Finding Your Logical Presentation Flow

Jerry Weissman

When you brainstorm potential ideas to include in your presentation and distilled those ideas into clusters, you used right-brain focus.

Next, you’re ready to shift to your left brain and put your clusters into a sequence, to develop a logical flow. It’s time to decide which cluster goes first, which goes in the middle, and which goes last. In other words, you need a clear path that links all of your clusters, a blueprint for determining the best order for the elements of your presentation. You need flow.

The best way to express the critical importance of flow to your audience is to start with the simple example of written text. One distinctive aspect of written text is that the reader, who is the audience to the writer, has random access to the writer’s content. If the reader, while browsing through a book, report, or magazine, encounters a word or reference that is unclear but looks familiar, the reader can simply place a finger in the current page and then riffle back through the prior pages to find the original definition or reference. The reader can navigate through the writer’s ideas independently.

Your presentation audience does not have that capability. They have only linear access to your content, one slide at a time. It’s like looking at a forest at the level of the trees, only one tree at a time.

You may be doing an excellent job of presenting one tree. Your audience may be suitably impressed, thinking, “That’s a superb tree: deep roots, thick bark, rich foliage!” But if, when you move on to the next tree, you don’t make it crystal clear how it relates to the first tree, your audience is forced to try to divine the relationship on their own. They no longer have access to the first tree, which forces them to work harder to remember it and draw the necessary connections.

At that point, your audience has three choices:

• They can fall prey to the MEGO (Mine Eyes Glaze Over) syndrome.

• They can interrupt you to ask for an explanation.

• They can start thinking in an effort to understand the missing link, and stop listening.

None of these options is acceptable. Don’t make them think!

Your job, therefore, is to become the navigator for your audience, to make the relationships among all the parts of your story clear for them. Make it easy for them to follow, to bring them up from the level of the trees and give them a view of the entire forest.

Doing this requires a road map, a plan, a formula. Like a chef who follows a recipe to use the right ingredients in the right order, you need to encompass all the Roman columns within an overarching template.

There are proven techniques for organizing ideas in a logical sequence to create a lucid and persuasive presentation. These techniques are called Flow Structures, and there are 16 different options for various types of presentations.

The 16 Flow Structures

1. Modular. A sequence of similar parts, units, or components in which the order of the units is interchangeable.

2. Chronological. Organizes clusters of ideas along a timeline, reflecting events in the order in which they occurred or might occur.

3. Physical. Organizes clusters of ideas according to their physical or geographic location.

4. Spatial. Organizes ideas conceptually, according to a physical metaphor or analogy, providing a spatial arrangement of your topics.

5. Problem/Solution. Organizes the presentation around a problem and the solution offered by you or your company.

6. Issues/Actions. Organizes the presentation around one or more issues and the actions you propose to address them.

7. Opportunity/Leverage. Organizes the presentation around a business opportunity and the leverage you or your company will implement to take advantage of it.

8. Form/Function. Organizes the presentation around a single central business concept, method, or technology, with multiple applications or functions emanating from that fundamental core.

9. Features/Benefits. Organizes the presentation around a series of your product or service features and the concrete benefits provided by those features.

10. Case Study. A narrative recounting of how you or your company solved a particular problem or met the needs of a particular client and, in the telling, covers all the aspects of your business and its environment.

11. Argument/Fallacy. Raises arguments against your own case and then rebuts them by pointing out the fallacies (or inaccuracies) that underlie them.

12. Compare/Contrast. Organizes the presentation around a series of comparisons that illustrate the differences between your company and other companies.

13. Matrix. Uses a two-by-two or larger diagram to organize a complex set of concepts into an easy-to-digest, easy-to-follow, and easy-to-remember form.

14. Parallel Tracks. Drills down into a series of related ideas, with an identical set of subsets for each idea.

15. Rhetorical Questions. Poses, and then answers, questions that are likely to be foremost in the minds of your audience.

16. Numerical. Enumerates a series of loosely connected ideas, facts, or arguments.

You can use these Flow Structures to group your clusters in a logical progression, making it easy for your audience to follow your presentation and easy for you to construct your presentation. To do that, let’s look more closely at each of the 16 Flow Structures, with brief examples of each. The chances are excellent that one or more of these Flow Structures can serve you well in organizing virtually any presentation.

Guidelines for Selecting a Flow Structure

When you are selecting a Flow Structure for your presentation, consider these factors:

• The presenter’s individual style. Choose a Flow Structure that feels right. A little experimentation and practice will help you decide which option works best for you. The fact that one of your colleagues had success with a particular Flow Structure doesn’t mean that you will, too. Of course, this mercifully puts to rest the very notion of the one-size-fits-all corporate pitch.

