EVERY DAY, SOMEWHERE in the world a human being who is cast in the role of beneficiary of a trust accuses her or his trustee of being unresponsive to her or his request to be heard and to be represented. From this accusation (all too often true!) flow at least distress and disappointment and at worst litigation. How can a trust set up by one human being to benefit another come to such a tragic place? Easily, when we understand that the relationship between the trustee and the beneficiary is an arranged marriage.[33]

Since the beginning of the use of trusts in the Middle Ages, very few, if any, beneficiaries have chosen their trustees. Founders, grantors, settlors, whatever term we use (hereinafter I will use grantor), select the trustees of the trusts they create. Grantors of inter vivos revocable trusts (who are also the beneficiaries of such trusts) select the trustees for the new trusts that often grow out of their original trusts at their deaths. Grantors of all irrevocable trusts select the trustees of the trusts they create. Whether a trust becomes irrevocable by inter vivos deed or by death, it is the grantor who seeks, interviews, and selects the trustee. The beneficiary and the trustee, from the date of the trust's irrevocability forward, "for richer or for poorer, until death [or divorce, i.e. litigation] do them part," are irrevocably related.

Unfortunately for this relationship, arranged marriages have not been in vogue for some time. Even in the East they are beginning to be seen as an antique idea. Why? Because human beings believe that if they are going to give up any part of their freedom of action, it must be because the reward of doing so is perceived as being of greater value than the loss of freedom it requires. It is in the choosing that this balancing of risk and reward is carried out. It is the right to choose the party to the new relationship that makes the giving up of freedom possible. To be sure, the choice may be a poor one and the relationship may fail, but the responsibility for the outcome is accepted by the chooser. With choice comes responsibility for the relationship and for participating in it. In the beneficiary/trustee relationship, no reciprocal choice by the beneficiary takes place. The beneficiary is not invested with responsibility for the relationship or participation in it. The trustee does have some investment in the relationship, since the person named as trustee, whether individual or corporate, agreed to accept the role of trustee and the legal responsibilities associated with it.

Many trustees are not introduced to their new partner, the beneficiary, until the "wedding night" (following the signing of the trust agreement by the trust's grantor or on the grantor's death), and at this point a new relationship has to be formed. Unfortunately for most of these new beneficiary/trustee relationships, rarely do the parties understand that the human relationship they are entering will be far more important to the trust's success than the proper maintenance of their legal relationship. How quickly the trustee and beneficiary come to grips with this truth and begin to manage this human relationship will have a profound impact on how beneficial the trust will prove to be for both parties.

How can the beneficiary and trustee begin this relationship with the greatest possibility of success? Shortly, I will discuss some principles that excellent beneficiaries and excellent trustees must accept and fulfill for a successful relationship. For now, let me simply say that every individual or corporation considering accepting the role of trustee must comprehend and be willing to do three things:

1) understand that in agreeing to become a trustee, he or she is entering into a human relationship with the beneficiary, not just a legal one;

2) do everything in his or her power to get to know the potential beneficiary of the trust before the implementation of the trust; and

3) appreciate from the first meeting with the beneficiary that this relationship is an arranged marriage.

There is a second significant roadblock to a successful relationship between the trustee and the beneficiary. It is the failure of the grantor of the trust to perceive that in order for the recipient to have her or his life enhanced rather than depreciated by a gift, the recipient—the beneficiary of the trust—must believe that she or he is worthy of such a gift. We all know how disempowering gifts, or handouts, from the government have proven to be for the least privileged in our society. Why should we believe that the beneficiary of a trust is any different? In psychology, a new disease has been defined. It is called "remittance addiction." Every trust officer and every individual trustee lives with the knowledge that a poorly administered trust will result in this syndrome. What can be more disempowering to a human being than becoming dependent on, and waiting anxiously for, the check on the first of the month? Obviously, I am not speaking of people with physical or mental disabilities. I am speaking of trust beneficiaries who are perfectly able, physically and mentally, but who are as dependent on trust remittances as others are on drugs or alcohol.

