should be looking out for. This message will be written to alert.log on the server whenever the database attempts to reuse an online redo log file and finds that it cannot. This will happen when DBWR has not yet finished checkpointing the data protected by the redo log or ARCH has not finished copying the redo log file to the archive destination. At this point in time, the database effectively halts as far as the end user is concerned. It stops cold. DBWR or ARCH will be given priority to flush the blocks to disk. Upon completion of the checkpoint or archival, everything goes back to normal. The reason the database suspends user activity is that there is simply no place to record the changes the users are making. Oracle is attempting to reuse an online redo log file, but because either the file would be needed to recover the database in the event of a failure (Checkpoint not complete), or the archiver has not yet finished copying it (Archival required), Oracle must wait (and the end users will wait) until the redo log file can safely be reused.

If you see that your sessions spend a lot of time waiting on a "log file switch," "log buffer space," or "log file switch checkpoint or archival incomplete," then you are most likely hitting this. You will notice it during prolonged periods of database modifications if your log files are sized incorrectly, or because DBWR and ARCH need to be tuned by the DBA or system administrator. I frequently see this issue with the "starter" database that has not been customized. The "starter" database typically sizes the redo logs far too small for any sizable amount of work (including the initial database build of the data dictionary itself). As soon as you start loading up the database, you will notice that the first 1,000 rows go fast, and then things start going in spurts: 1,000 go fast, then hang, then go fast, then hang, and so on. These are the indications you are hitting this condition.

There are a couple of things you can do to solve this issue:

- Make

DBWRfaster. Have your DBA tuneDBWRby enablingASYNCI/O, usingDBWRI/O slaves, or using multipleDBWRprocesses. Look at the I/O on the system and see if one disk, or a set of disks, is "hot" so you need to therefore spread out the data. The same general advice applies forARCHas well. The pros of this are that you get "something for nothing" here—increased performance without really changing any logic/structures/code. There really are no downsides to this approach. - Add more redo log files. This will postpone the

Checkpoint not completein some cases and, after a while, it will postpone theCheckpoint not completeso long that it perhaps doesn't happen (because you gaveDBWRenough breathing room to checkpoint). The same applies to theArchival requiredmessage. The benefit to this approach is the removal of the "pauses" in your system. The downside is it consumes more disk, but the benefit far outweighs any downside here. - Re-create the log files with a larger size. This will extend the amount of time between the time you fill the online redo log and the time you need to reuse it. The same applies to the

Archival requiredmessage, if the redo log file usage is "bursty." If you have a period of massive log generation (nightly loads, batch processes) followed by periods of relative calm, then having larger online redo logs can buy enough time forARCHto catch up during the calm periods. The pros and cons are identical to the preceding approach of adding more files. Additionally, it may postpone a checkpoint from happening until later, since checkpoints happen at each log switch (at least), and the log switches will now be further apart. - Cause checkpointing to happen more frequently and more continuously. Use a smaller block buffer cache (not entirely desirable) or various parameter settings such as

FAST_START_MTTR_TARGET,LOG_CHECKPOINT_INTERVAL, andLOG_CHECKPOINT_TIMEOUT. This will forceDBWRto flush dirty blocks more frequently. The benefit to this approach is that recovery time from a failure is reduced. There will always be less work in the online redo logs to be applied. The downside is that blocks may be written to disk more frequently if they are modified often. The buffer cache will not be as effective as it could be, and it can defeat the block cleanout mechanism discussed in the next section.

The approach you take will depend on your circumstances. This is something that must be fixed at the database level, taking the entire instance into consideration.

Block Cleanout

In this section, we'll discuss block cleanouts, or the removal of "locking"-related information on the database blocks we've modified. This concept is important to understand when we talk about the infamous ORA-01555: snapshot too old error in a subsequent section.

If you recall in Chapter 6, we talked about data locks and how they are managed. I described how they are actually attributes of the data, stored on the block header. A side effect of this is that the next time that block is accessed, we may have to "clean it out"—in other words, remove the transaction information. This action generates redo and causes the block to become dirty if it wasn't already, meaning that a simple SELECT may generate redo and may cause lots of blocks to be written to disk with the next checkpoint. Under most normal circumstances, however, this will not happen. If you have mostly small- to medium-sized transactions (OLTP), or you have a data warehouse that performs direct path loads or uses DBMS_STATS to analyze tables after load operations, then you'll find the blocks are generally "cleaned" for you. If you recall from the earlier section titled "What Does a COMMIT Do?" one of the steps of COMMIT-time processing is to revisit our blocks if they are still in the SGA, if they are accessible (no one else is modifying them), and then clean them out. This activity is known as a commit cleanout and is the activity that cleans out the transaction information on our modified block. Optimally, our COMMIT can clean out the blocks so that a subsequent SELECT (read) will not have to clean it out. Only an UPDATE of this block would truly clean out our residual transaction information, and since the UPDATE is already generating redo, the cleanout is not noticeable.