• The audience’s primary interest. As you’ve seen, different Flow Structures emphasize different aspects of the story. Choose a Flow Structure that focuses on the interests or concerns of your audience. Remember that Opportunity/Leverage works well for investor presentations and Form/Function for industry peer groups.

A biotechnology company used the Opportunity/Leverage Flow Structure for their IPO road show by starting with the opportunity (the market for their target disease) and then moving on to how their technology addressed or leveraged that market. Shortly after the company went public, they were invited to appear at an industry conference. For this presentation, they moved their Form (that is, their technology, or their secret sauce) to the top, and moved their Function (that is, the market for their technology) to the later position.

• Innate story factors. Some stories lend themselves naturally to a particular Flow Structure. Take advantage of that. For example, a company or industry going through a transition is a prime candidate for the Chronological option.

• The established agenda. If you are participating in a conference, seminar, or other gathering in which your presentation is expected to conform to a set format or respond to a particular challenge or question, use a Flow Structure that meets those requirements.

• Esthetic sense. Go with your instinct. If you have a strong sense that one Flow Structure just “looks good” or “sounds good” or “works well” when applied to your story, use it! Don’t try to cram your story into a Flow Structure that feels awkward. If you are comfortable making your presentation, you will transmit your comfort to your audience, and they will empathize with you.

As you can see, selecting a Flow Structure is more of an art than a science. You should also feel free to mix and match Flow Structures. It’s quite possible to combine two or three Flow Structures in a single presentation. Try different Flow Structures, but don’t limit yourself. Remember, it’s less important which Flow Structure you choose than that you make a choice.

The Value of Flow Structures

Dr. Emile Loria was the CEO of a French biotechnology company called BioVector Therapeutics, whose science was drug delivery through inhalants. Emile worked diligently with me, over many sessions, to develop the BioVector IPO road show. However, as often happens, the company was acquired instead of going public. Emile then became the CEO of an already-public U.S. biotechnology company called Epimmune, whose science was based on a naturally occurring substance called epitopes. Epimmune had harnessed epitopes to create vaccines to help the body’s immune system fight cancer and infectious diseases.

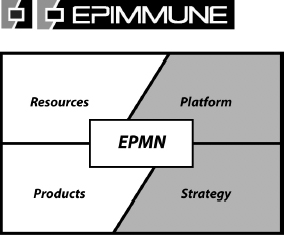

Emile called to ask me to review the Epimmune presentation that he was scheduled to deliver at a biotechnology conference. He emailed me a copy of his presentation. I downloaded it and looked at his overview slide, shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Epimmune overview slide

I called Emile and asked him which Flow Structure this represented. Although we had worked together many times, Emile hesitated. But then, after a moment, he said, “Aha! Form/Function!”

“Okay. Then why did you start with resources?” I asked.

After a moment, Emile exclaimed, “Of course! I should start with the Epimmune platform, our core science, our Form, and then move on to how it Functions with the products we derive from the platform, our strategy to develop the platform. And I should save the resources until the end to demonstrate how we will implement the strategy!”

“Aha!” I concurred.

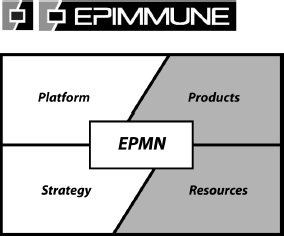

I spent less than two more minutes shuffling Emile’s slides into the correct order (see Figure 2), and then I tweaked a couple other slides (very little tweaking was needed for this diligent student). Then I emailed the presentation back to Emile.

It took less than five minutes for us to validate the clarity of Emile’s presentation. The forest view.

The Flow Structure approach provides an easy shorthand check of the logic and integrity of your ideas for both you and your audience. Your audience will be able to understand and follow any presentation. Even more important, they’ll readily remember your ideas.

Figure 2 Revised Epimmune overview slide.

The Four Critical Questions

So: Start with the Framework Form, do your Brainstorming and Clustering, and sequence them into a logical path with a specific Flow Structure.

All of these steps can be further distilled into the Four Critical Questions:

1. What is your Point B?

2. Who is your audience, and what is their WIIFY (What’s in it for Me)?

3. What are your clusters?

4. Why have you put the clusters in a particular order? In other words, which Flow Structure have you chosen?

Apply the same advice: Pose and answer each of these questions to every presentation you ever give from this moment on.

Your audiences will be grateful, and you will reap the rewards.