Dependence creates all kinds of behavior; none are behavior choices free people make. Why do trusts carry this risk? First, many privileged families have been given no early warning messages by their trusted advisers that this problem exists. This is especially true in the families of first-generation entrepreneurs where there has been no historic experience with significant wealth or with trusts. Second, the largest number of trusts created each year are created for tax purposes. In my experience, most of these trusts are created without any careful thought being given to the beneficiary/trustee relationship and particularly to the issue of whether the beneficiary will consider herself or himself worthy of the gift. Tax planning is a necessity for families with wealth and must be carried out with excellence. However, over the time periods of one hundred years or more that are considered in this book, the tax planning of today will turn out to be barely relevant. A family's successful wealth preservation is in jeopardy if the family beneficiaries, the family's critical wealth, and its human capital are "remittance addicted" and are quickly taking the family out of business. A gift made principally for tax purposes has no life in it for the human beings who are supposed to be benefited. They will properly ask the trustee, "Why was I given this gift? Why am I worthy of it?" Only trouble will follow for a trustee who says "Because Grandpa loved you" when the trustee knows that Grandpa was actually more anxious to take something away from the tax collector than to give something to the beneficiary. The trustee's answer must be the truth, or the beneficiary will find the truth on his or her own and will never trust the trustee again. All too often the truth is that Grandpa wanted to take it with him, but since he could not and since the tax man was there, Grandpa decided to set up a monument to himself that would remind later generations of his family of his success as a wealth creator. In many instances, Grandpa really did not care about the impact of the gift on the beneficiary.

So here we have the trustee and the beneficiary in an arranged marriage where the beneficiary often will discover that the question of his or her personal worthiness to be in this relationship was never considered. Necessarily, this fact leaves the beneficiary in a quandary as to how to view the trust and his or her role in it. There are frequently many other unresolved issues of worthiness between the grantor and the beneficiary, too specific to each family fact pattern for me to discuss here. I will, however, quote my father, who taught me at the beginning of my legal career that "If at a grantor's death he or she has left unresolved issues in a relationship with the beneficiary of a trust, death in no way will resolve these issues but rather will leave the beneficiary behind to try to answer unanswerable questions." These questions will surface between the beneficiary and the trustee. How the trustee reacts to them will have a great deal to do with the success of the beneficiary/trustee relationship and whether the beneficiary feels worthy of the gift of the trust or falls into "remittance addiction."

I imagine many of you by now are disagreeing with me. You may be saying, "I know many grantors whose trusts were created as gifts of pure love and who had every intention that the beneficiary's life be improved and empowered by the gift." Happily, I too represent many such grantors. My larger experience, however, has taught me that they are not the grantors whose gifts lead to the need for this chapter. To the contrary, they and their families are the models who have taught me the lessons I am sharing with you about how to become an excellent beneficiary or an excellent trustee and how to forge an excellent beneficiary/trustee relationship.

I propose that the solution to a successful beneficiary/trustee relationship lies in the trustee's offering and the beneficiary's accepting the proposition that at the inception of the trust, the trustee's role is to be the beneficiary's mentor, and the trustee will remain in that role until the beneficiary is fully participating in the beneficiary/ trustee relationship, at which time the trustee's role will evolve into that of the beneficiary's representative. In all relationships that are successful learning experiences for both participants, the party with more knowledge at the beginning must offer that knowledge in such a way that the party with less knowledge willingly assumes the role of pupil. Then, as we saw in Chapter 17, when the student is ready, the teacher will know when to disappear.

In a beneficiary/trustee relationship, normally the trustee has the knowledge, both human and legal, of how the relationship is meant to work. The beneficiary normally does not. If the trustee at the outset of this relationship offers to mentor the beneficiary until he or she can achieve excellence, as discussed below, and if the beneficiary experiences the trustee's offer as true and as a gift, their relationship has an excellent chance of being successful.

Unfortunately, all too often, the trustee sees excellence as limited to investment and administrative success. The trustee fails to perceive that what he or she knows about the human and legal nature of the beneficiary/trustee relationship must be communicated to and learned and assimilated by the beneficiary if their relationship is to be a success. Even more unfortunate for a successful beneficiary/trustee relationship is the situation where the trustee wonders why this beneficiary who seems so intelligent in many areas of life seems so dense about a subject the trustee considers to be so simple. Why should this question even arise in a trustee's mind? All too often, in my experience, the trustee is a person or institution with excellent quantitative skills but little or no experience or training in qualitative issues. Meanwhile, the beneficiary is often a person with excellent qualitative skills who lacks experience in quantitative issues. Like the failures in communication between science and the humanities, it is not surprising that beneficiaries and trustees making fundamentally different journeys in life find it hard to understand one another.[34] If a trustee can recognize this mismatch and transcend it by offering to mentor the beneficiary so that she or he can learn and then exercise her or his role in the trust, their relationship stands a chance of harmony. Trustees who fail to learn at the outset of the trust what the beneficiaries do and don't understand about their relationship, or worse, assume the beneficiaries know all that's necessary "since, after all, this stuff is so simple anyone should understand it," do so at their peril.