We can force a cleanout to not happen, and therefore observe its side effects, by understanding how the commit cleanout works. In a commit list associated with our transaction, Oracle will record lists of blocks we have modified. Each of these lists is 20 blocks long, and Oracle will allocate as many of these lists as it needs—up to a point. If the sum of the blocks we modify exceeds 10 percent of the block buffer cache size, Oracle will stop allocating new lists for us. For example, if our buffer cache is set to cache 3,000 blocks, Oracle will maintain a list of up to 300 blocks (10 percent of 3,000) for us. Upon COMMIT, Oracle will process each of these lists of 20 block pointers, and if the block is still available, it will perform a fast cleanout. So, as long as the number of blocks we modify does not exceed 10 percent of the number of blocks in the cache and our blocks are still in the cache and available to us, Oracle will clean them out upon COMMIT. Otherwise, it just skips them (i.e., does not clean them out).

Given this understanding, we can set up artificial conditions to see how the cleanout works. I set my DB_CACHE_SIZE to a low value of 4MB, which is sufficient to hold 512 8KB blocks (my blocksize is 8KB). Then, I created a table such that a row fits on exactly one block—I'll never have two rows per block. Then, I fill this table up with 500 rows and COMMIT. I'll measure the amount of redo I have generated so far, run a SELECT that will visit each block, and then measure the amount of redo that SELECT generated.

Surprising to many people, the SELECT will have generated redo. Not only that, but it will also have "dirtied" these modified blocks, causing DBWR to write them again. This is due to the block cleanout. Next, I'll run the SELECT once again and see that no redo is generated. This is expected, as the blocks are all "clean" at this point.

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> create table t

2 ( x char(2000),

3 y char(2000),

4 z char(2000)

5 )

6 /

Table created.

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> set autotrace traceonly statistics

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> insert into t

2 select 'x', 'y', 'z'

3 from all_objects

4 where rownum <= 500;

500 rows created.

Statistics

----------------------------------------------------------

...

3297580 redo size

...

500 rows processed

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> commit;

Commit complete.

So, this is my table with one row per block (in my 8KB blocksize database). Now I will measure the amount of redo generated during the read of the data:

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> select *

2 from t;

500 rows selected.

Statistics

----------------------------------------------------------

...

36484 redo size

...

500 rows processed

So, this SELECT generated about 35KB of redo during its processing. This represents the block headers it modified during the full scan of T. DBWR will be writing these modified blocks back out to disk at some point in the future. Now, if I run the query again

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> select *

2 from t;

500 rows selected.

Statistics

----------------------------------------------------------

...

0 redo size

...

500 rows processed

ops$tkyte@ORA10G> set autotrace off

I see that no redo is generated—the blocks are all clean.

If we were to rerun the preceding example with the buffer cache set to hold at least 5,000 blocks, we'll find that we generate little to no redo on any of the SELECTs—we will not have to clean dirty blocks during either of our SELECT statements. This is because the 500 blocks we modified fit comfortably into 10 percent of our buffer cache, and we are the only users. There is no one else mucking around with the data, and no one else is causing our data to be flushed to disk or accessing those blocks. In a live system, it will be normal for at least some of the blocks to not be cleaned out sometimes.

This behavior will most affect you after a large INSERT (as just demonstrated), UPDATE, or DELETE—one that affects many blocks in the database (anything more than 10 percent of the size of the cache will definitely do it). You will notice that the first query to touch the block after this will generate a little redo and dirty the block, possibly causing it to be rewritten if DBWR had already flushed it or the instance had been shut down, clearing out the buffer cache altogether. There is not too much you can do about it. It is normal and to be expected. If Oracle did not do this deferred cleanout of a block, a COMMIT could take as long to process as the transaction itself. The COMMIT would have to revisit each and every block, possibly reading them in from disk again (they could have been flushed).

If you are not aware of block cleanouts and how they work, it will be one of those mysterious things that just seems to happen for no reason. For example, say you UPDATE a lot of data and COMMIT. Now you run a query against that data to verify the results. The query appears to generate tons of write I/O and redo. It seems impossible if you are unaware of block cleanouts; it was to me the first time I saw it. You go and get someone to observe this behavior with you, but it is not reproducible, as the blocks are now "clean" on the second query. You simply write it off as one of those database mysteries.

In an OLTP system, you will probably never see this happening, since those systems are characterized by small, short transactions that affect a few blocks. By design, all or most of the transactions are short and sweet. Modify a couple of blocks and they all get cleaned out. In a warehouse where you make massive UPDATEs to the data after a load, block cleanouts may be a factor in your design. Some operations will create data on "clean" blocks. For example, CREATE TABLE AS SELECT, direct path loaded data, and direct path inserted data will all create "clean" blocks. An UPDATE, normal INSERT, or DELETE may create blocks that need to be cleaned with the first read. This could really affect you if your processing consists of

- Bulk loading lots of new data into the data warehouse

- Running

UPDATEs on all of the data you just loaded (producing blocks that need to be cleaned out) - Letting people query the data

You will have to realize that the first query to touch the data will incur some additional processing if the block needs to be cleaned. Realizing this, you yourself should "touch" the data after the UPDATE. You just loaded or modified a ton of data; you need to analyze it at the very least. Perhaps you need to run some reports yourself to validate the load. This will clean the block out and make it so the next query doesn't have to do this. Better yet, since you just bulk loaded the data, you now need to refresh the statistics anyway. Running the DBMS_STATS utility to gather statistics may well clean out all of the blocks, as it just uses SQL to query the information and would naturally clean out the blocks as it goes along.

Log Contention