To be asked to be a mentor is the highest honor that can be bestowed by one human on another. When selecting a trustee, the grantor of a trust is well advised to consider the potential trustee's ability to mentor the beneficiaries he or she loves as the highest qualification among all of the many things a trustee must do. If a trustee is an excellent administrator, a superb and prudent investor, and a Solomonic and humane distributor but is perceived by the beneficiary to be distant, aloof, and unable to communicate in a way the beneficiary can understand, their relationship will be unsuccessful. It is in the role of mentor that a trustee's real worth to the beneficiary, and thus to the grantor's desire to make a gift that is empowering to the beneficiary, can be found.

In my original proposition, I suggest that the trustee's relationship with the beneficiary must evolve from mentor to representative. The term representative suggests a form of governance. Trusts contain within their terms systems of governance. After all, whenever two or more persons are in any relationship, they must make joint decisions. Joint decision making means that the parties are in a system of governance. In the beneficiary/trustee system of governance, the trustee is the representative of the beneficiary, because it is to him or her that the trustee is accountable. If the trustee makes unilateral decisions and imposes them on a beneficiary who has no choice but to accept them, in political science terms we have a tyranny. When called to account, tyrants historically have not fared well. If the trustee makes joint decisions but always exercises the deciding vote, the beneficiary will quickly determine that there is no purpose in dealing with the trustee and opt out by silence or anger. If the trustee and the beneficiary make joint decisions, and the beneficiary has been mentored by the trustee and has become an equal party to the representative system of governance, the trustee will almost never have to exercise a deciding vote. The beneficiary will know that even if the trustee makes a decision with which he or she disagrees, the trustee is acting as his or her representative and the decision is likely to be a fair one.

It is my contention that the beneficiary/trustee system of governance works best when the trustee evolves from mentor to representative, and thus the system of governance becomes a republic— the same model I have proposed for governance within families. This system of beneficiary/trustee governance permits each party the greatest freedom, the greatest chance of mutual respect, and ultimately, the greatest trust. It would seem to me that every trustee, knowing that one day accounts must be rendered, will want the beneficiary judging these accounts to receive them in a spirit of mutual respect and trust. The alternative is the antithesis of trust and is symbolic of no "trust" ever having existed.

I believe that the beneficiary/trustee relationship, if it follows principles of joint learning based on mutual trust and respect, can be an extraordinarily successful one for both parties. It can offer to each a fulfilling role in long-term wealth preservation planning for the beneficiary.

However, unless the trustee accepts a role as the beneficiary's mentor and ultimate representative, the trust may never achieve the success the grantor hoped for when he or she created it as a gift of love and as a gift of hope for the enhancement of the beneficiary's individual pursuit of happiness.

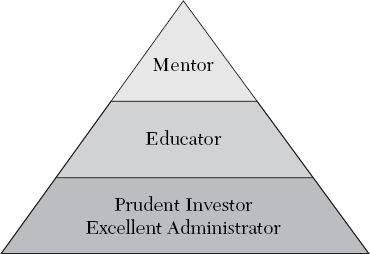

To help grantors and beneficiaries see clearly how to measure an excellent trustee, I close with a picture showing ascending levels of trustee excellence.

The first level represents an excellent quantitative trustee who fulfills all the legal requirements. The second level represents a trustee who in addition to excelling at the first level provides, when requested, the education the beneficiary seeks. The highest level, trustee as mentor, represents a trustee who proactively seeks out the beneficiary to provide both quantitative and qualitative excellence. As I have stated earlier, the title of mentor is the highest honor one human being can bestow on another. For a trustee to be so honored by a beneficiary is to achieve true excellence.

To each beneficiary and to each trustee who sets out on the journey to achieve excellence in this complex relationship, I salute your courage and trust that your journey together will be crowned with success.

[33] Portions of this chapter were originally published in slightly different form in The Chase Journal (Volume II, Issue 2, Spring 1998).

[34] For a helpful guide to the different ways we learn, refer to Daniel P. Goleman's book Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ (New York: Bantam Books, 1995).